Abstract

Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is characterized by left ventricular hypertrophy and myofibrillar disarray, and often results in sudden cardiac death. Two HCM mutations, N47K and R58Q, are located in the myosin regulatory light chain (RLC). The RLC mechanically stabilizes the myosin lever arm, which is crucial to myosin’s ability to transmit contractile force. The N47K and R58Q mutations have previously been shown to reduce actin filament velocity under load, stemming from a more compliant lever arm (Greenberg, 2010). In contrast, RLC phosphorylation was shown to impart stiffness to the myosin lever arm (Greenberg, 2009). We hypothesized that phosphorylation of the mutant HCM-RLC may mitigate distinct mutation-induced structural and functional abnormalities. In vitro motility assays were utilized to investigate the effects of RLC phosphorylation on the HCM-RLC mutant phenotype in the presence of an α-actinin frictional load. Porcine cardiac β-myosin was depleted of its native RLC and reconstituted with mutant or wild-type human RLC in phosphorylated or non-phosphorylated form. Consistent with previous findings, in the presence of load, myosin bearing the HCM mutations reduced actin sliding velocity compared to WT resulting in 31–41% reductions in force production. Myosin containing phosphorylated RLC (WT or mutant) increased sliding velocity and also restored mutant myosin force production to near WT unphosphorylated values. These results point to RLC phosphorylation as a general mechanism to increase force production of the individual myosin motor and as a potential target to ameliorate the HCM-induced phenotype at the molecular level.

Keywords: Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Regulatory light chain phosphorylation, Cardiac ventricular myosin, Load dependence

1. Introduction

Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most common type of genetic heart disease in United States [11]. The condition is characterized by ventricular hypertrophy and myofibrillar disarray. While many patients with HCM are symptom-free, the disease often clinically manifests as progressive heart failure or sudden cardiac death [11,44]. HCM is caused by single autosomal dominant mutations in genes that encode for cardiac sarcomeric proteins, including MYL2 encoding the ventricular regulatory light chain (RLC) of myosin [35].

The muscle sarcomere consists of an interdigitating array of thick, myosin containing filaments and thin, actin containing filaments. Muscle contraction results from the relative sliding of thick and thin filaments driven by the ATP dependent interaction of myosin crossbridges with the thin filament in which contractile force is transmitted from the actin-bound head to the thick filament backbone. Small conformational changes in the myosin catalytic domain are amplified by the neck region which acts as a lever arm to produce myosin-based force and motion generation [23,49]. The RLC provides mechanical stability and imparts stiffness to the lever arm by binding to the myosin heavy chain (MHC) neck α-helix at the S1–S2 junction.

Two HCM mutations, N47K and R58Q, are located in the N-terminal region of the RLC in close proximity to the cation binding site and the phosphorylation site. N47K is associated with late onset, rapidly progressing mid-ventricular hypertrophy, and R58Q is associated with an early onset left ventricular hypertrophy and sudden cardiac death [4,20,35]. In vitro motility assays, using porcine cardiac (PC) myosin, where the native RLC was exchanged with human ventricular RLC containing the N47K and R58Q mutations, showed reduced force production of the myosin motor [15] suggesting that altered neck domain structure and reduced neck domain stiffness underlies the mutation-induced contractile deficit.

Mouse RLC has been shown to be doubly phosphorylated on serine 14 and serine 15, however, the human ventricular RLC isoform contains a single highly conserved phosphorylation site at serine 15 [37] that serves a crucial role in myosin mechanics and kinetics by positioning heads closer to actin as well as increasing the stiffness of the neck domain [13]. In cardiac muscle fibers, isometric force production increased with increasing levels of RLC phosphorylation during fiber shortening [45]. Interplay between cardiac myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) and a myosin phosphatase holoenzyme in human ventricular tissue is thought to maintain the level of RLC phosphorylation at about ~40% [5,25,30]. However, zipper interacting protein kinase has also been shown to phosphorylate RLC on serine 15 in vitro and in vivo [6], adding to the complexity of RLC phosphorylation regulation. Decreased levels of RLC phosphorylation lead to cardiac pathology, while increased levels of RLC phosphorylation have been shown to attenuate hypertrophy and protect against cardiac dysfunction [48]. Several HCM-linked RLC mutations are spatially located in close proximity to the RLC phosphorylation site and phosphorylation of the RLC has been shown to reverse some of mutationinduced biochemical and structural alterations of the isolated RLC [42,43].

The contrasting effects of the HCM mutations and phosphorylation of the RLC on myosin stiffness and force production suggest that phosphorylation-induced increases in cardiac myosin force production could compensate for N47K- and R58Q-induced reductions in myosin force generation. To gain insight into the molecular mechanism of RLC phosphorylation and study its effect on the HCM RLC mutant phenotype, we use in vitro motility assays to measure the force production of myosins bearing mutant (N47K and R58Q) and wild-type (WT) human ventricular regulatory light chains (hvRLCs). Mammalian hearts express two MHC isoforms (α and β). The human heart is comprised predominantly of the β-MHC (>90% in left ventricle), and undergoes a shift in isoform expression to nearly 100% β-MHC in failing hearts [22]. We therefore studied porcine cardiac β-myosin that has its native RLC replaced with hvRLC via loaded motility assay [14]. Upon MLCK-induced phosphorylation of the RLC, we see increased actin sliding velocity for both mutant and WT myosins at all loads measured, indicating an increase in force production. This suggests a general mechanism at the molecular level by which RLC phosphorylation enhances the force output of the cardiac myosin motor in health and disease.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Protein purification and expression

