Abstract

Introduction

With increasing age of the heart failure population, it is important to understand the potential role for orthotopic heart transplant (OHT) in the elderly. We examined recipient and donor characteristics and long-term outcomes of older OHT recipients in the US.

Methods

Using the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database, we identified OHT recipients from 1987-2014 and stratified them by age 18-59, 60-69, and ≥70. We compared baseline characteristics of recipients and donors, and assessed outcomes across groups.

Results

During this period, 50,432 patients underwent OHT; 71.8% (N=36,190) were 18-59yo, 26.8% (N=13,527) were 60-69yo, and 1.4% (N=715) were ≥70yo. Comparing the ≥70yo and 60-69yo groups, older patients had higher rates of ischemic etiology (53.6% vs 44.9%) and baseline renal dysfunction (61.4% vs 56.4%), and at the time of OHT were less likely to be currently hospitalized (45.0% vs. 50.9%) or supported with LVAD therapy (21.0% vs. 28.3%). Older recipients received organs from older donors (median age 36 vs. 30) who were more likely to have diabetes and substance use. After OHT, the median length of stay was similar between groups. At one year, of patients alive, those ≥70yo had fewer rejection episodes (17.8%) compared to those 60-69yo (29.5%). Five-year mortality was 26.9% for recipients age 18-59, 29.3% for age 60-69, and 30.8% for age ≥70.

Conclusions

Despite advanced age and less ideal donors, OHT recipients in their seventies had similar outcomes to recipients in their sixties and selected older should not routinely be excluded from consideration for OHT.

Introduction

The risk of heart failure increases with age.1 As the prevalence of older patients with heart failure grows, the potential role for orthotopic heart transplant (OHT) in elderly patients requires further evaluation. Historically, heart transplant was only offered to younger patients without significant comorbidities. Prior guidelines suggested that while patients older than age 50 could be considered for transplantation, the risk of adverse outcomes could be higher with increasing age.2 While patients in their sixties were routinely evaluated for transplant, until recently septuagenarian patients were considered too old for transplant.

In 2006, however, the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplant (ISHLT) issued updated guidelines on patient selection for heart transplantation which included consideration of adults into their seventies.3 In the United States, transplantation of older adults is increasingly performed, but limited contemporary data exist regarding outcomes for elderly patients.4-8 To evaluate transplantation in older adults, we used data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) to analyze the demographics and outcomes of patients ≥70 years of age compared with patients 60-69 years of age and 18-59 years of age at the time of cardiac transplant.

Methods

Data collection and Study population

This was a retrospective cohort study utilizing transplant data from the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN) Standard Transplant Analysis and Research database provided by UNOS. This is a comprehensive database that includes information on all patients who underwent cardiac transplantation in the United States, and the donors whose organs were received by those recipients.9-11 The study population consisted of adult patients (≥18 years old) who underwent a primary or re-do heart transplantation between January 1, 1987 and March 31, 2014. Patients who underwent combined heart-lung transplant were excluded from this analysis. The Duke University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was 5-year mortality. Other outcomes of interest included length of hospital stay after transplant, episodes of graft rejection, and hospitalizations in the first post-transplant year, and 1-year and 5-year renal dysfunction, stroke, and lymphoproliferative disease. Graft rejection was defined as an episode of rejection requiring medical treatment.12 Renal dysfunction was defined as the need for chronic dialysis.

Statistical analyses

We identified all adult patients who underwent OHT from January 1, 1987 through March 31, 2014, and stratified them into three groups based on age at the time of transplant: 18-59 years old, 60-69 years old, and ≥70 years old. These age groups have been used in prior analyses, and mirror the changes in ISHLT recommendations over time.2,3,5-9 We calculated the frequency of heart transplants by age group for each year. Baseline characteristics of transplant recipients were described using means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Variables were compared across groups using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Donor characteristics were described and compared using similar methods. In addition, 1 and 5 year outcomes were measured and differences in groups were calculated using the chi-square rank based group means score statistics. Kaplan-Meier methods were used to estimate survival. Survival was compared across groups using the log-rank test.

