Abstract

To identify G protein-biased and highly subtype-selective EP2 receptor agonists, a series of bicyclic prostaglandin analogues were designed and synthesized. Structural hybridization of EP2/4 dual agonist 5 and prostacyclin analogue 6, followed by simplification of the ω chain enabled us to discover novel EP2 agonists with a unique prostacyclin-like scaffold. Further optimization of the ω chain was performed to improve EP2 agonist activity and subtype selectivity. Phenoxy derivative 18a showed potent agonist activity and excellent subtype selectivity. Furthermore, a series of compounds were identified as G protein-biased EP2 receptor agonists. These are the first examples of biased ligands of prostanoid receptors.

Keywords: Prostaglandin, EP2, agonist, biased ligand, structure−functional selectivity relationship

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is an oxidative metabolite of arachidonic acid that exerts a wide variety of biological actions through four receptor subtypes, EP1–EP4, in various tissues. The EP2 receptor has been characterized by relaxation of blood vessels.1 Furthermore, EP2 receptor plays important roles in cytokine production and bone metabolism.2,3 It has also been reported that activation of EP2 receptor led to neuroprotective effects in ischemic stroke models.4−8 EP2 receptor receives a lot of attention as a therapeutic target for various diseases.

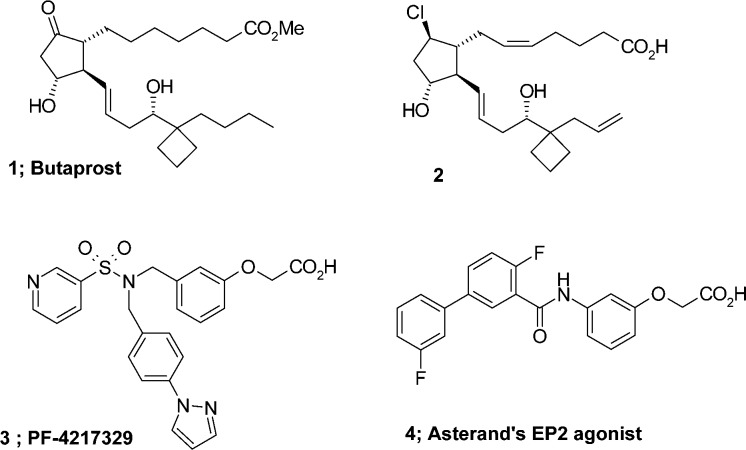

A number of EP2 agonists have previously been reported.9−15 The PGE2 analogue, butaprost (1), is well-known as a selective EP2 agonist and is widely used as a chemical tool compound in many studies on pharmacological activities mediated by EP2 receptor (Figure 1). In previous studies, we developed the highly selective and chemically stable EP2 agonist, 2,10 which is a good tool compound for EP2 receptor. A number of nonprostanoid scaffolds of EP2 agonists have also been reported to show potent EP2 agonist activity (for example, PF-4217329 3(13) and 4(15)). In recent studies by Pfizer, PF-4217329 3, an isopropyl ester, showed remarkable intraocular pressure lowering effects in primary open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension.16 To date, however, there is no EP2 agonist that is approved for clinical use. Although the true reasons for the suspension of clinical trials of EP2 agonists are not clear, we assume that a variety of biological actions induced by EP2 agonists caused crucial side effects for clinical use.

Figure 1.

Reported EP2 agonists.

Recently, biased ligands have received a fair amount of attention in drug discovery17−22 because they have the potential to suppress on-target adverse effects and enhance efficacy. In addition to G protein signaling, G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) can activate other distinct signaling pathways, like β arrestin-mediated signaling. GPCR-biased ligands are compounds that selectively stimulate either G protein or β arrestin pathways. A number of studies have been performed to investigate the biological roles of G protein- and β arrestin-mediated EP2 receptor signaling. In the brain, EP2 receptor modulates beneficial neuroprotective effects in acute models of excitotoxicity through G protein-mediated cAMP-PKA signaling.4,5,23,24 Conversely, activation of β arrestin-mediated EP2 receptor signaling led to deleterious effects, like tumorigenesis and angiogenesis.25−27 Therefore, we hypothesized that G protein-biased ligands of EP2 receptor have the potential to be next generation EP2 agonists that will overcome the clinical problems of previously reported EP2 agonists.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no report of biased ligands of prostanoid receptors. Moreover, we performed screening of our in-house EP2 agonists and failed to identify G protein-biased agonists. As the compounds we evaluated have a similar structure to PGE2, we aimed to discover G protein-biased EP2 agonists by design and investigation of a new scaffold. In this report, we describe our discovery of novel, highly selective EP2 agonists with a unique bicyclic scaffold, which were identified as G protein-biased EP2 agonists. The functional selectivity and signaling bias of the compounds are also discussed.