2.1.1. Porcine cardiac myosin

Porcine cardiac myosin was isolated as described by Pant et al. [31]. The left ventricle is removed from porcine hearts, and minced on ice. The minced tissue is ground, and 50–100 g of tissue is homogenized in 100–200 ml of Extraction Buffer (0.3 M KCl, 15 mM KPi, 20 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 3.3 mM ATP, pH 6.7). The homogenate is diluted 4-fold with cold H2O and filtered through cheesecloth. The solution is then diluted 10-fold with cold H2O and allowed to precipitate for 4 h at 4 °C. The precipitate is collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 1 M KCl, 60 mM KPi, 20 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, pH 6.7, then dialyzed overnight against 0.6 M KCl, 25 mM KPi, 5 mM DTT, pH 6.7 at 4 °C. The solution is diluted with an equal volume of cold H2O, stirred for 30 min at 4 °C, and centrifuged at 41,000g for 1 h to remove insoluble actin. Following 10-fold dilution with cold H2O the supernatant is allowed to precipitate for 4 h at 4 °C. The precipitate is collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 3 M KCl, 50 mM KPi, 5 mM DTT, pH 6.7, then dialyzed overnight against 0.6 M KCl, 50 mM KPi, 5 mM DTT, pH 7 at 4 °C followed by clarification by centrifugation at 41,000g for 1 h and the supernatant is collected. PC myosin is stored in 50% glycerol until needed for experiments.

2.1.2. Chicken skeletal actin

Unlabeled actin was prepared from chicken pectoralis muscle acetone powder, as previously described [39]. The actin was suspended in actin buffer (25 mM KCl, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM DTT, 25 mM imidazole, 4 mM MgCl2). TRITC phalloidin-labeled actin was prepared by reacting a 1:1 M ratio mixture of TRITC phalloidin and actin in actin buffer overnight at 4 °C.

2.1.3. Chicken smooth muscle MLCK

Myosin light chain kinase was isolated from chicken gizzards as previously described [29], with the following modifications. Supernatant containing extracted MLCK was clarified via centrifugation at 250,000g for 45 min at 4 °C before being loaded onto a DEAE-Sepharose column. DEAE resin equilibrated with DEAE loading buffer (40 mM Tris–HCl, 20 mM NaCl, 25 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.5), was added to the supernatant fraction, and the slurry was mixed overnight at 4 °C. The batch bound resin was loaded onto the DEAE-Sepharose column equilibrated in DEAE loading buffer. The enzyme was eluted with a linear gradient from 20 to 300 mM NaCl in the same buffer. Protein fractions containing the kinase were determined by SDS–PAGE, and then pooled. Following overnight dialysis of the pooled fractions, the kinase enriched fractions were centrifuged at 300,000g for 10 min at 4 °C before being loaded onto an Affi-Gel Blue column. Pooled fractions were dialyzed overnight against a buffer containing 25 mM MOPS, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.5. MLCK was mixed 1:1 with glycerol and stored at −20 °C until needed for experiments.

2.1.4. Human ventricular RLC

The cDNA for wild-type (WT) and mutant (N47K and R58Q) hvRLCs were cloned into the pET-3d (Novagen) plasmid vector, transformed into BL21 expression host cells, and expressed proteins were purified as described previously [43].

2.2. RLC phosphorylation and exchange

Human recombinant RLC (WT, N47K or R58Q) was phosphorylated with 0.25 µM MLCK and 1 µM Calmodulin in a buffer containing 20 mM MOPS, 30 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM PMSF, pH 7.3, 5 mM DTT. MLCK, calmodulin and calcium were pre-mixed and the reaction was initiated by the addition of ATP to a final concentration of 5 mM. The reaction was performed at room temperature for 1 h, then placed on ice. RLCs were dissolved in 8 M urea sample buffer and run on a 10% polyacrylamide gel containing 8 M urea to determine the extent of RLC phosphorylation.

Endogenous RLC was depleted from PC myosin and bacterially expressed hvRLCs were reconstituted onto RLC depleted PC myosin. Myosin (2 mg/ml) was treated with 0.8% Triton X-100 and 15 mM (1,2-diaminocyclohexanetetraacetic acid) CDTA, in a buffer containing 0.5 M KCl, 10 mM KPi, pH 8.5, for 15 min at room temp with slow stirring. The solution was precipitated with 10 volumes of cold distilled water containing 10 mM DTT and collected by centrifugation. Myosin depleted of endogenous RLC was then resuspended in a buffer composed of 0.4 M KCl, 50 mM MOPS, pH 7, 2 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT and mixed in a 1:3 M ratio (depleted myosin: RLC) with recombinant hvRLC (WT, N47K, or R58Q) and incubated at 4 °C for 2 h with slow stirring. RLC-reconstituted myosin was dialyzed in 5 mM DTT and collected by centrifugation. Myosin pellets were resuspended in myosin buffer composed of 0.3 M KCl, 25 mM (N,N-Bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid) BES, pH 7.4, and 1 mM EGTA, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, then mixed 1:1 with glycerol and stored at −20 °C until needed for experiments. PC myosin, RLC depleted myosin and RLC exchanged myosins were analyzed for levels of RLC exchange via 12% SDS–PAGE.

2.3. Actin-activated ATPase assay

To determine myosin ATPase activity the rate of Pi production was measured by monitoring solution absorbance at 360 nm. Using the ELIPA kit (Enzyme Linked Inorganic Phosphate Assay) (Cytoskeleton, cat# BK051), myosin enzymatic activity is coupled to the catalytic conversion of 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methylpurine ribonucleoside (MESG) to 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methylpurine by purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP), resulting in an absorbance shift from 330 to 360 nm. One molecule of Pi produces one molecule of 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methylpurine in an essentially irreversible reaction. Myosin at 0.1 µM was mixed with 1 µM actin in a buffer containing 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 15 mM PIPES, pH 7.1, 0.5 mM DTT, and the reaction was initiated by the addition of 1 mM ATP. Solution absorbance was measured using a Biomate 3 Spectrophotometer, with readings taken every 30 s for 20 min. The change in absorbance over time was fit to a linear regression, and the ATPase rate was determined by the slope of the trendline.

