Abstract

Importance

Advances in mobile technology have resulted in federal and industry-level initiatives to facilitate large-scale clinical research using smart devices. Although the benefits of technology to expand data collection are obvious, assumptions about the reach of mobile research methods (access), participant willingness to engage in mobile research protocols (engagement), and the cost of this research (cost) remain untested.

Objective

To assess the feasibility of a fully mobile randomised controlled trial using assessments and treatments delivered entirely through mobile devices to depressed individuals.

Design

Using a web-based research portal, adult participants with depression who also owned a smart device were screened, consented and randomised to 1 of 3 mental health apps for treatment. Assessments of self-reported mood and cognitive function were conducted at baseline, 4, 8 and 12 weeks. Physical and social activity was monitored daily using passively collected phone use data. All treatment and assessment tools were housed on each participant's smart phone or tablet.

Interventions

A cognitive training application, an application based on problem-solving therapy, and a mobile-sensing application promoting daily activities.

Results

Access: We screened 2923 people and enrolled 1098 participants in 5 months. The sample characteristics were comparable to the 2013 US census data. Recruitment via Craigslist.org yielded the largest sample. Engagement: Study engagement was high during the first 2 weeks of treatment, falling to 44% adherence by the 4th week. Cost: The total amount spent on for this project, including staff costs and β testing, was $314 264 over 2 years.

Conclusions and relevance

These findings suggest that mobile randomised control trials can recruit large numbers of participants in a short period of time and with minimal cost, but study engagement remains challenging.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Accessible, mHealth, Psychiatry

Introduction

Five hundred million individuals use mental health apps worldwide, with these numbers expected to reach 1.7 billion by 2018.1 The potential for mobile devices to revolutionise healthcare and clinical research has not been lost on either industry2 3 or academia.4–6 Notable examples of initiatives to collect behavioural data using mobile technology are the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)-funded Patient-Centered Clinical Outcomes Research Networks, National Institutes of Health (NIH's) Precision Medicine Initiative, and Apple's Research Kit. Indeed, the use of smart technology appears to be a clear avenue to increase research participation.7 8

Mobile technologies may be particularly useful in improving participant access to and reducing expenses of randomised clinical trials (RCTs). Typical RCTs cost millions of dollars and recruit 200–300 participants in 3–5 years.9 Sample demographics are determined by the location of the research institution, limiting the representativeness of many RCT samples. Expense and access problems are exacerbated when trying to study populations who are challenging to recruit, such as those with mental illnesses, people living in rural areas or racial/ethnic minority populations.

One solution to overcome access and cost issues has been the use of the internet to conduct randomised control studies. These trials are beneficial from the cost perspective, with estimated cost reductions of more than 50% compared with conventional trials,10 11 and from the access perspective, these studies recruit very large samples in short periods of time.12 13 However, retention issues are particularly problematic for internet studies, with one recent internet-based trial reporting a drop-out rate of over 90% in a sample of 3000 individuals.14 Drop-out is likely due in part to the need to access a WiFi connection and dependence on an immobile device (eg, a desktop computer). A potential advantage to research using mobile devices (smart phones and tablets) is that data can be collected anywhere at any time. These devices also facilitate passive data collection such as Global Positioning System (GPS) information from the phone's accelerometer and media usage to gauge social and physical activity that can supplement self-reports. However, while mobile technology may be able to further expand the reach of clinical research, this approach has yet to be tested.

The purpose of this study is to determine the feasibility of conducting a fully remote RCT using smart devices in depressed adults 18 years old and older. We elected to study depression as our clinical focus given its ubiquitous presence in mental illnesses and disability.15 It is the leading cause of disability worldwide,16 17 and the enrolment of depressed individuals into clinical trials is difficult.18 19 In this paper, we report data on population access (sample representativeness), engagement assessment and cost to complete the study.

Methods

Ethical approval for the trial was granted by the UCSF Committee for Human Research.

