Abstract

Background

While detailed history, physical examination, and laboratory tests are of great importance when examining a patient with diverticular disease, they are not sufficient to diagnose (or stratify) diverticulitis without cross-sectional imaging (ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT)).

Methods

Qualified US has diagnostic value equipotent to qualified CT, follows relevant legislation for radiation exposure protection, and is frequently effectual for diagnosis. Furthermore, its unsurpassed resolution allows detailed investigation down to the histological level. Subsequently, US is considered the first choice of imaging in diverticular disease. Vice versa, CT has definite indications in unclear/discrepant situations or insufficient US performance.

Results

Endoscopy is not required for the diagnosis of diverticulitis and shall not be performed in the acute attack. Colonoscopy, however, is warranted after healing of acute diverticulitis, prior to elective surgery, and in atypical cases suggesting other diagnoses. Perforation/abscess must be excluded before colonoscopy.

Conclusion

Reliable diagnosis is fundamental for surgical, interventional, and conservative treatment of the different presentations of diverticular disease. Not only complications of acute diverticulitis but also a number of differential diagnoses must be considered. For an adequate surgical strategy, correct stratification of complications is mandatory. Subsequently, in the light of currently validated diagnostic techniques, the consensus conference of the German Societies of Gastroenterology (DGVS) and of Visceral Surgery (DGAV) has passed a new classification of diverticulitis displaying the different facets of diverticular disease. This classification addresses different types (not stages) of the condition, and includes symptomatic diverticular disease (SUDD), largely resembling irritable bowel syndrome, as well as diverticular bleeding.

Key Words: Diverticulitis, Diagnosis of diverticulitis, Ultrasound in diverticulitis, Computed tomography in diverticulitis, Colonoscopy in diverticulitis

Introduction

Diverticular disease, i.e. symptoms and/or complications due to diverticulosis of the colon, ranks 5th among the most costly gastroenterological diseases in the Western world [1]. Thus, and because the risk of diverticular disease increases with age, diagnosis will remain a pertinent challenge in the future. Even more challenging are i) the recognition of differential diagnoses particularly in relation to rather uncomplicated courses (e.g. segmental colitis associated with diverticular disease (SCAD) or symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD) - the latter being probably not more than a variant of irritable bowel syndrome -, and ii) the accumulation of diagnostic information detailed enough to foster a classification that recognizes in detail any complicated course and thereby avoiding inappropriate undertreatment along with (antibiotic or surgical) overtreatment [2].

While the development of colonic diverticulosis per se is not considered a disease in itself, the condition may contribute to complications if other noxae are present, e.g. nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; including increased bleeding risk under NSAIDs and aspirin), corticosteroids, opiates, or cigarette smoking.

Definition

Colonic diverticula are an acquired sacculation/outpouching of the mucosal and submucosal layers penetrating muscular leaks in the colonic wall at the site of the mucosa-supplying arteries. Among the prerequisites (i.e. functional such as increased luminal pressure, and morphological) for the development of colonic (pseudo-)diverticula, muscular hypertrophy is a diagnostic hallmark.

Diverticulitis is characterized by an inflammatory process starting usually within the diverticulum (occlusion by a fecalith and microperforation) or at the neck of the diverticulum (ischemia or mechanical injury). Inflammation with microperforation involves a peridiverticular mesenteric inflammatory reaction which may progress to pericolic and mural phlegmonous infiltration as well as fistulization, sealed perforation, abscess, free perforation, peritonitis, and a stenosing inflammatory sigmoid tumor. Another (distinct) complication of diverticular disease is bleeding [3].

The established differentiation between complicated and uncomplicated diverticulitis relies on the presence (absence) of perforation which is diagnosed by the detection of air, fistulas, or abscesses.

The rather new term of SUDD must not be confused with uncomplicated diverticulitis because it does not rely on the criteria of diverticulitis (i.e. inflammation and imaging) but on local pain and, eventually, some inflammatory parameters (in the stool or serum) alone, thereby not distinguishing e.g. microbial infections of undetected etiology (such as SCAD) or irritable bowel symptoms from ‘true’ diverticulitis.

Smoldering diverticulitis on the other hand is a surgically coined phrase for those patients with symptomatic diverticulitis, in whom the diverticulitis remains obscure (in computed tomography (CT) scan, and sometimes also with barium enema and/or colonoscopy) until sigmoid resection is performed (histological diagnosis).

When Does Diverticulitis Occur - and What Does It Mean?

