Abstract

Background

Children who wear hearing aids may be at risk for further damage to their hearing from over-amplification. Previous research on amplification-induced hearing loss has included children using linear amplification or simulations of predicted threshold shifts based on nonlinear amplification formulae. A relationship between threshold shifts and the use of nonlinear hearing aids in children has not been empirically verified.

Purpose

The purpose of the study was to compare predicted threshold shifts from amplification to longitudinal behavioral thresholds in a large group of children who wear hearing aids to determine the likelihood of amplification-induced hearing loss.

Research design

An accelerated longitudinal design was used to collect behavioral threshold and amplification data prospectively.

Study sample

Two-hundred and thirteen children with mild to profound hearing loss who wore hearing aids were included in the analysis.

Data collection and analysis

Behavioral audiometric thresholds, hearing aid outputs and hearing aid use data were collected for each subject across four study visits. Individual ear- and frequency-specific safety limits were derived based on the Modified Power Law to determine the level at which increased amplification could result in permanent threshold shifts. Behavioral thresholds were used to estimate which children would be above the safety limit at 500 Hz, 1000 Hz, 2000 Hz and 4000 Hz using thresholds in dB HL and then in dB SPL in the ear canal. Changes in thresholds across visits were compared for children who were above and below the safety limits.

Results

Behavioral thresholds decreased across study visits for all children, regardless of whether or not their amplification was above the safety limits. The magnitude of threshold change across time corresponded with changes in ear canal acoustics as measured by the real-ear-to-coupler difference.

Conclusions

Predictions of threshold changes due to amplification for children with hearing loss did not correspond with observed changes in threshold over across two to four years of monitoring amplification. Use of dB HL thresholds and predictions of hearing aid output to set the safety limit resulted in a larger number of children being classified as above the safety limit than when safety limits were based on dB SPL thresholds and measured hearing aid output. Children above the safety limit for the dB SPL criteria tended to be fit above prescriptive targets. Additional research should seek to explain how the Modified Power Law predictions of threshold shift overestimated risk for children who wear hearing aids.

Keywords: hearing aids, children, pediatrics, safety limits, modified power law, audiogram, hearing loss, amplification, temporary threshold shifts, permanent threshold shifts

Introduction

The purpose of providing amplification to children who are hard of hearing is to make speech and other important acoustic cues audible to minimize the negative developmental consequences of hearing loss. Children who are hard of hearing who have greater speech audibility through their hearing aids have better speech and language outcomes (Tomblin et al. 2014) and speech recognition (Davidson & Skinner, 2006; Scollie, 2008; McCreery et al. in review2015) than peers with poorer audibility. The American Academy of Audiology Pediatric Amplification Guidelines (AAA; 2013) recommend that the output of a child’s hearing aids be individually verified to ensure that speech is audible and that the output of the hearing aid is below the levels where discomfort or permanent damage to hearing may occur. Threshold data collected from children with linear amplification (Macrae, 1991, 1993, 1994, 1995) demonstrated that some children may be at risk for deterioration in hearing thresholds from amplification that exceeded safe levels. More recently, predictions of amplification-induced hearing loss were modelled using two frequently-used prescriptions for nonlinear amplification in children (Ching et al. 2013a). Model predictions suggested that children fit to Desired Sensation Level multi-stage input/output (DSL m i/o, Version 5.0a; Scollie et al. 2005) prescriptive targets may be at-risk for permanent changes in hearing due to the amount of gain prescribed. The predictions of the model presented by Ching and colleagues have yet to be evaluated empirically. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the risk of amplification-induced hearing loss in a large group of children fit to DSL prescriptive targets who were followed as part of the Outcomes of Children with Hearing Loss (Moeller & Tomblin, 2015) longitudinal study.

A series of studies by Macrae (1991; 1993; 1994; 1995) highlighted the risk of hearing loss from over-amplification for a small group of children with mild to severe sensorineural hearing loss. Macrae (1991) presented serial audiometric threshold data for eight children (ages not reported) with sensorineural hearing loss who used a body-worn hearing aid in one ear between 10–14 hours per day. The range of outputs of the body-worn hearing aids was estimated to be 17–31 dB higher than prescribed levels across subjects. Each child had a history of stable audiometric thresholds prior to amplification. Following over-amplification, changes in threshold of 10–25 dB were observed at multiple audiometric frequencies and were only present in the amplified ear. Thresholds shifts occurred between 1–8 years from the onset of amplification. The over-amplification was at least partially attributed to high volume control settings. The magnitude of threshold changes was consistent with predictions of the Modified Power Law (MPL; Humes & Jesteadt, 1991). Because the presence and degree of existing hearing loss can influence the magnitude of the threshold shift from excessive noise exposure, the MPL can be used estimate the threshold shift and safety limits for listeners who already have sensorineural hearing loss.

The MPL model presented by Macrae (1994) is based on data that suggest that exposure to high levels of sound for durations up to eight hours in a day contribute to temporary threshold shifts (TTS; Mills, 1982). Exposures greater than 8 hours do not increase the likelihood of TTS, so the maximum amount of TTS that occurs in a day is referred to as the asymptotic threshold shift (ATS). The amount of ATS that can result in permanent threshold shifts (PTS) was formalized by Macrae (1994). The safety limit is the amount of ATS that can occur without PTS and varies as a function of degree of hearing loss. The safety limits decrease as degree of hearing loss increases. Unfortunately, the prescribed sound level and amount of gain required to make speech audible with amplification also increase with increasing degree of hearing loss, which could lead to a potential trade-off between making speech audible and preventing amplification-related PTS. Subsequent research by Macrae extended the findings of the MPL for predicting TTS after short-term exposure to over-amplification for a single subject (Macrae, 1993), recommending safety limits to avoid PTS for different frequencies and degrees of hearing loss (Macrae, 1994) and linking PTS to ATS (Macrae, 1995).