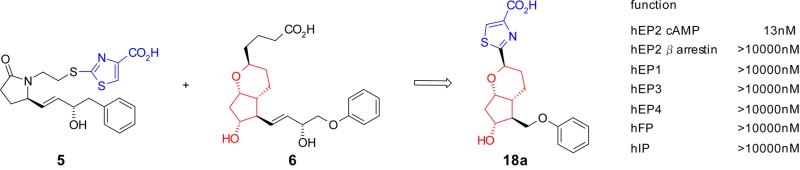

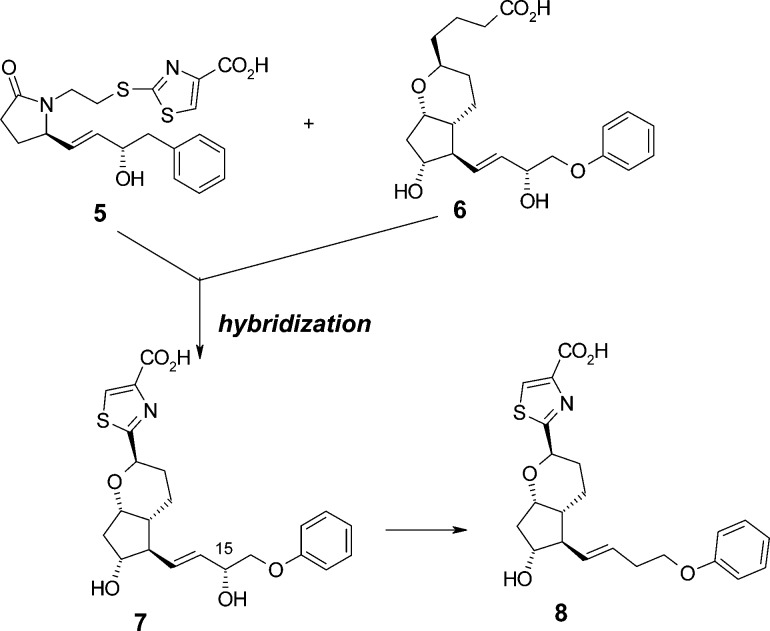

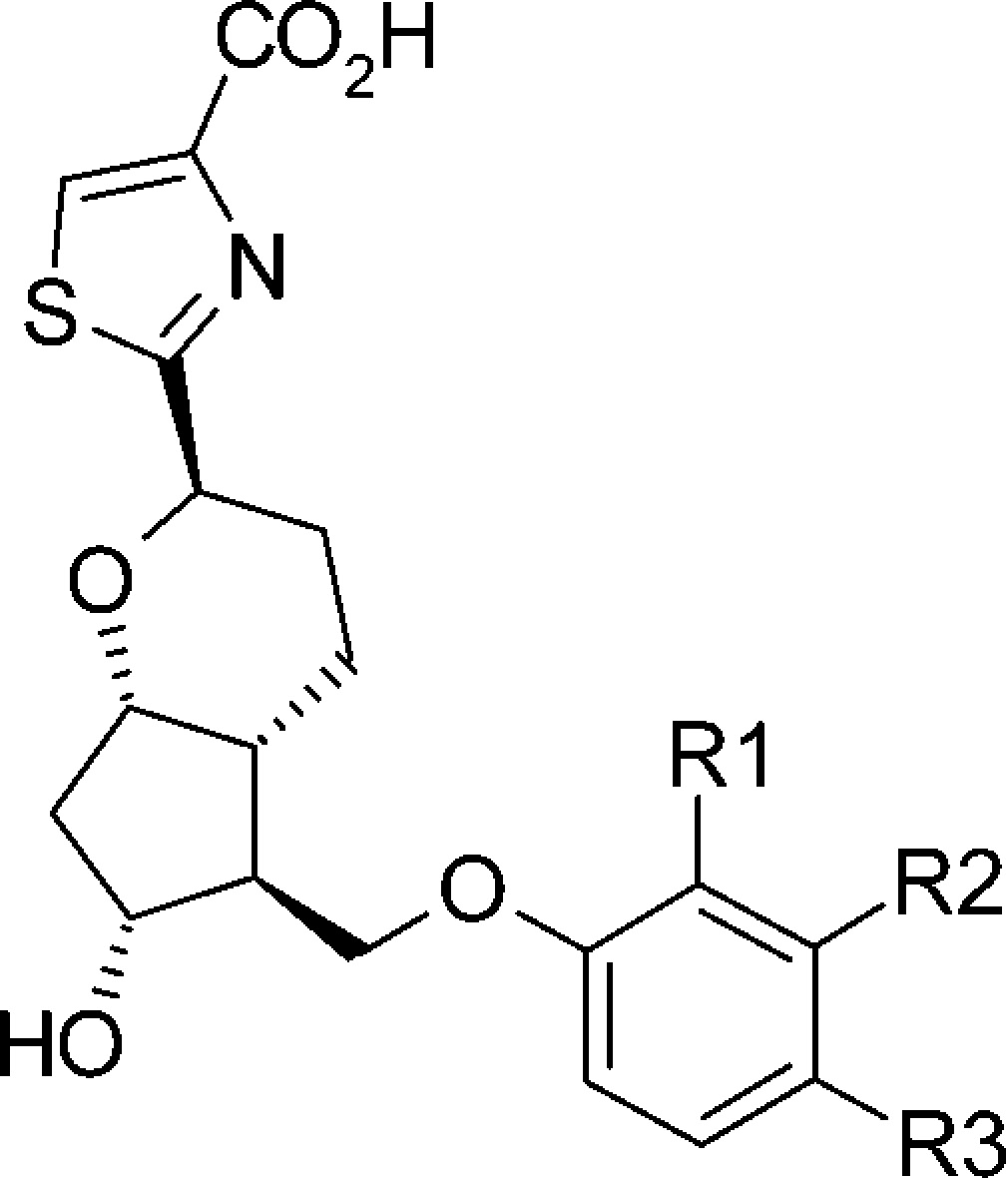

First, to identify novel subtype selective EP2 agonists with a new scaffold, we focused on EP2/EP4 dual agonist 5. In our previous study,28 a thiazole group of 5 was one of the key substructures to increase EP2 agonist activity. Introduction of a thiazole group into various reported scaffolds seemed to contribute to the development of novel and potent EP2 agonists. Chemically stable prostacyclin analogue 6,29 which has been reported by the Upjohn group in the 1970s, showed very weak EP2 agonist activity (EC50 = 8900 nM). We designed and synthesized compound 7 with a bicyclic scaffold by hybridization of 6 and the thiazole moiety of 5 (Figure 2). The resulting 7 exhibited remarkably potent EP2 agonist activity as we expected, however, it also showed potent agonist activity toward the other receptor subtypes, especially EP1 and EP3 (Table 1). To increase the subtype selectivity, we next focused on the ω chain of 7.

Figure 2.

Design of novel EP2 agonists with unique bicyclic scaffold.

Table 1. Subtype Selectivity of Initial Lead Compounds.

