Abstract

Objectives

Poor weight gain during the first weeks of life in preterm infants is closely associated with the risk of developing the retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) and insufficient nutrition might be an important contributing factor. This study aimed to evaluate the effect of energy and macronutrient intakes during the first 4 weeks of life on the risk for severe ROP (stages 3–5).

Study design

A population-based study including all Swedish extremely preterm infants born before 27 gestational weeks during a 3-year period. Each infant was classified according to the maximum stage of ROP in either eye as assessed prospectively until full retinal vascularisation. The detailed daily data of actual intakes of enteral and parenteral nutrition and growth data were obtained from hospital records.

Results

Of the included 498 infants, 172 (34.5%) had severe ROP and 96 (19.3%) were treated. Energy and macronutrient intakes were less than recommended and the infants showed severe postnatal growth failure. Higher intakes of energy, fat and carbohydrates, but not protein, were significantly associated with a lower risk of severe ROP. Adjusting for morbidity, an increased energy intake of 10 kcal/kg/day was associated with a 24% decrease in severe ROP.

Conclusions

We showed that low energy intake during the first 4 weeks of life was an independent risk factor for severe ROP. This implies that the provision of adequate energy from parenteral and enteral sources during the first 4 weeks of life may be an effective method for reducing the risk of severe ROP in extremely preterm infants.

Keywords: growth failure, macronutrients, malnutrition, nutritional intakes, preterm infants

What is already known on this topic.

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is a common complication in preterm infants. Low birth weight and poor early weight gain are known risk factors for ROP.

What this study adds.

Low energy intake (parenteral and enteral) during the first 4 weeks of life is an independent risk factor for severe ROP in extremely preterm infants.

Introduction

The retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is a common complication in preterm infants, especially in extremely preterm infants (<27 gestational weeks) and may lead to severe visual impairment. Consequently, ROP remains one of the leading causes of childhood blindness in the US and Europe.1 The incidence of severe ROP (stages 3–5) in extremely preterm infants born in countries with well-developed neonatal intensive care ranges between 10% and 35%.2 The disparities in incidence may be partly explained by different survival rates of the most preterm infants but may also reflect varying exposures to risk factors at different hospitals.

Prematurity and oxygen exposure are the two most well-known risk factors for ROP development;3 ROP has a two-phase pathogenesis. In the first phase, during the first weeks of life, the hyperoxia of the immature retina leads to a suppression of growth factors and an arrested retinal vascularisation.2 However, ROP occurs even when oxygen administration is strictly controlled,4 and very little is known about other risk factors in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) environment contributing to this disrupted retinal vascular growth.

Extremely preterm infants are also at high risk of malnutrition while treated at the NICU and commonly show severe postnatal growth failure during the first 4 weeks of life.5 It has previously been shown that a poor weight gain during the first few weeks of life in preterm infants is closely associated with the risk of developing ROP,6–8 suggesting that insufficient nutrition might be an important contributing factor. However, there is a paucity of studies regarding the possible impact of early nutrition on ROP incidence in extremely preterm infants.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of energy and macronutrient intakes during the first 4 weeks of life on the risk of severe ROP in a population-based cohort of extremely preterm infants in Sweden and to assess the possible independent effects of these nutrient intakes when taking other risk factors into account.

Methods

Study population

In this study, we used data from the Extremely Preterm Infants in Sweden Study (EXPRESS). This is a population-based cohort, including all infants with a gestational age at birth of 22 weeks + 0 days to 26 weeks + 6 days born between 1 April 2004 and 31 March 2007. Comprehensive data on cohort characteristics, neonatal morbidity, infant mortality and early nutrition and growth have been previously reported.5 9–11

For the current study, we included all infants from the EXPRESS cohort who were evaluated for ROP until full retinal vascularisation, except those with major congenital or chromosomal anomalies. The final study cohort consisted of 498 infants.

