Abstract

Study Design:

Fractures of the atlas are classified based on the fracture location and associated ligamentous injury. Among patients with atlas fractures treated using external immobilization, nonunion of the fracture could be seen.

Objective:

Ideally, treatment strategy for an unstable atlas fracture would involve limited fixation to maintain the fracture fragments in a reduced position without restricting the range of motion (ROM) of the atlantoaxial and atlantooccipital joints.

Summary of Background Data:

Such a result can be established using either transoral limited internal fixation or limited posterior lateral mass fixation. However, due to high infection risk and technical difficulty, posterior approaches are preferred but none of these techniques can fully address anterior 1/4 atlas fractures such as in this case.

Materials and Methods:

A novel open and direct technique in which a unilateral lag screw was placed to reduce and stabilize a progressively widening isolated right-sided anterior 1/4 single fracture of C1 that was initially treated with a rigid cervical collar is described.

Results:

Radiological studies made after the surgery showed no implant failure, good cervical alignment, and good reduction with fusion of C1.

Conclusions:

It is suggested that isolated C1 fractures can be surgically reduced and immobilized using a lateral compression screw to allow union and maintain both C1-0 and C1-2 motions, and in our knowledge this is the first description of the use of a lag screw to achieve reduction of distracted anterior 1/4 fracture fragments of the C1 from a posterior approach. This technique has the potential to become a valuable adjunct to the surgeon's armamentarium, in our opinion, only for fractures with distracted or comminuted fragments whose alignment would not be expected to significantly change with classical lateral mass screw reduction.

Keywords: Atlas, fracture, lag screw, nonfusion, screw, unilateral

INTRODUCTION

Fractures of the atlas constitute 25% of all craniocervical injuries, 2-13% of all cervical spine injuries, and approximately 1.3% of all spinal fractures.[1,2] They were originally described in the 1800s and further characterized through classifications by Jefferson,[3] Segal et al.[4] and finally Levine and Edwards,[5] based on the fracture location and associated ligamentous injury.[6] The most common subtypes are burst fractures, posterior arch fractures, and comminuted lateral mass fractures, each with a prevalence of 20-30% of all atlas injuries.[7]

Among patients with atlas fractures treated using external immobilization, nonunion of the fracture could be seen and neck pain was present in 20-80% of the patients.[4] Ideally, treatment strategy for an unstable atlas fracture would involve limited internal immobilization to maintain the fracture fragments in a reduced position without restricting the range of motion (ROM) of the atlantoaxial and atlantooccipital joints. Such a result can be established using either transoral limited internal fixation or limited posterior lateral mass fixation.[4,7,8,9,10] However, due to high infection risk as high as 9-22%[11,12,13,14,15,16] and technical difficulty, which increases the postoperative complication rate to as high as 75%,[17] posterior approaches are preferred although there is still a risk of venous plexus and C2 nerve root injury during exposure of the C1 lateral mass.[18,19] The indications for limited posterior lateral mass fixation include fresh isolated atlas posterior 3/4 Jefferson fracture and semi-ring Jefferson fractures[9,20,21,22,23] associated with C1 lateral mass, either together with type II transverse ligament injury or that do not heal after external immobilization for 3 months.[24] Isolated atlas fractures combined with type I ligament injury may have atlantoaxial or atlantooccipital joint instability, and should be treated with C1-C2 or C0-C2 fusion.[25] However, none of these posterior approach techniques can fully address isolated anterior 1/4 atlas fractures such as in our case.

