Abstract

To study bacterial coinfection following 1918 H1N1 influenza virus infection, mice were inoculated with the 1918 influenza virus followed by Streptococcus pneumoniae 72 h later. Coinfected mice exhibited markedly more severe disease, shortened survival time and more severe lung pathology, including widespread thrombi. Transcriptional profiling revealed activation of coagulation only in coinfected mice, consistent with the extensive thrombogenesis observed. Immunohistochemistry showed extensive expression of tissue factor (F3) and prominent deposition of neutrophil elastase on endothelial and epithelial cells in coinfected mice. Lung sections of SP-positive 1918 autopsy cases showed extensive thrombi and prominent staining for F3 in alveolar macrophages, monocytes, neutrophils, endothelial and epithelial cells, in contrast to coinfection-positive 2009 pandemic H1N1 autopsy cases. This study reveals that a distinctive feature of 1918 influenza virus and SP coinfection in mice and humans is extensive expression of tissue factor and activation of the extrinsic coagulation pathway leading to widespread pulmonary thrombosis.

Keywords: 1918 influenza, Streptococcus pneumoniae, coinfection, inflammation, extrinsic pathway of coagulation, pulmonary thrombosis

Introduction

The 1918 influenza pandemic was responsible for the deaths of ∼50 million people [1]. There is abundant evidence for secondary bacterial pneumonia being the predominant cause of death. A review of detailed epidemiology, pathology and microbiology findings in >8 000 post-mortem examinations consistently implicated secondary bacterial pneumonia, caused by common upper respiratory-tract bacteria, in most fatal influenza cases [2,3].

Enhanced pathology associated with viral-bacterial coinfection is well documented and several possible mechanisms have been proposed (reviewed in [4,5]). Specifically, viral-mediated changes in the respiratory tract, including epithelial damage, alterations in airway function and exposure of receptors, are thought to prime the upper airway for secondary bacterial infection [4]. Both enhanced and dysfunctional innate immune responses have also been implicated in the increased severity of coinfection [5]. Finally, bacteria-mediated cleavage of the viral haemagglutinin (HA) antigen has been suggested as a mechanism for increased viral replication following bacterial challenge, potentially leading to more severe lung damage and poor outcome in coinfected mice [6,7]. Interestingly, synergism during coinfection appears to be influenced by both viral and bacterial strain-specific factors [8]. Differences in the abilities of Streptococcus pneumoniae (SP) strains to replicate in lungs of mice following infection with influenza was associated with differential mortality, suggesting strain specificity in the ability of SP to cause pneumonia during influenza infection [9]. Secondary infection with SP resulted in a lethal coinfection in mice inoculated with 2009 pandemic H1N1, but not seasonal H1N1, and was associated with loss of airway basal epithelial cells and lung repair responses [10]. Similar studies suggest bacterial strain-related differences also influence the synergy between Staphylococcus aureus and influenza virus [11].

Infection with 1918 influenza has been shown to result in severe lung pathology typified by necrotizing bronchitis, bronchiolitis, neutrophil-predominant alveolitis, and acute oedema associated with significant activation of antiviral, pro-inflammatory and cell death response genes in lung tissue in animals and humans [12-15]. The inflammatory response induced by 1918 infection has been shown to be immunopathogenic in mice and results in significant activation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) with marked oxidative damage to respiratory epithelial cells [16].

While secondary bacterial infections caused the majority of deaths during the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic, little is known about the underlying mechanisms responsible for the synergy between 1918 influenza and bacteria. In the current study, effects of secondary SP infection in mice that were infected with the 1918 influenza virus were investigated. SP was chosen because it was the most commonly identified bacteria in fatal 1918 influenza cases [2,3]. The results show that SP secondary infection greatly enhanced lung pathology in mice; it shortened survival, increased early bacterial replication, and altered the host response to infection, with evidence including increased neutrophil activation and activation and aggregation of platelets and clotting. (AQ: please check this sentence retains your intended meaning). Histological and immunohistochemical analyses validated this thrombogenic response and showed abundant thrombi and extensive staining for F3. Importantly, staining of two SP-positive 1918 autopsy cases showed similar extensive F3 staining along with abundant thrombi. In contrast, minimal F3 staining and no thrombi was observed in SP- or Streptococcus pyogenes-positive 2009 pandemic H1N1 fatalities. These data support and expand observations of pulmonary thrombi observed in post mortem examinations of 1918 virus autopsies [17,18] and demonstrate that widespread pulmonary vascular thrombogenesis was a feature of 1918 pandemic H1N1 and SP coinfection, which may help explain the high death toll of the 1918 pandemic.

Materials and Methods

Viruses and bacteria

The reconstructed 1918 influenza virus, A/Brevig Mission/1/1918 (H1N1), was rescued and titred using published protocols [16,19]. SP strain A66.1 (serotype 3; x0en10; Perkin Elmer) and grown as described in [10]. All work with the reconstructed 1918 influenza virus was performed in enhanced BSL-3 and enhanced ABSL-3 laboratories at the NIH in accordance with the Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL), 5th Edition, and the Division of Select Agents and Toxins at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (DSAT/CDC) and the NIH and under supervision of the Biosurety Program of the NIH Department of Health and Safety.

Mouse infection studies

Groups of five 8-9 week old female BALB/c mice (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME) were placed under light anaesthesia as described in [10] and inoculated with 5×102 PFU of the reconstructed 1918 H1N1 influenza virus; sham inoculated with PBS at this time (day 0); or inoculated intra nasally (AQ: please check this substitution) with 105 colony-forming units (CFU) of SP at 3 days post-virus. Virus-alone groups were sham inoculated with PBS at day 3. Body weights were measured daily for 7-10 d post-infection and mice were humanely euthanized if they lost more than 25% of starting body weight. Lungs from three animals were collected for RNA isolation and from two animals for pathology at day 3 to 6 post-1918 (day 0 to +3 post-SP, respectively). Lungs collected for pathology were inflated with 10% neutral buffered formalin at the time of isolation. All experimental animal work was performed in accordance with United States Public Health Service (PHS) Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Mice in an enhanced ABSL-3 laboratory at NIH following approval of animal safety protocols by the NIAID Animal Care and Use Committee and in accordance with DSAT/CDC.

RNA isolation and expression microarray analysis

Total RNA was isolated from lungs and used for gene expression profiling using Agilent Mouse Whole Genome 44K microarrays as described in [10,16] and Supporting Information online. In brief, RNA from three biological replicates per condition was labelled and hybridized to individual arrays and processed as described in [10,16]. Data normalization was performed in Analyst using central tendency followed by relative normalization using pooled RNA from mock infected mouse lung (n=4) as a reference. Transcripts showing differential expression (2-fold, p< 0.01) between infected and control mice were identified by standard t test. The Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was used to correct for false positive rate in multiple comparisons. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis was used for gene ontology and pathway analysis. The complete microarray dataset has been deposited in NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus [20] and is accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE70445.

Reverse Transcription Quantitative-PCR

RT-qPCR was used to estimate bacterial and viral loads in lung tissue. Reverse transcription of total lung RNA was performed with primers specific for influenza M gene, mouse Gapdh, SP 16S rRNA, endA, nanA, nanB, or ply using standard protocols. Primers are listed in Table S1. Quantification of each gene's CT was graphed relative to that of the calibrator as described in [10].