| EC50 (nM)a |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cmpd | hEP1 | hEP2 | hEP3 | hEP4 | hFP | hIP |

| 5 | N.T.b | 5.6 | 3000 | 0.5 | N.T. | N.T. |

| 6 | N.T. | 8900 | N.T. | 4600 | N.T. | 47 |

| 7 | 1.4 | 7.9 | 0.8 | 33 | 32 | 11 |

| 8 | 160 | 3.9 | 260 | 1900 | 380 | 2500 |

Assay protocols are provided in the Supporting Information. EC50 values represent the mean of two experiments.

N.T.: Not tested.

Because all the natural prostanoids (for example, PGE2, PGI2, and PGF2α) have a hydroxyl group at a particular position in the ω chain, the hydroxyl group is supposed to be a crucial moiety for exerting agonist activity toward PG receptors. However, a number of nonprostanoid scaffolds of EP2 agonists without a hydroxyl group have been reported to show potent EP2 agonist activity (for example, 3(13) and 4(15)). We hypothesized that removal of the 15-hydroxyl group from compound 7 would be effective for decreasing the agonist activity toward all of the receptor subtypes except for EP2. As expected, the dehydroxylated derivative 8 dramatically improved the subtype selectivity without any loss of EP2 agonist activity. As a result of the preliminary modification, compound 8 was identified as an initial lead compound that is a highly selective EP2 agonist.

