Abstract

Tail regression is one of the most prominent transformations observed during anuran metamorphosis. A tadpole tail that is twice as long as the tadpole trunk nearly disappears within three days in Xenopus tropicalis. Several years ago, it was proposed that this phenomenon is driven by an immunological rejection of larval-skin-specific antigens, Ouro proteins. We generated ouro-knockout tadpoles using the TALEN method to reexamine this immunological rejection model. Both the ouro1- and ouro2-knockout tadpoles expressed a very low level of mRNA transcribed from a targeted ouro gene, an undetectable level of Ouro protein encoded by a target gene and a scarcely detectable level of the other Ouro protein from the untargeted ouro gene in tail skin. Furthermore, congenital athymic frogs were produced by Foxn1 gene modification. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that mutant frogs lacked splenic CD8+ T cells, which play a major role in cytotoxic reaction. Furthermore, T cell-dependent skin allograft rejection was dramatically impaired in mutant frogs. None of the knockout tadpoles showed any significant delay in the process of tail shortening during the climax of metamorphosis, which demonstrates that Ouro proteins are not essential to tail regression at least in Xenopus tropicalis and argues against the immunological rejection model.

Keywords: ouro, metamorphosis, tail regression, TALEN, genome editing, targeted gene knockout, Xenopus tropicalis

Introduction

Anuran metamorphosis has been a highly studied phenomenon for more than a century (Hertwig 1898). This process involves a systematic and physiological change from a larva to an adult, including the resorption of larval organs, development of adult organs, and remodeling of many organs and tissues. Tail regression is an especially conspicuous and dynamic change (Nakajima et al. 2005).

Thyroid hormone (TH) involvement in tadpole tail regression has been substantiated by the report that isolated tadpole tail tips shrink in the presence of thyroxine (Weber 1962). This TH-dependent tail resorption is also supported by the finding that metamorphic morphological changes, including the tail shortening program, are inhibited in transgenic Xenopus laevis (X. laevis) tadpoles overexpressing type III deiodinase, which degrades TH (Huang et al. 1999). A cultured myoblastic cell line derived from X. laevis tadpole tail died by apoptosis in response to TH (Yaoita & Nakajima 1997). In this process, a paracrine mechanism based on a TH-dependent soluble death-inducing factor is unlikely because cell death is not facilitated by adding the conditioned medium when cells were cultured with TH, suggesting a cell-autonomous manner, namely, the suicide model. This type of cell death of tail muscle in the presence of TH is observed during the climax of metamorphosis (stage 58–66), when many orchestrated changes appear simultaneously, and is almost completely inhibited by the overexpression of dominant-negative TH receptor (DNTR) (Das et al. 2002; Nakajima & Yaoita 2003).

Another mechanism that has been proposed suggests that programmed cell death is induced in a tail through the loss of a cell’s attachment to the extracellular matrix (ECM) due to the TH-dependent expression of ECM-degrading proteases such as collagenase-3 and stromelysin-3 (Brown et al. 1996) in the subepidermal fibroblasts surrounding the muscle cells, which is called the murder model (Berry et al. 1998). When a portion of the tail muscle cells are transfected with DNTR, non-transfected muscle cells that surround DNTR-expressing cells secrete ECM-degrading enzymes in response to TH to break down the ECM, and even DNTR-expressing cells are murdered (Fujimoto et al. 2007; Nakajima & Yaoita 2003). Cell death by murder starts at stage 62, when TH reaches a peak, and the expression of many types of ECM-degrading enzymes begin to show a prominent rise, especially MMP-9TH (Fujimoto et al. 2006).

The immunological rejection of a tail has been proposed as a third model. This idea originally comes from the findings that young frogs reject skin grafts from syngenic tadpole tails and that the secondary response of rejection is accelerated (Izutsu & Yoshizato 1993). This model is becoming generally accepted because precocious tail degeneration is promoted by the overexpression of ouro1 and ouro2, which encode keratin-related proteins and are specifically expressed in larval skin, and because the knockdown of one ouro gene slows down the tail regression process and results in tailed frogs (Mukaigasa et al. 2009).

In the immunological rejection model, a tailed frog is produced by the knockdown of ouro gene expression (Mukaigasa et al. 2009). As TH treatment represses Ouro protein expression in the tail (Watanabe et al. 2003), it should impair the immunological rejection of Ouro proteins. In contrast, tailed frogs are also generated by reducing TH signaling during the climax through methimazole treatment of stage 57/58 tadpoles to inhibit TH synthesis (Elinson et al. 1999) or through overexpression of type III deiodinase to inactivate TH (Huang et al. 1999).

In this study, we reexamine the immunological rejection model. Using targeted gene disruption, which has become a common and facile method, ouro1- and ouro2-knockout tadpoles were generated using the TALEN method, and congenital athymic tadpoles were created by modifying the Foxn1 gene to delete T cells. Tail regression was examined and compared with wild-type tadpoles.

Results

Developmental expression of ouro1 and ouro2 mRNA and proteins during Xenopus tropicalis (X. tropicalis) metamorphosis

We searched the X. tropicalis genome and cDNA database for ouro1 and ouro2 genes using the nucleotide and amino acid sequences of X. laevis ouro genes. Only one gene locus was found for ouro1 and ouro2 orthologs, respectively. The sequence comparison between X. laevis and X. tropicalis revealed 88.3% and 92.2% identities for ouro1 and ouro2 genes, respectively, at the nucleotide level in the coding region and 90.2% and 90.7% identities for Ouro1 and Ouro2 proteins, respectively, at the amino acid level (Figs. S1,S2 in Supporting information). ouro1 and ouro2 mRNA are reportedly expressed in X. laevis tail skin from stage 50 to 62 (Mukaigasa et al. 2009). Our quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assay showed that both ouro mRNAs were observed in X. tropicalis tail skin until stage 60 but not at stage 63 (Fig. 1A,B). Skinned tail expressed less than 1/1500 of ouro1 mRNA and 1/500 of ouro2 mRNA compared to tail skin at stages 56, 58 and 60, which indicated the skin-specific expression of ouro mRNA in the tail.