While these findings provided a comprehensive set of predictions that were useful in minimizing the potential for progressive hearing loss from over-amplification, several developments in amplification may limit the applicability of these results for children who are hard of hearing today. The results from studies by Macrae were based on data or predictions for linear amplification, while current amplification and prescriptive formulae for children are typically nonlinear. Most hearing aids fit for children use some form of amplitude compression (often wide dynamic range compression) to limit the amount of gain provided as the input level of the hearing aid increases (see McCreery et al. 2012 for a review). A hearing aid that was fit to provide gain based on a nonlinear prescriptive formula such as DSL v.5 (Scollie et al. 2005) or National Acoustics Laboratories NAL-NL2 (Keidser et al. 2011) produces less gain as the input level to the hearing aid increases compared to a linear hearing aid at the same input level. Reduced gain for high input levels with nonlinear amplification means a lower and potentially safer overall output level for the same input level. Among nonlinear prescriptive formulae, there are differences between the amount of gain provided to higher input levels. DSL v5 generally provides more gain at high input levels than NAL-NL2.

Ching and colleagues (2013a) extended the work of Macrae to nonlinear amplification by developing updated predictions for ATS and safety limits based on the prescribed gains for DSL v5 and NAL-NL2 prescriptive formulae. First, fifty-seven audiograms from children who participated in a longitudinal study of development in children with hearing loss were used to generate predictions of ATS based on the simulated prescribed outputs from DSL v.5 and NAL-NL2. Predictions of ATS were also generated for hypothetical audiograms with flat and sloping configurations over a range of degrees of hearing loss from mild to profound to generate safety limits for each prescriptive formula. Modeled data based on the fifty-seven audiograms from children indicated that both DSL v.5 and NAL-NL2 prescriptions resulted in the same hypothetical threshold shift for average speech input levels. For high input levels, the predicted threshold shifts were higher for DSL v.5 than NAL-NL2 at three of four frequencies, based on the fact that DSL v.5 prescribes more gain than NAL-NL2. For flat and sloping audiograms, simulations suggested that significant threshold shifts were unlikely to occur for individuals with thresholds less than 90 dB HL for average or high input levels with the NAL-NL2 prescription. With the DSL v.5 prescription, threshold shifts were predicted to occur for individuals with thresholds greater than 70 or 75 dB HL (depending on the frequency) due to relatively higher gains prescribed for high input levels compared to NAL-NL2. Given the lack of significant differences reported between the two prescriptions for speech and language outcomes (Ching et al. 2013b), the potential for threshold shifts with DSL v.5 was cited as justification to use the NAL-NL2 formula with children who wear hearing aids.

However, several aspects of the modelled threshold shift predictions from Ching et al. (2013a) should be evaluated prior to recommending changes in hearing aid prescription for children. First, the large number of children fit with hearing aids set to DSL targets in North America (McCreery, Bentler & Roush, 2013) should allow for empirical confirmation of the models that predict threshold shift will occur. Furthermore, the safety limits proposed by Ching and colleagues are referenced to dB HL, but dB SPL in the ear canal can vary by as much as 15–20 dB across children due to differences in ear canal volume (Bagatto et al. 2002; Bagatto et al. 2005). Some children with hearing levels in the moderate range who have large real-ear-to-coupler differences (RECD) may also be at-risk for over-amplification due to higher SPL levels in the ear canal. Any empirical evaluation of safety limits for amplification should incorporate individual differences in ear canal SPL.

Individualized estimates of ear canal SPL affect predictions of over-amplification in two ways. First, any safety limits that are developed based on predictions would be more accurate when considering the individual variability in ear canal SPL for children who have the same dB HL audiogram. Children with a smaller ear canal and larger RECD will have higher ear canal SPL levels than peers with the same dB HL threshold and a larger ear canal and smaller RECD. Individual differences in ear canal SPL can affect the potential risk of over-amplification, but have not been considered directly in previously published safety limits. Second, the decrease in RECD as the child grows and their ear canal increases in volume will result in a reduction in ear canal SPL. In dB HL, the child’s thresholds will increase (become poorer) over time if measured with earmolds or insert earphones because the effective ear canal SPL delivered by the transducer will decrease as the ear canal volume grows. Nonetheless, risk criteria based on the audiometric threshold in dB HL may be easier to apply clinically and may have utility for predictions of threshold shift. In the current study, ATS were estimated using both dB HL and dB SPL thresholds to estimate the number of children who are likely to exceed safety limits for each approach.

Predicting the potential for amplification-induced progression of hearing loss must also take into account the variability in hearing aid output that has been observed in infants and children. Many infants and young children who are hard of hearing have hearing aids that are set below prescribed values (McCreery, Bentler & Roush, 2013), particularly children with severe-to-profound hearing loss who may be at the greatest risk for over-amplification (Strauss & van Dijk, 2008). Simulations of over-amplification risk that assume that prescriptive targets can be matched for children with the greatest degrees of hearing loss may over-estimate the risk of amplification-induced hearing loss in children, simply because the prescribed gain cannot be achieved. The variability in the proximity of the hearing aid output to prescriptive target is therefore a potentially important factor for estimating the actual risks of over-amplification in children. Children with hearing aid fittings that provide less gain than prescribed would be less likely to have significant ATS, even if their predictions of hearing aid output based solely on prescription and the dB HL audiogram suggest that they may be at-risk.

Previous studies of over-amplification risk in children have also been limited to children who were using their amplification for a minimum of 8 hours per day, often during all waking hours, or hearing aid use is assumed to be full-time in the predictive models. Many infants and young children who are hard of hearing wear their hearing aids for a limited number of hours per day depending on their age and degree of hearing loss (Moeller et al. 2009; Walker et al. 2013). A model that assumes full-time hearing aid use might overestimate the risk of further hearing loss due to over-amplification in children who use their hearing aids less than the 8 hours per day that is associated with the ATS. Children with a greater number of hours of hearing aid use per day would be expected to have greater risk for threshold shift than peers with more limited hearing aid use. If increased hearing aid use increases the risk for over-amplification in some children, those risks would need to be balanced with evidence that suggests that greater number of hours of hearing aid use are also associated with improved outcomes in language (Tomblin et al. 2015) and speech recognition (McCreery et al. 2015).

