Abstract

Chronic illness stigma is a global public health issue. Most widely studied in HIV/AIDS and mental illness, stigmatization of patients living with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), chronic autoimmune conditions affecting the digestive tract, has garnered increasing attention in recent years. In this paper, we systematically review the scientific literature on stigma as it relates to IBD across its three domains: perception, internalization, and discrimination experiences. We aim to document the current state of research, identify gaps in our knowledge, recognize unique challenges that IBD patients may face as they relate to stigmatization, and offer suggestions for future research directions. Based on the current review, patients living with IBD may encounter stigmatization and this may, in turn, impact several patient outcomes including quality of life, psychological functioning, and treatment adherence. Significant gaps exist related to the understanding of IBD stigma, providing opportunity for future studies to address this important public health issue.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, stigma, discrimination, systematic review

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), which include Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are chronic immune-mediated, inflammatory diseases of the digestive tract characterized by abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and fatigue.1 In some cases, extraintestinal symptoms such as eye or skin inflammation and joint pain are present.2 Perianal fistulas occur in ~30% of IBD patients and may be a considerable source of distress.3 Incidence and prevalence rates of IBD are increasing globally.4 Treatment options for IBD include oral and injectable medications and intravenous infusions, often used in combination to induce remission as defined by symptoms, endoscopic appearance, and biomarkers.1 Surgical interventions are common, with the cumulative risk for surgery 7 years after diagnosis being 29% for CD and 13% for UC.5,6

The physical, psychological, social, and financial ramifications of IBD are substantial, and the understanding of the role of illness stigma in these effects is minimal. Psychosocial functioning including reduced health-related quality of life,7–10 increased depression and anxiety,11–16 and relational17,18 and social issues19 are common. These impacts can be due to the illness itself or side effects from some IBD medications (eg, corticosteroids) or surgery.20,21 Social withdrawals,22 feelings of being different from others,23–25 and degradations in body image23,26 have all been reported. Psychosocial impacts of IBD result in poorer patient reported outcomes including increased health care utilization,27,28 reduced treatment adherence,29,30 and increased disease activity.31–33

Financially, people living with IBD pay ~3,000 to 6,000 USD more annually for health care costs than those without IBD.34 Aggregate annual estimates of total direct health care costs for IBD range from 500 million USD (UC) to 2.3 billion USD (CD).35 Indirect costs from lost productivity and similar issues related to IBD are also in billions of dollars.35–37 Poor IBD self-management contributes to increased financial burdens, and improving illness self-management via improvements in IBD-related self-efficacy, streamlining communication between physician and patient, and increasing patient buy-in to treatments all demonstrate improvement in patient outcomes.38–41 While stigma has not been directly studied in relation to IBD self-management, it is associated with decreases in self-esteem and self-efficacy42 suggesting that stigma may be associated with poorer disease management.

Chronic illness stigmatization, most notably characterized in mental health43–45 and HIV/AIDS46–48 research, is a common and global social issue.49 While the majority of research in this area is in the aforementioned conditions, other chronic illnesses such as cancers,50–52 hepatitis C,53–55 epilepsy,56–58 leprosy,59–61 and obesity62–65 have well-documented stigmatization. Illness stigma has a myriad of public health implications including limiting access to medical care, increasing treatment nonadherence, increased psychological distress, decreased self-esteem and self-efficacy, and increased illness symptoms.66–73 The construct of stigma has evolved since Erving Goffman’s seminal work defining stigma as a state of “spoiled identity” brought on being “deeply discredited” and socially rejected for having a particular trait.74 In 2001, Link and Phelan75 expanded the stigma model to include a convergence of labeling, prevailing cultural beliefs, disconnection of the stigmatized from others, and loss of social status combined with discrimination experiences. Research into stigma remains steady, with several hundred studies being published per year over the past decade.

Prevailing stigma theory delineates stigma into three domains: perceived or felt stigma, where the individuals sense that others hold negative attitudes or beliefs toward them or their condition; enacted stigma, or actual discriminatory experiences; internalized or self-stigma, or belief by the stigmatized individuals that negative attitudes or stereotypes about their condition are true and apply to them.76 A fourth and adaptive domain, stigma resistance, has been captured via research utilizing the Internalized Stigma Scale for Mental Illness by Boyd et al.77 In any particular individual, one to all four of these stigma domains may be at play, and the relationships between each and patient outcomes are well documented.49,70,78–81

Jones et al82 identified six traits of a condition or trait that lend it to stigmatization: concealability, variability in course, aesthetic qualities, disruptiveness, origin, and perceived threat. Of these, the severity of the illness and a perception that the condition was caused by behavior of its bearer are most likely to predict stigmatization.83 Based on these parameters, combined with the social taboo related to bowel symptoms in most cultures, IBD is susceptible to illness-related stigma. The severity of IBD varies by patient, but as a whole IBD is considered a serious illness with complex medical regimens to keep inflammation and symptoms in a state of remission, including the use of intravenous infusions (eg, infliximab and vedolizumab). While the etiology of IBD is better understood today as an immune-mediated disease, historically IBD was viewed as a psychosomatic illness with personality traits that made an individual susceptible to its occurrence. The notion that a person could develop CD due to “obsessional behavior” lends it to stigmatization.84 Today, multiple triggers of disease onset and/or activity are identified including infection, antibiotic use, smoking, low mood, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, and stress.85 Perceived stress, negative mood, and stressful life events are often associated with IBD flares.85 Identifying psychological reasons for disease activity is important, yet brings with it the potential for others to view IBD symptoms as under the person’s control due to a lack of ability to manage his or her psychological state or stress levels.

