Abstract

Background

Deficient empathic processing is thought to foster conduct disorder (CD). It is important to determine the extent to which neural response associated with perceiving harm to others predicts CD symptoms and callous disregard for others.

Methods

A total of 107 9-11 year old children (52 female) were recruited from pediatric and mental health clinics, representing a wide range of CD symptoms. Children were scanned with functional magnetic resonance imaging while viewing brief video clips of persons being harmed intentionally or accidentally.

Results

Perceiving harm evoked increased hemodynamic response in the anterior insula (aINS), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), amygdala, periaqueductal gray (PAG), caudate, and inferior parietal lobe (IPL) across all participants. Intentionally-caused, relative to unintentional harm was associated with greater activity in the aINS, amygdala, and temporal pole. There was an inverse association of number of CD symptoms with right posterior insula in both the Harm > No Harm and the Intentional > Unintentional Harm contrasts. Furthermore, an inverse association between callousness and posterior insula activation was found in the Harm > No Harm contrast, with the opposite pattern for reactive aggression scores. An interaction revealed a stronger association in girls between CD symptoms and the right posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS) in the Intentional Harm vs. Unintentional Harm contrast.

Conclusions

Children with greater CD and callousness exhibit dampened hemodynamic response to viewing others being harmed in the insula, a region which plays a key role in empathy and emotional awareness. Sex differences in the neural correlates of CD were observed.

Keywords: Conduct disorder, callousness, affective arousal, emotional empathy, insula, ACC

Introduction

Childhood-onset conduct problems (CP) have serious public health consequences, which impact the child, family and community (Matthys & Lochman, 2009). It is therefore particularly important to examine the neurological mechanisms underlying CP in this age group. Functional magnetic resonance (fMRI) studies have begun to examine neural underpinnings of CP in childhood (Sebastian et al., 2012; Lockwood et al., 2013), but more work is needed, particularly at younger ages. Moreover, studies are needed on sex differences in CP pathophysiology, given evidence of sex differences in prevalence and outcomes (Lahey & Waldman, 2012; Loeber, Burke, Lahey, Winters & Zera, 2000). No prior fMRI work has used an emotional empathy task to examine pre-adolescents with CP, and the few available studies of CP in older children are restricted to males. The current fMRI study examined the relationship between empathy and CP in preadolescent boys and girls.

Past neuroimaging research, conducted almost exclusively in males, presents a mixed picture concerning the relationship between CP and emotional empathy, particularly in response to viewing others in pain, being harmed, or in emotional distress. One set of studies reports reduced affective responsiveness in youth with CP compared to youth without CP, particularly in individuals with elevated callous-unemotional (CU) traits (Cheng et al., 2012; Jones et al., 2010; Lockwood, et al, 2013; Marsh et al., 2013; Sebastian et al., 2012; Stevens, Charman, & Blair, 2001). CU traits are sometimes viewed as early signs of later psychopathy and reflect an important dimension of heterogeneity among children with CP (Frick, Ray, Thornton, & Kahn, 2014). Another set of studies found an opposite profile of responses. These studies reported a positive relationship between levels of aggression and affective responses (Rhee et al., 2013), including a hyper-reactive neural response profile to stimuli depicting of people being harmed (Decety, Michalska, Akitsuki & Lahey, 2009) and atypically elevated threat-circuitry responsiveness (Crowe & Blair, 2008).

Established fMRI methods have been employed for examining the neural underpinnings of affective empathy (or empathic arousal). One particularly widely used paradigm employs visual stimuli depicting individuals being harmed, and some studies further distinguish intentional and accidental harm (Jackson et al., 2005; 2006; Decety & Porges, 2011; Decety, Michalska, Akitsuki, 2008; Decety & Michalska, 2010; Decety, Skelly & Kiehl, 2013). Research with this paradigm in healthy adults and adolescents reveals consistent patterns of activation in a network encompassing sensory regions such as the somatosensory cortex, affective-motivational regions such as the PAG, anterior insula (aINS), medial/anterior cingulate cortex (aMCC), caudate/striatum and amygdala, and regulatory/attention/evaluation regions such as the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) (Cheng et al., 2010; Decety & Jackson, 2004; Decety & Michalska, 2010; Lamm et al., 2007; Lamm, Decety, & Singer, 2011 for a meta-analysis).

Two findings emerge from studies using this paradigm when examining CP. First, an inverse association arises between levels of CU and neural response in affective-motivational regions (Decety, Chen, Harenski, & Kiehl, 2013; Lockwood et al., 2013; Marsh et al., 2013). Second, enhanced responses occur in affective-motivational regions in individuals with reactive aggression (RA), relative to low levels of aggression (Herpetz, 2008). Consistent with such work, in a preliminary study, we also found that adolescents with early-onset CD, relative to adolescents without CD, exhibited greater activation in such regions (Decety, Michalska, Akitsuki, & Lahey, 2009). However, this study did not include pre-adolescents, nor did it assess CU or RA traits, and included only eight participants affected by CD. Moreover, none of these previous studies on emotional empathy examined sex differences, which are known to contribute to heterogeneity in CP (Eme & Kavanaugh, 1995; Fairchild, Hagan, Passamonti, Walsh, Goodyer & Calder, 2014).

The current study is the first to examine associations between variations in brain function and symptoms of CD in both sexes at young ages with a sample large enough to detect large sex differences, if they exist. We measured neural responses to stimuli depicting others being harmed in preadolescent boys and girls with and without CP. Atypical hemodynamic changes were expected in affective-motivational regions identified in previous studies with healthy individuals. On the basis of existing research, we also tested the prediction that CU traits are negatively associated with hemodynamic responses in these regions, whereas RA traits are positively associated with such responses.

