INTRODUCTION

Large deletions affecting chromosome 13 occur in 50% of multiple myeloma (MM) cases and are associated with poor long-term survival [1]. The role of chromosome 13 deletions in MM has been the focus of intense study, but the tumor suppressor gene(s) have not been conclusively identified [14]. The Retinoblastoma (RB1) gene has been implicated as a candidate tumor suppressor at 13q14 in MM [2]. Previously, we mapped chromosome 13 deletions in MM and found a microdeletion in a t(4;14) positive patient that removed a single exon of RB1 critical for its function [3]. High-resolution genetic studies including single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array studies [4] and whole genome sequencing approaches [5,6] have also found that RB1 is a recurrent deletion target in MM. Of note though, retained RB1 alleles remain un-mutated and expressed in the majority of cases of MM [7]. RB1 is the gene that defined biallelic loss as the sine qua non of tumor suppressor gene function [8], however, given the frequent monoallelic loss of RB1 and the central role of Cyclin D/Rb pathway in MM, if RB1 is the target of chromosome 13 deletion, it remains an enigma why it is infrequently biallelically inactivated [9].

The function of Rb1 as a tumor suppressor has been well-studied, and genetically targeted mice have been invaluable tools in dissecting the role of Rb1 in tumor development [10,11]. Germline deletion of Rb1 is embryonic-lethal with defects in neurogenesis and hematopoiesis [12–14]. Mice engineered with a conditional Rb1 allele develop pituitary tumors, demonstrating the tumor-suppressor activity of Rb1 [15,16]. However, mice with conditional loss of Rb1 do not develop retinoblastoma tumors as was expected from human genetic studies. In mice, two additional Rb family members, p107 and p130 have redundant tumor suppressor function [17–20], thus complicating the study of Rb1’s role in tumorigenesis. The p107 family member is upregulated upon Rb1 loss in the mouse retina and deletion of p107 is necessary before retinoblastoma tumors develop [19].

To identify potential roles of Rb1 in MM pathogenesis, we generated triple transgenic mice with conditional deletion of Rb1 in germinal center (GC) B-cells. We found increased proliferation in Rb1 null B-cells stimulated to undergo class switch recombination (CSR). In vivo, mice with Rb1 deleted in GC B-cells had a lower percentage of splenic B220+ cells and fewer bone marrow antigen specific secreting cells (ASCs) compared to control mice. Our data suggest complete absence of Rb1 in antigen stimulated cells results in hyperproliferation balanced by cell death.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

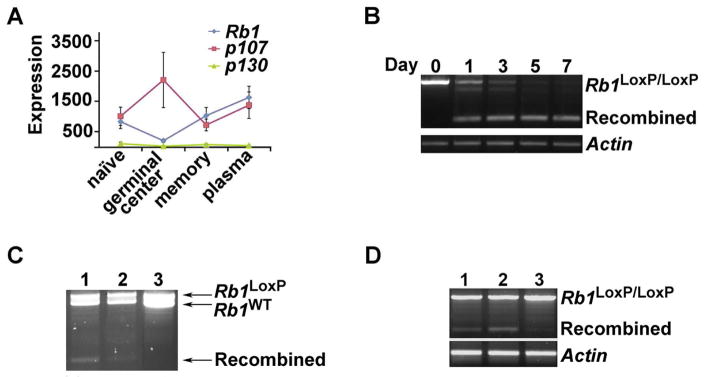

We sought to generate strains of mice with Rb1 function deleted from GC B-cells. The Rb1 family members Rbl1 (p107) and Rbl2 (p130) compensate for Rb1 loss in some cell types,[19] so we examined the transcript expression of all three retinoblastoma family genes at four stages of B-cell development: naive B, GC B, plasma and memory B cells [24]. We found Rb1 and p107, but not p130, were expressed in mature B-cell subsets including GC and plasma cells (Fig. 1A). These data suggested that p107 might compensate for Rb1 loss in GC cells, so we generated triple transgenic mice using the previously characterized conditional Rb1Flox allele, the Cγ1-cre- that express cre recombinase specifically in GC B cells, and a p107 null allele. In this way, we established three strains of mice: Cγ1-Rb1F/F-p107−/−, Cγ1-Rb1F/+-p107−/−, and Cγ1-Rb1+/+-p107−/− (which will be referred to as Rb1F/F, Rb1F/+, and Rb1+/+ for simplicity; Fig S1).

