Abstract

Catecholaminergic neurons of the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM-CA neurons; C1 neurons) contribute to the sympathetic, parasympathetic and neuroendocrine responses elicited by physical stressors such as hypotension, hypoxia, hypoglycemia, and infection. Most RVLM-CA neurons express vesicular glutamate transporter (VGLUT)2, and may use glutamate as a ionotropic transmitter, but the importance of this mode of transmission in vivo is uncertain. To address this question, we genetically deleted VGLUT2 from dopamine-β-hydroxylase-expressing neurons in mice [DβHCre/0;VGLUT2flox/flox mice (cKO mice)]. We compared the in vivo effects of selectively stimulating RVLM-CA neurons in cKO vs. control mice (DβHCre/0), using channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2– mCherry) optogenetics. ChR2–mCherry was expressed by similar numbers of rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) neurons in each strain (~400 neurons), with identical selectivity for catecholaminergic neurons (90–99% colocalisation with tyrosine hydroxy-lase). RVLM-CA neurons had similar morphology and axonal projections in DβHCre/0 and cKO mice. Under urethane anesthesia, photostimulation produced a similar pattern of activation of presumptive ChR2-positive RVLM-CA neurons in DβHCre/0 and cKO mice. Photostimulation in conscious mice produced frequency-dependent respiratory activation in DβHCre/0 mice but no effect in cKO mice. Similarly, photostimulation under urethane anesthesia strongly activated efferent vagal nerve activity in DβHCre/0 mice only. Vagal responses were unaffected by α1-adrenoreceptor blockade. In conclusion, two responses evoked by RVLM-CA neuron stimulation in vivo require the expression of VGLUT2 by these neurons, suggesting that the acute autonomic responses driven by RVLM-CA neurons are mediated by glutamate.

Keywords: C1 neuron, channelrhodopsin 2, conditional knockout, gene disruption in mice, glutamate

Introduction

Catecholaminergic neurons located in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM-CA neurons) are activated by a variety of stresses (pain, hypotension, hypoxia, hypoglycemia, and infection), and contribute to the autonomic and neuroendocrine responses elicited by these stimuli (Guyenet et al., 2013). Most RVLM-CA neurons are C1 neurons, which, by definition, express all of the catalytic enzymes required for the production of adrenaline [tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DβH), and phenylethanolamine N-methyl transferase (PNMT)] (Hokfelt et al., 1974; Ross et al., 1983; Phillips et al., 2001). Despite C1 neurons having a catecholaminergic phenotype, evidence suggests that they release glutamate as a primary neurotransmitter in adult rodents. PNMT-containing terminals form asymmetric synaptic contacts, consistent with the ultrastructure of classic excitatory synapses (Milner et al., 1987, 1988, 1989; Agassandian et al., 2012; Depuy et al., 2013). Glutamate uptake by synaptic vesicles is mediated by one of three vesicular glutamate transporters (VGLUTs): VGLUT1, VGLUT2, and VGLUT3 (Bellocchio et al., 2000; Takamori et al., 2000; Gras et al., 2002; Fremeau et al., 2004). Only VGLUT2 transcripts and protein are detectable in C1 neurons of rats and mice (Stornetta et al., 2002a; Herzog et al., 2004; Rosin et al., 2006; Abbott et al., 2012). Furthermore, optogenetic activation of the C1 axons elicits monosynaptic glutamatergic excitatory postsynaptic currents in para-sympathetic preganglionic neurons in vitro (Depuy et al., 2013), which is consistent with previous in vivo pharmacological evidence (Morrison et al., 1991; Morrison, 2003; Abbott et al., 2012).

The evidence that C1 neurons use glutamate as a fast transmitter is substantial, but, for the most part, is indirect (histological and pharmacological) or has been obtained in vitro. Glutamate release by C1 neurons should rely on VGLUT2, but this has not been directly tested. The aims of the present study were to determine the contribution of VGLUT2-dependent glutamate release to RVLM-CA neuron signaling in intact mice, and to determine the significance of VGLUT2 in this process. To accomplish this aim, we crossed DβHCre/0 mice, in which noradrenergic and adrenergic neurons express Cre-recombinase, with mice in which exon 2 of the VGLUT2 gene is flanked by LoxP sites (Tong et al., 2007; Abbott et al., 2013). In the resulting progeny [DβHCre/0;VGLUT2flox/flox mice (cKO mice)], VGLUT2 is largely eliminated from the terminals of RVLM-CA neurons (Depuy et al., 2013). To determine the contribution of VGLUT2 and glutamate release to RVLM-CA neuron signaling in vivo, we compared the effects of stimulating these neurons on respiration and vagus nerve efferent activity in DβHCre/0 and cKO mice by using a Cre-dependent channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2)-based optogenetic method.

Materials and methods

Animals

Animal use was in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and was approved by the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee. DβHCre/0 mice were obtained from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center at the University of California, Davis, CA, USA [Tg(DβH-cre)KH212Gsat/Mmcd; stock no. 032081-UCD]. DβHCre/0 mice were maintained as hemizygous (Cre/0) on a C57BL/6J background. Homozygous VGLUT2(flox/flox) mice (JAX stock no. 012898; STOCK Slc17a6tm1Lowl/J) (Tong et al., 2007) were bred with DβHCre/0 mice to generate DβHCre/0;VGlut2flox/0 mice, and subsequently crossed with Vglut2flox/flox mice for two generations to generate cKO mice, in which VGLUT2 is absent from any Cre-expressing neurons (Depuy et al., 2013). A total of 11 DβHCre/0 mice (five males; six females) and 10 cKO mice (five males; five females), aged between 10 and 22 weeks, were used for these experiments.

Virus injection and fiber optic implantation

Adeno-associated virus (AAV)2–DIO–EF1α–ChR2(H134R)–mCherr y (AAV2–ChR2–mCherry) and AAV2–DIO–EF1α–ChR2(H134R)– eYFP (AAV2–ChR2–eYFP) (titer, 1012 virus molecules per milliliter) were purchased from the University of North Carolina vector core [constructs courtesy of K. Deisseroth (Stanford)]. This vector features an enhanced version of the photosensitive cationic channel ChR2 [ChR2(H134R)] fused to a fluorescent reporter, mCherry or enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (eYFP), under the control of the promoter for elongation factor 1α (EF1α). The ChR2–mCherry sequence is flanked by double lox sites (LoxP and lox 2722).

Unilateral microinjections of AAV2–ChR2–mCherry into the left rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) and placement of a fiber optic were performed under aseptic conditions in mice anesthetised with a mixture of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and dexmedetomidine (0.2 mg/kg; intraperitoneal), as previously described (Abbott et al., 2013). Adequate anesthesia was judged by the absence of the corneal and hind-paw withdrawal reflex. Additional anesthetic was administered as necessary (20% of the original dose, intraperitoneal). Following injections of AAV2–ChR2–mCherry (~400 nL) into the left RVLM, an implantable 200-lm-diameter fiber optic was placed with its tip 400 lm above the injection site (~4.7 mm ventral to the dorsal surface of the brain), and the fiber optic was secured to the skull with cyanoacrylate adhesive. The implantable fiber optic consisted of a desheathed optical fiber (core, 200 lm; numerical aperture, 0.39; Thorlabs) glued into a zirconia ferrule (outside diameter, 1.25 mm; bore, 230 µm; Precision Fiber Products). A subset of mice (DβHCre/0, N = 3; cKO, N = 2) injected with AAV2–ChR2–mCherry were not implanted with a fiber optic, and were later used to determine the response of single presumed C1 neurons to photostimulation under anesthesia. A second subset of mice (N = 3) used for in vitro experiments were injected with AAV2–ChR2–eYFP. Mice received postoperative boluses of atipemazole (α2-adrenergic antagonist, 2 mg/kg, subcutaneous), ampicillin (125 mg/kg, intraperitoneal), and ketoprofen (4 mg/kg, subcutaneous). Ampicillin and ketoprofen were read-ministered 24 h postoperatively. Mice were housed in the University of Virginia vivarium for >4 weeks after virus injection. During this time, mice gained weight normally and appeared to be unperturbed by the implanted fiber optic.