Fig. 1.

Developmental expression of ouro1 and ouro2 mRNA and proteins during X. tropicalis metamorphosis. (A, B) The expression levels of ouro1 mRNA (A) and ouro2 mRNA (B) in tail skin (solid line) and skinned tail (dotted line) from stage 56 to 63. Data are expressed as the means ± s.e.m. (N = 3 to 6). (C, D) Western blots showing the expression levels of Ouro1 protein (C) and Ouro2 protein (D) in back and tail skin from stage 56 to 64.

Ouro proteins are known to be present in X. laevis tail skin at stages 54–64 but absent in trunk skin at stage 62. Western blot analysis revealed that the expression of Ouro proteins persisted until stage 64 in X. tropicalis tail skin, but Ouro1 protein was undetectable at stage 62 and Ouro2 was hardly observed in the back skin (Fig. 1C,D). Taken together, these results indicated that the spatio-temporal expression patterns of ouro mRNA and proteins in X. tropicalis are similar to those in X. laevis.

Generation and analysis of ouro1-knockout tadpoles

Ouro protein contains a central rod domain flanked by N- and C-terminal glycine-serine rich domains. We designed anti-ouro1 TALEN target sites in the first exon (Fig. 2A). The sites are located at the protein level in the N-terminal glycine-serine rich domain and upstream of the region that was to have T-cell proliferation activity in X. laevis (Mukaigasa et al. 2009) (Fig. S2A in Supporting information). The 100 kb region encompassing the ouro2 genomic gene was searched for anti-ouro1 TALEN target sites using the left and right recognition sequences 5’-CRRTRCTRRRRCTRRTCC-3’ and 5’-RCTTRRCCCRRRRCCR-3’ (where R is A or G), respectively, because a TALEN DNA binding repeat that recognizes the nucleotide G also binds to the nucleotide A. There were no sequences with eight or fewer mismatched nucleotides and 10 to 30 spacer nucleotides.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of the ouro1-knockout tadpole. (A) The target sites (arrowheads) of anti-ouro1 TALEN in ouro1 genomic gene and Ouro1 protein. The black boxes and the arrow indicate exons and the transcriptional direction, respectively. (B) Expression levels of ouro1 and ouro2 mRNA in the tail skin of stage 60 wild-type and ouro1-knockout tadpoles. Levels of ouro1 mRNA were determined using a pair of primers downstream and another pair of primers (5’) upstream of the TALEN target sites. Data from wild-type tadpoles are expressed as the means ± s.e.m. (N = 6). (C, D) Expression levels of Ouro1 (C) and Ouro2 (D) proteins in the tail and back skin of stage 60 wild-type and ouro1-knockout tadpoles.

Pooled genomic DNA was extracted from ten F0 embryos three days after fertilization and TALEN mRNA injection to determine the ouro1 mutation rate. All examined genes were modified (14/14) and contained in-frame (9/14) or out-of-frame mutations (5/14) (Fig. S3A). F0 embryos underwent normal metamorphosis and developed into sexually mature adult frogs. Four male and five female F0 frogs were mated to obtain offspring. The genotypes of 58 F1 frogs were determined and showed in-frame (75/116) and out-of-frame (32/116) mutations as well as a large deletion of 715 base pairs (bp) containing the initiation codon (9/116) (Table 1). The lower frequency of out-of-frame mutations suggests that the out-of-frame mutations compromise the F1 survival rate, which may make it difficult to obtain ouro1-knockout frogs.

Table 1.

Genotype analysis of F1 tadpoles

| wt/wt | wt/in | wt/out | genotype in/in |

in/out | out/out | in/Ldel | out/Ldel | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ouro1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 20 | 5 | 7 | 2 |

| (0.0%) | (0.0%) | (0.0%) | (43.6%) | (36.4%) | (9.1%) | (12.7%) | (3.6%) | |

| ouro2 | 2 | 3 | 25 | 0 | 6 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| (4.3%) | (6.4%) | (53.2%) | (0.0%) | (12.8%) | (23.4%) | (0.0%) | (0.0%) | |

| Foxn1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| (0.0%) | (0.0%) | (3.7%) | (7.4%) | (37.0%) | (51.9%) | (0.0%) | (0.0%) | |

Only athymic tadpoles were selected in F1 offspring obtained by mating F0 frogs that had been injected with anti-Foxn1 TALEN mRNA. wt, wild-type target sequence; in, in-frame mutation; out, out-of-frame mutation; Ldel, a large deletion of 715 bp containing the initiation codon.