Multivariable proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate the association between age groups and 5-year mortality among heart transplant patients. Outcomes were adjusted for select baseline characteristics of transplant recipient and donor, chosen a priori based on prior studies and clinical relevance.8-10,13,14 Single imputation was used for missing values. Missing values for continuous variables were imputed to the median, and missing values for categorical variables were imputed to the most frequent category. Two models were created, one using the study period from 1995 to 2014, and the other using a more recent cohort from 2004 through 2014 to account for variables not collected prior to 2004, specifically left ventricular assist device (LVAD) use and Centers for Disease Control (CDC) high risk donor status.

Results

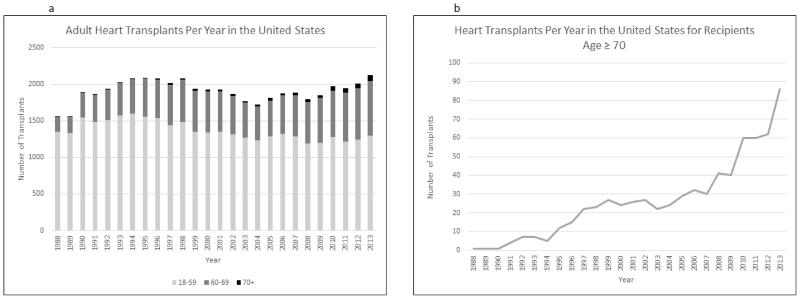

Based on OPTN data as of June 6, 2014, from January 1987 through March 2014, 50,432 patients underwent OHT in the United States, of which 71.8% (N=36,190) were 18-59 years old, 26.8% (N=13,527) were 60-69 years old, and 1.4% (N=715) were ≥70 years old. The median age of heart transplant recipients in the oldest cohort was 71 years old and the maximum age was 79 years old. While the total number of heart transplants performed each year has remained relatively stable over time, the number of heart transplant recipients in their seventies has increased, most notably after 2006 (Figure 1a/1b). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristic of heart transplant recipients by age group. Across all ages, the majority of patients were White and male. Comparing the ≥70 year old group to the 60-69 year old and 18-59 year old group, the oldest group had highest rates of type II diabetes (16.3% vs. 14.9% vs. 8.1%) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage ≥3 (61.4% vs 56.4% vs 35.1%). More than half (52.4%) of recipients in their seventies had a history of CABG. At the time of OHT, the oldest patient group was the least likely to be currently hospitalized (≥70 yo: 45.0% vs. 60-69 yo: 50.9% vs. 18-59 yo: 54.5%) or supported with an LVAD (21.0% vs 28.3% vs 28.6%).

Figure 1.

Frequency of Heart Transplantation from 1988 to 2013

Panel A shows the frequency of heart transplantation by age group from 1988 to 2013.

Panel B shows the frequency of heart transplantation for recipients ≥70 years of age from 1988 to 2013.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Heart Transplant Recipients.

| Variable | N | Age 18-59 | N | Age 60-69 | N | Age ≥70 | P- value1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | |||||||

| Gender, Male, No (%) | 36,190 | 27,030 (74.7) | 13,527 | 11,178 (82.6) | 715 | 644 (90.1) | <.001 |

| Race, White, No (%) | 36,163 | 26,860 (74.3) | 13,522 | 11,359 (84.0) | 715 | 623 (87.1) | <.001 |

| Ischemic etiology, No (%) | 36,189 | 8,449 (23.4) | 13,526 | 6,067 (44.9) | 715 | 383 (53.6) | <.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), median (25th, 75th) 2 | 24,866 | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) | 10,682 | 1.3 (1.0, 1.6) | 665 | 1.3 (1.1, 1.6) | <.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2), median (25th, 75th) 2 | 24,864 | 68.4 (52.0, 88.0) |

10,681 | 58.9 (45.0, 72.3) |

665 | 56.9 (45.1, 69.6) |

<.001 |

| CKD stage ≥3, No (%) 2 | 24,864 | 8,714 (35.1) | 10,681 | 6,022 (56.4) | 665 | 408 (61.4) | <.001 |

| Condition at time of transplant, No (%) | 36,081 | 13,483 | 709 | <.001 | |||

| Not hospitalized | 16,409 (45.5) | 6,619 (49.1) | 390 (55.0) | ||||

| Hospitalized, not in intensive care unit | 5,187 (14.4) | 1,884 (14.0) | 96 (13.5) | ||||