Recruitment

To test our hypotheses about access, we used three different types of recruitment approaches: traditional, social networking and search engine-based methods. Traditional methods were written ads placed in city buses, newspapers and Craigslist postings throughout the USA. Social networking methods included regular postings on sites such as Facebook and Twitter, and contextual-targeting methods to identify and directly push recruitment ads to potential participants, based on their Twitter and other social media comments. Our search engine-based method included using Google Adwords, a historically successful recruitment tool.20 Each approach (described further in see online supplementary materials) provided potentially interested participants a link to our custom study website (http://www.brightenstudy.com).

Participant eligibility

Participants had to speak English, be 18 years old or older, own a smartphone (iPhone or Android) with WiFi or 3G/4G capabilities, and own an iPad2 or newer device. iPad ownership was required as our cognitive assessment tool was only available on this device at the time of the study. To characterise recruiting logistics without this restriction, individuals without an iPad but with a smartphone were given the opportunity to participate in phone-only study arms that were not part of the randomised sample. A Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9),21 score of 5 or greater, or a score of 2 or greater on PHQ item 10 (indicating that they felt disabled in their life because of their mood), was also required for enrolment.

Procedure

Screening

Potential participants were directed to a website (http://www.brightenstudy.com) explaining the study purpose and procedures. Interested participants completed an online brief screening consisting of questions about mobile device ownership.

Consent

We used a combination of a written consent and custom videos posted on YouTube to explain the study. Participants had to pass a quiz that tested their understanding that the study was voluntary, was not a substitute for treatment and that they were to be randomised. Each question had to be answered correctly before moving on to baseline assessment and randomisation. Eligibility was established after consent was obtained.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised to one of three treatment arms where they viewed a brief video explaining how to download and use the assessment and assigned treatment app. Participants were also given a link to view a custom dashboard of their study progress.

Treatment

Participants were asked to use their assigned app for 1 month. The first app was a cognitive intervention video game (Project: EVO™, or EVO) designed to modulate cognitive control abilities, a common neurological deficit underlying depression.22 The second intervention was an app based on an evidence-based treatment for depression (problem-solving therapy, or PST).23 The final intervention app, an information control, provided daily health tips (HT) for overcoming depressed mood such as self-care (eg, taking a shower) or physical activity (eg, taking a walk; see online supplementary materials for further descriptions of each).

Assessment

We used two apps to collect baseline and 4, 8 and 12 weeks of outcome data. The first app, developed by Ginger.io™ was used to collect self-reported mood, function and passive analytics such as communication data (text logs including call/text time, call duration, text length and screen usage), and mobility data (activity type and distance travelled using the phone's accelerometer and GPS). The second app was a mobile cognitive assessment app (Adaptive Cognitive Evaluation (ACE)), to measure cognitive control processes (see online supplementary etable 1). Participants were automatically notified every 8 h for 24 h if they had not completed a survey within 8 h of its original delivery. An assessment was considered missing if it was not completed within this 24 h time frame.

The baseline assessment included the collection of demographics including age, race/ethnicity, martial and employment status, income, education, smart device ownership, use of other health apps, and use of mental health services, including use of medications and psychotherapy. We collected information on mental health status using the PHQ-924 for depression, the generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)-7,22 for generalised anxiety, a four-item mania and psychosis-screening instrument25 and the four-item National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Alcohol Screening Test.26 To assess for self-reported disability, we used the Sheehan Disability Scale.27 28 We also asked participants to rate their health on a scale of excellent to poor.

Daily assessments were a combination of self-report and passive data collection. Participants completed the PHQ-2 (mood and enjoyment) every morning. The Ginger.io app collected passive analytics daily. Private information such as actual content of voice calls or text messages or emails was not collected.

The 4-week, 8-week and 12-week assessments included the PHQ-9 to measure changes in mood, ACE for changes in cognitive control, and the Sheehan for changes in disability. Participants were also asked this question: ‘since using this app, I feel that I am: (1) much worse, (2) worse, (3) no different, (4) improved, (5) much improved’.

