Abstract

Background

Overall response rate is frequently used as an endpoint in phase II trials of platinum-treated extensive stage small-cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC). We hypothesized that disease control rate (DCR) would be a superior surrogate for subsequent survival outcomes.

Methods

Updated patient-level data from SWOG trials in 2nd and/or 3rd line ES-SCLC patients were pooled. Landmark analysis was performed among patients alive at 8 weeks for overall survival (OS) measured from the 8-week landmark. Association of clinical prognostic factors with DCR was assessed using logistic regression. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess the associations between DCR at the landmark time and subsequent OS, adjusted for prognostic factors.

Results

Of the 319 ES-SCLC patients, 263 were alive at the 8-week landmark and constituted the pooled study population. Only eight patients had a response. Disease control at 8 weeks was seen in 98 patients. Bivariate analysis of OS from the 8-week landmark revealed that DCR (Hazard Ratio [HR] 0.47; p<0.0001), and elevated LDH (HR 1.70; p=0.0004),) were significantly associated with OS. In multivariable analysis, DCR remained an independent predictor of subsequent survival from the 8-week landmark (HR=0.50; p< 0.0001).

Conclusions

In this large 2nd- and 3rd-line ES-SCLC database, DCR at 8 weeks was found to be a significant predictor of subsequent survival in patients receiving investigational therapy. These results have critical implications in the selection of surrogate endpoints in future prospective ES-SCLC trials.

Background

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is a highly aggressive and virulent malignancy. Patients typically present with incurable systemic disease (i.e., “extensive stage”) at the time of initial diagnosis. The lethal phenotype of extensive stage SCLC (ES-SCLC) is perhaps best exemplified by its high rate of initial sensitivity to treatment with DNA damaging agents such as platinum-based chemotherapy; however, this is generally followed by the rapid development of drug resistance and subsequent disease progression.[1] Most recently, our group reported that platinum-sensitivity status may no longer be strongly associated with survival outcomes in ES-SCLC patients receiving investigational non-cytotoxic therapy in the salvage setting.[2,3] Ultimately, the result is that the estimated median survival time for patients with ES-SCLC is typically less than a year. The treatment approach to SCLC has not significantly advanced over the last quarter century, highlighting the importance of continued attention to the early development of novel agents for this aggressive disease.

The optimal metric to define the efficacy of an agent in phase II clinical trials of patients with previously-treated SCLC has not yet been clearly defined. The traditional measures of efficacy have included tumor response rate (now commonly assessed using RECIST) and progression-free survival (PFS). However, neither efficacy measure has yet been shown to be significantly associated with overall survival (OS) in this context. In the frontline setting, a pooled analysis of data from over 3000 patients enrolled in 12 trials failed to demonstrate surrogacy of PFS for OS in extensive stage SCLC, despite earlier work that suggested otherwise.[4,5]

In clinical practice, physicians and patients intuitively equate tumor response from systemic therapy with subsequent OS benefit. Similarly, investigators commonly use response rate as a metric for vetting new agents in the phase II context, advancing a “promising treatment” into further phases of drug development. However, several features of SCLC suggest that response rate may not be the ideal endpoint to predict survival outcomes. After front-line platinum-based chemotherapy, response to any subsequent agent tends to be extraordinarily transient and insufficiently durable to result in a survival benefit. Moreover, only a minority of patients with previously treated SCLC experience tumor shrinkage with any subsequent systemic therapy, including investigational agents. For example, in three SWOG phase II trials of investigational regimens in platinum-treated SCLC (S0802, S0435, and S0327; summarized in Table 1), responses were rare with many more patients having progression (PD) or stable disease (SD).[6–8]

Table 1.