Data collection

ROP data were collected prospectively for all infants in the EXPRESS cohort as described previously.12 Briefly, the screening for ROP was performed weekly or biweekly from the fifth postnatal week and continued until the retina was completely vascularised or regression of ROP was observed. ROP was classified according to the revised international classification from 2005.13 Each infant was classified according to the maximum stage of ROP in either eye. For treatment decisions, the Early Treatment for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group recommendations criteria were followed.14

Detailed nutrition and growth data were obtained retrospectively from hospital records as previously described.5 In summary, data on actual intakes of all enteral and parenteral fluids were retrieved for each day of life from day 0 (birth) through day 28. In total, nutrition data from 14 442 days were collected from the included infants. All available data on weight, length and head circumference were also retrieved. Nutrition was assessed as intakes of energy (kcal/kg/day) and macronutrients (protein, fat and carbohydrates, (g/kg/day)) from all parenteral and enteral products. Nutrient intakes were determined using nutritional content data from the manufacturers and from human milk analyses. The methods and results from the human milk analyses have been reported in detail previously.15 Total fluid and nutrient intakes included transfused blood products as well as drug infusions and flush solutions. Total macronutrient intakes were calculated as the sum of intakes from enteral and parenteral sources. SD scores (SDS) for weight were calculated as previously described5 based on a Swedish, gender-specific growth chart.16

Background data and NICU data were prospectively collected as previously described.5 9 10 In this study, we used data on gestational age at birth, birth weight (grams and SDS), Clinical Risk Index for Babies (CRIB) score, mechanical ventilation (days), postnatal steroid treatment (days), antibiotics treatment (days), patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) (any treatment or surgery), intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH) grade ≥3 and study hospital (categorical variable). The blood transfusions (mL/day) and proportion of enteral fluids were retrieved with the nutritional data and were also included as markers of morbidity.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed by using SPSS Statistical software (V.21.0 for Windows, SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) and R (V.3.01).17 Logistic regression analyses were first used to assess the effects of each of the different risk factors on the risk of severe ROP, adjusting for gestational age and birth weight. Significant risk factors were then further analysed in multivariate logistic regression models using forward conditional approach. p Values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data are stated as mean and 95% CI.

Logistic regression analyses were performed, adjusting for gestational age and birth weight, testing the associations between intakes of energy and each macronutrient (protein, carbohydrates and fat) and severe ROP during different time intervals during the first month of life: week 1 (days 0–7), week 2 (days 8–14), week 3 (days 15–21), week 4 (days 22–28) and weeks 1–4 (days 0–28). Energy intake and the energy percent of protein, carbohydrate and fat intakes between 0 and 28 days were then included in a forward conditional multivariate regression analysis, with severe ROP as the dependent variable, adjusting for gestational age and birth weight.

Relevant morbidity-associated variables were tested using logistic regression analyses, adjusting for gestational age and birth weight. A previous article identified poor growth, PDA, mechanical ventilation and postnatal steroids as risk factors of severe ROP.10

Since CRIB score, IVH ≥ grade 3, postnatal steroids and antibiotics interferes with postnatal growth,5 9 these variables were included together with data on the blood transfusions and proportion of enteral fluid intake as markers of morbidity.

In a final model, all significant risk factors from the above analyses were included in a multivariate logistic regression model using a forward conditional approach: gestational age, birth weight, energy intake 0–28 days, mechanical ventilation 0–28 days, blood transfusions 0–28 days, proportion of enteral fluid intake 0–28 days and PDA surgery at any time before ROP treatment. To consider other, not included, risk factors that may vary between hospitals, a second multivariate analysis was performed, including a categorical hospital variable.

Results

Of the initial cohort of 707 live born infants, 196 were excluded due to death before complete ROP evaluation and an additional seven were excluded due to major congenital or chromosomal anomalies (two limb reduction defects, one gastrointestinal malformation, three multiple congenital anomalies and one Down's syndrome). Of the remaining 504, complete nutritional data was available for 498 infants (99%). Mean gestational age was 25.4±1.1 weeks and mean birth weight was 776±167 g (SDS −0.75±1.21), 55% were male. The distribution of stages of ROP was as follows: 27.5% had no ROP; 15.3% had ROP stage 1; 22.7% had ROP stage 2; 33.3% had ROP stage 3; 0.6% had ROP stage 4 and 0.6% had ROP stage 5.

Of the 498 infants, 172 (34.5%) had severe ROP (stages 3–5) and 96 (19.3%) were treated. The intakes of fluids, energy and macronutrients during the first 4 weeks of life in infants with no ROP, ROP stages 1–2 and ROP stages 3–5 are shown in table 1. The infants also showed a severe postnatal growth failure, with a mean±SD decrease in SDS for the weight of 1.4±0.6 during the first week of life and an additional decrease of 0.7±0.8 in SDS during the following 3 weeks.