Single-unit recording and photostimulation of putative ChR2-expressing RVLM-CA neurons

Extracellular recordings of RVLM neurons were obtained in a subset of freely breathing anesthetised mice (DβHCre/0 and cKO) with a modification of a method previously developed for rats (Abbott et al., 2012). These mice were anesthetised with urethane (1.6 g/kg dissolved in H2O, delivered intraperitoneally as a 20% w/v solution), and placed in the stereotaxic frame in a prone position. RVLM neurons located in the C1 region, i.e. immediately caudal to the facial motor nucleus and at a depth of 5–5.3 mm from the surface of the brain, were recorded by the use of glass pipettes introduced vertically in the brain. Light (8–9 mW) was delivered to the RVLM through a fiber optic inserted into the brain at a 15° angle from the vertical in the transverse plane, so that its tip was within 500 µm of the region explored during unit recordings. Faithful pulse-by-pulse neuronal activation up to 20 Hz was taken as evidence that the recorded cells were directly photostimulated and therefore probably RVLM-CA neurons.

Whole-cell recording and photostimulation of ChR2-expressing RVLM-CA neurons in slices

Slice preparation was performed as described in Depuy et al. (2013). Briefly, 6 weeks after AAV2 injection, three DβHCre/0 mice were anesthetised with a mixture of ketamine (120 mg/kg) and xylazine (12 mg/kg) given intraperitoneally, and mice were decapitated when they had been rendered unresponsive to a firm toe pinch. The brainstem was sectioned with a vibrating microtome in the transverse plane in ice-cold N-methyl-d-glucamine-substituted artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing 92 mm N-methyl-d-glucamine, 2.5 mm KCl, 1.25 mm NaH2PO4, 10 mm MgSO4, 0.5 mm CaCl2, 20 mm HEPES, 30 mm NaHCO3, 25 mm glucose, 2 mm thiourea, 5 mm sodium ascorbate, and 3 mM sodium pyruvate (~300 mOsm/kg). After incubation for 10 min at 33 °C, brain slices were transferred to aerated physiological extracellular ACSF containing 119 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm KCl, 1.25 mm NaH2PO4, 2 mm MgSO4, 2 mm CaCl2, 26 mm NaHCO3, 12.5 mm glucose, 2 mm thiourea, 5 mm sodium ascorbate, and 3 mm sodium pyruvate, and maintained at room temperature (23 °C). All recordings were performed at room temperature in submerged slices continuously perfused with aerated (95% O2, 5% CO2) physiological ACSF. Glass pipettes (tip resistance, 2–6 MΩ) were filled with a solution containing 110 mm potassium gluconate, 20 mm potassium chloride, 10 mm HEPES, 10 mm tris-phosphocreatine, 3 mm ATP-Na, 0.3 mm GTP-Na, 1 mm EGTA, 2 mm MgCl2, and 0.2% biocytin. The junction potential was 14.8 mV, and corrected membrane potentials are reported in the text and figures. Recordings were performed with a Multiclamp 700B amplifier and pclamp 10 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Signals were low-pass filtered at 4 kHz and digitised at 10 kHz. Only cells with series resistance that remained below 25 MΩ were included in the analysis. Further analysis was performed with spike2 v7.10 (CED, Cambridge, UK). Photostimulation of visually identified ChR2–eYFP-expressing neurons was performed with a 200-µm-diameter fiber optic coupled to a 473-nm DPSS laser (IkeCool Corporation, Anaheim, CA, USA), as previously described (Depuy et al., 2013). The tip of the fiber optic was positioned 150 µm above and 250 µm lateral to the recorded neuron. The fiber optic intensely illuminated an ellipse of ~0.342 mm2, and produced an estimated average irradiance of ~15 mW/mm2. Delivery of light pulses (duration, 5 ms) was triggered by a digitiser (Digidata 1440A; Molecular Devices) controlled by episodic protocols run in pclamp 10 (Molecular Devices). The fiber optic was calibrated for 5-mW steady-state output prior to each experiment.

Whole-body plethysmography and photostimulation in conscious mice

Photostimulation of the RVLM was performed as described previously (Abbott et al., 2013). Prior to implantation, the light output of each implanted optical fiber was measured with a light meter (Thorlabs), and the laser setting was adjusted to deliver 8–9 mW. This setting was later used during experiments.

Breathing patterns were measured in conscious mice by the use of unrestrained whole-body plethysmography (EMKA Technologies), as described previously (Abbott et al., 2013). The chamber was continuously flushed with dry room-temperature air delivered at 0.5 standardised liters per minute. Fluctuations in chamber pressure were amplified (×500) and acquired at 1 kHz with spike 2 software (v7.06; CED). Respiratory frequency (fR; breaths/min) was calculated on the basis of the onset of inspiration during periods of behavioral quiescence. Mice were briefly anesthetised with isoflurane while the connection between the implanted fiber optic and the laser delivery system was established. Recordings were initiated at least 30 min after the mice had regained consciousness. To evaluate the effects of photostimulation on fR, 10-s trains of light pulses (duration, 5 ms) were delivered at various frequencies (5–25 Hz) during behavioral quiescence. The reported changes in fR reflect the average response of two or three trials at each stimulus frequency per mouse (inter-trial variability during 20-Hz trials: DβHCre/0, 7.6 ± 0.4 breaths/min; cKO, 3.5 ± 0.5 breaths/min; N = 8 each).

Recording of vagus nerve efferent activity in urethane-anesthetised mice

Recordings of the vagus nerve were performed under urethane anesthesia (1.6 g/kg dissolved in H2O delivered intraperitoneally in a 20% w/v solution). Depth of anesthesia was assessed by absence of the corneal and hind-paw withdrawal reflex. Additional anesthetic was administered as necessary (10% of the original dose, intraperitoneal). Body temperature was maintained at 37.2 ± 0.5 °C with a servo-controlled temperature pad (TC-1000; CWE). Following induction of anesthesia, the fiber optic was connected to the laser, and mice were then placed in a stereotaxic frame in the supine position. A tracheostomy was performed, and mice were mechanically ventilated with pure oxygen (MiniVent type 845; Hugo-Sachs Electronik). Fine Teflon-coated silver wires were placed subcutaneously in the chest area to record the electrocardiogram (ECG) and heart rate. To record vagus nerve efferent activity, ~15 mm of the vagus nerve was dissected free from the carotid arteries in the neck, and the distal end of the isolated nerve segment was crushed, amounting to a vagotomy. Following vagotomy, the central respiratory pattern became desynchronised from the ventilator, thereby establishing the loss of afferent vagus nerve activity. At this point, the rate and volume of mechanical ventilation were adjusted to eliminate spontaneous breathing (170–220 r.p.m. at 7–8 µL/g), the adequacy of anesthesia was rechecked, and the paralyzing agent vecuronium was administered (0.1 mg/kg, intraperitoneal). After this point, adequate anesthesia was determined by the absence of changes in heart rate in response to a firm hind-paw pinch. The vagus nerve ipsilateral to the implanted fiber optic, and anterior to the section of the nerve crushed earlier, was placed on a bipolar platinum–iridium wire electrode (part no. 778000; A-M Systems) and embedded in silicone (Kwik-Sil, WPI). Physiological signals were filtered and amplified (ECG, 10–1000 Hz, ×1000; vagus, 30–3000 Hz, ×10 000) (BMA-400; CWE) and acquired in spike 2 software (v7.06; CED). Post hoc high-pass filtering of vagus nerve recordings (high pass, 100 Hz; transition, 50 Hz) was used in cases showing ECG contamination. Three cases were excluded from analysis because of failed nerve recordings. The vagus nerve response to RVLM photostimulation was analysed by measuring the area under the curve (AUC) relative to the prestimulus AUC of waveform averages of rectified vagus nerve activity triggered from the first light pulse of 10–20 stimulation trials (1-s train of 5-ms pulses at 5, 10 and 20 Hz) delivered at 0.1 Hz. The resulting value was defined as the evoked vagus nerve activity during photostimulation [in arbitrary units (a.u.)]. To account for potential differences in the quality of the vagus nerve recording between mice, the evoked vagus nerve activity during photostimulation was normalised with respect to respiratory-related oscillations in vagus nerve activity [rectified and smoothed (τ = 0.01)] during administration of CO2 (6–7%) in response to the inspired gas. These oscillations reflect the periodic changes in para-sympathetic preganglionic neuron activity driven by the central respiratory pattern generator. Thus: normalised evoked vagus nerve activity during photostimulation (a.u.) = [(AUC vagus nerve activity during stimulation) – (AUC vagus nerve activity during the presti-mulus period)]/(range of respiratory-related oscillations in vagus nerve activity during CO2 administration).