Method

Participants and behavioral measures

One hundred sixty nine 9-11 year old children were screened and 126 attended the MRI session. Three children aborted the scan and 2 were excluded due to abnormal structural scans; 14 children were excluded due to excessive movement or scanner artifact, providing data on 107 children in the final analyses. Children were recruited from child mental health and pediatric clinics and were selected based on sex, race-ethnicity, and CD symptoms using the DISC Predictive Scale (DPS) for CD (Lucas et al., 2001). The DPS consists of 8 “stem questions” from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV) CD module (Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000). Children were recruited to either have no symptoms (n = 52), or some symptoms (n = 54) (for a full breakdown see Table S1, available online). Exclusion criteria were pervasive developmental disorder, history of head trauma with loss of consciousness, and safety contraindications for neuroimaging. Participants who assented and whose parents gave written consent under the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board were enrolled.

On the day of scanning, the full DISC-IV was administered to the mother and child by trained interviewers. DISC-IV modules administered to the parent and child assessed 12-month symptoms of CD. The combined number of CP reported by either the parent or the child in the DISC-IV interviews ranged from 0-8. Callousness was assessed using the callousness subscale of the parent-completed Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits (Essau, Sasagawa, & Frick, 2006), comprising 11 items. Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all true) to 3 (definitely true). A mean rating across the scale was calculated for all participants, ranging between 0-2.27. Reactive aggression scores were assessed using the parent version of the Reactive-Proactive aggression scale (Raine, 2006). The correlation between CP and CU traits in this sample was 0.7.

Stimuli

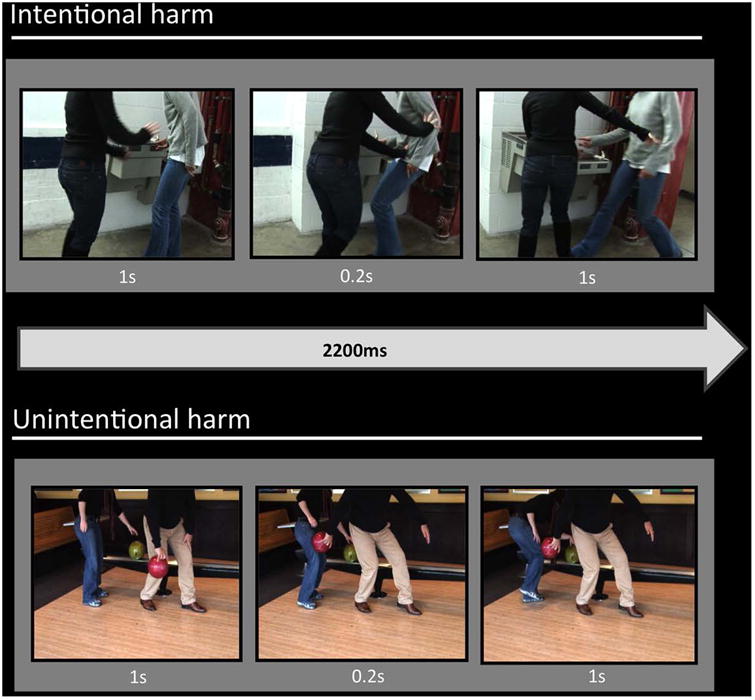

A series of 120 well-validated dynamic visual stimuli depicting intentional and unintentional harm were employed (Decety, Michalska, & Kinzler, 2012). Each scenario consisted of 3 digital color pictures, presented successively to imply motion (Figure 1). The durations of the first, second, and third pictures in each animation were 1000ms, 200ms, and 1000ms, respectively. Five sets of stimuli were present: (1) One person hurting another person intentionally; (2) One person hurting another person unintentionally; (3) One person being hurt with no other person present; (4) Two people in everyday social interactions with no one being hurt; (5) One person in an everyday situation without being hurt. Clips showed situations of varying degrees of harm intensity, and portrayed people of multiple races, ethnic groups, and ages. Importantly, the faces of the protagonists were not visible and thus there was no emotional reaction visible to participants.

Figure 1.

Examples of the stimuli illustrating intentional and unintentional harm scenarios.

Mock scanner training

Prior to scanning, participants were acclimated in a mock scanner. When comfortable, participants viewed 20 stimuli with 4 per condition depicting situations similar to, but distinct from, those they would watch in the actual scanning sessions. Recorded MRI noise was played during mock scanning.

MRI data acquisition

Stimuli were presented with E-prime software (Psychology Software Tools, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA) and a back-projection system. A block design paradigm was used with a total of 24 baseline blocks (17.8s each), during which a fixation cross was presented, and 20 active blocks (20s each), during which stimuli from one of the 5 categories were presented. Stimuli were blocked by condition. The presentation order was counterbalanced across runs and across subjects. Each block consisted of 6 stimuli with a 1.13s inter-stimulus interval, during which a black fixation cross was presented against a gray background.

Participants were shown the stimuli in 2 runs. To avoid confounding motor-related activity in the pre-SMA/SMA, no overt response was required. Instead, participants were instructed to view the stimuli carefully, while eye tracking was collected to confirm attention.

Subjects were scanned using a Philips Achieva 3T MRI system with a Quasar dual gradient system and a 16 channel head coil. Gradient echo-planar images (EPI) were acquired with a Z-shim compensation procedure (Du, Dalwani, Wylie, Claus & Tregellas, 2007). 225 functional images per session were taken using the following parameters: repetition time = 2000ms, echo time = 25ms, 64 × 64 matrix, flip angle 77°, FOV 224mm. Whole brain coverage was obtained with 32 axial slices along the AC-PC line (thickness, 4mm; 0.5mm slice gap, in-plane resolution, 3.5mm × 3.5mm). Total scanning time per run was 7 minutes 30s.