Table 1.

Intakes of fluids, energy and macronutrients during the first 4 weeks of life in extremely preterm infants born below 27 weeks of gestation

| No ROP n=137 |

ROP stages 1–2 n=189 |

ROP stages 3–5 n=172 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intakes (kg/day) | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Fluids* (mL) | 154 | 13.5 | 149 | 13.2 | 149 | 15.9 |

| Energy (kcal) | 108 | 13.3 | 102 | 13.1 | 97 | 13.5 |

| Protein (g) | 3.0 | 0.4 | 3.0 | 0.4 | 3.0 | 0.4 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 11.5 | 1.0 | 11.2 | 1.0 | 11.0 | 1.2 |

| Fat (g) | 5.2 | 1.2 | 4.8 | 1.2 | 4.4 | 1.2 |

Data are shown as mean values ±SD.

*Includes all fluids such as enteral and parenteral nutrition, blood products and flush solutions.

ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

The associations between intakes of energy and each macronutrient (protein, carbohydrates and fat) and severe ROP during different time intervals are shown in table 2. Similar analyses were also performed for the time intervals 0–14, 15–28, 8–21, 0–21 and 8–28 days (data not shown). A higher energy and fat intake at each of these time intervals were significantly associated with a lower risk of severe ROP, with the lowest ORs at 0–21 and 0–28 days. A higher intake of carbohydrates at most time intervals were significantly associated with a lower risk of severe ROP, with the lowest OR at 0–28 days. A higher intake of protein was significantly associated with a lower risk of severe ROP during days 22–28 but not during any of the other time intervals (table 2). In these analyses, energy intake had the lowest OR and the highest level of significance. In the multivariate analysis including energy and macronutrient intakes at 0–28 days, only energy intake remained a significant predictor of severe ROP.

Table 2.

Intakes of energy and macronutrients and associations with retinopathy of prematurity (stages 3–5) during the first 4 weeks of life (n=498)

| Energy | Protein | Carbohydrates | Fat | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kcal (SD) | OR† | 95% CI | Gram (SD) | OR‡ | 95% CI | Gram (SD) | OR‡ | 95% CI | Gram (SD) | OR‡ | 95% CI | |

| Week 1 | 66 (10) | 0.75** | 0.61 to 0.92 | 2.2 (0.6) | 1.08 | 0.78 to 1.50 | 9.1 (1.3) | 0.87 | 0.75 to 1.01 | 2.2 (0.8) | 0.75* | 0.58 to 0.97 |

| Week 2 | 102 (17) | 0.80** | 0.71 to 0.92 | 3.0 (0.5) | 0.90 | 0.62 to 1.30 | 11.3 (1.4) | 0.86* | 0.74 to 0.98 | 4.7 (1.5) | 0.83** | 0.72 to 0.96 |

| Week 3 | 116 (21) | 0.82*** | 0.74 to 0.91 | 3.3 (0.6) | 0.88 | 0.63 to 1.23 | 12.0 (1.6) | 0.89 | 0.78 to 1.01 | 5.8 (1.8) | 0.82** | 0.73 to 0.92 |

| Week 4 | 124 (21) | 0.86** | 0.78 to 0.95 | 3.4 (0.7) | 0.71* | 0.52 to 0.97 | 12.4 (1.7) | 0.86* | 0.76 to 0.98 | 6.4 (1.9) | 0.88* | 0.79 to 0.98 |

| Weeks 1–4 | 102 (14) | 0.72*** | 0.62 to 0.84 | 3.0 (0.4) | 0.75 | 0.47 to 1.21 | 11.2 (1.1) | 0.76** | 0.63 to 0.92 | 4.8 (1.2) | 0.75** | 0.63 to 0.89 |

Logistic regression analysis.

Adjusted for gestational age and birth weight.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

†Energy: 10 kcal/kg/day increment.

‡Protein, carbohydrates and fat: 1 g/kg/day increment.