For presentation purposes, the range of respiratory-related vagus nerve activity was assigned a scale of 0–100 a.u., and traces of nerve recordings and waveform averages were scaled accordingly. Note that 0 a.u. in vagus nerve recordings does not reflect absolute zero activity. Paired-pulse stimulation was evaluated in DβHCre/0 mice by generating waveform averages of paired 50-ms laser pulses delivered at 0.2 Hz. Prazosin (1 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) was administered in DβHCre/0 and cKO mice to evaluate the effects of central α1-adrenoreceptor blockade on the vagal response to photostimulation.

Histological procedures

Following completion of the in vivo experiments, mice were lethally anesthetised with urethane, and transcardially perfused with 50 mL of heparinised saline followed by 100 mL of freshly prepared 2% paraformaldehyde in 100 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Brains were extracted and post-fixed at 4 °C for 24–48 h in the same fixative. Coronal sections were cut at 30 µm on a vibrating microtome, and stored in a cryoprotectant solution (20% glycerol plus 30% ethylene glycol in 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) at −20 °C.

Immunohistochemical procedures and microscopy were performed as previously described (Abbott et al., 2013). The following antibodies were used: mCherry protein was detected with anti-DsRed (rabbit polyclonal, 1 : 500; Clontech #632496; Clontech Laboratories) fol-lowed by Cy3-tagged anti-rabbit IgG (1 : 200; Jackson ImmunoRe-search Laboratories); TH was detected with a sheep polyclonal antibody (1 : 2000, Millipore #AB1542; EMD Millipore) followed by Alexafluor488-tagged donkey anti-sheep antibody (1 : 200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories); and eYFP was detected with a chicken polyclonal antibody (1 : 2000; Aves Labs, Tigard, OR, USA) followed by Alexafluor488-tagged donkey anti-chicken antibody (1 : 200, Jackson code 703-545-155; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories).

The slices used for whole-cell recordings in vitro were rinsed, and incubated first in blocking solution with a Triton concentration of 0.5%, to enhance antibody penetration, and then in primary antibodies for TH and eYFP, as described above. eYFP was detected with a chicken polyclonal antibody (1 : 2000; Aves Labs) followed by Alexafluor488-tagged donkey anti-chicken antibody (1 : 200, Jackson code 703-545-155; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Slices were then rinsed and incubated with secondary antibodies (as described above), and with NeutrAvidin-Dylight-649 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Suwanee, GA, USA) to identify biocytin. Slices were finally rinsed and mounted, and coverslips were affixed.

All brain sections were examined under bright field and epifluorescence with a Zeiss AxioImager Z.1 microscope equipped with a computer-controlled stage, by use of neurolucida software (v10; MBF Bioscience). Cell counts were performed in a 1:3 series aligned to the caudal extent of the facial motor nucleus, designated as −6.48 mm from bregma, after an atlas (Paxinos & Franklin, 2004). Images were obtained with a Zeiss MRC camera as TIFF files (1388 × 1040 pixels), and imported into canvas software (v10; ACD Systems) for the composition of figures. Output levels were adjusted to include all information-containing pixels. Balance and contrast were adjusted to reflect true rendering as much as possible. No other ‘photo-retouching’ was performed.

Statistical analyses

Microsoft Excel 2010 and graphpad prism 6 were used to collate and analyse data. The distribution of the data was tested for normality (D’Agostino and Pearson omnibus), and significant differences between samples were determined with one-way anova (Kruskal– Wallis for non-Gaussian data) and two-way anovas, and unpaired two-tailed t-tests (Mann–Whitney test for non-Gaussian data) with a significance threshold of α = 0.05. Results are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean unless noted otherwise.

Results

ChR2-mCherry expression by RVLM-CA neurons in DβHCre/0 and cKO mice, and optical fiber placements