Payment

Randomised participants were paid a total of $75 for completing all assessments over the 12 weeks via Amazon gift vouchers, while participants in the phone-only arms were paid $45 as they did not complete the cognitive assessment. To test if increased payment led to increased adherence and retention, a subset of participants (n=144) were given $75 in bonus pay if they completed all assessments.

Procedures to reduce gaming

‘Gaming’ is a situation where a user fraudulently enrols in a study solely to acquire research payment. We utilised the following safeguards to prevent this: (1) locking the eligibility survey if a participant tried to change a submitted answer, (2) using study links that are valid for one user/device, and (3) tracking IP addresses to minimise duplicate enrolment.

Statistical analyses

To assess participant access, we describe the sample demographics, clinical characteristics and sample comorbidities using the appropriate descriptive statistics. To assess participant engagement, we examined the proportion of study drop-outs and the proportion of enrolled individuals who responded to the primary mood outcome measures at each time point using a mixed-model analysis of variance (with Greenhouse-Geisser corrections when needed). To calculate time to drop-out, we tested a survival analysis model with the distribution of the ‘survival’ times for those assigned each app estimated and non-parametric estimates of the survivor function computed by the Kaplan-Meier method, with curves tested using the log-rank test using Stata V.14.0. We also examined whether there was a significant difference in drop-out rates among the three interventions using Pearson's χ2 test. Pairwise log-rank tests were conducted to determine where there were significant differences between the distributions, and a Bonferroni correction was set at p<0.017 to correct for multiple comparisons. We also compared these outcomes for the entire sample and by sample type (randomised and non-randomised). To assess issues surrounding cost, we describe a total study cost approach factoring in β testing, staff time and efforts beyond those payments made for recruitment and participant remuneration.

Results

Access

Recruitment rate

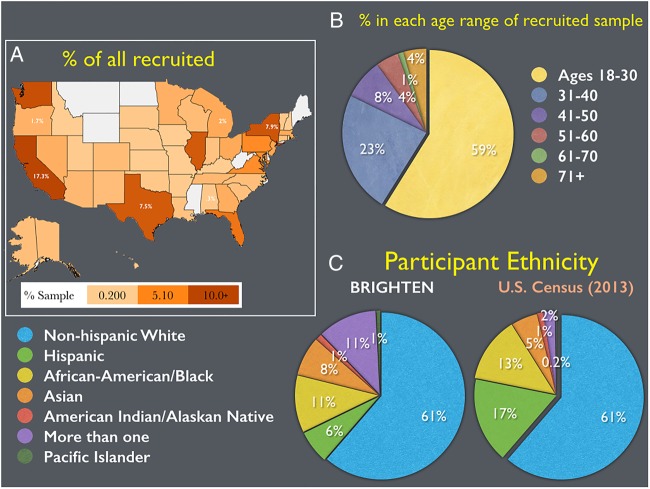

National recruitment began in August of 2014, and was conducted in five, 2-week advertising waves (total of 5 months of recruitment). We recruited a total of 2923 participants. Of these recruited individuals, 1098 were enrolled to the randomised (N=626) and non-randomised (N=472) arms of the study (see figure 1). Eighty-nine per cent of the sample came from traditional recruitment approaches, <1% came from social networking, <1% came from search engine-based methods, and 10.3% came from unanticipated means (own search, referrals). We were able to successfully recruit individuals from 8 of the 15 most rural states in the USA29 without any targeted recruitment efforts (see figure 2A).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram (HT, health tips; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire).

Figure 2.

Demographic characteristics. (A) Percentage of recruited participants across the USA. (B) Percentage of participants within different age ranges from the recruited sample. (C) Ethnic composition of the recruited individuals, and its comparison to the observed ethnic composition reported in the 2013 US Census.

Sample demographics

Participants were primarily young adults (see figure 2B), although age ranged from 18 to 76, with 79% identifying as female. Fifty-eight per cent of our sample was non-Hispanic white, and an ethnicity distribution comparable to the 2013 US Census (see figure 2C). Fifty-seven per cent of our participants obtained a 4-year college degree or higher, with a mean annual income of $30–$35 000 (see table 1). Sixty-seven per cent of our participants were employed at the time of enrolment. There was a difference in age between randomised and phone-only assigned participants, with randomised participants slightly older than phone-only participants, t(954.38)=−3.22, p=0.001. However, there was no difference in gender between these groups ( =0.08, p=0.77). Enrolled individuals who were single/never married reported greater symptoms of depression (t[528.17]=2.96, p=0.003).