RNA and tissue lysates were prepared from the skin of stage 60 tadpole, with a deletion of 4 bp and an insertion of 15 bp in the ouro1 coding region of one chromosome and a deletion of 715 bp on the other chromosome (Fig. S3B in Supporting information), and subjected to qPCR and Western blot analyses, respectively. The level of ouro1 mRNA decreased to 1/26 and 1/50 in the ouro1-knockout tadpole tail compared with the stage 60 wild-type tadpole tails when qPCR was conducted using one pair of primers downstream and another pair upstream of the TALEN target sites, respectively (Fig. 2B). The nonsense-mediated RNA decay (NMD) pathway may degrade mRNA transcribed from one ouro1 gene with the out-of-frame mutation, and the low promoter activity may reduce transcription from the gene on the other chromosome, where the deleted region extends from more than 300 bp upstream of the initiation codon to approximately 400 bp downstream into the coding region. The expression level of ouro2 mRNA was not affected in the knockout tail skin.

The protein analysis revealed that Ouro1 protein was absent in the tail and back skin of the stage 60 ouro1-knockout tadpole, and Ouro2 protein was also scarcely detected in the tail skin (Fig. 2C,D). The hagfish counterparts of Ouro proteins, thread keratin α and γ, form a stable complex in vitro (Schaffeld & Schultess 2006). It is possible that the Ouro2 protein was destroyed by the protein quality control mechanism because it may fail to fold correctly due to the absence of its normal partner protein Ouro1. The results showed that both the out-of-frame mutation and a large deletion of the ouro1 gene prevented the translation of intact Ouro1 protein and reduced the expression level of Ouro2 protein.

Prominent tail regression is observed between stages 62 and 65 in wild-type tadpoles, when the tail is reduced in three days from 30 mm long to 1 mm long (Fig. 5A). Tadpoles are staged from stage 63 to 65 based on the ratio of tail length to body length. We examined five tadpoles with biallelically different out-of-frame mutations (out/out) or an out-of-frame mutation and a large deletion (out/Ldel) (Fig. S3B in Supporting information). There was no significant difference in the time required for the tail shortening from stage 62 to 65 between wild-type and ouro1-knockout tadpoles (Fig. 5B), and only no-tailed frogs were obtained (Fig. S4 in Supporting information), indicating that neither the Ouro1 nor the Ouro2 protein is necessary for tadpole tail regression.

Fig. 5.

Tails regressed in ouro1-, ouro2-, and Foxn1-knockout tadpoles similarly to wild-type tadpoles. (A) Photographs of wild-type stage 62 and 65 tadpoles. Scale bars = 5 mm. (B) The time required for wild-type tadpoles and ouro1-, ouro2-, and Foxn1-knockout tadpoles to develop from stage 62 to 65. Data are expressed as the means ± s.e.m. wt, wild-type; in, in-frame mutation; out, out-of-frame mutation; Ldel, a large deletion.