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

Mouse tissue samples were processed for histopathological examination using standard protocols. Gram staining was performed using the method of Brown and Hopps, and Movat's pentachrome staining was performed using standard protocols. Mouse immunohistochemical studies were performed using standard protocols [19] following heat-mediated antigen retrieval using antibodies specific to CD11b, ELANE, F3, MPO, thrombin, Ly6g (clone 1A8) or TPA as described in Supporting Information. Immunohistochemical studies on human 1918 and 2009 pandemic H1N1 autopsy cases used 5μm thick sections cut from the FFPE lung tissue blocks from cases described previously [3,21] and stained for F3 as described in Supporting Information. These samples were considered exempt for human subjects review under US Government guidelines (http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/policy/checklists/decisioncharts.html#c5).

Results

Bacterial coinfection accelerated mortality of 1918 pandemic influenza virus infection

To study effects of secondary bacterial infection following primary influenza virus infection, mice were inoculated intra nasally with 5×102 PFU of the 1918 virus followed by inoculation with 105 CFU SP 72 h later. Mice inoculated with 1918- alone exhibited significant weight loss with 100% mortality by day 11 post-inoculation (Fig. 1A-B). Mice inoculated with SP-alone displayed weight loss with 100% mortality by day 7 post-SP (day 10 post-1918). Mice coinfected with 1918 virus followed by SP 72 h later (1918+SP), showed more severe illness than mice inoculated with virus- or SP-alone, with 100% mortality by day 6 post-1918 (day +3 post-SP). Significantly, the majority of deaths in 1918+SP groups occurred in moribund mice prior to reaching 25% weight loss euthanasia criteria. The results shown are typical of three independent experiments.

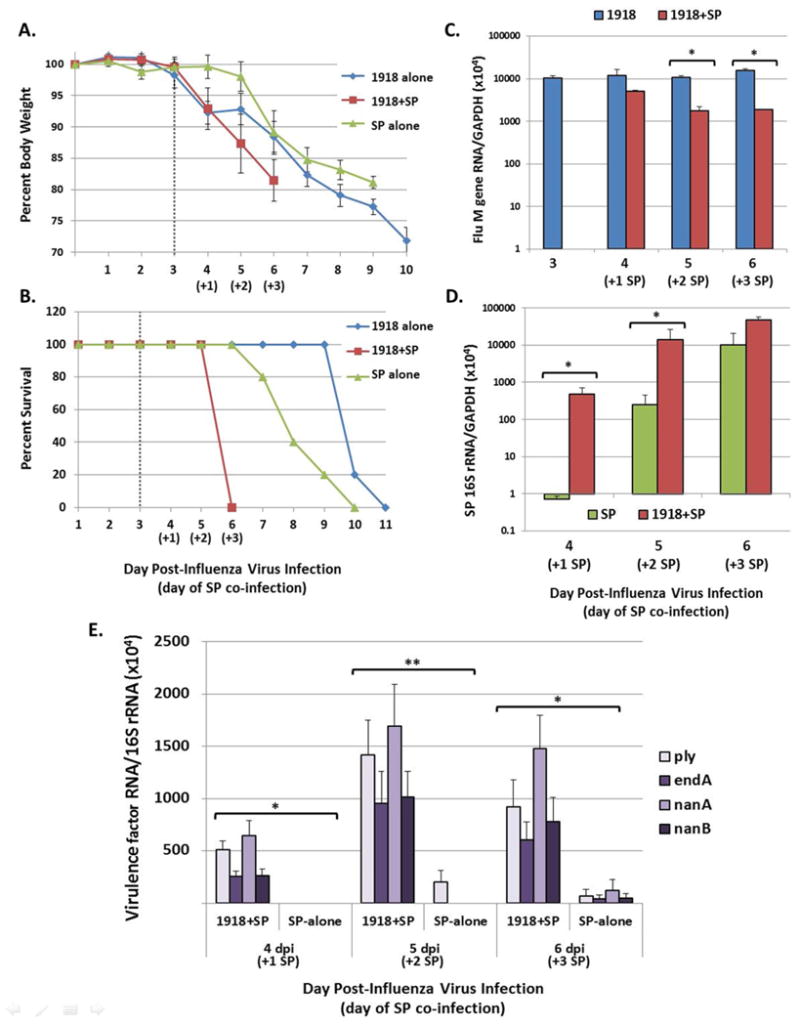

Fig. 1. Coinfection of 1918 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus and SP shortens survival and increases bacterial growth and virulence factor expression.

Groups of mice were inoculated as described in Materials and methods. (A) Change in body weight following initial infection in 1918 virus-alone, SP-alone and 1918+SP infected groups. Inoculation with SP is indicated at 3 dpi following influenza virus by the dashed line. (B) Survival of 1918 virus-alone, SP-alone and 1918+SP infected mice. These data are representative of three independent experiments. (C) Quantification of influenza virus M gene mRNA expression and (D) quantification of bacterial 16S rRNA present in lung tissue using RT-qPCR. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of 2−ΔCt values relative to Gapdh present in RNA isolated from the lungs of three mice per group. (E) Quantification of mRNA levels of SP pneumolysin (Ply), endonuclease EndA, and neuraminidases NanA and NanB in 1918+SP and SP-alone infected lung tissue using RT-qPCR analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 2−ΔCt values of each virulence factor relative to 16S rRNA present in RNA isolated from the lungs of three mice per group. *p<0.05 or **p=0.05 by two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test.

Increased bacterial load and SP virulence factor expression during coinfection

Expression of influenza virus M gene RNA and bacterial 16S rRNA in lungs of infected mice was measured by RT-qPCR. The lungs of 1918 virus alone infected mice had consistent viral loads throughout the time-course (Fig. 1C). Mice exposed to 1918 virus followed by SP had similar viral levels at 4 days post-1918 (day +1 post-SP), but significantly lower levels at days five and six post-1918 inoculation compared to mice exposed to virus alone (p<0.05). Bacterial levels were significantly higher in 1918+SP compared to SP-alone infected mice at days 4 and 5 post-1918 (days +1 and +2 post-SP), but equivalent at 6 d post-1918 (day +3 post-SP) (Fig. 1D). Detection of 16S rRNA in spleen tissue by RT-qPCR from both SP and 1918+SP mice provided evidence of bacteraemia on days 5 and 6 post-1918 (days +2 and +3 post-SP, respectively) (Fig. S1). The expression of several important SP virulence factor genes [22] were also measured by RT-qPCR and normalized to bacterial 16S rRNA (Fig. 1E), including pneumolysin (ply), endonuclease A (endA); and neuraminidases nanA and nanB. At day 4 to 6 post-1918 (day +1 to +3 post-SP), ply, endA, nanA and nanB RNA were detected in 1918+SP mice. In contrast, very low or undetectable levels of endA, nanA and nanB RNA were observed in SP-alone infected mice.