2.4. In vitro motility assays

To determine mutant myosin force generation we employed the frictional loading assay where a non-motor, low affinity actin-binding protein is used as a mechanical load in a standard in vitro motility assay. For these experiments a nitrocellulose coated cover slip was attached to a glass microscope slide with double stick tape. Experimental solutions were added to the resulting flow chamber. First, myosin in high-salt buffer (300 mM KCl, 25 mM BES, 5 mM EGTA, 4 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT) was mixed with 1 mM ATP and 1.1 µM actin and centrifuged in an Airfuge for 25 min at 100,000×g. Damaged myosin heads that are unable to bind and release from actin are removed from the supernatant. 100 µg/ml of myosin was mixed with varying concentrations of α-actinin in high-salt buffer and added to the flow chamber. After incubation for 1 min, the myosin and α-actinin are bound to the coverslip surface. The chamber was then washed with 30 µl of 1 mg/ml BSA in high-salt buffer to fill any remaining gaps on the coverslip surface. After 1 min BSA incubation, the chamber was washed with 60 µl of low-salt buffer (55 mM KCl, 25 mM BES, 5 mM EGTA, 4 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT). To remove any inactive myosin, 1 µM unlabeled actin was added in low-salt buffer and allowed to bind to the myosin for 2 min. The chamber was washed with 2 volumes of low-salt buffer containing 1 mM ATP, followed by 4 volumes of low-salt buffer with no ATP. TRITC-labeled actin filaments (~10 nM) in low-salt buffer were then added and allowed to bind to the myosin in the absence of ATP. The movement of actin was initiated by the addition of 1 mM ATP in low-salt buffer with oxygen scavengers (17 units/ml glucose oxidase and 125 units/ml catalase) and 0.5% methylcellulose. Filament movement was observed at 30 °C with an intensified charge-coupled device camera (IC300; PTI, Birmingham, NJ, USA). Video images were captured at 1–5 s intervals using a PIXCI® EL1 frame grabber and XCAP software (Epix, Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL, USA), and 2 or more movies per flow cell were analyzed.

2.5. Curve fitting

In the absence of an exogenously added load, the myosin driving force (Fd) propels actin at maximal velocity (Vmax). In the frictional loading motility assay, α-actinin provides an exogenous load (Ffric) to the actin filament that opposes the myosin driving force. Actin sliding velocity (V) is determined by the balance of the forces acting on the actin filament:

| (1) |

The frictional load exerted by α-actinin (α) in the motility assay is given by Eq. (2):

| (2) |

where κ is the system compliance associated with the α-actinin and the α-actinin linkages, L is the length of a typical actin filament, r is the reach of an α-actinin to bind to an actin filament, kA is the second-order rate constant for α-actinin attachment to actin, kD is the α-actinin detachment rate, and ζ and χ are constants that define the surface geometry of α-actinin on the surface.

A model describing actin sliding velocity (V) dependence on α-actinin concentration ([α]) is determined by substituting Eq. (2) into Eq. (1). This model was fit to the data obtained from frictional loading assays according to Eq. (3):

| (3) |

The model is fit to the data using a nonlinear least-squares algorithm (SigmaPlot; Systat Software). Maximal sliding velocity (Vmax) and myosin force production (Fd) are derived from the fit to the data. The derivation of Eqs. (2) and (3), values used for model fitting, and an explanation of model limitations are provided in Greenberg and Moore (2010) [14].

Data from frictional loading motility assays was transformed to represent myosin power output as a function of frictional load. Force–velocity data was obtained by converting [α-actinin] to force using Eq. (2). Power values were subsequently calculated by taking the product of force and velocity, and plotted versus the force axis. Power curves were constructed by fitting the force-power data (Fload, P) to the empirically derived Hill equation for power given by [16]:

| (4) |

where Fo is the isometric force and a and b are constants. Average force values (Fd) determined from Eq. (3) were used to constrain the model fits to the data. The equation was fit to the data using a nonlinear least-squares algorithm (SigmaPlot; Systat Software). The load at which maximal power output occurs was calculated by setting the derivative of the Hill power equation equal to zero and solving for Fload. This value was substituted into Eq. (4) to determine maximal power output. Errors in these parameters were determined from the errors in the least squares fit of Eq. (4).

2.6. Statistics

Actin filaments were tracked for 10–30 consecutive video frames using the MTrackJ plugin in ImageJ. For each flow cell, the average actin velocity was determined from 25–30 actin filaments. This average velocity and its associated α-actinin concentration represents one data point in an experiment. RLC depletion and reconstitution was performed on at least three different PC myosin preparations, and an experimental data set was obtained for each preparation. An average data set was obtained by taking the weighted average of the velocities from all data sets (based on the number of filaments analyzed per [α-actinin] in the individual experiments). Average data sets are plotted in Fig. 2 and fit to Eq. (1) to determine the average force (Fd) of the bed of myosin. Significance between force values was determined using the standard errors of the regression coefficients in the fits of the data to the model curve. For comparisons between two groups (i.e. dephosphorylated and phosphorylated RLC) the t value was determined by calculating the pooled variance from regression coefficient parameters (for measurements of Fd) or from the mean and variance of the data (for measurements of ATPase and Vmax), and a p value was obtained using the student’s t test distribution. One-way ANOVA was used for comparisons between three or more groups.

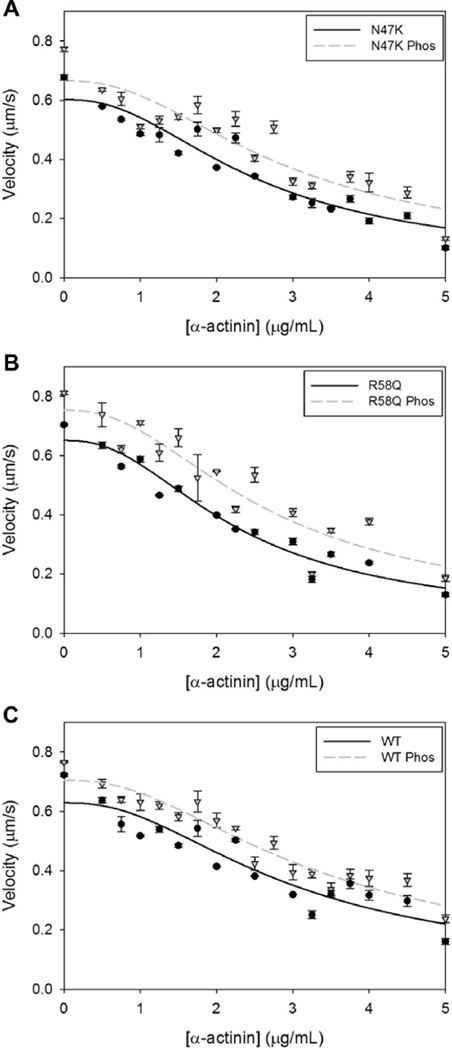

Fig. 2.