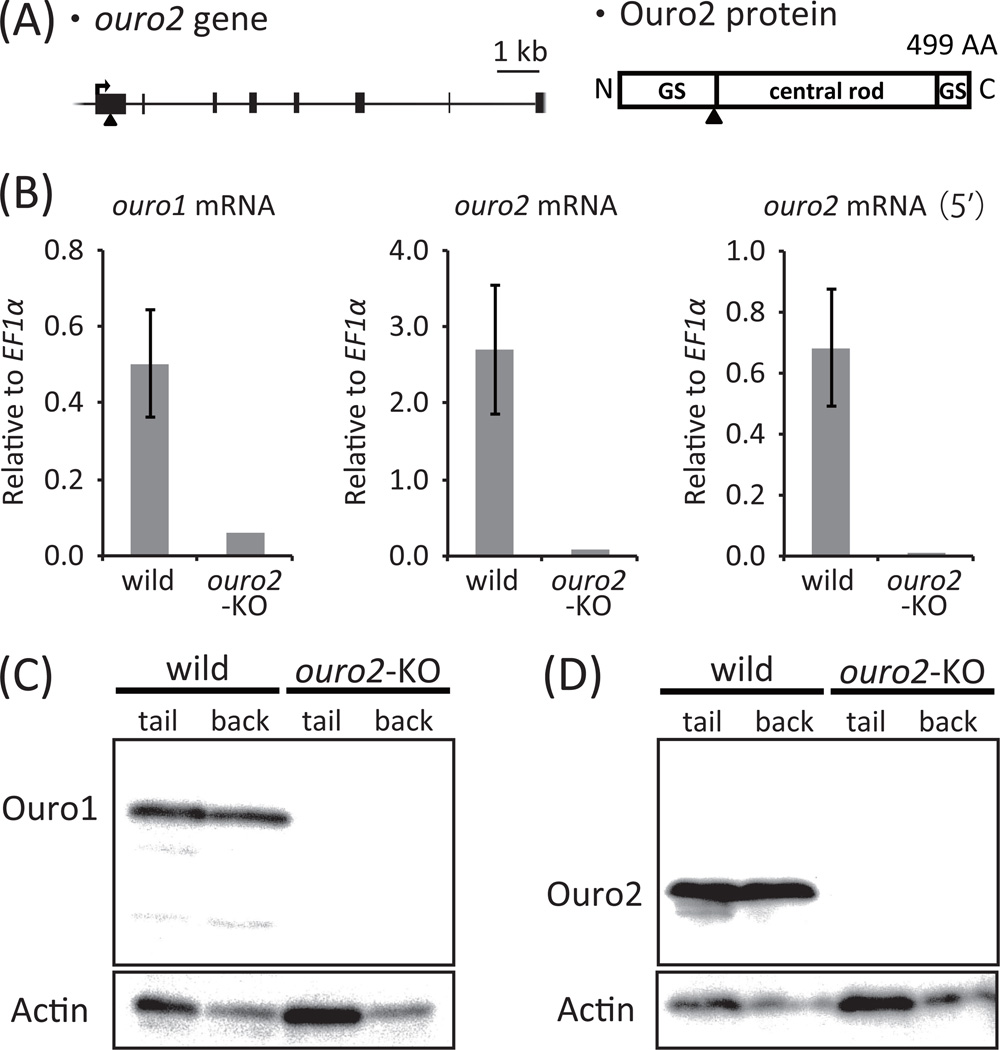

Generation and analysis of ouro2-knockout tadpoles

An anti-ouro2 TALEN was designed to target the first exon (Fig. 3A). The target sites are located at the juncture between the N-terminal glycine-serine rich and the central rod domains and in the region that is expected from the analysis of X. laevis (Mukaigasa et al. 2009) to have T cell proliferation activity (Fig. S2B in Supporting information). No sequences similar to the anti-ouro2 TALEN target sites were found with eight or fewer mismatched nucleotides and 10 to 30 spacer nucleotides within 340 kb of the genomic DNA region containing the ouro1 gene.

Fig. 3.

Characterization of the ouro2-knockout tadpole. (A) The target sites of anti-ouro2 TALEN in ouro2 genomic gene and Ouro2 protein. The alignment is labeled as described in the legend to Fig. 2. (B) Expression levels of ouro1 and ouro2 mRNA in tail skin of stage 60 wild-type and ouro2-knockout tadpoles. Levels of ouro2 mRNA were determined using a pair of primers downstream and another pair of primers (5’) upstream of the TALEN target sites. Data from wild-type tadpoles are expressed as the means ± s.e.m. (N = 6). (C, D) Expression levels of Ouro1 (C) and Ouro2 (D) proteins in the tail and back skin of stage 60 wild-type and ouro2-knockout tadpoles.

Wild-type ouro2 sequences (2/26), in-frame mutations (13/26) and out-of-frame mutations (11/26) were observed by analyzing pooled genomic DNA derived from ten three-day-old F0 tadpoles that had been injected with anti-ouro2 TALEN mRNA (Fig. S5A in Supporting information). The mating of six male and two female F0 frogs generated 47 offspring that harbored wild-type ouro2 sequences (32/94), in-frame mutations (9/94), and out-of-frame mutations (53/94) (Table 1). RNA and tissue lysates were prepared from the skin of the stage 60 tadpole, with a deletion of 2 bp in the ouro2 gene on one chromosome and a deletion of 8 bp on the other chromosome (Fig. S5B in Supporting information), and subjected to RNA and protein analyses, respectively. qPCR analysis showed the reduction of ouro2 mRNA to 1/32 and 1/64, using a pair of primers downstream and another pair upstream of the target sites, respectively, in the tail skin of the ouro2-knockout tadpole compared with wild-type tadpoles (Fig. 3B). A low level of ouro2 mRNA may be ascribed to the NMD pathway. In Western blot analysis, Ouro2 protein was undetectable in the tail and back skin of the ouro2-knockout tadpole and Ouro1 protein was hardly observed (Fig. 3C,D). The latter can be explained by the protein quality control mechanism described above and by the reduced level of ouro1 mRNA due to unknown reasons. Our results demonstrated that Ouro1 protein expression was very low, and intact Ouro2 protein was not detected in the ouro2-knockout tadpole tail and back skin.

All the examined ouro2-knockout tadpoles exhibited shortened tails during the metamorphosis climax without any significant delay, similar to the wild-type and wt/out mutant (Fig. 5), and did not retain any tail after the completion of metamorphosis (Fig. S4 in Supporting information), demonstrating that neither the Ouro1 nor the Ouro2 protein is required for tadpole tail regression.

Generation and analysis of Foxn1-knockout tadpoles

Anti-Foxn1 TALEN was constructed to examine whether the immunological rejection by T cells and more particularly CD8 cytotoxic T cells plays a pivotal role in tadpole tail regression. The mutation of Foxn1 should lead to a phenotype similar to that of a nude mouse, which shows a congenital loss of the thymus and mature T cells, including helper and cytotoxic T cells and, therefore, the defect of immunological rejection by CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (Nehls et al. 1994). Anti-Foxn1 TALEN target sites were designed in the seventh exon. At the protein level, the sites are located in the DNA-binding domain and upstream of the transcriptional activation domain (Fig. 4A). The Foxn1 gene was analyzed using pooled genomic DNA derived from ten three-day-old F0 tadpoles. All genes were modified and harbored in-frame (2/12) or out-of-frame (10/12) mutations (Fig. S6A in Supporting information). The thymus is easy to observe in the head region of living tadpoles after stage 52 (Fig. 4B). We chose three male and three female F0 frogs that had no thymus and mated them. Only athymic F1 tadpoles were selected and subjected to genotype analysis. Fourteen of 27 tadpoles contained biallelically different out-of-frame mutations (Fig. S6B in Supporting information). As the tadpoles with wt/out, in/in, and in/out mutations had no thymus, some out-of-frame and in-frame of mutations might interfere with gene function as a dominant-negative inhibitor (Table1).

Fig. 4.

Characterization of the Foxn1-knockout tadpoles. (A) The target sites of anti-Foxn1 TALEN in Foxn1 genomic gene and Foxn1 protein. The alignment is labeled as described in the legend to Fig. 2. (B) Photographs of heads of stage 56 wild-type and Foxn1-knockout tadpoles. Arrowheads indicate the thymus in the wild-type tadpole. There is no thymus in the Foxn1-knockout tadpole. Scale bars = 3 mm. (C) Flow cytofluorometric analysis of splenocytes from wild-type and Foxn1-knockout frogs after staining with mouse anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody (AM22 or F17) and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgM antibody. (D) Transplantation of ventral skin grafts from wild-type Nigerian H (NH) and Ivory Coast (IC) strains to the backs of IC wild-type and Foxn1-knockout frogs. Note that both grafts survived on the back of Foxn1-knockout frog for more than one hundred days. Scale bars = 1 mm.