Initial inquiries into stigmatization of gastrointestinal illness occurred with the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Stigma studies in IBS find that a significant percentage of patients report some illness stigmatization.86 However, differences in the etiology between IBS and IBD (ie, functional vs organic) lend themselves to potential differences in stigmatization.87 Some patients with IBD are also diagnosed with IBS when their CD or UC is considered to be in remission via physiological markers yet the patient continues to exhibit symptoms.88 Unfortunately, to date, no studies exist evaluating stigma experiences in IBD patients diagnosed with IBS. To date, no current reviews of illness stigmatization exist for IBD. In this review, we evaluate the three primary stigma domains and the relationship of each to patient outcomes, disease management, and course.

Systematic review

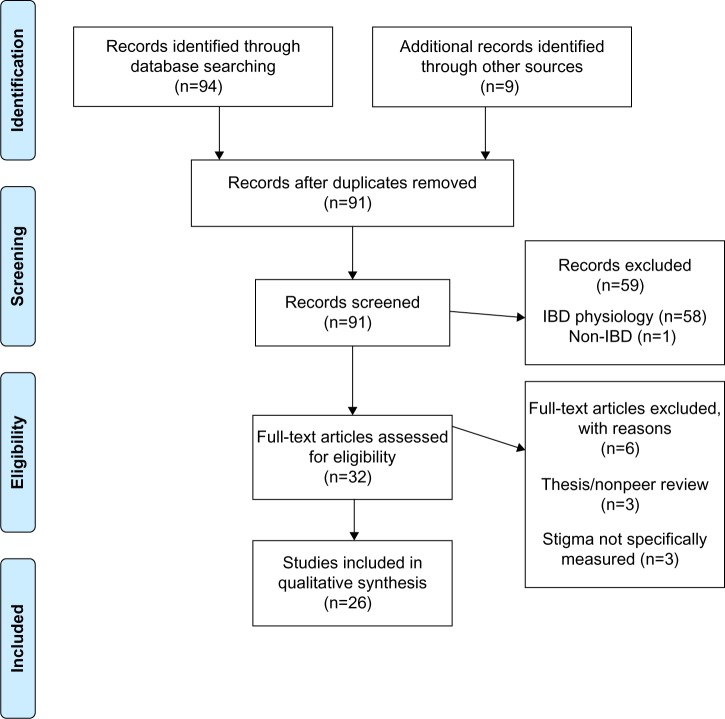

A literature search of studies published in English between 1985 and July 2015 was performed via the online databases PubMed, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar. The 1985 cutoff was selected based on the seminal Jones et al study which better defines stigma as it relates to chronic medical illness.82 The following keyword combinations were used: 1) inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s Disease, ulcerative colitis combined using the “AND” operator with 2) stigma, stigmatized, stigmatization, discrimination, prejudice, stereotype, shame, bullying, blame, and teasing (eg, “Crohn’s disease” AND “stigmatization”). Article titles and abstracts were screened for relevance and full-text articles retrieved for a more detailed review. Reference lists of identified articles and book chapters were also reviewed for additional studies. Unpublished manuscripts and dissertations are not included. Articles identified via the database searches were reviewed by the authors for relevance to the stigma construct and those not specifically addressing stigma were removed from the final review. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram for the literature search is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for systematic review of stigmatization in inflammatory bowel diseases.

Abbreviations: IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Identified studies

Twenty-six studies are reviewed. The majority was published in the USA and evaluate perceived stigma (15 studies). Four studies evaluate internalized stigma, five evaluate enacted stigma, and two evaluate more than one stigma domain. Adult and child/adolescent studies of stigma were included. Specific measures of health-related stigma are abundant and summarized elsewhere.89 The findings are organized by the three stigma domains (Table 1).

Table 1.

Relevant studies of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) stigmatization

| Authors | Study description | No of subjects | Stigma measured | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bernhofer et al92 | Qualitative interview of pain experiences during hospital stay | 16 | Perceived | Labeled as difficult, needy, drug-seeking, unable to tolerate pain properly |

| Czuber-Dochan et al94 | Qualitative interview health care professionals perceptions of IBD-related fatigue | 20 | Enacted | Frustration and poor understanding of IBD-related fatigue |

| Dibley and Norton90 | Mixed qualitative interview, cross-sectional survey of experiences with fecal incontinence | 611 | Perceived | Concerns about how others view IBD, increased social withdrawal/isolation to protect from potential shame |

| Frohlich99 | Qualitative interview of coping with IBD-related stigma | 17 | Perceived | Feelings of guilt from being a burden, feeling of relief after disclosure to safe others |

| Saunders98 | Qualitative interview of stigma experiences | 4 | Perceived | Nondisclosure due to embarrassment from symptoms, challenges related to passing as normal |

| Czuber-Dochan et al93 | Qualitative interview of fatigue experiences | 46 | Perceived | Health care providers have little understanding of IBD-related fatigue |

| Danielsen et al110 | Qualitative interview of impact of ostomy on quality of life | 15 | Internalized | Positive experiences with ostomy, feeling in control of disease management |

