Abstract

Due to the biological and industrial importance of hypochlorous acid, the development of optical probes for HOCl has been an active research area. Hypochlorous acid and hypochlorite can oxidize electron-rich analytes with accompanying changes in molecular sensor spectroscopic profiles. Probes for such processes may monitor HOCl levels in the environment or in an organism and via bio-labeling or bioimaging techniques. This review summarizes recent developments in the area of chromogenic and fluorogenic chemosensors for HOCl.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Hypochlorous acid (HOCl) is used as a disinfectant and plays a role as an oxidant in biological processes. Industrially HOCl can be produced, for example, by the electrolysis of seawater and brine liquor.1 As a powerful oxidant, HOCl has been used as in the treatment of sewage, the sterilization of hospital laundry, the treatment of cooling water at coastal power stations, and as a bleaching agent in the paper and textile industries. The biochemistry of HOCl promotes the ability of activated phagocytes to kill a wide range of pathogens. It is generated during an oxidation reaction between chloride ions and H2O2 that is catalyzed by myeloperoxidase (MPO) secreted by activated phagocytes in the inflammatory state.2–5 Although it plays a protective role in human health, excess HOCl can cause tissue damage and diseases such as hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury, atherosclerosis, lung injury, rheumatoid and cardiovascular diseases, neuron degeneration, arthritis, and cancer.6–13 It has been reported that the concentration of HOCl in body fluids under pathological conditions can approach 200 μM. In diseased airways HOCl reaches mM levels.14

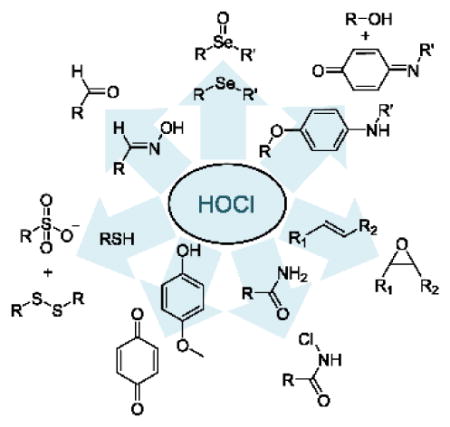

There is thus significant interest in the design of analytical methodologies that target HOCl determination. Instrumental methods include potentiometry, coulometric titration and amperometry.15–17 However, many of these methods have relatively high detection limits and require relatively tedious procedures and expensive devices. To address the challenges inherent in the in vivo monitoring of HOCl, fluorescent and/or colorimetric indicators based on unique reaction mechanisms have been recently reported by several research groups. These indicator mechanisms include p-methoxyphenol oxidation to p-benzoquinones,18–23 oxime oxidation to aldehydes,24–29 the chlorination of thioesters and amides,30–40 p-aminophenol analog oxidation,4,41–44 thioether to sulfonate and selenide to selenoxide transformations,5,45–59 the cleavage of carbon-carbon double bonds,2,60–62 and oxidative processes in metal complexes.7,63–67 This review classifies probes for HOCl based on the seven different detection mechanisms.

1. Oxidation of p-methoxyphenol to benzoquinone

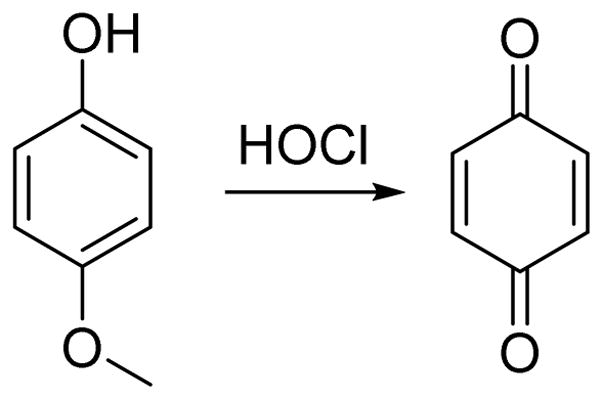

It is well-known that p-methoxyphenol can be selectively oxidized to benzoquinone by HOCl (Scheme 1). Yang and coworkers were the first to apply the specific reaction between p-methoxyphenol and HOCl towards both the detection of HOCl as well as its bioimaging.18

Scheme 1.

The oxidation of p-methoxyphenol by HOCl.

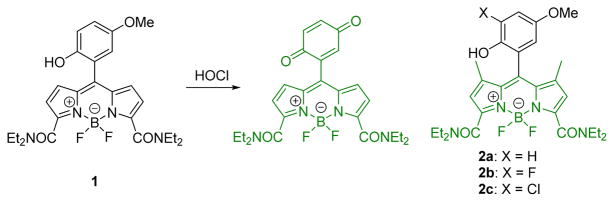

As shown in Fig. 1, HOCl oxidizes the PET-quenched BODIPY-type probe 1 to the corresponding quinine. This resulted in strong emission at 541 nm when excited at 520 over a pH range of 5–7.5. The probe was successfully employed to image the production of HOCl in live macrophage cells. The probe enabled detection of HOCl without interference from related oxidizing agents including H2O2, 1O2, •NO, O2•−, •OH, ONOO−, and ROO•. For a continuous work, the Yang group recently reported a series of second generation probes (2a, 2b, and 2c) with enhanced selectivity, sensitivity, and chemostability.19 Further, probe 2b could be used for endogenous HOCl Visualization in both RAW264.7 mouse macrophages and human THP-1 monocytic macrophages.

Fig. 1.

The detection mechanism of probe 1 towards HOCl and structures of probe 2a, 2b, and 2c.

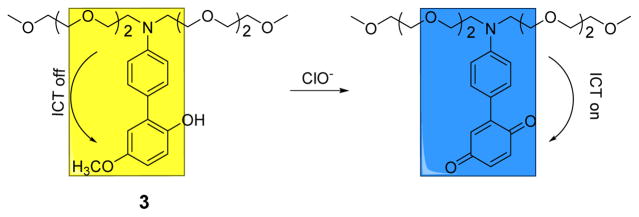

A highly selective naked-eye probe, p-methoxyphenol-substituted aniline derivative 3, for the detection of ClO− in aqueous solutions in the pH range of 5–9, was recently reported.20 Upon the addition of ClO− in PBS to 3, a decrease in the absorption band at 310 nm and formation of a new bathochromic absorption band with a maximum at 572 nm was detected. This new absorption was attributed to the oxidation of the p-methoxyphenol unit to the corresponding benzoquinone-substituted aniline which resulted in the colorless solution turning blue gradually via an ICT process (Fig. 2). The detection limit was estimated at 1.74 μM. In the presence of other reactive oxygen and nitrogen species including H2O2, 1O2, •NO, O2•−, •OH, ONOO− and ROO•, the absorption spectrum of 3 remained relatively unaltered. The presence of both anions (i.e., F−, Cl−, Br−, I−, ClO3−, ClO4−, CO32−, SO42−, PO43−, H2PO4− and OH−) and cations (i.e., Fe2+, Fe3+, Cu2+ and Zn2+) did not interfere with the visible detection of ClO−.

Fig. 2.

The reaction of probe 3 and ClO−.

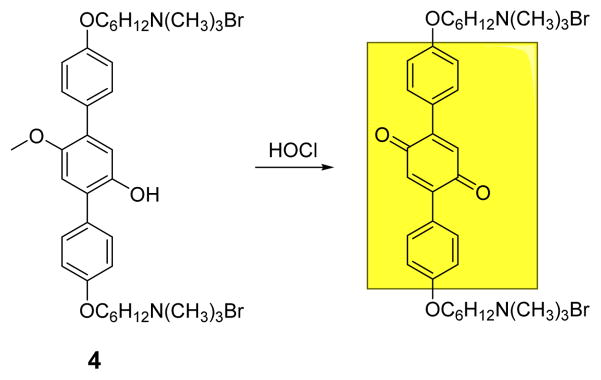

Yang and co-workers designed and synthesized a simple, water-soluble p-methoxyphenol derivative 4 that shows colorimetric and fluorimetric dual-signaling responses for HOCl in PBS buffer (0.01 M, pH 7.4) (Fig. 3).21 In the presence of ClO−, the solution color changed as a result of the shift of the original absorbance of 4 at 314 nm to 393 nm. Fluorescence emission 388 nm decreased dramatically upon increasing ClO− concentration. The observed behavior was attributed to p-methoxyphenol oxidation. The addition of other reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (H2O2, 1O2, •NO, O2•−, •OH, ONOO− and ROO•) did not induce signaling.

Fig. 3.

The reaction of probe 4 and HOCl.

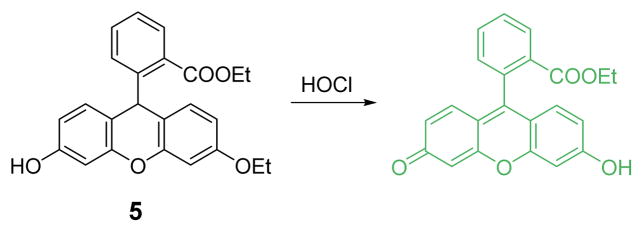

A water-soluble dihydrofluorescein-ether probe 5, was also designed on the basis of a similar HOCl-promoted oxidation (Fig. 4).22 Upon addition of HOCl a > 1000-fold fluorescence enhancement at 485 nm after 30 min in HEPES buffer (20 mM, pH 7.2) was observed. The presence of other oxidizing species showed negligible fluorescent enhancement, even at 1000 equiv. levels compared to probe concentration. The detection limit was estimated to be 6.68 nM on the basis of the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N = 3). Live cell imaging studies showed that 5 possessed excellent cell membrane permeabilty and non-cytotoxic properties.

Fig. 4.

The reaction of probe 5 and HOCl.

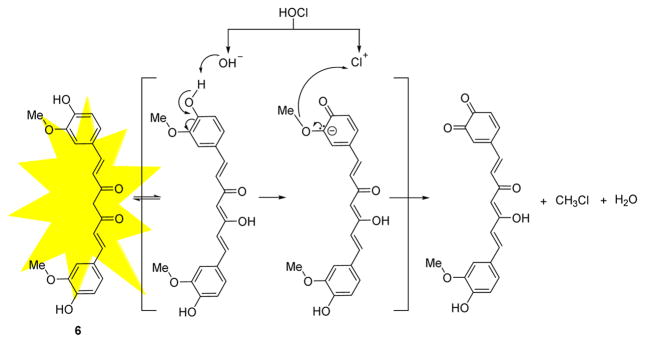

Yin and co-workers reported a curcumin-based fluorescent probe 6 for the detection of HOCl in biological systems (Fig. 5).23 When excited at 420 nm, the addition of HOCl to 6 in MeOH:HEPES (pH 7.0) 3:1 (v/v) caused a fluorescent decrease at 544 nm. Excellent selectivity for HOCl was observed compared to other oxidants. A detection limit of 0.065 μM was reported. Probe 6 functioned over the pH range of 7–11, thereby rendering it potentially useful for environmental or industrial applications. The probe was cell permeable and detected HOCl in 84 disinfectant samples.

Fig. 5.

The reaction of probe 6 and HOCl.

2. The oxidative deoximation reaction of luminescent oxime

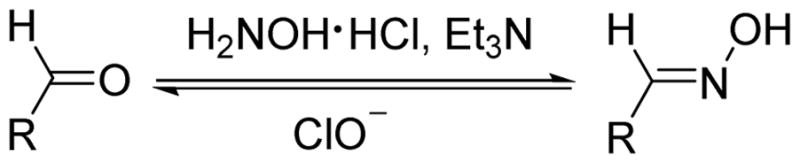

Hydroxylamines are converted to aldehydes via a deprotection reaction with ClO− under mild conditions (Scheme 2).24 There are several examples whereby fluorescence intensity has been enhanced by the removal of a C=N bond in a fluorogenic molecule via the reaction of an oxime and HOCl.27–29

Scheme 2.

The specific oxidation reaction between oximes and HOCl.