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the prevalence and magnitude of threshold shifts for a large group of children with hearing aids fit using DSL who were followed as part of the longitudinal Outcomes of Children with Hearing Loss study. Behavioral thresholds were measured every 6 months for children ages 2 years and younger and annually for children over the age of 2. Behavioral threshold data in both dB HL and dB SPL were used to estimate the number of children who would exceed safety limits based on the MPL. These estimates of ATS were compared to the magnitude of the actual threshold shifts (if any) that occurred. Hearing aid verification data were also collected at the same visits. Hearing aid use time was estimated from a parent questionnaire about hearing aid use consistency to examine whether differences in hearing aid use moderated risk for progression of hearing loss due to over-amplification. Three research questions were evaluated:

What are the predicted ATS for children who wear hearing aids that are fit using DSL based on dB HL and dB SPL threshold criteria? Children with thresholds in the moderate to severe hearing loss range were expected to have model-predicted asymptotic threshold shifts. Children with higher thresholds and those who were fit above DSL targets were hypothesized to have larger asymptotic threshold shifts based on the MPL model predictions.

What is the relationship between predicted asymptotic threshold shifts and changes in audiometric thresholds in children with hearing aids fit to DSL targets? Children with predicted asymptotic threshold shifts were expected to experience increases in hearing thresholds over consecutive study visits.

How does the proximity of the fitting to prescriptive target or amount of hearing aid use moderate the predictions of asymptotic threshold shift in children with hearing aids? We predict that children with fittings that match prescriptive targets or with more than 8 hours of hearing aid use will be more likely to experience amplification-related shifts in threshold than peers who have hearing aids set below DSL prescription or who wear their hearing aids for fewer than 8 hours per day.

These findings will support evidence-based decisions about hearing aid prescriptions, balancing safety with providing sufficient amplification to maintain consistent audibility.

METHOD

Participants

A subsample of children who wore hearing aids and were followed as part of the longitudinal Outcomes of Children with Hearing Loss study (Moeller & Tomblin, 2015) was selected for inclusion in the current analyses. Two-hundred and ninety-two children with mild to severe permanent hearing loss were considered for inclusion. To be included in the current analyses, children needed to have a minimum of two study visits over at least 12 months where frequency-specific audiometric threshold and measured hearing aid verification data were obtained. Fourteen children with only a single study visit were excluded. Forty-two children were excluded due to the presence of middle ear dysfunction at one or more study visits. Children with known etiologies associated with progressive or fluctuating hearing loss were excluded, including children with confirmed auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (n=9), enlarged vestibular aqueduct (n=12), or history of cytomegalovirus (n=2). Pre-implant data for children who eventually received cochlear implants (n=10) were included if all other study criteria were met. Two hundred and thirteen children met all of the criteria for inclusion and are reported in the analyses that follow.

Audiometric assessment

Audiological assessment was completed in a sound-treated audiometric test booth or mobile test van by an experienced pediatric audiologist. Audiometric thresholds were measured at octave frequencies (250 Hz – 8000 Hz) using developmentally-appropriate behavioral methods, including visual reinforcement audiometry, conditioned play audiometry, or conventional audiometry. Inter-octave frequencies were tested if a difference of 15 dB or greater was observed between octave test frequencies. Bone conduction thresholds were obtained whenever the child’s cooperation permitted. The number of test frequencies obtained at each study visit depended on the child’s attention span and cooperation. Data were obtained for a total of 1,338 audiometric evaluations (2,676 ears) across 213 children. Insert earphones (Etymotic Research, ER-3A) coupled to pediatric foam tips or the child’s personal earmolds were used to assess air conduction thresholds reported in this analysis. The audiologist rated reliability as good, fair or poor. Audiograms with poor reliability (Visit 1=4, Visit 2 = 10, Visit 3 = 4 and Visit 4 = 0) were excluded from the analyses. Tympanometry using a 226 Hz probe tone was assessed at the study visit whenever possible. Normal tympanometry was classified as admittance > 0.2 mmho and tympanometric peak pressure between +100 and −150 daPa. The presence of tympanostomy tubes was determined by a residual ear canal volume greater than 2 cm3 and otoscopic inspection of the ear canal.

Hearing aid verification

Hearing aid verification with probe microphone measures was completed at each visit to measure or estimate the output of the hearing aid in the child’s ear. Individually-measured real-ear-to-coupler difference (RECD) values with the child’s personal earmolds or insert foam tips were used whenever possible. If the child would not cooperate with individually-measured RECD, age-related average RECD values were used to simulate in situ measurements of hearing aid output in the 2 cm3 coupler of the Audioscan Verifit. In situ measurements of output with the hearing aid in the child’s ear were completed with older children when their cooperation permitted. The hearing aid verification data obtained at each study visit was compared to DSL prescriptive targets. The DSL prescription was reported to be used to prescribe amplification for each child in this analysis according to a survey of each child’s dispensing audiologist (McCreery, Bentler & Roush, 2013). The frequency-specific deviation from prescriptive targets at 500 Hz, 1000 Hz, 2000 Hz and 4000 Hz was calculated for each participant. The frequency-specific deviation from target was used instead of previously reported measures of proximity to targets that represent an average across frequency, such as root-mean-square error (McCreery, Bentler & Roush, 2013), due to the need to specify proximity to targets at specific frequencies.

Aided audibility for speech

The aided audibility of speech was calculated using a modification of the Speech Intelligibility Index (SII; ANSI S3.5 – 1997, R2007). The audibility of the long-term average speech spectrum was calculated for each listener, ear and input level, assuming a non-reverberant environment. The 1/3-octave-band calculation method was used with the average band-importance weighting function from Table 3 of the ANSI SII standard. The levels of speech were converted to free-field using the free-field to eardrum transform from the SII. Audiometric thresholds were converted from dB HL to dB SPL and then interpolated and extrapolated to correspond with 1/3-octave-band frequencies using a frequency-specific bandwidth adjustment to convert pure tone thresholds to equivalent 1/3-octave-band levels (Pavlovic, 1987). The band-specific levels of speech and threshold-equivalent noise for each child’s audiogram were entered into a spreadsheet to calculate sensation level (SL) for each 1/3-octave band. The SL in each band was divided by 30 dB. The SL was multiplied by the importance weight for that band, and the sum of these products for all bands generated the SII for each condition. For children with nonlinear frequency compression, the SII calculation was the same as for children with conventional processing, except the SL for each frequency band above the start frequency was calculated at the frequency where the filtered band was measured during the verification process with nonlinear frequency compression activated as in two previous studies (McCreery et al. 2014; Bentler et al. 2014).