=0.08, p=0.77). Enrolled individuals who were single/never married reported greater symptoms of depression (t[528.17]=2.96, p=0.003).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics

| Variable | PST | EVO (iPad) | HT (iPad) | EVO (iPhone) | HT (Android) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 34.91 (12.33) | 33.37 (10.87) | 33.56 (12.27) | 30.33 (11.11) | 32.41 (10.26) |

| Education | |||||

| <12 years | 39 (18.48) | 31 (14.83) | 36 (17.48) | 52 (21.85) | 77 (32.91) |

| College | 133 (63.03) | 129 (61.72) | 122 (59.22) | 148 (62.18) | 125 (53.42) |

| Graduate | 39 (18.48) | 49 (23.44) | 49 (23.30) | 38 (15.97) | 32 (13.68) |

| Income+ | |||||

| $20 000 or less | 42 (35.00) | 31 (35.23) | 39 (31.71) | 73 (53.28) | 79 (58.96) |

| $20 000–$40 000 | 32 (26.67) | 21 (23.86) | 30 (24.39) | 37 (27.01) | 34 (25.37) |

| $40 000–$60 000 | 26 (21.67) | 17 (19.32) | 17 (13.82) | 18 (13.14) | 14 (10.45) |

| $60 000–$80 000 | 6 (5.00) | 9 (10.23) | 18 (14.63) | 7 (5.11) | 4 (2.99) |

| $80 000–$100 000 | 6 (5.00) | 3 (3.41) | 7 (5.69) | 1 (0.73) | 1 (0.75) |

| $100 000+ | 8 (6.67) | 7 (7.95) | 12 (9.76) | 1 (0.73) | 2 (1.49) |

| Number of females | 160 (75.83) | 161 (77.03) | 173 (83.98) | 198 (83.19) | 172 (73.50) |

| Per cent of minority | 83 (39.34) | 87 (41.63) | 82 (39.81) | 94 (39.50) | 110 (47.01) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 118 (55.92) | 112 (53.59) | 118 (57.28) | 164 (68.91) | 150 (64.10) |

| Married | 62 (29.38) | 73 (34.93) | 68 (33.01) | 53 (22.27) | 53 (22.65) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 31 (14.69) | 24 (11.48) | 20 (9.71) | 21 (8.82) | 31 (13.25) |

| Psychiatric | |||||

| PHQ-9 | 13.76 (4.91) | 13.51 (5.06) | 13.64 (4.90) | 13.61 (5.02) | 15.01 (5.23) |

| GAD | 10.36 (4.97) | 9.15 (4.92) | 10.39 (5.32) | 10.54 (5.53) | 10.38 (5.46) |

| NIAAA | 3.20 (2.54) | 3.03 (2.24) | 3.40 (2.31) | 3.34 (2.35) | 2.98 (2.43) |

| Mania Hx | 22 (14.57) | 15 (11.90) | 20 (14.71) | 25 (16.03) | 25 (15.15) |

| Psychosis Hx | 2 (1.32) | 1 (0.79) | 3 (2.21) | 3 (1.92) | 3 (1.82) |

| Using other health apps | 128 (87.67) | 105 (84) | 116 (86.57) | 124 (79.49) | 125 (77.64) |

| Per cent of rural | 5 (2.37) | 3 (1.44) | 7 (3.40) | 9 (3.78) | 5 (2.14) |

| In treatment | 84 (57.5) | 64 (52.5) | 74 (56.5) | 84 (55.3) | 81 (50.9) |

Mean (SD) for continuous variables; number (percentage) for categorical.

HT, health tips; Hx, medical history; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PST, problem solving therapy.