Fluorescein-activated cell sorter analysis using monoclonal antibodies against Xenopus CD8, AM22 and F17 revealed a loss of CD8+ cells in the spleen of a frog (#13) with biallelically different out-of-frame mutations (Fig. S6B in Supporting information), whereas there were CD8− and CD8+ peaks in the splenic cells of wild-type frogs (Fig. 4C). Foxn1-knockout tadpoles underwent metamorphosis normally and proceeded from stage 62 to 65 in approximately three days without any delay compared to wild-type tadpoles (Fig. 5) and did not have a tail after the completion of metamorphosis (Fig. S4 in Supporting information).

To confirm the impaired immunological rejection in Foxn1-knockout frogs, we examined the ability to reject a transplanted skin graft from a different strain. The Ivory Coast frog strain rejects transplanted skin grafts from the Nigerian H (Yasuda) strain (Kashiwagi et al. 2010). White ventral skin grafts of Ivory Coast and Nigerian H strains were transplanted to the backs of wild-type and Foxn1-knockout Ivory Coast frogs. Ivory Coast recipients acutely rejected skin grafts from Nigerian H donors within 13.1 days ± 1 at 26°C (n = 5), indicating a major histocompatibility (MHC)-disparate rejection, whereas slower chronic rejection (68.6 days ± 7.7; n = 5) occurred when skin grafts from Ivory Coast donors were transplanted onto Ivory Coast recipients, which implies minor histocompatibility-disparate rejection. In sharp contrast, neither MHC-mismatched Nigerian H nor minor histocompatibility-mismatched Ivory Coast skin transplants were rejected by Foxn1-knockout #2 and #3, which survived for as long as 105 days at 26°C (Fig. 4D and Fig. S7 in Supporting information). Foxn1-knockout #2 and #3 harbored the biallelically different out-of-frame mutations (Fig. S6B in Supporting information), and developed from stage 62 to 65 in three days. Three other knockout recipients were fully tolerant to skin transplants from Nigerian H donors but showed ambiguous reaction to skin transplants from Ivory Coast donors characterized by inflammation with heavy vascularization in the grafted tissue at early time points and different degree of melanophore infiltration. Such allogeneic responses may be mediated by NK cells or other innate immune cell effectors as reported for T cell deficient mouse (Kroemer et al. 2008; Zecher et al. 2009).

Discussion

Ouro proteins are not necessary for tail regression in X. tropicalis

Our ouro1- and ouro2-knockout tadpoles showed no delay in tail regression during the climax and did not retain a tail after the completion of metamorphosis, which clearly demonstrated that neither the ouro1 nor ouro2 gene is necessary for tail regression.

The ouro2 gene should not be modified in ouro1-knockout tadpoles, as we could not find any sequence with eight or fewer mismatched nucleotides in the 100 kb region containing the ouro2 gene, compared with the target sites (18 bp and 16 bp) of the anti-ouro1 TALEN. Therefore, anti-Ouro2 antibody can recognize all expressed Ouro2 protein, and the protein analysis showed a very low expression level of Ouro2 in the ouro1-knockout tadpole tail. However, we cannot exclude the possibility of the expression of a truncated N-terminal Ouro1 protein because our anti-Ouro1 antibody was prepared by immunizing a synthetic peptide located downstream of the anti-ouro1 TALEN target sites. When an out-of-frame mutation was introduced by TALEN, it may have resulted in the premature termination and synthesis of the truncated N-terminal protein that contains only the glycine-serine rich domain but not the central rod domain with adult T cell proliferation activity (Mukaigasa et al. 2009). Our finding that an upstream part of ouro1 mRNA also decreased to 1/50 corroborated that the truncated Ouro1 protein was expressed at a very low level, if it was produced at all. The same argument applies to the ouro2-knockout frogs.

Our conclusion is inconsistent with a previous report that the knockdown of ouro expression by heat-inducible antisense ouro RNA delayed tail shortening and generated tailed frogs using X. laevis transgenic tadpoles (Mukaigasa et al. 2009). The authors of that report presented the results of ouro mRNA and protein analyses using a heat-shocked tail, but the RT-PCR result was not quantitative, and many Ouro2 signals were still observed in the immunostaining of the tail tip of the ouro2-knockdown tadpole. In spite of the low efficiency of the ouro2 knockdown, tail shortening was delayed significantly after the heat shock of the stage 58/59 transgenic tadpoles. In our study, the targeted ouro genes were modified or deleted to extinguish the gene function, the expression levels of the mRNA were reduced to 1/26–1/64, and the translated proteins of targeted and non-targeted ouro genes were expressed at undetectable and very low levels, respectively. In these conditions, a delay of tail regression and retained tails were not observed. It is possible that the active apoptotic pathway in the regressing tail was hindered by the harmful effect of heat shock in the previous authors' experiments. Our results clearly demonstrated that Ouro proteins are not essential to tail regression. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that this discrepancy is ascribed to the difference between X. tropicalis and X. laevis, that unknown molecules other than Ouro proteins act as larval antigens for the immunological rejection in our knockout tadpoles, or that antisense ouro RNA not only inhibits ouro gene expression but also incidentally influences the expression of genes that are important to tail regression.