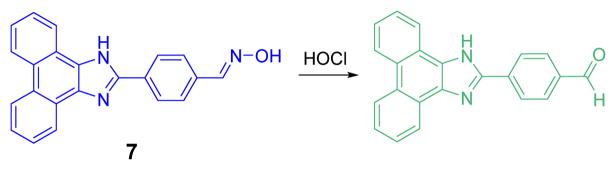

The oxime based probe 7 was first employed as a probe for HOCl by Lin (Fig. 6).24 Through an ICT process, 7 exhibits strong blue fluorescent emission at 439 nm when excited at 394 nm in phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 9.0):DMF 1:4 (v/v). When the reaction occurs, the stronger ICT of the product induces a red shift of about 70 nm. Additionally, the varying the pH in the aqueous portion from 2.5 to 10.5 showed a negligible effect on the ratiometric responses of 7 to ClO−. A wide variety of cations, anions and oxidants were tested for potential interference but did not affect the detection of HOCl.

Fig. 6.

The reaction of probe 7 and HOCl.

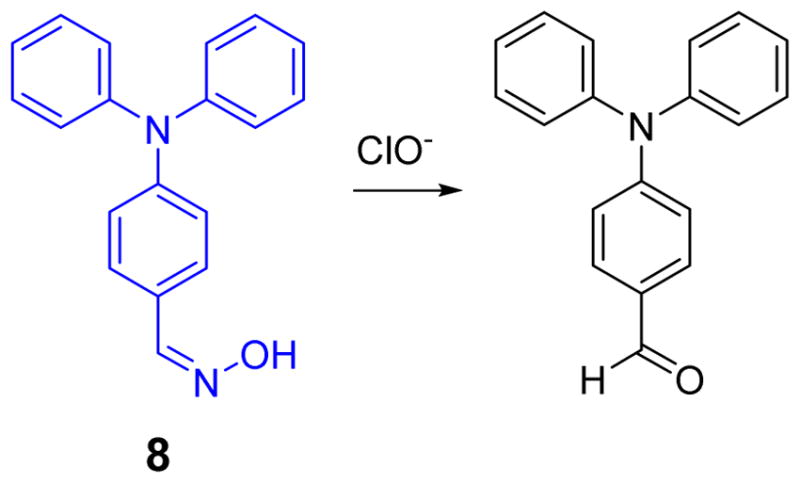

An oxime-based turn-off chemosensor 8 for HOCl was designed by the Li group (Fig. 7).25 Triphenylamine derivative 8 showed strong blue fluorescence centered at 458 nm when excited at 339 nm in phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 9):DMF 1:4 (v/v) at rt. Upon addition of HOCl, a dramatic fluorescent decrease could be visually observed by the naked eye in a room under normal lighting that quenched when the concentration of HOCl reached 200 equiv. The process completed in 3 min. A linear correlation was observed between the emission intensity and the concentration of ClO− over a range of 7 to 18 × 10−5 M. The probe functioned at pH values 8.0 and 10.0. The presence of excess levels of other analytes, including Li+, ClO4−, H2O2, Na+, NO2−, Cu2+, Cl−, OAc−, K+, ClO3−, CO32−, SO42−, Zn2+, and Mg2+ did not effect HOCl-induced signaling.

Fig. 7.

The reaction of probe 8 and ClO−.

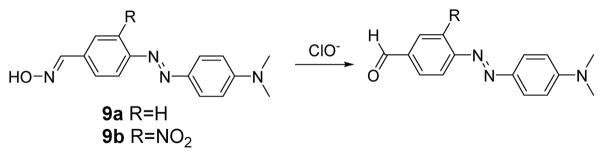

Two more oxime-based colorimetric probes for ClO− have been reported (Fig. 8).26 In solutions of 9a and 9b, the reaction caused a change in their UV-vis spectra via ICT. 9a shows maximum absorption at 453 nm with a molar extinction coefficient (ε) of 2.1 × 104 L mol−1 cm−1 in phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 9.2):DMF 4:1, (v/v) at rt. Upon the introduction of ClO− (32 equiv.) to the solution of 9a (10 μM), the absorption maximum of 9a shifts from 453 to 475 nm. Because of the presence of the nitro group in 9b, the absorption spectrum of 9b shows a bathochromic-shift band centered at 489 nm. Upon addition of ClO−, the absorption of 9b, centered at 489 nm, gradually decreased with concomitant formation of a new peak at 510 nm, corresponding to a color change from orange to pink, which was clearly visible. The detection limit of 9b for ClO− was 2 μM. Similar to other HOCl probes, 9a and 9b show high selectivity for ClO− over other cations, anions and oxidants.

Fig. 8.

The reaction of probes 9a and 9b with ClO−.

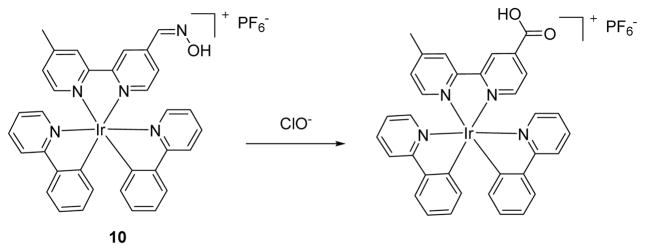

A novel iridium (III) complex of an oximated 2,2′-bipyridine based ClO− probe was reported by the Chen group (see Fig. 9).27 Complex 10 is almost non-emissive due to C=N–OH isomerization as a predominant non-radiative decay process in the excited state. Through the selective oxidation of the oxime to an aldehyde or carboxylic acid, the addition of ClO− caused strong fluorescent emission at 578 nm when excited at 346 nm in DMF:HEPES (50 mM, pH 7.2) 4:1 (v/v). DFT computational studies revealed that the produced complex [Ir(ppy)2(L2)](PF6) exhibits bright orange-yellow luminescence originating from [5d(Ir)→π*(bpy)] 3MLCT and [π(ppy) →π*(bpy)] 3LLCT triplet excited states, which were comparable to those of the experimental data. The selectivity of probe 10 toward ClO− was shown to be unaffected by the presence of H2O2, •NO, O2•−, •OH, ROO• and various metal ions. In addition, the use of test strips containing 10 showed highly promising sensitivity to ClO−.

Fig. 9.

The reaction of probe 10 and ClO−.

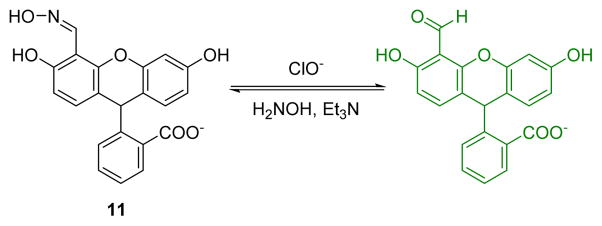

A “turn-on” fluorescent probe (11) for HOCl based on a fluorescein-oxime architecture was synthesized (Fig. 10).28 Along with the specific oxidation reaction of the oxime and HOCl, reaction induced distinct fluorescent emission at 530 nm when excited at 454 nm in DMSO:HEPES (10 mM, pH 7.05) 1:9 (v/v). The solution color changes from colorless to light yellow which could be readily visualized. The emission at 530 nm increased gradually upon increasing the concentration of ClO−. The detection limit was 5 μM. Selectivity studies showed that AcO−, NO2−, NO3−, ClO3−, F−, ClO4−, HCO3−, PO43−, Cl−, IO3−, HPO42−, Br−, HSO3−, HSO4−, I−, S2O32−, SCN−, and H2O2 did not interfere with ClO− analysis. Probe 11 could thus be potentially used in sensing and cellular imaging.

Fig. 10.

The reaction of probe 11 and ClO−.

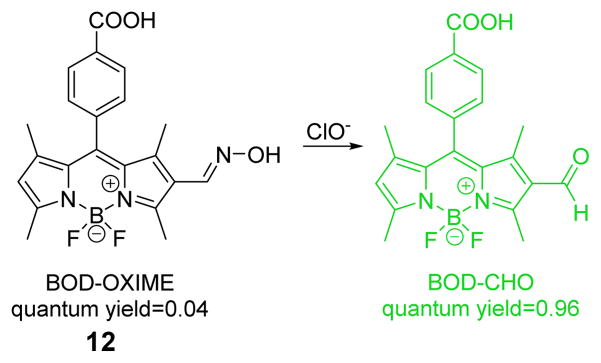

A BODIPY-based turn-on fluorescent probe 12 was designed and synthesized for the fluorescence detection of ClO− in aqueous media (Fig. 11).29 Probe 12 exhibits poor fluorescence. Upon addition of HOCl, a band appears at 525 nm when excited at 500 nm in PBS buffer (0.1 M pH 7.4). The fluorescence intensity versus ClO− concentration plot is linear over a range from 0 to 6 mM. The detection limit was determined to be 17.7 nM. Other potentially competing reactive oxygen species (ROS) or reactive nitrogen species (RNS) did not affect the detection of HOCl. Probe 12 is reported to be fast-responding, highly sensitive, photostable and water soluble. Its utility was demonstrated in imaging both exogenous and endogenous ClO− in live cells.

Fig. 11.

The reaction of probe 12 and ClO−.

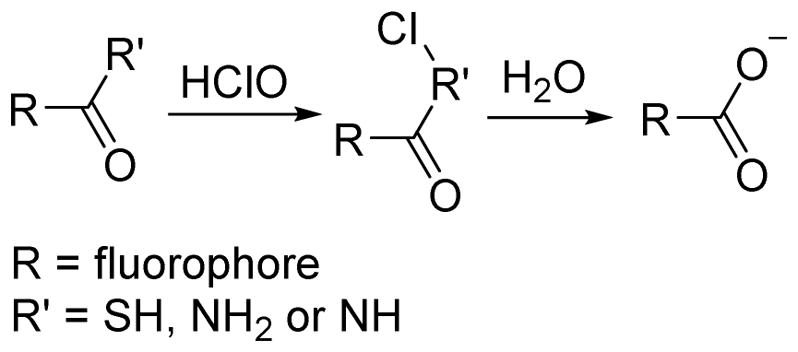

3. The chlorination of thioesters and amides by HOCl

As a strong oxidant, HOCl can react with thioesters and amides via chlorination reactions to produce –S-Cl and –N-Cl species as intermediates (Scheme 3). These intermediates lead to carboxylates in aqueous solution. When a hydrazide group is a component of the sensing system, the chlorination reaction converts the hydrazine moiety to azo. The design of probes containing fluorophores with the aforementioned functional groups has led to several unique HOCl indicators.

Scheme 3.

The specific chlorination reaction between thiols or amides and HOCl.

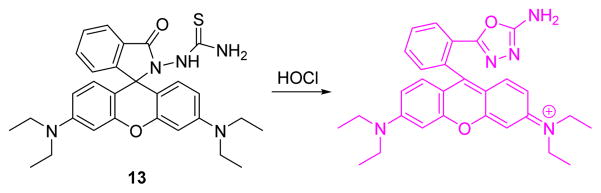

Loo, Zhang and co-workers reported a novel water-soluble organic-nano up-conversion luminescence (UCL) detection system for HOCl based on a rhodamine-modified thiosemicarbazide (13, Fig. 12).30 Upon reaction of 13 with HOCl, the green UCL emission intensity gradually decreased as near-infrared (NIR) emission exhibited no change, a desirable property for ratiometric UCL detection. The nanoparticles were successfully used for ratiometric UCL visualization of HOCl that was released by MPO-mediated peroxidation of chloride ions in living cells.

Fig. 12.

The reaction of probe 13 with HOCl.