Bacterial coinfection significantly enhances lung pathology

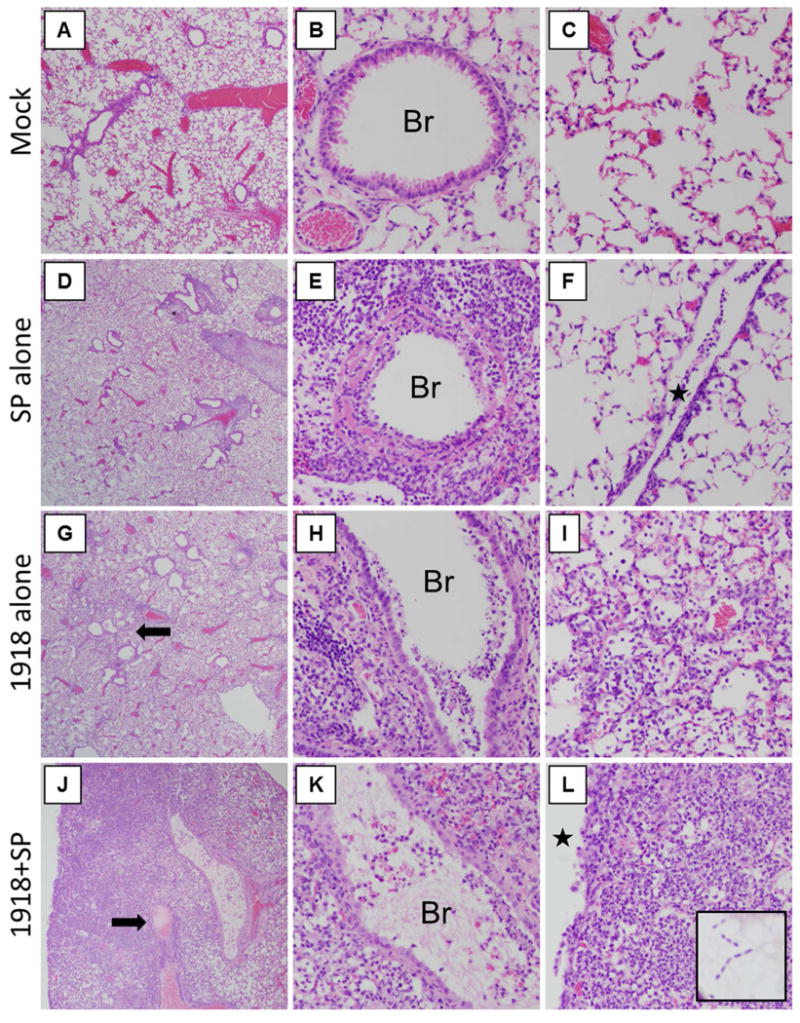

Lungs from mice were collected at days 3-6 post-1918 (days 0 to +3 post-SP) for histopathology. A unique gross pathological feature of the 1918+SP infected mice on days 4-5 (days +2 and +3 post-SP) was the presence of extensive fibrinous pleuritis with instances of fusion of the lungs to the chest wall and diaphragm. Lung pathology was evaluated in mice at days 4 to 6 following viral infection. In infected animals, histopathological changes increased from days 4 to 6, and day 6 pathology is described in here (Fig. 2). Mock-infected mice showed no histopathological changes in their lungs (Fig. 2A-C). SP-infected mice showed mild, focal changes (Fig. 2D-F), including focal acute bronchiolitis and rare microscopic foci of acute pleuritis. Gram-positive bacteria morphologically consistent with SP were occasionally observed within the focal lesions (not shown). 1918 virus-infected mice showed a more severe pathology, affecting >25% of the lung parenchyma (Fig. 2G-I), with widespread acute bronchiolitis and multifocal areas of acute alveolitis characterized by a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with prominent neutrophils in both alveolar airspaces and interstitium (Fig. 2I). Coinfected mice showed very severe histopathological changes affecting >50% of lung parenchyma (Fig. 2J-L) with consolidation consisting of an acute pneumonia, featuring alveolar airspaces packed with neutrophil- and macrophage-predominant inflammatory infiltrates, extensive acute suppurative pleuritis, widespread necrotizing bronchiolitis, and abundant fibrin thrombi in veins, venules, and capillaries (Fig. 2J, arrow).

Fig. 2. 1918 and SP coinfection greatly increases severity of lung pathology.

Lungs from mock and infected mice were harvested at 6 days post-1918 (3 d post-SP) and were stained with H&E. (A-C) Representative photomicrographs of mock-infected mice showing (A) no lung pathology, (B) normal bronchioles (Br), and alveoli without pathology. (D-F) Representative photomicrographs of SP-infected mice showing (D) focal, mild pathological changes, including (E) focal acute bronchiolitis (Br), and (F) rare foci of pleuritis (star). (G-I) Representative photomicrographs of 1918-infected mice showing (G) multifocal pathological changes including alveolitis (arrow) affecting >25% of lung parenchyma, (H) multifocal acute bronchiolitis (Br), and (I) an acute alveolitis with numerous mixed inflammatory cells in the airspaces and interstitium, including abundant neutrophils. (J-K) Representative photomicrographs of 1918-SP infected mice showing (J) widespread acute pneumonia with consolidation and abundant thrombi (arrow) affecting >50% of the lung parenchyma, (K) multifocal acute bronchiolitis (Br), and (L) an acute pneumonia pattern with alveolitis with numerous mixed inflammatory cells in the airspaces and interstitium, including abundant neutrophils, and extending into an acute pleuritis (star). (A, D, G, J original magnification ×20; B, C, E, F, H, I, K, L original magnification ×200).

Bacterial coinfection causes perturbations in inflammation-related coagulation homeostasis