While the risk of diverticulosis and hospitalization for diverticulitis increases with age, the relative probability for developing diverticulitis decreases with age. Furthermore, the need for hospitalization and elective surgery showed highest growth rates in the younger (<45 years) population [4,5,6].

Non-elective hospitalization for ‘acute diverticulitis’ displays a remarkably stable seasonal cyclic undulation with highest incidence in the summer months [7]. Based on this pattern, it is tempting to speculate that undiagnosed ‘summer infections’ may contribute to the clinical picture, especially since recent first publications have questioned the necessity for antibiotic therapy in ‘uncomplicated diverticulitis’ [8].

The core question is whether or not uncomplicated and complicated diverticulitis are different intense expressions of the same disease or variants in a spectrum of various etiologies or pathogenetic mechanisms. The latter view is supported not only by the aforementioned cyclicity but also by the now established understanding that perforated diverticular disease usually occurs as the first manifestation and not as a complication of prior diverticulitis episodes with progressive age-dependent risk (as claimed by Parks' theory). Furthermore, subtle differentiation of e.g. mesenteric inflammatory veno-occlusive disease (MIVOD), SCAD, NSAID lesions associated with diverticular disease (vs. NSAID-complicated diverticulitis), or prolapsing mucosal folds in diverticular disease requires more attention to properly understand diverticulitis with respect to diagnostic needs and therapeutic consequences [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19].

The impact of careful differential diagnosis is underscored by the fact that approximately 80% of patients with acute diverticulitis treated at a surgical unit are discharged without operation [20,21]. Thus, one could focus the current debate on i) mild episodes at the interface between ambulant medicine and hospitalization on the one hand, and ii) episodes at the interface between conservative clinical and operative treatment on the other hand.

As it is quite clear from a radiation exposure point of view (increasingly important with the decreasing age of the affected patients) that not every patient with suspected diverticulitis can and should undergo a CT scan, it has also become evident that not every patient with a minor perforation/small abscess must be operated on. As a consequence, however, without CT scan or operation there is no classification of diverticulitis for the vast majority of patients, because the hitherto used classifications (Hansen & Stock (HS), Hinchey) are based on either CT or operative criteria.

Classification of Diverticular Disease - Now and Then

Most classifications have been modified over time because weak points became evident when new aspects in diagnosis or therapy occurred. Hinchey's classification (1978), based on that of Hughes (1963), focused on different expressions of abscess size and location. It was complemented by Sher (1997) and Wasvary (1999). The HS classification (Hansen & Stock, 1999) was used predominantly in Germany while other countries preferred Neff's classification. Siewert (1995), Ambrosetti (2002), and Tursi (2008) suggested simplified classifications while a group from the Netherlands favored a more complex and sophisticated approach (Klarenbeck, 2012) [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33].

The German guideline, recently (2014) passed by the German Societies of Gastroenterology (DGVS) and of Visceral Surgery (DGAV), unanimously agreed on another classification (Classification of Diverticular Disease (CDD)), which takes practical algorithms (symptomatic, asymptomatic, complicated, uncomplicated, acute, recurrent), ongoing surgical aspects (purulent vs. fecal peritonitis), and contemporary diagnostic standards in clinical practice into account. As a result, this classification comprises the entire spectrum of diverticular disease; however, it is not tied to a specific diagnostic preference (such as CT vs. ultrasonography (US)) and it does not refer to stages (which would indicate progressive severity with increasing stages) but rather to different types of presentation [3] (table 1).

Table 1.

Classification of diverticular disease (CDD)

| Type | Definition | Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Type 0 | asymptomatic diverticulosis | random finding; asymptomatic; not a disease per se |

| Type 1 | acute uncomplicated diverticulitis | |

| Type 1a | diverticulitis without peridiverticulitis | symptoms attributable to diverticula; signs of inflammation (laboratory tests): optional; typical cross-sectional imaging |

| Type 1b | diverticulitis with phlegmonous peridiverticulitis | signs of inflammation (laboratory tests): mandatory; cross-sectional imaging: phlegmonous diverticulitis |

| Type 2 | acute complicated diverticulitis | signs of inflammation (laboratory tests): mandatory; typical cross-sectional imaging |

| Type 2a | microabscess | concealed perforation, small abscess (≤1 cm); minimal paracolic air |

| Type 2b | macroabscess | Paracolic or mesocolic abscess (>1 cm) |

| Type 2c | free perforation | free perforation, free air/fluid; generalized peritonitis |

| Type 2c1 | purulent peritonitis | |

| Type 2c2 | fecal peritonitis | |

| Type 3 | chronic diverticular disease | relapsing or persistent symptomatic diverticular disease |

| Type 3a | symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD) | localized symptoms; laboratory test (calprotectin): optional |

| Type 3b | relapsing diverticulitis without complications | signs of inflammation (laboratory tests): present; cross-sectional imaging: indicates inflammation |

| Type 3c | relapsing diverticulitis with complications | identification of stenoses, fistulas, conglomerate tumor |

| Type 4 | diverticular bleeding | diverticula identified as the source of bleeding |