The associations between changes in weight SDS and the risk of severe ROP were tested within the same intervals as for macronutrient intakes, adjusting for gestational age and birth weight. There was a trend of lower risk of severe ROP with more positive weight SDS change, but this did not reach significance (table 3). However, when infants with gestational age <23 weeks at birth were excluded (n=4), this association became significant. The effects of morbidity-associated variables on the risk of severe ROP are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Postnatal predictors of retinopathy of prematurity (stages 3–5) in Swedish extremely preterm infants (n=489)

| Period | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight ΔSDS | 0–28 days | 0.79 | 0.59 to 1.07 |

| Weight ΔSDS | 8–28 days | 0.78 | 0.59 to 1.03 |

| Weight ΔSDS (GA >23 weeks) | 8–28 days | 0.75* | 0.57 to 0.99 |

| CRIB score (one step increment) | Any | 1.00 | 0.93 to 1.09 |

| Mechanical ventilation† (days) | 0–28 days | 1.19** | 1.08 to 1.33 |

| Postnatal steroids (days) | 0–28 days | 1.19 | 1.00 to 1.41 |

| Antibiotic treatment (days) | 0–28 days | 1.16 | 1.00 to 1.35 |

| Blood transfusion‡ (mL/day) | 0–28 days | 1.23** | 1.09 to 1.39 |

| PDA treatment (any) | Any | 1.95** | 1.26 to 3.02 |

| PDA surgery | Any | 2.28*** | 1.46 to 3.55 |

| IVH any§ (grade 1–4) | Any | 1.57** | 1.04 to 2.36 |

| IVH§ grade 3–4 | Any | 2.13** | 1.12 to 4.03 |

| Enteral fluids¶ (mL/kg/day) | 0–28 days | 0.85*** | 0.78 to 0.93 |

| Hospital | 0.98 | 0.95 to 1.01 |

Logistic regression analysis.

Adjusted for gestational age and birth weight.

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

†One day per week increment.

‡10 mL/kg per week increment.

§One grade increment.

¶Enteral fluids (proportion of total fluids): 10% increment.

ΔSDS, delta SD score; CRIB, clinical risk index for babies; GA, gestational age; IVH, intraventricular haemorrhage; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus.

Finally, all significant nutritional and non-nutritional risk factors from the above analyses were included in two multivariate logistic regression models, the latter also including hospital as a variable. The results are presented in table 4. Energy intake was highly significant in both of these models, p values 0.006 and 0.001, respectively.

Table 4.

Postnatal risk factors associated with retinopathy of prematurity (stages 3–5), n=498

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for hospital† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Energy intake‡ 0–28 days | 0.76** | 0.65 to 0.90 | 0.76** | 0.62 to 0.92 |

| Blood transfusions§ 0–28 days | 1.17* | 1.02 to 1.33 | 1.35** | 1.09 to 1.67 |

| Birth weight¶ (g) | 0.75*** | 0.65 to 0.87 | 0.79* | 0.66 to 0.95 |

| Gestational age†† (weeks) | n.s | 0.76* | 0.59 to 0.98 | |

| Mechanical ventilation‡‡ | 1.03* | 1.00 to 1.06 | n.s | |

| R-square for model | 0.22 | 0.26 | ||

Multivariate logistic regression.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

†Adjusted for hospital (n=7, p=0.025).

‡Energy intake: 10 kcal/kg/day increment.

§Blood transfusions: 10 mL/kg per week increment.

¶Birth weight: 100 g increment.

††Gestational age: 1 week increment.

‡‡Mechanical ventilation: 1 day increment.

n.s, non-significant.