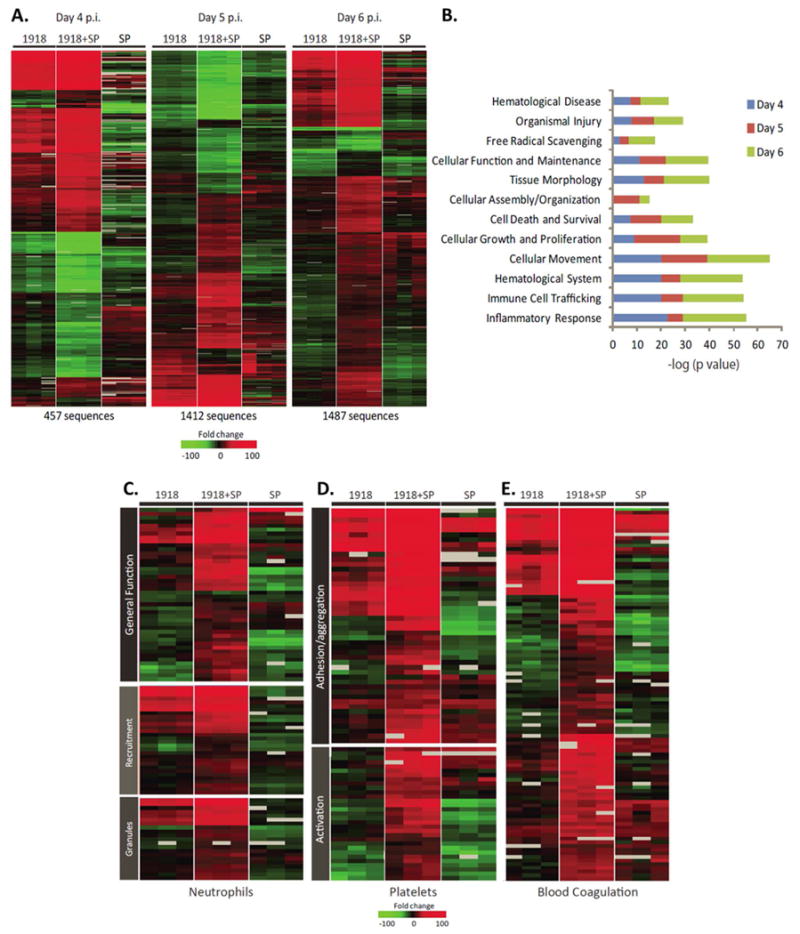

Global transcriptional profiling was performed on lung tissue mRNA at days 3-6 post-1918 (day 0 to +3 post-SP). For each experiment, mRNA from an individual infected animal was compared to mRNA from a pool of mock-infected mice (n= 4). Approximately 14 800 sequences showed a ≥2-fold change in expression (p<0.01) in at least one experimental group (Fig. S2). The expression levels of 457, 1412, and 1 487 transcripts differed significantly (≥2-fold, p< 0.01) between mice infected with 1918-alone and 1918+SP at days 4, 5, and 6, respectively, correlating with increased differences in disease pathology throughout the time-course. At day 4 post-1918 (day +1 post-SP), the direction of gene expression changes were similar between 1918 alone and 1918+SP, with enhanced magnitude of change generally observed in coinfected mice (Fig. 3A). Expression during SP-alone infection is shown for comparison. However, by days 5 and 6 post-1918 (day +2 and +3 post-SP) there were also increasingly larger groups of sequences that showed increased expression only in 1918+SP-infected mice.

Fig. 3. Coinfection of 1918 influenza virus and SP induces a unique host response compared to either pathogen alone.

(A) A standard t-test comparison was used to identify genes whose mRNA levels differed significantly (at least 2-fold difference in median expression level, p< 0.01) in lung tissue from 1918+SP versus 1918-infected mice. Each column represents gene expression data from an individual experiment comparing lung tissue from an infected animal relative to pooled tissue from mock infected mice (n=9). Red shows increased, green decreased, and black no change in mRNA levels in infected relative to uninfected mice. (B) Functional annotation analysis of genes differentially expressed between 1918+SP and 1918-infected mice at day 4 to 6 post-1918. (C-E) Differences in host response to 1918 and SP coinfection suggest perturbations in inflammation-related coagulation homeostasis. Expression profiles of transcripts involved in (C) neutrophil infiltration and activity, (D) platelet aggregation and (E) blood coagulation that are differentially expressed in 1918, SP, and 1918+SP infected mice at day 6 post viral infection. Each column represents gene expression data from an individual experiment comparing lung tissue from an infected animal relative to pooled tissue from mock mice (n=9). Red shows increased, green decreased, and black no change in mRNA levels in infected relative to uninfected mice.

Functional annotation of differentially expressed genes between 1918 and 1918+SP infected mice revealed enrichment of genes related to inflammatory response, immune cell trafficking, haematological system, and genes related to tissue injury (Fig. 3B). The distribution of enriched functional groups was generally consistent across all time points, with the exception of day 4 which showed higher enrichment of ROS scavenging and lower involvement of immune cell trafficking and inflammation, coinciding with a significantly higher bacterial burden (Fig. 1D). Examination of expression of an additional ∼700 inflammatory mediators revealed that while 1918+SP coinfection was associated with increased expression of genes relative to 1918-alone, differences were modest (Fig. S3). Furthermore, many inflammation-related genes that showed higher expression levels or were specifically increased in 1918+SP mice relative to 1918-alone infected mice were not increased in SP-alone mice (Fig. S3).

Many immune response-related genes that were either more highly expressed or uniquely expressed in 1918+SP mice at day 5 are involved in neutrophil recruitment/activation, platelet aggregation/activation and coagulation (Fig. 3C-E). Levels of the mRNA for certain chemokines and adhesion molecules mediating neutrophil infiltration (e.g., Ccl2, Ccl7, Cd177, and Itgam) were significantly higher in 1918+SP-infected mice relative to 1918-alone. In contrast, those for other chemokines and adhesion molecules (e.g., IL15, Ccl11, Ccl24, Itgb2, Ccrl2) were increased only in 1918+SP mice. Notably, many key neutrophil activation marker mRNAs were also either uniquely increased (including granule components Mpo, cathepsin G (Ctsg), Dao, Mmp9, Fcgr3 and Fpr2) or more highly increased (Mmp8, Fcgr1) in 1918+SP infected mice. Certain neutrophil-related genes (including Cleb1b, cathepsin G (Ctsg), F3, Pf4 and Itgb2) also function to promote platelet aggregation/activation. Levels for Proteinase 3 (Prtn3), encoding a serine protease that contributes to the proteolytic generation of antimicrobial peptides and also inhibits clearance of apoptotic neutrophils, promoting inflammation, were also increased (Fig. 3C).

Expression of genes associated with platelet aggregation included those from Gp1b-IX-V/GpVI-dependent platelet activation pathway (collagen 1, Itgb2, and glycoproteins Gp-1B alpha, Gp-1B beta, Gp-V, Gp-VI, and Gp-IX) (AQ: not all of these are approved mouse gene names), which plays a critical role in collagen-induced platelet aggregation and thrombus formation at sites of vascular injury, were also significantly higher in 1918+SP infected mice (Fig. 3D). Similarly, increased mRNA levels for other genes involved in platelet aggregation were observed in 1918+SP mice including platelet-activating factor receptor (Ptafr), thrombospondin s1 (Thbs1), platelet factor 4 (Pf4), a chemokine released from alpha granules of activated platelets, and purinergic receptor P2Y, G-protein coupled, 12 (P2ry12), a neutrophil-specific receptor. Pro-platelet basic protein (Ppbp), which protein activates neutrophils and stimulates the secretion of plasminogen activator, was increased only in 1918+SP mice.

Consistent with gene expression data supportive of enhanced platelet activity, increased expression of numerous coagulation cascade genes, including those for factors III, V, X, and XIII (Fig. 3E) was observed in coinfected mice. Levels for Tissue plasminogen activator (Plat), encoding the key enzyme responsible for converting plasminogen to plasmin and urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (Plaur) were also significantly induced only in coinfected mice. Concordantly, increased Plat expression was observed in 1918+SP mice by immunohistochemistry (Fig. S4). Increased expression of genes that inhibit platelets and coagulation was also observed, including tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 (F3pi2), Serpine1, Serpine3, annexin A3 (Anxa3) and phospholipase A2 group VII (Pla2g7). Similar to the observations for neutrophil-related genes, expression of the majority of genes involved in platelet function and coagulation were not increased in SP-alone mice.