Figure 1. Generation of triple transgenic mice without Rb1 gene function in GC B-cells.

(A) Expression pattern of Rb1 family members in mature B-cell subsets. mRNA microarray expression data (arbitrary units) of Retinoblastoma family members Rb1, p107 and p130 in flow sorted primary late B-cell populations from wild-type mice. [24]. (B) PCR analysis of DNA isolated from Rb1F/F mouse spleen B-cells after ex-vivo stimulation with IL-4 for indicated time points (Day 0 to Day 7). β-actin was used as a loading control. (C) Rb1 recombination in splenic B cells and bone marrow CD138+ cells of Rb1F/+ mouse after NP-CGG immunization by PCR. Lane 1: mouse spleen B-cells, lane 2: mouse bone marrow CD138+ cells, lane 3: mouse tail DNA was used as a negative control. (D) Recombination in a panel of cell types of Rb1F/F mouse after NP-CGG immunization by PCR. Lane 1: mouse bone marrow B220+IgM− cells (early B-cells), lane 2: mouse spleen B-cells, lane 3: bone marrow B220-Ly6G+cells (granulocytes). β-actin is shown as loading control.

Recombination was successful at the Rb1 locus in B-cells from Rb1F/F mice stimulated to undergo CSR ex vivo (Fig. 1B and Fig.S2). Recombination was also detected in vivo in splenic GC cells (B220+GL7+IgG1+), and in post-GC plasma cells (B220−, CD138+) of Rb1F/+ mice (Fig. 1C). Small amounts of recombination were detected in Rb1F/F bone marrow B cells, suggesting small amounts off-target cre expression in pre-GC B-cells. No recombination was detected in myeloid lineage cells (Fig. 1D). To address the off-target effects observed in the Rb1F/F mice, we mated Rb1F/F mice to AID-cre mice, which drive cre expression in GC cells undergoing (CSR). These matings did not yield genotypes at expected mendelian frequencies and we were unable to generate AID-Cre-Rb1F/F-p107−/− mice. This was likely due to embryonic lethality since AID is expressed in embryonic neuronal cells [22] and Rb1 null mice are embryonic lethal due to neuronal defects [12–14].

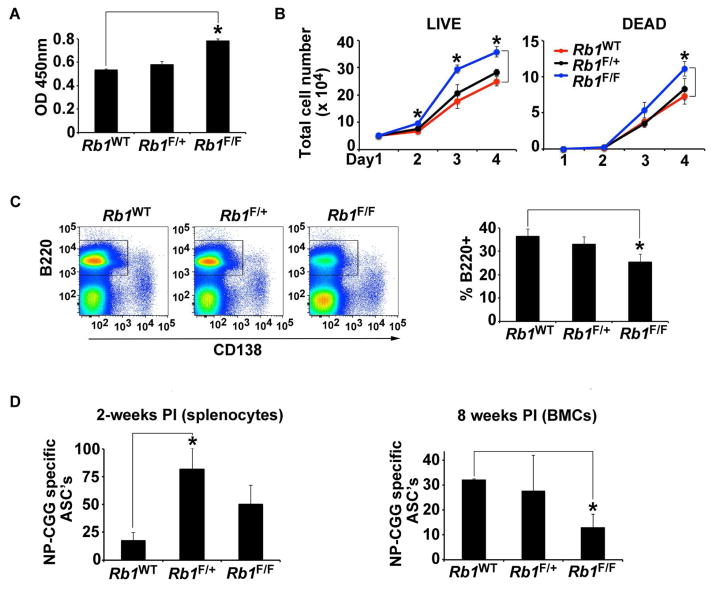

We anticipated cell cycle deregulation in GC B-cells with Rb1 deficiency, so we measured proliferation in naive splenic B cells from our triple transgenic Rb1+/+, Rb1F/+ and Rb1F/F mice stimulated to undergo CSR ex vivo. Proliferation was significantly increased in Rb1F/F spleen cells compared to Rb1+/+controls assessed by both BrdU incorporation (Fig. 2A) and cell growth assays (Fig. 2B) although they did not proliferate past day four of culture (not shown), suggesting the cells were not transformed. We observed significantly more dead cells in Rb1F/F B-cells (Fig. 2B). Our observation that Rb1 deficiency in GC B-cells caused both increased proliferation and cell death, has been seen in other cell types and is consistent with Rb1’s well-known function as a cell cycle check point and apoptotic regulator [10].

