Abstract

Electron deficient nitroaromatic compounds such as BTZ043 and its closest congener, PBTZ169, and related agents are a promising new class of anti-TB compounds. Herein we report the design and syntheses of 1,3-benzothiazinone azide (BTZ-N3) and related click chemistry products based on the molecular mode of activation of BTZ043. Our computational docking studies indicate that BTZ-N3 binds in the essentially same pocket as that of BTZ043. Detailed biochemical studies with cell envelope enzyme fractions of Mycobacterium smegmatis combined with our model biochemical reactivity studies with nucleophiles indicated that, in contrast to BTZ043, the azide analogue may have a different mode of activation for anti-TB activity. Subsequent enzymatic studies with recombinant DprE1 from Mtb followed by MIC determination in NTB1 strain of Mtb (harboring Cys387Ser mutation in DprE1 and is BTZ043 resistant) unequivocally indicated that BTZ-N3 is an effective reversible and noncovalent inhibitor of DprE1.

Keywords: BTZ043; DprE1; BTZ-N3; 1,3-Benzothiazinone azide; Mycobacterium smegmatis; Mycobacterium tuberculosis; tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is a disease mainly caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). Besides Mtb, other TB-causing mycobacteria include Mycobacterium africanum, Mycobacterium bovis, Mycobacterium canetti, Mycobacterium caprae, Mycobacterium microti, Mycobacterium mungi, and Mycobacterium pinnipedii. Together these mycobacteria are referred as the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC).1 The complete sequencing of the Mtb genome was completed more than 10 years ago.2,3 Concurrently, the past decade has seen major progress in the understanding of TB and, as a result, several therapeutic leads have been identified to help contain the infection. Recently, TMC207 (bedaquiline) was the first new anti-TB agent to be approved in over 40 years.4 However, TB still remains persistently prevalent, resulting in approximately two million deaths every year.5 The emergence of multidrug resistant (MDR), extensive drug resistant (XDR) and, recently, totally drug resistant strains further emphasizes the desperate, growing need for new anti-TB agents.

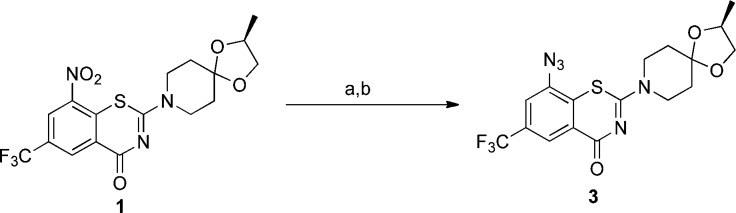

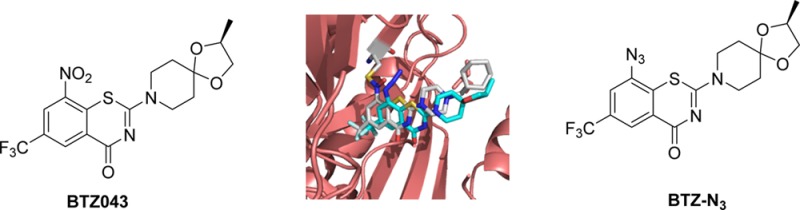

The discovery of 1,3-benzothiazin-4-ones (BTZs), especially BTZ043 (1, Figure 1)6 as a potent agent for the treatment of tuberculosis, led to the identification of several other classes of nitroaromatic compounds as anti-TB agents. BTZ0436 and its closest congener, PBTZ1697 (2), and analogues have been shown to kill Mtb in vitro, ex vivo, and in mouse models of TB. Both of these agents were shown to be suicide inhibitors of DprE1, a key enzyme of the cell wall assembly for mycobacteria.

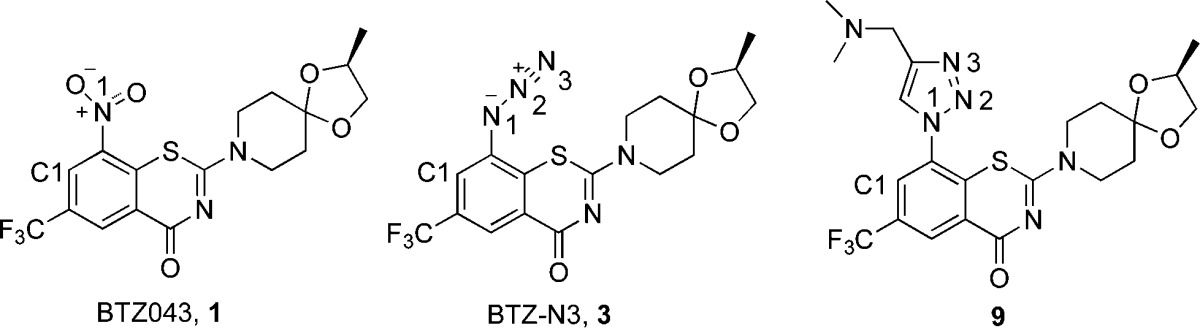

Figure 1.