Diagnosing Diverticulitis

The diagnosis of (sigmoid) diverticulitis in a patient with left lower quadrant pain requires both, proof of an inflammatory response (C-reactive protein (CRP) > white blood cell (WBC) count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)) and localization of inflammation at the site of a diverticulum using an imaging method, i.e. US or CT [3].

According to the pathogenesis of diverticulitis, hypertrophy (and elastosis) with increasing width of the circular muscle layer is a constant trait with the diverticula developing at natural gaps associated with the penetration of arterioles supplying the (sub-)mucosal layers. Furthermore, diverticulitis starts in a single diverticulum only, which is usually the site of maximum pain under compression (although inflammation may secondarily involve further diverticula in the neighborhood, i.e. progression in longitudinal direction). Finally, inflammation usually starts in the outpouched mucosa in the diverticulum, i.e., it is endoscopically invisible unless inflammation spreads back to the mucosa from outside the wall, or a tear in the diverticular neck due to the passage (‘birth’) of a fecalith triggers diverticulitis (fig. 1a, b). Hence, the core question for cross-sectional imaging is not only whether an abscess/perforation is present or not, but also whether the aforementioned morphological criteria of diverticulitis are present or whether e.g. segmental colonic inflammation involves a diverticula-bearing segment only.

Fig. 1.

a Inflamed orifice of a diverticulum with occluding fecalith. This pattern is considered to reflect retrograde penetration of inflammation from the outpouched diverticulum. b Inflamed and torn mucosa in the orifice of an empty diverticulum. This pattern is considered to reflect the passage of a fecalith.

These considerations lend support to the view that clinical examination alone (signs and symptoms) is insufficient to diagnose diverticulitis.

A position statement by the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI) on elective resection for diverticulitis states that ‘patients should not be told that they have diverticulitis unless there is colonoscopic and/or radiological evidence of inflammation in the presence of diverticular disease’ [34]. Although there is no role for endoscopy in acute diverticulitis as long as cross-sectional imaging (US, CT) is diagnostic, this statement hints at the direction shared by the German guideline [3]: Imaging of the morphological substrate of diverticulitis (by either US or CT) is mandatory for the diagnosis of diverticulitis.

Signs of sigmoidal diverticulitis are also described by the term ‘left-sided appendicitis’ with the following symptoms: i) spontaneous pain in the left lower quadrant exaggerated by movement; ii) inflammatory reaction (CRP, WBC, temperature); and iii) local guarding upon palpation. This triad, however, is variable, time-dependent, and unspecific, and thus may raise the suspicion of diverticulitis without satisfying contemporary diagnostic requirements. Based on history and physical examination along with laboratory data, clinical judgment has a sensitivity of 65-70% only, a figure which is relatively consistent among different studies [35,36,37,38].

Therefore, a reliable diagnosis of diverticulitis requires cross-sectional imaging both in the ambulant setting and in hospital [3,39].

Differential Diagnoses

Clinically it ought to be emphasized that sigmoid diverticulitis may cause symptoms not only in the left lower quadrant but also in the right lower quadrant (elongated sigmoid loop) and anywhere in the lower abdomen. Right-sided diverticulitis even extends this spectrum towards the right upper abdomen. Thus, frequent differential diagnoses of diverticular disease/diverticulitis are inflammatory and non-inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract and the urogenital system, as well as vascular diseases (table 2).

Table 2.