The mechanism of tadpole tail regression

Tail muscle cell death is detected and the tip of the tail begins to atrophy at stage 58 (Nakajima & Yaoita 2003; Nieuwkoop & Faber 1956; Nishikawa & Hayashi 1995), which indicates that tail degeneration starts at the beginning of the metamorphosis climax, that is, before the immunological rejection system is established. Only cell-autonomous death (suicide) by TH signaling could be responsible for the early change.

Tail fins are reduced considerably and the notochord begins to degenerate posteriorly at stage 61 (Nieuwkoop & Faber 1956). ECM-degrading enzymes are expressed abruptly in the tail starting at stage 62 (Fujimoto et al. 2007). Tail shortening also starts at stage 62. It is possible that all the mechanisms based on the suicide, murder, and immunological rejection models collaborate to eliminate a tail during the latter half of the metamorphosis climax. However, our results argue against the immunological rejection model.

In the immunological rejection model, it is not known which immune cells kill tail cells. CD8+ cells were not required in normal tail regression during the metamorphosis climax in the congenital athymic Foxn1-knockout tadpoles with undetectable levels of CD8+ cells in the spleen. This finding excludes the possibility that cytotoxic immune cells such as conventional MHC class Ia-restricted CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CTLs), classical class Ia-unrestricted CTLs, and natural killer T cells play a pivotal role in tail rejection because these cells are all CD8-positive (Edholm et al. 2014). Natural killer cells fail to kill class Ia-deficient tumor cells before and after metamorphosis, suggesting that they have no cytotoxic activity during metamorphosis (Horton et al. 2003). Recently, nonclassical MHC class I-dependent invariant T cells (iT cells) have been reported to show in vivo cytotoxicity in tadpoles against tumor cells that are deficient in both class Ia and class Ib XNC10 (Edholm et al. 2013). iT cells are classified into type I and type II. Type I iT cells are CD8/CD4 double negative, and type II cells have a lower level of CD8 expression compared with conventional T cells. Type I iT cells may be good candidates for eliminating the tail, although they develop in the thymus.

The congenital loss of thymus by the modification of Foxn1 gene should result in the absence of all T cells containing not only CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, but also CD4+ helper T cells and iT cells. This should also lead to the compromised cytokine-mediated cell-cell interaction and the failure of adaptive immunity in knockout animals. The normal tail regression in Foxn1-knockout tadpoles strongly suggest that adaptive immunity is not involved in the tail elimination.

While the impairment of skin allograft rejection provides a strong evidence of the T cell deficiency of Foxn1-knockout frogs, the occurrence of unconventional inflammation-associated rejection patterns by some Foxn1-knockout recipients for skin of one of the two donor genotypes (Ivory Coast) suggests an alloreaction by innate immune cell effectors such as NK cells and/or monocytes. As such, we cannot exclude the possibility that some of these innate immune effector cells are involved in the elimination of the tail during metamorphic climax. However, wild-type X. tropicalis tadpoles proceed from stage 60 to 65 in nine days in our laboratory without obvious inflammation, heavy vascularization, and bleeding in the tail. Moreover, our study clearly demonstrates that larval-skin-specific Ouro proteins are not essential to tail regression. Thus, we believe that it is important to reexamine the immunological rejection model that is based on the observation that tadpole skin grafts are rejected by isogenic frogs.

Experimental Procedures

Animals

The Ivory Coast and Nigerian H (Yasuda) lines of X. tropicalis were provided by the Institute for Amphibian Biology (Graduate School of Science, Hiroshima University) through the National Bio-Resource Project of the MEXT, Japan. Tadpoles were staged according to the Nieukoop and Faber method (Nieuwkoop & Faber 1956). Tadpoles and frogs were maintained at 26–28°C and 24°C, respectively. All of the animals were maintained and used in accordance with the guidelines established by Hiroshima University for the care and use of experimental animals.

qPCR

Total RNA was purified from tadpole skin and skinned tails using the SV Total RNA Isolation System kit (Promega), which includes a DNase I treatment step. Samples of 1 µg of total RNA were denatured at 65°C for 5 min, reverse transcribed with 9-mer random and oligo-dT primers using the ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix (TOYOBO) at 37°C for 15 min, and inactivated at 50°C for 5 min and 98°C for 5 min. Diluted products (2 µl) were subjected to qPCR using a SYBR Premix Ex Taq II kit (TaKaRa) in 20 µl of reaction solution. qPCR was performed using a Thermal Cycler Dice Real-Time System (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The reaction conditions included pre-denaturation (95°C, 30 s) and a two-step protocol {(95°C, 5 s; 60°C, 30 s)×40}. The results were analyzed using a Thermal Cycler Dice Real-Time System Ver. 4.00 (TaKaRa). The level of specific mRNA was quantified and normalized to the level of elongation factor 1-α mRNA. The primer sequences used for the amplifications are shown in Table S1 in Supporting information.

Construction of the TALENs

TALEN repeats were assembled as previously described (Cermak et al. 2011), with minor modifications (Nakajima et al. 2013), and were inserted into pTALEN-ELD and pTALEN-KKR (Lei et al. 2012; Nakajima & Yaoita 2013) to generate anti-ouro1, anti-ouro2, and anti-Foxn1 TALEN expression constructs. The target sequences of TALEN are shown in Figs. S1, S3, S5, and S6 in Supporting information.