| Taft et al113 | Cross-sectional survey of internalized stigma/stigma resistance | 191 | Internalized | 33% report internalized stigma, alienation, and social withdrawal most common; the majority engage in stigma resistance behaviors |

| Taft et al87 | Cross-sectional survey comparing perceived stigma in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and IBD | 496 | Perceived | IBS patients report greater stigma than IBD, larger impact on patient outcomes for stigmatized IBD patients |

| Taft et al42 | Cross-sectional survey measuring perceived stigma | 211 | Perceived | 84% report some perceived stigma. Stigma increases psychological distress, decreases quality of life |

| Voth and Sirois109 | Cross-sectional survey of self-blame and adjustment | 259 | Internalized | Self-blame about IBD correlates with poorer outcomes |

| Smith et al111 | Cross-sectional survey of stigma of ostomy | 195 | Internalized | Ostomy contributes to feelings of shame, self-stigma |

| Finlay et al101 | Cross-sectional survey of racial minority experiences | 148 | Perceived | Caucasians are more likely to disclose IBD status than African-Americans |

| Looper and Kirmayer105 | Cross-sectional survey of felt stigma in functional vs organic illnesses | 89 | Perceived | Perceived stigma is significantly correlated with poorer psychological functioning; no difference in stigma perception between IBS and IBD |

| Krause91 | Qualitative interview of social representations of IBD | 19 | Internalized | Many patients report feelings of shame related to their IBD diagnosis and symptoms |

| Daniel26 | Qualitative interview of young adult experiences | 5 | Perceived, enacted, internalized | Feel others think they use IBD for secondary gain, poor body image/damaged, feel different, feel discredited, shame, concerns about disclosure |

| de Rooy et al95 | Cross-sectional survey of IBD patient concerns | 241 | Perceived | Older patients, women, patients with ulcerative colitis, lower educational level report greater stigma |

| Levenstein et al25 | Cross-sectional survey of IBD patient concerns | 2,002 | Perceived, internalized | Body stigma, feeling dirty, concerns of being a burden reported in patients living in multiple countries |

| Moskovitz et al106 | Cross-sectional survey of social support and surgical outcomes | 86 | Perceived | Poor social support is correlated with worse surgical outcomes |

| Mayberry115 | Cross-sectional survey of personnel managers and workplace discrimination | 195 | Enacted | 30% would not provide leave for outpatient care. IBD impacts promotion decisions in 8% of managers. 60% would make accommodations |

| Moody et al104 | Cross-sectional survey of social implications of childhood IBD | 64 | Perceived | 50% of students report teachers unsympathetic toward IBD |

| Mayberry et al102 | Cross-sectional survey of workplace/education discrimination | 116 | Enacted | 50% of patients with Crohn’s disease had trouble finding work compared to 24% of controls |

| Moody et al100 | Cross-sectional survey of employer attitudes toward IBD | 53 | Enacted | 25% of employers would not continue to employ people if they developed IBD, 30% would not provide time off work to attend appointments |

| Drossman et al23 | Questionnaire validation of IBD patient concerns | 991 | Perceived | Body image, concerns about being a burden, feeling dirty or smelly common concerns |

| Salter108 | Qualitative interview of stigma of ostomy | 7 | Internalized | Ostomy increases self-stigma, shame, body image issues |

| Wyke et al103 | Cross-sectional survey of workplace discrimination | 170 | Perceived, enacted | 81% disclosed IBD, 80% coworkers, 77% employers generally helpful about IBD |

Perceived or felt stigma

The most widely studied of the stigma domains in IBD is perceived or felt stigma, with 84% of participants in a recent study reporting some perceived stigma.42 Several studies report persons living with IBD having concerns about how others see them,25,26,90 feeling different than others,26 feeling shame,91 and feeling discredited, including by medical providers.26,87 For example, hospitalized patients requiring pain management report being labeled as a difficult patient, needy, that they cannot tolerate pain properly, or are inappropriately seeking narcotic painkillers (ie, drug-seeking patients).92 Fatigue is a commonly reported IBD symptom and patients report significant social impact with little understanding from their medical providers.93 A follow-up inquiry by the same author with health care providers found that considerable frustration and difficulty in understanding IBD-related fatigue was common,94 indicating a significant disconnect between providers and patients. Older patients, especially women and patients with UC, tend to report greater disease felt stigma as do patients with lower educational backgrounds.95,96 Stigma perceptions appear to be stable whether the disease is active or in remission and do not appear to vary between UC and CD.23

As IBD is a concealable illness, the issue of disclosure is a salient concern for many patients. Individuals living with concealable conditions may opt to “pass” as someone without a chronic illness or “cover” by downplaying the severity of its symptoms.97,98 Most often, persons living with IBD report nondisclosure due to embarrassment related to its symptoms.98 Fears of the threat of incontinence, bowel sounds, or urgency while in public can have significant negative impacts on patients’ social interactions, often leading to withdrawal and isolation as to protect themselves from potential shame.26,90 Passing can be challenging, especially when the patient must use the toilet multiple times per day,98 so covering is more often employed especially to “safe others”. Guilt about being a burden to others and stoicism may also contribute to nondisclosure.26,99 Concealment is often associated with reduced communication, interactions, and transactions with others thereby increasing feelings of isolation and depression. Disclosure can yield positive results, providing a sense of relief from the stress of keeping IBD hidden and mitigating the effects of stigma.99