Recent SWOG Trials in Previously Treated Extensive Stage SCLC

| SWOG Study | Regimen | Number of patients | Performance Status Allowed | Number of prior regimens allowed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S0327 | Bortezomib | 57 | 0–1 | ≥1 |

| S0435 | Sorafenib | 83 | 0–1 | ≥1* |

| S0802 | Topotecan +/− Aflibercept | 189 | 0–1 | 1 |

S0435 allowed patients with one or more prior chemotherapy regimens until February 1, 2006, when it was amended to allow only patients with exactly one prior regimen.

In 2008, our group reported that in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), disease control rate (DCR) – defined as the sum of partial (PR), complete response (CR) and SD – was the strongest predictor of subsequent survival following platinum-based chemotherapy.[9] In the present study, we hypothesized that DCR at 8-weeks would be a superior predictor of clinical benefit than tumor response rate in patients with ES-SCLC receiving investigational therapy in SWOG clinical trials.

Methods

Updated patient-level data from S0802, S0435, and S0327 were pooled. S0802 randomized patients to either topotecan alone or topotecan plus the angiogenesis inhibitor aflibercept (VEGF-Trap). S0435 was a single arm trial of the VEGFR-TKI sorafenib. S0327 was a single arm trial of the proteasome inhibitor PS-341 (bortezomib). The primary results for each of these trials have been published previously. Each of the trials required progression on at least one line of platinum-based chemotherapy, had consistent eligibility criteria, and collected the same baseline demographic variables. Disease assessments were performed every 6 weeks in S0802 and S0327, and every 8 weeks in S0435. Response was assessed using RECIST by the site investigators. While the primary endpoint was response rate for S0327 and S0435, the primary endpoint for S0802 was 3-month PFS and thus was the only one of the three trials that did not require measurable disease at baseline. Response was assessed in the subset of patients with measurable disease using RECIST and was defined as achieving a best response of either a confirmed or unconfirmed partial or complete response. Disease control was assessed in all patients and was defined as the absence of evidence of progression at the first follow-up disease assessment. Patients with no follow-up disease assessment due to symptomatic deterioration were included in the denominator as not having achieved disease control..

Because there were differences in cycle length and disease assessment times across the three protocols, we selected the longest of these (i.e., 8 weeks for S0435) as the landmark timepoint. Response and DCR at 8 weeks were evaluated as intermediate endpoints for OS using a landmark analysis among patients still alive at 8 weeks. In addition, response at 8 weeks was evaluated as an intermediate endpoint for PFS.

Overall survival and PFS estimates were calculated using the method of Kaplan-Meier. Confidence intervals for the median were constructed using the method of Brookmeyer Crowley. Overall survival was defined as the duration from the date of the 8 week landmark to the date of death due to any cause. Patients last known to be alive were censored at the date of last contact. Progression free survival was defined as the duration from the date of the 8 week landmark to the date of first documentation of disease progression, as defined by RECIST, symptomatic deterioration without documented disease progression, or death due to any cause. Patients last known to be alive and without evidence of disease progression or symptomatic deterioration were censored at the date of last contact.

Multivariate cox models were fit to evaluate the association of DCR and response with OS controlling for clinical prognostic factors (including age, sex, platinum sensitivity status, number of prior chemo, weight loss, and LDH, among others). Platinum sensitivity was defined as follows: platinum sensitive (progression ≥ 90 days from last platinum dose) or refractory (progression < 90 days). Missing values were not replaced or imputed in any way.

Prior to performing any data analysis, it was decided to adjust for multiple comparisons by only considering p-values ≤ 0.001 as statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS (SAS Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Of the 319 ES-SCLC patients, 263 were alive at the 8-week landmark and constituted the pooled study population. Patient characteristics were similar amongst the three trials and are summarized in Table 2. Overall, median age was 61 years. Males comprised 48% of the group while those with performance status 1 constituted 63%. There were 57 patients (22%) with clinically significant weight loss of >= 5% within the preceding 3 months. Elevated LDH was seen in 80 patients (30%).