RNA microinjection into fertilized eggs

mRNA was transcribed in vitro from the NotI-digested anti-ouro1, anti-ouro2, and anti-Foxn1 TALEN constructs using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE SP6 kit (Ambion) and dissolved in Nuclease-Free Water (Ambion). Fertilized eggs were injected with 4 nl of 100–200 ng/µl each of TALEN mRNA and 25–50 ng/µl mCherry mRNA (Nakajima & Yaoita 2013). The embryos were raised at 22–24°C in 0.1 × MMR {MMR; 100 mM NaCl/2 mM KCl/2 mM CaCl2/1 mM MgCl2/5 mM HEPES (pH 7.4)} containing 0.1% BSA and 50 µg/ml gentamicin.

DNA purification

Ten three-day-old F0 embryos were homogenized in 180 µl of 50 mM NaOH and incubated for 10 min at 95°C. The homogenate was neutralized by 20 µl of 1 M Tris-Cl (pH 8.0) and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was mixed with phenol vigorously and centrifuged. The aqueous phase was transferred into a new tube, mixed with chloroform, and centrifuged. The aqueous phase was stored for PCR.

Genomic DNA was extracted from an amputated tail tip of an F1 tadpole using the SimplePrep reagent for DNA (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Mutation analysis

A DNA fragment containing the anti-ouro1 TALEN target sites was amplified using the EmeraldAmp MAX PCR Master Mix (TaKaRa), genomic DNA from F0 embryos, and the primers (ouro1-F1 and ouro1-R1) with a three-step protocol {(95°C, 30 s; 55°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min) × 30}. The amplicon was subcloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), and the nucleotide sequence was subsequently determined. A target DNA fragment of anti-ouro2 TALEN was amplified similarly using F0 genomic DNA and primers (ouro2-F1 and ouro2-R1) with a three-step protocol {(95°C, 30 s; 60°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min)×30}. A target DNA fragment of anti-Foxn1 TALEN was amplified using F0 genomic DNA and primers (Foxn1-F1 and Foxn1-R1) with the same protocol.

A target DNA fragment of anti-ouro1 TALEN was amplified using F1 genomic DNA and primers (ouro1-F2 and ouro1-R2) with a three-step protocol {(95°C, 30 s; 60°C, 30 s; 72°C, 30 s) × 35}. The amplicon was recloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector, and the nucleotide sequence was determined. When only one target sequence was observed in F1 DNA, PCR was performed using KOD FX Neo (TOYOBO) and primers (ouro1-F3 and ouro1-R3) with a three-step protocol {(95°C, 30 s; 60°C, 30 s; 72°C, 3 min 30 s)×30}. A target DNA fragment of anti-ouro2 TALEN was amplified using F1 DNA and primers (ouro2-F2 and ouro2-R2) with a three-step protocol {(95°C, 30 s; 60°C, 30 s; 72°C, 30 s) × 35}. A target DNA fragment of anti-Foxn1 TALEN was amplified using F1 DNA and primers (Foxn1-F2 and Foxn1-R2) with the same protocol. The primer sequences used for mutation analysis are shown in Table S1 in Supporting information.

Western blot analysis

Anti-Ouro1 and anti-Ouro2 serums were prepared by immunizing rabbits with the synthetic peptides QVKFDEDSGATKDL and SDSGFQKKESSTEL, respectively (GenScript) (Fig. S8 in Supporting information). Tadpole skin was excised, homogenized and sonicated in SDS buffer (Okada et al. 2012), and 10 µg of protein was loaded and subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. A blot was probed with the rabbit anti-Ouro1 or anti-Ouro2 antiserum diluted 1:1000. A phosphatase-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (KPL) diluted 1:10,000 was used as a secondary antibody. Reactive bands were visualized by treatment with CDP-Star Chemiluminescence Reagent (PerkinElmer). A blot was stripped in 25 mM glycine (pH 2.5)-1% SDS for 30 s, followed by incubation with a rabbit anti-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, A2066) diluted 1:1000 as a first antibody and a phosphatase-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody as a secondary antibody.

Flow cytometry and immunofluorescence staining

Spleens were dissected from anesthetized frogs and broken up using a loose-fitting plastic homogenizer to prepare cell suspension. Immunofluorescence staining was performed as previously described (Nagata 1986). The spleen cells were reacted with undiluted hybridoma supernatant containing mouse monoclonal anti-Xenopus CD8 antibodies, AM22 and F17, from Xenopus research resource for immunobiology (https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/microbiology-immunology/xenopus-laevis.aspx), stained with 1:1000 dilution of Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgM (Life Technologies), and analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Electronic gates were set by forward and side scatter to delineate lymphoid cells, 3000 to 6000 gated counts were accumulated, and the results are shown as histograms with the number of cells on the y-axis and logarithmic unit of fluorescence intensity on the x-axis.

Transplantation of skin graft

Ventral skin grafts (2 mm×2 mm) were excised from both the Ivory Coast and the Nigerian H (Yasuda) strains of X. tropicalis frogs and transplanted to the dorsal side of the trunk of the wild-type and Foxn1-knockout frogs of the Ivory Coast strain. Frogs were maintained at 26 to 28°C. Photographs were taken every week.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. H. Ogino for allowing K.N. to visit his laboratory to learn the microinjection technique using X. tropicalis, Dr. D. Voytas for supplying the Golden Gate TALEN and the TAL effector kit (Addgene, #1000000016), Dr. S. Nagata for technical advice, and Ms. T. Nakajima for her technical assistance and frog husbandry. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (Grant Numbers 25430089 and 26440057 to K.N. and Y.Y.) and by a grant from National Institutes of Health (Grant Number R24-AI-059830 to J.R.).