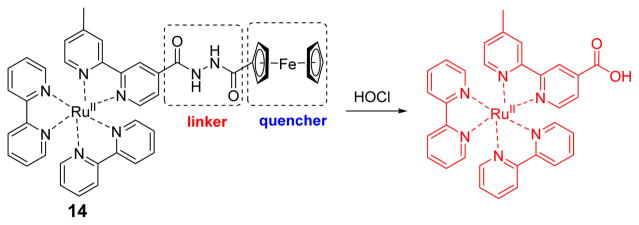

Very recently the Yuan group synthesized a ruthenium-ferrocene (RuFc) multisignal chemosensor for the highly selective detection of lysosomal HOCl (Fig. 13).31 Probe 14 was weakly luminescent because MLCT (metal-to-ligand charge transfer) state was hindered by an efficient PET (photoinduced electron transfer) process from the Fc moiety to the Ru(II) center. The cleavage of the Fc moiety occurred via a HOCl-induced oxidation of a hydrazide-derived linker, resulting in elimination of PET, accompanied by striking photoluminescence (PL) and electrochemiluminescence (ECL) enhancements. Probe 14 exhibited low cytotoxicity and was used for the quantitative detection of HOCl in live cells by confocal microscopy imaging and flow cytometry analysis. The imaging of endogenous HOCl generated in live macrophage cells during the stimulation was achieved. HOCl was visualized in laboratory model animals, Daphnia magna and zebrafish.

Fig. 13.

The reaction of probe 14 and HOCl.

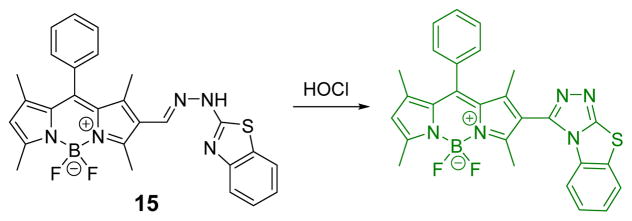

Wu and co-workers reported a BODIPY-based fluorescent probe for the detection of HOCl based on a hypochlorous acid-promoted oxidative intramolecular cyclization (Fig. 14).32 The reaction was accompanied by a 41-fold increase in the fluorescent quantum yield (0.004 to 0.164) and fluorescence intensity was linear in the HOCl concentration range of 1–8 μM with a detection limit of 2.4 nM (S/N = 3). Confocal fluorescence microscopy imaging using RAW264.7 cells showed that probe 15 was effective in living cells.

Fig. 14.

The reaction of probe 15 and HOCl.

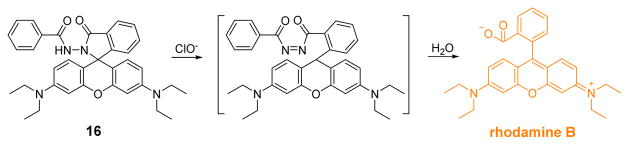

The Ma group used an N-benzoyl rhodamine B–hydrazide 16 (Fig. 15) for HOCl detection.33 Probe 16 has no absorption in the visible region in its closed spirolactam form. Upon reaction with ClO−, however, a new absorption band at 556 nm appeared as the solution color changed from colorless to pink. The reaction thus restored the rhodamine B color as a function of increasing ClO− concentration. Similarly, rhodamine fluorescence (λem = 578 nm) was observed in Na2B4O7 buffer (0.03 M, pH 12):THF 7:3 (v/v). The turn-on probe exhibited ΔF = 52.69C − 29.83 (n = 10, γ = 0.9992) and a detection limit of 27 nM (S/N = 3). Further selectivity experiments displayed high selectivity of probe 16 to ClO− over other species including Ca2+, Cu2+, Fe3+, Fe2+, Hg2+, K+, Mg2+, Mn2+, Ni2+, Pb2+, Zn2+, MnO4−, H2O2, Cl−, ClO3−, SO42−, NO3−, PO43−, and SiO32−.

Fig. 15.

The reaction of probe 16 and HOCl.

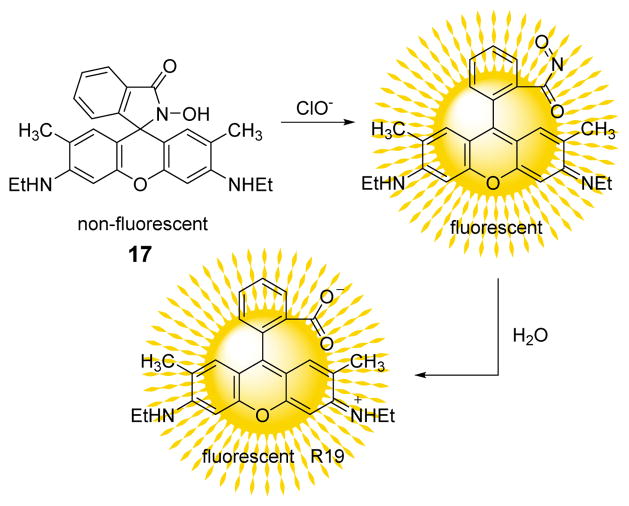

A new fluorescent probe 17 for HOCl was synthesized from rhodamine 6G based on its chlorination reaction (Fig. 16).34 Fluorescence intensity changes of probe 17 towards HOCl (5.0 equiv.) and other ROS (100 equiv. of H2O2, •NO, O2•−, •OH, ROO•) in PBS buffer (pH 7.4):DMF 999:1 (v/v) were measured to evaluate the selectivity of 17. Only HOCl enhanced the fluorescence intensity at 547 nm when excited at 500 nm to a significant extent. The other ROS studied did not interfere. In addition to the fluorescent changes, the solution changed from colorless to pink as readily observed by visual inspection. Fluorescence titration of 17 with HOCl afforded a limit of detection of 25 nM. In cellular experiments, probe 17 showed favorable membrane permeability and was used in the bioimaging of HOCl.

Fig. 16.

The reaction of probe 17 and ClO−.

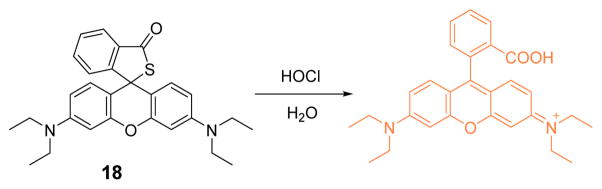

Subsequently, a rhodamine B thiospirolactone-based probe 18 was successfully developed as a highly sensitive and selective fluorescent probe for HOCl by Xu’s team (Fig. 17).35 In this investigation, both the absorption and fluorescence spectra of the probe, as a function of varying concentration of NaClO, were measured in phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4):DMSO 99:1 (v/v). The probe solution without added NaClO was colorless and non-fluorescent, due to the spiro-ring structure. Dramatic formation of a pink solution color observed upon addition of NaClO, accompanied by significant enhancements in absorption (561 nm) and fluorescence (579 nm, excited at 525 nm). The probe afforded a linear correlation between the emission intensity and NaClO (0.5–7.0 μM) concentration, with a detection limit of 0.3 μM. Probe 18 overall exhibited high selectivity, function over a wide pH range, and favorable photostability and toxicity profiles, thereby showing great potential for bioimaging and environmental detection.

Fig. 17.

The reaction of probe 18 and HOCl.

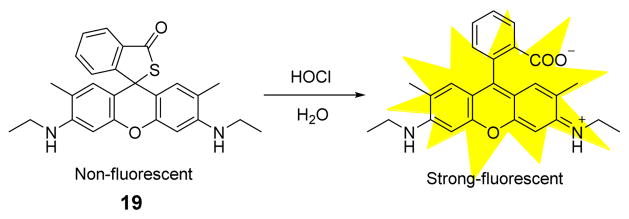

An analogous fluorescent probe 19 for HOCl based on rhodamine 19 was later reported by the Yoon group (Fig. 18).36 Initially, treatment of 19 with 1 equiv. HOCl resulted in a significant fluorescence increase at 547 nm in phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 5.5):CH3CN 99:1 (v/v). Probe 19 displayed high selectivity toward HOCl over excess (20 equiv.) other ROS, such as H2O2, 1O2, •NO, O2•−, •OH, ONOO− and ROO•. Fluorescent titration experiments demonstrated that the fluorescence intensity of 19 and HOCl concentration had a linear relationship over a HOCl concentration range of 0–12 μM. Impressively, the high specificity and sensitivity of 19 as well as its unique activity under relatively acidic conditions rendered it useful towards visualizing phagosomal and mucosal HOCl production in a variety of cellular contexts. This successful application of HOCl detection and imaging in live cells and tissues of an animal model should inspire investigations of the role of HOCl in a wide variety of biological processes.

Fig. 18.

The reaction of probe 19 and HOCl.

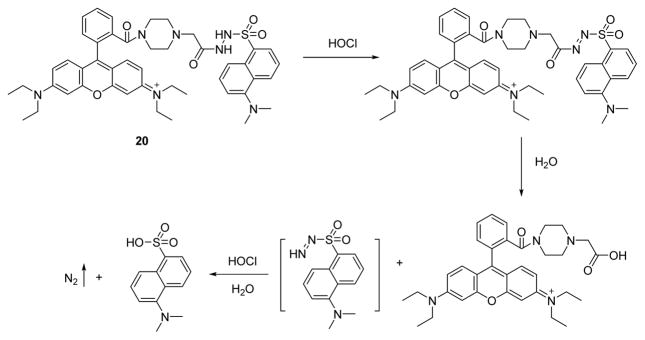

A water-soluble fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) probe 20 for HOCl was designed, synthesized and characterized (Fig. 19).37 Probe 20, connects a FRET donor (dansyl, DNS) and FRET acceptor (rhodamine, RBPH) via a HOCl-cleavable active bond. It was found to react with HOCl and afford a change of fluorescence at pH = 7.4. Through intramolecular FRET, the fluorescence of the DNS unit of 20 is quenched, and only the fluorescence (λem = 585 nm) of the RBPH unit is observed (Φ = 0.07 in H2O). When HOCl was added to the probe solution, the DNS fluorescence (λem = 501 nm) appeared and, surprisingly, the fluorescence intensity of the RBPH unit also increased (Φ = 0.19 in H2O). In the titration experiment, the plot of fluorescence intensities of 20 at 501 nm showed a linear relationship to the concentration of HOCl over a 2–10 μM range, with a regression equation of ΔF = 0.704C + 0.097 and a linear correlation coefficient of 0.998. The detection limit was 80 nM (S/N = 3). Based on its solubility and sensitivity, probe 20 was successfully used in the fluorescence imaging of HOCl in HeLa cells.

Fig. 19.

The reaction of probe 20 and HOCl.

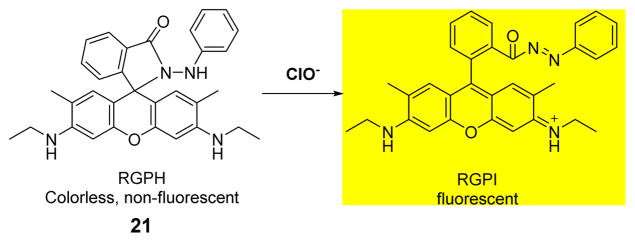

Another rhodamine 6G-based fluorescent probe 21 for the detection of HOCl, functioning over a wide pH range, was reported by the Zeng group (Fig. 20).38 Upon addition of various anions and metal cations, such as Cl−, ClO4−, NO2−, NO3−, SO42−, ClO−, Ca2+, K+, Mg2+, Pb2+, Ni2+, Zn2+, Fe3+, Cu2+, Hg2+ and H2O2 to a solution of 21 in H2O, only HOCl induced a new absorption band centered at 521 nm. The fluorescence titration profiles of solutions of 21 with added NaClO were measured upon excitation at 505 nm and emission at 548 nm in H2O. Addition of HOCl to 21 induced fluorescent enhancement at 548 nm over a wide pH range (pH = 6–12). In addition, the oxidation product of 21 was stable over a wide pH range. These findings suggest that artificial buffer solutions are not required for the detection of ClO−. Moreover, probe 21 could be used in the detection of ClO− in both running tap water and earth-soaked water.

Fig. 20.

The reaction of probe 21 and ClO−.