The regions of the anterior and posterior arches that connect with the lateral masses are relatively thin and represent the weakest points of the atlas, therefore being highly probable locations for fracture.[3] Due to its unique anatomy, the atlas most commonly fractures with two or more breaks in the ring structure to our knowledge; only 14 cases of an isolated fracture of the atlas detected by CT have been reported in the English literature.[16] The thin lamina causes displacement of the lateral masses and transverse atlantal ligament is insufficient to reduce the fractured parts in the anterior isolated fractures of the atlas, thus causing prolonged nonunion with neck pain such as in our case. The purpose of this paper is to describe a novel open and direct technique in which a unilateral lag screw was placed to reduce and stabilize a progressively widening isolated right-sided anterior 1/4 fracture of C1 that was initially treated with a rigid cervical collar.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

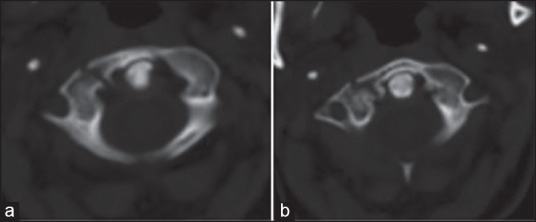

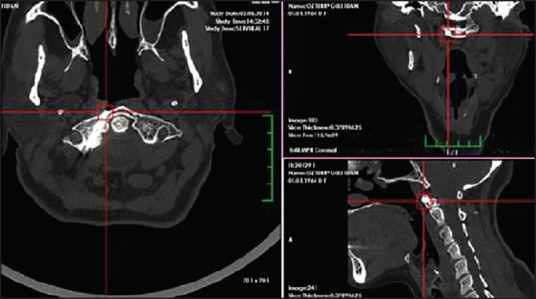

A 50-year-old woman involved in a motor vehicle accident was admitted to our department with complaints of retrograde amnesia, and neck pain and stiffness. Her neurological examination was normal except for diffuse posterior cervical spine tenderness to direct palpation. Upper cervical computed tomography (CT) revealed an isolated unilateral (right side) fracture of C1 anterior 1/4 arch with extension of the fracture to the right lateral mass. There was also mild distraction of the fracture either due to the rupture of transverse atlantal ligament or due to the biconcave structure of C1 lateral masses. Given the initial presentation and imaging results that were not suspicious for instability, it was elected to treat the patient conservatively with a rigid cervical collar and routine activity restriction. On the follow-up, even months after the trauma, she had persistent and progressively worsening neck pain both with and without the use of the rigid collar. She did not exhibit any neurological deficit or pathological reflex but reported a significant difficulty in tolerating the continuous use of the rigid cervical collar. Repeat CT imaging revealed progressive widening and distraction of the right C1 arc fracture without any callus formation [Figure 1]. Dynamic studies could not be performed due to extreme pain reported by the patient during the necessary movements. After a discussion regarding the patient's admitted noncompliance with the instructions about the use of rigid cervical collar and progression of pain together with the risks, benefits, and expectations of surgical intervention, the patient agreed to go forward with surgery. The patient was informed that data concerning the case would be submitted for publication and agreed to this.

Figure 1.

(a and b) Axial view of computed tomographic scan through the atlas demonstrating a right anterior 1/4 isolated fracture with mild distraction (the fracture line goes through the right anterior part of lateral mass)

Surgical technique

Intraoperative somatosensory-evoked potentials were used for monitoring the patient. Under general anesthesia, the patient was placed in a prone position with a Mayfield headholder (Integra Co, Plainsboro, New Jersey, USA) to keep the neck slightly flexed. A standard, midline posterior approach to the upper cervical spine was employed, with specific care taken to sweep the paraspinal musculature, fascia, and ligaments along the midline to reveal the spinous process of C2 and posterior tubercle of C1. We did not use our navigation system or intraoperative three-dimensional (3D) imaging facilities for this case. Subsequently, the junction of the lower edge of C1 posterior arch and lateral mass was exposed by subperiosteal dissection. The vertebral artery (VA) was dissected superiorly and gently retracted to expose the upper edge of the posterior vertebral arch and lateral mass of C1 on the right side only. During the operation, C1-C2 venous plexus was dissected inferiorly to be protected with cottonoids, and epidural venous bleeding controlled with bipolar cautery and gelfoam. Subperiosteal dissection was performed using Penfield dissector (Aesculap AG, Tuttlingen, Germany) were used to avoid neurovascular injury and to probe the medial wall and posterior wall of the posterior arch and the border of the lateral mass. Once the fracture line was adequately visualized, a dissector was placed and its location at the C1 posterior arch was confirmed via two-dimensional (2D) fluoroscopy.

