Abstract

Actinobaculum schaalii is a Gram-positive facultative anaerobe bacillus. It is a commensal organism of the genitourinary tract. Its morphology is nonspecific. Aerobic culture is tedious, and identification techniques have long been inadequate. Thus, A. schaalii has often been considered as a nonpathogen bacterium or a contaminant. Its pathogenicity is now well described in urinary tract infections, and infections in other sites have been reported. This pathogen is considered as an emerging one following the growing use of mass spectrometry identification. In this context, the aim of our study was to evaluate the number of isolations of A. schaalii before and after the introduction of mass spectrometry in our hospital and to study the clinical circumstances in which isolates were found.

Keywords: Actinobaculum schaalii, Actinotignum schaalii, emerging infections, Gram-positive bacilli, mass spectrometry, urinary tract infections

Résumé

Actinobaculum schaalii est un bacille à Gram positif anaérobie facultatif. Il s'agit d'un germe commensal du tractus génito-urinaire. Sa morphologie est aspécifique. La culture est fastidieuse en aérobiose et les techniques d'identification ont longtemps été insuffisantes. De ce fait, il a souvent été considéré comme un germe non pathogène ou un contaminant. Sa pathogénicité est aujourd'hui bien décrite dans les infections urinaires, mais des infections au niveau d'autres sites ont été rapportées. Ce pathogène considéré comme émergent, voit en réalité son nombre d'isolats augmenter depuis l'introduction de la spectrométrie de masse. Dans ce contexte, le but de notre étude est d'évaluer le nombre d'isolements d'Actinobaculum schaalii avant et après l'introduction de la spectrométrie de masse dans notre centre hospitalier et d'étudier les circonstances cliniques dans lesquelles ces isolats ont été retrouvés.

Mots-clés: Actinotignum schaalii, Actinobaculum schaalii, bacilles à Gram positif, infections émergentes, infections urinaires, spectrométrie de masse

Introduction

Actinobaculum schaalii is a Gram-positive bacillus that was described for the first time in 1997 [1]. Other species described in the same genus include Actinobaculum suis, Actinobaculum urinale and Actinobaculum massiliense. A. suis has been reported as a veterinary pathogen [2], [3]. A. urinale is rarely found in human infections but has been coisolated with A. schaalii [4]. Recent changes in the classification were made, reclassifying A. schaalii as Actinotignum schaalii [5]. It is a nonsporulated bacillus. Its morphology is nonspecific, and it sometimes looks like immobile corynebacteria. It is facultative anaerobic, which implies a possible anaerobic culture and culture in atmosphere supplemented with 5% CO2. Its aerobic culture is tedious and is facilitated by the use of blood-enriched media. These characteristics explain the difficulty of isolation, especially from urine, which is routinely incubated aerobically on unsupplemented media, such as chromogenic ones. A. schaalii is described as a commensal of the urogenital tract also found on the skin [6]. Many cases of infections have been reported, and urinary tract infections (UTIs) seem to predominate, particularly among elderly patients [7], [8]. However, other types of infections exist. Since its discovery, the number of reported isolates and clinical cases is increasing. It is thus considered to be an emerging pathogen.

The aim of our study was to assess retrospectively the frequency and circumstances of isolation of A. schaalii over 10 years in CH Versailles (France) and the role of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) in the identification of this bacterium.

Materials and Methods

Using SIRScan software (I2A), we extracted all A. schaalii strains between July 2004 and February 2015. Strains were identified by sequencing of the 16S ribosomal DNA from colonies using the primers A2 (5′-AGAGTTTGATCATGGCTCAG-3′) and S15 (5′-GGGCGGTGTGTACAAGGCC-3′) [9] until November 2011. From December 2011, MALDI-TOF (Microflex; Bruker Daltonics, Wissembourg, France) was used (databases DB 4613 and 5627). Retrospective mass spectrometry (MS) identification was carried out for stored isolates initially identified by sequencing.

For urine samples, microscopic examination (Gram coloration) was carried out in case of leukocyturia >104 leucocytes/mL. Ten microlitres was routinely seeded onto a chromogenic agar incubated aerobically. If microscopic examination showed only Gram-positive bacilli, blood agar was also seeded under atmosphere enriched in CO2 for 48 hours.

Clinical observations of all cases were reviewed to determine the pathogenic role of the isolate. The following informations were collected: age, sex, infection risk factors, site and isolation circumstances. We considered that A. schaalii was a pathogen when it was clearly mentioned in the actual benefit account and/or when it was the only bacteria isolated from the infectious site.