Clinical characteristics

The sample was moderately depressed at baseline, with a PHQ-9 mean score of 13.9 (SD=5.1). There was a significant association between age and depression severity, Spearman's r=−0.11, p<0.001. There was no significant difference in depression severity among gender (t(365.85)=0.63, p=0.53) or ethnic groups, (F(6, 1091)=1.37, p=0.22). Fifty-one per cent reported comorbid anxiety, 53% reported comorbid alcohol misuse, 16% reported a history of psychosis or mania. In total, 54.5% of our sample was receiving mental health treatment for their depression. This sample mirrored the ethnic disparities in mental health service use found in the general population, with 63% of non-Hispanic white participants in treatment, and only 42% of ethnic minorities were in treatment ( =28.6, p<0.001, OR=2.29). There were no significant differences in depression severity among individuals randomised to the three primary arms (F[2, 623]=0.14, p=0.87; see table 1).

=28.6, p<0.001, OR=2.29). There were no significant differences in depression severity among individuals randomised to the three primary arms (F[2, 623]=0.14, p=0.87; see table 1).

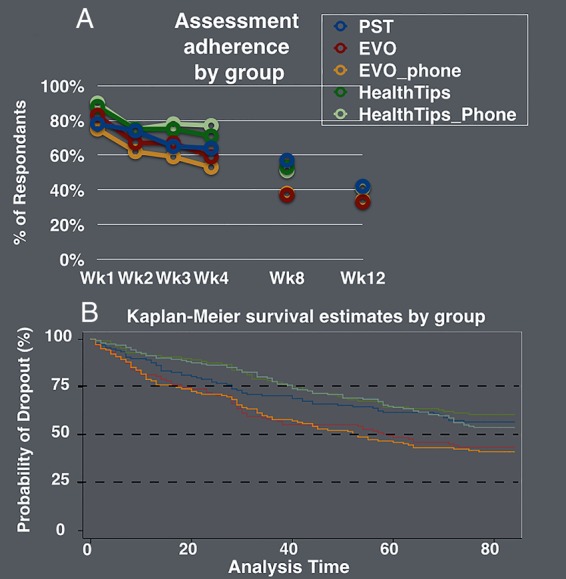

Engagement

Sixty-six per cent of the sample completed the 4-week assessment, 50% completed the 8-week assessment and 41% completed the 12-week assessment (see figure 3A). There was no adherence difference by group (F(2, 241)=2.50, p=0.08) and no time by group interaction (F(3.55, 428.14)=1.93, p=0.11). We found similar adherence to the cognitive assessment tool, with neither a group (F=0.46, p=0.63) nor interaction effect present (F=0.91, p=0.42). Although lower assessment adherence was observed in the more depressed participants, younger participants, and participants with lower education, the effects sizes were small (see table 2).

Figure 3.

Intervention and assessment adherence. (A) Percentage of individuals who responded to their mood assessment during the treatment phase (first 4 weeks) and follow-up periods (weeks 8 and 12). (B) Kaplan-Meier survival estimates per study arm illustrating survival distributions of time to drop-out (last day of recorded activity) over the course of the study (84 days).

Table 2.

Baseline demographics*

| Assessment adherence | Adherent | Non-adherent | p Value | Effect size† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9‡ | 13.25 (5.0) | 14.5 (4.9) | 0.001 | 0.24 |

| Age‡ | 34.7 (11.4) | 30.7 (10.8) | <0.001 | 0.36 |

| Education§ | <0.01 | 0.25 | ||

| <12 years | 61 (17.09) | 95 (25.54) | ||

| College | 206 (57.70) | 211 (56.72) | ||

| Graduate | 90 (25.21) | 66 (17.74) | ||

| Gender¶ | 80 (22.4) | 75 (20.2) | 0.46 | 0.11 |

| Minority** | 130 (36.4) | 161 (43.3) | 0.06 | 0.23 |

| Income†† | 0.06 | 0.33 | ||

| $20 000 or less | 81 (39.32) | 91 (47.40) | ||

| $20 000–$40 000 | 50 (24.27) | 52 (27.08) | ||

| $40 000–$60 000 | 34 (16.50) | 30 (15.62) | ||

| $60 000–$80 000 | 21 (10.19) | 7 (3.65) | ||

| $80 000–$100 000 | 6 (2.91) | 6 (3.12) | ||

| $100 000+ | 14 (6.80) | 6 (3.12) |

*Means and SDs unless otherwise specified.