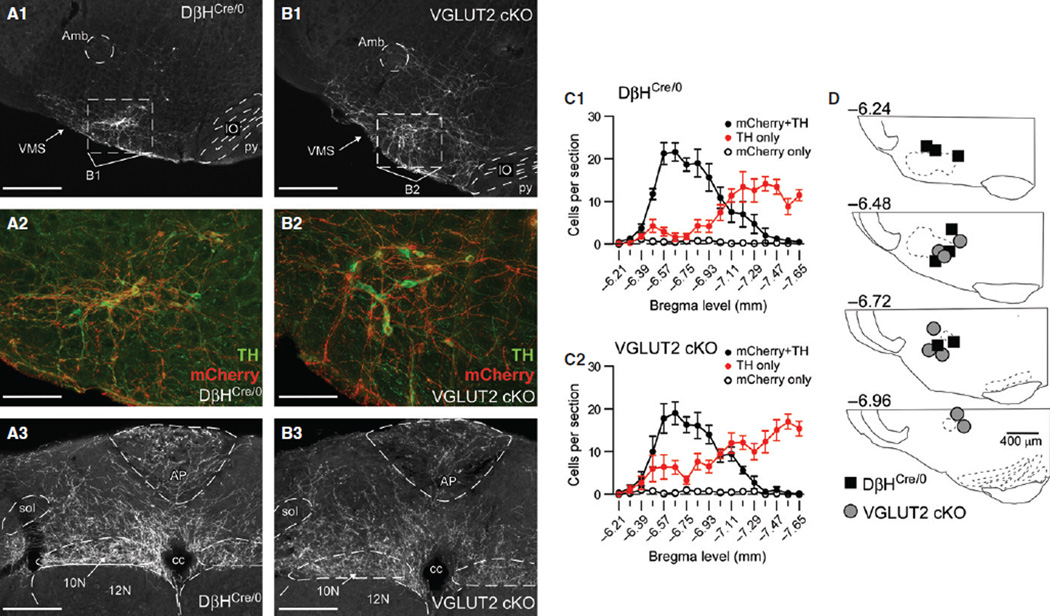

In DβHCre/0 mice (N = 8), 146 ± 19 ChR2–mCherry-positive neurons were identified in the RVLM (1:3 series; actual numbers of ChR2–mCherry-positive neurons were approximately three times larger). Most ChR2–mCherry-positive neurons were detectably cate-cholaminergic (i.e. expressed TH) (95.4% ± 0.9%; range, 91.7–99.4%), accounting for 68.4% ± 2.3% of the TH-positive neurons in the ipsilateral ventrolateral medulla in sections containing ChR2–mCherry-positive neurons (Fig. 1 A1, A2, and C1). In cKO mice (N = 8), 127 ± 16 ChR2-mCherry-positive neurons were identified in the RVLM, of which 94.9% ± 1.0% (range, 90.4–99.3%) were TH-positive, accounting for 57.3% ± 5.0% of the TH-positive neurons observed in sections containing ChR2–mCherry-positive neurons (Fig. 1 B1, B2, and C2). The RVLMs of DβHCre/0 and cKO mice contained a similar number of ChR2–mCherry-positive neurons (t14 = 0.78, P = 0.45), and a similar percentage of these neurons were TH-positive (t14 = 1.38, P = 0.74). Also, the rostrocaudal distribution of ChR2–mCherry-positive neurons in the RVLM was indistinguishable between DβHCre/0 and cKO mice (F16,214 = 0.23 and P = 0.99 for the interaction between genotype and bregma level) (Fig. 1 C1 and C2). The absolute number of RVLM TH-positive neurons was equivalent between strains (t14 = 2.61, P = 0.81), as was the rostrocaudal distribution of TH-positive neurons in the RVLM (F16,214 = 1.23, P = 0.24). Finally, the proportion of RVLM TH-positive neurons expressing ChR2–mCherry was not different (t14 = 4.59, P = 0.063). Importantly, the distribution and density of the ChR2–mCherry-labeled terminals were similar in DβHCre/0 and cKO mice, indicating that the absence of VGLUT2 did not alter the gross morphology and projections of RVLM-CA neurons (Fig. 1 A3 and B3).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of ChR2–mCherry-positive neurons in the RVLM, and placement of fiber optics in DβHCre/0 and cKO mice. (A1) Low-magnification image of ChR2–mCherry expression in a coronal section of the RVLM from a DβHCre/0 mouse (approximately −6.64 mm from bregma). Scale bar: 400 µm. (A2) Higher magnification of the region outlined in A1, showing immunofluorescence for ChR2–mCherry (in red) and TH (in green). Colocalisation of ChR2– mCherry and TH is indicated by orange. Scale bar: 100 µm. (A3) ChR2–mCherry-immunoreactive axons within the dorsal medulla of a DβHCre/0 mouse (approximately −7.48 mm from bregma). Scale bar: 200 µm. (B1–B3) Descriptions and scale bars are the same as in A1–A3, except that sections are from a cKO mouse. (C1 and C2) Rostrocaudal distribution of neurons expressing ChR2–mCherry, TH or both in the ipsilateral RVLM of DβHCre/0 (C1, N = 8) and cKO (C2, N = 8) mice. (D) Locations of the tips of implanted fiber optics in DβHCre/0 and cKO mice. 10N, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus; 12N, hypoglossal motor nucleus; Amb, compact formation of the nucleus ambiguous; AP, area postrema; cc, central canal; IO, inferior olive; py, pyramidal tract; sol, solitary tract; VMS, ventral medullary surface.

The tips of the optical fibers were typically found 300–500 µm above the ventral surface of the ventrolateral medulla, and had a similar distribution in DβHCre/0 and cKO mice (Fig. 1D).

Photostimulation of RVLM-CA neurons in slices and in vivo

Optical stimulation of RVLM-CA neurons in brain slices

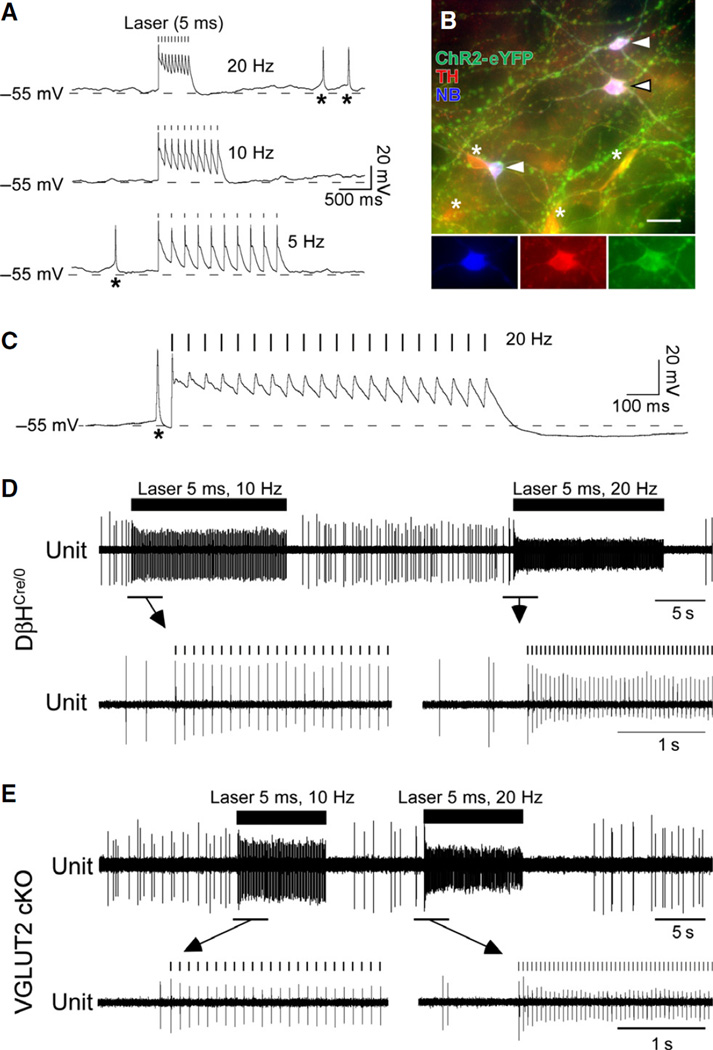

Whole-cell current clamp recordings of ChR2–eYFP-positive RVLM neurons were conducted in slices from adult DβHCre/0 mice to characterise the response of these neurons to photostimulation. ChR2– eFYP-positive neurons (nine neurons; three mice) were identified prior to patching by visualising eYFP fluorescence. These neurons were either silent or had a slow tonic discharge pattern (0.73 ± 0.32 Hz; range, 0–2.3 Hz, N = 9), and were exquisitely sensitive to photostimulation, each light pulse producing a strong depolarisation leading to a single action potential (Fig. 2A). Higher frequencies produced a tonic depolarisation without clear evidence of action potential generation (not illustrated). For this reason, we used a frequency of stimulation of <25 Hz in all our subsequent in vivo experiments. The amplitude of the stimulus-evoked spike gradually decreased during train stimulation at 10 Hz (Fig. 2A), and this was especially marked at 20 Hz (Fig. 2C). This tonic depolarisation is a characteristic of the particular ChR2 variant (H134R) used in this study (Boyden et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2009), and may be caused by fast sodium channel inactivation resulting from ChR2-dependent tonic depolarisation. All recorded neurons were filled with biocytin, and, after histological processing, every recovered biocytin-filled neuron (N = 6) contained eYFP and TH, demonstrating that they were ChR2-expressing RVLM-CA neurons (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Characteristics of the response of ChR2–expressing neurons to light stimulation in DβHCre/0 and cKO mice. (A) Current-clamp recording of a ChR2–eYFP-positive RVLM neuron in a slice (DβHCre/0 mouse) during 20-Hz, 10-Hz and 5-Hz stimulation (10 × 5-ms pulses). Each light pulse is followed by a short-latency depolarisation and an action potential. Asterisks indicate spontaneous action potentials. (B) Example of biocytin-filled RVLM-CA neurons that were photo-responsive (arrowheads). All three neurons expressed ChR2–eYFP and TH. Asterisks indicate CHR2–eYFP-positive, TH-positive neurons not labeled with biotin. Inserts correspond to the middle cell in the main panel (black-rimmed arrowhead), and show immunofluorescence for each marker separately. (C) Response of a ChR2–eFYP-positive RVLM-CA neuron to a 1-s stimulus train (20 Hz with 5-ms pulses), illustrating the reduction in action potential amplitude after the first light-induced spike and the hyperpolarisation that follows the stimulus train. (D) Extracellular recording of a single putative ChR2–mCherry-positive RVLM-CA neuron during photostimulation (10 Hz and 20 Hz with 5-ms pulses) in an anesthetised DβHCre/0 mouse. Expanded traces (below) show the pulse-by-pulse activation typical of ChR2-expressing neurons, and the gradual reduction in spike amplitude during stimulation and the silent period following the stimulus train. (E) Identical experiment in a cKO mouse.

