Abstract

Background

Only limited data is present regarding the incidence and prognostic implications of acute kidney injury (AKI) in ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients with preserved left ventricular (LV) function in the primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) era.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of 842 consecutive STEMI patients with preserved LV function (ejection fraction ≥50%, assessed by echocardiography) who underwent primary PCI between January 2008 and January 2015. AKI was defined as an increase of ≥0.3 mg/dl in serum creatinine within 48 h following admission. Patients were assessed for all-cause mortality up to 5 years.

Results

Fifty-two patients (6.2%) developed AKI. Patients with AKI were older, had impaired baseline renal function, and presented more often with heart failure throughout their hospitalization. Patients with AKI had a higher 5-year all-cause mortality (13.4 vs. 2.4%, p < 0.001). Compared to patients with no AKI, the adjusted hazard ratio for all-cause mortality was 2.64 (95% CI 1.25-5.56, p = 0.01).

Conclusions

Among STEMI patients with preserved LV function undergoing primary PCI, AKI is associated with a higher long-term mortality.

Key Words: Acute kidney injury, ST elevation myocardial infarction, Percutaneous coronary intervention, Ejection fraction

Introduction

Worsening of renal function is a frequent complication among ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) known to be associated with adverse outcomes [1,2,3,4]. Recent evidence suggested that among this patient population acute kidney injury (AKI) is related to an acute left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction [5] and hemodynamic compromise [6] resulting in reduced renal perfusion, in addition to contrast-induced nephropathy [7,8,9]. Limited and conflicting data is present regarding the incidence and prognostic implications of AKI in STEMI patients with preserved (ejection fraction ≥50%) LV function [10,11]. Our aim was to determine the possible prognostic effect of AKI in patients with preserved LV function in a large cohort of STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI.

Methods

Study Population

We performed a retrospective, single-center observational study at the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, a tertiary referral hospital with a 24/7 primary PCI service as was described previously [1,5,6]. Included were all consecutive patients admitted to the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit between January 2008 and January 2015 with a diagnosis of acute STEMI. Patients who were treated either conservatively or by thrombolysis and those whose final diagnosis on discharge was other than STEMI (e.g. myocarditis or Takotsubo cardiomyopathy) were excluded. We also excluded all patients who died within 30 days of hospital admission, as well as patients requiring chronic peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis treatment. The initial cohort included 1,704 patients whose baseline demographics, cardiovascular history, clinical risk factors, treatment characteristics, and laboratory results were all retrieved from the hospital electronic medical records.

Protocol

A diagnosis of STEMI was established in accordance with published guidelines including a typical chest pain history, diagnostic electrocardiographic changes, and serial elevation of cardiac biomarkers [12]. The study protocol was approved by the local institutional ethics committee. Primary PCI was performed on patients with symptoms of ≤12 h duration as well as in patients with symptoms lasting 12-24 h if the symptoms persisted at the time of admission. Following coronary interventional procedures, physiologic (0.9%) saline was given intravenously at a rate of 1 ml/kg/h for 12 h after contrast exposure. In patients with overt heart failure, the hydration rate was reduced at the discretion of the attending physician. The contrast medium used in procedures was iodixanol (Visipaque, GE Healthcare, Ireland) or iohexol (Omnipaque, GE Healthcare). Heart failure was defined as clinical or radiographic evidence of pulmonary congestion. All patients underwent a screening echocardiographic examination within 3 days of admission. Echocardiography was performed by Philips IE-33 equipped with S5-1 transducers (Philips Healthcare, Andover, Mass., USA) and GE Vivid 7 model equipped with M4S transducer. LV diameters and interventricular septal and posterior wall widths were measured from the parasternal short axis by means of a two-dimensional, or a two-dimensional-guided, M-mode echocardiogram of the left ventricle at the papillary muscle level using the parasternal short-axis view [13]. LV ejection fraction was calculated by the biplane method. The 16-segment model was used for scoring the severity of segmental wall motion abnormalities according to the American Society of Echocardiography [14]. Patients whose echocardiographic assessment demonstrated LV ejection fraction <50% (n = 862) were also excluded, and thus the final study population included 842 patients.

The serum creatinine (sCr) level was determined upon hospital admission and at least once a day during the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit stay and was available for all analyzed patients. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was estimated using the abbreviated Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation [15]. Baseline renal insufficiency was categorized as an admission eGFR of ≤60 ml/min/1.73 m2[16]. AKI was determined using the AKI network (AKIN) criteria [17] and defined as a sCr rise of >0.3 mg/dl compared with admission sCr. Mortality was assessed over a median period of 1,225 ± 511 days (range 31-2,250) up to April 1, 2015. Assessment of survival following hospital discharge was determined from computerized records of the population registry bureau.