Differential diagnoses of diverticular disease/diverticulitis

| Inflammatory bowel diseases |

| NSAID colitis, ischemic colitis, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, infectious enteritis/colitis, radiation colitis, neutropenic colitis, appendicitis, appendicitis epiploica (appagaditis), Meckel's diverticulitis |

| Non-inflammatory bowel diseases |

| Irritable bowel disease, intussusception, colorectal carcinoma, hernia, adhesions, volvulus, gut wall hematoma, foreign bodies |

| Urogenital diseases |

| Ureterolithiasis, nephrolithiasis, cystitis, ureterocele, vesiculitis seminalis, prostatitis, adnexitis/salpingitis, endometriosis, uterine neoplasia, ovarian torsion, tumor, cyst (± rupture), ectopic gravidity, varicosis of the ovarian vein |

| Others |

| Vascular disease (aneurysma/dissection, thrombosis, inflammation (vasculitis), abdominal wall and retroperitoneal processes (hematoma, abscess) |

Differential diagnosis is especially difficult when the differentiation between irritable bowel disease and SUDD is addressed. While the latter does not have a morphological substrate on CT or US, and serological inflammatory responses are also normal, slightly elevated fecal calprotectin concentrations may occur [3]. Vice versa, the ‘closed eye sign’ may serve as a weak indicator for irritable bowel syndrome; however, there is a good deal of overlap and hence diagnostic uncertainty between these two ‘entities’. Lastly, an episode of acute diverticulitis may serve as a trigger for irritable bowel syndrome (odds ratio 4.7) [40,41].

In the case of SCAD, a diagnosis cannot be established without a positive stool culture, positive viral proof, or colonoscopy showing segmental erythema between (non-inflamed) diverticula (fig. 2). As these tools are not routinely applied in patients with pain in the left lower quadrant, this diagnosis may be more relevant than hitherto assumed, particularly during summer. Identification of such a subgroup might be especially rewarding in view of current attempts to avoid antibiotic therapy in patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis, and surgical intervention would undoubtedly constitute overtreatment.

Fig. 2.

a Scarcely detectable microbleeding next to the orifice of a diverticulum and increased injection of the mucosal vessels as signs of microbial infection (SCAD), here due to Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC). b Piece of a blister pack cutting into a diverticulum which already bears the residues of a previous blister pack extraction on the day before (in a patient who swallowed part of his medication together with some of the blister pack).

Colorectal carcinoma is not associated with diverticulitis, but some risk factors and the age at risk overlap. Therefore, after an episode of acute diverticulitis, colonoscopy is warranted in patients >50 years who have not undergone endoscopy before [3].

Diagnostic Steps

Clinical examination for diverticulitis comprises abdominal palpation, percussion and auscultation, examination of the inguinal rings, rectal examination, taking the temperature, urinalysis, and laboratory tests (with emphasis on CRP, WBC count, and ESR). Shifts in laboratory parameters may be delayed; therefore retesting after 2 days (‘48-h rule’) is prudent and improves safety for the benefit of the patient [3,42,43].

As already pointed out, imaging methods (US, CT) are deemed mandatory in addition to history taking and physical examination for an exact diagnosis, classification, and differential diagnosis. In contrast, there is currently no role for routine magnetic resonance imaging [3].

Because in Germany legal radiation protection applies according to § 23(1) of the German Radiation Control Regulation (Röntgenverordnung (RöV)) from 2011, radiology is only allowed ‘… if a justified indication applies. For such a balanced consideration other techniques with equivalent health benefit, which do not bear radiation hazards, must be taken into account’.

Thus, long in the shade of CT, it is time for US to take center stage for the following reasons: i) a meta-analysis certified ‘the best evidence for diagnosis of diverticulitis in the literature is on ultrasonography; only one small study of good quality was found on CT or MRI colonoscopy’[44]; ii) US is applicable in all patients with suspected diverticulitis (e.g. outpatients and emergency cases); iii) it is cheap; iv) in addition to a reliable initial diagnosis, it allows close follow-up; and v) last but not least, it has higher resolution power than a CT scan.

Ultrasonography - Why, How, Who, and Who not?