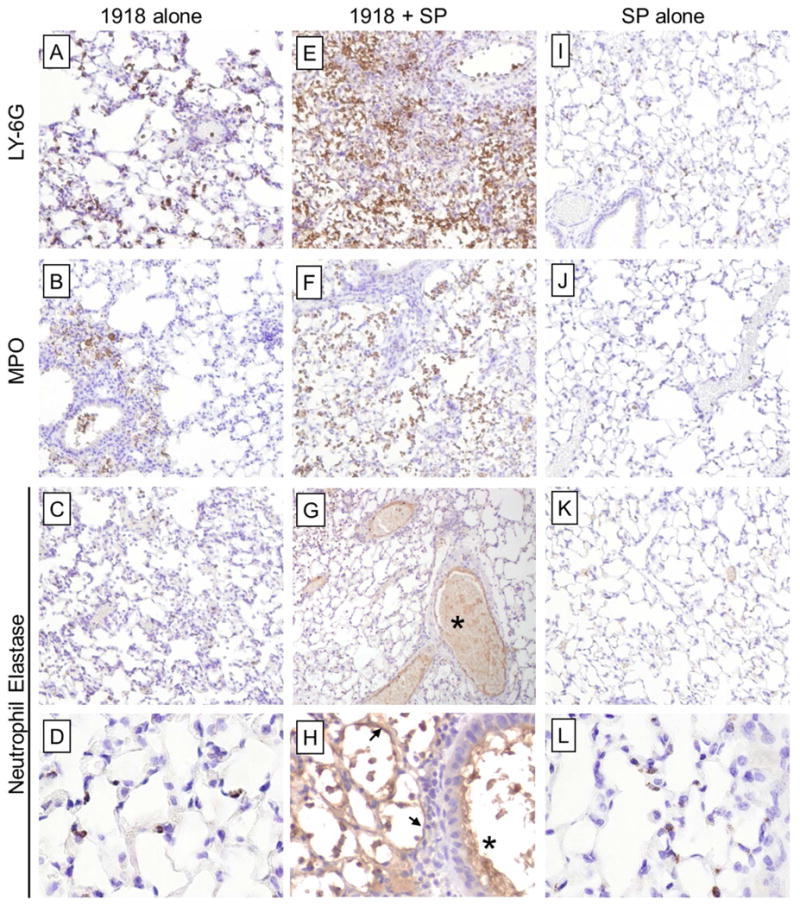

Neutrophil activation and deposition of elastase onto vascular endothelial cells during coinfection

To further examine the neutrophil infiltration and activation, mouse lung sections were immunostained for Ly6G, myeloperoxidase (MPO), and neutrophil elastase (ELANE), key enzyme constituents of azurophilic granules in neutrophils. 1918-SP-coinfection produced extensive and progressive infiltration of LY6G-positive neutrophils with particularly high expression in lung regions with the greatest histopathological changes, in contrast to the lower, but clearly detectable, accumulation of LY6G-positive neutrophils in mice infected with 1918- or SP-alone (Fig. 4). In coinfected mice, cellular infiltrates expressed high levels of MPO and ELANE compared to lower expression in mice infected with 1918- or SP-alone. The 1918+SP infected mice also showed increased extracellular ELANE deposition along the endothelium of many blood vessels consistent with an enhanced degranulation response. Similarly, ELANE was also prominently expressed on alveolar and bronchiolar epithelium and neutrophils in 1918+SP infected mice (Fig. 4H). Immunohistochemical time courses for Ly6G, MPO, ELANE and the monocyte/neutrophil marker CD11b are shown in Figs. S5-S8.

Fig. 4. 1918 and SP coinfection induces extensive neutrophil infiltration and activation.

Mouse lung sections harvested at 6 d post-infection with influenza virus (3 d post-infection with SP in coinfection groups) were stained for Ly6G, a specific neutrophil marker, MPO, and neutrophil elastase (ELANE). (A-D) 1918 alone and (I-L) SP alone induced detectable increases in Ly6G-positive neutrophils with low level expression of MPO and ELANE localized primarily around large airways and blood vessels. (E-H) 1918-SP infected mice showed extensive infiltration of Ly6G-positive neutrophils with high expression levels of MPO and ELANE. Extracellular ELANE deposition was also noted on the inner lining of many large and medium-sized blood vessels (asterisk). (H) ELANE-positive intra-alveolar neutrophils and alveolar walls (black arrows) were observed in 1918-SP infected mice whereas with (D) 1918 and (L) SP infection ELANE-positive neutrophils remained within the interstitium. (A-C, E-G, I-K original magnification ×100; D, H, L original magnification ×600).

Activation of coagulation and vascular thrombogenesis in lungs of coinfected mice