Postscan ratings

After scanning, participants were shown 25% of the stimuli that they had seen during scanning and were asked to respond to 4 questions using a computer-based visual analogue scale (VAS) ranging from 0 to 100. The questions assessed empathic understanding, personal distress, excitement, and enjoyment of another's distress: (1) “How painful was it for the person who was hurt?” (2) “How upset do you feel about what happened?” (3) “How excited were you when you saw that?” and (4) “How much did you enjoy seeing that?” One hundred and fourteen participants (59 female) answered the questions.

Image processing and statistical analyses

Images were inspected by a neurologist (TZ) for structural abnormalities (2 participants excluded). fMRI data were preprocessed and analyzed using SPM12b (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London). Data were processed to remove sources of noise and artifact by correcting for differences in acquisition time between slices, realigning within and across runs to correct for head movement, and normalizing to a standard template in Montreal Neurological Institute space. Normalized data were then spatially smoothed (6mm full-width at half-maximum) using a Gaussian kernel. Finally, realigned data were examined, using the Artifact Detection Tool software package for excessive motion artifacts and correlations between head motion and task, and between global mean signal and task. Outliers were identified in the temporal difference series by assessing between-scan differences (global signal Z-threshold: 3.0, scan to scan movement threshold 0.5mm; rotation threshold: 0.02 radians). These outliers were omitted in the analysis by including a regressor for each outlier. Data from 14 subjects with more than 20% outliers were excluded from further analyses (4F with zero CP; 4F with ≥ 1 CP; 3M with zero CP; 3M with ≥ 1 CP). No concerning correlations between motion and experimental design or global signal and experimental design were identified.

For each subject, a general linear model was applied to the time series (Friston et al, 1995). The effects of stimulus condition were modeled with box-car regressors representing the occurrence of each block type convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function. Six realignment parameters were included as effects of no interest to account for residual motion-related variance. Lastly, regressors for the instructions, cue, and thank you slide periods were entered in the model as regressors of no interest.

Two sets of analyses at the group level were conducted. First, we contrasted harm (collapsing the three harm conditions) versus no harm and intentional versus unintentional harm periods using a one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with condition as the within-group factor. Second, we conducted separate sets of regression analyses for each behavioral measure to determine if individual variations in CP, CU, and RA scores were correlated with regional activations identified in the contrasts just described. Both linear and quadratic terms for the behavior measures were tested. Covariates of no interest in these models were sex, age, race-ethnicity, and the biological mother's education (completion of high school). Maternal education was included both as an indicator of socioeconomic status and because it is robustly associated with the child's intelligence (Bornstein, Hahn, & Wolke, 2013). To remove any potential confounding influence of ADHD symptoms, principal regression analyses were repeated including parent-reported 12-month ADHD symptoms as separate covariates of no interest. We also conducted additional analyses to investigate unique contributions of CU and CP symptoms by controlling the overlap between them in the same regression. The results of these analyses are reported in the supplementary materials available online.

To assess possible sex differences in the relationship between CP and hemodynamic activity, the interactions of each behavioral predictor with sex were tested in additional models. When a significant interaction was observed, we conducted post hoc tests separately among girls and boys.

Two standards for thresholding second level maps were applied. First, we report activations significant at p < .05 with whole-brain family-wise error (FWE) correction. Activations in regions that were not significant with FWE correction, but which reached a threshold of p<0.001, uncorrected, are reported to guide future research and meta-analyses in supplemental tables. Second, we conducted planned analyses of the regional brain correlates of CP and CU, when previous research suggested the involvement of an ROI that was not significant with FWE correction. These planned tests were conducted for specific ROIs in amygdala, aINS, aMCC and pSTS with a threshold of p<0.05, corrected for small volumes (svc). These ROIs were defined from the AAL atlas and mean coordinates from our previous studies using the same stimuli (Decety et al., 2012; Decety & Porges, 2011).

Behavioral ratings

Regressions of post-scan ratings were conducted using SPSS 21 (Chicago, IL). Each participant's ratings were averaged across all scenarios in the two main categories of interest (intentional harm; unintentional harm). To examine whether children's CU and RA scores were associated with ratings for empathy-eliciting scenarios on each of the four question types (empathic accuracy, personal distress, excitement and sadistic enjoyment) for the two categories of stimuli (intentional, unintentional) and to control for shared variance among responses for each of the question types, we computed mixed effects linear models using restricted maximum likelihood estimation.

Mixed effects models were computed with children's ratings as the dependent variable and fixed effects for sex, intentionality and question type. CU and RA scores were included as covariates and allowed to interact with the other factors. Interactions between intentionality and emotional question examined whether children's responses to intentional vs. unintentional scenarios varied as a function of question type, and interactions between CU and RA scores and question type examined whether children's responses to the question types depended on their degree of CU or RA. Three and four-way interactions were also explored. For significant interactions, Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests were used to determine the effects of intentionality on question type. Pearson's r was calculated to decompose any significant interactions between CU and RA traits and question type.

Results

Sample characteristics

Demographic and behavioral characteristics of the sample are reported in Table S1.