Structures of 1,3-benzothiazinone anti-TB agents, BTZ043 (1), PBTZ169 (2), and BTZ-N3 (3).

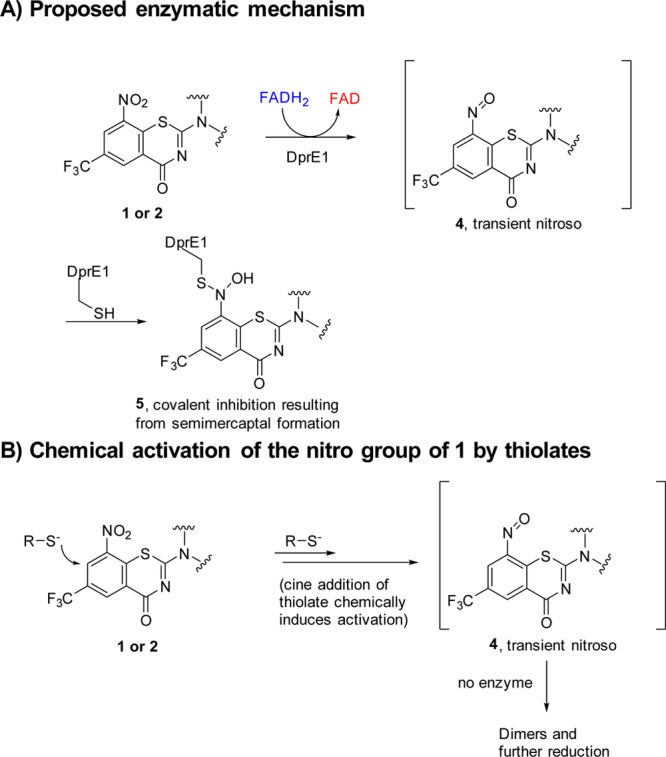

The detailed mode of suicide inhibition by 1 and 2 was elucidated, and it was shown to involve the reductive activation of the nitro group into a nitroso intermediate apparently aided by the hydride from FADH2 (see Figure 2A, compound 4), resulting in further covalent inactivation of DprE1 as a semimercaptal adduct (Figure 2A, structure 5).8,9 The detailed mechanistic and proteomics studies carried out by Makarov and Trefzer et al.6,8,9 have shown that the cysteine at the active site is essential for the anti-TB activity of 1 and 2 and its mutation to any other amino acid resulted in the dramatic loss of activity. Our efforts related to the mechanistic understanding of the reductive activation of 1 suggest that 1 and other related nitroaromatic anti-TB agents may undergo chemical activation of the constituent nitro group to the nitroso intermediate by a cine addition reaction (Figure 2B). Therefore, cine addition of either thiolate from the active site cysteine of DprE1 or hydride from a cofactor FADH2 may be responsible for the generation of the nitroso intermediate at the enzyme active site.10 It should be noted that in the absence of the enzyme, such nitroso intermediates, undergo dimerization or subsequent reduction (s) to hydroxylamines and amines.10

Figure 2.

Proposed enzymatic and chemical activation of the nitro group of BTZs leading to the covalent inhibition of DprE1.

We envisioned that the substitution of the nitro group of the 1,3-benzothiazinone scaffold by an electron withdrawing azide group (3, Figure 1) could result in a similar mode of activation and/or inhibition because the first nucleophilic step of a cine addition by either the thiolate from the essential cysteine or hydride from FADH2 would still occur similar to that shown in Figure 2B.10 However, in the case with an azide group, the formation of the nitroso derived “semimercaptal adduct” would not be possible and activity might depend on subsequent alternative chemistry. Additionally, recent studies identified “non-nitroaromatic” hits that bind to the same pocket as BTZ043 without formation of the covalent semimercaptal adduct.11 Therefore, synthesis and evaluation of the anti-TB activity of 3 was of interest and is reported herein.