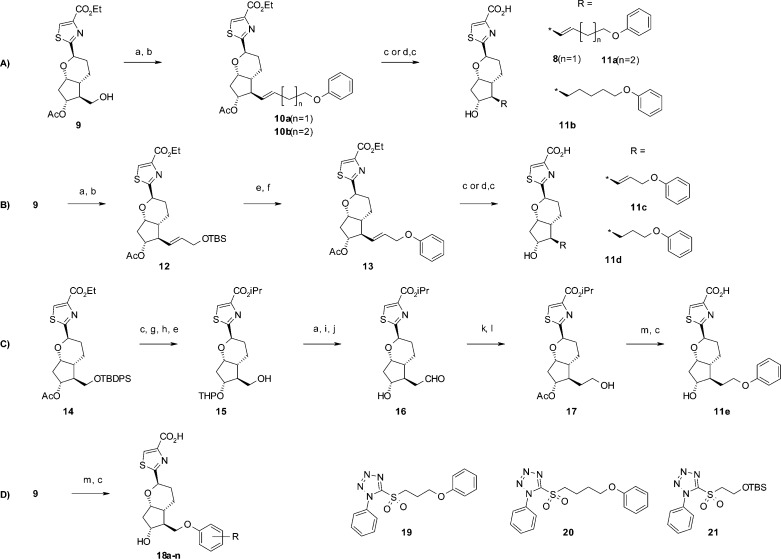

All test compounds in Tables 1–3 were synthesized as outlined in Schemes 1.

Table 3. Structure–Functional Selectivity Relationship Study of Phenoxy Derivatives.

| hEP2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

G protein (cAMP) |

β

arrestin |

|||||

| cmpd | R1 | R2 | R3 | EC50 (nM)a | Emax (%)b | EC50 (nM)a | Emax (%) |

| prostaglandin E2 | 1.9 | 105 | 346 | 107 | |||

| 18a | H | H | H | 13 | 118 | >10,000 | 28 |

| 18b | Cl | H | H | 3.3 | 95 | 203 | 78 |

| 18c | CF3 | H | H | 0.5 | 119 | 11 | 121 |

| 18d | F | H | H | 23 | 59 | >10,000 | 38 |

| 18e | H | Me | H | 3.6 | 100 | >10,000 | 38 |

| 18f | H | Cl | H | 6.5 | 65 | >10,000 | 27 |

| 18g | H | OCF3 | H | 0.9 | 119 | 69 | 79 |

| 18h | H | CF3 | H | 0.9 | 112 | 9 | 62 |

| 18i | H | F | H | 5.4 | 94 | >10,000 | 35 |

| 18j | H | H | Me | 27 | 85 | >10,000 | 20 |

| 18kc | H | H | Cl | 3.9 | 96 | >10,000 | 12 |

| 18l | H | H | OCF3 | 14 | 110 | 4500 | 57 |

| 18m | H | H | CF3 | 13 | 103 | >10,000 | 23 |

| 18n | H | H | F | 7 | 99 | >10,000 | 22 |

Assay protocols are provided in the Supporting Information. EC50 values represent the mean of two experiments.

All Emax were normalized to PGE2 results.

Concentration–response data is shown in Figure S2 (Supporting Information).

Scheme 1. Syntheses of Compounds 8, 11a–e, and 18a–n.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Dess–Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 77%; (b) 19, 20, or 21, KHMDS, DME, 0 °C, 18–66%; (c) 2 mol/L NaOHaq, DME, MeOH, rt, 56–96%; (d) TsNHNH2, NaOAc, EtOH, H2O, 80 °C, 55–71%, (e) TBAF, THF, rt, 96%; (f) DEAD, Ph3P, THF, rt, 82%; (g) i-PrI, K2CO3, DMF, rt, 54%; (h) PPTS, CH2Cl2, DHP, rt; (i) (methoxymethyl)triphenylphospine chrolide, KOtBu, THF, rt, 64%; (j) TsOH, acetone, H2O, rt, 78%; (k) Ac2O, Py, rt, 82%; (l) NaBH4, THF, rt, 61%; (m) phenol analogues, TMAD, Bu3P, THF, rt, 61–92%. Syntheses of common intermediate 9 and Julia–Kocienski reagents 19–21 are shown in the Supporting Information.

Syntheses of compounds 8 and 11a,b are outlined in Scheme 1A. Oxidation of the common intermediate 9, followed by the Julia–Kocienski reaction with reagent 19 or 20 gave compound 10a or 10b. Hydrolysis provided compounds 8 and 11a. Reduction of the double bond of 10b, followed by hydrolysis gave compound 11b.

Syntheses of compounds 11c,d are outlined in Scheme 1B. Oxidation of the common intermediate 9, followed by the Julia–Kocienski reaction using reagent 21 gave compound 12. Deprotection of the TBS group, followed by a Mitsunobu reaction gave compound 13. Hydrolysis provided compound 11c. Reduction of the double bond of 13 and hydrolysis gave compound 11d.