Since the drill could slip and hurt the VA or break the C1 posterior arch during the process of forming the pilot hole, a high-speed burr was used to remove the outer narrow bone of the C1 posterior arch at the VA groove along the direction of the trajectory. The pilot hole was drilled at a point just inferior to the VA and C1 spinal nerve, at the lateral border of the C1 lateral mass, toward the right C1 lateral mass and found to be without breach on further probing. According to preoperative CT scans and intraoperative anatomy, a K-Wire (Aesculap AG, Tuttlingen, Germany) was then placed, and 2D fluoroscopy demonstrated bicortical placement. The wall of the pedicle was carefully probed to confirm the correct trajectory. For the insertion of the screw, the optimal direction of the trajectory was planned according to preoperative CT scans. The trajectory was approximately 15-20° in the medial direction and 20° in the cephalad direction. A cannulated 4 × 30 mm-sized titanium compression screw (Acutrak®, Acumed Inc. Hillsboro, Oregon, USA) was placed over the K-wire and partially advanced. The wire was then removed and the screw advanced fully with excellent purchase through the fracture line. The screw was tightened until the proximal end was countersunk into the bone for 1-2 mm. The fascial and subcutaneous layers were approximated with interrupted sutures, and the skin incision was closed with staples.

Postoperative course

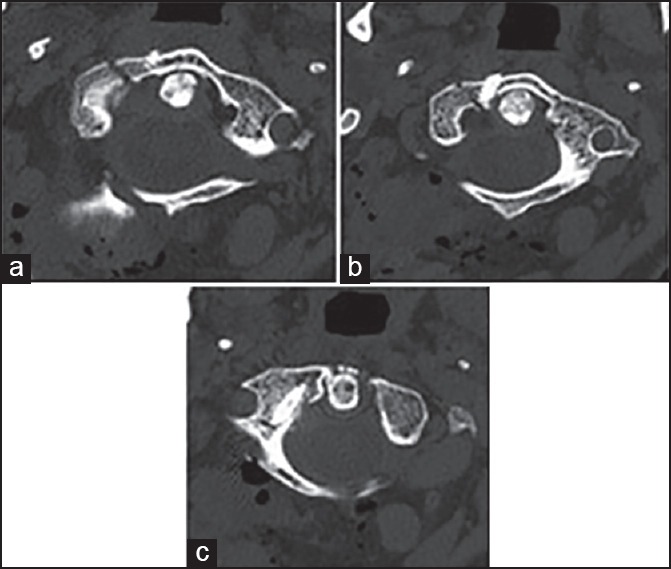

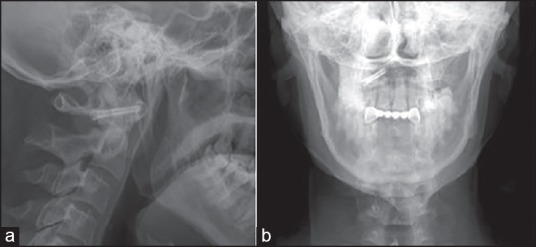

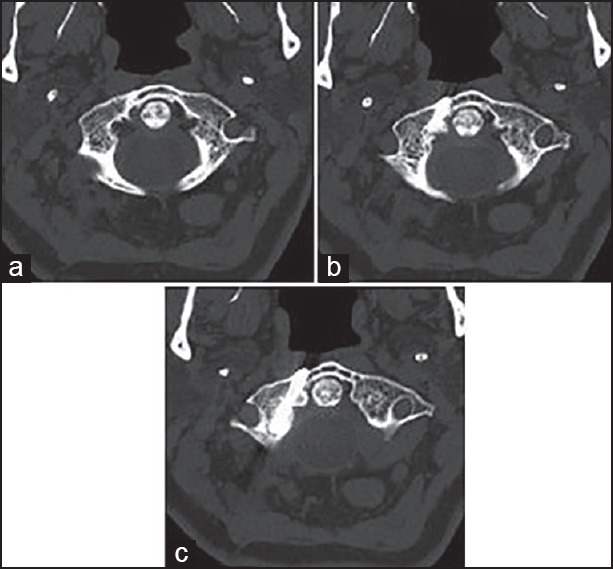

Immediately after the surgery, she reported total disappearance of the symptoms and was discharged on postoperative day 1. She started to work after the first week. Clinically, the ROM of her cervical spine was not restricted in any direction. A CT scan obtained in the early postoperative period [Figure 2] showed significant reduction of the fracture with appropriate placement of the lag screw and beginning of callus formation while x-rays [Figure 3] and CT scan taken in the late postoperative period [Figures 4 and 5] showed no implant failure, good cervical alignment, and good reduction with fusion of C1.

Figure 2.

(a-c) Axial view of noncontrast computed tomographic scan taken in the early postoperative period showing C1 reduction with the lag screw crossing the fracture line

Figure 3.

(a and b) The postoperative lateral and open-mouth radiographs at the late follow-up, revealing no implant failure, good cervical alignment, and good reduction with well-positioned screw placement in the C1

Figure 4.

(a-c) Axial view of computed tomographic scan obtained in the late follow-up period up through the atlas demonstrating good bony fusion and good reduction with well-positioned screw placement in the right anterior 1/2 single fracture line that also goes through the right anterior part of lateral mass