†All effect sizes converted to Cohen's d.

‡Welch t test.

§Pearson χ2 test; number and percentage.

¶Pearson χ2 test; number and percentage of males.

**Pearson χ2 test; number and percentage of ethnic minorities.

††Fisher's exact test; number and percentage.

PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was conducted to determine whether intervention assignment or any baseline demographic variables predicted drop-out status. The log-rank test revealed a significant difference between the survival distributions between groups ( =19.27, p<0.001), with the EVO arm having significantly earlier time to drop-out than the PST arm (

=19.27, p<0.001), with the EVO arm having significantly earlier time to drop-out than the PST arm ( =7.45, p=0.01) or HT (

=7.45, p=0.01) or HT ( =17.51, p<0.001) arms (see figure 3B). We did not find a significant difference in survival distributions for those with high versus low PHQ-9 scores (using a PHQ-9 score of 10 as a cut-point,

=17.51, p<0.001) arms (see figure 3B). We did not find a significant difference in survival distributions for those with high versus low PHQ-9 scores (using a PHQ-9 score of 10 as a cut-point,  =2.29, p=0.13). There was no significant difference in survival distributions between non-Hispanic whites and ethnic minorities (

=2.29, p=0.13). There was no significant difference in survival distributions between non-Hispanic whites and ethnic minorities ( =2.13, p=0.14). Participants who received bonus pay remained in the study longer than those who did not receive a bonus (

=2.13, p=0.14). Participants who received bonus pay remained in the study longer than those who did not receive a bonus ( =11.82, p<0.001). Bonus pay was for assessment completion, not intervention app use.

=11.82, p<0.001). Bonus pay was for assessment completion, not intervention app use.

Cost

Total study costs included participant payments ($23 320), website/enrolment portal/database development ($46 507), and salaried staff time (3; 2 student volunteers also assisted) over the 9 months the study was active ($58 917), summing to a total of $128 444. The total amount spent on for this project, including staff costs, development and β testing of the UCSF developed apps (ACE and iPST), and licensing fees for the use of the other apps (EVO and Ginger.io) was $314 264 over 2 years.

Discussion

The results from this study have a number of important implications for the future of RCTs in mental health. First, we recruited a large sample of depressed participants in a short period of time and with minimal cost and effort. Currently, the typical RCT takes 4–5 years to complete, and another 1–2 years before the outcomes from these trials are reported publically. Rapid recruitment has the potential for quickly testing intervention efficacy and effectiveness, and ultimately moving effective treatments into practice while identifying and preventing the proliferation of ineffective, even unsafe, treatments. Second, we were able to recruit a highly representative sample of the US population, without any specific cultural adaptations or targeted advertising. Remote research methods could address decades-long concerns about the generalisability of clinical findings to minority samples not typically represented in clinical research. Finally, the cost of a fully remote RCT could allow for greater distribution of dwindling clinical research and development funds from federal, foundation and industry sponsors. Investment in large-scale clinical trials is a costly endeavour, resulting in the need to focus funds on only a few research areas. Although not all mental health RCTs should be fully remote, particularly those that test hypotheses about biological or neurological processes that can only be measured with immobile devices, the methods presented here, such as automated data collection of neuropsychological processes could result in substantial savings, which in turn could be invested in a diverse research portfolio.

This research method is not without its limitations. Primary among the challenges of fully remote research is the ability to keep participants engaged in the study protocol over time. Although there is an appeal to quickly recruiting and retaining large numbers of participants in an RCT, researchers and developers need to be cautious when interpreting outcomes from samples with a drop-out rate greater than 70%.30–33 However, it is important to point out here that the project was completely automated with very little contact between the participant and research team, and our retention rates were higher than in the typical internet-based RCT.34 Internet-based studies have shown that when there is more direct contact between the research team and participant through technologies such as video-over-internet protocols, retention rates are greater and less subject to bias,35 suggesting a hybrid approach may provide an optimal response.