Results

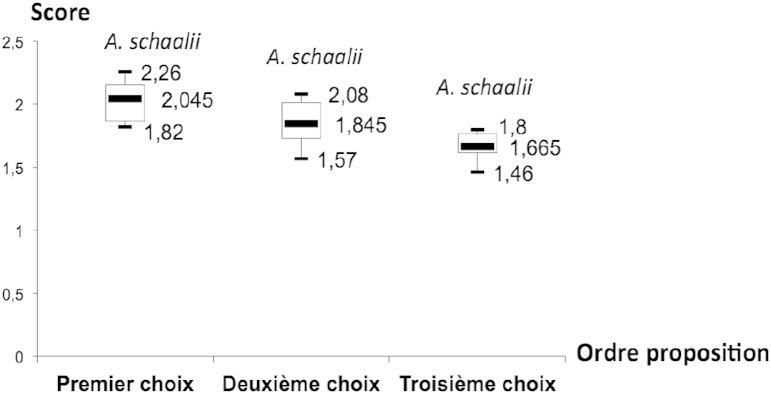

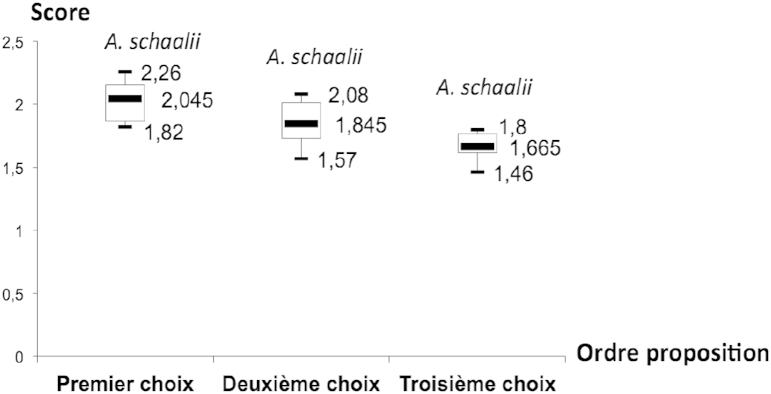

Between July 2004 and February 2015, a total of 24 A. schaalii isolates were collected from 24 patients. Six isolates were initially identified by sequencing, and the other 18 were identified by MALDI-TOF. Among the six isolates initially identified by sequencing, three were further confirmed by MS. The results of the different scores obtained are shown in Table 1. For isolates identified by MS, the statistical averages of the scores obtained for each of the first three proposed identifications are shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Retrospective mass spectrometry identification of three Actinobaculum schaalii isolatesa

| Isolate no. | Identification (score): |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| First choice | Second choice | Third choice | |

| 1 | A. schaalii (2.03) | A. schaalii (2) | A. schaalii (1.8) |

| 2 | A. schaalii (2.15) | A. schaalii (1.75) | A. schaalii (1.63) |

| 3 | A. schaalii (1.93) | A. schaalii (1.57) | A. schaalii (1.54) |

Isolates were initially identified by sequencing.

Fig. 1.

Statistical scores (maximum, median, minimum) for first three proposals (17 isolates).

The circumstances of isolation and the clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 2. Strains were predominantly isolated from abscesses and collections (58% of cases, 14 isolates): bone infections and soft tissue infections including cysts and abscesses (wall, pilonidal sinus, breast, ankle etc.). The urine samples corresponded to 33% of the isolates: eight cases, including seven cases after November 2011 (Table 3). Finally, blood cultures represented two isolates. Urine and blood cultures were monomicrobial, while 64% (9/14) abscesses and collections were plurimicrobial.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients

| Patient no. | Age/sex | Risk factor | Nature of sampling | Other microorganism(s) | Accountability Actinobaculum schaalii | Diagnosis retained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58/F | Cancer | Blood culture | No | No | Staphylococcus epidermidis portacath infection |

| 2 | 55/M | Monoclonal gammopathy | Blood culture | No | No | Enterobacter cloacae sepsis |

| 3 | 8/M | Undescended testis, enuresis | Urine | No | Yes | UTI |

| 4 | 81/M | Age, squamous cell carcinoma | Urine | No | Yes | UTI |

| 5 | 83/F | Age, diabetes | Urine | No | Yes | UTI |

| 6 | 83/F | Age, colectomy, villous tumor | Urine | No | Yes | UTI |

| 7 | 96/F | Age, urinofaecal incontinence | Urine | No | Yes | UTI |

| 8 | 75/F | Age | Urine | No | Yes | UTI |

| 9 | 80/M | Age | Urine | No | Yes | UTI |

| 10 | 66/M | Age | Urine | No | Yes | UTI |

| 11 | 77/M | Age, diabetes | Collection | No | Yes | Osteoarthritis |

| 12 | 23/M | None | Collection | No | Yes | Abdominal wall abscess |

| 13 | 69/M | Age | Collection | No | Yes | Secondarily infected sebaceous cyst |

| 14 | 20/F | None | Collection | No | Yes | Pilonidal sinus abscess |

| 15 | 34/F | None | Collection | No | Yes | Breast abscess |

| 16 | 17/M | None | Collection | Peptostreptococcus spp. | No | Malleolus abscess |

| 17 | 28/M | None | Collection | Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecalis | No | Collection of left tibia |

| 18 | 56/M | Diabetes | Collection | Streptococcus spp., Peptostreptococcus spp. | No | Secondarily infected sebaceous cyst |

| 19 | 74/F | Age | Collection | Actinomyces spp., Peptoniphilus spp. | No | Lipoma secondarily infected |

| 20 | 69/M | Age, diabetes | Collection | Finegoldia spp., Anaerococcus spp. | No | Diabetic foot ulcer |

| 21 | 54/F | Diabetes | Collection | Acinetobacter spp., Helcococcus spp., Anaerococcus spp. | No | Abscess on sternotomy |

| 22 | 77/M | Age | Collection | P. mirabilis, Morganella morganii | No | Ankle osteitis |

| 23 | 27/F | None | Collection | Actinomyces turicensis | No | Vaginal abscess |

| 24 | 88/F | Age | Collection | Staphylococcus aureus, Fascioloides magna, Propionibacterium acnes | No | Shoulder fistula |

UTI, urinary tract infection.