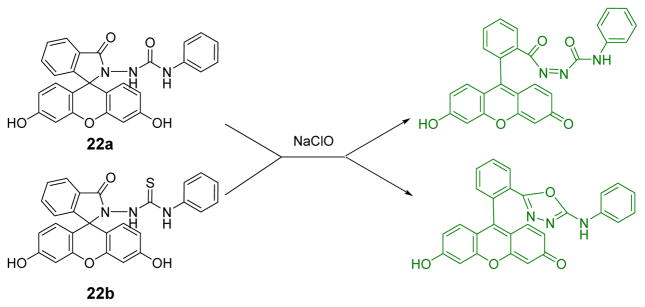

Based on the specific chlorination reaction, two fluorescein-based probes, 22a and 22b (Fig. 21), were designed for the detection of HOCl.39 Similar to the rhodamine derivatives, their chlorination products exhibited excellent photophysical properties via the ring-opened structure. The addition of HOCl to 22a and 22b (pH = 7.4) induced strong green fluorescence emission at 528 nm for 22a and at 527 nm for 22b with excitation at 480 nm. In contrast, other species such as NaCl, KCl, CaCl2, Mg(ClO4)2, Fe(ClO4)2, Zn(ClO4)2, Cu(ClO4)2, Hg(ClO4)2 and H2O2 did not induce any fluorescent enhancement for 22a. For 22b; however, a fluorescence enhancement at 530 nm was also observed in the presence of Hg2+, though other analytes did not interfere.

Fig. 21.

The reaction of probe 22 and HOCl.

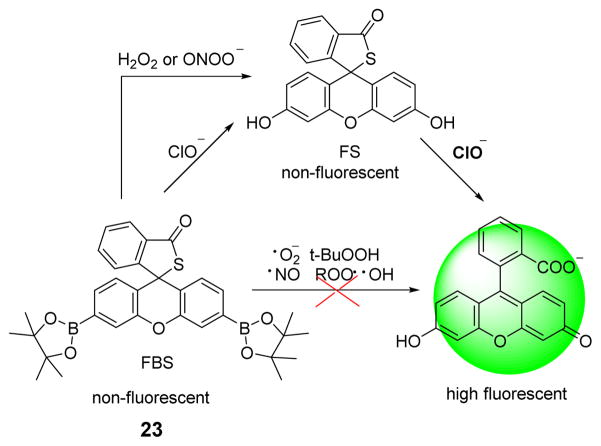

Recently, Yoon et al. reported a “dual-lock” fluorescein based HOCl probe 23 (Fig. 22).40 In this investigation, both FBS (23) and FS were studied for their potential fluorescent responses to various ROS/RNS. Only HOCl could both react with the arylboronates as well as hydrolyze the thiolactone to afford the fluorescein. Probe 23 was successfully applied to the in vivo imaging of physiological HOCl production in the mucosa of live animal models.

Fig. 22.

The reaction of probe 23 and ClO−.

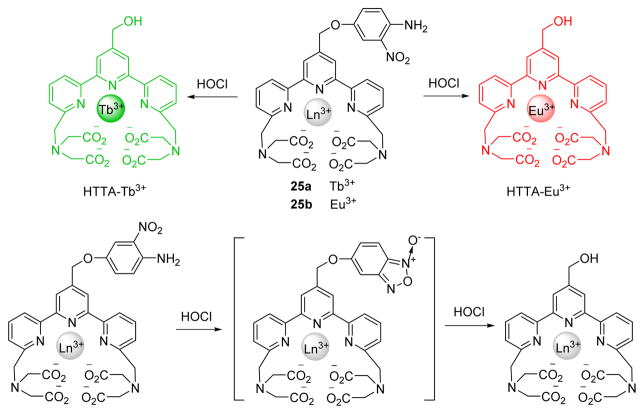

4. Oxidation reactions of p-aminophenol analogues

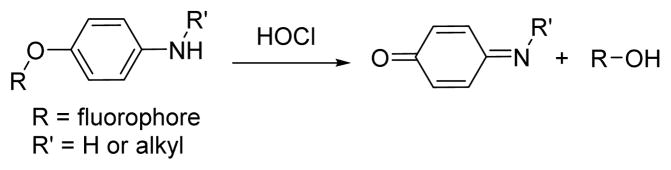

Like p-methoxyphenol, the p-aminophenyl aryl ether moiety reacts expeditiously with ROS, and preferably with ClO−, to give 1,4-benzoquinone imines via an ipso-substitution mechanism (Scheme 4).41 The utility of this moiety for designing HOCl-selective indicators is described in the following examples.

Scheme 4.

The reaction of p-aminophenol analogues and HOCl.

The Libby group designed and synthesized sulfonaphthoaminophenyl fluorescein 24 as a HOCl probe based on the reaction of the p-aminophenyl aryl ether moiety with HOCl (Fig. 23).4 Upon addition of HOCl to a solution of 24 (pH 7.4), a strong fluorescence signal was generated at 676 nm upon excitation at 614 nm. Other reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, including H2O2, •NO, O2•−, •OH, and ROO•, did not interfere with the detection of HOCl at concentrations up to 10 equiv. The in vivo imaging of HOCl, produced by neutrophils in experimental murine peritonitis and MPO expressing cells in human atherosclerotic arteries, was successfully achieved via probe 24. Probe 24 may thus embody provide a valuable non-invasive molecular imaging tool for implicating HOCl and MPO in the damage of inflamed tissues.

Fig. 23.

The reaction of probe 24 and HOCl.

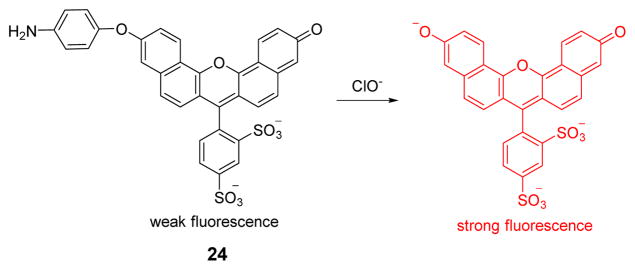

Two lanthanide complex-based luminescent probes, 25a and 25b (Fig. 24), were designed and synthesized for highly sensitive and selective time-gated luminescence detection of HOCl in aqueous media.42 The probes were nearly non-luminescent due to the PET interaction between the 4-amino-3-nitrophenyl moiety and the terpyridine-Ln3+ moiety, which quenched the lanthanide luminescence. Upon addition of HOCl, the 4-amino-3-nitrophenyl moiety was rapidly cleaved from the probe complexes, which afforded strongly luminescent lanthanide complexes HTTA-Eu3+ and HTTA-Tb3+, exhibiting luminescence enhancements at 610 nm and 540 nm respectively.

Fig. 24.

Top: the reaction of probe 25 and HOCl. Bottom: proposed detection mechanism of HOCl.

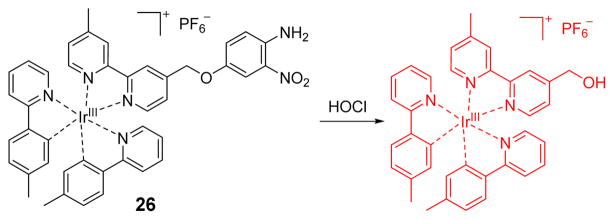

Nabeshima and Lu used the HOCl-promoted cleavage of the PET quenching 4-amino-3-nitrophenyloxy moiety of a weakly emissive iridium complex (26) to afford a highly luminescent complex that is highly selective for HOCl and was shown to successfully image HOCl in HeLa cells (Fig. 25).43

Fig. 25.

The reaction of probe 26 and HOCl.

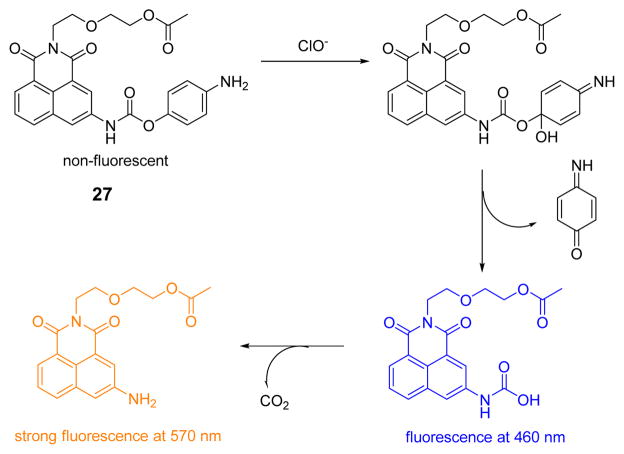

The Qian group designed and synthesized the highly water soluble fluorescence probe 27 (Fig. 26).44 With no fluorescence responses over a pH range from 6.5 to 11.0, probe 27 is suitable for applications under physiological conditions. Upon addition of ClO−, 27 showed a dual-channel emission at 460 nm and 570 nm, with excitation at 340 nm in phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4):DMF 99:1 (v/v). In contrast, OONO− led to a single-channel enhancement at 460 nm only and other ROS/RNS induced no spectral changes. As 27 can distinguish ClO− from ROS/RNS via its dual-channel signal, it was successfully used to image ClO− in live HeLa cells.

Fig. 26.

The reaction of probe 27 and ClO−.

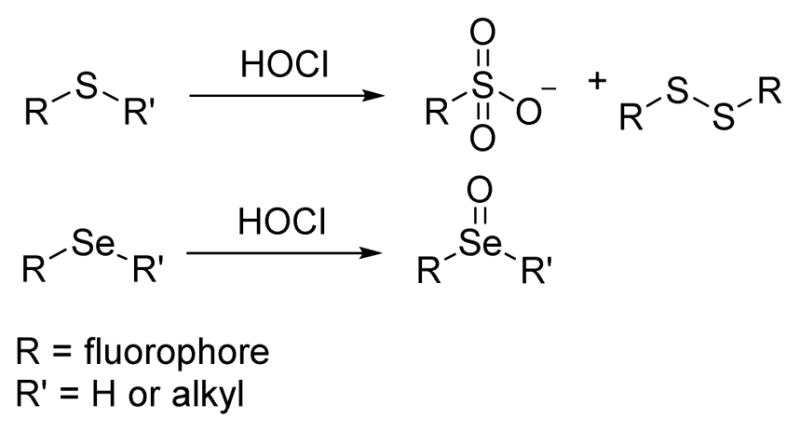

5. Thioether to sulfonate and selenide to selenoxide

Thioethers and selenides are electron donating groups that are easily oxidized by HOCl to produce sulphonates and selenoxides, which are strong electron withdrawing groups (Scheme 5). The process enables thioether- or selenide-containing probes to display useful signal changes either in their fluorescence or UV-vis spectra upon reacting with HOCl.

Scheme 5.

The oxidation reaction between thioethers, selenides and HOCl.

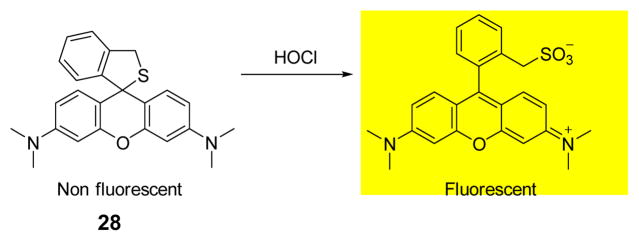

On the basis of the specific oxidation reactions, Nagano and coworkers developed a novel fluorescence probe selective for HOCl. Their strategy involved tuning the nucleophile affecting the spirocyclization of tetramethylrhodamine derivatives (Fig. 27), resulting in the creation of thioether 28.45 Upon addition of HOCl, 28 shows rapid and quantitative emission at 575 nm at pH in phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4):DMF 999:1 (v/v). Additionally, 28 displayed excellent stability in the presence of various abundant ROS generated in organisms under physiological conditions. With excellent properties at varying pH, including high photo- and oxidative stability, 28 has potential as a useful fluorescence probe for biological phenomena, such as phagocytosis.

Fig. 27.

The reaction of probe 28 and HOCl.