Azide 3 was synthesized in two steps from 1 by first reducing the nitro group of the latter using Fe/CH3COOH under reflux conditions (120 °C) for 2 h to give the reduced amine 6. The amino group of 6 was subsequently treated with tert-butyl nitrite (t-BuONO) followed by azidotrimethylsilane (TMSN3)12 to afford 3 in good yield over two steps (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of BTZ-N3.

Reagent and conditions: (a) Fe, CH3COOH, 120 °C, 2 h, 87%; (b) t-BuONO, TMSN3, 30 min, 62%.

To explore and compare the binding of 3 with that of 1 at the active site of DprE1, both 3 and 1 were docked into the crystal structure of DprE1 (PDB # 4NCR)7 using Autodock Vina.13 Because 2 was crystallized as a covalent adduct with DprE1, the optimization of the docking protocol was achieved as described in the Supporting Information (SI). Briefly, the benzothiazinone ligand (semimercaptal) present in the crystal structure was deleted and no hydrogen was added to the formed thiolate of cys 387. The docking protocol was optimized by the redocking of the hydroxylamine form of pBTZ169 into the active site (see SI, Figure S1).

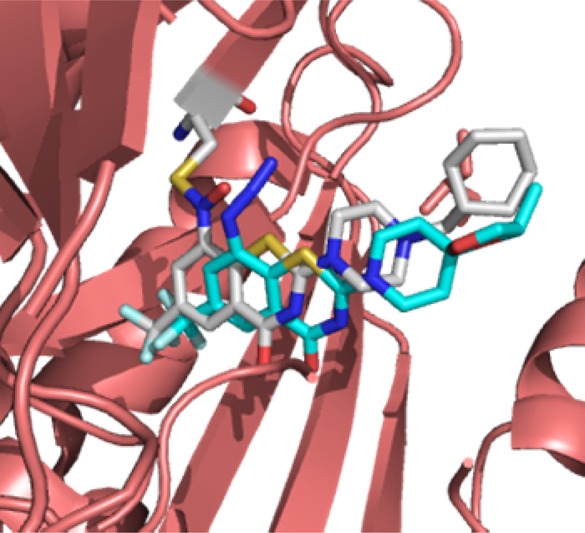

Next, we repeated the docking with BTZ-N3 to explore its binding. Our docking study indicated that it binds essentially in the same binding pocket as that of 2 (Figure 3). This docking provided further incentive to evaluate 3 in anti-TB assays.

Figure 3.

Overlay of the docked pose of 3 on the semimercaptal adduct of 2 with DprE1. The carbons of 2 are colored in white, whereas carbons of 3 are in cyan.

The in vitro activity of azide 3 in two different mycobacterial growth media (7H12 and GAS)14−16 is summarized in Table 1. The corresponding activity of BTZ043 (1) is also shown in Table 1 for comparison.

Table 1. In Vitro Activity of Azide 3, Amine 6, Desazido BTZ, 8, and Click Chemistry Products 9–11 and Controls against H37Rv Strain of Mtb (in 7H12 and GAS Media)a.

| compd | MABA:MIC 7H12 (μM) | MABA:MIC GAS(μM) | MIC NTB1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.5 |

| 6b | >10 (12%) | >10 (10%) | |

| 8 | >100 | 8.68 | |

| 9 | 0.87 | 0.95 | |

| 10c | 9.90 | 9.27 | |

| 11d | 0.93 | >1 | |

| 1 (BTZ043) | <0.004 | < 0.004 | |

| rifampin | 0.05 | 0.04 |

MABA, microplate alamar blue assay; GAS, glycerol-alanine-salts medium; 7H12, 7H9 medium plus casitone, palmitic acid, albumin, and catalase.

87% and 0% inhibition was observed at a concentration of >1 μM for 7H12 and GAS media, respectively.

0% inhibition was observed at >1 μM concentration for both 7H12 and GAS media.

34% inhibition was observed at >1 μM concentration for GAS media. NTB1, Mtb strain with Cys387Ser mutation.