| In intensive care unit | 14,485 (40.2) | 4,980 (36.9) | 223 (31.5) | ||||

| History, No (%) | |||||||

| Diabetes 2 | 25,788 | 11,100 | 688 | <.001 | |||

| Type II | 2,085 (8.1) | 1,650 (14.9) | 112 (16.3) | ||||

| Type I | 353 (1.4) | 190 (1.7) | 10 (1.5) | ||||

| Type Unknown | 2,543 (9.9) | 1,245 (11.2) | 37 (5.4) | ||||

| Type Other | 36 (0.1) | 16 (0.1) | 0 | ||||

| Diabetes status unknown | 335 (1.4) | 142 (1.3) | 12 (1.7) | ||||

| No | 20,416 (79.2) | 7,857 (70.8) | 517 (75.2) | ||||

| Hypertension 3 | 16,787 | 5,871 (36.2) | 6,502 | 2,729 (43.9) | 279 | 110 (40.7) | <.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease 3 | 16,888 | 609 (3.6) | 6,533 | 279 (4.3) | 282 | 11 (3.9) | 0.02 |

| Peripheral vascular disease 3 | 16,833 | 509 (3.1) | 6,524 | 297 (4.8) | 280 | 11 (4.1) | <.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 3 | 16,913 | 454 (2.8) | 6,548 | 286 (4.6) | 281 | 7 (2.6) | <.001 |

| Any prior malignancy 2 | 25,186 | 1,053 (4.2) | 10,859 | 801 (7.4) | 673 | 59 (8.8) | <.001 |

| Prior cardiac surgery 4 | 2,606 | 1,341 | 105 | ||||

| Coronary artery bypass grafting only | 390 (15.0) | 447 (33.3) | 55 (52.4) | <.001 | |||

| Valve replacement/repair only | 164 (6.3) | 84 (6.3) | 5 (4.8) | ||||

| Other (including multiple surgeries) | 2,052 (78.7) | 810 (60.4) | 45 (42.9) | ||||

| Life Support at time of transplant, No (%) | |||||||

| Extra corporeal membrane oxygenation 5 | 24,301 | 143 (0.6) | 10,592 | 39 (0.4) | 681 | 3 (0.4) | 0.01 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 36,190 | 2,087 (5.8) | 13,527 | 757 (5.6) | 715 | 44 (6.2) | 0.57 |

| Prostaglandins 5 | 24,301 | 49 (0.2) | 10,592 | 15 (0.1) | 681 | 0 | 0.14 |

| Intravenous inotropes 2 | 25,832 | 12,093 (46.8) | 11,118 | 5,214 (46.9) | 688 | 304 (44.2) | 0.80 |

| Inhaled Nitric Oxide | 36,190 | 45 (0.1) | 13,527 | 17 (0.1) | 715 | 0 | 0.83 |

| Ventilator | 36,190 | 1,017 (2.8) | 13,527 | 357 (2.6) | 715 | 22 (3.1) | 0.39 |

| Ventricular assist device at time of transplant 4 | 11,557 | 5,623 | 461 | <.001 | |||

| Left ventricular assist device | 3,302 (28.6) | 1,593 (28.3) | 97 (21.0) | ||||

| Right ventricular assist device | 34 (0.3) | 16 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | ||||

| Left + Right ventricular assist devices | 489 (4.2) | 109 (1.9) | 7 (1.5) | ||||

| Total artificial heart | 153 (1.3) | 45 (0.8) | 1 (0.2) | ||||

| None | 7,579 (65.6) | 3,860 (68.7) | 355 (77.0) |

P-values are based on chi-square rank based group means score statistics for all categorical row variables and chi-square 1 df rank correlation statistics for all continuous/ordinal row variables.

Excludes patients registered before Apr 1, 1994

Excludes patients registered before Apr 1, 1994 and after Jan 1, 2007

Excludes patients registered before Jun 30, 2004

Excludes patients registered before Apr 1, 1995

Table 2 reports characteristics of organ donors. Recipients aged ≥70 received organs from older donors (median donor age 36 [25th, 75th: 23, 48]) compared with recipients aged 60-69 (median donor age 30 [21, 43]) and those aged 18-59 (median donor age 28 [20, 39]). Recipients aged ≥70 were the most likely to receive organs from donors considered high risk for transmission of disease, as defined by the CDC, due to history of hemophilia, high-risk sexual behaviors, intravenous drug use, or incarceration. Furthermore, donors for older recipients were more likely have a history of tobacco, alcohol, and cocaine use. Across all groups, donors most commonly died from head trauma, but donors for the oldest recipients were comparatively more likely to die from stroke vs. donors for the 60-69 year old age group and the 18-59 year old age group (30.9% vs 27.5% vs 24.6%). Donors for older recipients also had longer ischemic times (3.2 hours [25th, 75th: 2.5, 3.9]) than donors for younger recipients (3.0 hours [2.3, 3.7] for those 60-69 yo and 2.9 [2.2, 3.6] for those 18-59 yo).