Photostimulation of putative RVLM-CA neurons in vivo

These experiments were designed to compare the response of putative RVLM-CA neurons to photostimulation in DβHCre/0 and cKO mice. We recorded from neurons located immediately caudal to the facial motor nucleus in a region corresponding to the site of virus injection. We found four neurons in three DβHCre/0 mice and two neurons in two cKO mice in which neuronal activity could be entrained by stimulus trains up to 20 Hz (Fig. 2D and E). These neurons were spontaneously active and discharged tonically (range, 1.8–5.6 Hz), as opposed to the ON–OFF respiratory synchronous discharge that is typical of most non-catecholaminergic neurons in this region of the brain (Schreihofer & Guyenet, 1997). In both strains, the amplitude of the extracellular action potential decreased during photostimulation at frequencies >5 Hz. The decrease in spike amplitude was gradual, reaching steady state after 3–10 pulses, and reversible upon interruption of the stimulus (Fig. 2D and E). The same phenomenon has been previously described for ChR2-expressing C1 cells in rats (Abbott et al., 2009). The decrease in extracellular spike amplitude is consistent with the reduced action potential amplitude observed in vitro (Fig. 2A and C). The silent period that followed high-frequency stimulation in vivo was presumably caused by hyperpolarisation, which was observable in the intracellular recordings in slices (Fig. 2C). Together, the evidence suggests that ChR2–mCherry-positive neurons are reliably entrained to stimulus frequencies up to 20 Hz, and that the stimulus–response relationship of putative ChR2–mCherry-positive RVLM-CA neurons is comparable in DβHCre/0 and cKO mice.

In summary, the anatomical and electrophysiological evidence revealed no differences between DβHCre/0 and cKO mice with regard to the morphology and distribution of RVLM-CA neurons, the level of expression of ChR2–mCherry by these neurons, and their response to light.

Respiratory effects produced by optogenetic stimulation of RVLM-CA neurons in DβHCre/0 and cKO mice

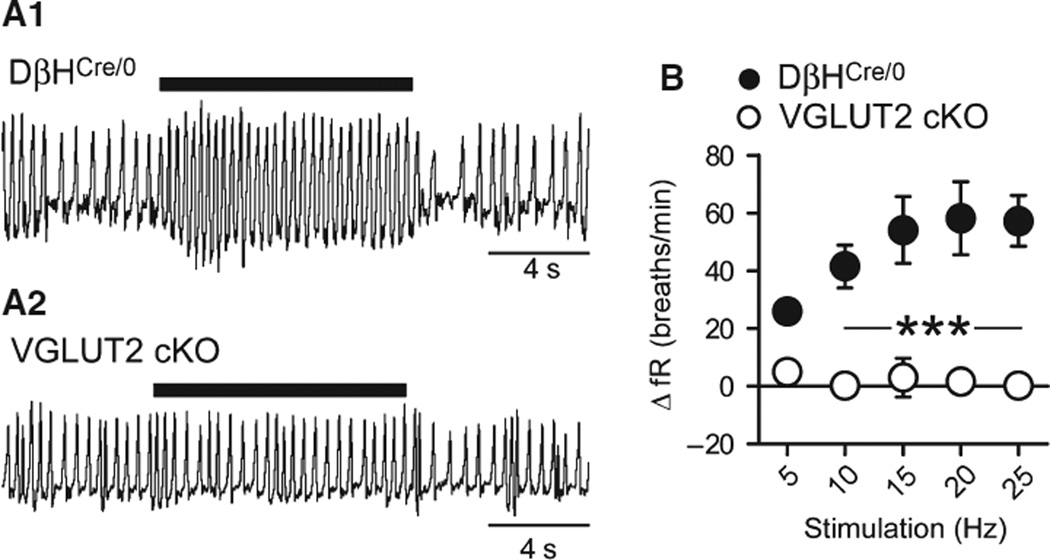

During behavioral quiescence, DβHCre/0 and cKO mice had similar fR values (DβHCre/0 vs. cKO, 131 ± 10 vs. 148 ± 3 breaths/min, t12 = 1.7, P = 0.12). Photostimulation increased fR in DβHCre/0 mice (Fig. 2A), as reported previously (Abbott et al., 2013). The increase in fR increased with light-pulse frequency up to a stimulus frequency of 15 Hz (+54.1 ± 11.6 breaths/min, N = 7). In contrast, photosti-mulation had no effect on fR in cKO mice (+3.1 ± 6.7 breaths/min, N = 7) (F4,48 = 6.62 and P = 0.0003 for the interaction between stimulation frequency and genotype; Fig. 3A and B).

Fig. 3.

Effect of stimulating RVLM-CA neurons on fR in DβHCre/0 and cKO mice. (A) Original plethysmography traces (inspiration upward) of a DβHCre/0 mouse (upper trace) and a cKO mouse (lower trace) during photostimulation (5-ms pulses at 20 Hz, 10-s train). (B) Relationship between photostimulus frequency and increase in fR in DβHCre/0 (N = 7) and cKO (N = 7) mice. ***P < 0.001 for DβHCre/0 vs. cKO (Bonferroni post hoc test following repeated measures anova).

Vagal efferent activity elicited by optogenetic stimulation of RVLM-CA neurons in DβHCre/0 and cKO mice

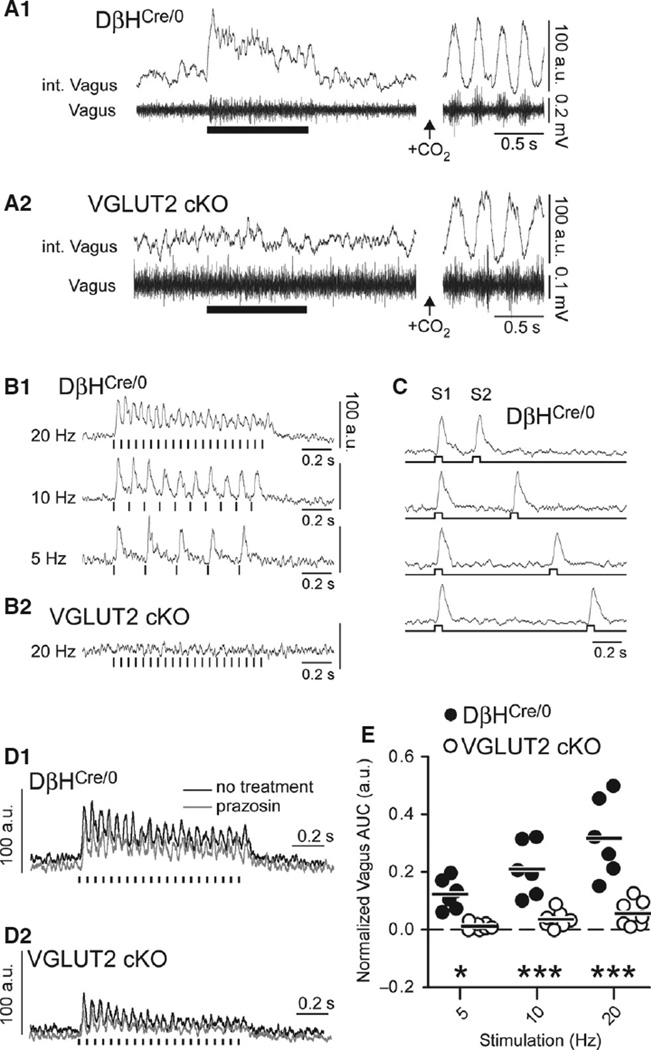

RVLM-CA neurons densely innervate the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, which contains parasympathetic preganglionic neurons (Fig. 1 A3 and B3) (Depuy et al., 2013). Optogenetic experiments in slices maintained at room temperature have indicated that this connection is monosynaptic and primarily glutamatergic (Depuy et al., 2013).

In urethane-anesthetised DβHCre/0 mice, photostimulation of RVLM-CA neurons at 20 Hz activated vagus nerve efferents (Fig. 4 A1), with an onset latency of 24.1 ± 1.3 ms and latency to peak of 37.5 ± 1.7 ms from the start of the light-pulse train. Stimulation at 5 Hz and 10 Hz produced faithful short-latency responses that followed each light pulse (Fig. 4 B1). Unlike the sympathetic nerve response to photostimulation of RVLM-CA neurons (Abbott et al., 2012), the vagus nerve response showed negligible paired-pulse depression when 50-ms pulses were delivered at intervals spanning 1000 ms, with a minimum interval of 250 ms (F3,4 = 3.36, P = 0.14; Fig. 4C). However, during 20-Hz stimulation, a modest accommodation in vagus nerve response was observed during the stimulus (1 s).

Fig. 4.