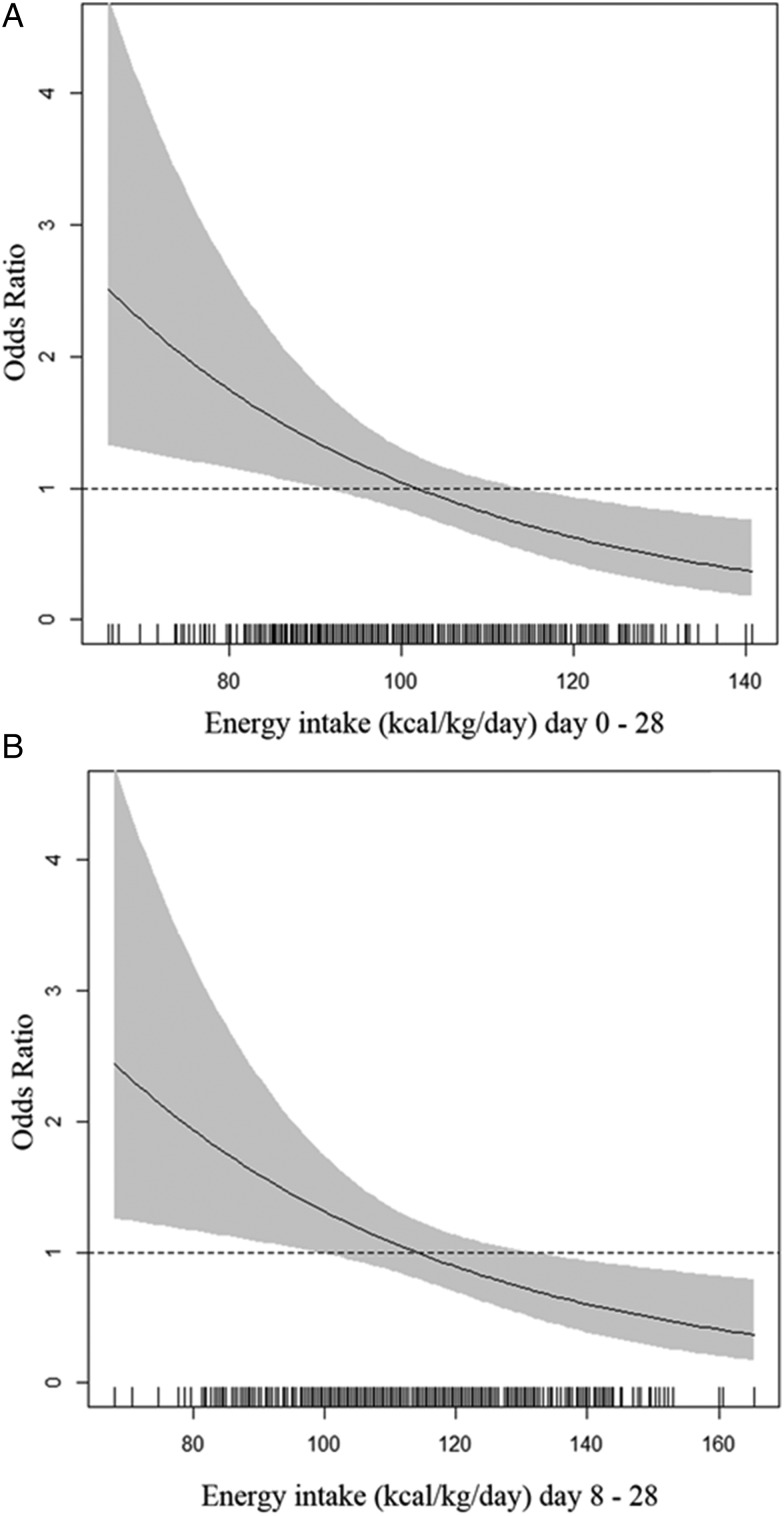

OR (95% CI) for the risk of severe ROP at different energy intakes, adjusted for birth weight, mechanical ventilation and blood transfusions, are shown in figure 1. We present OR for the interval 0–28 days (figure 1A) and also for 8–28 (figure 1B) days since the energy intakes during this period was much higher than during the first week.

Figure 1.

Odds ratio for the risk of severe retinopathy of prematurity at different energy intakes at 0–28 days (A) and at 8–28 days (B) in Swedish extremely premature infants. Adjusted for birth weight, mechanical ventilation and blood transfusions.

Discussion

The first phase of ROP development occurs during the first few weeks of life. In this population-based cohort, we found that lower energy and fat intakes (enteral plus parenteral) during the first 4 weeks of life were strongly associated with the increased risk of developing severe ROP. Low carbohydrate intakes during the same period were also significantly associated with severe ROP. Surprisingly, protein intakes were only significantly associated with severe ROP during the fourth week. In multivariate analyses, energy intake remained a highly significant explanatory variable, even when including other risk factors. In the final model, the OR for energy intake was 0.76 suggesting that an increase of energy intake by 10 kcal/kg/day during the first 4 weeks of life is associated with a decrease of 24% in the risk of developing severe ROP.