As can be seen from Table 1, azide 3 showed excellent activity against the H37Rv strain of Mtb, albeit not as outstanding as BTZ043 itself. Similar to our earlier studies of the mechanistic chemistry of BTZ04310 and because of the similarity in electronic features to that of 1, we decided to determine the possible cine reactivity of azide 3 with nucleophiles. Mulliken charges17 calculated by semiempirical AM1 method18 (see Table 2) indicated that, in contrast to BTZ043, azide 3 has two highly electrophilic sites, namely the cine position (see Table 2, C1) and the terminal nitrogen of the azide group (see Table 2, N3).

Table 2. Mulliken Charges for Compounds 1, 3, and 9a.

| Mulliken charges | 1 | 3 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.09 |

| N1 | 0.57 | –0.23 | –0.14 |

| N2 | NA | 0.22 | 0.01 |

| N3 | NA | –0.01 | –0.05 |

The Mulliken charges are only shown for the numbered atoms for comparison.

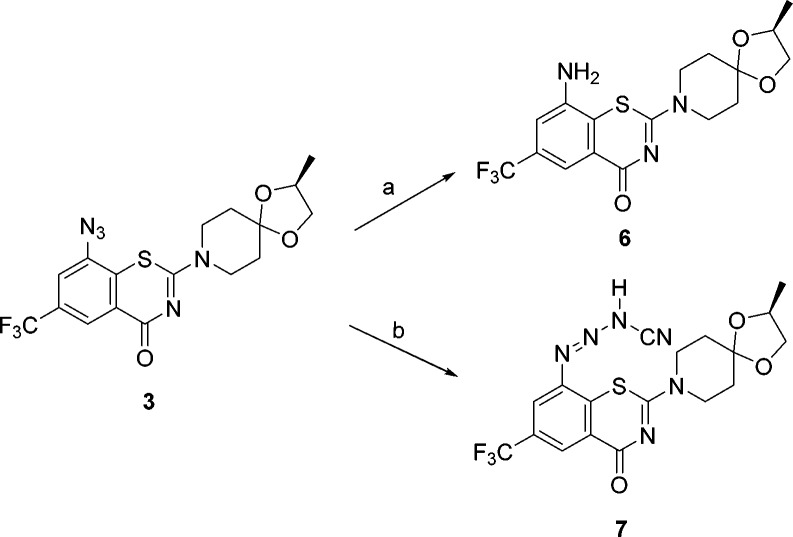

To probe further, we subjected 3 to reactions with sodium methanethiolate (NaSMe) and potassium cyanide (KCN) in acetonitrile/water (Scheme 2). Interestingly, the reaction of 3 with NaSMe did result in rapid net reduction of the azide to an amine (see SI). Although mechanistic details have not yet been elucidated, the reactivity is consistent with its anti-TB activity.

Scheme 2. Reactivity of BTZ-N3 with a Thiolate and Cyanide.

Reagents and conditions: (a) NaSMe, CH3CN/H2O; (b) KCN, CH3CN/H2O.

Our earlier studies of the reaction of BTZ043 with other nucleophiles, including cyanide, were also consistent with cine addition chemistry. However, while reaction of azide 3 with cyanide was clean and facile, the product obtained (cyanotriazene, 7) resulted from nucleophilic addition at the terminal nitrogen of the azide. A low resolution X-ray structure confirmed that the nucleophilic cyanide did not attack at the C1 carbon (see Table 2 for the numbering). Recall that BTZ043 and other nitrobenzamides have been shown to undergo nucleophilic attack at the C1 position by cyanides, resulting in the formation of bicyclic or tricyclic ring systems.10 This indicates that, although azide 3 has a 1,3-benzothiazinone scaffold, it might, however, undergo a somewhat different reaction (mode of activation) at the active site of DprE1.

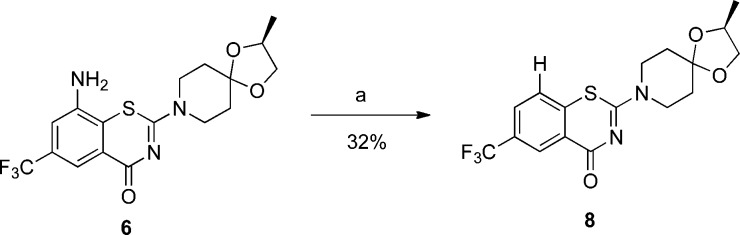

To confirm that the observed anti-TB activity of BTZ-N3 (3) was due to the combination of both the azide functionality and the benzothiazinone scaffold, we synthesized the corresponding “desazido-BTZ-N3” (8) as a control molecule. As shown in Scheme 3, amine 6 was treated with tert-butyl nitrite in THF for 30 min to give 8 in 32% yield after purification. However, as predicted, unlike its predecessors BTZ-N3 or BTZ043, 8 was notably less active against H37Rv strain of Mtb (Table 1).