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics, Patients Included in Landmark Analysis (N=263).

| S0327 (N=35) | S0435 (N=74) | S0802* (N=154) | Overall (N=263) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Age, median (range) | 65 | (22 – 85) | 62 | (44 – 85) | 63 | (40 – 85) | 63 | (22 – 85) |

| Age ≥ 65 | 17 | 49% | 30 | 41% | 60 | 39% | 107 | 41% |

| Male sex | 21 | 60% | 41 | 55% | 65 | 42% | 127 | 48% |

| Performance Status | ||||||||

| 0 | 12 | 34% | 29 | 39% | 55 | 36% | 96 | 37% |

| 1 | 23 | 66% | 43 | 58% | 99 | 64% | 165 | 63% |

| Not reported | 0 | 0% | 2 | 3% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 1% |

| Smoking Status | ||||||||

| Never | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 2% | 3 | 1% |

| Former | 0 | 0% | 37 | 50% | 96 | 62% | 133 | 51% |

| Current | 0 | 0% | 36 | 49% | 55 | 36% | 91 | 35% |

| Smoking status not reported | 35 | 100% | 1 | 1% | 0 | 0% | 36 | 14% |

| Weight Loss | ||||||||

| ≥ 5% | 6 | 17% | 15 | 20% | 36 | 23% | 57 | 22% |

| < 5% | 29 | 83% | 53 | 72% | 112 | 73% | 194 | 74% |

| Not reported | 0 | 0% | 6 | 8% | 6 | 4% | 12 | 5% |

| Elevated LDH | ||||||||

| Yes | 7 | 20% | 22 | 30% | 51 | 33% | 80 | 30% |

| No | 18 | 51% | 38 | 51% | 93 | 60% | 149 | 57% |

| Not reported | 10 | 29% | 14 | 19% | 10 | 6% | 34 | 13% |

| prior chemo regimens | ||||||||

| 2 or more | 18 | 51% | 6 | 8% | 0 | 0% | 24 | 9% |

| 0–1 | 16 | 46% | 67 | 91% | 154 | 100% | 237 | 90% |

| Not reported | 1 | 3% | 1 | 1% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 1% |

| Prior radiation therapy | 30 | 86% | 61 | 82% | 108 | 70% | 199 | 76% |

Overall, 263 patients were alive at the 8-week landmark and evaluable for the analysis of the association of disease control with overall survival. Comparing patients with disease control vs. no disease control, HR for OS was 0.42, with a statistically significant two-sided p-value of <0.0001. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Overall Survival (8-Week Landmark) Categorized According to Response or Disease Control

| Category | N* | Deaths | Median | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responders | 8 | 7 | 8.2 | 0.5 | 13.3 | 0.74 | 0.35 | 1.57 | 0.43 |

| Non-responders | 248 | 222 | 4.1 | 3.3 | 4.6 | ||||

| Disease Control | 98 | 79 | 8.6 | 6.1 | 10.5 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.62 | < 0.0001 |

| No Disease Control | 165 | 155 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 3.5 | ||||

Patients alive as of Week 8

Two-hundred fifty-six patients who had measurable disease at baseline were alive at 8 weeks and thus evaluable for OS from the 8-week landmark. There were 8 patients with a response. In the OS comparison of responders vs. non-responders, the hazard ratio (HR) was 0.74, with a two-sided p-value of 0.43.