Synthesis of compound 11e is outlined in Scheme 1C. Hydrolysis of 14, esterification and protection of the hydroxyl group by a THP moiety, followed by deprotection of the TBDPS gave alcohol 15. The resulting alcohol 15 was treated with Dess–Martin reagent to give an aldehyde, which was transformed to a vinyl ether by treatment with a phosphoylide. Acidic hydrolysis of the vinyl ether gave compound 16. Acetylation of the hydroxy group, followed by reduction of the aldehyde gave compound 17. Introduction of a phenoxy group by the Mitsunobu reaction and hydrolysis provided compound 11e.

Syntheses of compounds 18a–n were started from commercially available phenols as outlined in Scheme 1D. Phenol was introduced into 9 by the Mitsunobu reaction, and the product was hydrolyzed under basic conditions to give 18a. Compounds 18b–n were synthesized in a similar manner using the corresponding phenols.

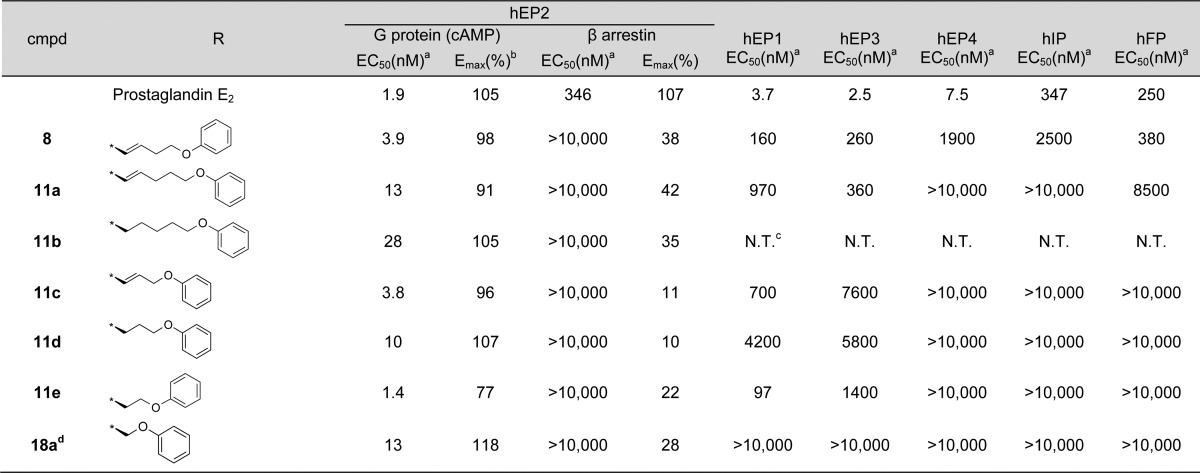

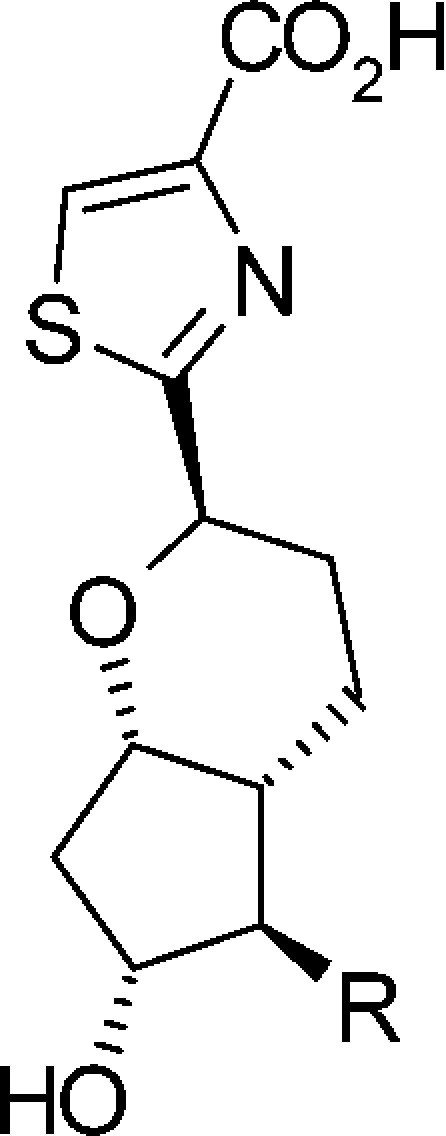

Chemical modification of the ω chain was performed to further improve subtype selectivity of the initial lead compound 8. As described in Table 2, 11a–e and 18a were synthesized to adjust the length between the cyclopentane scaffold and the phenoxy moiety, and to investigate the effect of the double bond of the ω chain.

Table 2. Optimization of the ω Chain for Functional and Subtype Selectivity.

Assay protocols are provided in the Supporting Information. EC50 values represent the mean of two experiments.

