Summary

In the esophagus two different kinds of primary neoplasias may arise: squamocellular carcinomas (SCC) and esophageal adenocarcinomas (EAC). Although both types of carcinoma are rare diseases, especially the incidence of EAC rose in the last years. The management of esophageal cancer is challenging. There are no specific symptoms of early esophageal cancers. Due to this fact, most of the esophageal cancers are found incidentally, and only 12.5% of esophageal tumors are endoscopically resectable. Gastroscopy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of esophageal cancer. The sensitivity of detecting early-stage carcinoma may be improved by adjunct techniques such as chromoendoscopy, virtual chromoendoscopy, magnification endoscopy, and other advanced endoscopic imaging techniques. The diagnosis of esophageal cancer can be verified with targeted biopsies. Accurate staging information is crucial for establishing appropriate treatment choices for esophageal cancer, while the depth of the tumor determines the feasibility of therapy. In terms of staging, endosonography, abdominal ultrasound, and computed tomography scan of the thorax and abdomen should thus be performed before initiation of therapy.

Keywords: Diagnostics, Esophageal cancer, Adenocarcinoma, Squamocellular carcinoma

Introduction

In the esophagus, two different kinds of primary neoplasias may arise: squamocellular carcinomas (SCC) and esophageal adenocarcinomas (EAC). While the development of SCC is associated with tobacco and alcohol abuse, n-nitrosamines, alkali burn, and achalasia, the major risk factors for EAC are reflux disease and body mass index (BMI). Although SCC is in general more common than EAC, the incidence of EAC is rising very fast in Western countries [1,2,3,4]. Overall, the national cancer report 2010 issued by the Robert Koch Institute showed an incidence of 5,200 for esophageal carcinoma in Germany - with a 4:1 preponderance in male patients. For 2014, even 5,400 male and 1,500 female patients are estimated [1].

Risk Factors for Esophageal Cancer

Adenocarcinoma

In comparison with common carcinomas like colonic or liver cancers, esophageal carcinoma has a lower incidence in Western countries. Population-based studies in the USA from 2003 to 2007 estimate the incidence of EAC to be 5.31/100,000 [5]. Men are eight times more likely than women to be diagnosed with EAC.

-

(1)

How does EAC develop? There is a lot of evidence that most EAC develop from progressive dysplastic changes within Barrett's epithelium (BE). The development of BE is believed to be a reparative response to reflux-induced damage to the native squamous epithelium, with subsequent replacement with a metaplastic intestinal epithelium, i.e. BE. Development of BE is strongly associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and obesity. Metaplastic BE is associated with increased cellular proliferation and turnover that may result in progression to neoplasia. Early studies reported a 30- to 40-fold increased risk of the development of EAC [6]. However, estimates of the risk of EAC associated with BE have been steadily decreasing in more recent, better controlled trials. In a recent population-based cohort study, the presence of BE conferred a relative risk of EAC of 11.3 when compared with that of the general population (95% confidence interval (CI): 8.8-14.4) [7]. Although some caution should be exercised in the interpretation of this analysis because of its retrospective nature and relatively short mean follow-up period of 5 years, these findings are consistent with the trend of decreasing risk estimates observed in multiple other studies over the past 5-10 years [8], although an optimal prospective study has not been conducted yet.

-

(2)

BE is histologically graded as nondysplastic (NDBE), low-grade dysplasia (LGD), high-grade dysplasia (HGD), or invasive EAC [9]. Endoscopically, BE has a characteristic appearance which is described as a salmon or pink color in contrast to the light gray appearance of esophageal squamous mucosa. However, it should be emphasized that histologic examination of esophageal biopsy samples is required to confirm the diagnosis of BE.

Major risk factors for BE and EAC include GERD, white race, smoking, and obesity. Patients with long-standing or severe GERD have a much higher risk of developing EAC (odds ratio (OR) 43.5; 95% CI: 18.3-103.5) than the general population. There is a strong association of GERD and obesity. Therefore, it is no surprise that a BMI of 25 kg/m2 is also associated with an OR of 1.52 (95% CI: 1.15-2.01) for developing EAC, and a BMI > 30 kg/m2 increases the OR to 2.78 (95% CI: 1.85-4.16) [5,10].

-

(3)

Endoscopic screening for BE is controversial because no randomized controlled trial (RCT) has demonstrated a decrease in mortality, neither in general nor due to EAC, as a result of screening [11,12]. Because of the lack of RCT evidence regarding the efficacy of screening, some studies have used models in an attempt to establish a rationale for screening for BE. One such cost-effectiveness model of an esophagogastric duodenoscopy screening of 50-year-old white men with GERD, with surveillance reserved for those with dysplastic BE, demonstrated that USD 10,440 per quality-adjusted life-year could be saved with screening compared with no screening or surveillance [13].