Effect of stimulating RVLM-CA neurons on efferent vagus nerve activity in DβHCre/0 and cKO mice. (A1 and A2) Left panel: integrated (upper trace) and raw (lower trace) recording of multi-unit vagus nerve activity in urethane-anesthetised DβHCre/0 (A1) and cKO (B2) mice, showing activation by photostimulation (5-ms pulses at 20 Hz, 1-s train). Right panel: respiratory-related oscillations in vagus nerve activity caused by hypercapnia in the same mouse (7% CO2). The amplitude of oscillations in vagus activity under conditions of elevated inspired CO2 (i.e. peak to trough) was assigned a value of 100 a.u. to normalise recordings between experiments. Integrated vagus nerve activity is rectified and smoothed with a 0.03-s time constant. (B1 and B2) Normalised waveform averages of the vagal response to phot-ostimulation (5-ms pulses, 15–20 trials per trace, averaging triggered from the onset of the 1-s stimulus train) in a DβHCre/0 mouse (B1) and a cKO mouse (B2). (C) Waveform average of the vagal response to paired-pulse stimulation (50-ms pulses, identified by S1 and S2) in a DβHCre/0 mouse; note that the magnitude of the second burst was similar regardless of the delay of the second pulse of light down to 250 ms. (D) Example of the of the vagal response to photostimulation (5-ms pulses at 20 Hz) in a DβHCre/0 mouse (D1) and a cKO (D2) mouse before and after α1-adrenoreceptor blockade (prazosin, 1 mg/kg). Waveforms were generated by averaging 10– 15 trials per trace. Note that the cKO mouse used in the example had the largest response of all cKO mice tested. (E) Group data of the normalised vagus nerve activity during photostimulation (see Materials and methods) in DβHCre/0 (N = 6) and cKO (N = 7) mice. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 for DβHCre/0 vs. cKO by the Bonferroni post hoc test.

In contrast to the observations in DβHCre/0 mice, photostimulation evoked no detectable vagal response in four of seven cKO mice tested (Fig. 4 A2 and B2), and a small discharge during 20-Hz stimulation in three of seven cKO mice (Fig. 4 D2). The discharge observed in responsive cKO mice had the same kinetics as the vagal response in DβHCre/0 mice, but the amplitude of the response was much smaller when normalised to the fluctuations of vagal activity present during exposure of the mice to elevated CO2 (Fig. 4D).

Regardless of strain, administration of the α1-adrenoreceptor antagonist prazosin, at a concentration sufficient to block central α1-adrenoreceptors (Menkes et al., 1981), did not alter the vagal activation caused by photostimulation (DβHCre/0 vs. responsive cKO, +2.2% ± 14.0% vs. −0.4% ± 12.7% change in vagal response after prazosin; F1,9 = 0.21 and P = 0.66 for the effect of prazosin) (Fig. 4D). Thus, the evoked vagal responses observed in DβHCre/0 and responsive cKO mice are unlikely to be generated by catecholamine release.

In summary, RVLM-CA neuron photostimulation produced much greater activation of the vagus nerve in DβHCre/0 mice than in cKO mice at all stimulation frequencies examined (F2,22 = 13.11 and P = 0.0002 for the interaction between stimulus frequency and genotype) (Fig. 4E).

Discussion

The present results show that VGLUT2 deletion from RVLM-CA neurons has no detectable impact on the number and morphology of these neurons, but almost completely eliminates two of the acute effects of activating these neurons in vivo. This work highlights the importance of VGLUT2 and, by inference, glutamate release in the physiological effects of RVLM-CA neuron stimulation in the intact mouse.

Evidence for deletion of VGLUT2 from RVLM-CA neurons

In an earlier study, we demonstrated that VGLUT2 immunoreactivity is almost completely absent from virally labeled RVLM-CA neuron terminals in the brains of cKO mice (Depuy et al., 2013). In that study, only 8% of virally labeled axonal varicosities originating from RVLM-CA neurons contained detectable VGLUT2 immunoreactivity in cKO mice, as compared with 97% in DβHCre/0 mice (Depuy et al., 2013). At the resolution of light microscopy, the appearance of VGLUT2 immunoreactivity in the terminals of RVLM-CA neurons in cKO mice may reflect superposition of virally labeled terminals and glutamatergic boutons of unknown origin. Other investigators have shown that VGLUT2 expression and function are effectively eliminated in Cre-expressing neurons when various Cre-driver mouse lines are crossed with the VGLUT2flox/flox mouse line used in the present study (Tong et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2010; Fortin et al., 2012). On this basis, we conclude that VGLUT2 was effectively deleted from most but probably not all Cre-expressing noradrenergic and adrenergic neurons in our cKO mice.

cKO mice had no obvious abnormalities in the number, morphology and projection pattern of virally labeled RVLM-CA neurons, suggesting that VGLUT2-dependent vesicular glutamate release is not essential for the development of these neurons. This result is consistent with prior evidence that RVLM-CA neurons have normal embryological development in VGLUT2-null mutant mice (Wallen-Mackenzie et al., 2006), and contrasts with evidence that VGLUT2 expression is important for the survival and the development of mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons after birth (Fortin et al., 2012).

Photostimulation of RVLM-CA in slices and in vivo

The present whole-cell recordings have demonstrated that ChR2-expressing RVLM-CA neurons respond to light pulses in conventional manner. As in other neurons, the relatively slow kinetics of the current elicited by ChR2(H134R) enable reliable neuronal activation only up to 20 Hz (Wang et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2009). At frequencies >10 Hz, fast sodium channel inactivation during tonic depolarisation may have caused a gradual reduction in action potential amplitude, and a reduction in the amplitude of extracellular spikes in vivo.

We did not obtain proof that the RVLM neurons that were light-activated on a pulse-by-pulse basis in vivo were ChR2–mCherry-positive catecholaminergic neurons. Conceivably, these cells could have been non-catecholaminergic neurons that were driven synaptically in DβHCre/0 mice, but this is implausible in the case of cKO mice, in which the RVLM-CA neurons do not release glutamate.

Glutamate mediates the stimulatory effects of the C1 cells on respiration and the parasympathetic outflow in vivo

Up to 99% of the ChR2–mCherry-expressing neurons were demon-strably catecholaminergic in DβHCre/0 and cKO mice. The RVLM contains catecholaminergic neurons primarily of the C1 phenotype (i.e. PNMT-expressing neurons), along with a small proportion of A1 neurons (i.e. noradrenergic neurons devoid of PNMT). Thus, given the location of ChR2–mCherry-expressing neurons in this study, most of these neurons are likely to be C1 rather than A1 neurons. A1 neurons, along with other noradrenergic neurons in the brainstem, do not commonly express transcripts for VGLUTs in rats (Stornetta et al., 2002a), and are thought to use noradrenaline as a primary neurotransmitter. The fact that α1-adrenoreceptor blockade did not reduce the vagal response in DβHCre/0 mice indicates that the release of noradrenaline from A1 (or C1) neurons or downstream targets was not essential for the observed responses. Accordingly, the robust and consistent respiratory and vagal stimulation produced by activation of RVLM-CA neurons in DβHCre/0 mice was almost certainly caused by the activation of RVLM-CA neurons that normally express VGLUT2. Also, given that cKO mice were almost completely unresponsive to identical stimulation of a similar population of RVLM-CA neurons, the combined evidence indicates that VGLUT2, and thereby glutamate release, is necessary for physiological responses to C1 neuron stimulation.

The loss of VGLUT2 in catecholaminergic neurons that are activated during C1 stimulation may amplify the differences observed between DβHCre/0 and cKO mice. VGLUT2 is expressed by the C2 and C3 adrenergic population in rats (Stornetta et al., 2002a), but little is known about the function of these neurons. The circuit responsible for the respiratory stimulation elicited by photostimulation of RVLM-CA neurons is unknown. A direct connection of the C1 cells to the pre-Bötzinger complex is anatomically plausible, but many other routes are conceivable, given the complexity of the projection pattern of the RVLM-CA neurons (Card et al., 2006; Abbott et al., 2013). RVLM-CA neurons monosynaptically activate the preganglionic neurons of the dorsal vagal complex in mouse brain slices (Depuy et al., 2013), which probably underlies the vagal efferent responses evoked by RVLM photostimulation in vivo, although indirect circuits may also contribute to this effect.