Table 2. Characteristics of Organ Donors by Age Group of Transplant Recipients.

| Variable | No avail |

Age 18-59 | No avail |

Age 60-69 | No avail |

Age ≥70 | P- value1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor Characteristic | |||||||

| Gender, Male, No (%) | 36,190 | 25,647 (70.9) | 13,527 | 9,498 (70.2) | 715 | 479 (67.0) | 0.05 |

| Age (years), Median (25th, 75th) | 36,190 | 28 (20, 39) | 13,525 | 30 (21, 43) | 715 | 36 (23, 48) | <.001 |

| Age ≥35, No (%) | 36,190 | 12,535 (34.6) | 13,525 | 5,607 (41.5) | 715 | 382 (53.4) | <.001 |

| Age ≥45, No (%) | 36,190 | 5,302 (14.7) | 13,525 | 2,882 (21.3) | 715 | 222 (31.1) | <.001 |

| CDC high risk, No (%) 2,3 | 9,294 | 971 (10.5) | 4,750 | 476 (10.0) | 409 | 65 (15.9) | 0.61 |

| Tattoos present, No (%) 4 | 9,277 | 3,955 (42.6) | 4,757 | 2,029 (42.7) | 408 | 166 (40.7) | 0.80 |

| Donor History | |||||||

| History of diabetes, No (%) 5 | 9,287 | 277 (3.0) | 4,745 | 162 (3.4) | 408 | 27 (6.6) | 0.01 |

| Insulin dependence, No (%) 5 | 276 | 117 (42.4) | 162 | 69 (42.6) | 27 | 16 (59.3) | 0.40 |

| History of cigarette use, No (%) 5 | 9,233 | 1,280 (13.9) | 4,709 | 760 (16.1) | 407 | 83 (20.4) | <.001 |

| Cigarette use in last 6 months, No (%) 5 | 1,275 | 1,157 (90.8) | 755 | 689 (91.3) | 83 | 74 (89.2) | 0.89 |

| Heavy alcohol use, No (%) 3 | 9,161 | 1,359 (14.8) | 4,696 | 757 (16.1) | 404 | 82 (20.3) | 0.005 |

| History of cocaine use, No (%) 4 | 9,117 | 1,302 (14.3) | 4,659 | 698 (15.0) | 402 | 77 (19.2) | 0.05 |

| Cocaine use in last 6 months, No (%) 4 | 1,116 | 558 (50.0) | 587 | 284 (48.4) | 69 | 37 (53.6) | 0.75 |

| History of other drug use, No (%) 5 | 9,193 | 3,761 (40.9) | 4,690 | 1,995 (42.5) | 405 | 170 (42.0) | 0.07 |

| Other drug use in last 6 months, No (%) 5 | 3,316 | 2,354 (71.0) | 1,768 | 1,234 (69.8) | 155 | 114 (73.6) | 0.58 |

| Combo smoking, alcohol, cocaine, other drugs, No (%) 3 |

9,304 | 117 (1.3) | 4,764 | 78 (1.6) | 409 | 8 (2.0) | 0.04 |

| Donor Transplant Variables | |||||||

| Cardiac arrest with downtime, No (%) 4 | 9,305 | 611 (6.6) | 4,766 | 319 (6.7) | 409 | 35 (8.6) | 0.42 |

| LVEF (%), Median (25th, 75th) 4 | 9,258 | 60 (55, 65) | 4,754 | 60 (55, 65) | 404 | 60 (55, 65) | 0.82 |