Statistical Analysis

All data were summarized and displayed as means (± SD) for continuous variables and as numbers (percentages) of patients in each group for categorical variables. The p values for the χ2 test were calculated with Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables were compared using the independent samples t test or Mann-Whitney test. The identification of independent predictors of AKI was assessed using logistic regression. A binary logistic regression model was performed using the enter mode. The model was adjusted for age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, past or present smoking history, baseline eGFR ≤60 ml/min/1.73 m2, clinical heart failure, admission C-reactive protein (CRP) level, and use of intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation (IABC) to support PCI. The influence of AKI on the occurrence of all-cause mortality was evaluated using multivariate Cox regression. We adjusted for age, gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking status, baseline eGFR ≤60 ml/min/1.73 m2, clinical heart failure, admission CRP level, use of IABC, and AKI status. A two-tailed p value <0.05 was considered significant for all analyses. All analyses were performed with the SPSS 20.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill., USA).

Results

A total of 842 STEMI patients treated by primary PCI were enrolled in the study, 52 (6.1%) of whom developed AKI in accordance with the AKIN criteria. The median time to echocardiography was 1.4 days (interquartile range 1-2). The baseline clinical characteristics of patients with and without AKI are listed in table 1. Patients with AKI were more likely to be older, hypertensive, with lower baseline eGFR, and more likely to have heart failure throughout their hospitalization. Patients with AKI received less contrast volume during primary PCI; however, no significant difference in the contrast volume/eGFR ratio was found between patients with and without AKI. Following the performance of a logistic multivariate analysis model, independent predictors of AKI included baseline eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 [odds ratio (OR) 2.56, 95% CI 1.44-4.53, p = 0.001], heart failure (OR 4.88, 95% CI 2.78-8.59, p = 0.001), CRP (OR 1.01, 95% 1.001-1.013, p = 0.02), and IABC insertion (OR 2.49, 95% CI 1.03-6.01, p = 0.04; table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| AKI |

p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| no (n = 790) | yes (n = 52) | |||

| Age, years | 60 ± 12 | 67 ± 12 | <0.001 | |

| Men | 649 (82) | 38 (73) | 0.137 | |

| Hypertension | 333 (42) | 34 (65) | 0.001 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 387 (49) | 27 (52) | 0.775 | |

| Smoking | 429 (54) | 19 (37) | 0.01 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 160 (20) | 15 (29) | 0.157 | |

| Family history | 146 (18) | 8 (15) | 0.576 | |

| Admission eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 74 ± 18 | 63 ± 21 | <0.001 | |

| Admission eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 | 131 (17) | 25 (48) | <0.001 | |

| Admission systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 136 ± 19 | 133 ± 28 | 0.204 | |

| Admission diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg Number of narrowed coronary arteries | 81 ± 13 | 79 ± 11 | 0.596 | |

| 1 | 346 (44) | 23 (44) | 0.416 | |

| 2 | 268 (34) | 13 (25) | ||

| 3 | 176 (22) | 16 (31) | ||

| Heart failure during hospitalization | 14 (2) | 8 (15) | <0.001 | |

| Peak CPK, IU/l | 887 ± 911 | 1,039 ± 1,256 | 0.257 | |

| Contrast volume, ml | 144 ± 44 | 111 ± 34 | 0.005 | |

| Contrast volume/eGFR ratio | 1.94 ± 0.44 | 1.76 ± 0.61 | 0.656 | |

| Admission CRP, mg/dl | 8.92 ± 19.7 | 8.52 ± 9.52 | 0.932 | |

| IABC insertion | 2 (0) | 5 (10) | <0.001 | |

| LV ejection fraction | 54 ± 4 | 53 ± 4 | 0.03 | |

Values are means ± SD or n (%). CPK = Creatine phosphokinase.

Table 2.