Table 3.

Sites of isolation of A. schaalii before and after introduction of MS

| Introduction of MS | Urine | Abscess/collection | Blood culture | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | 1 | 5 | 0 | 6 |

| After | 7 | 9 | 2 | 18 |

MS, mass spectrometry.

The male/female sex ratio of the 24 patients was 1.2 with a mean age of 58.2 years (range, 8–96 years). In 75% of cases, at least one risk factor for infection was present, including age >65 years, immunosuppression, abnormality of the genitourinary tract and diabetes.

Discussion

Introduction of MALDI-TOF in clinical practice has led to an increase in the frequency of A. schaalii isolates in our laboratory (Table 3). Indeed, between July 2004 and November 2011, six strains of A. schaalii were identified by sequencing, vs. 18 isolates by MS since November 2011. The most likely explanation is that before November 2011, routine bacterial identification was performed by biochemical tests such as API strips (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) or Vitek cards (bioMérieux). These techniques did not permit the identification of A. schaalii because this organism was then not included in the database [10]; the latest 2015 version of the map Vitek anaerobe and Corynebacterium (ANC) now allows its detection.

Analysis of the results of identification by MS (Fig. 1) revealed that the first three proposals correspond to the three spectra of A. schaalii of Bruker base (Table 4) in 17 of 18 cases, with a median identification score of 2.045 (1.82 to 2.26) for the first proposal. The three other Actinobaculum species in the database are never proposed. In addition, retrospective MS performed on three isolates stored and previously identified by 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing was successful for identification. As previously described [10], we confirmed the identification performance by Microflex MALDI-TOF (Bruker) for A. schaalii with the three strains also identified by sequencing. However, it was reported that the MALDI-TOF Vitek (bioMérieux) does not currently allow the identification of A. schaalii [11], [12].

Table 4.

Mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics) local database for Actinobaculum spp.

| Species | Database entry |

|---|---|

| Actinobaculum schaalii | 70710715001 MVC |

| A. schaalii | DSM 15541T DSM |

| A. schaalii | RV_BA1_032010_E LBK |

| Actinobaculum suis | DSM 20639T DSM |

| A. suis | GD75 GDD |

| Actinobaculum urinale | DSM 15805T DSM |

The pathogenic role of A. schaalii was not accepted by clinicians in two cases of bacteraemia because another recognized pathogen was isolated from blood cultures for each of the two patients. In addition, the presence of this microorganism as a contaminant of blood cultures suggests a possible presence on the skin [6]. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude its participation in the infection.

Urine samples all exhibited significant leukocyturia (>104/mL), a positive direct microscopic examination with Gram-positive bacilli and monomicrobial culture >105 CFU/mL. The isolation in urine requires seeding on a blood agar in atmosphere enriched in CO2. This is routinely carried out in our laboratory on urine samples with leukocyturia (>104/mL) and Gram-positive bacilli on microscopic examination. The collected clinical data are consistent with a diagnosis of infection of the urogenital tract. A. schaalii is thus responsible for UTI in eight cases. One or more risk factors were found in these patients, highlighting the opportunistic nature of the microorganism. Advanced age is one of those risk factors (seven of eight patients were aged >65 years) with urinary infection of A. schaalii. However, infections in young subjects should not be excluded [13], as evidenced by case of acute pyelonephritis in a 8-year-old patient.

To assess the clinical relevance of A. schaalii, its isolation in urine samples must be associated with symptoms of UTI because it is important to remember that it can sometimes be a urinary commensalism. As such, a prospective Danish study showed that A. schaalii could be detected by PCR in urine in more than 22% of patients aged >60 years, despite the absence of clinical signs in certain cases [14]. This may explain why A. schaalii is often reported to exist within polymicrobial urine [15]. In our practice, when there is a dominant uropathogen, the other possibly associated bacteria are not always identified, as they are considered commensal.

For abscesses and collections, we distinguish between mono- and plurimicrobial samples. Accountability is questionable for samples with various microorganisms. It is easier when there are no other related bacteria. This is the case of a 34-year-old patient with recurrent breast abscess, in which A. schaalii was clearly implicated, as specified in the medical report. As in most of the cases we have described, the patients were treated by surgery only without antibiotics, and the outcome was always good, suggesting that, unlike UTIs, antibiotic treatment is not routinely required to treat the infection. We emphasize that compared to urinary isolates, the age of the patient is more important for abscesses and collection. Another difference concerns young patients without risk factors, including an abdominal wall abscess in a 23-year-old patient, a pilonidal sinus abscess in a 20-year-old man and breast abscesses observed in a 34-year-old patient. However, it was suggested that A. schaalii could contribute to the infectious process even when it is isolated in the presence of other bacteria [15]. Cases of endocarditis [16], Fournier gangrene [17], spondylitis [18] and urosepsis [19] have already been reported, underscoring the invasive potential of this microorganism.