Estimation of predicted asymptotic threshold shifts (ATS)

The predicted ATS for children in this study were individually estimated using two different threshold criteria: dB HL and dB SPL. The dB HL criterion was used to compare to previous studies (e.g. Ching et al. 2013a) where risk of threshold shifts was estimated based on the DSL prescribed output of the hearing aid for an 80 dB SPL input using the measured dB HL threshold at 500 Hz, 1000 Hz, 2000 Hz and 4000 Hz. Children were categorized as being above or below the safety limit predicted by the Modified Power Law based on their dB HL threshold and DSL prescribed gain. The dB SPL criterion was based on the measured hearing aid output in dB SPL in the ear canal for an 80 dB SPL speech input and the behavioral threshold converted to dB SPL. The 80 dB input level was selected because of data from Ching et al. (2013a) that suggest that young children are likely to be exposed to sound levels above 80 dB SPL in their everyday listening environments. If the measured 80 dB SPL level was not available for specific child, that value was extrapolated from measured hearing aid output data at lower input levels using linear regression. Verification data in one-third octave bands was converted to octave bands. The prescribed (based on dB HL) or measured (based on dB SPL) outputs of each child’s hearing aids with an 80 dB input at 500 Hz, 1000 Hz, 2000 Hz, and 4000 Hz were converted to intensity and used to generate predicted ATS using Equation 1 (Macrae, 1994):

where Ie is the intensity of an octave band of noise and Ic is the intensity of the critical level for temporary threshold shifts (TTS) reported by Mills (1982; 500 Hz = 84 dB SPL; 1000 Hz = 86 dB SPL; 2000 Hz =89 dB SPL; 4000 Hz = 87 dB SPL). Equation 1 generates an ATS prediction based on an assumption of normal hearing. The predicted threshold shift depends on the degree of hearing loss. Therefore, the frequency-specific ATS for each subject were then applied to the Modified Power Law equation (Humes & Jesteadt, 1991) to estimate the predicted threshold shift as in Equation 2:

where T′ is the predicted threshold in the ear with sensorineural hearing loss after ATS, T is the baseline threshold, ATS is the estimate from Equation 1, and P is a constant equal to 0.2 (Macrae, 1994).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were completed using the R software interface (Version 3.1.1; R Core Team, 2014) and the lme4 (Bates et al. 2014) and ggplot2 (Wickham & Chang, 2014) packages. Linear mixed models were used to relate the dB HL at each frequency across visits to the fixed effects of age in months, a categorical factor for visit (1–4), a categorical factor for risk group (above vs. below the safety limit based on dB HL threshold from Ching et al. 2013a) and an interaction between age and risk group to account for differences in threshold over time between the two risk groups. The interaction between visit and risk category was used to assess whether or not changes in threshold over time were greater for the group above the dB HL risk criterion than the group below the risk criterion. Separate linear mixed models were completed for each frequency due to differences in risk group for the same subjects across frequencies. Each linear mixed model included a term for random intercept for each subject, due to differences in thresholds across subjects, and a term for random slope across time to allow slope to vary for listeners that had changes in threshold over time. A level 2 random intercept for ear was nested within each subject to account for dependence and clustering between left and right ears from the same subject. All predictor variables were mean-centered to minimize the potential for multicollinearity. Model assumptions, including normality, were assessed through residual analysis and there was no evidence of violation of the modeling assumptions. Due to the relatively small number of subjects who fell above the safety limit based on the dB SPL threshold and measured hearing aid output, linear mixed models with multiple predictors could not be used to assess changes in thresholds over time. Therefore, a repeated-measures analysis of variance was used to analyze the mean differences in thresholds between visits for subjects above the dB SPL criterion.

RESULTS

Table 1 includes the demographic information for subjects included in the analyses.

Table 1.

Subject group characteristics at each study visit

| Visit | n | Age | HL conf (months) | HA fit (months) | BEPTA | BESII | HA Use | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | M | Med | SD | M | Med | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| 1 | 213 | 44.1 | 14.1 | 5 | 17.2 | 18 | 8 | 18.4 | 47.3 | 13.4 | 0.77 | 0.14 | 10 | 3.1 |

| 2 | 213 | 51.6 | 13.2 | 4 | 17 | 16.1 | 7 | 18.2 | 49.8 | 13.1 | 0.75 | 0.15 | 10.9 | 3.1 |

| 3 | 179 | 60.4 | 11.5 | 3 | 15.8 | 15.8 | 7 | 17.3 | 49.4 | 14.1 | 0.76 | 0.12 | 10.7 | 3.0 |

| 4 | 116 | 68.3 | 10.7 | 3 | 16.1 | 14.2 | 5 | 17.5 | 49.3 | 14.6 | 0.76 | 0.15 | 11.6 | 2.9 |

Age = age in months ;HL conf = age hearing loss confirmed; HA = hearing aid; BEPTA= better-ear pure tone average in dB HL; BESII = better-ear aided speech intelligibility index;

HA Use = hours per day from parent report

M = mean; Med = median; SD = standard deviation

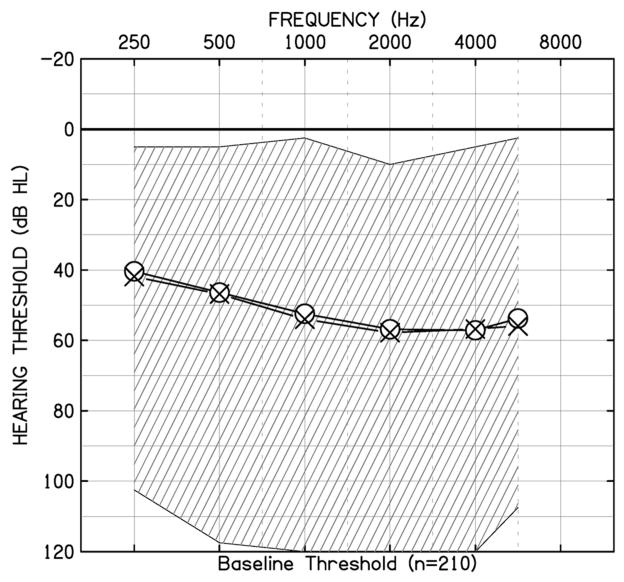

The mean and the range of audiometric thresholds in dB HL as a function of frequency at Visit 1 are plotted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Air-conduction thresholds at the first study visit in dB HL as a function of audiometric test frequency. Circle symbols are the mean thresholds for the right ear, X symbols are the mean thresholds for the left ear. The cross-hatched area represents the range of dB HL thresholds in the sample.