A minority of cKO mice retained a weak vagal response that resembled the response observed in DβHCre/0 mice. The fast kinetics of the residual vagal response in cKO mice are inconsistent with the actions of a slow-acting metabotropic transmitter, be it a catecholamine or peptide. As already mentioned, noradrenaline release from stimulated C1 or A1 neurons is unlikely to explain the vagal response in cKO mice, as it was insensitive to α1-adrenoreceptor blockade. Other possible explanations for the small residual effect seen in a fraction of the cKO mice are the release of an unidentified transmitter from RVLM-CA, and the upregulation of either VGLUT1 or VGLUT3. However, in this case, a greater proportion of cKO mice should have had an appreciable response to photostimulation.

Failed or incomplete deletion of the VGLUT2 gene in a minority of RVLM-CA neurons sufficiently explains the small vagal response found in a minority of cKO mice. By experimental design, both the expression of ChR2–mCherry and the deletion of the VGLUT2 gene were contingent on the presence of genomic Cre driven from the DβH promoter. For this reason, we predicted that RVLM-CA neurons expressing Cre-dependent ChR2–mCherry would be neurons that express sufficiently high levels of Cre to also eliminate VGLUT2 in the cKO mouse, theoretically bypassing issues arising from variegated expression of Cre in the DβHCre/0 mouse line. However, the efficacy of Cre recombination of LoxP sites within the VGLUT2 gene may be influenced by the chromosomal location of the LoxP sites and the distance between these sites (Schmidt-Supprian & Rajewsky, 2007; Liu et al., 2013). Given this, differences in the recombination efficiency of the virally delivered floxed transgene vs. the floxed VGLUT2 gene may result in the expression of ChR2–mCherry in a subset of RVLM-CA neurons that retain functional VGLUT2 expression in the cKO mouse. This possibility accounts for the reduced amplitude of the vagal response in cKO mice, as well as the similarities in the kinetics of the vagal response in both strains. It would also account for the small fraction of virally labeled RVLM-CA terminals that appear to be VGLUT2-immunoreactive in cKO mice (Depuy et al., 2013).

Altogether, the evidence supports the conclusion that VGLUT2 and glutamate release are required for the effects of RVLM-CA neuron stimulation in vivo. This interpretation is consistent with the presence of VGLUT2 mRNA and protein in C1 neurons in rodents (Stornetta et al., 2002b, 2005; Herzog et al., 2004; Abbott et al., 2013) and the fact that optogenetic activation of RVLM-CA terminals in slices produces fast excitatory postsynaptic currents that are blocked by ionotropic glutamate antagonists (Depuy et al., 2013).

Do C1 neurons release catecholamines?

In mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons, VGLUT2 may serve to facilitate the vesicular packaging of catecholamine (Hnasko et al., 2010). The same mechanism could potentially exist in C1 neurons, which co-express vesicular monoamine transporter 2 and VGLUT2 (Sevigny et al., 2008; Depuy et al., 2013). If vesicular packaging of catecholamine depends on VGLUT2 in C1 neurons, the ability of these neurons to release catecholamine could be severely curtailed in cKO mice, which could explain the absence of detectable cate-cholamine release during RVLM-CA neuron stimulation in cKO mice. However, this interpretation requires the responses elicited in DβHCre/0 mice to have a prominent catecholaminergic component, which does not appear to be true [see Depuy et al. (2013), Abbott et al. (2013), and the present results]. We did not explore the effect of β-adrenoreceptor blockade on the vagal response in the present study, because the excitatory effect of catecholamines on dorsal vagal motoneurons have been reported to be entirely mediated by α1-adrenoreceptors (Martinez-Pena y Valenzuela et al., 2004). Furthermore, we have previously shown that β-adrenoreceptor blockade does not attenuate the respiratory response to RVLM-CA neuron stimulation (Abbott et al., 2013). Together, the lack of effect of α1-adrenoreceptors indicates that catecholamine release makes, at most, a very minor contribution to the acute respiratory and parasympa-thetic effects produced by RVLM-CA neuron stimulation in vivo. Clearly, this observation does not eliminate the possibility that cate-cholamines are released from C1 neurons in other conditions.

An uninvestigated possibility is that catecholamines released by C1 neurons have effects that are delayed. Indeed, catecholamines often produce long-term potentiation or even metaplasticity that develops over a much longer time period than the acute responses that we have examined (Neverova et al., 2007; Inoue et al., 2013). A similar argument can be made for any one of the neuropeptides known to be expressed by C1 neurons [for a review, see Guyenet et al. (2013)]. Another possibility is that the catecholamines released by C1 neurons activate the surrounding glia, and have only minor effects on synaptic transmission (O’Donnell et al., 2012).

In conclusion, we have shown that genetic deletion of VGLUT2 from RVLM-CA neurons abolishes the acute respiratory and para-sympathetic activation produced by selectively stimulating these neurons in mice. The collective evidence indicates that C1 neurons regulate the autonomic nervous system through the synaptic release of glutamate, which is consistent with their role in mediating rapid counter-regulatory responses to physical stresses.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge R. L. Stornetta, S. D. Depuy and M. B. Coates for assistance with microscopy and mouse breeding. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants HL28785 and HL74011 to P. G. Guyenet), and a postdoctoral fellowship to S. B. G. Abbott from the American Heart Association (11post7170001).

Abbreviations

- AAV

adeno-associated virus

- AAV2–ChR2–eYFP

AAV2–DIO–EF1α–ChR2 (H134R)–eYFP

- AAV2–ChR2–mCherry

AAV2–DIO–EF1α–ChR2(H134R)–hmCherry

- ACSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- a.u.