Overall, although UTIs are the most frequently reported in the literature [12], our study shows that the isolation of A. schaalii in abscesses and collections is common. The frequency of isolation has increased since the onset of use of MS in our laboratory. This suggests that the emerging nature of infections due to A. schaalii is probably attributable to gaps in methods for identifying in the daily microbiology before the era of MS.

To conclude, our study emphasizes the role of MALDI-TOF in the accurate identification of A. schaalii. This process, which is less-time consuming and less expensive than molecular biology, advantageously replaces biochemical tests in the identification of this organism. The emergence of this bacterium presumably is the result, at least in part, of an evolution in identification methods. This will permit a better understanding of the epidemiology of A. schaalii. The pathogenic role of A. schaalii is questionable in some cases. Further studies are therefore needed, especially on the cutaneous habitat and virulence of this bacterium, to better interpret its presence in a clinical sample.

Acknowledgement

We thank B. Couzon for technical contributions.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Lawson P.A., Falsen E., Akervall E., Vandamme P., Collins M.D. Characterization of some Actinomyces-like isolates from human clinical specimens: reclassification of Actinomyces suis (Soltys and Spratling) as Actinobaculum suis comb. nov. and description of Actinobaculum schaalii sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:899–903. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-3-899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker R.L., MacLachlan N.J. Isolation of Eubacterium suis from sows with cystitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1989;195:1104–1107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamini B., Slocombe R.F. Porcine abortion caused by Actinomyces suis. Vet Pathol. 1988;25:323–324. doi: 10.1177/030098588802500415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fendukly F., Osterman B. Isolation of Actinobaculum schaalii and Actinobaculum urinale from a patient with chronic renal failure. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3567–3569. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3567-3569.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yassin A.F., Spröer C., Pukall R., Sylvester M., Siering C., Schumann P. Dissection of the genus Actinobaculum: reclassification of Actinobaculum schaalii Lawson et al. 1997 and Actinobaculum urinale Hall et al. 2003 as Actinotignum schaalii gen. nov., comb. nov. and Actinotignum urinale comb. nov., description of Actinotignum sanguinis sp. nov. and emended descriptions of the genus Actinobaculum and Actinobaculum suis; and re-examination of the culture deposited as Actinobaculum massiliense CCUG 47753T (= DSM 19118T), revealing that it does not represent a strain of this species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;65:615–624. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.069294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsen A.B., Andersen P.K., Bank S., Søby K.M., Lund L., Prag J. Actinobaculum schaalii, a commensal of the urogenital area. BJU Int. 2013;112:394–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bank S., Jensen A., Hansen T.M., Søby K.M., Prag J. Actinobaculum schaalii, a common uropathogen in elderly patients, Denmark. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:76–80. doi: 10.3201/eid1601.090761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nielsen H.L., Søby K.M., Christensen J.J., Prag J. Actinobaculum schaalii: a common cause of urinary tract infection in the elderly population. Bacteriological and clinical characteristics. Scand J Infect Dis. 2010;42:43–47. doi: 10.3109/00365540903289662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bercot B., Kannengiesser C., Oudin C., Grandchamp B., Sanson-le Pors M.J., Mouly S. First description of NOD2 variant associated with defective neutrophil responses in a woman with granulomatous mastitis related to corynebacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:3034–3037. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00561-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuuminen T., Suomala P., Harju I. Actinobaculum schaalii: identification with MALDI-TOF. New Microbes New Infect. 2014;2:38–41. doi: 10.1002/2052-2975.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Brun C., Robert S., Bruyere F., Lanotte P. [Emerging uropathogens: point for urologists and biologists] Prog Urol. 2015;25:363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2015.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cattoir V. Actinobaculum schaalii: review of an emerging uropathogen. J Infect. 2012;64:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen L.B., Bank S., Hertz B., Søby K.M., Prag J. Actinobaculum schaalii, a cause of urinary tract infections in children? Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992. 2012;101:e232–e234. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bank S., Hansen T.M., Søby K.M., Lund L., Prag J. Actinobaculum schaalii in urological patients, screened with real-time polymerase chain reaction. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2011;45:406–410. doi: 10.3109/00365599.2011.599333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tschudin-Sutter S., Frei R., Weisser M., Goldenberger D., Widmer A.F. Actinobaculum schaalii—invasive pathogen or innocent bystander? A retrospective observational study. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:289. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoenigl M., Leitner E., Valentin T., Zarfel G., Salzer H.J., Krause R. Endocarditis caused by Actinobaculum schaalii, Austria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1171–1173. doi: 10.3201/eid1607.100349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanden Bempt I., Van Trappen S., Cleenwerck I., De Vos P., Camps K., Celens A. Actinobaculum schaalii causing Fournier's gangrene. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2369–2371. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00272-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haller P., Bruderer T., Schaeren S., Laifer G., Frei R., Battegay M. Vertebral osteomyelitis caused by Actinobaculum schaalii: a difficult-to-diagnose and potentially invasive uropathogen. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26:667–670. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0345-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Brun C., Robert S., Bruyere F., Tanchoux C., Lanotte P. Urinary tract infection caused by Actinobaculum schaalii: a urosepsis pathogen that should not be underestimated. JMM Case Rep. 2015;2(2) [Google Scholar]