Frictional loading assays measure the force production of a bed of myosins. Average actin filament sliding velocity and SEs of the average sliding velocity are plotted as a function of α-actinin added to the motility assay surface. Average actin sliding velocity is determined from a minimum of 3 experiments. Plots are shown for myosins bearing RLCs in the dephosphorylated (circles, solid line) and phosphorylated (triangles, dashed line) states for (A) N47K, (B) R58Q, and (C) WT RLCs.

3. Results

3.1. RLC phosphorylation, depletion and reconstitution

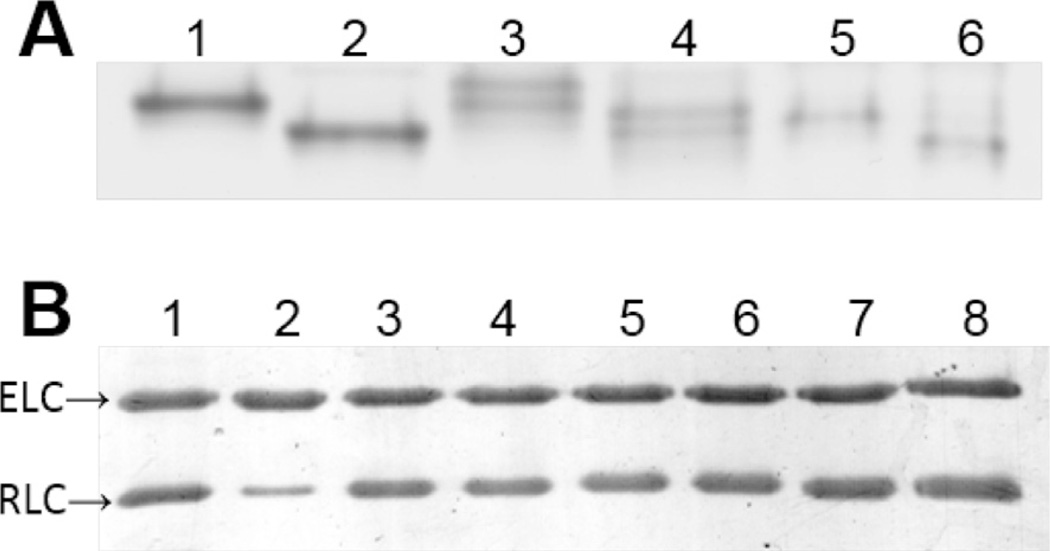

Myosin was purified from the left ventricles of porcine hearts for studies using β-MHC, which is 98% identical to human β-MHC [7,19]. WT, N47K and R58Q hvRLC was phosphorylated by smooth muscle MLCK before reconstitution onto the β-MHC. A minimum of three myosin preparations and subsequent RLC exchange procedures were performed for the studies carried out in this research. Levels of RLC phosphorylation, depletion and reconstitution were determined by densitometry. As shown in Fig. 1, WT and N47K light chains were readily phosphorylated (95.7 ± 3.6% and 98.4 ± 1.6%) as indicated by increased mobility toward a more acidic isoelectric point in Urea PAGE, which is consistent with phosphorylation (Fig. 1a). Full phosphorylation was never accomplished with R58Q light chains (87.4 ± 0.8%), while mock reactions showed no evidence of phosphorylation. Native PC RLC was 84.8 ± 5.8% depleted, and MHCs were fully reconstituted with expressed mutant and WT hvRLC that were either phosphorylated or underwent a mock phosphorylation reaction in the absence of exogenously added MLCK (Fig. 1b: WT, 107.5 + 5.3%; WT Phos, 108.6 + 9.6%; N47K, 106.2 + 9.8%; N47K Phos 96.2 + 8.9%; R58Q 97.8 + 15.7%; R58Q Phos, 106.6 + 14.1%).

Fig. 1.

Gel electrophoresis of RLC phosphorylation and exchange reactions. (A) Charge separation of dephosphorylated and phosphorylated bacterially expressed human ventricular RLCs is shown on an 8 M urea 10% polyacrylamide gel. Due to a more acidic isoelectric point phosphorylated RLCs migrate further than their respective dephosphorylated counterparts. WT RLC (lane 1), WT Phos RLC (lane 2), N47K RLC (lane 3), N47K Phos RLC (lane 4), R58Q RLC (lane 5), R58Q Phos RLC (lane 6). (B) SDS–PAGE of PC myosin RLC exchange reaction shows ELC and RLC bands from PC myosin (lane 1), PC RLC depleted myosin (lane 2; 85% depletion), and PC RLC depleted myosin fully reconstituted with hvRLCs (lanes 3–8), same order as panel A.

The N47K RLC migrated as a double band in urea-PAGE for mock and MLCK-treated preparations, but as a single band in SDS–PAGE (Fig. 1) indicating the existence of charge variants of the N47K RLC. There was no evidence of RLC degradation when analyzed with 15% SDS–PAGE (data not shown). Both charge variants were consistently phosphorylated. The charge variants may arise from acetylation of the lysine residue introduced by the mutation, or from deamidation of asparagine residues that flank the phosphorylation site at serine 15 [37]. Both processes are known to occur in bacterial expression systems.