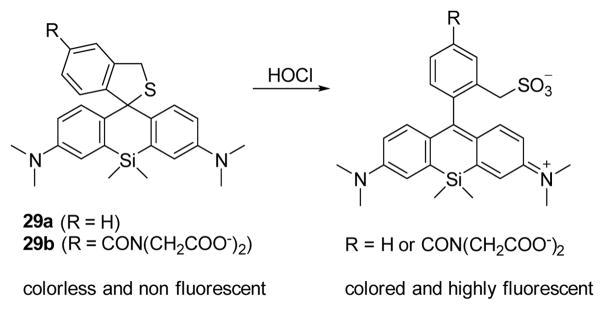

Motivated by the aforementioned results, Nagano’s team modified probe 28 in the synthesis of two Si-rhodamine far red emitting fluorescent probes 29a and 29b (Fig. 28).5 For both 29a and 29b, the absorption and maxima were close to 650 nm. Upon the addition of various ROS, only HOCl promoted emission at 670 nm (pH 7.4, 0.1% DMF), with good sensitivity. Furthermore, cellular and whole animal experiments suggested that the use of 29 was applicable to in vitro and in vivo imaging.

Fig. 28.

The reaction of probe 29 and HOCl.

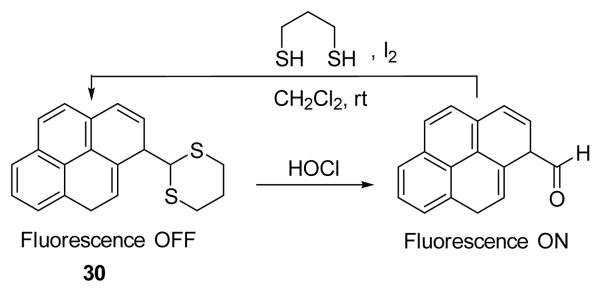

The Chang group employed a dithiolane-protected pyrene-aldehyde, as HOCl probe 30 (Fig. 29), which displayed both colorimetric and turn-on fluorescent responses.46 The UV-vis spectrum of 30 showed strong absorption bands at 315, 329, and 345 nm in 50% aqueous CH3CN. Upon treatment of 30 with 10 equiv. HOCl, the dithiolane group was removed, and new absorption bands at 361 and 395 nm appeared along with strong emission at 457 nm. Hg2+ could induce the same dithiolane deprotection as HOCl, which could be readily circumvented by employing a Chelex-100 resin.

Fig. 29.

The reaction of probe 30 and HOCl.

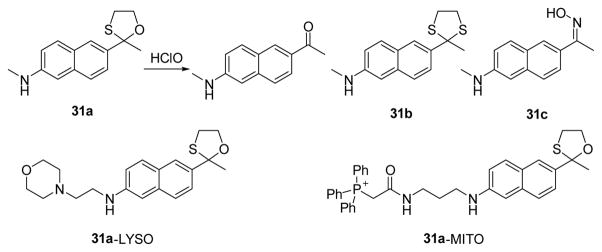

The Chang group recently incorporated the dithiolane strategy to create a series of two-photon fluorescent “turn-on” HOCl probes, including mitochondria- and lysosome-targeting derivatives, which imaged intracellular HOCl in live cell and inflamed mouse models (Fig. 30).47

Fig. 30.

Structures of the two-photon probes and the proposed detection mechanism.

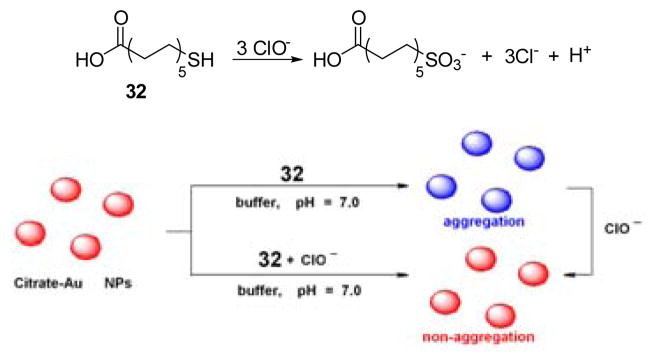

Gold nanoparticles (Au NPs) are widely used as ligating atoms in coordination and nanochemistry, and readily interact with thiols to afford colorimetric responses. A sulfydryl ligand can be oxidized by ClO− to a sulfonate, thereby desorbing the ligand. Probe 32 (Fig. 31) was designed as a colorimetric probe based on this process.48 Upon the addition of ClO−, the UV-vis absorption of Au NPs-32 at 527 nm decreased gradually as a new peak at 680 nm increased, as the solution color changed from blue to red. Moreover, several environmentally relevant anions and cations including Cl−, NO3−, SO42−, CO32−, Ca2+, Mg2+, Fe3+, Al3+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ were evaluated as possible interferents in ClO− detection. Metal cations at < 0.1 mM levels and all anions studied did not affect the HOCl detection process. Tap water experiments demostrated the applicability of probe 32 for the detection of ClO− in real-world environmental samples.

Fig. 31.

Top: the reaction of probe 32 and ClO−. Bottom: proposed detection mechanism.

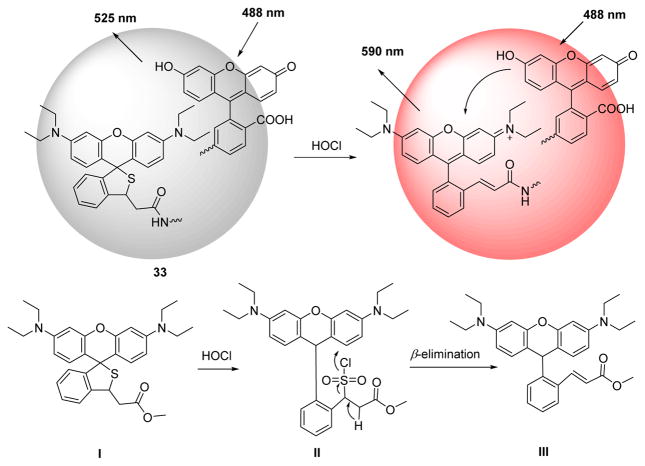

A novel silica nanoparticle probe (33) comprising FITC (donor dye) and a non-fluorescent chemodosimeter rhodamine (acceptor dye) was designed and synthesized for HOCl detection via a FRET mechanism (Fig. 32).49 Triggered by HOCl, as shown in Fig. 32, the rhodamine moiety “I” became fluorescent via a tandem oxidation and β-elimination to produce “III”. Via the FRET interaction between the fluorescein donor and the newly formed rhodamine acceptor, the ratio of the fluorescence intensities (I586 nm/I526 nm) increased significantly, enabling determination of HOCl concentration. The nano dosimeter was used for ratiometric reporting of HOCl levels in lysosomes in live cells. It functions over a wide pH range and appears to be relatively non-cytotoxic.

Fig. 32.

Top: FRET-based ratiometric imaging of HOCl by probe 33. Bottom: proposed oxidation mechanism.

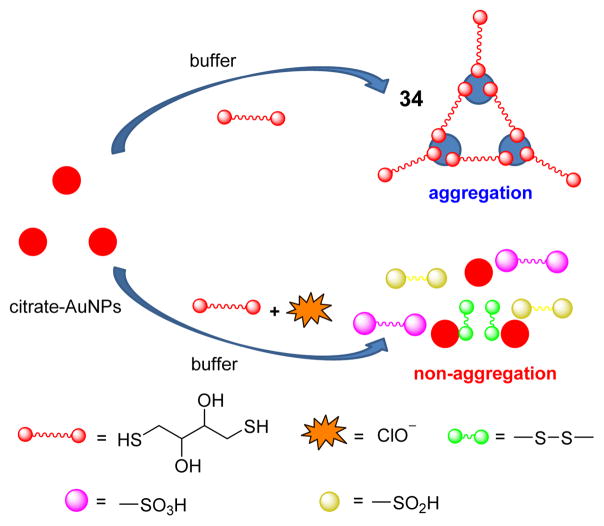

A dithiothreitol fabricated gold nanoparticle (AuNP) probe 34 was developed for the facile colorimetric detection of ClO−.50 Owing to the strong covalent S-Au bond, dithiothreitol causes AuNPs to aggregate resulting in a color change from red to blue (Fig. 33). In the presence of ClO−, however, the thiol groups are oxidized, reforming the red solution. Using this colorimetric method, 2 μM of ClO− was readily seen by visual inspection within 5 min. The method was successfully applied to ClO− determination in water samples.

Fig. 33.

Proposed detection mechanism of ClO− detection using an AuNPs-dithiothreitol system.

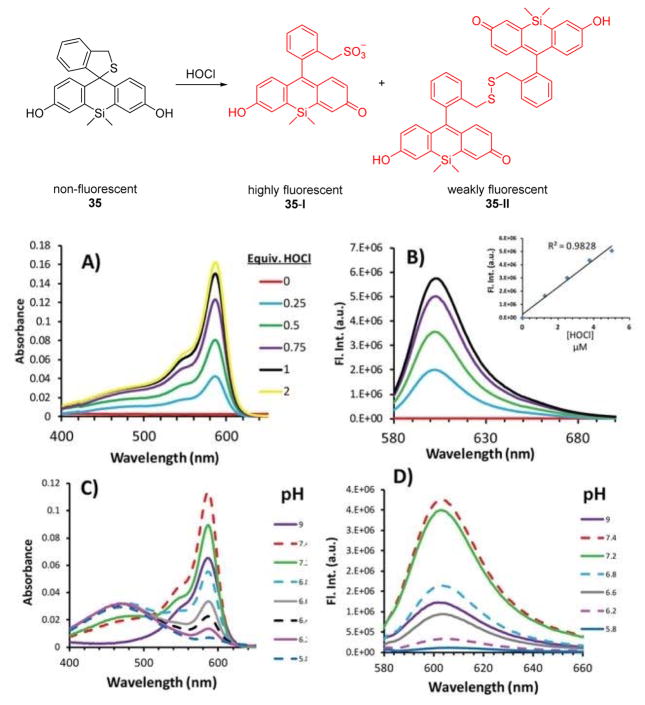

A fascinating Si-fluorescein based fluorescent probe 35 was synthesized by the McCarroll group (Fig. 34).51 Through the specific oxidation reaction of 35 and 1 equiv. HOCl, two open-form Si-fluorescein analogues 35-I and 35-II were produced. As shown in Fig. 34, in the absence of HOCl, the solutions are colorless and non-fluorescent. The addition of HOCl resulted in a new peak at 586 nm in the UV-vis spectrum in PBS (pH 7.4):DMF 199:1 (v/v) (Fig. 34, A). Excitation at this wavelength results in a strong fluorescence band centered at 606 nm (Fig. 34, B). However, both the absorption and fluorescence responses of the two products were pH dependent. Specifically, the λ586 band began to decrease, while a new relatively broad band at 475 nm increased as the pH of the buffer solution decreased (Fig. 34, C). The corresponding fluorescence spectra of these solutions show that the probe’s fluorescence intensity decreases under increasingly acidic conditions (Fig. 34, D). The fluorescence and UV-vis intensities and the ratio between the λ586 and the λ475 bands could be used to indicate the concentration of HOCl and the pH of the solution simultaneously. An excess amount of HOCl (around 5 equiv.) causes chlorination and further induces a red shift. This feature increased the detection range to 0–80 equiv. of HOCl.

Fig. 34.

Top: reaction of 35 with HOCl. Bottom: (A, C) absorption spectra and (B, D) emission spectra of 35 with HOCl in different pH buffer solutions (A, B, pH = 7.4). Reprinted with permission from J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2013, 135, 13365–13370. Copyright 2013, American Chemical Society.