| Cause of death, No (%) | 36,114 | 13,500 | 715 | <.001 | |||

| Head trauma | 19,633 (54.4) | 7,269 (53.8) | 333 (46.6) | ||||

| Cerebrovascular/Stroke | 8,875 (24.6) | 3,718 (27.5) | 221 (30.9) | ||||

| Anoxia | 3,365 (9.3) | 1,423 (10.5) | 130 (18.2) | ||||

| CNS tumor | 272 (0.8) | 118 (0.9) | 8 (1.1) | ||||

| Other | 3,969 (11.0) | 972 (7.2) | 23 (3.2) | ||||

| Ischemic time (hours), Median (25th, 75th) | 34,458 | 2.9 (2.2, 3.6) | 12,849 | 3.0 (2.3, 3.7) | 675 | 3.2 (2.5, 3.9) | <.001 |

| Gender mismatch between donor and recipient, No (%) |

36,190 | 10,559 (29.2) | 13,527 | 3,780 (27.9) | 715 | 213 (29.8) | 0.01 |

P-values are based on chi-square rank based group means score statistics for all categorical row variables and chi-square 1 df rank correlation statistics for all continuous/ordinal row variables.

High risk defined as history of hemophilia, IV drug use, prostitution, high risk sexual activity, HIV exposure, or jail sentencing.

Excludes donors admitted before Jun 30, 2004

Excludes donors admitted before Oct 25, 1999

Excludes donors admitted before Apr 1, 1994

After OHT, the median length of stay was 15 days (25th, 75th: 10, 23) for both the ≥70 and 60-69 year old groups, and 14 days (10, 21) for the <60 year old group (Table 3). Of patients alive at one year, patients ≥70 years old had lower rates of rejection episodes in the first year (17.8%) compared to patients 60-69 years old (29.5%) and <60 years old (38.2%). The oldest age group also had the fewest hospitalizations in the first year. Of patients alive at five years, rates of dialysis, stroke, and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease were similar between groups.

Table 3. Observed Outcomes of Transplant Recipients by Age Group.

| Variable | No avail | Age 18-59 | No avail |

Age 60-69 | No avail |

Age 70+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow Up Outcomes | ||||||

| Length of Stay Transplant to Discharge, Median (25th, 75th) 1 | 17,229 | 14 (10, 21) | 7,764 | 15 (10, 23) | 555 | 15 (10, 23) |

| Treated for Rejection within 1 year, No (%) | 16,905 | 6,464 (38.2) | 7,151 | 2,106 (29.5) | 427 | 76 (17.8) |

| Rehospitalizations in the First Year, No (%) 2 | 14,558 | 5,869 | 298 | |||

| 2 | 25 (0.2) | 14 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | |||

| 1 | 5,969 (41.0) | 2,292 (39.1) | 111 (37.3) | |||

| 0 | 8,564 (58.8) | 3,563 (60.7) | 186 (62.4) | |||

| If Renal Dysfunction, Chronic Dialysis at 1 year, No (%) 2 | 3,149 | 97 (3.1) | 1,501 | 33 (2.2) | 78 | 1 (1.3) |

| If Renal Dysfunction, Chronic Dialysis at 5 years, No (%) 3 | 2,311 | 182 (7.9) | 939 | 51 (5.4) | 35 | 6 (17.1) |

| Stroke at 1 year, No (%) 2 | 9,445 | 95 (1.0) | 3,369 | 38 (1.1) | 124 | 3 (2.4) |

| Stroke at 5 year, No (%) 3 | 6,257 | 66 (1.1) | 2,005 | 31 (1.5) | 61 | 0 |

| Post-Transplant Lymphoproliferative Disease at 1 Year, No (%) 2 | 187 | 33 (17.7) | 211 | 10 (4.7) | 18 | 2 (11.1) |

| Post-Transplant Lymphoproliferative Disease at 5 Years, No (%) 3 | 355 | 18 (5.1) | 265 | 9 (3.4) | 11 | 0 |