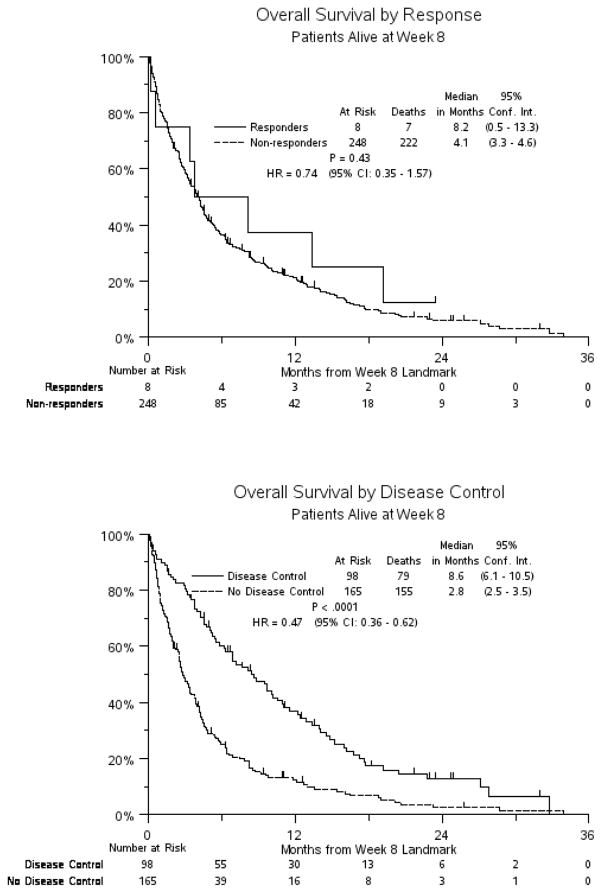

Kaplan Meier curves for OS from the 8-week landmark categorized according to response or disease control status are shown in Figure 1. Median OS (8-week landmark) was 8.2 months for responders vs. 4.1 months for non-responders (p=0.43), while median OS (8-week landmark) was 8.4 months for those with disease control vs. 3.1 months for those without disease control (p<0.0001).

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier Curves for Overall Survival According to Response or Disease Control

Bivariate analysis of baseline clinical and demographic variables and their association with subsequent OS is summarized in Table 4. As shown, DCR (HR 0.47, p<0.0001), and elevated LDH (HR 1.70, p=0.004) were significantly associated with subsequent OS.

Table 4.

Bivariate Analysis: Baseline Variables and Overall Survival from 8-week Landmark, patients with complete data at baseline (N=191)

| Parameter | HR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response | 0.74 | 0.35 | 1.57 | 0.43 |

| Disease control rate | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.62 | <.0001 |

| Platinum Refractory | 1.25 | 0.96 | 1.62 | 0.10 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 1.02 | 0.78 | 1.32 | 0.90 |

| Performance Status = 1 | 1.36 | 1.04 | 1.78 | 0.03 |

| Current Smoker vs. (Former or Never) | 1.05 | 0.79 | 1.40 | 0.75 |

| Male Sex | 1.12 | 0.86 | 1.45 | 0.40 |

| Elevated LDH | 1.70 | 1.27 | 2.28 | 0.0004 |

| 2 or more prior chemotherapy regimens vs. only 1 | 0.64 | 0.41 | 1.00 | 0.05 |

| Weight Loss ≥ 5% | 0.98 | 0.72 | 1.34 | 0.91 |

| Prior radiation therapy | 0.98 | 0.72 | 1.32 | 0.88 |

| S0802 vs. (S0435 or S0327) | 1.21 | 0.93 | 1.58 | 0.16 |

Multivariate analysis for OS accounting for all relevant baseline variables, including only those patients with complete data (N=191), showed that only DCR was independently associated with subsequent survival. (Table 5) All other variables, including baseline platinum-refractory status, performance status, and sex were not significantly associated with OS. Disease control rate at 8 weeks was an independent predictor of subsequent OS, with an estimated HR of 0.50 (95% CI 0.36, 0.70, p=0.0001), representing a 50% reduction in the risk of death.

Table 5.