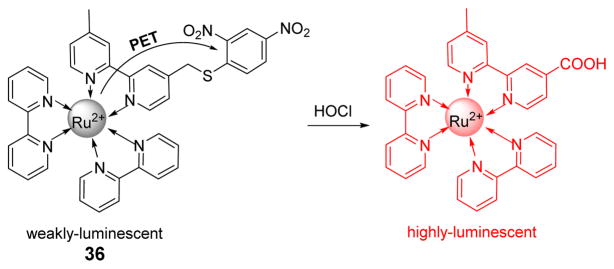

A novel Ru (II) complex, 36, was designed and synthesized as a highly sensitive and selective luminescence probe for the recognition and detection of HOCl in living cells by exploiting a “signaling moiety-recognition linker quencher” sandwich approach (Fig. 35).52 Owing to the effective PET from the Ru (II) center to the electron acceptor, 2,4-dinitrophenyl, the probe itself was non-fluorescent. In aqueous media, HOCl triggered the oxidation reaction to cleave the 2,4-dinitrophenyl moiety from 36, resulting in the formation of a highly luminescent bipyridine-Ru(II) complex derivative, accompanied by a 190-fold luminescence enhancement at 626 nm with excitation at 450 nm. Cell imaging results demonstrated that 36 was membrane permeable, and could be applied to visualizing the exogenous/endogenous HOCl molecules in living cell samples.

Fig. 35.

The reaction of probe 36 and HOCl.

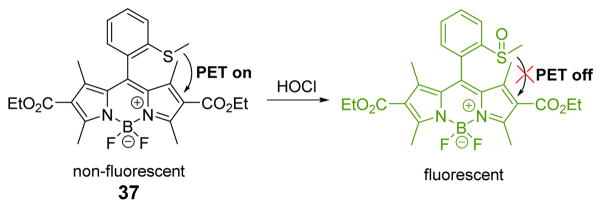

The Wu group developed a boron dipyrromethene (BODIPY)-based fluorimetric probe, 37, for the highly sensitive and selective detection of HOCl (Fig. 36).53 Confirmed by 1H, 13C NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry, the methyl phenyl sulfide moiety of 37 was oxidized by HOCl to produce sulfoxide, which eliminated the electron donor and further interdicted the PET process, accompanied by a 160-fold increase in the fluorescent emission at 516 nm with excitation at 505 nm in PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.4):CH3CN 99:1 (v/v). The fluorescence intensity of HOCl and 37 showed good linearity in the HOCl concentration range 1–10 μM. A detection limit of 23.7 nM (S/N = 3) was determined. In addition, confocal fluorescence microscopy imaging of RAW264.7 macrophages demonstrates that 37 could be an efficient optical detector of HOCl in living cells.

Fig. 36.

The reaction of probe 37 and HOCl.

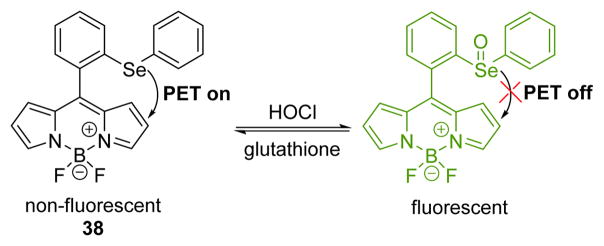

Another BODIPY-based fluorescent probe 38, bearing an organoselenium group, was synthesized for HOCl detection by the Wu group (Fig. 37).54 Compound 38 was oxidized to the selenoxide by HOCl, as confirmed by 77Se NMR and MS spectra. Probe 38 displayed weak fluorescence with a quantum yield of Φ = 0.005. Upon the addition of HOCl, the strong fluorescence of BODIPY centered at 526 nm was restored with a quantum yield of Φ = 0.690 with excitation at 510 nm in PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.4):CH3CN 99:1 (v/v). Probe 38 exhibited high selectivity and sensitivity toward HOCl over other ROS and RNS in aqueous solution. Furthermore, the detection limit was as low as 7.98 nM. Importantly, 38 showed good cell membrane permeability and could be successfully applied to image endogenous HOCl in living cells.

Fig. 37.

The reaction of probe 38 and HOCl.

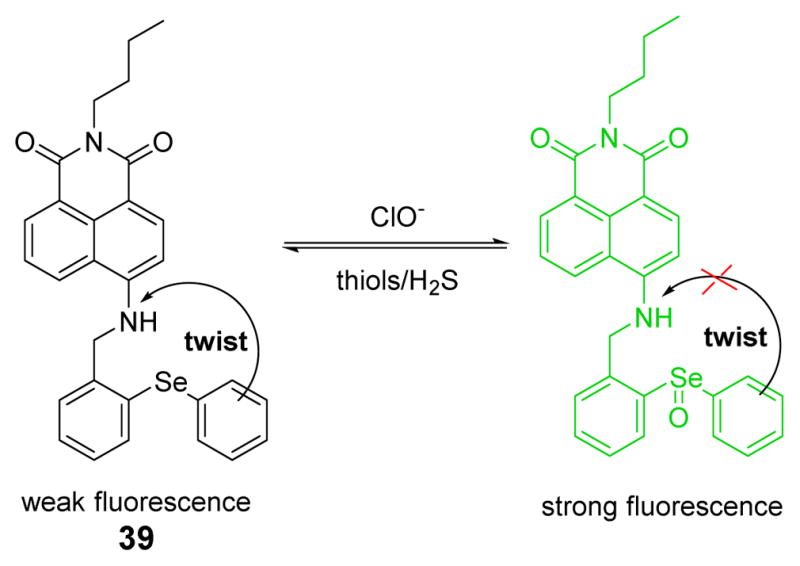

A reversible fluorescent probe 39, which connected 1,8-naphthalimide as a signal transducer and diphenyl-selenide as the reaction site, was synthesized and characterized (Fig. 38).55 A proposed PET process was validated by time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) calculations. In addition, the influence of viscosity and temperature demonstrated that there was an excited state configuration twist process, which would lead to fluorescence quenching in 39, but not in the selenoxide product. The addition of HOCl caused strong fluorescent emission at 523 nm in phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4). In the inverse process, the addition of thiols could cause a decrease of the fluorescence intensity via reduction of selenoxide. Importantly, using confocal fluorescence microscopy, 39 enabled visualization of HOCl and reducing repair in live cells and live mice in situ.

Fig. 38.

The reaction of probe 39 and HOCl.

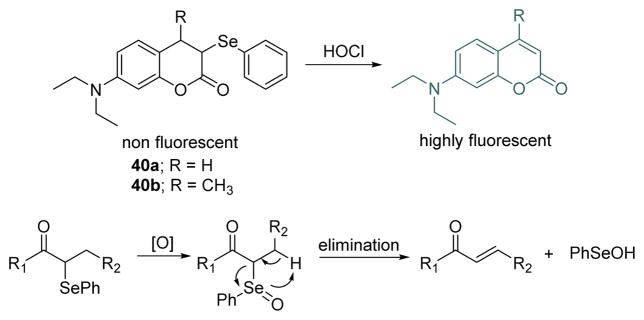

The Jiang group developed a new strategy for HOCl selective fluorescent probes 40a and 40b based on the selenoxide elimination reaction (Fig. 39). The selenoxide elimination has been used in organic synthesis to prepare α,β-unsaturated esters and ketones, olefins and allyl alcohols under mild conditions (Fig. 39).56 The probes 40a and 40b display no major absorption bands or fluorescence emission (Φ < 0.001) over the range of 300–600 nm. With the addition of excess NaClO, the absorption around 370–400 nm and fluorescence centered at 480 nm (40a, Φ = 0.036) and 468 nm (40b, Φ = 0.047) characteristic of the corresponding coumarin dyes, were observed as conjugation is extended. The probes, which featured high sensitivity, selectivity, fast response, and pH independency, were successfully utilized in detecting ClO− in aqueous media and living cells. Importantly, they were used to visualize the generation of endogenous ClO− in progranulocytes and macrophages.

Fig. 39.

Top: reaction of probe 40 and HOCl. Bottom: proposed detection mechanism of HOCl.

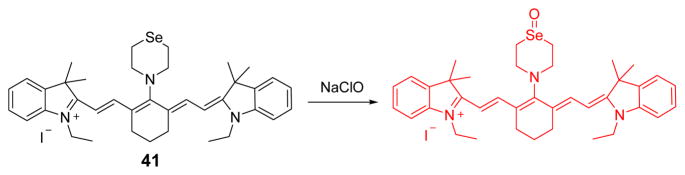

Cyanine dyes have been widely used as NIR fluorescent probes.57 Probe 41 was designed based on a Se-containing heptamethine cyanine dye, and functions as a rapid response, highly selective HOCl probe (Fig. 40). Because of the significant aggregation, 41 exhibits very weak fluorescence in phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4). Upon the addition of HOCl, the probe deaggregates and a strong fluorescent emission at 786 nm is observed. Probe 41 was used to detect HOCl in commercial fetal bovine serum, and to image HOCl in live mice.

Fig. 40.

The reaction of probe 41 and NaClO.

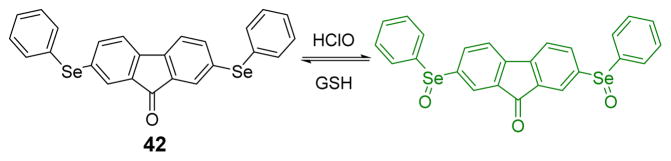

Li and co-workers designed a novel two-photon turn-on probe 42 for HOCl based on 9-fluorenone covalently conjugated to two selenium-containing moieties (Fig. 41).58 Reversible recognition ability of the probe was achieved through redox cycles at the Se center. Results showed reversible and instantaneous responses of the probe towards intracellular HOCl. Moreover, the probe was successfully applied to the two-photon imaging of HOCl levels in zebrafish and mice.

Fig. 41.

The reaction of probe 42 and HOCl.

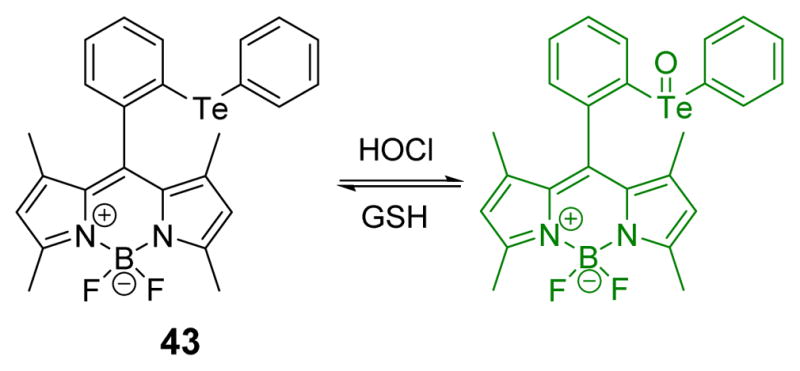

Very recently, Venkatesan and Wu, reasoning that organotellurium compounds are more electron rich than organosulfur and organoselenium compounds, developed a diphenyl telluride-functionalized BODIPY probe to image HOCl (Fig. 42).59 Oxidation by HOCl affords in an increase in emission. Confocal fluorescence microscopy imaging using RAW264.7 cells showed that the probe 43 could be used to evaluate the role of HOCl in biological systems. The probe could be reduced back to the non-florescent reduced state upon addition of glutathione. Fluorescence produced by other ROS and RNS was negligible.

Fig. 42.

The reaction of probe 43 and HOCl.

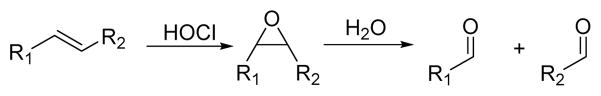

6. Oxidation of double bonds

In organic synthesis, olefinic C=C double bonds can undergo an oxidative cleavage reaction with HOCl under mild conditions. This results in various double bond cleavage products, including relatively unstable chlorinated species that can undergo further oxidation to more stable non-chlorinated species such as aldehydes and carboxylic acids. As shown in scheme 6, conjugation based on C=C bonds may be disrupted by HOCl to afford spectroscopic changes. Based on this concept, several probes have been developed for the detection of HOCl.

Scheme 6.

HOCl-induced double bond cleavage.