Functional MRI results

Group-level comparisons of conditions

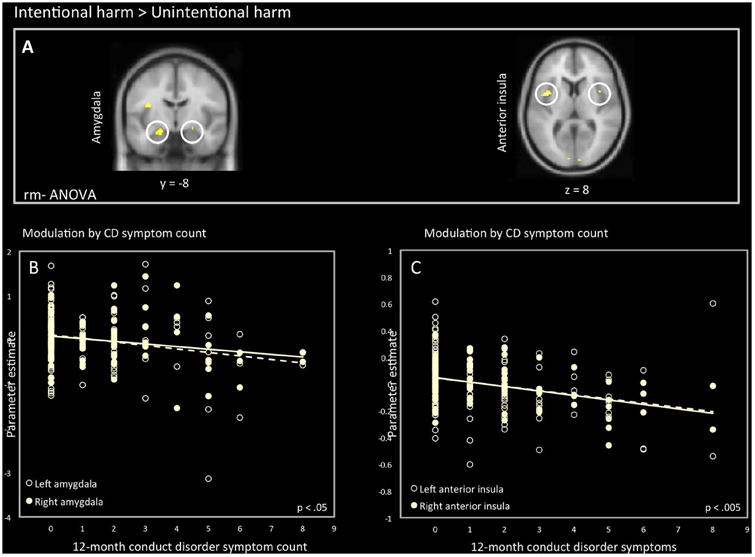

Results of group-level whole-brain analyses tested at p < .05 with FWE correction for the main effects of Harm vs. No Harm are reported in Table S2. Consistent with prior findings in healthy individuals (Lamm et al., 2011), viewing people being harmed relative to neutral interactions evoked significantly greater responses in aINS, ACC, amygdala, PAG, and IPL. In addition, viewing scenes of intentional harm relative to unintentional harm activated aINS, amygdala, and right temporal pole more than viewing unintentionally caused harm (Figure 2A) (Decety et al., 2008; Decety et al., 2012).

Figure 2.

A: Activity in amygdala (L: -20, -8, -16) (R: 22, -6, -16) and anterior insula (L: -34, 20, 8) (R: 38, 26, -8) when viewing intentional harm vs. accidental harm. B: association between amygdala activity and 12-month conduct disorder symptom count. C: association between anterior insula and 12-month conduct disorder symptom count (left R2 = 0.068; right R2 = 0.160).

Whole-brain analyses of behavioral correlates

Associations with CP and CU

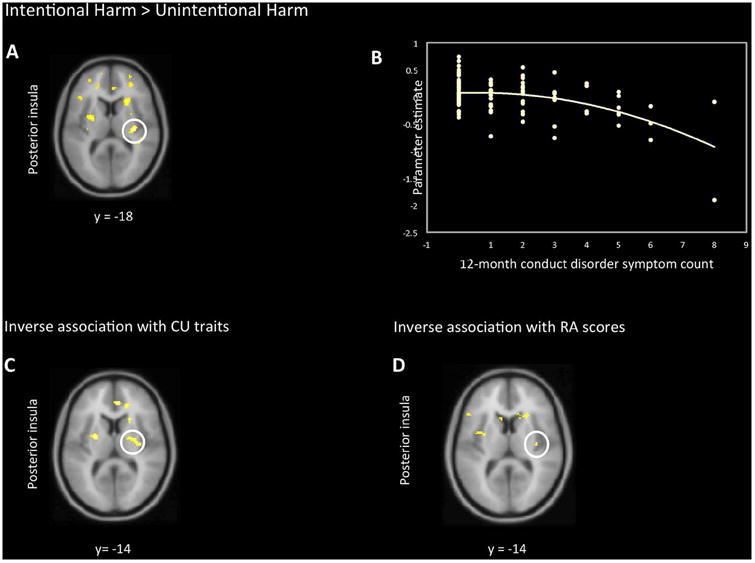

As shown in Table 1 and Figure 3, in the Harm vs. No Harm contrast, regression analyses revealed a significant quadratic term for the inverse association of the number of CP and BOLD signal in right posterior insula. This association reflects particularly low hemodynamic responses in the right posterior insula in children with the highest numbers of CP. For the Intentional > Unintentional Harm contrast, there were similar inverse associations between CP and hemodynamic activation in right posterior insula. In the Harm vs. No Harm contrast, there was a nonlinear inverse association between CU and activation responses in the right posterior insula, as well as right aMCC, indicating a reduced response in these regions at higher levels of CU. Associations at p < .001, uncorrected, are reported in Table S3.

Table 1.

Regions showing a significant association between the number of CD symptoms and callousness scores with hemodynamic response in the two contrasts (n = 107).

| Contrast and Brain Location | Side | MNI Coordinates | Cluster size | t-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| X | y | z | ||||

| Harm > No Harm | ||||||

| CD Symptoms (Inverse Quadratic) | ||||||

| Posterior insula | R | 26 | -20 | 16 | 11 | 5.32 |

| Callousness (Inverse Quadratic) | ||||||

| Posterior insula | R | 28 | -10 | 10 | 12 | 5.42 |

| Intentional > Unintentional Harm | ||||||

| CD Symptoms (Inverse Linear) | ||||||

| Posterior insula | R | 34 | -18 | 10 | 2 | 5.18 |

| CD Symptoms (Inverse Quadratic) | ||||||

| Posterior insula | R | 28 | -22 | 14 | 11 | 5.58 |

t values significant at p < 0.05, FWE whole-brain corrected.

Figure 3.

A inverse association between 12-month CD symptoms and BOLD response in right posterior insula. B scatterplot depicting individual associations between the extracted data from this cluster and 12-month CD symptom count (R2= .20). C inverse association between parent-reported CU traits and BOLD response in right posterior insula. D: inverse association between parent-reported RA scores and BOLD response in right posterior insula.