Overall, the sample included children with thresholds in the mild to profound hearing loss range who had aided audibility within the normative range for their degree of hearing loss (Bagatto et al. 2011) and used their hearing aids approximately 10–11 hours per day per parent report. The frequency-specific deviations from DSL targets are presented in Figure 2. The percentage of the children that had hearing aids that were within 5 dB of prescriptive targets was 58% at 500 Hz, 55% at 1000 Hz, 60% at 2000 Hz and 68% at 4000 Hz.

Figure 2.

The deviation from prescriptive target in dB as a function of frequency (Desired Sensation Level (DSL) Target minus REAR). Boxes represent the interquartile range (25th – 75th percentiles of the mean). Whiskers represent the 5th – 95th percentiles. Horizontal lines within each bar represent the median. Filled circles represent individual subjects outside of the 5th–95th percentiles.

Thresholds shifts based on the dB HL safety limit

Children were categorized based on their dB HL thresholds and predicted DSL gain prescriptions for 80 dB HL inputs into being above or below the safety limit estimated from the MPL at each frequency. Table 2 shows the number of children above the dB HL safety limits by visit and by frequency. Changes in thresholds in children who were above the safety limits were compared to children who were below the safety limits using a linear mixed model. Table 3 includes the results for each linear mixed model.

Table 2.

Children above the dB HL safety limit by frequency and visit

| Visit 1 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Visit 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 Hz | 28 (6.6%) | 27 (6.1%) | 30 (8.4%) | 19 (8.2%) |

| 1000 Hz | 43 (10.1%) | 53 (12%) | 46 (12.8%) | 35 (15.1%) |

| 2000 Hz | 50 (11.7%) | 61 (13.9%) | 59 (16.5%) | 38 (16.4%) |

| 4000 Hz | 65 (15.3%) | 66 (15%) | 59 (16.5%) | 30 (12.9%) |

| 1 frequency | 35 (8.2%) | 43 (9.8%) | 35 (9.8%) | 23 (9.9%) |

| 2 frequencies | 28 (6.6%) | 24 (5.5%) | 25 (7%) | 10 (4.3%) |

| 3 frequencies | 17 (4%) | 16 (3.6%) | 19 (5.3%) | 17 (7.3%) |

| 4 frequencies | 11 (2.6%) | 17 (3.9%) | 15 (3.6%) | 7 (3%) |

Number and percentage of the ears above the safety limit from the MPL based on DSL prescription for an 80 dB SPL input.

Table 3.

Linear mixed model for dB HL safety limits by frequency

| Model | Fixed effects | Random effects | ||||

| 500 Hz | Factor | F | Coef (SE) | P | Factor | Variance |

| Age | 1.05 | −0.04 (0.03) | 0.3 | Subject | 256.2 | |

| Risk | 219.5 | 35.6 (2.4) | <0.001 | Ear | 29.3 | |

| Visit | 2.9 | 5.2 (1.2) | 0.03 | Age | 0.05 | |

| Age*Risk | 30.3 | −0.22 (0.05) | <0.001 | Residual | 34.6 | |

| Model | Fixed effects | Random effects | ||||

| 1000 Hz | Factor | F | Coef (SE) | P | Factor | Variance |

| Age | 1.05 | −0.05 (0.04) | 0.16 | Subject | 241.7 | |

| Risk | 112.7 | 22.7 (2.1) | <0.001 | Ear | 50.1 | |

| Visit | 4.1 | 5.5 (1.1) | 0.02 | Age | 0.07 | |

| Age*Risk | 6.2 | −0.09 (0.03) | <0.001 | Residual | 28.6 | |

| Model | Fixed effects | Random effects | ||||

| 2000 Hz | Factor | F | Coef (SE) | P | Factor | Variance |

| Age | 0.28 | −0.01 (0.03) | 0.6 | Subject | 140.1 | |

| Risk | 145.5 | 21.5 (1.8) | <0.001 | Ear | 58.9 | |

| Visit | 9.6 | 8.1 (1.1) | <.0001 | Age | 0.04 | |

| Age*Risk | 6.2 | −0.07 | <0.001 | Residual | 25.3 | |

| Model | Fixed effects | Random effects | ||||

| 4000 Hz | Factor | F | Coef (SE) | P | Factor | Variance |

| Age | 0.02 | −0.05 (0.03) | 0.88 | Subject | 120.8 | |

| Risk | 201.2 | 26.1 (1.8) | <0.001 | Ear | 33.6 | |

| Visit | 9.5 | 8.2 (1.2) | <0.001 | Age | 0.03 | |

| Age*Risk | 4.8 | −0.065 (0.3) | <0.001 | Residual | 33.2 | |

Age = age in months; Risk = Below (0) or Above (1) the dB HL safety limit

Each model has large variance for the random subject intercept due to the large range of thresholds across children included in the analysis. The same pattern was observed for the fixed effects for each frequency. The age by risk group interaction was statistically significant (p < 0.0001), indicating that the thresholds at each frequency for the group above the safety limit differed from the group below the safety limit as age increased. The negative sign for each coefficient indicates that the group above the safety limit at each frequency had lower (better) thresholds across age than the group below the safety limit, which is in the opposite direction of the prediction of the MPL model. However, the coefficients at each frequency are small (range = −0.065 to −0.22), indicating that predicted amount of change in threshold per year is less than 3 dB at each frequencies. The fixed effect of age on threshold was not significant, indicating that thresholds did not vary as a function of age across subjects. The fixed effect for risk group was significant for all four frequencies with higher (poorer) thresholds for children in the group above the safety limit than children below. Thresholds decreased as a function of visit by 1–3 dB depending on the frequency and visit number. The fixed effect for visit corresponds with the small amount of change predicted in the age by risk interaction.

Threshold shifts based on a dB SPL safety limit

For a subsample of children who had hearing aid verification with either in situ probe microphone measures or coupler measures using a measured real-ear-to-coupler difference (n=180), the predicted threshold shifts were estimated based on the dB SPL threshold and measured dB SPL output for an 80 dB input. Table 4 displays the number of children above the safety limit based on the dB SPL criterion by frequency and visit. The numbers and percentages of children above the safety limit based on dB SPL threshold and measured hearing aid output were smaller than the number above the safety limit based on the dB HL criterion. The changes in threshold over time for subjects above the dB SPL risk criterion were compared to the changes observed in the group of children who were below the risk criteria.