3.2. Unloaded measurements of myosin enzymatic activity and motility

The actin-activated ATPase activity of WT and mutant myosin was determined by monitoring absorbance of a solution containing 0.1 µM myosin, 1 µM actin, and 1 mM ATP. Absorbance at 360 nm is directly proportional to the amount of Pi generated in the solution. There was no significant difference in ATPase activity between any myosins (Table 1). The ATPase rate is directly proportional to the maximal sliding velocity (Vmax) of actin in the motility assay. Myosin will move actin at maximal velocity when there is no load opposing the myosin powerstroke. The only significant difference in Vmax was between myosins bearing R58Q RLC in the dephosphorylated and phosphorylated states. Comparisons of Vmax values between all other myosins were not significantly different (Table 1).

Table 1.

Unloaded measurements of myosin actin-activated ATPase and actin sliding velocity.

| WT | WT Phos | N47K | N47K Phos | R58Q | R58Q Phos | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATPase (min−1) | 7.067 ± 1.241 | 6.500 ± 0.836 | 6.375 ± 0.897 | 8.667 ± 1.304 | 5.700 ± 0.634 | 6.775 ± 0.844 |

| Vmax (µm/s) | 0.731 ± 0.020 | 0.781 ± 0.021 | 0.677 ± 0.049 | 0.773 ± 0.045 | 0.704* ± 0.027 | 0.800* ± 0.027 |

ATPase (n = 3–4) and Vmax (n = 4–8) values are given as the mean ± SEM. Vmax values shown are from the observed velocities with no α-actinin present on the coverslip surface, not derived from the fit of Eq. (3). There is no significant difference between WT and mutant myosin, or between dephosphorylated and phosphorylated myosin pairs for the unloaded measurements, except for the maximal sliding velocity of myosin bearing R58Q RLCs with and without phosphorylation (*).

3.3. RLC phosphorylation increases myosin force production

To determine mutant and WT myosin force generation with and without phosphorylation we employed a frictional loading assay where a non-motor, actin-binding protein is used as a mechanical load in the standard in vitro motility assay [14]. Actin filament mobility is reduced in the presence of α-actinin, a protein that weakly and transiently binds to actin. As α-actinin surface concentration increases, actin filaments experience a greater oppositional force to the myosin driving force, and actin sliding velocity decreases (Fig. 2). Thus, the myosin driving force can be estimated by modeling the relationship between the α-actinin concentration and actin sliding velocity [14]. In the absence of load, the N47K and R58Q myosins propelled actin at a similar velocity as WT myosin. However, in the presence of α-actinin-induced frictional load, N47K and R58Q mutant myosins moved actin at slower velocities than WT myosin (Fig. 2). This resulted in significantly decreased force production for both mutations (31% and 41% for N47K and R58Q) that is consistent with previous results [12]. Upon phosphorylation, all myosins show an increase in actin velocity at any given α-actinin concentration (Fig. 2a–c), resulting in significantly higher force production for myosins bearing a phosphorylated RLC. Phosphorylation-based increases in force were observed for each individual experimental preparation as well as for the average (Fig. 3). The phosphorylation induced increase in force production restored both mutations to WT dephosphorylated force levels.

Fig. 3.

Average force values of cardiac β-myosins. Force values and SE are determined from the fit of the average data to Eq. (1). N47K and R58Q mutant myosins display significantly reduced force production (p < 0.05, 0.02, respectively) compared to WT myosin force values (dotted line). Phosphorylation of WT, N47K and R58Q myosins results in significantly increased force production (p < 0.03, 0.05, 0.03, respectively). When compared to WT phosphorylated myosin, N47K phosphorylated myosin exhibited borderline significance (p = 0.0502) and R58Q phosphorylated myosin was significantly different (p < 0.02).

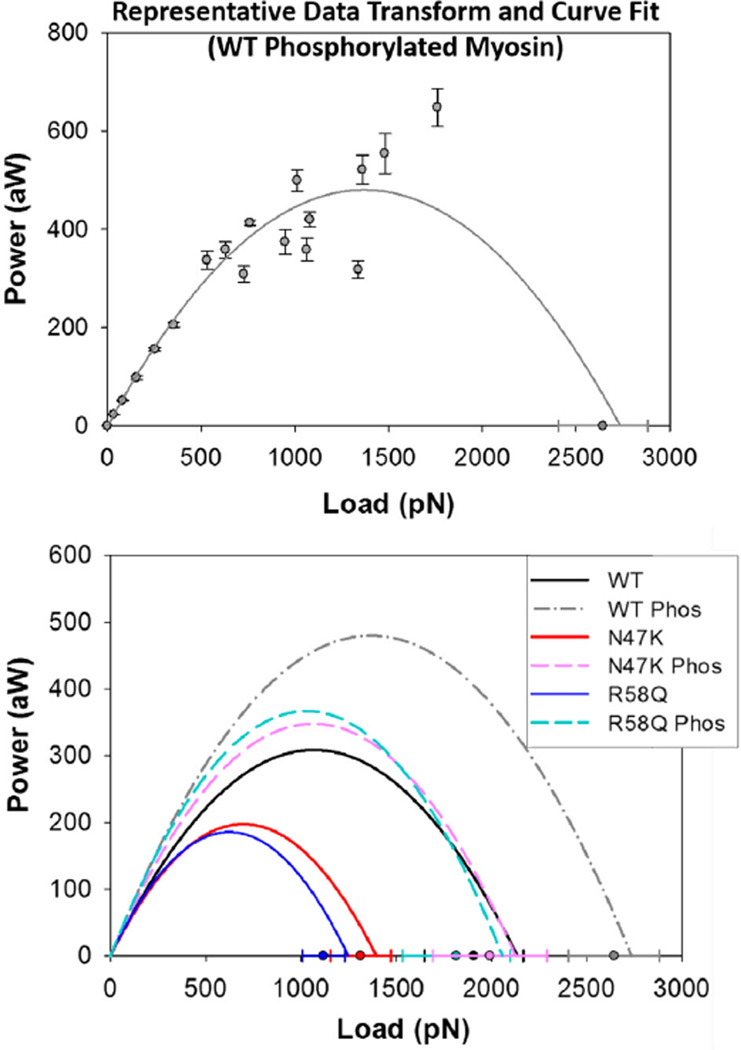

3.4. Phosphorylation increases power output

To determine how power is affected by the mutant phenotype, α-actinin concentrations were converted to frictional force values according to Eq. (2) (see Section 2) allowing for the construction of force-power relationships. Power output of phosphorylated WT, N47K, and R58Q myosins (dashed lines) are compared to mock phosphorylation reaction controls (solid lines) in Fig. 4. Compared to WT, both N47K- and R58Q-mutant myosins show reductions in peak power and the load at which maximal power occurs. Phosphorylation by MLCK increased power output of all myosins tested (Fig. 4). Values of maximal power output and the load at which maximal power output occurs were determined from the power curves shown in Fig. 4. Parameters from the fit are summarized in Table 2.