References

- Berry DL, Schwartzman RA, Brown DD. The expression pattern of thyroid hormone response genes in the tadpole tail identifies multiple resorption programs. Dev. Biol. 1998;203:12–23. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DD, Wang Z, Furlow JD, et al. The thyroid hormone-induced tail resorption program during Xenopus laevis metamorphosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:1924–1929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cermak T, Doyle EL, Christian M, et al. Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and other TAL effector-based constructs for DNA targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das B, Schreiber AM, Huang H, Brown DD. Multiple thyroid hormone-induced muscle growth and death programs during metamorphosis in Xenopus laevis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:12230–12235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182430599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edholm ES, Albertorio Saez LM, Gill AL, et al. Nonclassical MHC class I-dependent invariant T cells are evolutionarily conserved and prominent from early development in amphibians. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110:14342–14347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309840110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edholm ES, Grayfer L, Robert J. Evolution of nonclassical MHC-dependent invariant T cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014;71:4763–4780. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1701-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elinson RP, Remo B, Brown DD. Novel structural elements identified during tail resorption in Xenopus laevis metamorphosis:Lessons from tailed frogs. Dev. Biol. 1999;215:243–252. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto K, Nakajima K, Yaoita Y. One of the duplicated matrix metalloproteinase-9 genes is expressed in regressing tail during anuran metamorphosis. Dev. Growth Differ. 2006;48:223–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2006.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto K, Nakajima K, Yaoita Y. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase genes in regressing or remodeling organs during amphibian metamorphosis. Dev. Growth Differ. 2007;49:131–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2007.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertwig O. Uber den Einfluss der Temperature auf die Entwicklung von Rana fusca und Rana esculenta. Arch. Mikorosk. Anat. 1898;51:319–381. [Google Scholar]

- Horton TL, Stewart R, Cohen N, et al. Ontogeny of Xenopus NK cells in the absence of MHC class I antigens. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2003;27:715–726. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(03)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Marsh-Armstrong N, Brown DD. Metamorphosis is inhibited in transgenic Xenopus laevis tadpoles that overexpress type III deiodinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:962–967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izutsu Y, Yoshizato K. Metamorphosis-dependent recognition of larval skin as non-self by inbred adult frogs (Xenopus laevis) Journal of experimental zoology. 1993;266:163–167. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402660211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwagi K, Kashiwagi A, Kurabayashi A, et al. Xenopus tropicalis: an ideal experimental animal in amphibia. Exp. Anim. 2010;59:395–405. doi: 10.1538/expanim.59.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer A, Xiao X, Degauque N, et al. The innate NK cells, allograft rejection, and a key role for IL-15. J. Immunol. 2008;180:7818–7826. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.7818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Y, Guo X, Liu Y, et al. Efficient targeted gene disruption in Xenopus embryos using engineered transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:17484–17489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215421109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukaigasa K, Hanasaki A, Maeno M, et al. The keratin-related Ouroboros proteins function as immune antigens mediating tail regression in Xenopus metamorphosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:18309–18314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708837106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata S. Development of T lymphocytes in Xenopus laevis: appearance of the antigen recognized by an anti-thymocyte mouse monoclonal antibody. Dev. Biol. 1986;114:389–394. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K, Fujimoto K, Yaoita Y. Programmed cell death during amphibian metamorphosis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005;16:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K, Nakai Y, Okada M, Yaoita Y. Targeted Gene Disruption in the Xenopus tropicalis Genome using Designed TALE Nucleases. Zool. Sci. 2013;30:455–460. doi: 10.2108/zsj.30.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K, Yaoita Y. Dual mechanisms governing muscle cell death in tadpole tail during amphibian metamorphosis. Dev. Dyn. 2003;227:246–255. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K, Yaoita Y. Comparison of TALEN scaffolds in Xenopus tropicalis. Bio. Open. 2013;2:1364–1370. doi: 10.1242/bio.20136676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehls M, Pfeifer D, Schorpp M, Hedrich H, Boehm T. New member of the winged-helix protein family disrupted in mouse and rat nude mutations. Nature. 1994;372:103–107. doi: 10.1038/372103a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J. Normal table of Xenopus laevis. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa A, Hayashi H. Spatial, temporal and hormonal regulation of programmed muscle cell death during metamorphosis of the frog Xenopus laevis. Differentiation. 1995;59:207–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1995.5940207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M, Nakajima K, Yaoita Y. Translational regulation by the 5’-UTR of thyroid hormone receptor α mRNA. J. Biochem. 2012;151:519–531. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvs026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffeld M, Schultess J. Genes coding for intermediate filament proteins closely related to the hagfish "thread keratins (TK)" alpha and gamma also exist in lamprey, teleosts and amphibians. Exp. Cell Res. 2006;312:1447–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Ohshima M, Morohashi M, Maeno M, Izutsu Y. Ontogenic emergence and localization of larval skin antigen molecule recognized by adult T cells of Xenopus laevis: Regulation by thyroid hormone during metamorphosis. Dev. Growth Differ. 2003;45:77–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.2003.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber R. Induced metamorphosis in isolated tails of Xenopus larvae. Experientia. 1962;18:84–85. doi: 10.1007/BF02138272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaoita Y, Nakajima K. Induction of apoptosis and CPP32 expression by thyroid hormone in a myoblastic cell line derived from tadpole tail. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:5122–5127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.5122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zecher D, van Rooijen N, Rothstein DM, Shlomchik WD, Lakkis FG. An innate response to allogeneic nonself mediated by monocytes. J. Immunol. 2009;183:7810–7816. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.