Table 4.

Children above the safety limit by frequency and visit based on dB SPL criteria

| Visit 1 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Visit 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 Hz | 2 (1%) | 6 (2.8%) | 6 (2.1%) | 6 (2.8%) |

| 1000 Hz | 1 (0.6%) | 12 (5.6%) | 19 (6.8%) | 7 (3.2%) |

| 2000 Hz | 5 (2.8%) | 21 (13.9%) | 30 (10.7%) | 22 (10%) |

| 4000 Hz | 4 (2.2%) | 2 (1%) | 7 (2.5%) | 1 (0.5%) |

Number and percentage of the ears above the safety limit from the MPL based on dB SPL threshold and 80 dB SPL input.

Figure 3 shows the threshold data for subjects who were above the dB SPL risk criterion at each frequency between visits. A repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted with frequency (500 Hz, 1000 Hz, and 2000 Hz) and visit (1–4) as within-subjects factors. Given the distribution of children above the safety limits across visits, the visits were converted to 0 (visit where child was over safety limit) and 1 (the next study visit). Children without a study visit following the visit where they were above the dB SPL safety visit were not included in the ANOVA. This left only two subjects above the safety limit at 4000 Hz who had the same dB SPL threshold across visits, so 4000 Hz was not included in the ANOVA. There were no significant differences in threshold as a function of frequency [F(2,65)=1.24, p=0.213, η2p=0.014] or visit [F(3,65)=0.024, p=0.818, η2p=0.002]. Children who were over the dB SPL safety limit were fit above DSL targets. The average deviations from prescriptive target for the group of children who were over the safety limit was 3.9 dB at 500 Hz, 4.3 dB at 1000 Hz, 1.5 dB at 2000 Hz, and 6.8 dB at 4000 Hz, which indicates that the children over the dB SPL safety limit tended to have fittings that exceeded DSL prescriptive targets, rather than being less than prescriptive targets like many of the children below the safety limit.

Figure 3.

The dB SPL thresholds plotted as a function of frequency and visit for children above the safety limit based on dB SPL threshold and measured dB SPL hearing aid output. Visit was collapsed into 0 (visit where dB SPL safety limit was exceeded) and 1 (next study visit) due to the small number of subjects above the safety limit at each visit and frequency. Only two subjects were above the safety limit at 4000 Hz, both with the same dB SPL threshold at both visits. Boxes represent the interquartile range (25th – 75th percentiles of the mean). Whiskers represent the 5th – 95th percentiles. Horizontal lines within each bar represent the median. Filled circles represent individual subjects outside of the 5th–95th percentiles.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to evaluate changes in audiometric threshold for a group of children, some of whom who were classified as being above amplification safety limits proposed in previous research by Macrae (1993, 1994) and Ching et al. (2013a). Two different estimates of the safety limit were compared: one based on each child’s dB HL threshold and predicted output for DSL for an 80 dB input as in Ching et al. (2013a) and one based on the child’s dB SPL threshold and measured hearing aid output for an 80 dB input. The 80 dB SPL input was selected because of evidence from Ching et al. (2013a) that young children are likely to encounter listening environments with intensity levels above this level, which could put them at risk for amplification-induced progression of hearing loss. Children above the safety limits were predicted to have poorer thresholds over the course of the study than children below the safety limits. The dB SPL safety limits were expected to produce more accurate estimates of risk for amplification-induced hearing loss because they take into account individual differences in ear canal acoustics and hearing aid output. This is the same rationale that supports recommendations for routine real-ear verification of children’s hearing aids (AAA, 2013; Bagatto et al., this issue). Children above the safety limit who had more limited hearing aid use were predicted to have preservation of hearing compared to children above the safety limit who had more hours of hearing aid use by parent report. The dB SPL threshold criterion predicted a smaller percentage of children above the safety limit than the dB HL threshold criterion. Changes in threshold over the course of the study were observed with approximately a 1–2 dB increase in threshold at each visit as children increased in age. However, changes in threshold were observed regardless of whether or not children were above the safety limit for amplification predicted by the MPL. These results raise questions about the utility of the MPL for predicting risk of amplification-induced hearing loss in children who use nonlinear amplification.

Behavioral thresholds for children who wear hearing aids were stable with small changes in threshold observed across study visits that spanned 2–4 years of time in the study. The 1–2 dB increase in thresholds between visits could be associated at least partially with changes in ear canal acoustics that are observed as children’s ear canals grow. Increased ear canal volume lowers the dB SPL level in the child’s ear canal. As a result, dB HL thresholds may appear to become poorer over time if differences in ear canal volume are not taken into account. These results should not be taken as evidence for the stability of hearing during early childhood, as children with changes in middle ear status due to middle ear dysfunction and etiologies of hearing loss known to be associated with progressive or fluctuating hearing loss were excluded from this analysis. Nonetheless, these results suggest that children with mild to profound sensorineural hearing loss do not appear to be at-risk from further damage to their hearing from appropriately-fit amplification using the DSL prescriptive approach.

These results may appear to contradict previous studies, which observed changes in thresholds for children fit with linear amplification (Macrae, 1993; 1994; 1995) and predicted that some children with severe hearing loss might be at-risk for amplification-induced hearing loss due to the amount of prescribed amplification for high-input levels for the DSL prescription (Ching et al. 2013a). The temporary and permanent threshold shifts reported by Macrae were for children using linear amplification that was 20–30 dB above recommended limits for periods up to 8 years. Findings from Macrae’s studies helped to support many current hearing aid verification recommendations and guidelines for children, including the use of probe microphone measurements of the hearing aid output in the child’s ear canal or simulated measurements of the hearing aid output in a coupler with a real-ear-to-coupler-difference measure (AAA, 2013; Bagatto et al. 2010; King, 2010; Bagatto et al. this issue). Probe microphone verification can minimize the likelihood of over-amplification of the magnitude that was observed in the studies by Macrae. Nonlinear amplification that is primarily used today is likely to have lower outputs at high input levels than the linear amplification used by the children in the study by Macrae, which could also have limited the risk of amplification-induced threshold shifts observed in this cohort of children. Additional protection may be available through the use of noise management or other level-reduction strategies in high-noise environments (Scollie, this issue). The protective effects of noise management signal processing strategies have not been evaluated directly.