All Emax were normalized to PGE2 results.

N.T.; Not tested.

Concentration–response data is shown in Figure S2 (Supporting Information).

Compound 11a, which has a longer linker relative to 8, demonstrated improved subtype selectivity to EP4 and FP receptors, while it showed a 3.3-fold decreased EP2 agonist activity. Conversely, 11c with a shorter linker relative to 8 showed potent EP2 agonist activity and improved subtype selectivity. Reduction of the double bond of 11a and 11c gave 11b and 11d with 2.2- and 2.6-fold decreases in EP2 agonist activity, respectively. Compound 11e, with a shorter linker relative to 11c, showed the most potent EP2 agonist activity; however, it also had a potent EP1 agonist activity. The shortest ω chain derivative 18a exhibited an excellent selectivity to all other receptor subtypes with favorable G protein activity.

We next investigated the functional selectivity of the newly identified EP2 agonists 8, 11a–e, and 18a. The compounds were evaluated by the EP2-mediated β arrestin recruitment Path Hunter assay30 (DiscoveRX), to determine their functional selectivity. Surprisingly, none of the compounds exerted full agonist activity toward β arrestin recruitment at 10 μM, that is, these compounds were identified as G protein-biased EP2 agonists (see Table 2). To our knowledge, these are the first examples of biased ligands of prostanoid receptors.

To investigate the structure–functional selectivity relationship20 and improve G protein agonist activity, we performed further optimization of compound 18a. As demonstrated in Table 3 (18b–d), introduction of steric hindering substituents to the ortho position on the phenyl moiety improved the β arrestin activity, and the electron nature of the ortho substituents had a small effect on its functional selectivity. Introduction of 2-Cl substituent to the phenyl moiety afforded 18b, which showed a 3.9-fold increase in G protein activity, and it dramatically increased β arrestin recruitment. Compound 18c, which has a 2-CF3 substituent on the phenyl moiety, also increased the G protein activity and showed a more than 900-fold increase in β arrestin recruitment. Conversely, compound 18d, which possesses a 2-F substituent, showed a partial G protein activity without any change in β arrestin recruitment.

As shown in Table 3 (18e–i), introduction of meta substituents into the phenyl moiety generally improved G protein activity. Additionally, steric hindrance of meta substituents on the phenyl moiety significantly affected the functional selectivity, that is, bulky substituents enhanced β arrestin recruitment. Compound 18e, which possesses a 3-Me substituent on the phenyl moiety, was 3.6-fold more potent in G protein activity without increasing β arrestin activity. Introduction of a 3-Cl substituent gave 18f, which retained both G protein and β arrestin activity relative to 18a. However, introduction of 3-OCF3 and 3-CF3 substituents gave 18g and 18h, respectively, both of which showed a 14-fold increase in G protein activity compared with 18a. Additionally, 18g and 18h showed dramatically increased β arrestin activity (144-fold increase for 18g and 1111-fold increase for 18h). Compound 18i with a 3-F substituent retained both G protein and β arrestin activity relative to 18a.

Introduction of para substituents into the phenyl moiety had little effect on the functional selectivity, namely, all five substituent derivatives were found to be G protein-biased EP2 agonists (see Table3, 18j–n). Introduction of a 4-Me moiety (18j) slightly decreased G protein activity with no effect on β arrestin recruitment. 4-Cl derivative 18k showed a 3.3-fold more potent G protein activity without an increase in β arrestin activity. Compound 18l, possessing bulky substituents (OCF3) at the para position, showed moderate G protein activity and very weak β arrestin recruitment. In contrast to the ortho or meta position, introduction of a CF3 group into the para position of the phenyl moiety (18m) surprisingly lost the β arrestin activity. Compound 18n, possessing a less hindered fluoride at the para position, showed similar profiles to 18a.

Overall, steric hindrance of the ortho and meta positions on the phenyl moiety dramatically enhanced β arrestin recruitment and changed the functional selectivity, though the electron characteristics of the substituents did not show any significant difference in functional selectivity among the analogues. These structure–activity relationship studies suggest that the functional selectivity is easily controlled by small chemical modifications of the phenyl moiety.

To confirm the G protein-biased agonism of our EP2 agonists, lead compound 18a and 18k, which was the most potent G protein activity in para substituents derivatives, were evaluated in an equimolar comparison31 of G protein and β arrestin responses (see Figure S1 in Supporting Information). Both compounds showed markedly less β arrestin activity with equivalent G protein activity relative to PGE2, this result indicates 18a, and a series of compounds are G protein-biased agonists of EP2 receptor.