As can be expected, experiences with IBD disclosure vary considerably. Some patients report being very open about their condition while others may tend to keep it hidden except with family and close friends.99 Disclosure in employment settings comes with its own unique challenges.100 Racial differences exist, with Caucasians more likely than African-Americans to disclose their IBD status to their employer or fellow employees.101 The reactions in occupational settings are mixed. A 1992 study of patients with CD found that 37% of patients currently employed felt their employer did not need to know about their IBD and 30% were in favor of active concealment. Additionally, 24% felt IBD had limited their employment prospects including avoiding seeking a promotion or being denied promotion because of their illness.102 Conversely, a 1988 study found the majority of participants reported high workplace disclosure (81%), and that 80% of coworkers and 77% of employers had been generally helpful.103 These significantly different findings on employer attitudes may be related to a wide variability in employment culture as a whole, geographic differences in health-related stigma, or the level of familiarity that surveyed employers had with IBD. It highlights that IBD patient experiences with perceptions of negative attitudes from employers will likely vary widely, highlighting the importance of inquiring about each individual’s experience in a clinical setting. Academic and school settings also present challenges for people living with IBD. In one study, 50% of children reported that their teachers were unsympathetic toward their illness.104 Another study found that 21% of college-aged students found lecturers to be indifferent and 8% found them to be hostile toward their disease.102

Perceived stigma in IBD patients is associated with several outcomes including increases in psychological distress,42,105 decreases in health-related quality of life, reduced medication adherence, and decreased self-esteem and self-efficacy.42 Patients who perceive poor social support prior to surgery report poorer quality of life after the procedure.106 If the surgical intervention results in an ostomy, quality of life may improve in some patients in that they feel more in control of their illness107 while others may experience an increase in both perceived and internalized stigma.108 Simply perceiving that others hold these negative attitudes is sufficient to degrade patient well-being. Whether or not the individual internalizes the stigma can lead to even greater distress, and thus, is an important line of inquiry in stigma research.

Internalized or self-stigma and stigma resistance

Internalized or self-stigma may be related to the poorest outcomes of the three stigma domains in that patients apply negative attitudes and stereotypes to themselves rather than rejecting them as false. Internalized stigma includes alienation, stereotype endorsement, discrimination experiences, and social withdrawal.77 Patients with IBD report feeling damaged,26 especially as it relates to physical changes from the disease or its treatments (eg, weight loss or gain, stunted growth, and skin rashes). Self-blame regarding the onset of IBD or the presence of its symptoms postdiagnosis is associated with poorer adjustment to the illness.109 The presence of an ostomy can contribute to self-stigma in some cases,110,111 while in others it produces positive results including feelings of satisfaction with their illness management.112

One study specifically evaluates internalized stigma and stigma resistance in IBD.113 Overall, 33% of people living with IBD report internalized stigma with alienation and social withdrawal being the most common. In general, IBD patients report mild levels of internalized stigma while a larger majority report stigma resistance attitudes and behaviors suggesting that while IBD patients perceive others hold stigmatizing views, they tend to not incorporate them into their sense of self. Levels of internalized stigma are associated with lower educational levels, residing in an urban setting, and having extraintestinal symptoms. Unlike stigma perception, patients who identified themselves as in remission reported less internalized stigma and greater use of stigma resistance behaviors. Internalized stigma in IBD patients predicts reduced health-related quality of life, poorer self-esteem and self-efficacy, and increased psychological distress. These findings are similar to internalized stigma studies in other patient populations.53,70,114

Enacted stigma

Studies on enacted stigma in IBD are limited. Patients report many people simply do not understand IBD, which may cause some to accuse persons with IBD of exaggerating their condition for secondary gain.26 In 1992, Mayberry found that 50% of CD patients compared to 24% of matched healthy controls had significant trouble finding work and long-term unemployment exceeding 6 weeks.102 Mayberry115 evaluated employer attitudes and practices toward people living with CD. Only two out of 35 companies would reject candidates because of IBD. However, 33 of 35 would rely on preemployment medical examinations to make hiring decisions and 8% said IBD would negatively impact promotion consideration. Sixty percent would support employee experiencing a relapse by providing a lighter work period and 16% would pay for private care; 30% would not extend paid leave time for outpatient appointments. Due to the dearth of studies on enacted stigma in IBD patients, additional research is important to close the gaps in the understanding of how common enacted stigma is, what the more common sources of discrimination are, and how enacted stigma influences outcomes.

Discussion

Based on the results of this review, IBD is susceptible to stigma because of its concealability, embarrassing symptoms, and historical view of IBD being a psychosomatic condition. The most commonly studied type of stigma is perceived stigma, evident in 17 studies and demonstrating that the majority of IBD patients perceive stigma from their peers, significant others, colleagues, and physicians.42 Perceived stigma is the easiest construct to identify, but may have less to do with outcomes than “deeper” levels of stigma such as internalized or enacted. For example, patients who perceive stigma but do not internalize it may utilize coping strategies that would be found in any stigma-reducing intervention technique (eg, cognitive reframing). Future research could probably shift away from perceived stigma at this point and focus on other forms.