Scheme 3. Synthesis of “Desazido-BTZ-N3”.

Reagent and conditions: (a) t-BuONO, THF, 30 min.

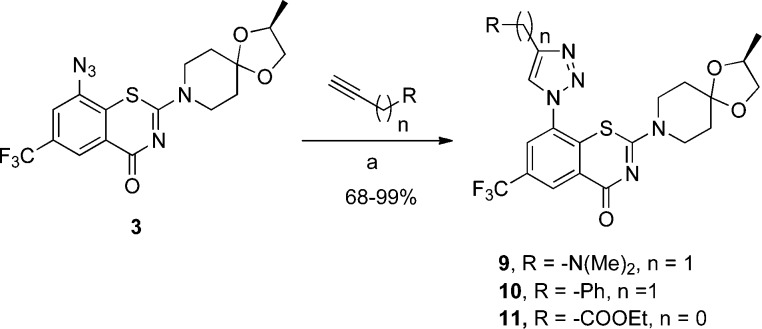

The availability of benzothiazinone azide 3 afforded an opportunity to synthesize and evaluate click chemistry19 reaction products. Therefore, 3 was treated with N,N-dimethylpropargylamine, phenylpropyne, and ethylpropiolate as representative alkynes under standard reaction conditions (Scheme 4) to give triazoles 9, 10, and 11, respectively, in 68–99% yields.

Scheme 4. Click Reactions of BTZ-N3.

Reagent and conditions: (a) CuSO4 5H2O, sodium ascorbate, tert-butanol/water.

As now expected, the substitution of the nitro or azido group by triazole functionality led to a decrease in the electron deficiency of the 1,3-benzothiazinone ring. This was also verified by Mulliken charge calculations (Table 2). Interestingly while the anti-TB activity of the triazoles was diminished relative to 1 and 3, as expected, it was still notable, especially for triazole 9 (Table 2). A docking study carried out with 9 as a representative triazole indicated that the whole scaffold is positioned further away from the binding pocket (see SI, Figure S2).

To investigate if the anti-TB activity of 3 was indeed due to inhibition of DprE1, compounds 3, 8, and BTZ043, as a control, were tested in the enzymatic assay with membrane and cell envelope fractions prepared from M. smegmatis.20,21 These were incubated with 14C-radiolabeled phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PRPP), which serves as a precursor of decaprenylphosphoryl arabinose (see SI for the detailed assay procedure).