In summary, we designed a novel EP2 agonist 8 by hybridization of the thiazole moiety and the bicyclic scaffold mimicking prostacyclins. Simplification of the ω chain enabled us to discover the highly selective EP2 phenoxy derivative 18a, which was identified as a G protein-biased EP2 agonist. The substituents on the phenyl group of 18a play an important role in modulating the functional selectivity. Further optimization of phenoxy analogues, including the structure–functional selectivity relationship, will be performed in future studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr S. Nakayama for his efforts on the biological tests. We also thank Drs K. Ohmoto and R. Nishizawa and Mr. T. Karakawa for their helpful suggestions during the preparation of this article.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00455.

Experimental procedures of compounds, characterization data, and conditions of the biological assays (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Coleman R. A.; Kennedy I.; Humphrey P. P. A.; Bunce K.; Lumley P. In Comprehensive Medicinal Chemistry; Hansch C., Sammes P. G., Taylor J. B., Emmett J. C., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, 1990; Vol. 3, pp 643–714. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K.; Oida H.; Kobayashi T.; Maruyama T.; Tanaka M.; Katayama T.; Yamaguchi K.; Segi E.; Tsuboyama T.; Matsushita M.; Ito K.; Ito Y.; Sugimoto Y.; Ushikubi F.; Ohuchida S.; Kondo K.; Nakamura T.; Narumiya S. Stimulation of bone formation and prevention of bone loss by prostaglandin E EP4 receptor activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99, 4580–4585. 10.1073/pnas.062053399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuyama M.; Ikegami R.; Karahashi H.; Amano F.; Sugimoto Y.; Ichikawa A. Characterization of the LPS-stimulated expression of EP2 and EP4 prostaglandin E receptors in mouse macrophage-like cell line, J774.1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 251, 727–731. 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J.; Dingledine R. Prostaglandin receptor EP2 in the crosshairs of anti-inflammation, anti-cancer, and neuroprotection. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 34, 413–423. 10.1016/j.tips.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough L.; Wu L.; Haughey N.; Liang X.; Hand T.; Wang Q.; Breyer R. M.; Andreasson K. Neuroprotective function of the PGE2 EP2 receptor in cerebral ischemia. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 257–268. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4485-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D.; Wu L.; Breyer R.; Mattson M. P.; Andreasson K. Neuroprotection by the PGE2 EP2 receptor in permanent focal cerebral ischemia. Ann. Neurol. 2005, 57, 758–761. 10.1002/ana.20461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Liang X.; Wang Q.; Breyer R. M.; McCullough L.; Andreasson K. Misoprostol, an anti-ulcer agent and PGE2 receptor agonist, protects against cerebral ischemia. Neurosci. Lett. 2008, 438, 210–215. 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.04.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M.; Saleem S.; Shah Z.; Maruyama T.; Narumiya S.; Doré S. The PGE2 EP2 receptor and its selective activation are beneficial against ischemic stroke. Exp. Transl. Stroke Med. 2010, 2, 12. 10.1186/2040-7378-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron K. O.; Lefker B. A.; Ke H. Z.; Li M.; Zawistoski M. P.; Tjoa C. M.; Wright A. S.; DeNinno S. L.; Paralkar V. M.; Owen T. A.; Yu L.; Thompson D. D. Discovery of CP-533536: an EP2 receptor selective prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) agonist that induces local bone formation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 2075–2078. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani K.; Naganawa A.; Ishida A.; Egashira H.; Sagawa K.; Harada H.; Ogawa M.; Maruyama T.; Ohuchida S.; Nakai H.; Kondo K.; Toda M. Design and synthesis of a highly selective EP2-receptor agonist. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 2025–2028. 10.1016/S0960-894X(01)00359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner P. J. Characterization of prostanoid relaxant/inhibitory receptors (ψ) using a highly selective agonist, TR4979. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1986, 87, 45–56. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb10155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Old D. W.; Dinh D. T.. Substituted Gamma Lactams as Therapeutic Agents. Int. Pat. Appl. WO2006098918, 2006.

- Prasanna G.; Bosworth C. F.; Lafontaine J. A.. EP2 agonists. Int. Pat. Appl. WO2008015517, 2008.

- Hagihara M.; Yoneda K.; Okanari E.; Shigetomi M.. Parmaceutical composition for treating of preventing glaucoma. Int. Pat. Appl. WO2010113957, 2010.

- Coleman R.; Middlemiss D.. Difuluorophenylamide derivatives for the treatment of ocular hypertension. Int. Pat. Appl. WO2009098458, 2009.