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

SCC of the esophagus is the predominant histologic type of e-sophageal cancer outside Western countries. Incidence rates in China and some parts of Africa are estimated to be as high as 140 per 100,000 [14]. However, in the United States and in Europe, the incidence is much lower and ranges at about 3/100,000 with a declining trend [14]. Men and women are affected equally in high-incidence areas [15]. Alcohol abuse is a known risk factor for SCC when ingestion exceeds 170 g/week. The risk increases in a linear fashion with increasing consumption [16]. Smokers have a nine-fold risk of developing SCC in comparison with nonsmokers (hazard ratio 9.3; 95% CI: 4.0-21.3) [15]. Other risk factors for SCC include a history of aerodigestive cancers, a history of caustic ingestion, and achalasia.

Diagnosis

The management of esophageal cancer is challenging not only in terms of identifying patients at high risk but also because of the overall poor prognosis of the disease. While cancers diagnosed by means of a BE surveillance program or by incidental finding during a gastroscopy performed for another reason may be at an early stage, most esophageal cancers are diagnosed after symptoms like dysphagia develop and tumors are locally advanced. Therefore, only one out of eight esophageal cancers is identified at an early stage (T1) [1]. Typical symptoms of esophageal carcinoma are dysphagia (reduction of esophagus lumen to 50%) [17], vomiting, loss of body weight, and gastrointestinal bleeding [18].