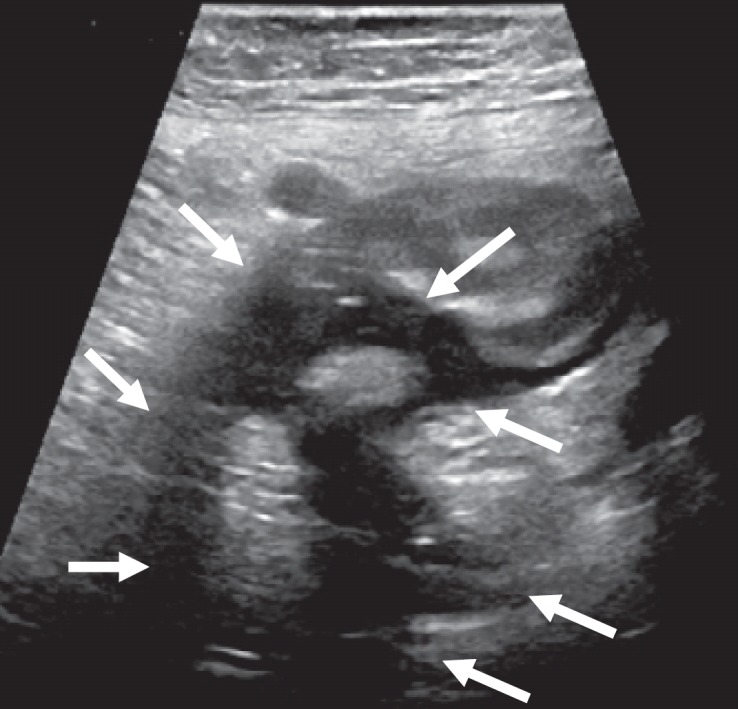

US is applied directly at the point of pain and guarding, which usually reveals the inflamed diverticulum and/or associated complications (fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 3.

Sonographic findings in a patient with diverticulitis. a Well-defined, broad mucosal layer of the outpouched diverticulum surrounded by an echo-rich mesenteric reaction (arrows) representing ‘The diverticulum with different echogenicity in the centre of a pericolonic fatty tissue reaction’ (Hollerweger [46]). The orifice and neck of the diverticulum are indicated by the dotted arrow. b Circle pointing to discrete air bubbles in the mesenteric fat defining a type 2a acute diverticulitis (which is not recognized in fig. 3a representing type 1a). Stars indicate broadened colonic wall diameter and some inflammatory swelling of the mucosa at the orifice of the diverticulum.

The inflamed diverticulum may or may not contain an echo-rich and more or less crescent-shaped fecalith (see also fig. 1a, b), but once extruded, spontaneous drainage of pus into the colon is hypothesized to decrease pressure and the risk for perforation (fig. 4a, b) [45].

Fig. 4.

a Semilunar appearance of a fecalith (echogenic) within the broadened (echo-poor) mucosa of the diverticulum, surrounded by the echogenic mesenteric reaction (‘mesenteric cap’). Note also the muscular hypertrophy which is a prerequisite for the formation of diverticula; however, here it is not a sign of diverticulitis. b Acute diverticulitis with an empty inflamed diverticulum (echo-poor), surrounded by the echogenic mesenteric reaction (‘dome sign’). Note the strong inflammatory infiltration of the colonic wall segment (phlegmon) next to the diverticulitis in contrast to muscular hypertrophy (11:30-14:30 clockwise orientation).

The core US finding of diverticulitis (figs. 3, 4) is ‘The diverticulum with different echogenicity in the centre of a pericolonic fatty tissue reaction’ (Hollerweger [46]), i.e. surrounded by an echogenic mesenteric cap, in conjunction with i) hypoechoic and initially asymmetrical wall thickening (>5 mm) with loss of wall layering, reduced wall compliance under pressure, and narrowing of the lumen, and ii) occasionally hypoechoic ‘inflammation lanes’ which are considered inflammatory exsudation (fig. 4b at 10:30 clockwise orientation).

Microperforations, fistulas, and abscesses are characterized by air bubbles in the mesenterium, in a hypoechoic lane, or in an echo-poor fluid retention, while free peritoneal air or air bubbles in the retroperitoneal space indicate free or retroperitoneal perforation.

In experienced hands, sensitivity and specificity of US are 98% [38]. In uncomplicated diverticulitis, direct visualization of the inflamed diverticulum amounts to 96%; however, it is more difficult if complications dominate (77%, specificity 99%) [46].

Deep abscesses, mesenteric air, and retroperitoneal perforation are the most difficult triad for US in this scenario, and the examiner should especially consider this if US produces an ‘unsatisfactory picture’ which is in contrast with an obviously ‘ill’ patient. This then becomes a case for CT; however, detection of diverticula or diverticular inflammation at CT has only insufficient sensitivity (30%) and interobserver agreement (despite an overall 99% sensitivity and specificity) [47,48].

A comparative study with four experienced US examiners and CT scans performed at university level resulted in 100% sensitivity for US (vs. CT 98%) with 97% specificity for both procedures. Advanced peridiverticulitis and sealed perforations were overestimated by CT and rather underestimated at US, but free perforations and abscesses were missed by neither of the two techniques [49].

Often, it is argued that the outcome of US depends on the equipment and on the examiner. However, currently sold US devices, preferably with a ≥5 MHz probe, all meet the required standards and thus are throughout fully adequate for the diagnosis of diverticulitis and its differential diagnoses. With respect to the examiner, it must be clear that no medical technique - be it electrocardiogram, stethoscope, or CT - can ever be valid if the examiner is not familiar with it. Adequate training in US for diverticulitis with production of valid results can be assumed after approximately 500 (targeted) US examinations [50]. US trainees with <500 examinations targeted to diseases of the gut should not issue US reports on diverticulitis on their own authority.