- Prasanna G.; Carreiro S.; Anderson S.; Gukasyan H.; Sartnurak S.; Younis H.; Gale D.; Xiang C.; Wells P.; Dinh D.; Almaden C.; Fortner J.; Toris C.; Niesman M.; Lafontaine J.; Krauss A. Effect of PF-04217329 a prodrug of a selective prostaglandin EP(2) agonist on intraocular pressure in preclinical models of glaucoma. Exp. Eye Res. 2011, 93, 256–264. 10.1016/j.exer.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violin J. D.; Lefkowitz R. J. β-arrestin-biased ligands at seven-transmembrane receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2007, 28, 416–422. 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L.; Lovell K. M.; Frankowski K. J.; Slauson S. R.; Phillips A. M.; Streicher J. M.; Stahl E.; Schmid C. L.; Hodder P.; Madoux F.; Cameron M. D.; Prisinzano T. E.; Aubé J.; Bohn L. M. Development of functionally selective, small molecule agonists at kappa opioid receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 36703–36716. 10.1074/jbc.M113.504381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll C. C.; Mckittrick B. A. Biased ligand modulation of seven transmembrane receptors (7TMRs): functional implications for drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 6887–6896. 10.1021/jm401677g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Sassano M. F.; Zheng L.; Setola V.; Chen M.; Bai X.; Frye S. V.; Wetsel W. C.; Roth B. L.; Jin J. Structure-functional selectivity relationship studies of β-arrestin-biased dopamine D2 receptor agonists. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 7141–7153. 10.1021/jm300603y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. T.; Pitis P.; Liu G.; Yuan C.; Gotchev D.; Cowan C. L.; Rominger D. H.; Koblish M.; Dewire S. M.; Crombie A. L.; Violin J. D.; Yamashita D. S. Structure-activity relationships and discovery of a G protein biased μ opioid receptor ligand, [(3-methoxythiophen-2-yl)methyl]({2-[(9R)-9-(pyridin-2-yl)-6-oxaspiro-[4.5]decan-9-yl]ethyl})amine (TRV130), for the treatment of acute severe pain. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 8019–8031. 10.1021/jm4010829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violin J. D.; DeWire S. M.; Yamashita D.; Rominger D. H.; Nguyen L.; Schiller K.; Whalen E. J.; Gowen M.; Lark M. W. Selectively engaging β-Arrestins at the angiotensin II type 1 receptor reduces blood pressure and increases cardiac performance. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010, 335, 572–579. 10.1124/jpet.110.173005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilak M.; Wu L.; Wang Q.; Haughey N.; Conant K.; St. Hillaire C.; Andreasson K. PGE2 receptors rescue motor neurons in a model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2004, 56, 240–248. 10.1002/ana.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco E.; Werner P.; Casper D. Prostaglandin receptor EP2 protects dopaminergic neurons against 6-OHDA-mediated low oxidative stress. Neurosci. Lett. 2008, 441, 44–49. 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun K. S.; Lao H. C.; Trempus C. S.; Okada M.; Langenbach R. The prostaglandin receptor EP2 activates multiple signaling pathways and β-arrestin1 complex formation during mouse skin papilloma development. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 1620–1627. 10.1093/carcin/bgp168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun K. S.; Lao H. C.; Langenbach R. The prostaglandin E2 receptor, EP2, stimulates keratinocyte proliferation in mouse skin by G protein-dependent and β-arrestin1-dependent signaling pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 39672–39681. 10.1074/jbc.M110.117689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun S. P.; Ryu J. M.; Jang M. W.; Han H. J. Interaction of profilin-1 and F-actin via a β-arrestin-1/JNK signaling pathway involved in prostaglandin E2-induced human mesenchymal stem cells migration and proliferation. J. Cell. Physiol. 2011, 226, 559–571. 10.1002/jcp.22366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambe T.; Maruyama T.; Nakai Y.; Yoshida H.; Oida H.; Maruyama T.; Abe N.; Nishiura A.; Nakai H.; Toda M. Discovery of novel prostaglandin analogs as potent and selective EP2/EP4 dual agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 2235–2251. 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A. J.; Kalarmazoo M.. Enlarged-hetero-ring prostacyclin analogs. U.S. Patent US4490537, 1977.

- Path Hunter assay (DiscoveRX homepage). https://www.discoverx.com/arrestin (accessed Nov 12, 2015).

- Rajagopal S.; Ahn S.; Rominger D. H.; MacDonald W. G.; Lam C. M.; DeWire S. M.; Violin J. D.; Lefkowitz R. J. Quantifying Ligand Bias at Seven-Transmembrane Receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2011, 80, 367–377. 10.1124/mol.111.072801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.