As previously reported, these infants received macronutrient intakes which were less than recommended.5 According to recent international recommendations, enteral energy requirements of very low birth weight infants beyond the first few days of life are 110–130 kcal/kg/day.18 Recommendations for parenteral energy intakes are lower: 105–115 kcal/kg/day19 or 110–120 kcal/kg/day.20 As shown in figure 1, there is not a sharp cut-off below which the risk of severe ROP increases, but the figure indicates that the lowest currently recommended intakes, that is, 105–110 kcal/kg/day may be too low, at least during days 8–28. Our data do not permit a full analysis of the reasons for infants at risk of severe ROP not receiving adequate energy intakes. However, the insufficient fortification of breast milk, lack of concentrated parenteral solutions and poor routines for nutrient intake calculations might have contributed.

The quality of lipid intake may be important since there is some evidence that increasing ω-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids reduces the risk of ROP.21 22 In the current study, only a purely soy-based lipid emulsion (Intralipid, Fresenius Kabi AB, Uppsala, Sweden) was used for parenteral nutrition, which has a very low content of ω-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. However, fatty acid intakes of the infants in this study are not known and are likely to be more variable considering that they received most of their fat intake from human milk and fatty acid contents of human milks were not analysed in this study. Our results suggest that the energy intake from fat may impact the risk of severe ROP regardless of the fatty acid content.

Low birth weight and low gestational age are well-known risk factors for ROP. Birth weight was the slightly stronger predictor and remained when adjusting for gestational age (table 4), which has also been observed in previous studies23 suggesting that intrauterine growth restriction is associated with the increased risk of ROP. Even though several previous studies have shown a significant association between a poor weight gain during the first weeks of life and severe ROP in preterm infants7 24 25 we observed a non-significant trend in the whole population and a significant association only when infants born <23 weeks of gestational age were excluded, which has already been reported.26 Since most previous studies showing this association have included more mature infants, usually with an average gestational age at birth of 27–28 weeks, our observations suggest that the association between weight gain and severe ROP in preterm infants may be weaker at the very lowest gestational ages at least during the first 4 weeks of life. Furthermore, since a low energy intake was a stronger risk factor than poor weight gain in this study, our results indicate that growth may not be in the causal chain of ROP pathogenesis, which was suggested also by VanderVeen et al.27 As we have previously shown, growth is affected by energy and protein intake and by disease-related factors.5 Growth in extremely preterm infants is also influenced by insulin growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which is lower in extremely preterm infants.28

The other independent risk factors for severe ROP that we observed in this study were mechanical ventilation and blood transfusions. Mechanical ventilation is likely a proxy for oxygen exposure, which is a known risk factor for ROP. Blood transfusions have previously been shown to be a risk factor for ROP, which might be due to increased oxidative stress due to iron load from blood transfusions.29 An alternative explanation is that blood transfusions is a proxy for high oxygen exposure in preterm infants with severe lung disease. As has been reported previously there were some regional differences in the incidence of ROP between hospitals,11 and in our analyses, this difference remained when adjusting for nutrition and morbidity. This might be due to unaccounted confounding by variables not included in our data set or possibly due to diagnostic differences. However, the fact that the hospital variable did not affect the association between energy intake and severe ROP indicates that our main result is robust.