References

Introduction

Actinobaculum schaalii est un bacille à Gram positif décrit pour la première fois en 1997 [1]. D'autres espèces ont été décrites dans le même genre : Actinobaculum suis, Actinobaculum urinale et Actinobaculum massiliense. A. suis a été rapporté comme étant un pathogène vétérinaire [2], [3]. A. urinale est rarement retrouvé chez l'homme. Il a néanmoins déjà été isolé avec A. schaalii [4]. De récents changements dans la classification ont été effectués, reclassifiant Actinobaculum schaalii en Actinotignum schaalii [5]. Nous continuerons à utiliser l'ancienne dénomination pour la suite de l'article. Il s'agit d'un bacille à Gram positif asporogène. Sa morphologie est aspécifique et est parfois rapprochée de celle des corynébactéries. Il est immobile à l'état frais. Il est anaérobie facultatif, ce qui implique une culture possible en anaérobiose et en atmosphère enrichie de 5% CO2. Sa culture est fastidieuse en aérobiose et est facilitée par les milieux additionnés de sang. Cela explique sa difficulté d'isolement, en particulier dans les urines où seule une culture en aérobiose sur milieu non enrichi, chromogénique par exemple, est généralement réalisée. A. schaalii est décrit comme étant un commensal du tractus uro-génital, y compris sur la peau [6]. De nombreux cas d'infections ont été signalés, et les infections urinaires semblent prédominer, en particulier chez les patients âgés [7], [8]. Toutefois, d'autres types d'infections existent. Depuis sa découverte, le nombre d'isolements et de cas cliniques rapportés est en augmentation. Il est ainsi considéré comme un pathogène émergent.

Le but de notre travail est d'étudier rétrospectivement la fréquence et les circonstances d'isolement d'A. schaalii sur une période de 10 ans au CH de Versailles (France) ainsi que l'apport de la spectrométrie de masse de type MALDI- TOF dans l'identification de cette bactérie.

Matériels et méthodes

A l'aide du logiciel SIRScan (I2A), nous avons extrait toutes les souches identifiées A. schaalii entre juillet 2004 et février 2015. Elles ont été identifiées par séquençage de l'ADN ribosomal 16S à partir de colonies à l'aide des amorces A2 (5′AGAGTTTGATCATGGCTCAG3′) et S15 (5′GGGCGGTGTGTACAAGGCC3′) [9] jusqu'en novembre 2011. A partir de décembre 2011, la spectrométrie de masse de type MALDI-TOF (Microflex, Brüker Daltonics) a été utilisée (bases de données DB 4613 et 5627). Une identification rétrospective par spectrométrie de masse a été réalisée pour les isolats initialement séquencés et conservés.

Traitement des prélèvements urinaires : un examen microscopique (coloration de Gram) était toujours réalisé en cas de leucocyturie significative (> 104/mL). Dix μL étaient systématiquement ensemencés sur une gélose chromogène incubée en aérobiose. Si l'examen microscopique ne montrait que des bacilles à Gram positif, une gélose au sang était également ensemencée sous atmosphère enrichie en CO2 pendant 48 heures.

Les observations cliniques de tous les cas ont été revues afin de déterminer le rôle pathogène de l'isolat. Les informations suivantes ont été recueillies : âge, sexe, facteurs de risques d'infection, site et circonstances d'isolement. Nous avons considéré qu'A. schaalii était pathogène lorsqu'il était clairement mentionné dans le compte rendu médical et/ou lorsqu'il s'agissait de la seule bactérie isolée dans le site infectieux.

Résultats

Entre juillet 2004 et février 2015, 24 isolats d'A. schaalii ont été isolés chez 24 patients. Six ont été identifiés par séquençage jusqu'en novembre 2011. Ensuite et jusqu'à février 2015, les 18 autres ont été identifiés par spectrométrie de masse. Parmi les 6 souches initialement identifiées par séquençage, 3 ont été identifiées par spectrométrie de masse. Les résultats des différents scores obtenus sont présentés dans le Tableau 1. Concernant les isolats identifiés par spectrométrie de masse, les moyennes statistiques des scores obtenus pour chacune des 3 premières identifications proposées sont présentées sur la Fig. 1

Tableau 1.

Identification rétrospective par spectrométrie de masse de 3 souches initialement identifiées par séquençage

| Isolat | 1er choix (score) | 2ème choix (score) | 3ème choix (score) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A. schaalii (2,03) | A. schaalii (2) | A. schaalii (1,8) |

| 2 | A. schaalii (2,15) | A. schaalii (1,75) | A. schaalii (1,63) |

| 3 | A. schaalii (1,93) | A. schaalii (1,57) | A. schaalii (1,54) |

Fig. 1.

Statistiques des scores (maximum, médiane, minimum) pour les 3 premières propositions (17 isolats)

.

Les circonstances d'isolement ainsi que les caractéristiques cliniques des patients sont résumés dans le Tableau 2. Les souches ont été isolées en majorité dans les abcès et collections (58% des cas, 14 isolats) : infections ostéo-articulaires et infections des parties molles dont kystes et divers abcès (paroi, sinus pilonidal, sein, malléole, …). Les urines correspondent à 33% des isolats : 8 cas dont 7 après novembre 2011 (Tableau 3). Enfin, les hémocultures représentent 8% des cas (2 isolats). Les urines et les hémocultures sont monomicrobiennes alors que 64% (9 cas sur 14) des abcès et collections sont plurimicrobiens.