Figure 2. Hyperproliferation and cell death of B cells undergoing class switch recombination.

(A) BrdU assay of splenic B-cells isolated from Rb1+/+, Rb1F/+ and Rb1F/Ftriple transgenic mice stimulated with IL-4 and LPS for three days. Equal numbers of cells from each genotype were pulsed for with BrdU and OD at 450nm was measured. Experiment was performed three times in quadruplicate; representative analysis shown. (B) Growth curves of splenic B-cells derived from Rb1+/+, Rb1F/+ and Rb1F/F mice stimulated with IL-4 and LPS. Equal numbers of cells were plated in triplicate on Day 1. Cells were counted each day for three days using trypan blue. Live cells (trypan blue excluded) shown on left and dead cells (trypan blue stained) are shown on left. Experiment was performed three separate times in triplicate; representative analysis shown. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of splenic CD138+ B220− (plasma) cells of Rb1+/+ and Rb1F/F triple transgenic mice two weeks after NP-CGG immunization (left). The average percentage of bone marrow B220+ cells (n= six mice each genotype) was analyzed on separate days (right). (D). ELISA-SPOT assays were performed two weeks post immunization (PI) with NP-CGG on splenocytes (left) and eight weeks PI on whole bone marrow cells (BMCs) isolated from Rb1+/+, CG-Rb1F/+ and Rb1F/F mice. NP-CGG- specific antigen secreting cells (ASCs) were quantitated by counting spots (methods). For the splenocyte analysis, ASCs per 400,000 plated cells in duplicate is shown (n=6 mice per genotype). For the BMC analysis, ASC’s per 460,000 plated cells in duplicate is shown. For Rb1+/+ (n=2); and for Rb1F/+ and Rb1F/F (n=4). For all experiments, error bars are standard error of the mean. Statistical analyses were performed using a 2-tailed, unpaired T-Test. Asterisk (*) indicates p < 0.05

To assess the effect of Rb1 deficiency on GC B cells in vivo, we measured short-term GC splenic B-cell responses following immunization. Mice were stimulated with NP-CGG and two weeks later, B cell subsets were assessed by immunophenotyping using five-color flow cytometry. Despite the ex vivo proliferation we observed, no significant differences were found in immature B cells (IgM+ IgD−), activated B cells (IgM+ IgD+), follicular (IgMlow IgD+), GC B cells (B220+ IgD− GL7+; data not shown), or plasma cells (B220−/low CD138+; Fig. 2C) populations. We did observe a decrease in the percent of B220+ splenocytes isolated from Rb1F/F mice compared to Rb1+/+ control mice suggesting Rb1 deficiency in early B cells may lead to increased apoptosis, but no differences were observed in the percent of B220+CD138+ bone marrow plasma cells across the three mouse strains (Fig. 2C).

We next measured antigen- specific plasma cell responses using NP-CGG ELISA-SPOT assays and splenocytes from each of the three strains of mice. Unexpectedly, the Rb1F/+ mice had an increase of splenic NP-CGG-specific antibody secreting cells (ASC’s) compared to Rb+/+ controls but the Rb1F/F did not. Following successful CSR in GCs, B-cells differentiate to plasma cells and home to the bone marrow. To assess B cell subsets at a later time point (eight weeks post immunization; PI), we measured B and plasma cells in the bone marrow and spleen of the three mouse strains by measuring percentages of each by flow cytometry, as above. No significant changes in any of the B cell subsets we tested was observed (data not shown). To quantitate antigen- specific plasma cell responses, NP-CGG ELISA-SPOT assays were performed using bone marrow cells from each of the three strains of Rb1F/F mice had significantly fewer NP-CGG ASC’s compared to Rb1+/+ mice, suggesting loss of Rb1 in post-GC B cells may induce cell death.