Figure 5.

3-dimensional reformatted CT images of the late follow-up images in the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes from thin-section CT scan, demonstrating good reduction with well-positioned screw placement through the right anterior 1/2 single fracture line

DISCUSSION

Although there are many complications with prolonged nonoperative management including pin-site infection, pin loosening, recurrent subluxation, and high nonunion rate,[26,27] many authors recommend that the rigid collar be used first[12,26] followed by head-halter traction for 3-4 weeks[28,29] in isolated atlas fractures and radiographic outcomes seem to have a high success rate[29] but neck pain is present in 20-80% of the patients after the external immobilization.[4] If the reduction cannot be maintained by these methods due to transverse atlantal ligament disruption, inadequate fracture reduction, or absence of adequate cervical immobilization,[30] surgery should be performed.[26,27] Fusion of the upper cervical spine via dorsal wiring of C1-2 was first described by Mixter and Osgood in 1910[31] and technological improvements in instrumentation over the past 30 years have allowed a significant expansion of available options for surgical fixation of this region. However, the major disadvantage of fusion is sacrifice of the normal ROM in the C1-C2 or C0-C2 joints such as C1 - C2 rotation and C0 - C1 flexion/extension.[32] In addition, an increased incidence of degeneration of the subaxial cervical spine has also been reported.[33]

Anterior 1/4, posterior 1/4, or posterior 1/4, simple C1 fractures without transverse atlantal ligament rupture assessed by MRI can be considered as stable fractures[32] while late squeal from malunion are reported.[1,7,34] As a motion-preserving technique, the single lag-screw technique is commonly used in anterior odontoid screw fixation to bring fracture fragments into better apposition.[21] The current report suggests that isolated C1 fractures can be surgically reduced and immobilized using a lateral compression screw to allow union and maintain both C1-0 and C1-2 motion, and in our knowledge this is the first description of the use of a lag screw to achieve reduction of distracted anterior 1/4 fracture fragments of the C1 from a posterior approach. This technique has the potential to become a valuable adjunct to the surgeon's armamentarium, in our opinion, only for fractures with distracted (but not comminuted) fragments, the alignment of which would not be expected to significantly change with classical lateral mass screw reduction along the trajectory of the routinely accessible posterior entry points.