Computed Tomography - How, When, Why?

For the diagnosis of diverticulitis, abdominal CT scans are regularly performed with intravenous and oral contrast in the portal venous phase. Complementary rectal filling is recommended to provide better contrast at the rectosigmoid segment. Especially in obese patients, CT scans can at first also be performed satisfactorily without any contrast.

CT is a long-established and, at least from the surgeon's perspective, valid technique for imaging acute diverticulitis and assessing its severity (complications) and differential diagnoses, thereby guiding e.g. the surgical strategy [21,51]. Radiation exposure, however, precludes its use in all patients suspected to have an acute episode of diverticulitis.

In contrast to US, the key CT criteria do not include the inflamed diverticulum itself (which is detected in approximately 30% only), but rather perifocal ‘stranding’ (mesenteric inflammation), detection of free fluid, and a broadened colonic wall diameter of >(3-)5 mm [47].

A cornerstone study by Ambrosetti et al. [31] showed that age, abscess, and air are the triple-A clue to guide prognosis and surgical management. In detail, patients with severe CT findings (i.e. an abscess (median diameter ≥ 3 cm) or extracolonic air/contrast medium) had significantly more complications during their follow-up (36 vs. 17%) after conservative treatment of their first episode. Vice versa, it is noteworthy that two-thirds of patients with severe CT findings did not have such complications.

Currently, new publications may cast doubt on the unanimous faith in CT scans for acute diverticulitis. In patients operated on for perforation, accuracy of CT was found to be 71-92% (positive predictive value (PPV) 45-89%) in different stages. In 42% of patients at Hinchey stage III, CT led to understaging (Hinchey I and II), resulting in a PPV of CT of 61% in Hinchey stages I and II only [52].

Another comparison of preoperative CT findings with both the situs and the histology at surgery showed correct staging by CT at HS IIa in 52% (operation) and 56% (histology). For this stage, understaging occurred in 12 (11)%, overstaging in 36 (33)%. In this study, validity for stages with an abscess (HS IIb, Hinchey I and II) was much better (operation 92%, histology 90%), and free perforation (HS IIc, Hinchey III and IV) was detected in 100% resulting in a PPV for CT in HS IIa, HS IIb, and HS IIc of 52 (56)%, 92 (90)%, and 100%, respectively [27,53].

Such sizeable understaging (42%) in perforating diverticulitis [52] and overstaging (1/3) in phlegmonous diverticulitis [53] demonstrates that CT was probably the best technique available in the past but that it may be hard to accept it as gold standard. Nevertheless, in comparison with US, CT has definite advantages in the detection of distant mesenteric and pelvic abscesses.

Colonoscopy - When and Why?

Colonoscopy is the diagnostic (and therapeutic) method of choice in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding and thus also in diverticular bleeding.

The current guideline [3], however, advises against the use of colonoscopy for diagnosing acute diverticulitis because it is i) inadequate and ii) potentially dangerous (increasing the risk or intensity of perforation). Figure 5 shows an abscess in such a patient who underwent colonoscopy during an episode of acute diverticulitis (in another hospital) and complained of more severe pain thereafter. This in conjunction with recovery failure prompted her family doctor to admit her for surgery.

Fig. 5.

Abscess (type 2b) after colonoscopy in acute sigmoid diverticulitis (arrows).

In uncharacteristic cases, however, colonoscopy might be useful or mandatory after exclusion of perforation, because otherwise differential diagnoses such as SCAD, NSAID-induced lesions, ischemic colitis, right-sided diverticulitis, or foreign body-induced diverticular injury (fig. 2a, b) might not be detected or adequately assessed. In this scenario and gently performed by an experienced examiner, colonoscopy is regarded a safe procedure by most authorities [3] (see also the Interdisciplinary Discussion on this topic in this journal). It is noteworthy that inflammation at the orifice of diverticula is observed in approximately 0.8% of colonoscopies without evidence of diverticulitis [54].

After an episode of acute diverticulitis, colonoscopy is recommended in patients who are >50 years of age and who have not had a colonoscopy before, and also in patients who are scheduled to undergo surgery for diverticular disease. In these cases, a safety interval between acute diverticulitis and colonoscopy of 6 weeks appears advisable.