Rb1F/+ and Rb1F/F mice developed normally and appeared healthy. To screen these mice for malignancy, we assessed an array of biomarkers when mice reached the age of twelve months after NP-CGG stimulation. Complete blood counts (CBC), revealed that compared with Rb1F/+ and Rb1+/+ mice, the white blood cell and lymphocyte counts were slightly, but not significantly increased in Rb1F/F mice (Fig.S3). Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) analysis revealed no significant M-proteins in any of the mice (Fig.S4). X-ray analysis was used to to look for lytic bone lesions, a hallmark of MM, but none were detected (Fig.S5). No significant abnormalities were seen in vivo, including chemistry tests (serum creatinine, calcium, blood urea nitrogen,, albumin, and total protein), and histopathological analysis of organs (heart, liver, lung, kidney, spleen; data not shown). These data suggest that no MM or other B-cell malignancy developed in Rb1F/+ or Rb1F/− mice, with twelve months of follow-up.

Together our data demonstrate that Rb1 function is essential for control of proliferation of GC B-cells, but that loss of this tumor suppressor is not sufficient to initiate malignant transformation. Rather, B-cell numbers were decreased in the absence of Rb1 (Fig. 2). The C-gamma driven Cre expression predicts recombination in GC B-cells; however we detected ‘off-target’ recombination in bone marrow B cells (Fig. 1). We also observed fewer NP-CGG specific BM ASC’s in Rb1F/F mice. These results may be explained by the fact that E2F factors activated by Rb1 loss induce apoptosis through p53 in certain cell types [23]. This is consistent with the observation that although haploinsufficiency for RB1 is common, complete loss of RB1 is rare in the absence of other mutations to protect the cells from death.

Additional mutations are required to cooperate with Rb1 loss for malignant transformation of GC B-cells. Our finding that GC B-cells haploinsufficient for Rb1 proliferate in response to antigen stimulation (Fig. 2) suggests that malignant cells may optimize Rb1 dose for best proliferative advantage. This would provide an explanation for frequent monoallelic RB1 loss and rare homozygous deletion in MM. Although RB1 is affected by microdeletions and point mutations [3], large deletions affecting 13q are far more common in MM. Large deletions may facilitate MM growth and survival by simultaneously reducing the expression of RB1 and another 13q gene or genes. One such candidate is DIS3, a 3′ to 5′ RNA exonuclease recurrently mutated in MM and located at chromosome 13q22.1. Notably, DIS3 mutations detected in MM reduce but do not eliminate DIS3 activity. Hypomorphic DIS3 dysregulates the cell cycle through a mechanism that increases centromeric RNA and modification of chromatin structures near centromeres (unpublished data). Our mouse model will be a useful reagent for exploring the role of cooperation between Rb1 loss and reduced Dis3 activity and testing the role of Rb1 loss and MM-associated gain-of-function oncogene mutations.

METHODS

Mouse models

To establish CG-Rb1F/F-p107−/−, CG-Rb1F/+−p107−/− and CG-Rb1WT-p107−/− mouse models that conditionally delete Rb1 in spleen germinal center B cells, we generated strains of mice by breeding Rb1Flox/Flox mice to the Rb family member, p107−/− mice. Rb1Flox/Flox - p107−/− mice were bred to the germinal center specific C-gamma-1 (Cγ1-Cre mice that have the Cre recombinase knocked into the endogenous Cγ1 locus which expressed specifically during B-cell class switch recombination. Rb1F/F and p107−/− mice were backcrossed ten times to C57BL/6J. The p107−/− mice retained their brown color-likely due to the Agouti genes being relatively close on chromosome 2 to p107. The CG mice were on a C57BL/6J background when we obtained them. Rb1 locus recombination was tested by PCR as previously described [14]. Products obtained from Rb1LoxP alleles were 780bp and from Rb1WT alleles were 680bp. Recombined alleles were 260bp. At six weeks of age, all mice were immunized using 1 mg of (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl) acetyl conjugated chicken gamma globulin (NP-CGG; Biosearch Technologies), which was mixed with Freud’s Adjuvant Complete or Incomplete (Sigma-Aldrich) for primary or boosting immunization in 100 μl to inject intraperitoneally to promote germinal center B cell activation and Rb1 conditional deletion. All mice were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions and used according to institutional guidelines.

Ex-vivo Class Switch Recombination (CSR) assay

Murine splenocytes were treated with red blood cell lysing buffer (Sigma), and B cells isolated using CD43 magnetic bead depletion (LD) columns (Miltenyi) Biotech with an AutoMacs pro separator according to the commercial instructions. Splenic B cells were cultured with 20 ng/ml of IL-4 (R&D systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota) and 10μg/ml LPS (Sigma-Aldrich) in B cell medium (RPMI-1640 with L-Glutamine (Cellgro, Manassas, Virginia), 1% HEPES, 1% penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin B, 10% FBS (Hyclone, South Logan, Utah) for indicated times.