Predictions of threshold shift based on nonlinear prescriptions were reported by Ching et al. (2013a). Safety limits reported by Ching et al. were based on the child’s dB HL thresholds and frequency-specific predictions of hearing aid output based on two different nonlinear prescriptions: NAL-NL2 and DSL. Predictions for the DSL prescriptive formula suggested that children with thresholds above 70 dB HL would likely be at-risk for exceeding the safety limit. Between 5–16% (depending on the frequency) of children in the current study were above a safety limit based on their dB HL thresholds. However, differences between the group above and the group below the safety limits were small (less than 3 dB/visit) and in the opposite direction of predictions of increasing risk for progression of hearing loss due to over-amplification, as the group below the safety limits had poorer hearing thresholds over time at each of the four test frequencies than the group of children above the safety limit.

However, safety limits based on the dB HL threshold and predictions of hearing aid output do not take into account individual differences in ear canal acoustics nor in the actual hearing aid output in the child’s ear canal. The effects of these factors were examined by generating frequency-specific safety limits for each child in the study using the dB SPL thresholds and hearing aid outputs for an 80 dB SPL input. The dB SPL safety limits identified a smaller number of children (0.6–13%) as being at-risk for amplification-induced hearing loss than the safety limits based on dB HL. Children above the safety limits for the dB SPL criterion had hearing aid outputs above the recommended prescriptive targets, which means they may not have been identified as being at risk based on the dB HL safety limits. Nonetheless, significant changes in threshold were not observed at any frequency between visits where children exceeded the safety limits for their dB SPL thresholds and hearing aid outputs. The dB SPL safety limit identified fewer children as being at risk for over-amplification than the dB HL safety limit. However, these differences between the dB HL and dB SPL safety limits appear to be of limited consequence since threshold shifts were not observed in children above the safety limits for either approach.

Hearing aid use was predicted to moderate the potential for progression of hearing loss due to over-amplification. Specifically, children above the safety limit with hearing aid use less than 8 hours per day were expected to have smaller changes in threshold than children above the safety limits with more than 8 hours of hearing aid use per day. Given that the changes in threshold over time were small and occurred for children regardless of their risk category, the moderation of risk could not be evaluated in the current study. Children in the study wore their hearing aids for over 10 hours / day on average, which would be sufficient to achieve the asymptotic threshold shift described by Mills (1982). Limiting the number of hours of hearing aid use to avoid changes in thresholds would not be supported by these findings. Children who wear their hearing aids for a greater number of hours per day are likely to have better language development (Tomblin et al. 2015) and speech recognition abilities (McCreery et al. 2015) than children with fewer hours of hearing aid use. Therefore, monitoring and supporting hearing aid use during early childhood can support optimal developmental outcomes.

These results have several implications for audiologists who fit children with hearing aids. First, the risk of amplification-induced hearing loss for children with mild to severe hearing loss who are fit according to the AAA Pediatric Amplification Guidelines appears to be minimal. Children who were at the greatest risk due to higher thresholds, higher hearing aid outputs or fittings that exceeded prescriptive recommendations did not experience deterioration of hearing, as was predicted by safety limits based on the Modified Power Law. The recommendation to limit amplification or audibility to levels less than prescribed by DSL are not supported by the current findings. These results support the need for hearing aid verification using probe microphone measures to ensure that the hearing aids match and do not exceed prescribed levels. The application of safety limits for amplification beyond matching prescriptive targets would not seem to reduce the risk of further damage to hearing loss, because the risk for children above those safety limits appears to be minimal.

Limitations and future directions

Despite the findings that children above the safety limits for over-amplification did not experience threshold shifts that were greater than children below the safety limits for amplification, future research should help to address limitations of the current study. Due to limitations in behavioral audiometric assessment with infants and young children, audiometric data often were only collected at octave band frequencies. Mills (et al. (1979) suggests that the maximum threshold shift is likely to occur at half an octave above the octave band frequency. The current study may have underestimated risk by only measuring thresholds at octave bands, and future studies may collect thresholds at additional frequencies to increase sensitivity. However, the threshold shifts observed from over-amplification in studies by Macrae (1993, 1994, 1995) were not limited to inter-octave frequencies, suggesting that measurement of inter-octave frequencies may not be necessary, particularly for over-amplification of broadband signals through hearing aids. Though the safety limits and critical values are expressed at octave band frequencies, broadband over-amplification is likely to result in widespread cochlear damage that would manifest at multiple frequencies. Further research could be used to confirm this assumption.

Conclusions

Children who wore hearing aids fit to the DSL prescriptive targets were assessed for changes in thresholds based on two different safety limits: one based on the child’s dB HL threshold and predicted hearing aid output for a high-level input and one based on the child’s dB SPL threshold and measured hearing aid output. In both cases, children above the safety limit did not experience changes in threshold that were greater than children below the safety limit. The use of prescriptive targets and hearing aid verification appear to provide adequate protection from amplification-induced hearing loss in children with mild to severe hearing loss.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health – National Institute for Deafness and Communication Disorders (R01 DC013591; R01 DC009560; P20 GM109023, P30 DC004662). The authors wish to thank Earl Johnson for assistance with safety limit calculations. The authors also wish to thank Marlene Bagatto and Susan Scollie for comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AAA