Tableau 2.

Caractéristiques cliniques des patients

| Cas N° | Age/Sexe | Facteurs de risque | Nature du prélèvement | Autre(s) germe(s) | Imputabilité d'A. schaalii | Diagnostic retenu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58/F | Cancer | Hémoculture | Non | Non | Infection de PAC à S. epidermidis |

| 2 | 55/M | Gammapathie monoclonale | Hémoculture | Non | Non | Septicémie à E. cloacae |

| 3 | 8/M | Ectopie testiculaire, énurésie | Urine | Non | Oui | Infection urinaire |

| 4 | 81/M | Age, carcinome épidermoïde | Urine | Non | Oui | Infection urinaire |

| 5 | 83/F | Age, diabète | Urine | Non | Oui | Infection urinaire |

| 6 | 83/F | Age, colectomie, tumeur villeuse | Urine | Non | Oui | Infection urinaire |

| 7 | 96/F | Age, incontinence urino-fécale | Urine | Non | Oui | Infection urinaire |

| 8 | 75/F | Age | Urine | Non | Oui | Infection urinaire |

| 9 | 80/M | Age | Urine | Non | Oui | Infection urinaire |

| 10 | 66/M | Age | Urine | Non | Oui | Infection urinaire |

| 11 | 77/M | Age, diabète | Collection | Non | Oui | Ostéoarthrite |

| 12 | 23/M | Aucun | Collection | Non | Oui | Abcès de paroi abdominale |

| 13 | 69/M | Age | Collection | Non | Oui | Kyste sébacé surinfecté |

| 14 | 20/F | Aucun | Collection | Non | Oui | Abcès du sinus pilonidal |

| 15 | 34/F | Aucun | Collection | Non | Oui | Abcès du sein |

| 16 | 17/M | Aucun | Collection | Peptostreptococcus spp. | Non | Abcès de la malléole |

| 17 | 28/M | Aucun | Collection | P. mirabilis, K. pneumoniae, E. faecalis | Non | Collection du tibia gauche |

| 18 | 56/M | Diabète | Collection | Streptococcus spp., Peptostreptococcus spp. | Non | Kyste sébacé surinfecté |

| 19 | 74/F | Age | Collection | Actinomyces spp., Peptonophilus spp. | Non | Lipome surinfecté |

| 20 | 69/M | Age, diabète | Collection | Finegoldia spp., Anaerococcus spp. | Non | Mal perforant plantaire |

| 21 | 54/F | Diabète | Collection | Acinetobacter spp., Helcococcus spp., Anaerococcus spp. | Non | Abcès sur sternotomie |

| 22 | 77/M | Age | Collection | P. mirabilis, M. morganii | Non | Ostéite de la cheville |

| 23 | 27/F | Aucun | Collection | A. turisensis | Non | Abcès vaginal |

| 24 | 88/F | Age | Collection | S. aureus, F. magna, P. acnes | Non | Fistule de l'épaule |

Tableau 3.

Sites d'isolements d'A. schaalii, avant et après la mise en place de la spectrométrie de masse

| Urine | Abcès/collections | Hémocultures | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avant mise en place de la spectrométrie de masse | 1 | 5 | 0 | 6 |

| Après mise en place de la spectrométrie de masse | 7 | 9 | 2 | 18 |

Le sex ratio H/F des 24 patients est de 1,2 avec un âge moyen de 58,2 ans [8-96 ans]. Dans 75% des cas, au moins un facteur de risque d'infection est présent parmi les suivants : âge > 65 ans, immunodépression, anomalie du tractus génito-urinaire et diabète.

Discussion

L'introduction de la spectrométrie de masse en pratique quotidienne a conduit à une augmentation de la fréquence des isolats d'A. schaalii dans notre laboratoire (Tableau 3). En effet, entre juillet 2004 et novembre 2011, 6 souches d'A. schaalii avaient été identifiées par séquençage, versus 18 par spectrométrie de masse depuis novembre 2011. L'explication la plus probable est qu'avant novembre 2011, l'identification bactérienne de routine était effectuée par des tests biochimiques tels que les galeries API (bioMérieux) ou les cartes Vitek (bioMérieux). Ces techniques ne permettaient pas l'identification d'A. schaalii car il n'était alors pas présent dans les bases de données [10]; la dernière version 2015 de la carte Vitek ANC (bioMérieux) permet depuis peu sa détection. Concernant le séquençage, il était réalisé de manière exceptionnelle.

L'analyse des résultats d'identification obtenus par spectrométrie de masse (Fig. 1) montre que les 3 premières propositions correspondent bien aux 3 spectres d'A. schaalii de la base Brüker (Tableau 4) dans 17 cas sur 18, avec une médiane du score d'identification de 2,045 [1,82-2,26] pour la première proposition. Les 3 autres espèces du genre Actinobaculum présentes dans la base ne sont jamais proposées dans les identifications étudiées. De plus, la spectrométrie de masse rétrospective réalisée sur 3 isolats conservés et préalablement identifiés par séquençage de l'ADN ribosomal 16S donne de bons résultats d'identification. Comme décrit précédemment [10], nous avons confirmé les performances d'identification par MALDI-TOF Microflex (Brüker Daltonics) pour A. schaalii sur les 3 souches également identifiées par séquençage. En revanche, il est rapporté que le MALDI-TOF Vitek MS (BioMérieux) ne permet pas à l'heure actuelle l'identification d'A. schaalii [11], [12].