Multivariate Analysis: Baseline Variables and Overall Survival from 8-week Landmark, patients with complete data at baseline (N=191)

| Parameter | HR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease control rate | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.70 | <.0001 |

| Platinum Refractory | 1.33 | 0.96 | 1.84 | 0.09 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 0.99 | 0.71 | 1.38 | 0.94 |

| Performance Status = 1 | 1.39 | 1.00 | 1.94 | 0.05 |

| Current Smoker vs. (Former or Never) | 1.00 | 0.71 | 1.40 | 0.98 |

| Male Sex | 1.16 | 0.83 | 1.61 | 0.38 |

| Elevated LDH | 1.38 | 0.98 | 1.94 | 0.06 |

| 2 or more prior chemotherapy regimens vs. only 1 | 0.58 | 0.29 | 1.17 | 0.13 |

| Weight Loss ≥ 5% | 1.11 | 0.75 | 1.63 | 0.61 |

| Prior radiation therapy | 0.78 | 0.54 | 1.13 | 0.18 |

| S0802 vs. (S0435 or S0327) | 1.03 | 0.71 | 1.50 | 0.88 |

In the subset of patients with measurable disease at baseline, 98 patients were alive and progression free at the 8-week landmark and therefore evaluable for assessment of PFS from the 8-week landmark. Of these, only 8 patients met PR criteria (9.1%). In the PFS comparison of responders vs. non-responders, the hazard ratio (HR) was 0.77 , with a two-sided p-value of 0.51. Kaplan Meier curves for PFS from the 8-week landmark categorized according to response status are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. Median PFS (8-week landmark) was 2.1 months for responders vs. 1.8 months for non-responders.

Discussion

In this modern SWOG database analysis of ES-SCLC patients receiving investigational therapy, DCR at 8 weeks was found to be the strongest independent predictor of subsequent OS. This finding parallels observations seen in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving platinum-based therapy and has critical implications for the design of future prospective trials in ES-SCLC.

An ideal surrogate end point ought to be strongly associated with OS. In addition, such an endpoint is expected to fully capture the net effect of a treatment on OS.[10] In the past, PFS had been proposed as a metric for phase II trials in ES-SCLC because of its reported surrogacy with OS.[5] Unfortunately, this surrogacy was not confirmed by a subsequent larger pooled analysis of cooperative group trials.[4] In the absence of an accessible database from a randomized trial that shows the OS benefit of a new agent over an existing control in this 2nd and/or 3rd line ES-SCLC setting, the landmark analysis presented herein provides a reasonable albeit less robust alternative to true surrogacy. Furthermore, in contrast to NSCLC, there is a paucity of highly active second-line treatments against SCLC; thus the lack of correlation between PFS and OS means that PFS may not be a good measure of clinical benefit with a new therapy in SCLC. [4] Finally, as the likelihood of a RECIST response is quite low in this pre-treated context (e.g., only eight patients had an objective tumor response in our database), DCR may be a more practical yardstick for efficacy screening as it is seen in more patients. Finally, our analysis suggests that DCR at 8 weeks is significantly associated with OS and therefore could be a more appropriate indicator of clinical benefit with a new therapy.

This pooled study is limited by its retrospective nature, the heterogeneity of investigational therapies employed in the individual trials, and the lack of molecular phenotype information that may influence prognosis independently. Our observation is certainly influenced by the much smaller proportion of patients who actually had tumor response to investigational therapy at 8 weeks (i.e., only 8 individuals out of the entire cohort). Given the size of this cohort, we have limited power to accurately assess the true survival of this group. This is in contrast to the much larger group of 98 patients who exhibit disease control at the 8-week time point. Thus, the rarity of tumor response to investigational agents in the phase II clinical trial contributes to its reduced ability to predict subsequent survival outcomes. However, consistent collection of relevant baseline variables and the relative homogeneity of protocol design inherent in SWOG trials greatly facilitate the reliability of the pooled analysis performed here.