Predictors of AKI in STEMI

| Correlates | OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.028 | 1.003–1.053 | 0.03 |

| Hypertension | 1.47 | 0.88–2.42 | 0.135 |

| eGFR ≤60 ml/min/1.73 m2 | 2.56 | 1.44–4.53 | 0.001 |

| Smoking | 0.58 | 0.52–1.43 | 0.865 |

| Heart failure | 4.88 | 2.78–8.59 | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.04 | 0.61–1.78 | 0.865 |

| CRP | 1.01 | 1.001–1.013 | 0.02 |

| IABP insertion | 2.49 | 1.03–6.01 | 0.04 |

Long-Term Outcome

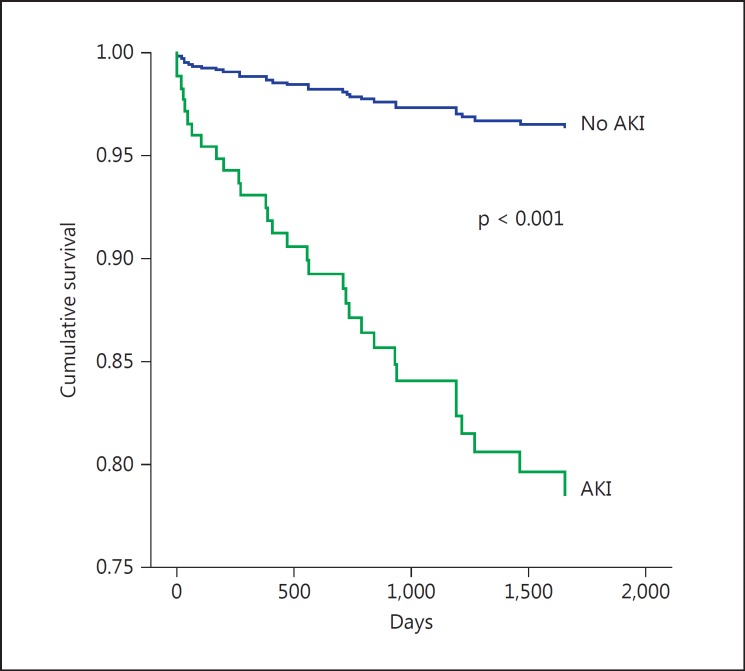

Over a mean period of 3.3 ± 1.4 years, 26 (3.0%) patients of the entire cohort died. Figure 1 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival curve for long-term survival according to the presence or absence of AKI. Mortality was significantly higher among those with AKI (7/52, 13.4%) following STEMI than those without AKI (19/790, 2.4%, p = 0.001). In the Cox regression model for all-cause mortality, AKI was an independent predictor of mortality reaching a hazard ratio of 2.64 (95% CI 1.25-5.56, p = 0.01) compared to patients without AKI. Other predictors of mortality included age, heart failure, CRP, and need for IABC insertion (table 3).

Fig. 1.

Cumulative survival rates for 842 patients with STEMI with preserved LV function with and without AKI (unadjusted hazard ratio 6.44, 95% CI 2.96-14.01, p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Predictors of all-cause mortality in STEMI

| Correlates | HR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.045 | 1.02–1.08 | 0.02 |

| Gender | 1.95 | 0.94–4.04 | 0.07 |

| Hypertension | 0.56 | 0.26–1.25 | 0.16 |

| Smoking | 0.79 | 0.37–1.68 | 0.544 |

| eGFR ≤60 ml/min/1.73 m2 | 2.79 | 1.29–6.00 | 0.009 |

| Heart failure | 3.86 | 1.83–8.15 | 0.001 |

| AKI | 2.64 | 1.25–5.56 | 0.01 |

| CRP | 1.01 | 1.004–1.015 | 0.001 |

| IABC insertion | 4.51 | 2.05–9.97 | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.51 | 0.74–3.08 | 0.257 |

HR = Hazard ratio.