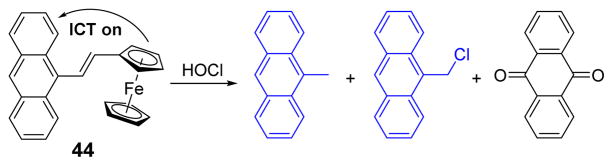

The Ma group designed and synthesized a ferrocene-based fluorescent probe 44.60 Due to an ICT process from the electron-donor ferrocene moiety to anthracene, 44 was non-fluorescent. Upon addition of HOCl, the cleavable double bond linked conjugated molecule was oxidized to produce 9-methylanthracene, 9-(chloromethyl)anthracene and 9,10-dione as confirmed by total ion chromatogram and GC-MS (Fig. 43). This induced 100–fold fluorescent emission enhancement at 441 nm (excitation at 360 nm) in phosphate buffer (30 mM, pH 7.4):THF 1:1 (v/v). Other species including Ag+, Al3+, Ca2+, Cd2+, Cu2+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Hg2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, Pb2+, Zn2+, Cl−, ClO3−, ClO4−, MnO4−, NO2−, NO3−, H2O2, •NO, O2•−, •OH, and ROO• did not cause fluorescent enhancement. Moreover, 44 was cell membrane permeable, and could be used for fluorescence imaging of HOCl in HeLa cells.

Fig. 43.

The reaction of probe 44 and HOCl.

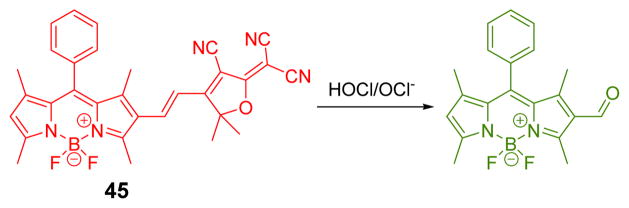

Subsequently, a colorimetric and ratiometric fluorescent probe (45) consisting of a boron-dipyrromethene (BODIPY) dye conjugated with a 2-dicyanomethylene-3-cyano-2,5-dihydrofuran group was developed for the selective and sensitive detection of HOCl.61 The mechanism involves oxidative cleavage of the olefin linker between BODIPY and DCDHF (Fig. 44). The addition of HOCl to 45 triggered a decrease of the initial peak at 614 nm, and growth of new peak at 504 nm in PBS buffer (10 mM pH 7.4) containing 1% ethanol, 0.1% Triton X-100 (v/v). In an analogous manner, the fluorescent emission at 629 nm decreased, and the emission band at 520 nm increased. With properties such as colorimetric and fluorimetric dual-signaling and cell permeability, 45 showed great promise as an efficient tool for biological applications.

Fig. 44.

The reaction of probe 45 and HOCl/ClO−.

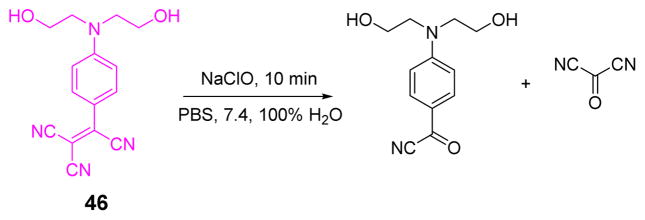

The Zhu team developed a water-soluble tricyanoethylene-derived colorimetric probe 46 for the fast and sensitive detection of ClO− in phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4) (Fig. 45).62 Upon the addition of HOCl, the absorption band centered at 527 nm decreased sharply, accompanied by a solution color changed from pink to colorless. Probe 46 exhibited excellent selectivity toward ClO− over other interfering species. Additionally, 46 could detect ClO− quantitatively in the range of 0–120 μM with a detection limit of 4 μM.

Fig. 45.

The reaction of probe 46 and ClO−.

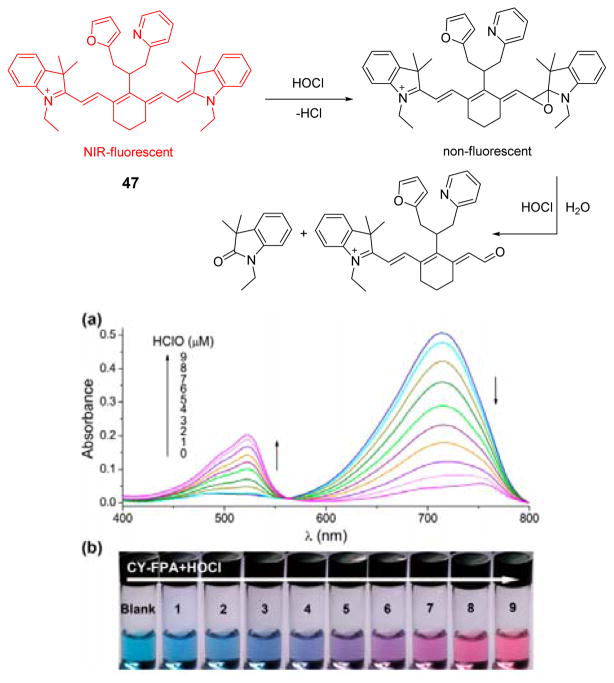

Recently, a novel cyanine based near-infrared fluorescent and colorimetric dual-signal probe 47 was synthesized and characterized.2 As shown in Fig. 46, the reaction mechanism, confirmed by mass spectra, is the electrophilic addition to the polymethine chain, followed by oxidative cleavage. The reaction of 47 with HOCl induced fluorescence quenching at 774 nm in phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4):EtOH 9:1 (v/v). Furthermore, the absorption peak at 710 nm of 47 decreased gradually as a new band at 520 nm grew, accompanied by a color change from blue to purple to pink (Fig. 46). With good cell membrane permeability and low cytotoxicity, 47 could be used as a new fluorescent probe for HOCl imaging in live cells. In addition, enzymatic activity of MPO could be evaluated on the basis of a colorimetric method.

Fig. 46.

Top: reaction of probe 47 and HOCl. Bottom: (a) UV-vis responses of 47 to HOCl and the corresponding color changes. Reprinted with permission from Anal. Chem., 2014, 86, 671–677. Copyright 2014, American Chemical Society.

7. Oxidation of cuprous to cupric

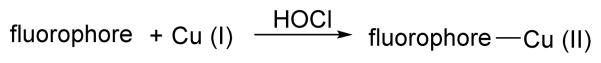

With strong coordination ability, Cu (II) is a widely used candidate for displacement detection of HOCl. Based on the reaction of HOCl that oxidizes Cu (I) to Cu (II) specifically, chemosensors that are unresponsive to Cu (I) but sensitive to Cu (II) have been developed for the indirect detection of HOCl (Scheme 7).

Scheme 7.

The specific oxidation reaction of cuprous to cupric with HOCl.

The Li group firstly applied a rhodamine derivative 48 for HOCl detection via copper oxidation (Fig. 47).63 The UV-vis spectra of probe 48 with cuprous ions was nearly overlapped with the baseline in Tris buffer (10 mM, pH 7.0):CH3CN 1:1 (v/v). Upon addition of HOCl, a new absorption peak at 555 nm appeared gradually, accompanied with a color change from colorless to magenta. Kinetics studies revealed that the detection process was complete within 6 min. Furthermore, representative species such as CO32−, SO42−, ClO4−, ClO3−, NO2−, AcO−, and P2O74− elicited no interference, except for H2O2. With a detection limit as low as 0.81 μM, 48 could be used in real water samples.

Fig. 47.

Proposed detection mechanism of ClO− by probe 48.

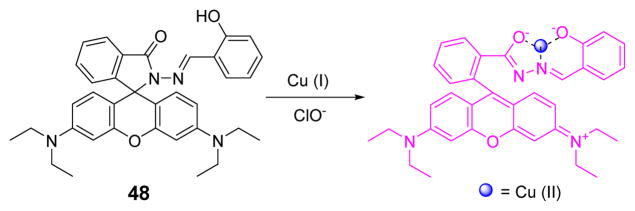

Based on the previous work, another colorimetric ClO− probe 49 was developed using an azobenzene acid by the Li team (Fig. 48).64 Utilizing the oxidant of ClO− properties of HOCl and the varying coordinating properties of Cu (I) and Cu (II), the addition of HOCl to the system of 49 and cuprous ions induced the red solution to turn yellow. Other anions, including HPO42−, H2PO4−, SO42−, Cl−, ClO4−, HSO3−, Br−, PO43−, CO32−, I−, HCO3−, SO32−, F−, AcO−, HSO4−, NO2−, ClO3−, IO3− and H2O2, has insignificant effect on the spectroscopic properties of 49 and ClO−. The high sensitivity and selectivity of 49 can render it an efficient chemosensor for ClO− in pure aqueous solutions.

Fig. 48.

Proposed detection mechanism of HOCl by probe 49.

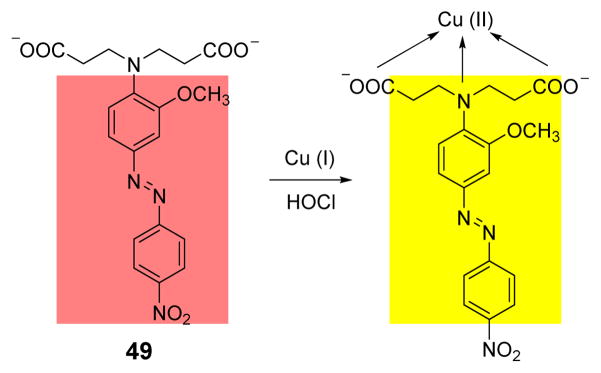

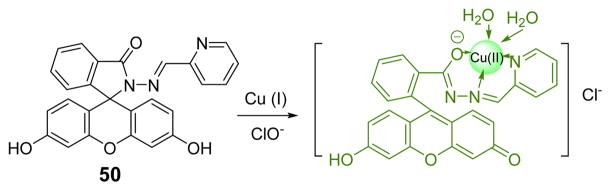

The Yin group designed and synthesized a fluorescein derivative, 50, for the detection of ClO− (Fig. 49).7 Upon oxidation of Cu (I) to Cu (II), the colorless solution changed to magenta at pH 7.0. The Cu (II) complex was found to undergo further reaction to afford green fluorescence upon storage for a few hours. Other common anions, including F−, Cl−, ClO3−, NO2−, CN−, S2−, SCN−, P2O74−, AcO−, CO32−, SO42−, ClO4−, did not interfere with ClO− detection, except for H2O2. The colorimetric and fluorescent responses made it promising for the detection of ClO− in tap water.

Fig. 49.

Proposed detection mechanism of HOCl by probe 50.

In an interesting and somewhat related but unique recent study, Park et al. developed blue silver DNA-encapsulated nanodots that enable the effective detection of HOCl in industrial cleaners.65

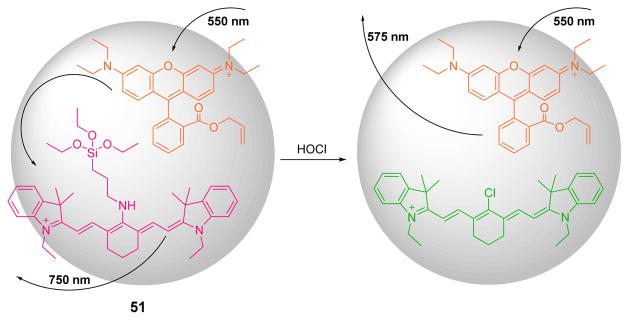

In addition, The Peng group developed a novel specific ratiometric nanoprobe 51 based on the FRET process (Fig. 50).66 By embedding an aminocyanine dye as the ClO− probe and the FRET acceptor, and rhodamine B as the FRET donor, the excitation wavelength at 550 nm would induce strong fluorescent emission at 750 nm. However, bleaching of aminocyanine dye by HOCl interrupted the FRET interaction, and the fluorescence spectrum of 51 exhibited a ratiometric change at 750 nm and at 575 nm. The large spectral separation eliminated the interference from each emission. A study of the reactivity of 51 towards various ROS, cations and anions confirmed its high selectivity towards ClO−. The nanoprobe could further be used to visualize the ClO− produced in HeLa cells.

Fig. 50.