If these results are validated in an independent dataset, they ought to be considered in future phase II clinical trials in ES-SCLC. For instance, the further development of a new anticancer agent that does not appreciably result in a RECIST response could be prematurely terminated even when substantial disease control is observed. Our current analysis suggests that in patient cohorts that have not been molecularly enriched, overall response may not be the ideal clinical trial metric to screen for disease activity given its rarity in that setting. Pending further confirmation, DCR at 8 weeks might be considered as a superior clinical trial metric to screen new agents in an “all-comers” population of ES-SCLC patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that DCR at 8 weeks was a strong predictor of subsequent survival in platinum pre-treated patients receiving investigational therapy for ES-SCLC. We propose that this metric be considered as a clinical trial endpoint to screen for drug activity of novel agents targeting this challenging disease. This metric has the potential to allow for a smaller sample size in a phase II trial than if OS were used as the primary endpoint, while still providing a meaningful measure of drug activity.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Practice Points.

-

What is already known about this subject?

The optimal intermediate endpoint that best predicts subsequent survival in

SCLC patients receiving investigational therapy has not yet been clearly defined.

Traditionally, response rate and progression-free survival endpoints have been employed to assess the efficacy of an investigational agent; however, these endpoints have not been shown to be associated with overall survival (OS) in SCLC.

Disease control rate (DCR) has not yet been formally assessed in this setting.

-

What are the new findings?

In a multivariate analysis for OS, DCR at 8 weeks was an independent predictor of subsequent OS, with an estimated HR of 0.50 (p<0.0001), representing a 50% reduction in the risk of death

-

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

If validated in an independent dataset, DCR ought to be considered as a clinical

trial endpoint to screen for drug activity of novel agents in relapsed SCLC

DCR has the potential to allow for a smaller sample size in a phase II trial than if OS were used as the primary endpoint, while still providing a meaningful measure of drug activity.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported in part by the following PHS Cooperative Agreement grant numbers awarded by the National Cancer Institute, DHHS: CA32102, CA38926, CA46441, and CA58882. Dr. Semrad is supported by the UC Davis Calabresi K12 Clinical Oncology Training Grant (CA138464, PI: Lara).

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 15th World Conference on Lung Cancer, October 2013, Sydney, Australia

Clinical Trials Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers NCT00068289, NCT00182689 and NCT00828139

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schneider BJ. Management of recurrent small cell lung cancer. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2008;6:323–31. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2008.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lara PN, Jr, Moon J, Redman MW, et al. Relevance of platinum-sensitivity status in relapsed/refractory extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer in the modern era: a patient-level analysis of southwest oncology group trials. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2015;10:110–5. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lara PN, Jr, Gandara DR, Redman MW. Reply to “diminishing role of platinum-sensitivity status in patients with small cell lung cancer”. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2015;10:e36. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster NRL, Schild S, Redman M, Wang X, Dahlberg S, Ding K, Bradbury P, Ramalingam S, Gandara D, Vokes, Adjei A, Mandrekar M. Multitrial evaluation of progression-free survival (PFS) as a surrogate endpoint for overall survival (OS) in previously untreated extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC): An Alliance-led analysis. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:7510. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foster NR, Qi Y, Shi Q, et al. Tumor response and progression-free survival as potential surrogate endpoints for overall survival in extensive stage small-cell lung cancer: findings on the basis of North Central Cancer Treatment Group trials. Cancer. 2011;117:1262–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lara PN, Jr, Chansky K, Davies AM, et al. Bortezomib (PS-341) in relapsed or refractory extensive stage small cell lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group phase II trial (S0327) Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2006;1:996–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gitlitz BJ, Moon J, Glisson BS, et al. Sorafenib in platinum-treated patients with extensive stage small cell lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG 0435) phase II trial. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2010;5:1835–40. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f0bd78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen JW, Moon J, Gadgeel SM, et al. SWOG 0802: A randomized phase II trial of weekly topotecan with and without AVE0005 (aflibercept) in patients with platinum-treated extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ESCLC) Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lara PN, Jr, Redman MW, Kelly K, et al. Disease control rate at 8 weeks predicts clinical benefit in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from Southwest Oncology Group randomized trials. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:463–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.0344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prentice RL. Surrogate endpoints in clinical trials: definition and operational criteria. Statistics in medicine. 1989;8:431–40. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.