Excludes patients listed before Oct 25, 1999

Among patients alive at 1 year

Among patients alive at 5 years

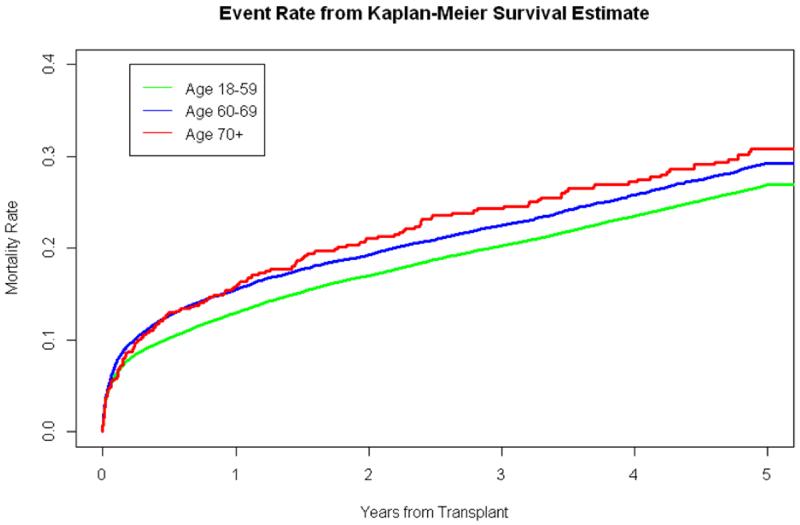

Figure 2 presents 5-year mortality based on age group. Five year Kaplan-Meier estimated mortality rates were 30.8% (95% CI: 27.0-35.0%) in patients ≥70 years old, 29.3% (95% CI: 28.5-30.2%) in patients 60-69 years old, and 26.9% (95% CI: 26.4-27.4%) in adults < 60 years old. Overall, these three groups had different rates of survival (p < 0.001), but survival between the ≥70 year old group and the 60-69 year old groupwas not significantly different (p = 0.48).

Figure 2.

Mortality Rates from Kaplan-Meier Estimates Among Heart Transplant Recipients by Age Group

Table 4a/4b presents unadjusted and adjusted association between age group and 5-year mortality for heart transplant recipients. Table 4a evaluates the association for the time period from April 1, 1995 to March 27, 2014, whereas Table 4b displays the association for the time period from June 30, 2004 to March 27, 2014. Adjusting for donor, recipient, and transplant procedure characteristics, for both time periods, compared to age 18-59, those age 60-69 and age ≥70 at the time of transplant had increased 5-year mortality. In adjusted analysis, for the 1995-2014 time period, patients age ≥70 had a higher risk of death compared to patients age 60-69 (HR 1.2, 95% CI 1.03, 1.41); however in the more recent time period, there was no difference in risk of mortality between the groups (HR 1.13, 95% CI 0.90, 1.41).

Table 4a. Association between Age Groups and 5-Year Mortality among Transplant Recipients from April 1, 1995 to March 27, 2014.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Variable | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

| 5-Year Mortality | Age (60-69) vs. Age (18-59) | 1.12 (1.07, 1.18) | <.001 | 1.13 (1.07, 1.18) | <.001 |

| Age (70+) vs. Age (18-59) | 1.29 (1.10, 1.51) | 0.001 | 1.35 (1.16, 1.58) | <.001 | |

| Age (70+) vs. Age (60-69) | 1.15 (0.98, 1.34) | 0.09 | 1.20 (1.03, 1.41) | 0.02 | |

Adjustment variables: Recipient: gender, race, ischemic etiology, creatinine, condition at transplant, mechanical support (ECMO, IABP, ventilator, or other), pharmacological support (prostaglandins, inotropes, or inhaled NO), diabetes. Donor: ischemic time, age, diabetes, smoking history, cause of death (head trauma, stroke, anoxia, other). Gender mismatch. Year of transplant.

Table 4b. Association between Age Groups and 5-Year Mortality among Transplant Recipients from June 30, 2004 to March 27, 2014.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Variable | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

| 5-Year Mortality | Age (60-69) vs. Age (18-59) | 1.09 (1.02, 1.18) | 0.02 | 1.10 (1.02, 1.19) | 0.02 |

| Age (70+) vs. Age (18-59) | 1.23 (0.99, 1.52) | 0.06 | 1.24 (1.00, 1.54) | 0.05 | |

| Age (70+) vs. Age (60-69) | 1.12 (0.90, 1.40) | 0.30 | 1.13 (0.90, 1.41) | 0.28 | |

Adjustment variables: Recipient: VAD (Yes/No), gender, race, ischemic etiology, creatinine, condition at transplant, mechanical support (ECMO, IABP, ventilator, or other), pharmacological support (prostaglandins, inotropes, or inhaled NO), diabetes. Donor: CDC high risk, ischemic time, age, diabetes, smoking history, cause of death (head trauma, stroke, anoxia, other). Gender mismatch. Year of transplant.