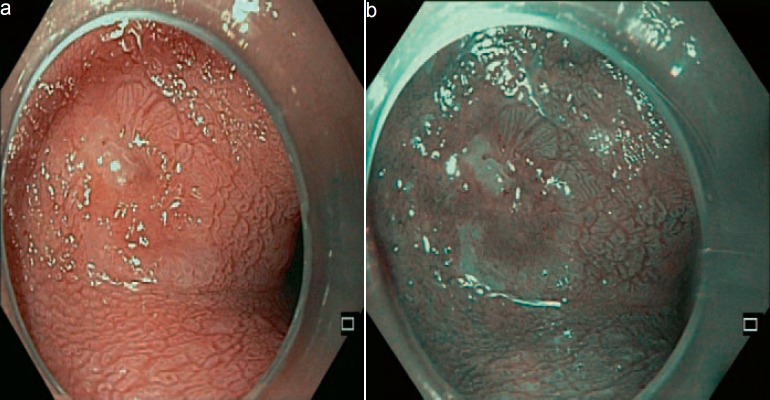

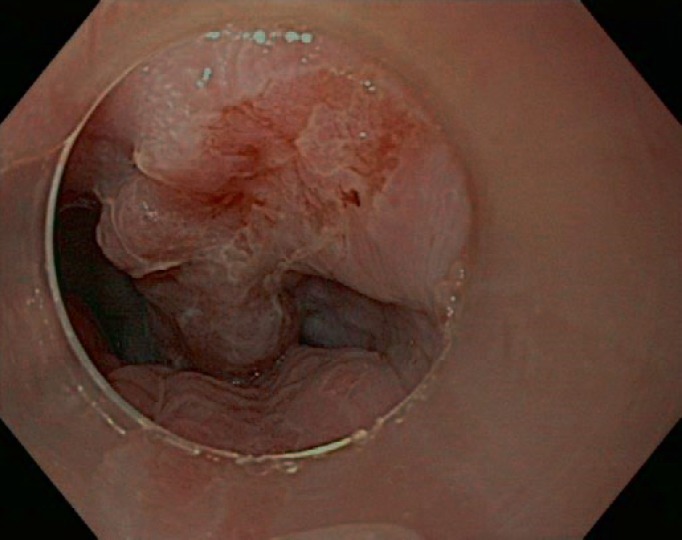

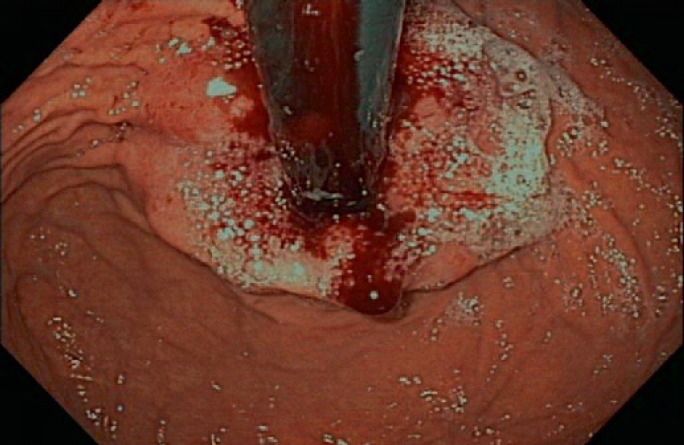

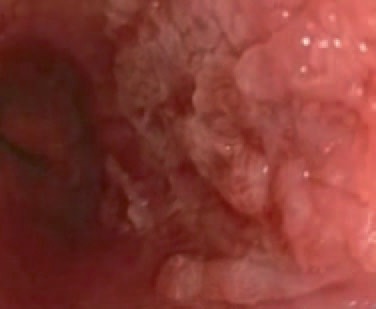

Gastroscopy unveils mucosal irregularities with high-resolution white-light endoscopy. If erosions, ulcers, strictures, or metaplasia are found, the endoscopist has to decide whether the origin of these changes is nonneoplastic or neoplastic. Dysplastic signs are discolorations, fine granulated surfaces (orange peel effect), as well as small elevations and troughs in the Barrett layer. A landscape shape and discrete erosion such as defects are typical of HGD, too (fig. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

Fig. 1.

Advanced esophageal cancer.

Fig. 2.

Native image of an SCC of the esophagus.

Fig. 3.

Early Barrett's adenocarcinoma with acetic acid and virtual chromoendoscopy.

Fig. 4.

Borderline endoscopically resectable Barrett's adenocarcinoma T1 sm3 tumor.

Fig. 5.

Advanced carcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction.

The sensitivity of detecting early-stage carcinoma may be improved by adjunct techniques such as chromoendoscopy (acetic acid 1.5-3% for EAC, lugol solution 0.5-1% for SCC), virtual chromoendoscopy (no significant differences between both groups in the detection of Barrett's carcinoma [19]), magnification endoscopy, and other advanced endoscopic imaging techniques. A prospectively designed study investigated the context in which and the method by which early neoplasias in BE are diagnosed during routine outpatient endoscopy. The three main findings were: i) in patients with short-segment Barrett's esophagus almost all early tumors are diagnosed by index endoscopy and not by Barrett's surveillance; ii) around 40% of all early neoplasias are endoscopically invisible and are only diagnosed using four-quadrant biopsies; iii) the macroscopic tumor type has a substantial influence on the detection rate for neoplasia [20].

Corresponding to the origin of the neoplasia, SCC will be found more likely in the upper and middle part of the esophagus whereas EAC will be detected in the lower part of the esophagus.

A targeted biopsy can be performed in suspect areas to ensure the diagnosis of the endoscopist [21]. Due to the fact that the sensitivity for mucosal biopsies to detect esophageal carcinoma reaches 96% when multiple samples are obtained [22], a minimum of eight biopsies should be taken from the margins and the center of the lesion. An alternative is diagnostic mucosa resection [23].

Staging of Esophageal Malignancies

Accurate staging information is crucial in order to establish appropriate treatment choices for esophageal cancer. The depth of the tumor determines the feasibility of endoscopic management or whether to establish tumor margins and/or lymph node involvement before possible surgical resection or chemoradiation. Complete staging of esophageal cancer traditionally involves endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) in conjunction with cross-sectional imaging. Numerous studies have demonstrated the superiority of EUS in both local tumor (T) and nodal (N) staging over computed tomography (CT) [24]. Accuracy for T staging approaches 90% in superficial and partially obstructing esophageal cancers [25]; however, accuracy declines in cases of completely obstructing tumors that prevent the echoendoscope from traversing the tumor [25]. Endosonographic characteristics of malignant lymph nodes include size >10 mm, round and smooth features, proximity to the primary tumor, and hypoechogenicity. The accuracy of EUS for nodal staging based solely on these acoustic criteria approaches 80% [26,27]. FNA of lymph nodes increases nodal staging accuracy to 92-98% by using pathologic staging as the criterion standard [27,28]. Tissue sample contamination may occur when the endoscope traverses the tumor, and it must be taken into account that false-positive FNA is possible when detached malignant cells that are present within the gastrointestinal lumen are picked up by the needle [29].

An abdominal ultrasound and a multi-slice CT scan of the thorax and abdomen are required for staging the tumor before therapy is initiated.

Disclosure Statement

There are no competing interests of the affiliated authors.