Algorithm for Diagnosing Diverticulitis

The above reassessed facts, considerations, and points of view form the basis for a summarizing diagnostic algorithm shown in figure 6, which allows tailored adaptation to the different prevailing clinical situations and facilities [3].

Fig. 6.

Diagnostic algorithm for suspected diverticulitis.

Disclosure Statement

The author has no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1500–1511. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Detry R, Jamez J, Kartheuser A, et al. Acute localized diverticulitis: optimum management requires accurate staging. Int J Colorect Dis. 1992;7:38–42. doi: 10.1007/BF01647660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leifeld L, Germer CT, Böhm S, et al. S2k-Leitlinie Divertikelkrankheit/Divertikulitis. S2k Guidelines Diverticular Disease/Diverticulitis. Z Gastroenterol. 2014;52:663–710. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1366692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strate LL, Modi R, Cohen E, Spiegel BM. Diverticular disease as a chronic illness: evolving epidemiologic and clinical insights. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1486–1493. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahedi K, Fuller G, Bolus R, et al. Long-term risk of acute diverticulitis among patients with incidental diverticulosis found during colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1609–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Etzioni DA, Mack TM, Beart RW, Kaiser AM. Diverticulitis in the United States: 1998-2005. Changing patterns of disease and treatment. Ann Surg. 2009;249:210–217. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181952888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ricciardi R, Roberts PL, Read TE, et al. Cyclical increase in diverticulitis during the summer months. Arch Surg. 2011;146:319–323. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chabok A, Pâhlman L, Hjern F, et al. AVOD Study Group Randomized clinical trial of antibiotics in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2012;99:532–539. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janes S, Meagher A, Frizelle FA. Elective surgery after acute diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2005;92:133–142. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander J, Karl RC, Skinner DB. Results of changing trends in the surgical management of complications of diverticular disease. Surgery. 1983;94:683–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapman J, Davies M, Wolff B. Complicated diverticulitis: is it time to rethink the rules? Ann Surg. 2005;242:576–583. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000184843.89836.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Somasekar K, Foster ME, Haray PN. The natural history of diverticular disease: is there a role for elective colectomy? J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2002;47:481–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parks TG. Natural history of diverticular disease of the colon. A review of 521 cases. Br Med J. 1969;4:639–645. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5684.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parks TG, Connell AM. The outcome in 455 patients admitted for treatment of diverticular disease of the colon. Br J Surg. 1970;57:775–778. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800571021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imperiali G, Terpin MM, Meucci G, et al. Segmental colitis associated with diverticula: a 7-year follow-up study. Endoscopy. 2006;38:610–612. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flaherty MJ, Lie JT, Haggitt RC. Mesenteric inflammatory veno-occlusive disease. A seldom recognized cause of intestinal ischemia. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:779–784. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199408000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludeman L, Shepherd NA. What is diverticular colitis? Pathology. 2002;34:568–572. doi: 10.1080/0031302021000035974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly JK. Polypoid prolapsing mucosal folds in diverticular disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:871–878. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199109000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tendler DA, Aboudola S, Zacks JF, et al. Prolapsing mucosal polyps: an underrecognized form of colonic polyp - a clinicopathological study of 15 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:370–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anaya DA, Flum DR. Risk of emergency colectomy and colostomy in patients with diverticular disease. Arch Surg. 2005;140:681–685. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.7.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaikh S, Krukowski ZH. Outcome of a conservative policy for managing acute sigmoid diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2007;94:876–879. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinchey EJ, Schaal PG, Richards GK. Treatment of perforated diverticular disease of the colon. Adv Surg. 1978;12:85–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes ES, Cuthbertson AM, Carden AB. The surgical management of acute diverticulitis. Med J Aust. 1963;50:780–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sher ME, Agachan F, Bortul M, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for diverticulitis. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:264–267. doi: 10.1007/s004649900340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wasvary H, Turfah F, Kadro O, et al. Same hospitalization resection for acute diverticulitis. Am Surg. 1999;65:632–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohler L, Sauerland S, Neugebauer E. Diagnosis and treatment of diverticular disease: results of a consensus development conference. The Scientific Committee of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:430–436. doi: 10.1007/s004649901007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansen O, Stock W. Prophylaktische Operation bei der Divertikelkrankheit des Kolons - Stufenkonzept durch exakte Stadieneinteilung. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 1999;(suppl 2):1257–1260. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neff CC, van Sonnenberg E. CT of diverticulitis: diagnosis and treatment. Radiol Clin North Am. 1989;27:743–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mora Lopez L, Serra Pla S, Serra-Aracil X, et al. Application of a modified Neff classification to patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:1442–1447. doi: 10.1111/codi.12449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siewert JR, Huber FT, Brune IB. Early elective surgery of acute diverticulitis of the colon. Chirurg. 