Effects of ADHD Comorbidity

We repeated the above regression analyses, including ADHD symptoms as covariates of no interest. The analyses showed the same pattern as those reported previously: for the Harm vs. No Harm contrast, the quadratic terms for the association of both the number of CP and CU traits with BOLD response in the posterior insula remained significant (CP: t(100) = 4.92; CU: t(100) = 5.20, both ps < .05, FWE). For the Intentional vs. Unintentional Harm contrast, the association in posterior insula for both linear and quadratic terms also remained significant (linear: t(101) = 4.87; quadratic: t(100) = 4.98, both ps < .05, FWE).

Planned tests of ROIs

Planned tests of associations with ROIs revealed additional regional correlates of CP and CU at p < .05 with svc (Table 2). In the Harm > No Harm contrast, responses in the aMCC varied with the number CP and CU ratings. In the Intentional > Unintentional Harm contrast, both CP and CU covaried with activity in aINS, aMCC, and pSTS. No modulation by CP or CU was observed in amygdala.

Table 2.

Regions of interest that show an association between the number of CD symptoms and callousness scores with hemodynamic response (n = 107).

| Contrast and Location | Side | MNI Coordinates | Cluster size | t-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| x | y | z | ||||

| Harm > No Harm | ||||||

| CD Symptoms (Inverse Quadratic) | ||||||

| Anterior mid cingulate cortex | L | -2 | -16 | 28 | 53 | 4.34 |

| Callousness (Inverse Quadratic) | ||||||

| Anterior mid cingulate cortex | R | 8 | -20 | 38 | 9 | 3.39 |

| Reactive Aggression (Positive Linear) | ||||||

| Anterior insula | R | 34 | -2 | 8 | 9 | 2.64 |

| Anterior insula | L | -36 | 2 | -4 | 6 | 2.83 |

| Anterior mid cingulate cortex | L | -12 | -6 | 46 | 25 | 3.15 |

| Intentional > Unintentional Harm | ||||||

| CD Symptoms (Inverse Linear) | ||||||

| Anterior insula | R | 24 | 20 | 8 | 62 | 4.43 |

| Anterior mid cingulate cortex | L | -6 | -20 | 28 | 20 | 3.81 |

| Posterior superior temporal sulcus | L | 44 | -34 | 8 | 15 | 3.38 |

| Callousness (Inverse Linear) | ||||||

| Anterior insula | R | 24 | 20 | 8 | 40 | 3.83 |

| Anterior cingulate cortex | R | 8 | 32 | -6 | 52 | 4.39 |

| Anterior cingulate cortex | L | -20 | 36 | -8 | 61 | 4.50 |

| Posterior superior temporal sulcus | R | 44 | -32 | 10 | 23 | 3.00 |

t values significant at p < 0.05, with small volume correction.

When 12-month ADHD symptoms were added as covariates of no interest, the same patterns were observed: the quadratic term for the association of the number of CP with BOLD response in aMCC remained significant (t(100) = 3.19, p = .001, svc),

Associations with RA scores

Positive associations were found between RA and responses in the right anterior and right posterior insula and the right SMA in the Harm > No Harm contrast, albeit only at uncorrected levels. For the Intentional Harm vs. Unintentional Harm contrast, the higher the RA scores, the lower the activation in mid and posterior insula and PAG, suggesting less engagement in these regions when observing Intentional harm (see Tables 2 and S4 for details).

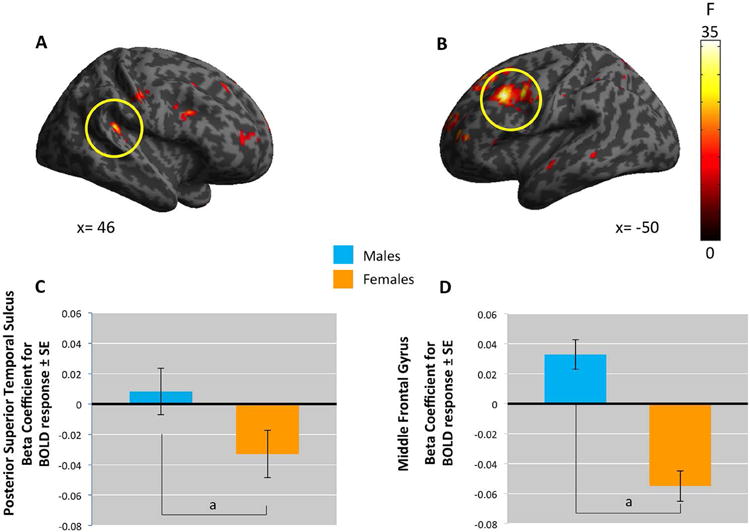

Interaction with sex

A sex × CP interaction was observed in the right STG for the Intentional vs. Unintentional Harm contrast, F(1,100)= 30, p < .05, FWE whole-brain corrected. This interaction was decomposed using post-hoc tests in females and males. In females, but not males, we observed a negative association with right STG (t = 5.02, p < .05). An interaction between sex and the nonlinear CP term also emerged in the pSTS [46,-38,18, F(1,98)= 38.59] and MFG [-50, 14, 38, F(1,98)= 38.62] for Harm > No Harm. In girls we observed a negative association with left MFG (t[98] = 5.45, p < .05), and right pSTS (t[98]= 6.95), p< .05), whereas no association was observed in boys (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Whole-brain analyses indicate sex-by-CP2 interaction.

A. The posterior superior temporal cortex (pSTS, coordinates: 46, -38, 18), B. the middle frontal gyrus (MFG, coordinates: -50,14,38). C. plots the beta coefficients for the BOLD response in pSTS. D. beta coefficients in MFG.