American Academy of Audiology

- DSL

Desired Sensation Level

- MPL

Modified Power Law

- TTS

Temporary Threshold Shift

- ATS

Asymptotic Threshold Shift

- PTS

Permanent Threshold Shift

- OCHL

Outcomes of Children with Hearing Loss

- NAL

National Acoustics Laboratories

- HL

Hearing Level

- SPL

Sound Pressure Level

- RECD

Real-Ear-to-Coupler Difference

- ANSI

American National Standards Institute

- ANOVA

Analysis of Variance

Footnotes

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- American Academy of Audiology. Clinical practice guidelines: Pediatric amplification. Reston, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bagatto MP, Scollie SD, Seewald RC, Moodie KS, Hoover BM. Real-ear-to-coupler difference predictions as a function of age for two coupling procedures. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 2002;13(8):407–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagatto M, Moodie S, Scollie S, Seewald R, Moodie S, Pumford J, Liu KR. Clinical protocols for hearing instrument fitting in the Desired Sensation Level method. Trends in amplification. 2005;9(4):199–26. doi: 10.1177/108471380500900404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagatto M, Scollie SD, Hyde M, Seewald R. Protocol for the provision of amplification within the Ontario Infant Hearing Program. International Journal of Audiology. 2010;49(S1):S70–S79. doi: 10.3109/14992020903080751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagatto MP, Moodie ST, Malandrino AC, Richert FM, Clench DA, Scollie SD. The University of Western Ontario pediatric audiological monitoring protocol (UWO PedAMP) Trends in amplification. 2011;15(1):57–76. doi: 10.1177/1084713811420304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagatto M, Moodie ST, Brown L, Malandrino AC, Richert FM, Clench DA, Scollie SD. Prescribing and Verifying Hearing Aids applying the AAA Pediatric Amplification Guideline: Protocols and Outcomes from the Ontario Infant Hearing Program Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.15051. (in review) this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S, Christensen RHB, Singman H, Dai B. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. 2014 [Computer software] Published 7-19-2014. Available for download at http://cran.r-project.org/

- Ching TY, Johnson EE, Seeto M, Macrae JH. Hearing-aid safety: A comparison of estimated threshold shifts for gains recommended by NAL-NL2 and DSL m [i/o] prescriptions for children. International journal of audiology. 2013a;52(S2):S39–S45. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2013.847976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ching TY, Dillon H, Hou S, Zhang V, Day J, Crowe K, Thomson J. A randomized controlled comparison of NAL and DSL prescriptions for young children: Hearing-aid characteristics and performance outcomes at three years of age. International Journal of Audiology. 2013;52(S2):S17–S28. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2012.705903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson LS, Skinner MW. Audibility and speech perception of children using wide dynamic range compression hearing aids. American Journal of Audiology. 2006;15(2):141–153. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2006/018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humes LE, Jesteadt W. Modeling the interactions between noise exposure and other variables. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1991;90(1):182–188. doi: 10.1121/1.401286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keidser G, Dillon HR, Flax M, Ching T, Brewer S. The NAL-NL2 prescription procedure. Audiology Research. 2011;1(1):24. doi: 10.4081/audiores.2011.e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AM. The national protocol for paediatric amplification in Australia. International Journal of Audiology. 2010;49(S1):S64–S69. doi: 10.3109/14992020903329422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrae JH. Permanent threshold shift associated with overamplification by hearing aids. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1991;34(2):403–414. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3402.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrae JH. Temporary threshold shift caused by hearing aid use. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1993;36(2):365–372. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3602.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrae JH. Prediction of asymptotic threshold shift caused by hearing aid use. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1994;37(6):1450–1458. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3706.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrae JH. Temporary and permanent threshold shift caused by hearing aid use. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1995;38(4):949–959. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3804.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreery RW, Venediktov RA, Coleman JJ, Leech HM. An evidence-based systematic review of amplitude compression in hearing aids for school-age children with hearing loss. American Journal of Audiology. 2012;21(2):269–294. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2012/12-0013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreery RW, Bentler RA, Roush PA. The characteristics of hearing aid fittings in infants and children. Ear and Hearing. 2013;34(6):701. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31828f1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreery RW, Alexander J, Brennan MA, Hoover B, Kopun J, Stelmachowicz PG. The Influence of Audibility on Speech Recognition With Nonlinear Frequency Compression for Children and Adults With Hearing Loss. Ear and hearing. 2014;35(4):440–447. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreery RW, Walker EA, Spratford M, Olseon JJ, Bentler RA, Holte L, Roush PA. Speech recognition and parent-ratings from auditory development questionnaires in children who are hard of hearing. Ear and Hearing. 2015 doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000213. ePub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills JH, Gilbert RM, Adkins WY. Temporary threshold shifts in humans exposed to octave bands of noise for 16 to 24 hours. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1979;65(5):1238–1248. doi: 10.1121/1.382791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills JH. Effects of noise on auditory sensitivity, psychophysical tuning curves, and suppression. In: Hamernik RP, Henderson D, Salvi R, editors. New Perspectives in Noise-induced Hearing Loss. Raven Press; New York: 1982. pp. 249–263. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller MP, Hoover B, Peterson B, et al. Consistency of hearing aid use in infants with early-identified hearing loss. American Journal of Audiology. 2009;18:14–23. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2008/08-0010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller MP, Tomblin JB. An Introduction to the Outcomes of Children with Hearing Loss Study. Ear and Hearing. 2015 doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000210. ePub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovic CV. Derivation of primary parameters and procedures for use in speech intelligibility predictions. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1987;82(2):413–422. doi: 10.1121/1.395442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Development Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Computer software] 2014 Available from www.R-project.org.

- Scollie S, Seewald R, Cornelisse L, Moodie S, Bagatto M, Laurnagaray D, Pumford J. The desired sensation level multistage input/output algorithm. Trends in Amplification. 2005;9(4):159–197. doi: 10.1177/108471380500900403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scollie SD. Children’s speech recognition scores: The Speech Intelligibility Index and proficiency factors for age and hearing level. Ear and Hearing. 2008;29(4):543–556. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181734a02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scollie SD. Fitting Noise Management Signal Processing applying the AAA Pediatric Amplification Guideline: Updates and Protocols. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.15060. (in review) this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss S, van Dijk C. Hearing instrument fittings of pre-school children: Do we meet the prescription goals? International Journal of Audiology. 2008;47(sup1):S62–S71. doi: 10.1080/14992020802300904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomblin JB, Oleson JJ, Ambrose SE, Walker E, Moeller MP. The influence of hearing aids on the speech and language development of children with hearing loss. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 2014;140(5):403–409. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomblin JB, Harrison M, Ambrose S, Oleson JJ, Walker EA, Moeller MP. Language Outcomes in Young children with Mild to Severe Hearing Loss. Ear and Hearing. 2015 doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000219. ePub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EA, Spratford M, Moeller MP, Oleson J, Ou H, Roush PA, Jacobs S. Predictors of hearing aid use in children with hearing loss. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2013;44 (1):73. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2012/12-0005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H, Chang W. ggplot2: An implementation of the Grammar of Graphics. 2014 [Computer software] Published 5-21-2014. Available for download at http://cran.r-project.org/