Internalized stigma, or the incorporation of stigmatizing beliefs and attitudes into one’s sense of self, is potentially the most detrimental to IBD outcomes because it results in declines across physical and psychological functioning more than perceived stigma. In other disease groups, similar findings are noted.77 As IBD requires substantial self-management to maintain remission, adhere to medications, follow disease surveillance protocols (eg, colonoscopy and regular laboratory testing), vaccination, and other health guidelines, stigma could potentially interfere with self-care. Internalized stigma may be the most modifiable form of stigma through cognitive and behavioral therapies, if it is detected early and remediated.

Considerably less is known about enacted stigma in IBD and is an important area for future research. Enacted stigma evaluated in other conditions demonstrates that it is a very important aspect of public health and health systems.44,116,117 Whether it is subtle “weeding” out of an employee who is chronically ill or more direct (eg, refusing to allow an IBD patient to use the restroom), enacted stigma requires a comprehensive intervention.

Measurement of stigma and related factors is critical to proper detection and potential intervention – unfortunately, the construct itself, when present, makes it hard to measure. One tool specific to IBD is the Perceived Stigma Scale for IBD, adapted from the Perceived Stigma Scale for IBS,86 which allows for quick assessment of stigma perceptions among IBD patients during routine visits. However, as we saw earlier, poor quality of life, poor treatment adherence, or low disease knowledge may also point to stigmatizing beliefs about IBD and when present, the provider should query for perceived stigma. Regardless, it is important for health care providers to ask patients about the social implications of their disease so that they may be referred to appropriate resources, including clinical health psychologists, to help mitigate the potential impacts of stigma on patient outcomes.