Fig. 4.

Power output of cardiac β-myosins. (Top panel) Power is derived by converting α-actinin concentration in the frictional loading assays to a frictional force using Eq. (2), and then taking the product of force and velocity. Power curves are generated by fitting the force-power data to the empirically derived Hill equation (Eq. (4)). Shown is a representative fit of the Hill Power Equation to transformed data for WT phosphorylated myosin. (Bottom panel) Power output curves are shown in the absence of transformed data for better visualization and comparison of power trends. Isometric force values (±SE) estimated from frictional loading motility assays are used to constrain the fit and are shown on the x-axis. Cardiac myosins bearing hvRLCs in the phosphorylated state (dashed lines) show increased power output compared to hvRLCs in the dephosphorylated states (solid lines).

Table 2.

Loaded parameters of cardiac beta-myosin predicted from model fitting.

| WT | WT Phos | N47K | N47K Phos | R58Q | R58Q Phos | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max power (aW) | 309 ± 93 | 480 ± 81 | 198 ± 57 | 348 ± 95 | 186 ± 53 | 367 ± 117 |

| LoadM. power (pN) | 1069 ± 112 | 1368 ± 72 | 698 ± 63 | 1063 ± 122 | 624 ± 51 | 1029 ± 134 |

| Fo (pN) | 2137 ± 224 | 2736 ± 143 | 1396 ± 126 | 2126 ± 244 | 1248 ± 102 | 2058 ± 268 |

Parameters ± SE from least squares fitting of loaded motility assay data. Maximal power, load at maximal power and Fo were determined from the model fits of Eq. (4).

4. Discussion

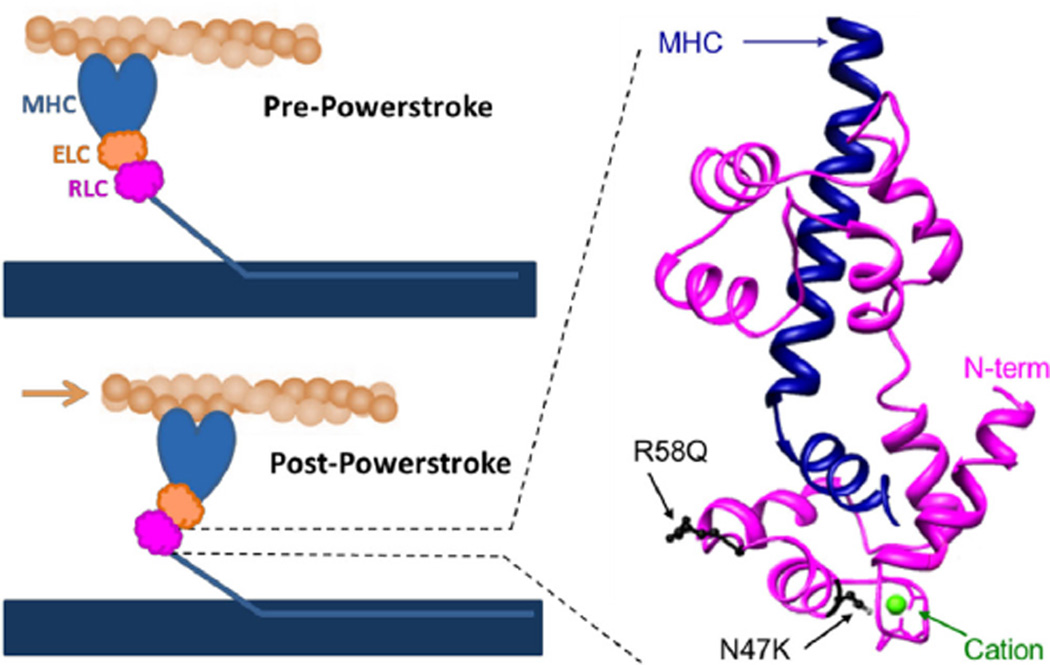

This study examined the effects of phosphorylation of the myosin regulatory light chain (RLC) on wild-type myosin as well as the ability of phosphorylation to restore decreases in force generation observed for myosins containing HCM-linked mutations located near the cationic binding site of the RLC (Fig. 5). We show using loaded in vitro motility assays that phosphorylation enhances myosin contractility for all myosins studied. Furthermore, we show that phosphorylation of both N47K and R58Q myosins restore mutation-induced decreases in force production to near wild-type dephosphorylated myosin levels.

Fig. 5.

Regulatory light chain binds the myosin heavy chain (MHC) at hinge region. (Left) During the powerstroke actin (tan filament) is displaced by the myosin crossbridge which is tethered to the thick filament (blue horizontal rectangle). The myosin lever arm is stabilized by the essential light chain (ELC) and regulatory light chain (RLC), and undergoes a ~70° angle swing from the pre-powerstroke state to the post-powerstroke state. The ability of myosin generate the powerstroke against load will depend on the stiffness of the myosin light chain binding domain. (Right) A three-dimensional representation of the RLC (magenta) wrapping around the MHC (blue) at a lever arm hinge region illustrates positions of HCM mutations (black) and the cation binding site (green) within the RLC. The first 18 residues of the RLC N-terminus are missing from the structure and therefore the RLC phosphorylation site at Ser15 is not shown. The RLC structure is modified from the crystal structure of Rayment et al., 1993 (PDB: 2MYS). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The RLC binds directly to the elongated α-helical neck region of myosin. This stabilization allows for the transmission of force from the myosin active site down the lever arm. Previously we proposed that N47K and R58Q mutations disrupt the sensitivity of myosin to load by changing the structure and mechanical properties of the α-helical neck region of myosin. The portion of the RLC containing the phosphorylation site at serine 15 is not defined in the existing atomic structure of the RLC bound to the heavy chain (Fig. 5) thus there is no evidence for a direct interaction between the regions of the RLC containing the mutations and serine 15. However, phosphorylation of the RLC has been shown to restore N47K- and R58Q-induced structural changes and disruptions of calcium binding, indicating a functional interaction [42,43] suggesting structural rearrangements of the RLC in response to phosphorylation.