Discussion

We used data from the United Network for Organ Sharing to examine characteristics of heart transplant donors and recipients and post-transplant outcomes, stratified by transplant recipient age. The update of the ISHLT guidelines on heart transplantation ushered in an era of cardiac transplantation of older adults, including those age 70 and above. Over time, the frequency of transplantation in older adults has increased, and in 2013 almost 40% of heart transplants occurred in recipients aged 60 and older with over 4% of heart transplants occurring in recipients age 70 and older. Almost 300 septuagenarians have been transplanted since 2010 when this population was last examined.6

Despite their advanced age, transplant recipients in their seventies had few chronic comorbidities, with the exception of CKD. Moreover, they were less acutely ill at the time of transplantation compared to younger transplant recipients as they were least likely to be hospitalized prior to transplantation. Furthermore, fewer patients in the oldest group were supported with LVAD therapy prior to transplantation. It has been shown that LVAD recipients age 70 and above have worse short-term and midterm survival, and higher rates of stroke and gastrointestinal bleeding after LVAD implantation.15 Despite these risks, the rate of LVAD as a bridge-to-transplant is increasing in this older population.6 Moreover, recent data suggest that transplant outcomes are worse in patients previously supported with either temporary or durable mechanical circulatory support devices compared to patients supported with inotropes only or with no circulatory support prior to transplant.9,13 This is particularly true when device-related complications require emergent transplantation to mitigate the ongoing risk of device support.16 Therefore, our findings highlight that appropriate patient selection is paramount when considering older patients for cardiac transplantation. It appears that current recipient selection strategies at centers that offer transplantation in this population exclude certain high risk groups, such as those with a prior LVAD.

To counter ethical concerns over the distribution of limited donor organs to an older population, transplant guidelines propose allocating organs through alternate donor programs. This practice involves utilization of organs that would traditionally not be accepted for donation or have been turned down by other centers due to donor or organ related factors.3,17 The criteria used for determining an alternate (or extended criteria) donor varies by transplant center, but have shown to effectively maximize the use of donor organs that otherwise would remain unused and therefore extend the option of transplantation to recipients who otherwise may not have been offered this treatment option.18-24 Alternate donor use is not captured in the UNOS database, but our results show that older recipients receive organs from donors with older age, more comorbidities, and other high risk features, such as substance abuse. Furthermore, donors from older recipients had longer ischemic times, suggesting that transplant programs may accept donor organs from a greater distance for these patients.

Despite receiving organs from older and sicker donors and having longer ischemic times, transplant recipients in their seventies had comparable outcomes after transplant compared with younger recipients. Among patients alive at one year, they did not require longer post-transplant hospitalizations, and had fewer rejection episodes and rehospitalizations in the first year. While 5-year survival was lower in the oldest age group, in a contemporary cohort survival in the ≥ 70 year old group was not significantly different from survival in the 60-69 year old group. Our study shows comparable outcomes for patients in their sixties and seventies. Given that it is an increasingly common practice for sexagenarians to be considered for transplantation, our data suggest that older patients should not be routinely excluded from transplantation based on age alone. Select patients in their seventies, specifically those with few co-morbidities, may be appropriate candidates for this therapy.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. This was a retrospective cohort study, so there is a possibility of unmeasured confounders. In addition, there was likely a selection bias in the study population that influenced the results, such that sicker older patients may not have been offered heart transplantation. Furthermore, we only included patients who underwent heart transplantation, so we did not assess survival and outcomes of patients on the heart transplant waiting list. In addition, as this study used data collected in a national registry, we are limited by the data available. Certain data elements were not collected for the entire study period, and there is a high degree of missingness for several outcome variables. In addition, we are limited by the quality, accuracy, and completeness of the data entered into the database. Furthermore, our study was unable to account for regional or center-specific variation in the care of patients before and after transplantation.

Future Research

Appropriate patient selection is a key for success in heart transplantation, and this may be especially true in older patients. Further studies should focus on identifying factors associated with favorable outcomes in older patients and ways to select the right patients to be offered this therapy. Furthermore, with the increase in destination-therapy LVAD in an older population, identifying which patients would be better suited for transplantation versus LVAD therapy could help inform clinical decision-making in the future. In addition, as transplantation of older adults becomes more common, future studies should examine longer-term outcomes in these patients.