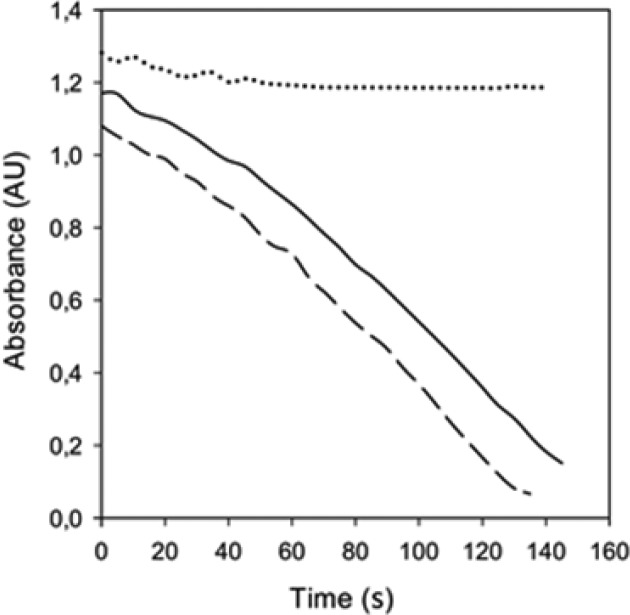

However, while BTZ043 efficiently inhibited conversion of decaprenylphosphoryl ribose to decaprenylphosphoryl arabinose through its interaction with DprE1 enzyme, as expected, compounds 3 and 8 did not show any effects on synthesis of decaprenylphosphoryl arabinose (see SI, Figure S3). This experiment along with the distinct chemical reactivity of 3 with cyanide as a nucleophile hints that, unlike BTZ043, 3 may not be a covalent inhibitor of DprE1 and may either inhibit DprE1 by noncovalent mechanism or has a different target. To address this difference, 3 was also assayed against the recombinant DprE1, prepared as previously reported,22 demonstrating that it is an effective DprE1 inhibitor, with an IC50 of 9.6 ± 0.5 μM (see SI). Moreover, to demonstrate that the inhibition is reversible, 3 was incubated with recombinant DprE1 in the presence of farnesylphosphoryl-β-d-ribofuranose (FPR) as substrate according to the previously published procedure (see SI for details).22 After the incubation, determination of residual enzymatic activity conclusively indicated that, while BTZ043 led to an irreversible inhibition of DprE1, in vitro compound 3 reversibly inhibited the enzyme (Figure 4). Additionally, the MIC value of 3 was determined in the NTB1 strain (Cys387Ser mutation in DprE1)23,24 that was shown to be resistant to BTZ043. Here also, 3 was found to be an effective inhibitor (Table 1), indicating that it is a reversible and noncovalent inhibitor of DprE1 (see SI).

Figure 4.

Measurements of the enzymatic activity of DprE1 after preincubation with FPR and compound 3 (solid line), BTZ043 (dotted line), or DMSO as control (dashed line), demonstrating the noncovalent inhibition mechanism of 3.

In conclusion, BTZ-azide 3 has impressive activity against TB. The significantly reduced activity of the des-azido compound 8 and moderated activity of triazole click products 9–11 again emphasize that electronically activating functional groups (such as NO2, or N3) promote anti-TB activity of the 1,3-benzothiazinones. The biological activity of BTZ-N3 combined with the chemical reactivity described in Scheme 2 indicates that BTZ-N3 might have alternative modes of reactivity with DprE1. Indeed, additional biochemical and enzymatic studies substantiated our hypothesis that, while BTZ043 is a covalent inhibitor of DprE1, BTZ-azide is an efficient reversible and noncovalent inhibitor. The studies described here indicate that the BTZ scaffold may provide still further opportunities for development of much needed new anti-TB agents.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grant 2R01AI054193 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). We thank the University of Notre Dame, especially the Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Facility (Bill Boggess, Michelle Joyce, and Nonka Sevova), which is supported by grant CHE-0741793 from the National Science Foundation (NSF). K.M. received support from the European Community’s 7th Framework Programme (MM4TB, grant 260872) and the Slovak Research and Development Agency (contract no. DO7RP-0015-11)

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- DprE1

decaprenylphosphoryl-β-d-ribose 2′ oxidase

- MDR

multidrug resistant

- M tuberculosis

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- XDR

extensively drug resistant

- TB

tuberculosis

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00424.

Syntheses and characterization data for the reported compounds, overlay of the docked poses of 9 and 2, study of compounds 3 and 8 with cell envelope enzyme fractions of M. smegmatis, detailed enzymatic study of BTZ-N3 with recombinant DprE1 with H37Rv and NTB1 strain of Mtb, 1H and 13C NMR spectra of the synthesized compounds, reaction of 3 with NaSMe resulting in the formation of 6 (PDF)