Proposed detection mechanism of HOCl when using probe 51.

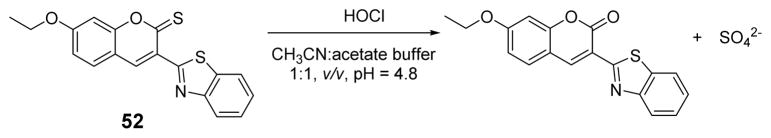

The Chang group developed an HOCl-selective colorimetric and fluorogenic signaling probe 52 based on oxidation of a thiocarbonyl by HOCl (Fig. 51).67 The absorption peaks of 52 at 325 nm and 443 nm decreased and a new band at 384 evolved upon the addition of HOCl to a solution of 52 in acetate buffer (10 mM, pH 4.8):CH3CN 1:1 (v/v). The initially yellow solution turned colorless upon HOCl addition. HOCl was shown to induce a prominent (up to 250-fold) fluorescence enhancement at 465 nm. The detection limit of 52 towards HOCl was 0.83 μM. Except for Hg2+, in the presence of common metal ions and anions, probe 52 displayed high selectivity for HOCl. However, interference from Hg2+ ions was successfully removed by using Br− as a masking agent. In chemical and environmental samples 52 could be useful for the determination of HOCl.

Fig. 51.

Reaction of probe 52 and HOCl.

Concluding remarks

In this review, we have summarized recent progress towards the use of HOCl oxidation in the design of sensors and imaging agents for HOCl. The examples reported can be classified into seven reaction types according to their oxidation mechanisms. The oxidation of p-methoxyphenols, p-aminophenol analogues and oximes are the most widely used approaches for HOCl detection. Thioesters and amides mainly undergo chlorination reactions, whereas thioethers and selenides are generally oxidized to produce the corresponding sulfonate and selenoxide. The cleavage of carbon-carbon double bonds takes place in electron-rich conjugated probe systems. Probes exhibiting emission changes in the presence of HOCl are being and used in imaging and labeling. In addition, NIR dyes that are being modified to serve as HOCl probes will enable relatively deep tissue penetration and minimal auto-fluorescence background.2,4,5,30,51,57,66

Importantly, probes that can evaluate the role of MPO, HOCl and other related species in biological processes promote vital progress and insight into human disease.2,4,30 For example, the role of HOCl in regulating inflammation and cellular apoptosis is attracting increased current attention. As recently noted, however, the specific organelle(s) involved in the distribution of HOCl remain unknown.47 Finally, effective tools for detecting HOCl at subcellular levels remains a major challenge due to its low concentration, strong oxidizing properties, and short lifetime. We hope that this review will inspire further research into the improved design of probes and sensors for HOCl that may help clarify its role in biology and enable its efficient environmental monitoring.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21102086, 21472118), the Shanxi Province Science Foundation for Youths (No. 2012021009-4, 2013011011-1), the Shanxi Province Foundation for Returnee (No. 2012-007), the Taiyuan Technology Star Special (No. 12024703), the Program for the Top Young and Middle-aged Innovative Talents of Higher Learning Institutions of Shanxi (2013802), Talents Support Program of Shanxi Province (2014401), the CAS Key Laboratory of Analytical Chemistry for Living Biosystems Open Foundation (ACL201304) and the National Institutes of Health (R15EB016870).

Notes and references

- 1.Vijayaraghavan K, Ramanujam TK, Balasubramanian N. Waste Manage. 1999;19:319–323. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun MT, Yu H, Zhu HJ, Ma F, Zhang S, Huang DJ, Wang SH. Anal Chem. 2014;86:671–677. doi: 10.1021/ac403603r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ye ZQ, Zhang R, Song B, Dai ZC, Jin DY, Goldys EM, Yuan JL. Dalton Trans. 2014;43:8414–8420. doi: 10.1039/c4dt00179f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shepherd J, Hilderbrand SA, Waterman P, Heinecke JW, Weissleder R, Libby P. Chem Biol. 2007;14:1221–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koide Y, Urano Y, Hanaoka K, Terai T, Nagano T. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:5680–5682. doi: 10.1021/ja111470n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.David IP, Michael JD. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14:1453–1464. doi: 10.1021/tx0155451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huo FJ, Zhang JJ, Yang YT, Chao JB, Yin CX, Zhang YB, Chen TG. Sens Actuators B. 2012;166–167:44–49. [Google Scholar]

- 8.David IP, Michael JD. Biochem. 2006;45:8152–8162. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yap YW, Whiteman M, Cheung NS. Cell Signal. 2007;19:219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sam CH, Lu HK. J Dent Sci. 2009;4(2):45–54. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Favero TG, Colter D, Hooper PF, Abramson JJ. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84:425–430. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman ALP, Winterbourn CC, Brennan SO, Jordan TW, Kettle AJ. Biochem J. 2003;375:33–40. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin JG, Campbell HR, Iijima H, Gautrin D, Malo JL, Eidelman DH, Hamid Q, Maghni K. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:568–574. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200201-021OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gebicka L, Banasiak E. Toxicol In Vitro. 2012;26:924–929. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adam LC, Gordon G. Anal Chem. 1995;67:535–540. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krivis AF, Gazda ES. Anal Chem. 1967;39:226–227. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thiagarajan S, Wu ZY, Chen SM. J Electroanal Chem. 2011;661:322–328. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun ZN, Liu FQ, Chen Y, Tam PKH, Yang D. Org Lett. 2008;10:2171–2174. doi: 10.1021/ol800507m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu JJ, Wong NK, Gu QS, Bai XY, Ye S, Yang D. Org Lett. 2014;16:3544–3547. doi: 10.1021/ol501496n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cui K, Zhang DQ, Zhang GX, Zhu DB. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:6052–6055. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang WJ, Guo C, Liu LB, Qin JG, Yang CL. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:5560–5563. doi: 10.1039/c1ob05550j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou Y, Li JY, Chu KH, Liu K, Yao C, Li JY. Chem Commun. 2012;48:4677–4679. doi: 10.1039/c2cc30265a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yue YK, Yin CX, Huo FJ, Chao JB, Zhang YB. Sens Actuators B. 2014;202:551–556. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin WY, Long LL, Chen BB, Tan W. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:2305–2309. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi J, Li QQ, Zhang X, Peng M, Qin JG, Li Z. Sens Actuators B. 2010;145:583–587. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang DQ. Spectrochim Acta A. 2010;77:397–401. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2010.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao N, Wu YH, Wang RM, Shi LX, Chen ZN. Analyst. 2011;136:2277–2282. doi: 10.1039/c1an15030h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng XH, Jia HZ, Long T, Feng J, Qin JG, Li Z. Chem Commun. 2011;47:11978–11980. doi: 10.1039/c1cc15214a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu GF, Zeng F, Wu SZ. Anal Met. 2013;5:5589–5596. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou Y, Pei WB, Wang CY, Zhu JX, Wu JS, Yan QY, Huang L, Huang W, Yao C, Loo JSC, Zhang QC. Small. 2014;10:3560–3567. doi: 10.1002/smll.201303127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao LY, Zhang R, Zhang WZ, Du ZB, Liu CJ, Ye ZQ, Song B, Yuan JL. Biomaterials. 2015;68:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen WC, Venkatesan P, Wu SP. Anal Chim Acta. 2015;882:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen XQ, Wang XC, Wang SJ, Shi W, Wang K, Ma HM. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:4719–4724. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang YK, Cho HJ, Lee J, Shin I, Tae J. Org Lett. 2009;11:859–861. doi: 10.1021/ol802822t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhan XQ, Yan JH, Su JH, Wang YC, He J, Wang SY, Zheng H, Xu JG. Sens Actuators B. 2010;150:774–780. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen XQ, Lee KA, Ha EM, Lee KM, Seo YY, Choi HK, Kim HN, Kim MJ, Cho CS, Lee SY, Lee WJ, Yoon J. Chem Commun. 2011;47:4373–4375. doi: 10.1039/c1cc10589b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jia J, Ma HM. Chinese Sci Bull. 2011;56:3266–3272. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wei FF, Lu Y, He S, Zhao LC, Zeng XS. Anal Methods. 2012;4:616–618. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang X, Zhang YX, Zhu ZJ. Anal Met. 2012;4:4334–4338. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu QL, Lee KA, Lee SY, Lee KM, Lee WJ, Yoon JY. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:9944–9949. doi: 10.1021/ja404649m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doura T, An Q, Sugihara F, Matsuda T, Sando S. Chem Lett. 2011;40:1357–1359. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao YN, Zhang R, Ye ZQ, Dai ZC, An HY, Yuan JL. Anal Chem. 2012;84:10785–10792. doi: 10.1021/ac3028189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu FN, Nabeshima T. Dalton Trans. 2014;43:9529–9536. doi: 10.1039/c4dt00616j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo T, Cui L, Shen JN, Wang R, Zhu WP, Xu YF, Qian XH. Chem Commun. 2013;49:1862–1864. doi: 10.1039/c3cc38471c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kenmoku S, Urano Y, Kojima H, Nagano T. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7313–7318. doi: 10.1021/ja068740g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hwang J, Choi MG, Bae J, Chang SK. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:7011–7015. doi: 10.1039/c1ob06012k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yuan L, Wang L, Agrawalla BK, Park SJ, Zhu H, Sivaraman B, Peng JJ, Xu QH, Chang YT. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:5930–5938. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang J, Wang XL, Yang XR. Analyst. 2012;137:2806–2812. doi: 10.1039/c2an35239g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu XJ, Li Z, Yang L, Han JH, Han SF. Chem Sci. 2013;4:460–467. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu LX, Zhang J, Yang XR. Sens Actuators B. 2013;184:189–195. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Best QA, Sattenapally N, Dyer DJ, Scott CN, McCarroll ME. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:13365–13370. doi: 10.1021/ja401426s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang R, Ye ZQ, Song B, Dai ZC, An X, Yuan JL. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:10325–10331. doi: 10.1021/ic400767u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu SR, Vedamalai M, Wu SP. Anal Chim Acta. 2013;800:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu SR, Wu SP. Org Lett. 2013;15:878–881. doi: 10.1021/ol400011u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lou ZR, Li P, Pan Q, Han KL. Chem Commun. 2013;49:2445–2447. doi: 10.1039/c3cc39269d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li GP, Zhu DJ, Liu Q, Xue L, Jiang H. Org Lett. 2013;15:2002–2005. doi: 10.1021/ol4006823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheng GH, Fan JL, Sun W, Cao JF, Hu C, Peng XJ. Chem Commun. 2014;50:1018–1020. doi: 10.1039/c3cc47864e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang W, Liu W, Li P, Qkang J, Wang JY, Wang H, Tang B. Chem Commun. 2015;51:10150–10153. doi: 10.1039/c5cc02537k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Venkatesan P, Wu SP. Analyst. 2015;140:1349–1355. doi: 10.1039/c4an02116a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen SM, Lu JX, Sun CD, Ma HM. Analyst. 2010;135:577–582. doi: 10.1039/b921187j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Park J, Kim H, Choi Y, Kim Y. Analyst. 2013;138:3368–3371. doi: 10.1039/c3an36820c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu BC, Xu YH, Liu WQ, Shao CX, Wua HF, Jiang HL, Dua B, Zhang XL. Sens Actuators B. 2014;191:473–478. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lou XD, Zhang Y, Li QQ, Qin JG, Li Z. Chem Commun. 2011;47:3189–3191. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04911e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lou XD, Zhang Y, Qin JG, Li Z. Sens Actuators B. 2012;161:229–234. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park S, Choi S, Yu JH. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2014;9:129–136. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-9-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen GW, Song FL, Wang JY, Yang ZG, Sun SG, Fan JL, Qiang XX, Wang X, Dou BR, Peng XJ. Chem Commun. 2012;48:2949–2951. doi: 10.1039/c2cc17617c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moon JO, Lee JW, Choi MG, Ahn S, Chang SK. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:6594–659. [Google Scholar]