Discussion

In this cohort of STEMI patients undergoing PCI with preserved LV function, the occurrence of AKI following primary PCI, while being much less frequent than previously reported, still maintained its negative prognostic impact. This finding highlights the detrimental effect of AKI, even in patients considered previously to have a better outcome. The sudden myocardial insult in STEMI with a subsequent acute reduction of cardiac output leads to reduced effective renal blood flow, consequently causing renal hypoxia and the synthesis of reactive oxygen species. Following the resumption of coronary flow and the improvement of LV function as well as the resolution of acute arrhythmias, hemodynamic impairment often resolves while renal function may still remain impaired or lag in recovery. Contrast material is still considered a major reason for AKI development in STEMI patients following PCI. Contrast-induced AKI is a prevalent and deleterious complication of coronary angiography and reported to be the third most common cause of hospital-acquired renal failure [7,8,9]. The contrast volume/eGFR ratio, recently shown to be a better predictor of AKI among patients undergoing PCI [18,19], was not found to differ significantly between patients with and without AKI development in our cohort. This finding points to the possible impact of other factors besides contrast volume and reduced renal perfusion on the development of AKI in the setting of STEMI. These include anemia [20], elevated CRP [21], and admission hyperglycemia [22], all shown to possibly harm renal function in STEMI patients. Even small differences in renal function within the normal range have been shown to be related to adverse outcomes [23]. Only limited data is present on the possible prognostic effect of AKI following primary PCI on patients with preserved LV function. Pyxaras et al. [10] reported that among 387 STEMI patients with preserved (ejection fraction >40%) LV function following primary PCI, the occurrence of AKI was associated with worse 1-year outcomes. In this cohort, however, the standard definition for AKI was not used. Moreover, the quantitative assessment of LV function was performed using angiography in the vast majority of patients, rather than echocardiography, thus being less accurate and missing potential improvement in acute LV stunning following PCI. A report by Lazzeri et al. [11] demonstrated that among STEMI patients with preserved (ejection fraction >45%) LV function submitted to primary PCI, worsening renal function was associated with increased early death but not with a poorer survival rate at long-term follow-up. Our findings highlight that the development of AKI in STEMI patients with preserved LV function identifies a subset of higher-risk patients who are older, hypertensive, with more baseline renal insufficiency, inflammatory activation, and heart failure complicating the hospitalization. The data strongly supports the implementation of dedicated renal protection protocols even among STEMI patients with preserved LV function [24,25] and suggests the clinical need of a close monitoring of renal function and of a more intensive treatment in those who develop AKI [26].

We acknowledge several important limitations of our study. First, this was a single-center retrospective and nonrandomized observational study and may have been subject to bias, even though we included consecutive patients and attempted to adjust for confounding factors using the multivariate regression model. Second, the definition of the AKIN criteria refers to sCr change within a time frame of 48 h [17]. As the change in sCr can lag beyond this period due to delayed effects of contrast material and drugs, worsening of renal function might have occurred following hospital discharge in some patients, thus the true incidence of AKI described in our study may have been underestimated. Echocardiographic systolic function early after primary PCI may still represent stunned myocardium which may theoretically recover, thus overestimating the true severity of LV function. Finally, as data regarding concomitant use of statins, renin/angiotensin blockers, β-blockers, and antiaggregants prior to hospital admission and upon discharge was not available for many patients, their effect on long-term outcomes could not been assessed. No information was present on other end points including recurrent myocardial infarction, need for repeat revascularization, heart failure, stroke, and need for chronic dialysis.