1995;66:1182–1189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ambrosetti P, Becker C, Terrier F. Colonic diverticulitis: impact of imaging on surgical management - a prospective study of 542 patients. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:1145–1149. doi: 10.1007/s00330-001-1143-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Giorgetti G, et al. The clinical picture of uncomplicated versus complicated diverticulitis of the colon. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2474–2479. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klarenbeek BR, de Korte N, van der Peet DL, Cuesta MA. Review of current classifications for diverticular disease and a translation into clinical practice. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:207–214. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1314-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fozard JBJ, Armitage NC, Schofieldt JB, Jones OM. ACPGBI position statement on elective resection for diverticulitis. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13(suppl 3):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toorenvliet BR, Bakker RFR, Breslau PJ, et al. Colonic diverticulitis: a prospective analysis of diagnostic accuracy and clinical decision-making. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:179–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laméris W, van Randen A, van Gulik TM, et al. A clinical decision rule to establish the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis at the emergency department. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:896–904. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181d98d86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laurell A, Hansson L-E, Gunnarsson U. Acute diverticulitis - clinical presentation and differential diagnostics. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:496–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.01162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwerk WB, Schwarz S, Rothmund M. Sonography in acute colonic diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:1077–1084. doi: 10.1007/BF02252999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Connor ES, Smith MA, Heise CP. Outpatient diverticulitis: mild or myth? J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1389–1396. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1861-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gray DWR, Dixon JM, Collin J. The closed eye sign: an aid to diagnosing non-specific abdominal pain. BMJ. 1988;297:837. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6652.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen E, Fuller G, Bolus R, et al. Increased risk for irritable bowel syndrome after acute diverticulitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1614–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evans J, Kozol R, Frederick W, et al. Does a 48-hour rule predict outcomes in patients with acute sigmoid diverticulitis? J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:577–582. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0405-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Von Rahden BHA, Kircher S, Landmann D, et al. Glucocorticoid induced TNF receptor (GITR) expression: potential molecular link between steroid intake and complicated diverticulitis? Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:1276–1286. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.02967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liljegren G, Chabok A, Wickbom M, et al. Acute colonic diverticulitis: a systematic review of diagnostic accuracy. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:480–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Puylaert JB. Ultrasound of colon diverticulitis. Dig Dis. 2012;30:56–59. doi: 10.1159/000336620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hollerweger A, Macheiner P, Rettenbacher T, et al. Colonic diverticulitis: diagnostic value and appearance of inflamed diverticula - sonographic evaluation. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:1956–1963. doi: 10.1007/s003300100942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kircher MF, Rhea JT, Kihiczak D, Novelline RA. Frequency, sensitivity, and specificity of individual signs of diverticulitis on thin-section helical CT with colonic contrast material: experience with 312 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:1313–1318. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.6.1781313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tack D, Bohy P, Perlot I, et al. Suspected acute colon diverticulitis: imaging with low-dose unenhanced multi-detector row CT. Radiology. 2005;237:189–196. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2371041432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Farag Soliman M, Wüstner M, Sturm J, et al. Primärdiagnostik der akuten Sigmadivertikulitis. Sonographie versus Computertomographie, eine prospektive Studie. Ultraschall in Med. 2004;25:342–347. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-813381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Randen A, Laméris W, van Es HW, et al. on behalf of the OPTIMA study group A comparison of the accuracy of ultrasound and computed tomography in common diagnoses causing acute abdominal pain. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:1535–1545. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2087-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ambrosetti P, Grossholz M, Becker C, et al. Computed tomography in acute left colonic diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 1997;84:532–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1997.02576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gielens MPM, Mulder IM, van der Harst E, et al. Preoperative staging of perforated diverticulitis by computed tomography scanning. Tech Coloproctol. 2012;16:363–368. doi: 10.1007/s10151-012-0853-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ritz JP, Lehmann KS, Loddenkemper C, et al. Preoperative CT staging in sigmoid diverticulitis - does it correlate with intraoperative and histological findings? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2010;395:1009–1015. doi: 10.1007/s00423-010-0609-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ghorai S, Ulbright TM, Rex DK. Endoscopic findings of diverticular inflammation in colonoscopy patients without clinical acute diverticulitis: prevalence and endoscopic spectrum. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:802–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]