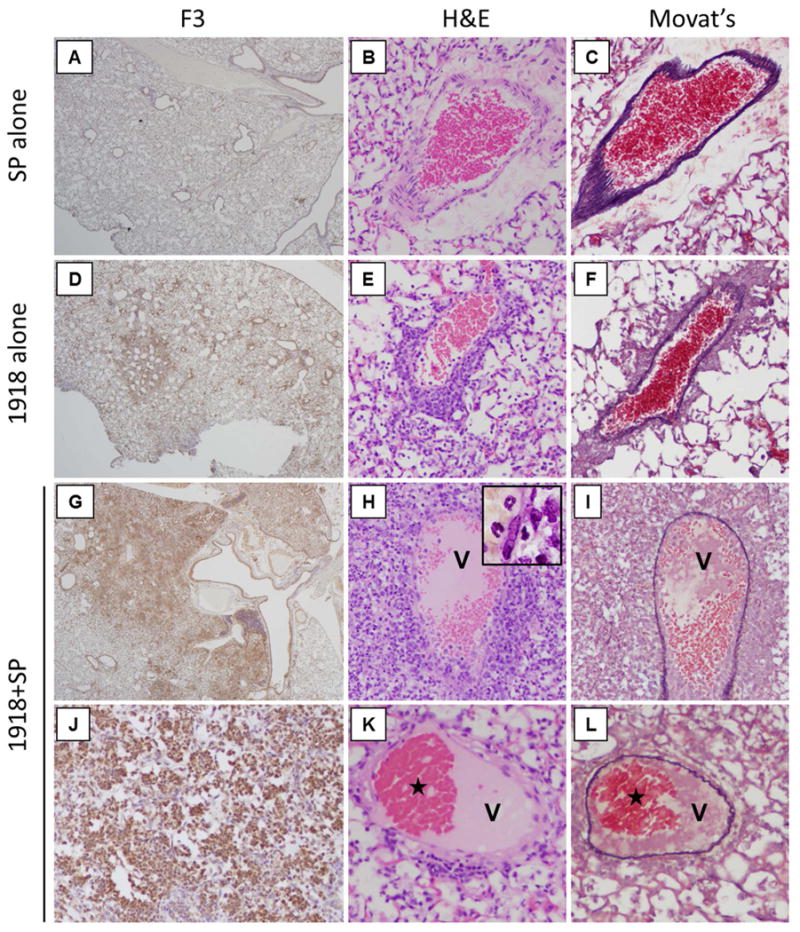

Immunohistochemical staining of day 6 mouse lung sections with F3 revealed differential staining between groups (Fig. 5). SP-infected mice showed only minimal F3 staining (Fig. 5 A), especially around regions of bronchiolitis, both in respiratory epithelial cells and inflammatory cells. No evidence of vascular pathology was noted (Fig. 5 B-C). 1918-infected mice showed widespread F3 staining in areas of bronchiolitis and alveolitis (Fig. 5 D). Vessels showed prominent perivascular inflammatory cell infiltrates (Fig. 5 E-F) without evidence of thrombus formation. In marked contrast, coinfected mice showed extensive and very prominent F3 staining throughout the lungs, especially in areas of acute pneumonia, bronchiolitis, and pleuritis (Fig. 5G & J). Unlike the other groups, there were also abundant thrombotic lesions in small veins, venules and capillaries (Fig. 5H, I, K, L), consisting of fibrinous thrombi, sometimes with recanalization (Fig. 5 K, L). Examination of F3 expression over the infection time course revealed marked accumulation of F3 staining in the lungs of coinfected mice, and to a lesser extent in the 1918- and SP-infected mice (Fig. S9). Similarly, 1918+SP-coinfection also resulted in prominent thrombin staining (Fig. S10).

Fig. 5. 1918 and SP coinfection causes significant and widespread expression of F3 and pulmonary thrombosis in mice.

Lung sections from SP-infected, 1918-infected, and coinfected mice were immunostained for F3 and pulmonary vessels were examined for pathological changes. (A-C) Representative photomicrographs of SP-infected mice showing (A) focal F3 staining predominantly around bronchioli, and no vascular pathology. (B-C) serial sections show (B) a normal venule without perivascular inflammation or thrombosis stained with H&E and (C) stained with Movat's stain to highlight elastin. (D-F) Representative photomicrographs of 1918-infected mice showing (D) multifocal prominent F3 staining around bronchioli and areas of alveolitis. Vessels show perivascular inflammation but no thrombi, (E) H&E and (F) Movat's stain. (G-L) Representative photomicrographs of coinfected mice showing (G) very prominent and diffuse F3 staining around bronchioli and (J) areas of acute pneumonia. (H, I, K, L) Abundant fibrin thrombi are seen in venules (V). Perivascular inflammation was prominent in (H) H&E stain and the thrombus was highlighted with (I) Movat's stain. Another thrombus (K, L) showed recanalization (stars) seen in both (K) H&E and (L) Movat's stain. (A, D, G original magnification ×20; B, C, E, F, H, I, J, K, L original magnification ×200).

Extensive expression of F3 and occurrence of vascular thrombi in 1918 pandemic autopsy samples with bacterial coinfection

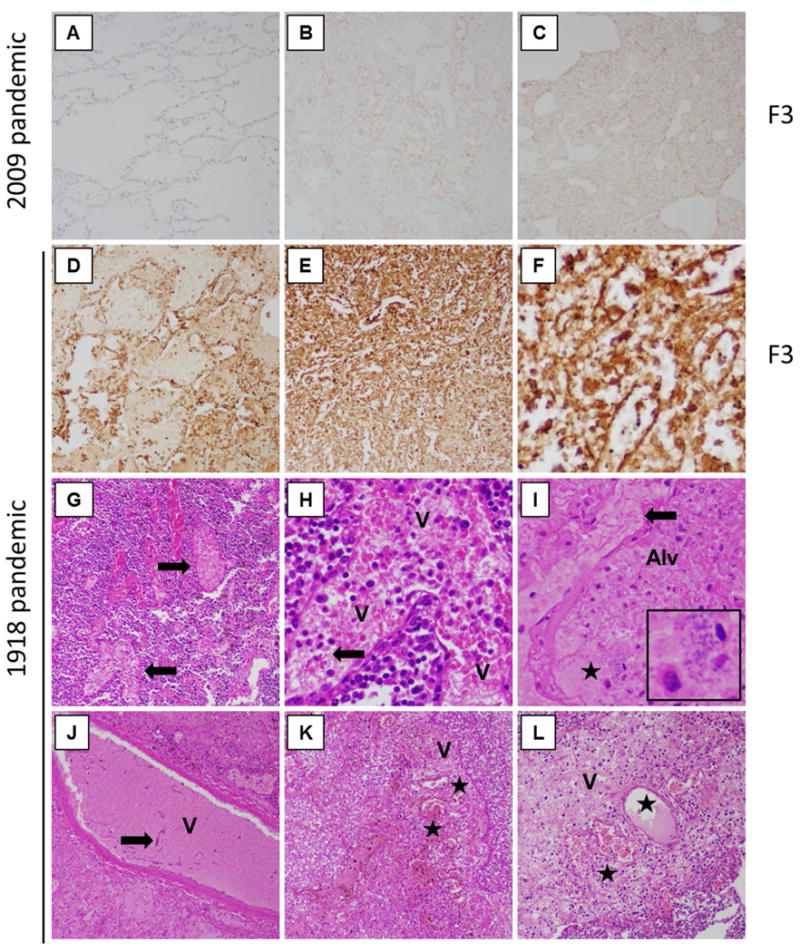

Postmortem lung tissue sections from victims of the 1918 [3] and 2009 [21] H1N1 influenza pandemics were subsequently examined for correlative changes. F3 showed little to no immunostaining in normal lung (Fig. 6A), and only minimal levels in two 2009 pandemic autopsy cases (Fig. 6B-C). Interestingly, two 1918 pandemic autopsy cases showed marked F3 expression (Fig. 6D-F), very similar to F3 in mouse lung sections from the coinfected group (Fig. 5G & J). As in coinfected mouse lungs, F3 staining was observed in monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and also epithelial cells (Fig. 6F). Examination of ten 1918 autopsy cases showed abundant small vessel thrombosis in most cases, as previously described in 1918 [17,18]. Fibrinous thrombi were commonly observed in small veins, venules, and capillaries on examination of H&E stained lung sections (Fig. 6G-L). Some thrombi showed evidence of organization with ingrowth of fibroblasts, collagen deposition (Fig. 6J), or recanalization (Fig. 6K & L).

Fig. 6. Abundant and extensive expression of F3 and widespread pulmonary thrombosis in coinfected 1918 human autopsy case material.

(A-F) Post mortem lung sections were stained for F3. (A) Normal control lung showed little-to-no F3 staining. (B-C) Mild-to-moderate F3 staining was observed in two 2009 pandemic influenza post mortem cases, with staining observed in both inflammatory and epithelial cells. (B) 2009 pandemic case 14, and (C) 2009 pandemic case 1, as previously described in Gill et al. 2010 Table 2 [21]. (D-F) F3 staining of 1918 pandemic post mortem cases showing very prominent F3 staining observed in both inflammatory and epithelial cells. (D) 1918 pandemic case 19180925b, and (E-F) 1918 pandemic case 19180924d, as previously described in Sheng et al. 2011 Supplementary Table 1 [3]. (G-L) Abundant small venule thrombi are observed 1918 pandemic post mortem cases. (G) 1918 case 19180926b showing several venules with fibrin thrombi, arrows. (H) Same case as (G) showing a venule, V, filled with thrombus consisting of erythrocytes admixed with fibrin strands, arrow). (I) 1918 case 19181017 showing an organizing thrombus with prominent fibrin in an interstitial capillary (arrow) next to an alveolus, alveoli filled with oedema, inflammatory cells, and bacteria morphologically consistent with SP (star) and inset. (J) Same case showing a venule, V, with a thrombus with early organization with fibroblasts, arrow, within the thrombus. (K) 1918 case 19180924d (same as in F) showing an organizing thrombus in a venule, denoted by V, with recanalized lumina (denoted by stars). (L) 1918 case 19181008d showing an organizing thrombus in a small vein, V, with recanalized lumina, stars. (A-E original magnification ×20; G, I, J, K, L original magnification ×200; F, H original magnification ×400).