In conclusion, among STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI and with preserved LV function, AKI is associated with a higher long-term mortality.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Shacham Y, Leshem-Rubinow E, Steinvil A, Assa EB, Keren G, Roth A, Arbel Y. Renal impairment according to Acute Kidney Injury Network criteria among ST elevation myocardial infarction patients undergoing primary percutaneous intervention: a retrospective observational study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2014;103:525–532. doi: 10.1007/s00392-014-0680-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg A, Hammerman H, Petcherski S, Zdorovyak A, Yalonetsky S, Kapeliovich M, Agmon Y, Markiewicz W, Aronson D. Inhospital and 1-year mortality of patients who develop worsening renal function following acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2005;150:330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parikh CR, Coca SG, Wang Y, Masoudi FA, Krumholz HM. Long-term prognosis of acute kidney injury after acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:987–995. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.9.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amin AP, Spertus JA, Reid KJ, Lan X, Buchanan DM, Decker C, Masoudi FA. The prognostic importance of worsening renal function during an acute myocardial infarction on long-term mortality. Am Heart J. 2010;160:1065–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shacham Y, Leshem-Rubinow E, Topilsky Y, Steinvil A, Keren G, Roth A, Arbel Y. Association of left ventricular function and acute kidney injury among ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients treated by primary percutaneous intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2014;115:293–297. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shacham Y, Leshem-Rubinow E, Gal-Oz A, Arbel Y, Keren G, Roth A, Steinvil A. Acute cardio-renal syndrome as a cause for renal deterioration among myocardial infarction patients treated by primary percutaneous intervention. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:1240–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.James MT, Samuel SM, Manning MA, Tonelli M, Ghali WA, Faris P, Knudtson ML, Pannu N, Hemmelgarn BR. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury and risk of adverse clinical outcomes after coronary angiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:37–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.974493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurm HS, Dixon SR, Smith DE, Share D, Lalonde T, Greenbaum A, Moscucci M, BMC2 (Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium) Registry Renal function-based contrast dosing to define safe limits of radiographic contrast media in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:907–914. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seeliger E, Sendeski M, Rihal CS, Persson PB. Contrast-induced kidney injury: mechanisms, risk factors, and prevention. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2007–2015. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pyxaras SA, Sinagra G, Mangiacapra F, Perkan A, Di Serafino L, Vitrella G, Rakar S, De Vroey F, Santangelo S, Salvi A, Toth G, Bartunek J, De Bruyne B, Wijns W, Barbato E. Contrast-induced nephropathy in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention without acute left ventricular ejection fraction impairment. Am J Cardiol. 2013;5:684–688. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lazzeri C, Valente S, Chiostri M, Picariello C, Attanà P, Gensini GF. ST-elevation myocardial infarction with preserved ejection fraction: the impact of worsening renal failure. Int J Cardiol. 2012;155:170–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE, Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA, Granger CB, Krumholz HM, Linderbaum JA, Morrow DA, Newby LK, Ornato JP, Ou N, Radford MJ, Tamis-Holland JE, Tommaso CL, Tracy CM, Woo YJ, Zhao DX, Anderson JL, Jacobs AK, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Brindis RG, Creager MA, DeMets D, Guyton RA, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Ohman EM, Stevenson WG, Yancy CW. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;61:e78–e140. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, Sutton MS, Stewart WJ. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiller NB, Shah PM, Crawford M, DeMaria A, Devereux R, Feigenbaum H, Gutgesell H, Reichek N, Sahn D, Schnittger I. Recommendations for quantitation of the left ventricle by two-dimensional echocardiography. American Society of Echocardiography Committee on Standards, Subcommittee on Quantitation of Two-Dimensional Echocardiograms. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1989;2:358–367. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(89)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Kidney Foundation (NKF) Kidney Disease Outcome Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) Advisory Board K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S1–S266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levin A, Warnock DG, Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C. Improving outcomes from acute kidney injury: report of an initiative. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50:1–4. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abe D, Sato A, Hoshi T, Kakefuda Y, Watabe H, Ojima E, Hiraya D, Harunari T, Takeyasu N, Aonuma K. Clinical predictors of contrast-induced acute kidney injury in patients undergoing emergency versus elective percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ J. 2014;78:85–91. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-13-0574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mager A, Vaknin Assa H, Lev EI, Bental T, Assali A, Kornowski R. The ratio of contrast volume to glomerular filtration rate predicts outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;78:198–201. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shacham Y, Gal-Oz A, Leshem-Rubinow E, Arbel Y, Flint N, Keren G, Roth A, Steinvil A. Association of admission hemoglobin levels and acute kidney injury among myocardial infarction patients treated with primary percutaneous intervention. Can J Card. 2015;31:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shacham Y, Leshem-Rubinow E, Steinvil A, Keren G, Roth A, Arbel Y. High sensitive C-reactive protein and the risk of acute kidney injury among ST elevation myocardial infarction patients undergoing primary percutaneous intervention. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2015;19:838–843. doi: 10.1007/s10157-014-1071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shacham Y, Gal-Oz A, Leshem-Rubinow E, Arbel Y, Keren G, Roth A, Steinvil A. Admission glucose levels and the risk of acute kidney injury in nondiabetic ST segment elevation myocardial infarction patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiorenal Med. 2015;5:191–198. doi: 10.1159/000430472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arbel Y, Halkin A, Finkelstein A, Revivo M, Berliner S, Herz I, Keren G, Banai S. Impact of estimated glomerular filtration rate on vascular disease extent and adverse cardiovascular events in patients without chronic kidney disease. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:1374–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao JL, Yang YJ, Zhang YH, You SJ, Wu YJ, Gao RL. Effect of statins on contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty. Int J Cardiol. 2008;126:435–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.01.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ueda H, Yamada T, Masuda M, Okuyama Y, Morita T, Furukawa Y, Koji T, Iwasaki Y, Okada T, Kawasaki M, Kuramoto Y, Naito T, Fujimoto T, Komuro I, Fukunami M. Prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy by bolus injection of sodium bicarbonate in patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing emergent coronary procedures. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1163–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shacham Y, Rofe M, Leshem-Rubinow E, Gal-Oz A, Arbel Y, Keren G, Roth A, ben-Assa E, Halkin A, Finkelstein A, Banai S, Steinvil A. Usefulness of urine output criteria for early detection of acute kidney injury after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Cardiorenal Med. 2014;4:155–160. doi: 10.1159/000365936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]