Tableau 4.

Base de notre spectromètre de masse (Brüker Daltonics) pour les Actinobaculum spp.

| Actinobaculum schaalii 70710715001 MVC |

| Actinobaculum schaalii DSM 15541T DSM |

| Actinobaculum schaalii RV_BA1_032010_E LBK |

| Actinobaculum suis DSM 20639T DSM |

| Actinobaculum suis GD75 GDD |

| Actinobaculum urinale DSM 15805T DSM |

Le rôle pathogène d'A. schaalii n'a pas été retenu par les cliniciens pour les 2 bactériémies de notre étude car un autre pathogène reconnu avait été isolé de plusieurs hémocultures pour chacun des 2 patients. De plus, la présence de ce germe appartenant au microbiote uro-génital en tant que contaminant des hémocultures suggère une possible présence au niveau cutané [6]. Néanmoins, nous ne pouvons exclure sa participation dans l'infection.

Les prélèvements urinaires présentent tous une leucocyturie significative (> 104/mL), un examen microscopique direct positif avec des bacilles à Gram positif et une culture monomicrobienne > 105 UFC/mL. L'isolement dans les urines nécessite un ensemencement sur une gélose au sang en atmosphère enrichie en CO2. Ceci est systématiquement réalisé dans notre laboratoire, sur les urines avec leucocyturie > 104/mL et des bacilles à Gram positif à l'examen microscopique. Les données cliniques recueillies concordent avec un tableau d'infection du tractus uro-génital. A. schaalii est donc responsable d'infection urinaire dans les 8 cas présentés. Un ou plusieurs facteurs de risque sont retrouvés chez ces patients, ce qui souligne le caractère opportuniste du germe. L'âge avancé est un de ces facteurs de risque (7 patients sur 8 avec un âge > 65 ans) d'infection urinaire à A. schaalii. Néanmoins, les infections chez les sujets jeunes ne sont pas à exclure [13], comme en témoigne le cas de pyélonéphrite aiguë chez un patient de 8 ans rapporté dans notre série.

Les résultats sont toutefois à confronter avec la clinique, car il ne faut pas oublier qu'il peut parfois s'agir d'un commensalisme urinaire. A ce titre, une étude prospective danoise a montré qu'A. schaalii pouvait être détecté par PCR dans les urines chez plus de 22% des patients d'un âge supérieur à 60 ans, malgré l'absence de signes cliniques dans certains cas [14]. Ceci peut expliquer qu'A. schaalii soit souvent rapporté au sein d'urines polymicrobiennes [15]. Dans notre pratique, lorsqu'il y a un uropathogène dominant, les autres bactéries éventuellement associées ne sont pas toujours identifiées, étant considérées comme des commensales.

Pour les abcès et les collections, nous distinguons les prélèvements mono- et plurimicrobiens. L'imputabilité est discutable pour les prélèvements avec plusieurs germes. Elle est plus facile lorsqu'il n'y pas d'autres bactéries associées. C'est le cas de la patiente de 34 ans avec un abcès de sein récidivant, chez qui A. schaalii a été clairement incriminé, comme précisé dans le compte rendu médical. Comme dans la majorité des cas que nous avons décrits, le traitement a été uniquement chirurgical avec des suites favorables, suggérant que contrairement aux infections urinaires, un traitement antibiotique n'est pas systématiquement requis pour traiter l'infection. Nous pouvons souligner que comparée aux isolats urinaires, la dispersion des âges des patients est plus importante pour les abcès et les collections. Une autre différence est que des patients jeunes sans facteurs de risque sont concernés : abcès de paroi abdominale chez un patient de 23 ans, abcès de sinus pilonidal chez un homme de 20 ans ou encore un abcès de sein observé chez une patiente de 34 ans. Il a toutefois été suggéré qu'A. schaalii pourrait contribuer au processus infectieux même quand il est isolé en présence d'autres germes [15]. Nous pouvons rappeler qu'un cas d'endocardite [16], une gangrène de Fournier [17], une spondylodiscite [18] et un urosepsis [19] ont ainsi déjà été rapportés, ce qui souligne le potentiel invasif de ce germe.

Au total, bien que les infections du tractus urinaire soient les plus fréquemment rapportées dans la littérature [12], notre étude montre que l'isolement d'A. schaalii dans les abcès et collections est fréquent. La fréquence d'isolement a augmenté depuis l'apparition de la spectrométrie de masse dans notre laboratoire. Cela suggère que le caractère émergent des infections dues à A. schaalii est probablement imputable aux lacunes des méthodes d'identification dans la microbiologie quotidienne avant l'ère de la spectrométrie de masse.

Conclusion

En conclusion, notre étude souligne une nouvelle fois l'apport de la spectrométrie de masse dans l'identification d'A. schaalii. Moins fastidieuse et moins coûteuse que la biologie moléculaire, elle remplace avantageusement les tests biochimiques pour l'identification de ce germe. L'émergence de cette bactérie vient donc vraisemblablement en partie d'une évolution dans les méthodes d'identification. Ceci va permettre une meilleure compréhension de l'épidémiologie des infections à A. schaalii. Le rôle pathogène est quant à lui discutable dans certains cas. D'autres études sont ainsi nécessaires, notamment sur l'habitat cutané et la virulence de cette bactérie, pour mieux interpréter sa présence dans un prélèvement, en particulier lorsqu'il est plurimicrobien.