The development of stigma interventions has occurred for other chronic conditions,46,118–121 and while their efficacy in reducing stigma is mixed, these interventions have merit. The RAND Corporation and the American Psychological Association have described theoretically-based multicomponent approaches to reducing stigma in mental illness which could be applicable to IBD.122 These include training interventions for health professionals and the general public, which provide information on the causes of the disease (not stress or diet, but an immune-inflammatory reaction), treatments (infusions, surgeries, and ostomies), and experiences of people living with the disease (people with CD and ostomies can be athletes, like Matt Light, David Garrard, and Kevin Dineen). Educational interventions seem to hold the longest staying power when they are enhanced with a direct interpersonal contact strategy (having a guest speaker with UC or a panel discussion between IBD patients from different backgrounds).123 Finally, mass media campaigns can deliver similar antistigma, educational messages although the impact of these is hard to evaluate. Patient advocacy groups have already emerged to help destigmatize IBD (eg, The Great Bowel Movement, www.thegreatbowelmovement.org) and research into their benefit could be an important next step.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Ko JK, Auyeung KK. Inflammatory bowel disease: etiology, pathogenesis and current therapy. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:1082–1096. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fairburn K. Joint involvement in systemic disease. Practitioner. 1994;238:214–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maconi G, Gridavilla D, Vigano C, et al. Perianal disease is associated with psychiatric co-morbidity in Crohn’s disease in remission. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:1285–1290. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-1935-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46–54. e42. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. quiz e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langholz E. Current trends in inflammatory bowel disease: the natural history. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2010;3:77–86. doi: 10.1177/1756283X10361304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vester-Andersen MK, Prosberg MV, Jess T, et al. Disease course and surgery rates in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based, 7-year follow-up study in the era of immunomodulating therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:705–714. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sainsbury A, Heatley RV. Review article: psychosocial factors in the quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:499–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alrubaiy L, Rikaby I, Dodds P, Hutchings HA, Williams JG. Systematic review of health-related quality of life measures for inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:284–292. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Have M, van der Aalst KS, Kaptein AA, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life in Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Floyd DN, Langham S, Severac HC, Levesque BG. The economic and quality-of-life burden of Crohn’s disease in Europe and the United States, 2000 to 2013: a systematic review. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:299–312. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3368-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loftus EV, Jr, Guerin A, Yu AP, et al. Increased risks of developing anxiety and depression in young patients with Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1670–1677. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuller-Thomson E, Lateef R, Sulman J. Robust association between inflammatory bowel disease and generalized anxiety disorder: findings from a nationally representative Canadian study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2341–2348. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nahon S, Lahmek P, Durance C, et al. Risk factors of anxiety and depression in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2086–2091. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graff LA, Walker JR, Bernstein CN. Depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease: a review of comorbidity and management. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1105–1118. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panara AJ, Yarur AJ, Rieders B, et al. The incidence and risk factors for developing depression after being diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease: a cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:802–810. doi: 10.1111/apt.12669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szigethy E, Craig AE, Iobst EA, et al. Profile of depression in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: implications for treatment. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:69–74. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bel LG, Vollebregt AM, Van der Meulen-de Jong AE, et al. Sexual dysfunctions in men and women with inflammatory bowel disease: the influence of IBD-related clinical factors and depression on sexual function. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1557–1567. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis MC. Attributions and inflammatory bowel disease: patients’ perceptions of illness causes and the effects of these perceptions on relationships. AARN News Lett. 1988;44:16–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Eijk I, Stockbrugger R, Russel M. Influence of quality of care on quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): literature review and studies planned. Eur J Intern Med. 2000;11:228–234. doi: 10.1016/s0953-6205(00)00095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright EK, Kamm MA. Impact of drug therapy and surgery on quality of life in Crohn’s disease: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1187–1194. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ananthakrishnan AN, Gainer VS, Cai T, et al. Similar risk of depression and anxiety following surgery or hospitalization for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:594–601. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackner LM, Crandall WV. Long-term psychosocial outcomes reported by children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1386–1392. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drossman DA, Patrick DL, Mitchell CM, Zagami EA, Appelbaum MI. Health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Functional status and patient worries and concerns. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1379–1386. doi: 10.1007/BF01538073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casati J, Toner BB, de Rooy EC, Drossman DA, Maunder RG. Concerns of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a review of emerging themes. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:26–31. doi: 10.1023/a:1005492806777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levenstein S, Li Z, Almer S, et al. Cross-cultural variation in disease-related concerns among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1822–1830. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daniel JM. Young adults’ perceptions of living with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2002;25:83–94. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kappelman MD, Porter CQ, Galanko JA, et al. Utilization of healthcare resources by U.S. children and adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:62–68. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bokemeyer B, Hardt J, Huppe D, et al. Clinical status, psychosocial impairments, medical treatment and health care costs for patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Germany: an online IBD registry. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:355–368. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray WN, Denson LA, Baldassano RN, Hommel KA. Treatment adherence in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: the collective impact of barriers to adherence and anxiety/depressive symptoms. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37:282–291. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magalhaes J, Dias de Castro F, Boal Carvalho P, Leite S, Moreira MJ, Cotter J. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: is your patient at risk of non-adherence? Acta Med Port. 2014;27:576–580. doi: 10.20344/amp.5090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pirinen T, Kolho KL, Simola P, Ashorn M, Aronen ET. Parent-adolescent agreement on psychosocial symptoms and somatic complaints among adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101:433–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turnbull GK, Vallis TM. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: the interaction of disease activity with psychosocial function. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1450–1454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greene BR, Blanchard EB, Wan CK. Long-term monitoring of psychosocial stress and symptomatology in inflammatory bowel disease. Behav Res Ther. 1994;32:217–226. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunnarsson C, Chen J, Rizzo JA, Ladapo JA, Lofland JH. Direct health care insurer and out-of-pocket expenditures of inflammatory bowel disease: evidence from a US national survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:3080–3091. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2289-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rocchi A, Benchimol EI, Bernstein CN, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease: a Canadian burden of illness review. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26:811–817. doi: 10.1155/2012/984575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bassi A, Dodd S, Williamson P, Bodger K. Cost of illness of inflammatory bowel disease in the UK: a single centre retrospective study. Gut. 2004;53:1471–1478. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.041616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gunnarsson C, Chen J, Rizzo JA, Ladapo JA, Naim A, Lofland JH. The employee absenteeism costs of inflammatory bowel disease: evidence from US National Survey Data. J Occup Environ Med. 2013;55:393–401. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31827cba48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saibil F, Lai E, Hayward A, Yip J, Gilbert C. Self-management for people with inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:281–287. doi: 10.1155/2008/428967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooper JM, Collier J, James V, Hawkey CJ. Beliefs about personal control and self-management in 30–40 year olds living with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:1500–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barlow C, Cooke D, Mulligan K, Beck E, Newman S. A critical review of self-management and educational interventions in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2010;33:11–18. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0b013e3181ca03cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keefer L, Kiebles JL, Kwiatek MA, et al. The potential role of a self-management intervention for ulcerative colitis: a brief report from the ulcerative colitis hypnotherapy trial. Biol Res Nurs. 2012;14:71–77. doi: 10.1177/1099800410397629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taft TH, Keefer L, Leonhard C, Nealon-Woods M. Impact of perceived stigma on inflammatory bowel disease patient outcomes. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1224–1232. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parcesepe AM, Cabassa LJ. Public stigma of mental illness in the United States: a systematic literature review. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2013;40:384–399. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0430-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brohan E, Slade M, Clement S, Thornicroft G. Experiences of mental illness stigma, prejudice and discrimination: a review of measures. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:80. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abdullah T, Brown TL. Mental illness stigma and ethnocultural beliefs, values, and norms: an integrative review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:934–948. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stangl AL, Lloyd JK, Brady LM, Holland CE, Baral S. A systematic review of interventions to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination from 2002 to 2013: how far have we come? J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18734. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smit PJ, Brady M, Carter M, et al. HIV-related stigma within communities of gay men: a literature review. AIDS Care. 2012;24:405–412. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.613910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, et al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008;22(Suppl 2):S67–79. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327438.13291.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scambler G, Heijnders M, van Brakel WH, ICRAAS Understanding and tackling health-related stigma. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11:269–270. doi: 10.1080/13548500600594908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marlow LA, Waller J, Wardle J. Does lung cancer attract greater stigma than other cancer types? Lung Cancer. 2015;88:104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mutebi M, Edge J. Stigma, survivorship and solutions: addressing the challenges of living with breast cancer in low-resource areas. S Afr Med J. 2014;104:383. doi: 10.7196/samj.8253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shepherd MA, Gerend MA. The blame game: cervical cancer, knowledge of its link to human papillomavirus and stigma. Psychol Health. 2013;29:94–109. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2013.834057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Noor A, Bashir S, Earnshaw VA. Bullying, internalized hepatitis (hepatitis C virus) stigma, and self-esteem: does spirituality curtail the relationship in the workplace. J Health Psychol. doi: 10.1177/1359105314567211. Epub 2015 Jan 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marinho RT, Barreira DP. Hepatitis C, stigma and cure. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6703–6709. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.6703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moore GA, Hawley DA, Bradley P. Hepatitis C: studying stigma. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2008;31:346–352. doi: 10.1097/01.SGA.0000338279.40412.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bautista RE, Shapovalov D, Shoraka AR. Factors associated with increased felt stigma among individuals with epilepsy. Seizure. 2015;30:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leaffer EB, Hesdorffer DC, Begley C. Psychosocial and socio-demographic associates of felt stigma in epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;37:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thomas SV, Nair A. Confronting the stigma of epilepsy. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2011;14:158–163. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.85873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Garbin CA, Garbin AJ, Carloni ME, Rovida TA, Martins RJ. The stigma and prejudice of leprosy: influence on the human condition. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2015;48:194–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sermrittirong S, Van Brakel WH. Stigma in leprosy: concepts, causes and determinants. Lepr Rev. 2014;85:36–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heijnders ML. The dynamics of stigma in leprosy. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 2004;72:437–447. doi: 10.1489/1544-581X(2004)72<437:TDOSIL>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Papadopoulos S, Brennan L. Correlates of weight stigma in adults with overweight and obesity: a systematic literature review. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23:1743–1760. doi: 10.1002/oby.21187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Yeazel MW, Hellerstedt WL, Griffin JM, van Ryn M. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes Rev. 2015;16:319–326. doi: 10.1111/obr.12266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Callahan D. Children, stigma, and obesity. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:791–792. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Puhl RM, Heuer CA. The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:941–964. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aydemir N, Ozkara C, Unsal P, Canbeyli R. A comparative study of health related quality of life, psychological well-being, impact of illness and stigma in epilepsy and migraine. Seizure. 2011;20:679–685. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bhalla D, Chea K, Hun C, et al. Population-based study of epilepsy in Cambodia associated factors, measures of impact, stigma, quality of life, knowledge-attitude-practice, and treatment gap. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Blume WT, Derry PA. Stigma and its neurological and psychological effects in epilepsy. Can J Neurol Sci. 2008;35:403–404. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100009045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carter-Harris L. Lung cancer stigma as a barrier to medical help-seeking behavior: practice implications. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;27:240–245. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Drapalski AL, Lucksted A, Perrin PB, et al. A model of internalized stigma and its effects on people with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:264–269. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.001322012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Else-Quest NM, LoConte NK, Schiller JH, Hyde JS. Perceived stigma, self-blame, and adjustment among lung, breast and prostate cancer patients. Psychol Health. 2009;24:949–964. doi: 10.1080/08870440802074664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Matthews AK, Corrigan PW, Rutherford JL. Mental illness stigma as a barrier to psychosocial services for cancer patients. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2003;1:375–379. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2003.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:813–821. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Link BG, Phelan J. Conceptualizing stigma. Ann Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Corrigan PW, Watson AC. Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry. 2002;1:16–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boyd JE, Adler EP, Otilingam PG, Peters T. Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale: a multinational review. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:221–231. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van der Beek KM, Bos I, Middel B, Wynia K. Experienced stigmatization reduced quality of life of patients with a neuromuscular disease: a cross-sectional study. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27:1029–1038. doi: 10.1177/0269215513487234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Segalovich J, Doron A, Behrbalk P, Kurs R, Romem P. Internalization of stigma and self-esteem as it affects the capacity for intimacy among patients with schizophrenia. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2013;27:231–234. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hilbert A, Braehler E, Haeuser W, Zenger M. Weight bias internalization, core self-evaluation, and health in overweight and obese persons. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22:79–85. doi: 10.1002/oby.20561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Earnshaw VA, Quinn DM. The impact of stigma in healthcare on people living with chronic illnesses. J Health Psychol. 