arbitrary units

- AUC

area under the curve

- ChR2

channel channelrhodopsin-2

- cKO

DβHCre/0;VG LUT2flox/flox

- DβH

dopamine-β-hydroxylase

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- EF1α

elongation factor 1α

- eYFP

enhanced yellow fluorescent protein

- fR

respiratory frequency

- PNMT

phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase

- RVLM

rostral ventrolateral medulla

- RVLM-CA

neurons catecholaminergic neurons of the rostral ventrolateral medulla

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- VGLUT

vesicular glutamate transporter

References

- Abbott SB, Stornetta RL, Socolovsky CS, West GH, Guyenet PG. Photostimulation of channelrhodopsin-2 expressing ventrolateral medullary neurons increases sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure in rats. J. Physiol. 2009;587:5613–5631. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.177535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott SB, Kanbar R, Bochorishvili G, Coates MB, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. C1 neurons excite locus coeruleus and A5 noradren-ergic neurons along with sympathetic outflow in rats. J. Physiol. 2012;590:2897–2915. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.232157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott SB, Depuy SD, Nguyen T, Coates MB, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. Selective optogenetic activation of rostral ventrolat-eral medullary catecholaminergic neurons produces cardiorespiratory stimulation in conscious mice. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:3164–3177. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1046-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agassandian K, Shan Z, Raizada M, Sved AF, Card JP. C1 catecholamine neurons form local circuit synaptic connections within the rostroventrolateral medulla of rat. Neuroscience. 2012;227:247–259. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellocchio EE, Reimer RJ, Fremeau RT, Jr, Edwards RH. Uptake of glutamate into synaptic vesicles by an inorganic phosphate transporter. Science. 2000;289:957–960. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Deisseroth K. Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:1263–1268. doi: 10.1038/nn1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card JP, Sved JC, Craig B, Raizada M, Vazquez J, Sved AF. Efferent projections of rat rostroventrolateral medulla C1 catechol-amine neurons: implications for the central control of cardiovascular regulation. J. Comp. Neurol. 2006;499:840–859. doi: 10.1002/cne.21140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depuy SD, Stornetta RL, Bochorishvili G, Deisseroth K, Witten I, Coates MB, Guyenet PG. Glutamatergic neurotransmission between the C1 neurons and the parasympathetic preganglionic neurons of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:1486–1497. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4269-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin GM, Bourque MJ, Mendez JA, Leo D, Nordenankar K, Birg-ner C, Arvidsson E, Rymar VV, Berube-Carriere N, Claveau AM, Descarries L, Sadikot AF, Wallen-Mackenzie A, Trudeau LE. Glutamate corelease promotes growth and survival of midbrain dopamine neurons. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:17477–17491. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1939-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremeau RT, Voglmaier S, Seal RP, Edwards RH. VGLUTs define subsets of excitatory neurons and suggest novel roles for glutamate. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gras C, Herzog E, Bellenchi GC, Bernard V, Ravassard P, Pohl M, Gasnier B, Giros B, El Mestikawy S. A third vesicular gluta-mate transporter expressed by cholinergic and serotoninergic neurons. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:5442–5451. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05442.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet PG, Stornetta RL, Bochorishvili G, Depuy SD, Burke PG, Abbott SB. Invited Review EB 2012: C1 neurons: the body’s EMTs. Am. J. Physiol-Reg. I. 2013;305:R187–R204. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00054.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog E, Gilchrist J, Gras C, Muzerelle A, Ravassard P, Giros B, Gaspar P, El Mestikawy S. Localization of VGLUT3, the vesicular glutamate transporter type 3, in the rat brain. Neuroscience. 2004;123:983–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnasko TS, Chuhma N, Zhang H, Goh GY, Sulzer D, Palmiter RD, Rayport S, Edwards RH. Vesicular glutamate transport promotes dopamine storage and glutamate corelease in vivo. Neuron. 2010;65:643–656. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokfelt T, Fuxe K, Goldstein M, Johansson O. Immunohisto-chemical evidence for the existence of adrenaline neurons in the rat brain. Brain Res. 1974;66:235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue W, Baimoukhametova DV, Fuzesi T, Cusulin JI, Koblinger K, Whelan PJ, Pittman QJ, Bains JS. Noradrenaline is a stress-associated metaplastic signal at GABA synapses. Nat. Neurosci. 2013;16:605–612. doi: 10.1038/nn.3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JY, Lin MZ, Steinbach P, Tsien RY. Characterization of engineered channelrhodopsin variants with improved properties and kinetics. Biophys. J. 2009;96:1803–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Abdel SO, Zhang L, Duan B, Tong Q, Lopes C, Ji RR, Lowell BB, Ma Q. VGLUT2-dependent glutamate release from noci-ceptors is required to sense pain and suppress itch. Neuron. 2010;68:543–556. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Willet SG, Bankaitis ED, Xu Y, Wright CV, Gu G. Non-parallel recombination limits cre-loxP-based reporters as precise indicators of conditional genetic manipulation. Genesis. 2013;51:436–442. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Pena y Valenzuela I, Rogers RC, Hermann GE, Travagli RA. Norepinephrine effects on identified neurons of the rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastr. L. 2004;286:G333–G339. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00289.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menkes DB, Baraban JM, Aghajanian GK. Prazosin selectively antagonizes neuronal responses mediated by alpha-1-adrenoceptors in brain. N.-S. Arch. Pharmacol. 1981;317:273–275. doi: 10.1007/BF00503830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner TA, Pickel VM, Park DH, Joh TH, Reis DJ. Phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase-containing neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of the rat I. Normal ultrastructure. Brain Res. 1987;411:28–45. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90678-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner TA, Morrison SF, Abate C, Reis DJ. Phenylethanol-amine N-methyltransferase-containing terminals synapse directly on sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the rat. Brain Res. 1988;448:205–222. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner TA, Abate C, Reis DJ, Pickel VM. Ultrastructural localization of phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase-like immunoreac-tivity in the rat locus coeruleus. Brain Res. 1989;478:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91471-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SF. Glutamate transmission in the rostral ventrolateral medullary sympathetic premotor pathway. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2003;23:761–772. doi: 10.1023/A:1025005020376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SF, Callaway J, Milner TA, Reis DJ. Rostral ven-trolateral medulla – a source of the glutamatergic innervation of the sympathetic intermediolateral nucleus. Brain Res. 1991;562:126–135. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neverova NV, Saywell SA, Nashold LJ, Mitchell GS, Feldman JL. Episodic stimulation of alpha1-adrenoreceptors induces protein kinase C-dependent persistent changes in motoneuronal excitability. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:4435–4442. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2803-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell J, Zeppenfeld D, McConnell E, Pena S, Nedergaard M. Norepinephrine: a neuromodulator that boosts the function of multiple cell types to optimize CNS performance. Neurochem. Res. 2012;37:2496–2512. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0818-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JK, Goodchild AK, Dubey R, Sesiashvili E, Takeda M, Chalmers J, Pilowsky PM, Lipski J. Differential expression of cat-echolamine biosynthetic enzymes in the rat ventrolateral medulla. J. Comp. Neurol. 2001;432:20–34. doi: 10.1002/cne.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosin DL, Chang DA, Guyenet PG. Afferent and efferent connections of the rat retrotrapezoid nucleus. J. Comp. Neurol. 2006;499:64–89. doi: 10.1002/cne.21105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CA, Ruggiero DA, Joh TH, Park DH, Reis DJ. Adrenaline synthesizing neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla: a possible role in tonic vasomotor control. Brain Res. 1983;273:356–361. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90862-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Supprian M, Rajewsky K. Vagaries of conditional gene targeting. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:665–668. doi: 10.1038/ni0707-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreihofer AM, Guyenet PG. Identification of C1 presympathet-ic neurons in rat rostral ventrolateral medulla by juxtacellular labeling in vivo. J. Comp. Neurol. 1997;387:524–536. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971103)387:4<524::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevigny CP, Bassi J, Teschemacher AG, Kim KS, Williams DA, Anderson CR, Allen AM. C1 neurons in the rat rostral ventrolateral medulla differentially express vesicular monoamine transporter 2 in soma and axonal compartments. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:1536–1544. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stornetta RL, Sevigny CP, Guyenet PG. Vesicular glutamate transporter DNPI/VGLUT2 mRNA is present in C1 and several other groups of brainstem catecholaminergic neurons. J. Comp. Neurol. 2002a;444:191–206. doi: 10.1002/cne.10141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stornetta RL, Sevigny CP, Schreihofer AM, Rosin DL, Guyenet PG. Vesicular glutamate transporter DNPI/GLUT2 is expressed by both C1 adrenergic and nonaminergic presympathetic vasomotor neurons of the rat medulla. J. Comp. Neurol. 2002b;444:207–220. doi: 10.1002/cne.10142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stornetta RL, Rosin DL, Simmons JR, McQuiston TJ, Vujovic N, Weston MC, Guyenet PG. Coexpression of vesicular gluta-mate transporter-3 and gamma-aminobutyric acidergic markers in rat rostral medullary raphe and intermediolateral cell column. J. Comp. Neurol. 2005;492:477–494. doi: 10.1002/cne.20742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamori S, Rhee JS, Rosenmund C, Jahn R. Identification of a vesicular glutamate transporter that defines a glutamatergic phenotype in neurons. Nature. 2000;407:189–194. doi: 10.1038/35025070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Q, Ye C, McCrimmon RJ, Dhillon H, Choi B, Kramer MD, Yu J, Yang Z, Christiansen LM, Lee CE, Choi CS, Zig-man JM, Shulman GI, Sherwin RS, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB. Synaptic glutamate release by ventromedial hypothalamic neurons is part of the neurocircuitry that prevents hypoglycemia. Cell Metab. 2007;5:383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallen-Mackenzie A, Gezelius H, Thoby-Brisson M, Nygard A, Enjin A, Fujiyama F, Fortin G, Kullander K. Vesicular glu-tamate transporter 2 is required for central respiratory rhythm generation but not for locomotor central pattern generation. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:12294–12307. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3855-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Peca J, Matsuzaki M, Matsuzaki K, Noguchi J, Qiu L, Wang D, Zhang F, Boyden E, Deisseroth K, Kasai H, Hall WC, Feng G, Augustine GJ. High-speed mapping of synaptic connectivity using photostimulation in channelrhodopsin-2 transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8143–8148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700384104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]