A computer navigation system with intraoperative 3D imaging facilities will be of benefit for safe placement of the C1 screw if a percutaneous technique is to be used for this type of nonfusion surgery. However, for a free-hand technique, the starting point was at the undersurface junction of the C1 posterior arch and lateral mass[35] avoiding traction or irritation of the C2 nerve root,[36,37] the vulnerable venous plexus,[38,39,40] and the VA stretching superiorly on the posterior arch groove, which may sometimes be difficult to find due to the variation ponticulus posticus, an ossification arch surrounding the dorsal course of the VA on the C1 posterior arch.[41,42]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.An HS. Cervical spine trauma. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:2713–29. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199812150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickman CA, Sonntag VK. Injuries involving the transverse atlantal ligament: Classification and treatment guidelines based upon experience with 39 injuries. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:886–7. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199704000-00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jefferson G. Fractures of the atlas vertebra. Report of four cases, and a review of those previously recorded. Br J Surg. 1919;7:407–22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Segal LS, Grimm JO, Stauffer ES. Non-union of fractures of the atlas. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:1423–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine AM, Edwards CC. Traumatic lesions of the occipitoatlantoaxial complex. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989:53–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landells CD, van Peteghem PK. Fractures of the atlas: Classification, treatment and morbidity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1988;13:450–2. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198805000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bransford R, Chapman JR, Bellabarba C. Primary internal fixation of unilateral C1 lateral mass sagittal split fractures: A series of 3 cases. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2011;24:157–63. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3181e12419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung SK, Park JT, Lim J, Park J. Open posterior reduction and stabilization of a C1 burst fracture using mono-axial screws. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:E301–6. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31820644cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jo KW, Park IS, Hong JT. Motion-preserving reduction and fixation of C1 Jefferson fracture using a C1 lateral mass screw construct. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:695–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li L, Teng H, Pan J, Qian L, Zeng C, Sun G, et al. Direct posterior c1 lateral mass screws compression reduction and osteosynthesis in the treatment of unstable Jefferson fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:E1046–51. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181fef78c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ai F, Yin Q, Wang Z, Xia H, Chang Y, Wu Z, et al. Applied anatomy of transoral atlantoaxial reduction plate internal fixation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:128–32. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000195159.04197.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Holou WN, Park P, Wang AC, Than KD, Marentette LJ. Modified trans-oral approach with an inferiorly based flap. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;17:464–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu Y, Yang S, Xie H, He X, Xu R, Ma W, et al. The anatomic study on replacement of artificial atlanto-odontoid joint through transoral approach. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2008;28:327–32. doi: 10.1007/s11596-008-0322-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu Y, Albert TJ, Kepler CK, Ma WH, Yuan ZS, Dong WX. Unstable Jefferson fractures: Results of transoral osteosynthesis. Indian J Orthop. 2014;48:145–51. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.128750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kingdom TT, Nockels RP, Kaplan MJ. Transoral-transpharyngeal approach to the craniocervical junction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;113:393–400. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989570074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma W, Xu N, Hu Y, Li G, Zhao L, Sun S, et al. Unstable atlas fracture treatment by anterior plate C1-ring osteosynthesis using a transoral approach. Eur Spine J. 2013;22:2232–9. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2870-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones DC, Hayter JP. The superiorly based pharyngeal flap: A modification of the transoral approach to the upper cervical spine. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;35:368–9. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(97)90412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan J, Li L, Qian L, Tan J, Sun G, Li X. C1 lateral mass screw insertion with protection of C1-C2 venous sinus: Technical note and review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:E1133–6. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e215ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel AJ, Gressot LV, Boatey J, Hwang SW, Brayton A, Jea A. Routine sectioning of the C2 nerve root and ganglion for C1 lateral mass screw placement in children: Surgical and functional outcomes. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29:93–7. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1899-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu Y, Xu RM, Albert TJ, Vaccoro AR, Zhao HY, Ma WH, et al. Function-preserving reduction and fixation of unstable Jefferson fractures using a C1 posterior limited construct. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2014;27:E219–25. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31829a36c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin JM, Hipp JA, Reitman CA. C1 lateral mass screw placement via the posterior arch: A technique comparison and anatomic analysis. Spine J. 2013;13:1549–55. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabbosha M, Dowdy J, Pait TG. Placement of unilateral lag screw through the lateral mass of C-1: Description of a novel technique. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;19:128–32. doi: 10.3171/2013.4.SPINE12826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yi P, Dong L, Tan M, Wang W, Tang X, Yang F, et al. Clinical application of a revised screw technique via the C1 posterior arch and lateral mass in the pediatric population. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2013;49:159–65. doi: 10.1159/000358807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abeloos L, De Witte O, Walsdorff M, Delpierre I, Bruneau M. Posterior osteosynthesis of the atlas for nonconsolidated Jefferson fractures: A new surgical technique. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:E1360–3. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318206cf63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hein C, Richter HP, Rath SA. Atlantoaxial screw fixation for the treatment of isolated and combined unstable Jefferson fractures - experiences with 8 patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002;144:1187–92. doi: 10.1007/s00701-002-0998-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Easter JS, Barkin R, Rosen CL, Ban K. Cervical spine injuries in children, part II: Management and special considerations. J Emerg Med. 2011;41:252–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rozzelle CJ, Aarabi B, Dhall SS, Gelb DE, Hurlbert RJ, Ryken TC, et al. Management of pediatric cervical spine and spinal cord injuries. Neurosurgery. 2013;72(Suppl 2):205–26. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318277096c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kontautas E, Ambrozaitis KV, Kalesinskas RJ, Spakauskas B. Management of acute traumatic atlas fractures. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18:402–5. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000177959.49721.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levine AM, Edwards CC. Fractures of the atlas. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:680–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Zhou Y, Zhang ZF, Li CQ, Zheng WJ, Zhang Y, et al. Direct repair of displaced anterior arch fracture of the atlas under microendoscopy: Experience with seven patients. Eur Spine J. 2012;21:347–51. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1965-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mixter SJ, Osgood RB. IV. Traumatic lesions of the atlas and axis. Ann Surg. 1910;51:193–207. doi: 10.1097/00000658-191002000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Payer M, Luzi M, Tessitore E. Posterior atlanto-axial fixation with polyaxial C1 lateral mass screws and C2 pars screws. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2009;151:223–9. doi: 10.1007/s00701-009-0198-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruf M, Melcher R, Harms J. Transoral reduction and osteosynthesis C1 as a function-preserving option in the treatment of unstable Jefferson fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:823–7. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000116984.42466.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koller H, Acosta F, Forstner R, Zenner J, Resch H, Tauber M, et al. C2-fractures: Part II. A morphometrical analysis of computerized atlantoaxial motion, anatomical alignment and related clinical outcomes. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:1135–53. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-0901-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee M, Cassinelli E, Riew KD. The feasibility of inserting atlas lateral mass screws via the posterior arch. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:2798–801. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000245902.93084.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harms J, Melcher RP. Posterior C1-C2 fusion with polyaxial screw and rod fixation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:2467–71. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200111150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong X, Dong Y, Yunbing C, Qingshui Y, Shizheng Z, Jingfa L. Posterior screw placement on the lateral mass of atlas: An anatomic study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:500–3. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000113874.82587.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blagg SE, Don AS, Robertson PA. Anatomic determination of optimal entry point and direction for C1 lateral mass screw placement. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22:233–9. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31817ff95a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gunnarsson T, Massicotte EM, Govender PV, Raja Rampersaud Y, Fehlings MG. The use of C1 lateral mass screws in complex cervical spine surgery: Indications, techniques, and outcome in a prospective consecutive series of 25 cases. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:308–16. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000211291.21766.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhee WT, You SH, Kim SK, Lee SY. Troublesome occipital neuralgia developed by c1-c2 harms construct. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2008;43:111–3. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2008.43.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang MJ, Glaser JA. Complete arcuate foramen precluding C1 lateral mass screw fixation in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis: Case report. Iowa Orthop J. 2003;23:96–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Young JP, Young PH, Ackermann MJ, Anderson PA, Riew KD. The ponticulus posticus: Implications for screw insertion into the first cervical lateral mass. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:2495–8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]