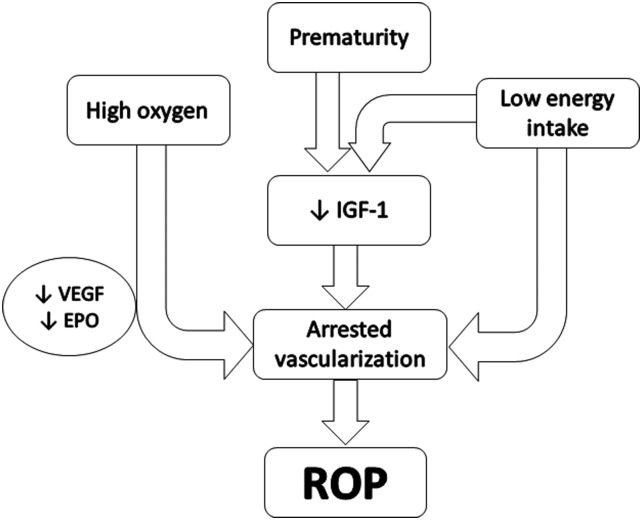

Based on our current results and previous published studies, we propose a mechanism for the first phase of ROP pathogenesis (figure 2). In this model, we suggest that a low energy intake during the first 4 weeks of life can lead to arrested vascularisation either through a decrease in IGF-1 alone or in combination with a decrease in other angiogenic promoting factors or poor nutrient supply to the growing vessels. Undernutrition with regard to energy and/or protein is known to result in reduced plasma levels of IGF-1 but there seems to be a threshold energy requirement under which the protein intake does not increase IGF-1.30 The fact that we did not find a correlation between protein intake and severe ROP (except for days 22–28) suggest that the energy intake might have been below that threshold for a majority of the infants.

Figure 2.

Proposed mechanism of the first phase of retinopathy of prematurity pathogenesis during the first four postnatal weeks. IGF-1, Insulin-like growth factor 1; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; EPO, erythropoietin.

Strengths of this study include a population-based cohort, detailed data on nutritional intakes, growth and other risk factors for ROP. Comparing with the only other similar study published27 our nutrient data for each infant is based on data from 28 consecutive days as compared with only 4 days and our study includes many more risk factors for ROP. Limitations of our study are the retrospective data collection, the lack of direct data on oxygen exposure and possible unaccounted confounding. Furthermore, the fatty acid composition of the breast milks was not analysed.

In conclusion, the results from this study suggest that the provision of adequate energy from parenteral and enteral sources during the first 4 weeks of life may be an effective method for reducing the risk of severe ROP in extremely preterm infants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fredrik Ahlsson, Eva Engström, Vineta Fellman, Mikael Norman and Elisabeth Olhager for the assistance of nutritional and growth data collection. Fredrik Serenius and Karin Källén for their contribution of basic EXPRESS cohort data, and Andreas Tornevi for statistical support.