Post-scan ratings

Mixed models revealed main effects for intentionality (F(1,770)= 26.11, p < .001), emotional question type (F(3,770)= 167.34, p < .001) and CU (F(1,110)= 7.05, p < 0.01) on children's subjective ratings of the scenarios. These effects were qualified by a significant intentionality by question type interaction (F(3,770)= 5.887, p < .001) and by a CU by question type interaction F(3,770)= 8.21, p < .001). The three and four-way interactions were not significant. Bonferroni post-hoc tests indicated significant differences between ratings of Intentional vs. Unintentional Harm scenarios for empathic accuracy (F(1,770)= 101.63, p < .001) and personal distress questions(F(1,770)= 66.89), but not for questions about excitement or sadistic enjoyment (F < 1). Specifically, children rated individuals who were hurt intentionally as being more harmed than those hurt unintentionally (74.22 ± 1.98 vs. 50.27 ± 1.98). They also indicated being more upset when watching intentional vs. unintentionally inflicted harm (53.25 ± 1.98 vs. 33.83 ± 1.98). When examining interactions with CU scores, Pearson correlation analyses revealed small, but significant negative correlations between CU and children's upset ratings (r = -.11, p <.01) across both categories of images. The higher children's scores, the less upset they rated themselves when viewing images of people being hurt. No effect of children's RA scores was observed.

Discussion

The present study extends our understanding of atypical emotional empathy in preadolescent children with CP. Three main findings emerged. First, both when viewing Harm vs No Harm and Intentional vs Unintentional Harm scenarios, hemodynamic response in the right insula and aMCC was inversely associated both with the number of conduct problems and with callousness ratings. Second, the opposite pattern was observed with levels of reactive aggression scores, whereby increased RA scores were associated with stronger signal responses in these regions in the Harm vs. No Harm condition. Third, sex-by-CP interactions in STS and MFG were observed. Sex differences in these regions were supported by post hoc tests revealing robust inverse associations in the STS and MFG in females only.

Consistent with previous neuroimaging studies of males with CP (Passamonti et al., 2010; Fairchild et al., 2011), the present study demonstrated that severity of CP is an important dimension in explaining atypical patterns of neural activation. We observed negative nonlinear relationships between CP and activity in a network of brain regions involved in the perception of distress in others including mid and anterior insula, aMCC, MFG and posterior superior temporal gyrus. These results provide further support for dimensional approaches to understanding externalizing psychopathology (Krueger, Markon, Patrick & Iacono, 2005) and suggest that neural atypicalities are most pronounced in individuals with high forms of CP. Of note, in multimodal paradigms with psychopathic adults where perspective-taking is manipulated, reductions in neural responses to interpersonal harm are observed only when observers are instructed to take the perspective of the other and not under a first-person perspective (Decety, Chen, Harenski & Kiehl, 2013; Decety, Skelly & Kiehl, 2013; Decety, Lewis & Cowell, 2015).

We did not detect any significant correlations between CP or CU and amygdala activity, however. Consequently, our results differ from previous results showing reduced amygdala responses to distress cues in male youth with CP and CU traits (Marsh et al., 2008; Jones et al., 2009). This disparity may be because we used stimuli without faces, rather than fearful facial expressions. Future studies should compare these two conditions directly.

The association between callous unemotionality and reduced insula and aMCC response when viewing scenes depicting interpersonal harm is consistent with one other study in adolescent males (Lockwood et al., 2013) and provides additional evidence that callous traits may be of significance in predicting emotional empathic dysfunction (Frick & White, 2008). Meta-analyses of fMRI studies using similar stimuli document that the insula and ACC have a close functional relationship and are likely related to an aversive emotional response elicited in response to viewing harm (Lamm et al., 2011). The association observed here was located in the midposterior portion of the insula. Most closely aligned with the sensory-discriminative components of pain appreciation, this region is known to receive thalamic input associated with the spinothalamic pathway, which is then relayed to more anterior sectors of the insula, where it is integrated with inputs from all sensory modalities, the frontal lobe, and from limbic structures (Decety & Michalska, 2010). Activation in the right anterior insula also was associated with CP and callousness (ROI analysis). Together, these results provide evidence that hemodynamic response in the insula to viewing others being harmed is dampened in children with high levels of both CP and callous disregard for others.

In contrast, RA symptoms were positively associated with activity in posterior insula, and in aMCC, albeit at weaker uncorrected levels. Hyper-activity in this network may reflect heightened emotional responding to provocative stimuli. Thus, CP children with increased RA traits may show reduced emotional empathy because they are highly reactive to others' distress and have problems regulating their emotions (Beauchaine, Katkin, Strassberg, & Snarr, 2001). The present findings suggest that the mechanisms underlying emotional empathy dysfunctions in CP children with high levels of CU traits may be different from those encountered in CP children with high levels of RA traits. Thus, the clinical heterogeneity in CP may help explain some of the inconsistencies across previous studies (Decety et al., 2009; Lockwood et al., 2013; Marsh et al., 2013; Sterzer et al., 2005).

We also found sex-by-CP interactions in STS and MFG at whole-brain corrected levels, which raises the possibility of sex differences in the association of functional neuroanatomy of these regions with CP. If replicated in future studies, this interaction could be important in understanding sex differences in the prevalence and possibly the etiology of CP and delinquent behavior.