References

- 1.Robert Koch-Institut . Krebs in Deutschland. ed 9. Berlin: Gesellschaft der epidemiologischen Krebsregister e.V. (GEKID) und Zentrum für Krebsregisterdaten (ZfKD) im Robert Koch-Institut; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB, Kvapil P, Hacken-Bitar J, Kramer JR. Abdominal obesity and the risk of Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastro. 2005;100:2151–2156. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown LM, Devesa SS. Epidemiologic trends in esophageal and gastric cancer in the United States. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2002;11:235–256. doi: 10.1016/s1055-3207(02)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pohl H, Welch HG. The role of overdiagnosis and reclassification in the marked increase of esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:142–146. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abrams JA, Sharaiha RZ, Gonsalves L, Lightdale CJ, Neugut Al. Dating the rise of esophageal adenocarcinoma: analysis of Connecticut Tumor Registry data, 1940-2007. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:183–186. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van der Veen AH, Dees J, Blankensteijn JD, Van Blankenstein M. Adenocarcinoma in Barrett's oesophagus: an overrated risk. Gut. 1989;30:14–18. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hvid-Jensen F, Pedersen L, Drewes AM, Sorensen HT, Funch-Jensen P. Incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett's esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1375–1383. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubenstein JH, Scheiman JM, Sadeghi S, Whiteman D, Inadomi JM. Esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence in individuals with gastroesophageal reflux: synthesis and estimates from population studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:254–260. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hornick JL, Odze RD. Neoplastic precursor lesions in Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2007;36:775–796. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, Nyrén O. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:825–831. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903183401101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corley DA, Levin TR, Habel LA, Weiss N, Buffler PA. Surveillance and survival in Barrett's adenocarcinomas: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:633–640. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bytzer P, Christensen PB, Damkier P, Vinding K, Seersholm N. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and Barrett's esophagus: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:86–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inadomi JM, Sampliner R, Lagergren J, Lieberman D, Fendrick AM, Vakil N. Screening and surveillance for Barrett's esophagus in high-risk groups: a cost-utility analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:176–186. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook MB, Kamangar F, Whiteman DC, et al. Cigarette smoking and adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: a pooled analysis from the international BEACON consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1344–1353. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson LA, Cantwell MM, Watson RG, Johnston BT, Murphy SJ, Ferguson HR, McGuigan J, Comber H, Reynolds JV, Murray LJ. The association between alcohol and reflux esophagitis, Barrett's esophagus, and e-sophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:799–805. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pandeya N, Williams G, Green AC, Webb PM, Whiteman DC. Alcohol consumption and the risks of adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1215–1224. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aymaz S, Huegle U, Mueller-Gerbes D, Dormann A. Maligne Obstruktion im Gastrointestinaltrakt. Gastroenterologe. 2011;6:387–393. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behrens A, Pech O, Graupe F, May A, Lorenz D, Ell C. Barrett-Karzinom der Speiseröhre: Prognoseverbesserung durch Innovationen in Diagnostik und Therapie. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:313–319. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pohl J, May A, Rabenstein T, Pech O, Ngyuen-Tat M, Fissler-Eckhoff A, Ell C. Comparison of computed virtual chromoendoscopy with acetic acid for detection of neoplasia in Barrett's esophagus. Endoscopy. 2007;39:594–598. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Behrens A, May A, Wuthnow E, Manner H, Pohl J, Ell C, Pech O. Detecting early neoplasia in Barrett's oesophagus - focus attention on index endoscopy in short-segment-Barrett's oesophagus with random biopsies (Article in German) Z Gastroenterol. 2015;53:568–572. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1399177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gossner L, Ell C.Refluxösophagitis und prämaligne Läsionen des ÖsophagusLeitlinien der DGVS.www.dgvs.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Leitlinien/richtlinienempfehlungen/2.1.Oesophagitis-praemaligneLaesionen.pdf

- 22.Evans JA, Early DS, Chandraskhara V. The role of endoscopy in the assessment and treatment of esophageal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrison R, Perry I, Haddadin W, McDonald S, Bryan R, Abrams K, Sampliner R, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P, Jankowski JA. Detection of intestinal metaplasia in Barrett's esophagus: an observational comparator study suggests the need for a minimum of eight biopsies. Am J Gastro. 2007;102:1154–1161. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors. ed 7. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Catalano MF, Van Dam J, Sivak MV., Jr Malignant e-sophageal strictures: staging accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:535–539. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Dam J, Rice TW, Catalano MF, Kirby T, Sivak MV., Jr High-grade malignant stricture is predictive of esophageal tumor stage. Risks of endosonographic evaluation. Cancer. 1993;71:2910–2917. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930515)71:10<2910::aid-cncr2820711005>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobson BC, Shami VM, Faigel DO, Larghi A, Kahaleh M, Dye C, Pedrosa M, Waxman I. Through-the-scope balloon dilation for endoscopic ultrasound staging of stenosing esophageal cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:817–822. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9488-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nesje LB, Svanes K, Viste A, Laerum OD, Odegaard S. Comparison of a linear miniature ultrasound probe and a radial-scanning echoendoscope in TN staging of esophageal cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:997–1002. doi: 10.1080/003655200750023101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhutani MS, Hawes RH, Hoffman BJ. A comparison of the accuracy of echo features during endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration for diagnosis of malignant lymph node invasion. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:474–479. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]