Footnotes

Contributors: The author’s responsibilities were as follows: MD designed the study and drafted the initial manuscript. ESS was responsible for nutritional and growth data acquisition. GH, PL and AH were responsible for ROP data acquisition. ESS, PL, IÖ, GH, AH and MD analysed and interpreted data; participated in writing the manuscript; reviewed and revised the scientific content of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by Lilla Barnets Fond, Queen Silvia's Jubilee Foundation, Oskar Foundation and Swedish Nutrition Foundation (SNF) and through regional agreement between Umeå University and Västerbotten County Council on cooperation in the field of Medicine, Odontology and Health (ALF).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This study has been approved (Dnr 138-2008) by the Ethics Committee, Lund, Sweden.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kong L, Fry M, Al-Samarraie M, et al. An update on progress and the changing epidemiology of causes of childhood blindness worldwide. J AAPOS 2012;16:501–7. 10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hellstrom A, Smith LE, Dammann O. Retinopathy of prematurity. Lancet 2013;382:1445–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60178-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Askie LM, Henderson-Smart DJ, Ko H. Restricted versus liberal oxygen exposure for preventing morbidity and mortality in preterm or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(1):CD001077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartnett ME, Lane RH. Effects of oxygen on the development and severity of retinopathy of prematurity. J AAPOS 2013;17:229–34. 10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.12.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoltz Sjostrom E, Ohlund I, Ahlsson F, et al. Nutrient intakes independently affect growth in extremely preterm infants: results from a population-based study. Acta Paediatr 2013;102:1067–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lofqvist C, Andersson E, Sigurdsson J, et al. Longitudinal postnatal weight and insulin-like growth factor I measurements in the prediction of retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol 2006;124:1711–18. 10.1001/archopht.124.12.1711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Binenbaum G, Ying GS, Quinn GE, et al. The CHOP postnatal weight gain, birth weight, and gestational age retinopathy of prematurity risk model. Arch Ophthalmol 2012;130:1560–5. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.2524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hellstrom A, Ley D, Hansen-Pupp I, et al. New insights into the development of retinopathy of prematurity-importance of early weight gain. Acta Paediatr 2010;99:502–8. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01568.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The EXPRESS Group. One-year survival of extremely preterm infants after active perinatal care in Sweden. JAMA 2009;301:2225–33. 10.1001/jama.2009.771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The EXPRESS Group. Incidence of and risk factors for neonatal morbidity after active perinatal care: extremely preterm infants study in Sweden (EXPRESS). Acta Paediatr 2010;99:978–92. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01846.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serenius F, Sjors G, Blennow M, et al. EXPRESS study shows significant regional differences in 1-year outcome of extremely preterm infants in Sweden. Acta Paediatr 2014;103:27–37. 10.1111/apa.12421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Austeng D, Kallen KB, Ewald UW, et al. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity in infants born before 27 weeks’ gestation in Sweden. Arch Ophthalmol 2009;127:1315–19. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Committee for the Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity. The International Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity revisited. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:991–9. 10.1001/archopht.123.7.991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Early Treatment For Retinopathy Of Prematurity Cooperative Group. Revised indications for the treatment of retinopathy of prematurity: results of the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity randomized trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2003;121:1684–94. 10.1001/archopht.121.12.1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoltz Sjostrom E, Ohlund I, Tornevi A, et al. Intake and macronutrient content of human milk given to extremely preterm infants. J Hum Lact 2014;30:442–9. 10.1177/0890334414546354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niklasson A, Albertsson-Wikland K. Continuous growth reference from 24th week of gestation to 24 months by gender. BMC Pediatr 2008;8:8 10.1186/1471-2431-8-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Team R. R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koletzko B, Poindexter B, Uuay R. Nutritional care of preterm infants. Scientific basis and practical guidelines. Switzerland: Karger AG, 2014:297–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rigo J. Protein, Amino Acid and Other Nitrogen Compounds. In: Tsang R, Uauy R, Koletzsko B, Zlotkin S. Nutrition of the preterm infant, scientific basis and practical guidelines. 2nd edn Cincinnati, Ohio: Digital Educational Publishing, Inc., 2005:45–80. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koletzko B, Goulet O, Hunt J, et al. 1. Guidelines on Paediatric Parenteral Nutrition of the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN), Supported by the European Society of Paediatric Research (ESPR). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2005;41(Suppl 2):S1–87. 10.1097/01.mpg.0000181841.07090.f4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Connor KM, SanGiovanni JP, Lofqvist C, et al. Increased dietary intake of omega-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids reduces pathological retinal angiogenesis. Nat Med 2007;13:868–73. 10.1038/nm1591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pawlik D, Lauterbach R, Walczak M, et al. Fish-oil fat emulsion supplementation reduces the risk of retinopathy in very low birth weight infants: a prospective, randomized study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2013;38:711–16. 10.1177/0148607113499373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allegaert K, Vanhole C, Casteels I, et al. Perinatal growth characteristics and associated risk of developing threshold retinopathy of prematurity. J AAPOS 2003;7:34–7. 10.1016/S1091-8531(02)42015-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu C, Lofqvist C, Smith LE, et al. for the WINROP Consortium. Importance of early postnatal weight gain for normal retinal angiogenesis in very preterm infants: a multicenter study analyzing weight velocity deviations for the prediction of retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol 2012;130:992–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallace DK, Kylstra JA, Phillips SJ, et al. Poor postnatal weight gain: a risk factor for severe retinopathy of prematurity. J AAPOS 2000;4:343–7. 10.1067/mpa.2000.110342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lundgren P, Stoltz Sjostrom E, Domellof M, et al. WINROP identifies severe retinopathy of prematurity at an early stage in a nation-based cohort of extremely preterm infants. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e73256 10.1371/journal.pone.0073256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.VanderVeen DK, Martin CR, Mehendale R, et al. Early nutrition and weight gain in preterm newborns and the risk of retinopathy of prematurity. PLoS ONE 2013;8: e64325 10.1371/journal.pone.0064325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hellstrom A, Engstrom E, Hard AL, et al. Postnatal serum insulin-like growth factor I deficiency is associated with retinopathy of prematurity and other complications of premature birth. Pediatrics 2003;112:1016–20. 10.1542/peds.112.5.1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dani C, Reali MF, Bertini G, et al. The role of blood transfusions and iron intake on retinopathy of prematurity. Early Hum Dev 2001;62:57–63. 10.1016/S0378-3782(01)00115-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maggio M, De Vita F, Lauretani F, et al. IGF-1, the cross road of the nutritional, inflammatory and hormonal pathways to frailty. Nutrients 2013;5:4184–205. 10.3390/nu5104184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]