Conclusions

Patients ≥70 years old selected for OHT were less acutely ill at the time of transplant and tended to receive organs from older donors with high-risk behaviors. Despite advanced age, these patients had comparatively similar outcomes to younger age groups. Select patients in their seventies should not routinely be excluded from consideration for OHT.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: Dr Cooper was supported by grant T32HL069749-11A1 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclaimer: The data reported here have been supplied by the United Network for Organ Sharing as the contractor for the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, the U.S. Government, or the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures: All authors have no relevant disclosures.

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(4):e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller LW. Listing criteria for cardiac transplantation: results of an American Society of Transplant Physicians-National Institutes of Health conference. Transplantation. 1998;66(7):947–951. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199810150-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehra MR, Kobashigawa J, Starling R, et al. Listing criteria for heart transplantation: International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation guidelines for the care of cardiac transplant candidates--2006. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25(9):1024–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanche C, Takkenberg JJ, Nessim S, et al. Heart transplantation in patients 65 years of age and older: a comparative analysis of 40 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;62(5):1442–1446. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(96)00671-6. discussion 1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanche C, Blanche DA, Kearney B, et al. Heart transplantation in patients seventy years of age and older: A comparative analysis of outcome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;121(3):532–541. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.112831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein DJ, Bello R, Shin JJ, et al. Outcomes of cardiac transplantation in septuagenarians. The J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31(7):679–685. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demers P, Moffatt S, Oyer PE, Hunt SA, Reitz BA, Robbins RC. Long-term results of heart transplantation in patients older than 60 years. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126(1):224–231. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)00055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss ES, Nwakanma LU, Patel ND, Yuh DD. Outcomes in patients older than 60 years of age undergoing orthotopic heart transplantation: an analysis of the UNOS database. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27(2):184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2007.11.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen JG, Kilic A, Weiss ES, et al. Should patients 60 years and older undergo bridge to transplantation with continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices? Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94(6):2017–2024. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber DJ, Wang IW, Gracon AS, et al. The impact of donor age on survival after heart transplantation: an analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) registry. J Card Surg. 2014;29(5):723–728. doi: 10.1111/jocs.12406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss ES, Allen JG, Russell SD, Shah AS, Conte JV. Impact of recipient body mass index on organ allocation and mortality in orthotopic heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28(11):1150–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russo MJ, Chen JM, Hong KN, et al. Survival after heart transplantation is not diminished among recipients with uncomplicated diabetes mellitus: an analysis of the United Network of Organ Sharing database. Circulation. 2006;114(21):2280–2287. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.615708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wozniak CJ, Stehlik J, Baird BC, et al. Ventricular assist devices or inotropic agents in status 1A patients? Survival analysis of the United Network of Organ Sharing database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97(4):1364–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.10.077. discussion 1371-1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taghavi S, Jayarajan SN, Wilson LM, Komaroff E, Testani JM, Mangi AA. Cardiac transplantation can be safely performed using selected diabetic donors. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146(2):442–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atluri P, Goldstone AB, Kobrin DM, et al. Ventricular assist device implant in the elderly is associated with increased, but respectable risk: a multi-institutional study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(1):141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quader MA, Wolfe LG, Kasirajan V. Heart transplantation outcomes in patients with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device-related complications. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;34(1):75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanche C, Kamlot A, Blanche DA, et al. Heart transplantation with donors fifty years of age and older. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;123(4):810–815. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.120009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samsky MD, Patel CB, Owen A, et al. Ten-year experience with extended criteria cardiac transplantation. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(6):1230–1238. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felker GM, Milano CA, Yager JE, et al. Outcomes with an alternate list strategy for heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24(11):1781–1786. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laks H, Marelli D, Fonarow GC, et al. Use of two recipient lists for adults requiring heart transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125(1):49–59. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen JM, Russo MJ, Hammond KM, et al. Alternate waiting list strategies for heart transplantation maximize donor organ utilization. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80(1):224–228. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laks H, Scholl FG, Drinkwater DC, et al. The alternate recipient list for heart transplantation: does it work? J Heart Lung Transplant. 1997;16(7):735–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lima B, Rajagopal K, Petersen RP, et al. Marginal cardiac allografts do not have increased primary graft dysfunction in alternate list transplantation. Circulation. 2006;114(1 Suppl):I27–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.000737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel J, Kobashigawa JA. Cardiac transplantation: the alternate list and expansion of the donor pool. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19(2):162–165. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200403000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]