Increases in the Ca2+ sensitivity of ATPase and force were seen in porcine cardiac fibers reconstituted with N47K and R58Q RLC [42], while prolonged Ca2+ transients were observed in transgenic mouse fibers bearing these RLC mutations [47]. In addition, measurements of skinned papillary muscle fibers from R58Q transgenic mice demonstrated prolonged force transients accompanied by a significant decrease in the maximal force production [47], consistent with the decrease in force production seen in this work. The more severe phenotype of R58Q also occurs at the clinical level and presents at a much earlier stage in life [20]. It is possible that the severe phenotype associated with the R58Q mutation stems from decreases in the levels of RLC phosphorylation associated with the R58Q mutation [1]. Here we show that phosphorylation of WT or mutant RLC increases force, suggesting an enhancement of myosin neck domain stiffness. Furthermore, it has been shown that phosphorylation of the mutant light chains can restore calcium binding to the R58Q recombinant RLC [43]. Thus phosphorylation-induced structural changes of the RLC likely affect its interactions with the myosin neck region and underlie the ability of phosphorylation to enhance myosin force and velocity under load, and restore these parameters of the mutant myosins to near WT levels.

The power output of the heart is equal to the rate at which the heart produces work, and is an important parameter that represents the ability of the heart to efficiently pump blood [2,3,24,38]. Power is calculated as the product of force and velocity. Here we used the frictional load induced by α-actinin in the in vitro motility assay to provide information about the load velocity relationship for the interaction of myosin with actin. Compared to WT myosin, both N47K and R58Q mutant myosins reduced actin velocity at increasing loads, indicative of a reduction in myosin power output. Reduction of actomyosin power (Fig. 4) is expected to impair the ability of the heart to eject blood. Similarly, a mismatch in the power output of the HCM heart and the power needed to overcome afterload would reduce the ability of the heart to contract against the arterial blood pressure and would ultimately reduce cardiac output. Consistent with this idea, measurements on isolated perfused working hearts from transgenic mice bearing the N47K and R58Q mutations resulted in decreased cardiac output and power [1]. In addition, the R58Q transgenic hearts consumed more oxygen suggesting that alterations in the load–power relationship can result in diminished energetic efficiency [1].

In contrast to HCM mutations, RLC phosphorylation increased actin velocity across all loads for WT and mutant myosin. Given that the entire load velocity relationship is shifted to greater values, it is not surprising that power output of the individual myosin motor was increased upon phosphorylation. Studies utilizing porcine cardiac fibers showed that increased RLC phosphorylation levels lead to an increase in force and power output during fiber shortening at physiologically relevant loads [45]. A phosphorylation induced increase in the maximum power of isolated myosin shown in this work is likely a contributing factor to this phenomenon.

The physiological state of the heart is highly dependent on RLC phosphorylation but its specific role in cardiac muscle contraction remains elusive. Increases in RLC phosphorylation have been observed with treadmill exercise training in rats [10], while transgenic mice that expressed nonphosphorylatable RLC directly showed that RLC phosphorylation is critical to the proper functioning of the heart [36]. In addition, RLC dephosphorylation has been shown to correlate with cardiac failure [1,25] and hypertrophy [9,18], while phosphorylation was shown to attenuate the hypertrophic response [17,48]. At the cellular level, phosphorylation of RLC has been correlated with increased Ca2+ sensitivity to force [36,41], and an increased rate of force development [26,40]. These phenomenon were shown to correlate with a phosphorylation induced disposition of myosin heads away from the thick filament backbone and decrease in the myofibrillar lattice spacing [8].

The molecular mechanism underlying the effects of RLC phosphorylation on cardiac muscle contraction has not been fully elucidated. It is likely that RLC phosphorylation affects the mechanical properties of the myosin motor as well as ensemble properties through interactions with the thick filament backbone. Measurements of isolated skeletal muscle myosin suggests that myosin with phosphorylated RLC shows a greater sensitivity to load when compared to dephosphorylated myosin presumably due to an increase in neck domain stiffness [13]. Consistent with this notion, a recent study by Wang et al. demonstrated that phosphorylation of the RLC results in a shift to larger step sizes for cardiac β-myosin [46]. The increase in force production of cardiac myosin seen here (Fig. 3) is in agreement with a phosphorylation induced increase in lever arm stiffness which would tend to increase the unitary and ensemble force of myosin (Fig. 5).

Studies performed on another RLC HCM mutation, D166V, have also targeted RLC phosphorylation as a rescue mechanism of a mutation induced detrimental phenotype [27,28]. In the tertiary structure of myosin RLC, the D166V mutation is predicted to be in close proximity to the RLC phosphorylation site [32]. Similar to R58Q, the D166V mutation resulted in decreased levels of RLC phosphorylation which likely contributed to decreased force production in skinned papillary muscle fibers from transgenic D166V mice [21,27] and the malignant phenotype in humans [33,34]. In the studies carried out by Muthu et al., a phosphomimetic S15D was incorporated into the RLC [28]. This pseudo– phosphorylation restored force production of the D166V myosin in the in vitro motility assay, similar to the rescue by RLC phosphorylation seen in this work. Similar results with phosphomimetic and actual MLCK-induced phosphorylation of the RLC suggests that it is the addition of a negatively charged residue that is responsible for the reversal of mutation induced effects and that the substitution of Ser15 with Asp appropriately mimics the addition of phosphate.