Although we experimented with two incentive models to encourage retention, we determined that participant payment was not enough to keep engagement from waning across the course of the study, as bonus pay only encouraged participants to complete their assessments, and did not engender any additional motivation to utilise the training apps. Previous work has demonstrated that externalised benefits in the form of compensation can dull motivation,36 37 indicating that the creation of internalised reward structure to enhance motivation (eg, individualised presentation of study progress, personalised encouragements) is critical for improved adherence.

Conclusions

Mobile technology has an important role in broadening the reach and representativeness of RCTs, while substantially reducing the time to determine intervention effectiveness and reducing study costs. Although study retention remains challenging for technology-based research, innovative methods to increase motivation and study engagement could easily address this important limitation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank A Brandes-Aitken (UCSF), M Brander (UCSF) and A Bodepudi (UCSF) for assistance in data monitoring, M Gross (UCSF) and J Camire (Ekho.me) for their help in participant recruitment, J Steinmetz (Ekho.me) for database architecture, D Ziegler (UCSF) for helping with app deployment, D Albert (UCSF) for assistance in web design, L Slavik (UCSF) for accounting assistance, C Catledge (UCSF) for administrative oversight, A Piper, E Martucci, S Kellogg, J Bower, M Omerick and the entire Akili Interactive team as well as I Elson, L Kaye, S Goobich and the rest of the Ginger.io team for helping with data collection and partnering with us on this project. They also thank all the participants whose time and efforts made this work possible. Support for this research was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (P.A.A.; R34-MH100466, T32 MH0182607, K24 MH074717). JAA and JTJ had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Competing interests: AG is co-founder, chief science advisor and shareholder of Akili Interactive Labs, a company that develops cognitive training software. AG has a patent pending for a game-based cognitive training intervention, ‘Enhancing cognition in the presence of distraction and/or interruption’, on which the cognitive training application (PROJECT: EVO) that was used in this study was based.

Ethics approval: UCSF Committee for Human Research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. devices UFaDAM. Secondary. http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/productsandmedicalprocedures/connectedhealth/mobilemedicalapplications/default.htm.

- 2.Campbell KR. An apple a day: changing medicine through technology and engagement. Future Cardiol 2015;11:259–60. 10.2217/fca.15.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friend SH. App-enabled trial participation: tectonic shift or tepid rumble? Sci Transl Med 2015;7:297ed10 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohr D. Highlight: A Therapist in One's Pocket: mHealth to Improve Access to Mental Health Care. Secondary Highlight: A Therapist in One's Pocket: mHealth to Improve Access to Mental Health Care, 2015. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/strategic-planning-reports/highlights/highlight-a-therapist-in-ones-pocket-mhealth-to-improve-access-to-mental-health-care.shtml

- 5.Insel T. Something Interesting is Happening. Secondary Something Interesting is Happening, 2015. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/director/2015/something-interesting-is-happening.shtml