Immunophenotyping by flow cytometry

Spleens and bone marrow were harvested from mice, passed through 50μm CellTrics filters (Partec) to generate single cell suspensions, and briefly treated with hypotonic lysis buffer to remove red blood cells. 10×106 cells were then suspended in 0.5mL staining buffer (PBS, 0.5% BSA, 0.05% NaN3) and incubated with the following rat anti-mouse monoclonal antibodies (all purchased from BD Biosciences unless indicated otherwise) in the dark on ice for 30min: APC-Cy7 B220 (RA3-6B2), Brilliant Violet 421 CD138 (281-2), PE GL7 (GL7), FITC IgM (II/41) and PerCP-Cy5.5 IgD (11-26c.2a, BioLegend). Cells were then washed twice with staining buffer, resuspended in 0.5mL and flow cytometric analysis was performed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson), modified with additional lasers (Cytek Development). 1×106 events were collected and FlowJo software (Tree Star) was used for data analysis.

Cell proliferation (BrdU and Cell counting)

For BRDU assays, IL-4 and LPS- treated B cell were cultured (as above) for three days. On the third day proliferation was tested by pulsing 25,000 cells of each genotype with BRDU for two hours using an ELISA BrdU Kit (Cell Signaling) according to company’s instructions. For cell counting, 50,00 cells were plated for each genotype in triplicate on day one. Viable cells were counted using trypan blue exclusion; cells that had taken up the dye were considered dead and also counted. Cells were counted on a hemocytometer.

ELISA-SPOT Assays

MultiScreen nitrocellulose filter plates (EMD Millipore) were coated with 50μg/ml NP16-BSA (Biosearch Technologies) or BSA alone as a control and incubated overnight at 4°C. Splenocytes (2-weeks post immunization) or bone marrow cells (8 weeks post immunization) were seeded at decreasing doses in duplicate. Cells were cultured in 100μl overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2. Wells were washed with PBS with 0.5% TWEEN and stained with biotinylated anti-mouse IgG. Plates were washed and next incubated with Streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (BD Pharmingen). Spots were developed using 3-amino-9-ethyl-carbazole (Sigma). Once spots appeared, the reactions was quenched by rinsing wells with water. Spots were counted using an ImmunoSpot S6 Analyzer (CTL Laboratories).

CBC analysis

Complete Blood Count (CBC) was quantitated using HEMA VET 950 system (Drew Scientific, Texas).

SPEP (Serum Protein electrophoresis) analysis

Serum samples were analyzed by SPEP on Quickgel Chamber apparatus using pre-casted quickGels (Helena Laboratories) according to manufacture’s instruction. Densitometric analysis of the SPEP traces was performed using the clinically certified Helena QuickScan 2000 workstation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We generated triple transgenic mice with Rb1 deletion in germinal center B-cells

Antigen stimulated Rb1 deficient B cells displayed hyperproliferation and cell death

Deletion of Rb1 in germinal center B cells did not induce malignancy

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the Tomasson lab for critical review of the manuscript. We thank the Michael Dyer lab for providing the Rb1LoxP/LoxP and p107−/− mouse strains and the Stefano Casola lab for providing the c-gamma-1 cre mouse strain. We thank Dr. Deborah Novack for the pathology analysis. The Siteman Flow Cytometry Core Musculoskeletal Histology Core and Developmental Biology Histology Core provided excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Barnes Hospital Foundation (MHT) and the NIH R21AG040777 (MHT). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTIONS

ZH, JO, WCW and NM designed and performed experiments. JL, YH and MYS performed experiments. ZH and JO wrote the paper. MHT designed the experiments and wrote the paper.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zojer N, Konigsberg R, Ackermann J, Fritz E, Dallinger S, et al. Deletion of 13q14 remains an independent adverse prognostic variable in multiple myeloma despite its frequent detection by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization. Blood. 2000;95:1925–1930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dao DD, Sawyer JR, Epstein J, Hoover RG, Barlogie B, et al. Deletion of the retinoblastoma gene in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 1994;8:1280–1284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Neal J, Gao F, Hassan A, Monahan R, Barrios S, et al. Neurobeachin (NBEA) is a target of recurrent interstitial deletions at 13q13 in patients with MGUS and multiple myeloma. Exp Hematol. 2009;37:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker BA, Leone PE, Jenner MW, Li C, Gonzalez D, et al. Integration of global SNP-based mapping and expression arrays reveals key regions, mechanisms, and genes important in the pathogenesis of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108:1733–1743. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman MA, Lawrence MS, Keats JJ, Cibulskis K, Sougnez C, et al. Initial genome sequencing and analysis of multiple myeloma. Nature. 2011;471:467–472. doi: 10.1038/nature09837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egan JB, Shi CX, Tembe W, Christoforides A, Kurdoglu A, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of multiple myeloma from diagnosis to plasma cell leukemia reveals genomic initiating events, evolution, and clonal tides. Blood. 2012;120:1060–1066. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-405977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zandecki M, Facon T, Preudhomme C, Vanrumbeke M, Vachee A, et al. The retinoblastoma gene (RB-1) status in multiple myeloma: a report on 35 cases. Leuk Lymphoma. 1995;18:497–503. doi: 10.3109/10428199509059651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juge-Morineau N, Harousseau JL, Amiot M, Bataille R. The retinoblastoma susceptibility gene RB-1 in multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 1997;24:229–237. doi: 10.3109/10428199709039011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juge-Morineau N, Mellerin MP, Francois S, Rapp MJ, Harousseau JL, et al. High incidence of deletions but infrequent inactivation of the retinoblastoma gene in human myeloma cells. Br J Haematol. 1995;91:664–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb05365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burkhart DL, Sage J. Cellular mechanisms of tumour suppression by the retinoblastoma gene. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:671–682. doi: 10.1038/nrc2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Classon M, Harlow E. The retinoblastoma tumour suppressor in development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:910–917. doi: 10.1038/nrc950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacks T, Fazeli A, Schmitt EM, Bronson RT, Goodell MA, et al. Effects of an Rb mutation in the mouse. Nature. 1992;359:295–300. doi: 10.1038/359295a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee EY, Chang CY, Hu N, Wang YC, Lai CC, et al. Mice deficient for Rb are nonviable and show defects in neurogenesis and haematopoiesis. Nature. 1992;359:288–294. doi: 10.1038/359288a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vooijs M, Berns A. Developmental defects and tumor predisposition in Rb mutant mice. Oncogene. 1999;18:5293–5303. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sage J, Miller AL, Perez-Mancera PA, Wysocki JM, Jacks T. Acute mutation of retinoblastoma gene function is sufficient for cell cycle re-entry. Nature. 2003;424:223–228. doi: 10.1038/nature01764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vooijs M, van der Valk M, te Riele H, Berns A. Flp-mediated tissue-specific inactivation of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene in the mouse. Oncogene. 1998;17:1–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dannenberg JH, Schuijff L, Dekker M, van der Valk M, te Riele H. Tissue-specific tumor suppressor activity of retinoblastoma gene homologs p107 and p130. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2952–2962. doi: 10.1101/gad.322004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee MH, Williams BO, Mulligan G, Mukai S, Bronson RT, et al. Targeted disruption of p107: functional overlap between p107 and Rb. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1621–1632. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robanus-Maandag E, Dekker M, van der Valk M, Carrozza ML, Jeanny JC, et al. p107 is a suppressor of retinoblastoma development in pRb-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1599–1609. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sage J, Mulligan GJ, Attardi LD, Miller A, Chen S, et al. Targeted disruption of the three Rb-related genes leads to loss of G(1) control and immortalization. Genes Dev. 2000;14:3037–3050. doi: 10.1101/gad.843200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casola S, Cattoretti G, Uyttersprot N, Koralov SB, Seagal J, et al. Tracking germinal center B cells expressing germ-line immunoglobulin gamma1 transcripts by conditional gene targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7396–7401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602353103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rommel PC, Bosque D, Gitlin AD, Croft GF, Heintz N, et al. Fate mapping for activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) marks non-lymphoid cells during mouse development. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polager S, Ginsberg D. E2F - at the crossroads of life and death. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:528–535. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhattacharya D, Cheah MT, Franco CB, Hosen N, Pin CL, et al. Transcriptional profiling of antigen-dependent murine B cell differentiation and memory formation. J Immunol. 2007;179:6808–6819. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.