Conflits d'intérêt

aucun

Remerciements

Nous remercions Madame Brigitte Couzon pour sa contribution technique.

Références

- 1.Lawson P.A., Falsen E., Akervall E., Vandamme P., Collins M.D. Characterization of some Actinomyces-like isolates from human clinical specimens: reclassification of Actinomyces suis (Soltys and Spratling) as Actinobaculum suis comb. nov. and description of Actinobaculum schaalii sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. juill 1997;47(3):899–903. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-3-899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker R.L., MacLachlan N.J. Isolation of Eubacterium suis from sows with cystitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 15 oct 1989;195(8):1104–1107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamini B., Slocombe R.F. Porcine abortion caused by Actinomyces suis. Vet Pathol. juill 1988;25(4):323–324. doi: 10.1177/030098588802500415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fendukly F., Osterman B. Isolation of Actinobaculum schaalii and Actinobaculum urinale from a patient with chronic renal failure. J Clin Microbiol. juill 2005;43(7):3567–3569. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3567-3569.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yassin A.F., Spröer C., Pukall R., Sylvester M., Siering C., Schumann P. Dissection of the genus Actinobaculum: Reclassification of Actinobaculum schaalii Lawson et al. 1997 and Actinobaculum urinale Hall et al. 2003 as Actinotignum schaalii gen. nov., comb. nov. and Actinotignum urinale comb. nov., description of Actinotignum sanguinis sp. nov. and emended descriptions of the genus Actinobaculum and Actinobaculum suis; and re-examination of the culture deposited as Actinobaculum massiliense CCUG 47753T ( = DSM 19118T), revealing that it does not represent a strain of this species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. févr 2015;65(Pt 2):615–624. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.069294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsen A.B., Andersen P.K., Bank S., Søby K.M., Lund L., Prag J. Actinobaculum schaalii, a commensal of the urogenital area. BJU Int. août 2013;112(3):394–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bank S., Jensen A., Hansen T.M., Søby K.M., Prag J. Actinobaculum schaalii, a common uropathogen in elderly patients, Denmark. Emerg Infect Dis. janv 2010;16(1):76–80. doi: 10.3201/eid1601.090761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nielsen H.L., Søby K.M., Christensen J.J., Prag J. Actinobaculum schaalii: a common cause of urinary tract infection in the elderly population. Bacteriological and clinical characteristics. Scand J Infect Dis. 2010;42(1):43–47. doi: 10.3109/00365540903289662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bercot B., Kannengiesser C., Oudin C., Grandchamp B., Sanson-le Pors M.-J., Mouly S. First description of NOD2 variant associated with defective neutrophil responses in a woman with granulomatous mastitis related to corynebacteria. J Clin Microbiol. sept 2009;47(9):3034–3037. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00561-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuuminen T., Suomala P., Harju I. Actinobaculum schaalii: identification with MALDI-TOF. New Microbes New Infect. mars 2014;2(2):38–41. doi: 10.1002/2052-2975.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Brun C., Robert S., Bruyere F., Lanotte P. Emerging uropathogens: Point for urologists and biologists. Prog En Urol J Assoc Fr Urol Société Fr Urol. juin 2015;25(7):363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2015.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cattoir V. Actinobaculum schaalii: review of an emerging uropathogen. J Infect. mars 2012;64(3):260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen L.B., Bank S., Hertz B., Søby K.M., Prag J. Actinobaculum schaalii, a cause of urinary tract infections in children? Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992. mai 2012;101(5):e232–e234. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bank S., Hansen T.M., Søby K.M., Lund L., Prag J. Actinobaculum schaalii in urological patients, screened with real-time polymerase chain reaction. Scand J Urol Nephrol. déc 2011;45(6):406–410. doi: 10.3109/00365599.2011.599333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tschudin-Sutter S., Frei R., Weisser M., Goldenberger D., Widmer A.F. Actinobaculum schaalii – invasive pathogen or innocent bystander? A retrospective observational study. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:289. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoenigl M., Leitner E., Valentin T., Zarfel G., Salzer H.J.F., Krause R. Endocarditis caused by Actinobaculum schaalii, Austria. Emerg Infect Dis. juill 2010;16(7):1171–1173. doi: 10.3201/eid1607.100349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanden Bempt I., Van Trappen S., Cleenwerck I., De Vos P., Camps K., Celens A. Actinobaculum schaalii causing Fournier's gangrene. J Clin Microbiol. juin 2011;49(6):2369–2371. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00272-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haller P., Bruderer T., Schaeren S., Laifer G., Frei R., Battegay M. Vertebral osteomyelitis caused by Actinobaculum schaalii: a difficult-to-diagnose and potentially invasive uropathogen. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol. sept 2007;26(9):667–670. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0345-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Brun C., Robert S., Bruyere F., Tanchoux C., Lanotte P. Urinary tract infection caused by Actinobaculum schaalii: a urosepsis pathogen that should not be underestimated. JMM Case Rep. 1 avr 2015;2(2) [Google Scholar]