2012;17:157–168. doi: 10.1177/1359105311414952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jones EE, Farina A, Hastorf AH, Markus H, Miller DT, Scott RA. Social Stigma: The Psychology of Marked Relationships. New York: WH Freeman & Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Crandall CS, Moriarty D. Physical illness stigma and social rejection. Br J Soc Psychol. 1995;34(Pt 1):67–83. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1995.tb01049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sheffield BF, Carney MW. Crohn’s disease: a psychosomatic illness? Br J Psychiatry. 1976;128:446–450. doi: 10.1192/bjp.128.5.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bernstein CN, Singh S, Graff LA, Walker JR, Miller N, Cheang M. A prospective population-based study of triggers of symptomatic flares in IBD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1994–2002. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jones MP, Keefer L, Bratten J, et al. Development and initial validation of a measure of perceived stigma in irritable bowel syndrome. Psychol Health Med. 2009;14:367–374. doi: 10.1080/13548500902865956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Taft TH, Keefer L, Artz C, Bratten J, Jones MP. Perceptions of illness stigma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1391–1399. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9883-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Simren M, Axelsson J, Gillberg R, Abrahamsson H, Svedlund J, Björnsson ES. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in remission: the impact of IBS-like symptoms and associated psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:389–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Van Brakel WH. Measuring health-related stigma – a literature review. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11:307–334. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dibley L, Norton C. Experiences of fecal incontinence in people with inflammatory bowel disease: self-reported experiences among a community sample. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1450–1462. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318281327f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Krause M. The transformation of social representations of chronic disease in a self-help group. J Health Psychol. 2003;8:599–615. doi: 10.1177/13591053030085010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bernhofer EI, Masina VM, Sorrell J, Modic MB. The pain experience of patients hospitalized with inflammatory bowel disease: a phenomenological study. Gastroenterol Nurs. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000137. Epub 2015 Aug 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Czuber-Dochan W, Dibley LB, Terry H, Ream E, Norton C. The experience of fatigue in people with inflammatory bowel disease: an exploratory study. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:1987–1999. doi: 10.1111/jan.12060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Czuber-Dochan W, Norton C, Bredin F, Darvell M, Nathan I, Terry H. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of fatigue experienced by people with IBD. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:835–844. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.de Rooy EC, Toner BB, Maunder RG, et al. Concerns of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results from a clinical population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1816–1821. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Maunder R, Toner B, de Rooy E, Moskovitz D. Influence of sex and disease on illness-related concerns in inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 1999;13:728–732. doi: 10.1155/1999/701645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Joachim G, Acorn S. Stigma of visible and invisible chronic conditions. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:243–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Saunders B. Stigma, deviance and morality in young adults’ accounts of inflammatory bowel disease. Sociol Health Illn. 2014;36:1020–1036. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Frohlich DO. Support often outweighs stigma for people with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2014;37:126–136. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Moody GA, Probert CS, Jayanthi V, Mayberry JF. The attitude of employers to people with inflammatory bowel disease. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34:459–460. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90306-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Finlay DG, Basu D, Sellin JH. Effect of race and ethnicity on perceptions of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:503–507. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200606000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mayberry MK, Probert C, Srivastava E, Rhodes J, Mayberry JF. Perceived discrimination in education and employment by people with Crohn’s disease: a case control study of educational achievement and employment. Gut. 1992;33:312–314. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.3.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wyke RJ, Edwards FC, Allan RN. Employment problems and prospects for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1988;29:1229–1235. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.9.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Moody G, Eaden JA, Mayberry JF. Social implications of childhood Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28:S43–S45. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199904001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Looper KJ, Kirmayer LJ. Perceived stigma in functional somatic syndromes and comparable medical conditions. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Moskovitz DN, Maunder RG, Cohen Z, McLeod RS, MacRae H. Coping behavior and social support contribute independently to quality of life after surgery for inflammatory bowel disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:517–521. doi: 10.1007/BF02237197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Danielsen AK, Burcharth J, Rosenberg J. Patient education has a positive effect in patients with a stoma: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(6):e276–e283. doi: 10.1111/codi.12197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Simmons KL, Smith JA, Bobb KA, Liles LL. Adjustment to colostomy: stoma acceptance, stoma care self-efficacy and interpersonal relationships. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60(6):627–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Voth J, Sirois FM. The role of self-blame and responsibility in adjustment to inflammatory bowel disease. Rehabil Psychol. 2009;54:99–108. doi: 10.1037/a0014739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Salter M. Stoma care. Overcoming the stigma. Nurs Times. 1990;86:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Smith DM, Loewenstein G, Rozin P, Sherriff RL, Ubel PA. Sensitivity to disgust, stigma, and adjustment to life with a colostomy. J Res Pers. 2007;41:787–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Danielsen AK, Soerensen EE, Burcharth K, Rosenberg J. Learning to live with a permanent intestinal ostomy: impact on everyday life and educational needs. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2013;40:407–412. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e3182987e0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Taft TH, Ballou S, Keefer L. A preliminary evaluation of internalized stigma and stigma resistance in inflammatory bowel disease. J Health Psychol. 2013;18:451–460. doi: 10.1177/1359105312446768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Fife BL, Wright ER. The dimensionality of stigma: a comparison of its impact on the self of persons with HIV/AIDS and cancer. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41:50–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mayberry JF. Impact of inflammatory bowel disease on educational achievements and work prospects. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28:S34–36. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199904001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Awofeso N. Concept and impact of stigma on discrimination against leprosy sufferers – minimizing the harm. Lepr Rev. 2005;76:101–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Parfene C, Stewart TL, King TZ. Epilepsy stigma and stigma by association in the workplace. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;15:461–466. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Birbeck G. Interventions to reduce epilepsy-associated stigma. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11:364–366. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bos AE, Schaalma HP, Pryor JB. Reducing AIDS-related stigma in developing countries: the importance of theory- and evidence-based interventions. Psychol Health Med. 2008;13:450–460. doi: 10.1080/13548500701687171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Brabcova D, Lovasova V, Kohout J, Zarubova J, Komarek Improving the knowledge of epilepsy and reducing epilepsy-related stigma among children using educational video and educational drama – a comparison of the effectiveness of both interventions. Seizure. 2013;22:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chambers SK, Morris BA, Clutton S, et al. Psychological wellness and health-related stigma: a pilot study of an acceptance-focused cognitive behavioural intervention for people with lung cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2015;24:60–70. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Thornicroft G, Mehta N, Clement S, et al. Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. Lancet. 2015 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Heijnders M, Van Der Meij S. The fight against stigma: an overview of stigma-reduction strategies and interventions. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11:353–363. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]