Author Contributions

R.T. designed, synthesized the compounds and carried out all mechanistic studies the docking studies and wrote the manuscript. P.A.M., S.C.. and S.G.F. did the biological screening in non-pathologic and pathological mycobacteria. L.R.C. and G.M. carried out enzymatic studies with recombinant DprE1. M.S., I.C., and K.M. carried out the enzymatic assays with membrane and cell envelope fractions of M. smegmatis. A.G.O. analyzed the low resolution X-ray structure of 7. M.J.M. conceived of and originated the project, directed studies, wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to editing the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Rastogi N.; Legrand E.; Sola C. The mycobacteria: an introduction to nomenclature and pathogenesis. Rev. Sci. Technol. 2001, 20, 21–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole S. T.; Brosch R.; Parkhill J.; Garnier T.; Churcher C.; Harris D.; Gordon S. V.; Eiglmeier K.; Gas S.; Barry C. E.; Tekaia F.; Badcock K.; Basham D.; Brown D.; Chillingworth T.; Connor R.; Davies R.; Devlin K.; Feltwell T.; Gentles S.; Hamlin N.; Holroyd S.; Hornsby T.; Jagels K.; Krogh A.; McLean J.; Moule S.; Murphy L.; Oliver K.; Osborne J.; Quail M. A.; Rajandream M. A.; Rogers J.; Rutter S.; Seeger K.; Skelton J.; Squares R.; Squares S.; Sulston J. E.; Taylor K.; Whitehead S.; Barrell B. G. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 1998, 393, 537–544. 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann R. D.; Alland D.; Eisen J. A.; Carpenter L.; White O.; Peterson J.; DeBoy R.; Dodson R.; Gwinn M.; Haft D.; Hickey E.; Kolonay J. F.; Nelson W. C.; Umayam L. A.; Ermolaeva M.; Salzberg S. L.; Delcher A.; Utterback T.; Weidman J.; Khouri H.; Gill J.; Mikula A.; Bishai W.; Jacobs J. W. R.; Venter J. C.; Fraser C. M. Whole-Genome Comparison of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Clinical and Laboratory Strains. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 5479–5490. 10.1128/JB.184.19.5479-5490.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diacon A. H.; Pym A.; Grobusch M.; Patientia R.; Rustomjee R.; Page-Shipp L.; Pistorius C.; Krause R.; Bogoshi M.; Churchyard G.; Venter A.; Allen J.; Palomino J. C.; De Marez T.; van Heeswijk R. P. G.; Lounis N.; Meyvisch P.; Verbeeck J.; Parys W.; de Beule K.; Andries K.; Neeley D. F. M. The Diarylquinoline TMC207 for Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 2397–2405. 10.1056/NEJMoa0808427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumla A.; Nahid P.; Cole S. T. Advances in the development of new tuberculosis drugs and treatment regimens. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2013, 12, 388–404. 10.1038/nrd4001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarov V.; Manina G.; Mikusova K.; Möllmann U.; Ryabova O.; Saint-Joanis B.; Dhar N.; Pasca M. R.; Buroni S.; Lucarelli A. P.; Milano A.; De Rossi E.; Belanova M.; Bobovska A.; Dianiskova P.; Kordulakova J.; Sala C.; Fullam E.; Schneider P.; McKinney J. D.; Brodin P.; Christophe T.; Waddell S.; Butcher P.; Albrethsen J.; Rosenkrands I.; Brosch R.; Nandi V.; Bharath S.; Gaonkar S.; Shandil R. K.; Balasubramanian V.; Balganesh T.; Tyagi S.; Grosset J.; Riccardi G.; Cole S. T. Benzothiazinones kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis by blocking arabinan synthesis. Science 2009, 324, 801–804. 10.1126/science.1171583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarov V.; Lechartier B.; Zhang M.; Neres J.; van der Sar A. M.; Raadsen S. A.; Hartkoorn R. C.; Ryabova O. B.; Vocat A.; Decosterd L. A.; Widmer N.; Buclin T.; Bitter W.; Andries K.; Pojer F.; Dyson P. J.; Cole S. T. Towards a new combination therapy for tuberculosis with next generation benzothiazinones. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014, 6, 372–383. 10.1002/emmm.201303575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trefzer C.; Rengifo-Gonzalez M.; Hinner M. J.; Schneider P.; Makarov V.; Cole S. T.; Johnsson K. Benzothiazinones: prodrugs that covalently modify the decaprenylphosphoryl-beta-D-ribose 2′-epimerase DprE1 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 13663–13665. 10.1021/ja106357w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trefzer C.; Skovierova H.; Buroni S.; Bobovska A.; Nenci S.; Molteni E.; Pojer F.; Pasca M. R.; Makarov V.; Cole S. T.; Riccardi G.; Mikusova K.; Johnsson K. Benzothiazinones are suicide inhibitors of mycobacterial decaprenylphosphoryl-beta-D-ribofuranose 2′-oxidase DprE1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 912–915. 10.1021/ja211042r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari R.; Moraski G. C.; Krchnak V.; Miller P. A.; Colon-Martinez M.; Herrero E.; Oliver A. G.; Miller M. J. Thiolates chemically induce redox activation of BTZ043 and related potent nitroaromatic anti-tuberculosis agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 3539–3549. 