- 6.Price M, Yuen EK, Goetter EM, et al. mHealth: a mechanism to deliver more accessible, more effective mental health care. Clin Psychol Psychother 2014;21:427–36. 10.1002/cpp.1855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silow-Carroll S, Smith B. Clinical management apps: creating partnerships between providers and patients. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2013;30:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parmanto B, Pramana G, Yu DX, et al. iMHere: a novel mHealth system for supporting self-care in management of complex and chronic conditions. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2013;1:e10 10.2196/mhealth.2391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexopoulos GS, Raue PJ, McCulloch C, et al. Clinical case management versus case management with problem-solving therapy in low-income, disabled elders with major depression: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015;24:50–9. 10.1177/0894439315578240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McAlindon T, Formica M, Kabbara K, et al. Conducting clinical trials over the internet: feasibility study. BMJ 2003;327:484–7. 10.1136/bmj.327.7413.484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shere M, Zhao XY, Koren G. The role of social media in recruiting for clinical trials in pregnancy. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e92744. 10.1371/journal.pone.0092744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caldwell PH, Hamilton S, Tan A, et al. Strategies for increasing recruitment to randomised controlled trials: systematic review. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000368 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watson JM, Torgerson DJ. Increasing recruitment to randomised trials: a review of randomised controlled trials. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006;6:34 10.1186/1471-2288-6-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Titov N, Andrews G, Schwencke G, et al. Randomized controlled trial of Internet cognitive behavioural treatment for social phobia with and without motivational enhancement strategies. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2010;44:938–45. 10.3109/00048674.2010.493859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez AD, Mathers CD. Measuring the global burden of disease and epidemiological transitions: 2002–2030. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2006;100:481–99. 10.1179/136485906X97417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torres ER. Disability and comorbidity among major depressive disorder and double depression in African-American adults. J Affect Disord 2013;150:1230–3. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001547 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes-Morley A, Young B, Waheed W, et al. Factors affecting recruitment into depression trials: systematic review, meta-synthesis and conceptual framework. J Affect Disord 2015;172:274–90. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tryphonopoulos PD, Letourneau N. Challenges and opportunities in recruitment of depressed mothers: lessons learned from three exemplar studies. Ann Psychiatry Mental Health 2015;3:1022. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gross MS, Liu NH, Contreras O, et al. Using Google AdWords for international multilingual recruitment to health research websites. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e18 10.2196/jmir.2986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 2003;41:1284–92. 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rollman BL, Belnap BH, Mazumdar S, et al. Symptomatic severity of PRIME-MD diagnosed episodes of panic and generalized anxiety disorder in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:623–8. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0120.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nezu AM. Efficacy of a social problem-solving therapy approach for unipolar depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 1986;54:196–202. 10.1037/0022-006X.54.2.196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unutzer J, Katon W, Williams JW Jr, et al. Improving primary care for depression in late life: the design of a multicenter randomized trial. Med Care 2001;39:785–99. 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaca FE, Winn D, Anderson CL, et al. Six-month follow-up of computerized alcohol screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment in the emergency department. Subst Abus 2011;32:144–52. 10.1080/08897077.2011.562743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;11(Suppl 3):89–95. 10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, et al. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int J Psychiatry Med 1997;27:93–105. 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bishop B.2012. How rural are the states? Secondary how rural are the states? http://www.dailyyonder.com/how-rural-are-states/2012/04/03/3847/

- 30.Head BF, Dean E, Flanigan T, et al. Advertising for cognitive interviews: a comparison of Facebook, Craigslist, and Snowball recruiting. Soc Sci Comput Rev 2015. doi:10.1177/0894439315578240 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramo DE, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ. Reaching young adult smokers through the internet: comparison of three recruitment mechanisms. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12:768–75. 10.1093/ntr/ntq086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arab L, Hahn H, Henry J, et al. Using the web for recruitment, screen, tracking, data management, and quality control in a dietary assessment clinical validation trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2010;31:138–46. 10.1016/j.cct.2009.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warren J, Smalley KB, Barefoot KN. Recruiting rural and urban LGBT populations online: differences in participant characteristics between email and Craigslist approaches. Health Technol 2015;5:103–14. 10.1007/s12553-015-0112-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray E, Khadjesari Z, White IR, et al. Methodological challenges in online trials. J Med Internet Res 2009;11:e9 10.2196/jmir.1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bull SS, Vallejos D, Levine D, et al. Improving recruitment and retention for an online randomized controlled trial: experience from the Youthnet study. AIDS Care 2008;20:887–93. 10.1080/09540120701771697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cruz M, Pincus HA, Harman JS, et al. Barriers to care-seeking for depressed African Americans. Int J Psychiatry Med 2008;38:71–80. 10.2190/PM.38.1.g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Etten D. Psychotherapy with older adults: benefits and barriers. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2006;44:28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.