Discussion

In this study, SP secondary infection following 1918 pandemic virus was shown to enhance lung pathology, damage endothelial cells and activate coagulation in mice. These attributes of 1918+SP coinfection fulfil the requirements for thrombosis in Virchow's triad of reduced flow, hypercoagulability, and endothelial damage (Fig. S11). Significantly, findings from the mouse model were validated in 1918 human lung autopsy samples from two SP-positive cases. These cases showed intense and widespread F3 staining in neutrophils, monocytes, alveolar macrophages, as well as epithelial and endothelial cells accompanied by numerous small vessel thrombi. In contrast, minimal F3 staining was observed in SP- or Streptococcus pyogenes-positive 2009 pandemic H1N1 autopsy samples. Retrospective analysis of a previously published study from SP coinfected 1918 and 2009 pandemic H1N1 autopsy samples [15] revealed that of 292 coagulation-related genes identified, 47% were more abundant in the 1918 samples, including, factor VIII (F8), von Willebrand factor (VWF), PLAUR and PLAT; while only 6% of these gene transcripts were more abundant in the 2009 autopsy samples. The findings of widespread thrombi and extensive expression of clotting factors strongly support activation of coagulation during 1918+SP coinfection and may explain increased fatalities associated with secondary bacterial infections during the 1918 influenza pandemic.

Increased bacterial and/or viral loads during coinfection have previously been associated with enhanced severity of influenza virus and SP coinfection [4,5,10]. Early increases in bacterial burden in 1918+SP infected mice suggests that virus-mediated damage to the respiratory epithelium increased the initial bacterial colonization, possibly by exposing receptors for bacterial attachment [23]. Indeed, higher levels of Ptafr, the product of which plays a role in adhesion and invasion of S. pneumonia, were observed in coinfected animals [24]. Lower levels of 1918 virus during SP coinfection are likely related to loss in tissue viability. Despite similar bacterial loads in the lungs of SP and 1918+SP infected mice at day 3 post-SP infection, there was significantly higher expression of SP virulence factors in 1918+SP mice, including endA, nanA and nanB, and ply. EndA degrades the DNA scaffold of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and allow bacteria to spread from the upper airways to the lungs and into the blood-stream during pneumonia [25]; nanA and nanB play important roles in colonization [26] and ply has been reported to activate macrophages and neutrophils and has haemolytic and cytotoxic activities [27,28]. Differential expression of bacterial virulence factors during viral coinfection is intriguing and future studies will characterize SP virulence factor expression and roles in pathology during coinfection, which may provide insight into how viral infection-mediated immune responses modulate bacterial survival responses.

Pathology, transcript profiling, and immunohistochemical analysis of lung tissue all support perturbation of immune-related coagulation homeostasis and thrombogenesis during 1918+SP coinfection. Importantly, acute haemorrhage and thrombus formation were common findings in fatal 1918 influenza cases [3,18], suggesting the mouse model accurately reflects the underlying pathology observed in human disease. Furthermore, neutrophil transepithelial migration contributes to pulmonary oedema [29], another common finding associated with fatal 1918 infections [3]. Following 1918 influenza virus infection, the lung may be primed for perturbation of immune-related thrombosis following secondary bacterial infection. First, 1918 influenza virus is associated with enhanced damage to the respiratory epithelium relative to other influenza viruses [18]. Second, 1918 viral infection results in extensive lung infiltration of neutrophils in animals [19,30] and 1918 influenza autopsy cases [3]. It is possible that the combination of viral and bacterial stimuli result in a unique functional neutrophil phenotype, which is supported by gene expression and immunohistochemistry data of enhanced activation of neutrophils during coinfection. Increasingly, neutrophils are thought to play a key role in the interaction between inflammatory and thrombotic pathways [31-34]. The neutrophil serine proteases ELANE and cathepsin G, both of which had increased mRNA expression in 1918+SP-infected mice, are known to promote coagulation and intravascular thrombus growth through proteolysis of the coagulation suppressor tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) [34]. While infiltration of neutrophils and F3 expression is observed in mice infected with 1918 alone, there appears to be less activation of neutrophils as evidenced by less intense staining of MPO and ELANE and lower expression of numerous genes associated with neutrophil activation compared to coinfection. Exposure to SP may subsequently cause activation of extensive population of neutrophils already present in the lung, initiating the coagulation cascade, possibly through elastase/cathepsin G-mediated cleavage of TFPI. This process may further be amplified by bacteria-induced NETs, which are thought contribute to thrombosis by providing the scaffold for fibrin deposition and platelet aggregation/activation [35,36]. Therefore, while 1918-infection alone may prime the lung for thrombogenesis, in the absence of SP-induced activation of neutrophils and possibly NETs, expression of F3 and presence of neutrophils may not be sufficient for initiation of the coagulation cascade and thrombus formation. The absence of thrombus in SP-alone infected mice can be attributed to lack of significant F3 expression and extensive infiltration of neutrophils. While SP infection alone could be associated with mortality, this may be due to different pathological mechanisms such as bacteraemia as 16S rRNA was detected in spleens of some mice as early as 2 days post-SP inoculation in both SP-alone and 1918+SP infected groups.

Secondary bacterial infections played a major role in the high mortality of the 1918 influenza pandemic, but the underlying pathophysiology responsible has not been previously investigated. While much has been learned about the genetic determinants responsible for the extreme virulence of 1918 influenza viral infection in animal models, particularly the role of the 1918 HA gene in neutrophil activation and recruitment [19,37] and the role of the viral protein PB1-F2 in susceptibility to secondary bacterial infection [38], this study represents the first investigation of the reconstructed 1918 virus and bacterial coinfection. Coinfection-induced pulmonary thrombosis would exacerbate vascular leak and alveolar oedema due to passive congestion limiting compensatory ventilation responses contributing to severe hypoxia and death (and possibly to the unusual frequency of rapid-onset cyanosis reported in 1918). Experiments evaluating efficacy of targeting neutrophil activation and/or components of the coagulation pathway to reduce severity of pneumonia during influenza viral and bacterial coinfection could open new treatment modalities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institutes of Health and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. K.A.W. and R.E.K. were supported by Defense Threat Reduction Agency contract HDTRA-1-08-C-0023. We thank Dr. David Morens at NIAID/NIH for helpful discussions. Animal care was performed by the Comparative Medicine Branch, NIH/NIAID.