10.1021/ja311058q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.; Sambandan D.; Halder R.; Wang J.; Batt S. M.; Weinrick B.; Ahmad I.; Yang P.; Zhang Y.; Kim J.; Hassani M.; Huszar S.; Trefzer C.; Ma Z.; Kaneko T.; Mdluli K. E.; Franzblau S.; Chatterjee A. K.; Johnsson K.; Mikusova K.; Besra G. S.; Futterer K.; Robbins S. H.; Barnes S. W.; Walker J. R.; Jacobs W. R. Jr.; Schultz P. G. Identification of a small molecule with activity against drug-resistant and persistent tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, E2510–2517. 10.1073/pnas.1309171110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barral K.; Moorhouse A. D.; Moses J. E. Efficient conversion of aromatic amines into azides: a one-pot synthesis of triazole linkages. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 1809–1811. 10.1021/ol070527h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O.; Olson A. J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S. H.; Warit S.; Wan B.; Hwang C. H.; Pauli G. F.; Franzblau S. G. Low-oxygen-recovery assay for high-throughput screening of compounds against nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 1380–1385. 10.1128/AAC.00055-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins L.; Franzblau S. G. Microplate alamar blue assay versus BACTEC 460 system for high-throughput screening of compounds against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997, 41, 1004–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Voss J. J.; Rutter K.; Schroeder B. G.; Su H.; Zhu Y.; Barry C. E. 3rd The salicylate-derived mycobactin siderophores of Mycobacterium tuberculosis are essential for growth in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000, 97, 1252–1257. 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulliken R. S. Electronic population analysis on LCAO-MO [linear combination of atomic orbital-molecular orbital] molecular wave functions. I. J. Chem. Phys. 1955, 23, 1833–1840. 10.1063/1.1740588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dewar M. J. S.; Zoebisch E. G.; Healy E. F.; Stewart J. J. P. Development and use of quantum mechanical molecular models. 76. AM1: A new general purpose quantum mechanical molecular model. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 3902–3909. 10.1021/ja00299a024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H. C.; Finn M. G.; Sharpless K. B. Click Chemistry: Diverse Chemical Function from a Few Good Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2004–2021. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikusova K.; Huang H.; Yagi T.; Holsters M.; Vereecke D.; D’Haeze W.; Scherman M. S.; Brennan P. J.; McNeil M. R.; Crick D. C. Decaprenylphosphoryl arabinofuranose, the donor of the D-arabinofuranosyl residues of mycobacterial arabinan, is formed via a two-step epimerization of decaprenylphosphoryl ribose. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 8020–8025. 10.1128/JB.187.23.8020-8025.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherman M. S.; Kalbe-Bournonville L.; Bush D.; Xin Y.; Deng L.; McNeil M. Polyprenylphosphate-pentoses in mycobacteria are synthesized from 5-phosphoribose pyrophosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 29652–29658. 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neres J.; Hartkoorn R. C.; Chiarelli L. R.; Gadupudi R.; Pasca M. R.; Mori G.; Venturelli A.; Savina S.; Makarov V.; Kolly G. S.; Molteni E.; Binda C.; Dhar N.; Ferrari S.; Brodin P.; Delorme V.; Landry V.; de Jesus Lopes Ribeiro A. L.; Farina D.; Saxena P.; Pojer F.; Carta A.; Luciani R.; Porta A.; Zanoni G.; De Rossi E.; Costi M. P.; Riccardi G.; Cole S. T. 2-Carboxyquinoxalines kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis through noncovalent inhibition of DprE1. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 705–714. 10.1021/cb5007163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirude P. S.; Shandil R. K.; Manjunatha M. R.; Sadler C.; Panda M.; Panduga V.; Reddy J.; Saralaya R.; Nanduri R.; Ambady A.; Ravishankar S.; Sambandamurthy V. K.; Humnabadkar V.; Jena L. K.; Suresh R. S.; Srivastava A.; Prabhakar K. R.; Whiteaker J.; McLaughlin R. E.; Sharma S.; Cooper C. B.; Mdluli K.; Butler S.; Iyer P. S.; Narayanan S.; Chatterji M. Lead optimization of 1,4-azaindoles as antimycobacterial agents. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 5728–5737. 10.1021/jm500571f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda M.; Ramachandran S.; Ramachandran V.; Shirude P. S.; Humnabadkar V.; Nagalapur K.; Sharma S.; Kaur P.; Guptha S.; Narayan A.; Mahadevaswamy J.; Ambady A.; Hegde N.; Rudrapatna S. S.; Hosagrahara V. P.; Sambandamurthy V. K.; Raichurkar A. Discovery of pyrazolopyridones as a novel class of noncovalent DprE1 inhibitor with potent anti-mycobacterial activity. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 4761–4771. 10.1021/jm5002937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.