Limitations

This study is characterized by a number of important strengths, including the use of a large population-based sample of children and a dimension-based approach to examine the neural underpinnings of viewing harm in both girls and boys with CP with a reliable and well-validated fMRI paradigm. However, a number of limitations should also be noted. CP and CU traits were highly correlated in our sample, thus limiting our ability to fully disentangle the neurobiological correlates of externalizing behavior and CU traits. Even though studies with adults (Hyde et al., 2014) and older youth (Lozier et al., 2014) have found evidence for suppressor effects, our findings remain similar when controlling for the overlap between CP and CU. In this study, the lack of unique relation between CU and neural responses to harm may be due to developmental factors. CD symptoms and CU traits are frequently moderately to substantially correlated in young children. Levels of CU traits may vary during development and many young children with CP have levels of CU traits that are unstable (Pardini, Lochman & Powell, 2007). Delineating more precisely the developmental association between CU traits and CP in middle childhood thus requires more longitudinal cohort studies. Although high levels of psychiatric comorbidity in children with CP group were to be expected given previous epidemiological work (Lehto-Salo, Narhi, Ahonen & Marttunen, 2009), and we controlled for comorbidity of ADHD in our analyses, it will be important to recruit larger non-comorbid CP samples in future research. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the study means that we cannot infer that the atypical neural activation observed plays a causal role in the etiology of CD. Future studies should adopt longitudinal designs to explore whether abnormalities in emotion processing predict the development of CP or resolve following successful treatment.

Conclusion

There is considerable evidence that CD symptoms lie on a continuum (Lahey et al., 1994). Our study represents the first attempt to investigate neural processing of sensitivity to others harm in a large sample that includes both pre-adolescent girls and boys with a wide range of CD symptoms. Importantly, while not all children exhibited symptom threshold for CD, the level of symptoms in the current study still represents substantial risk for serious adverse outcomes. These data contribute to elucidating the functional neuroanatomy of CP in several important ways. Using a well-validated emotional empathy-eliciting paradigm, we show reduced neural response to others' harm in children at high levels of CP and document sex differences in the association between CP and functional neuroanatomy, suggesting early emergence of sexual dimorphism in correlates of aggressive behavior.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Whole brain figure displayed

Table S1: Demographic characteristics of the 107 children in the analyses

Table S2: Significant parameter estimates of BOLD fMRI responses to Pain vs. No Pain

Table S3: Additional regions showing an association between CP symptom count and callousness and hemodynamic response

Table S4: Additional regions showing an association between parent reported Reactive aggressive scores and hemodynamic response

Key points.

Children with conduct problems (CP) often show atypical emotional empathic responding to the distress of others, a finding that may contribute to the aggressive behavior characteristic of conduct disorder (CD).

The current study examines neural response during an affective empathy task (perception of interpersonal harm) in a large sample that includes both pre-adolescent girls and boys along a continuum of CP.

Early onset CP was associated with atypical neural activity in brain regions involved in emotional empathic responding, specifically at high levels of CP.

Results have implications for understanding the neural mechanisms that underlie these emotional responding deficits and may help elucidate the processes associated with the development of CD subtypes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIMH grant R01-MH084934 to J.D. The authors are grateful to Jason M. Cowell for helpful suggestions and to Carrie Swetlik and Talia Reiter for their help with data collection and entry.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

Supporting information: Additional supporting information is provided along with the online version of this article.

The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interests.

References

- Beauchaine TP, Katkin ES, Strassberg Z, Snarr J. Disinhibitory psychopathology in male adolescents: discriminating conduct disorder from attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder through concurrent assessment of multiple autonomic states. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110:610–624. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L. Frustration-aggression hypothesis: examination and reformulation. Psychological Bulletin. 1989;106:59–73. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.106.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJR. The neurobiology of psychopathic traits in youths. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2013;14:786–799. doi: 10.1038/nrn3577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Hahn CS, Wolke D. Systems and cascades in cognitive development and academic achievement. Child Development. 2013;84:154–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01849.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Hung A, Decety J. Dissociation between affective sharing and emotion understanding in juvenile psychopaths. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24:623–636. doi: 10.1017/S095457941200020X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A Review and Reformulation of Social Information-Processing Mechanisms in Childrens Social-Adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115(1):74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe SL, Blair RJR. The development of antisocial behavior: What can we learn from functional neuroimaging studies? Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:1145–1159. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Chen C, Harenski C, Kiehl KA. An fMRI study of affective perspective taking in individuals with psychopathy: imagining another in pain does not evoke empathy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2013;7:489. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Jackson PL. The functional architecture of human empathy. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews. 2004;3:71–100. doi: 10.1177/1534582304267187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Lewis KL, Cowell JM. Specific electrophysiological components disentangle affective sharing and empathic concern in psychopathy. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2015;114:493–504. doi: 10.1152/jn.00253.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Michalska KJ. Neurodevelopmental changes in the circuits underlying empathy and sympathy from childhood to adulthood. Developmental Science. 2010;13:886–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Michalska KJ, Akitsuki Y. Who caused the pain? An fMRI investigation of empathy and intentionality in children. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:2607–2614. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Michalska KJ, Akitsuki Y, Lahey BB. Atypical empathic responses in adolescents with aggressive conduct disorder: a functional MRI investigation. Biological Psychology. 2009;80:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Michalska KJ, Kinzler KD. The contribution of emotion and cognition to moral sensitivity: a neurodevelopmental study. Cerebral Cortex. 2012;22:209–220. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Porges EC. Imagining being the agent of actions that carry different moral consequences: an fMRI study. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:2994–3001. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Skelly LR, Kiehl KA. Brain response to empathy-eliciting scenarios in incarcerated individuals with psychopathy. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:638–645. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Price JM, Bachorowski JA, Newman JP. Hostile attributional biases in severely aggressive adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99(4):385–392. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du YP, Dalwani M, Wylie K, Claus E, Tregellas JR. Reducing susceptibility artifacts in fMRI using volume-selective z-shim compensation. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57(2):396–404. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eme RF, Kavanaugh Sex differences in conduct disorder. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1995;24:406–426. [Google Scholar]