Abbreviations

- SP

Streptococcus pneumoniae

- F3

tissue factor

- ELANE

elastase, neutrophil expressed

- HA

Hemagglutinin

- IFN

Interferon

- 1918 virus

1918 H1N1 influenza virus

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- CFU

Colony forming units

- PFU

Plaque forming units

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- NETs

neutrophil extracellular traps

- Ptafr

platelet-activating factor receptor

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest and the research sponsors played no role in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report and in the decision to submit the report for publication

Author contributions. Conceptualization, KAW, FD, JKT, and JCK; Methodology, KAW, JKT, and JCK; Formal analysis, KAW and JCK; Investigation, KAW, FD, ZMS, JK, LMS, REK, DSC, JKT and JCK; Writing – Original Draft, KAW and JC; Writing – Review & Editing, KAW, FD, JK, DSC, BTG, JKT, and JCK; Visualization, KAW, FD, JKT, and JCK; Resources, JKT; Supervision, JKT and JCK.

References

- 1.Johnson NP, Mueller J. Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918-1920 “Spanish” influenza pandemic. Bull Hist Med. 2002;76:105–115. doi: 10.1353/bhm.2002.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS. Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:962–970. doi: 10.1086/591708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheng ZM, Chertow DS, Ambroggio X, et al. Autopsy series of 68 cases dying before and during the 1918 influenza pandemic peak. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:16416–16421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111179108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCullers JA. Insights into the interaction between influenza virus and pneumococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:571–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCullers JA. The co-pathogenesis of influenza viruses with bacteria in the lung. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:252–262. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tashiro M, Ciborowski P, Klenk HD, et al. Role of Staphylococcus protease in the development of influenza pneumonia. Nature. 1987;325:536–537. doi: 10.1038/325536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tashiro M, Ciborowski P, Reinacher M, et al. Synergistic role of staphylococcal proteases in the induction of influenza virus pathogenicity. Virology. 1987;157:421–430. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCullers JA. Do specific virus-bacteria pairings drive clinical outcomes of pneumonia? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:113–118. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCullers JA, McAuley JL, Browall S, et al. Influenza enhances susceptibility to natural acquisition of and disease due to Streptococcus pneumoniae in ferrets. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1287–1295. doi: 10.1086/656333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kash JC, Walters KA, Davis AS, et al. Lethal synergism of 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus and Streptococcus pneumoniae coinfection is associated with loss of murine lung repair responses. MBio. 2011;2 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00172-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iverson AR, Boyd KL, McAuley JL, et al. Influenza virus primes mice for pneumonia from Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:880–888. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Memoli MJ, Tumpey TM, Jagger BW, et al. An early ‘classical’ swine H1N1 influenza virus shows similar pathogenicity to the 1918 pandemic virus in ferrets and mice. Virology. 2009;393:338–345. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobasa D, Jones SM, Shinya K, et al. Aberrant innate immune response in lethal infection of macaques with the 1918 influenza virus. Nature. 2007;445:319–323. doi: 10.1038/nature05495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kash JC, Tumpey TM, Proll SC, et al. Genomic analysis of increased host immune and cell death responses induced by 1918 influenza virus. Nature. 2006;443:578–581. doi: 10.1038/nature05181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao YL, Kash JC, Beres SB, et al. High-throughput RNA sequencing of a formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded autopsy lung tissue sample from the 1918 influenza pandemic. The Journal of pathology. 2013;229:535–545. doi: 10.1002/path.4145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kash JC, Xiao Y, Davis AS, et al. Treatment with the reactive oxygen species scavenger EUK-207 reduces lung damage and increases survival during 1918 influenza virus infection in mice. Free radical biology & medicine. 2014;67:235–247. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LeCount ER. Disseminated necrosis of the pulmonary capillaries in influenzal pneumonia. J Amer Med Assoc. 1919;72:1519–1520. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taubenberger JK, Morens DM. The pathology of influenza virus infections. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:499–522. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.154316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qi L, Davis AS, Jagger BW, et al. Analysis by single-gene reassortment demonstrates that the 1918 influenza virus is functionally compatible with a low-pathogenicity avian influenza virus in mice. Journal of virology. 2012;86:9211–9220. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00887-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gill JR, Sheng ZM, Ely SF, et al. Pulmonary pathologic findings of fatal 2009 pandemic influenza A/H1N1 viral infections. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2010;134:235–243. doi: 10.5858/134.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dockrell DH, Whyte MK, Mitchell TJ. Pneumococcal pneumonia: mechanisms of infection and resolution. Chest. 2012;142:482–491. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plotkowski MC, Puchelle E, Beck G, et al. Adherence of type I Streptococcus pneumoniae to tracheal epithelium of mice infected with influenza A/PR8 virus. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134:1040–1044. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.5.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iovino F, Brouwer MC, van de Beek D, et al. Signalling or binding: the role of the platelet-activating factor receptor in invasive pneumococcal disease. Cell Microbiol. 2013;15:870–881. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beiter K, Wartha F, Albiger B, et al. An endonuclease allows Streptococcus pneumoniae to escape from neutrophil extracellular traps. Curr Biol. 2006;16:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brittan JL, Buckeridge TJ, Finn A, et al. Pneumococcal neuraminidase A: an essential upper airway colonization factor for Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2012;27:270–283. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2012.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell TJ, Dalziel CE. The biology of pneumolysin. Sub-cellular biochemistry. 2014;80:145–160. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-8881-6_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Preston JA, Dockrell DH. Virulence factors in pneumococcal respiratory pathogenesis. Future microbiology. 2008;3:205–221. doi: 10.2217/17460913.3.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayadas TN, Cullere X, Lowell CA. The multifaceted functions of neutrophils. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:181–218. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-164023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perrone LA, Plowden JK, Garcia-Sastre A, et al. H5N1 and 1918 pandemic influenza virus infection results in early and excessive infiltration of macrophages and neutrophils in the lungs of mice. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000115. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andrews RK, Arthur JF, Gardiner EE. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and the role of platelets in infection. Thromb Haemost. 2014;112:659–665. doi: 10.1160/TH14-05-0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gardiner EE, Andrews RK. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and infection-related vascular dysfunction. Blood Rev. 2012;26:255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kambas K, Mitroulis I, Ritis K. The emerging role of neutrophils in thrombosis-the journey of TF through NETs. Front Immunol. 2012;3:385. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Massberg S, Grahl L, von Bruehl ML, et al. Reciprocal coupling of coagulation and innate immunity via neutrophil serine proteases. Nat Med. 2010;16:887–896. doi: 10.1038/nm.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clark SR, Ma AC, Tavener SA, et al. Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nat Med. 2007;13:463–469. doi: 10.1038/nm1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fuchs TA, Brill A, Duerschmied D, et al. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:15880–15885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005743107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kash JC, Basler CF, Garcia-Sastre A, et al. Global host immune response: pathogenesis and transcriptional profiling of type A influenza viruses expressing the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase genes from the 1918 pandemic virus. Journal of virology. 2004;78:9499–9511. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9499-9511.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McAuley JL, Hornung F, Boyd KL, et al. Expression of the 1918 influenza A virus PB1-F2 enhances the pathogenesis of viral and secondary bacterial pneumonia. Cell host & microbe. 2007;2:240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.