- Essau CA, Sasagawa S, Frick PJ. Callous-unemotional traits in a community sample of adolescents. Assessment. 2006;13:454–469. doi: 10.1177/1073191106287354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild G, Hagan CC, Passamonti L, Walsh ND, Goodyer IM, Calder AJ. Atypical Neural Responses During Face Processing in Female Adolescents With Conduct Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53:677–687. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Ray JV, Thornton LC, Kahn RE. Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:1–57. doi: 10.1037/a0033076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, White SF. Research review: the importance of callous-unemotional traits for developmental models of aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:359–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Poline JB, Grasby PJ, Williams SC, Frackowiak RS, Turner R. Analysis of fMRI time-series revisited. NeuroImage. 1995;2:45–53. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1995.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herpetz S. Emotional processing in conduct disorder: Data from psychophysiology and neuroimaging. European Psychiatry. 2008;23:S9–S9. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde LW, Byrd AL, Votruba-Drzal E, Hariri AR, Manuck SB. Amygdala reactivity and negative emotionality: Divergent correlates of antisocial personality and psychopathy traits in a community sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;123:214–224. doi: 10.1037/a0035467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson PL, Brunet E, Meltzoff AN, Decety J. Empathy and the neural mechanisms involved in imagining how I feel versus how you would feel pain: An event-related fMRI study. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:752–761. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson PL, Meltzoff AN, Decety J. How do we perceive the pain of others: A window into the neural processes involved in empathy. NeuroImage. 2005;24:771–779. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AP, Happe FGE, Gilbert F, Burnett S, Viding E. Feeling, caring, knowing: different types of empathy deficit in boys with psychopathic tendencies and autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:1188–1197. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Marknon KE, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG. Externalizing psychopathology in adulthood: A dimensional-spectrum conceptualization and its implications for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:537–550. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Applegate B, Barkley RA, Garfinkel B, McBurnett K, Kerdyk L, et al. DSM-IV field trials for oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1163–1171. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Waldman ID. Annual Research Review: Phenotypic and causal structure of conduct disorder in the broader context of prevalent forms of psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53:536–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamm C, Nusbaum HC, Meltzoff AN, Decety J. What are you feeling? Using functional magnetic resonance imaging to assess the modulation of sensory and affective responses during empathy for pain. PLoS ONE. 2007;12:e1292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamm C, Decety J, Singer T. Meta-analytic evidence for common and distinct neural networks associated with directly experienced pain and empathy for pain. NeuroImage. 2011;54:2492–2502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood PL, Sebastian CL, McCrory EJ, Hyde ZH, Gu X, De Brito SA, Viding E. Association of callous traits with reduced neural response to others' pain in children with conduct problems. Current Biology. 2013;23:901–905. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Burke JD, Lahey BB, Winters A, Zera M. Oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: a review of the past 10 years, part I. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1468–84. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200012000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozier LM, Cardinale EM, VanMeter JW, Marsh AA. Mediation of the relationship between callous-unemotional traits and proactive aggression by amygdala response to fear among children with conduct problems. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014:627–636. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas CP, Zhang H, Fisher PW, Shaffer D, Regier DA, Narrow WE, et al. The DISC Predictive Scales (DPS): efficiently screening for diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:443–449. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh AA, Finger EC, Fowler KA, Adalio CJ, Jurkowitz IT, Schechter JC, et al. Blair RJ. Empathic responsiveness in amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex in youths with psychopathic traits. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:900–910. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthys W, Lochman JE. Oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder in children. New York: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Jaffee SR, Kim-Cohen J, Koenen KC, Odgers CL, et al. Viding E. Research review: DSM-V conduct disorder: research needs for an evidence base. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:3–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01823.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orobio de Castro B, Veerman JW, Koops W, Bosch JD, Monshouwer HJ. Hostile attribution of intent and aggressive behavior: a meta-analysis. Child Development. 2002;73:916–934. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passamonti L, Fairchild G, Goodyer IM, Hurford G, Hagan CC, Rowe JB, Calder AJ. Neural Abnormalities in Early-Onset and Adolescence-Onset Conduct Disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:729–738. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA, Lochman JE, Powell N. The development of callous-unemotional trait san dantisocial behavior in children: are there shared and/or unique predictors? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:319–333. doi: 10.1080/15374410701444215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SH, Friedman NP, Boeldt DL, Corley RP, Hewitt JK, Knafo A, et al. Zahn-Waxler C. Early concern and disregard for others as predictors of antisocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:157–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02574.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian CL, McCrory EJP, Cecil CA, Lockwood PL, DeBrito SA, Fontaine NMG, Viding E. Neural Responses to Affective and Cognitive Theory of Mind in Children with Conduct Problems and Varying Levels of Callous-Unemotional Traits. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:814–822. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterzer P, Stadler C, Krebs A, Kleinschmidt A, Poustka F. Abnormal neural responses to emotional visual stimuli in adolescents with conduct disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens D, Charman T, Blair RJ. Recognition of emotion in facial expressions and vocal tones in children with psychopathic tendencies. J Genet Psychol. 2001;162:201–211. doi: 10.1080/00221320109597961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F, Brendgen M, Tremblay RE. Reactively and proactively aggressive children: antecedent and subsequent characteristics. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:495–505. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Whole brain figure displayed

Table S1: Demographic characteristics of the 107 children in the analyses

Table S2: Significant parameter estimates of BOLD fMRI responses to Pain vs. No Pain

Table S3: Additional regions showing an association between CP symptom count and callousness and hemodynamic response

Table S4: Additional regions showing an association between parent reported Reactive aggressive scores and hemodynamic response