Here we studied the effects of RLC phosphorylation on disease-linked mutant and WT myosins in the presence of a frictional load imposed by the non-motor actin binding protein α-actinin. By modeling the frictional load due to α-actinin, force–velocity relationships for isolated mutant and WT actomyosin were obtained. We found that phosphorylation increased the isometric force of WT and mutant β-cardiac myosin. Furthermore, observed velocities were increased across all loads indicating an increase in myosin power output upon RLC phosphorylation. These phosphorylation-induced shifts restored mutation-based reductions in maximal force output to WT levels. An increase in velocity under load is functionally significant since the heart typically operates against a load imposed by diastolic blood pressure. By introducing a mismatch between the maximal oscillatory work capacity of the heart and the heart afterload, the N47K and R58Q mutations would tend to reduce the cardiac output under physiologically relevant loads, placing additional energetic restrains on the myosin. A shift toward higher power and higher loads for peak power may be accomplished via RLC phosphorylation. It is intriguing to consider phosphorylation as a drug target for alleviating symptoms in patients with RLC HCM mutations that exhibit reduced force generation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Priya Muthu for her expert help with experiments and insightful discussions. This work was supported by American Heart Association Grant 12PRE11910009 (AK), and National Institutes of Health Grants NIH- HL071778 & HL108343 (DSC) and HL077280 (JM).

Glossary

- HCM

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- RLC

regulatory light chain (gene MYL2)

- β-MHC

beta-myosin heavy chain (gene MYH7)

- PC

porcine cardiac

- WT

wild-type

- hvRLC

human ventricular regulatory light chain

- ELC

essential light chain

- MLCK

myosin light chain kinase

Footnotes

Transparency Document

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found in the online version.

References

- 1.Abraham TP, et al. Diastolic dysfunction in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy transgenic model mice. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009;82(1):84–92. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alpert NR, et al. Molecular mechanics of mouse cardiac myosin isoforms. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002;283(4):H1446–H1454. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00274.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alpert NR, et al. Molecular and phenotypic effects of heterozygous, homozygous, and compound heterozygote myosin heavy-chain mutations. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005;288(3):H1097–H1102. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00650.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen PS, et al. Myosin light chain mutations in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: phenotypic presentation and frequency in Danish and South African populations. J. Med. Genet. 2001;38(12):E43. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.12.e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan JY, et al. Identification of cardiac-specific myosin light chain kinase. Circ. Res. 2008;102(5):571–580. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang AN, et al. Cardiac myosin is a substrate for zipper-interacting protein kinase (ZIPK) J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285(8):5122–5126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.076489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang KC, Fernandes K, Goldspink G. In vivo expression and molecular characterization of the porcine slow-myosin heavy chain. J. Cell Sci. 1993;106(Pt 1):331–341. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.1.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colson BA, et al. Differential roles of regulatory light chain and myosin binding protein-C phosphorylations in the modulation of cardiac force development. J. Physiol. 2010;588(Pt 6):981–993. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.183897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding P, et al. Cardiac myosin light chain kinase is necessary for myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation and cardiac performance in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285(52):40819–40829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.160499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzsimons DP, et al. Left ventricular functional capacity in the endurancetrained rodent. J. Appl. Physiol. 1990;69(1):305–312. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.1.305. (1985) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frey N, Luedde M, Katus HA. Mechanisms of disease: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2012;9(2):91–100. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenberg MJ, et al. Cardiomyopathy-linked myosin regulatory light chain mutations disrupt myosin strain-dependent biochemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107(40):17403–17408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009619107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg MJ, et al. The molecular effects of skeletal muscle myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2009;297(2):R265–R274. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00171.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenberg MJ, Moore JR. The molecular basis of frictional loads in the in vitro motility assay with applications to the study of the loaded mechanochemistry of molecular motors. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2010;67(5):273–285. doi: 10.1002/cm.20441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg MJ, et al. Regulatory light chain mutations associated with cardiomyopathy affect myosin mechanics and kinetics. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2009;46(1):108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.09.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill AV. The heat of shortening and the dynamic constants of muscle. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1938;126(843):136–195. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1949.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang J, et al. Myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation attenuates cardiac hypertrophy. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283(28):19748–19756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802605200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacques AM, et al. Myosin binding protein C phosphorylation in normal, hypertrophic and failing human heart muscle. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2008;45(2):209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaenicke T, et al. The complete sequence of the human beta-myosin heavy chain gene and a comparative analysis of its product. Genomics. 1990;8(2):194–206. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90272-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kabaeva ZT, et al. Systematic analysis of the regulatory and essential myosin light chain genes: genetic variants and mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;10(11):741–748. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerrick WGL, et al. Malignant familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy D166V mutation in the ventricular myosin regulatory light chain causes profound effects in skinned and intact papillary muscle fibers from transgenic mice. FASEB J. 2009;23:855–865. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-118182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyata S, et al. Myosin heavy chain isoform expression in the failing and nonfailing human heart. Circ. Res. 2000;86(4):386–390. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.4.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore JR, et al. Does the myosin V neck region act as a lever? J Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2004;25(1):29–35. doi: 10.1023/b:jure.0000021394.48560.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore JR, Leinwand L, Warshaw DM. Understanding cardiomyopathy phenotypes based on the functional impact of mutations in the myosin motor. Circ. Res. 2012;111(3):375–385. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morano I. Effects of different expression and posttranslational modifications of myosin light chains on contractility of skinned human cardiac fibers. Basic Res. Cardiol. 1992;87(Suppl. 1):129–141. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-72474-9_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morano I, Osterman A, Arner A. Rate of active tension development from rigor in skinned atrial and ventricular cardiac fibres from swine following photolytic release of ATP from caged ATP. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1995;154(3):343–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1995.tb09918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muthu P, et al. The effect of myosin RLC phosphorylation in normal and cardiomyopathic mouse hearts. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2012;16(4):911–919. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01371.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muthu P, et al. In vitro rescue study of a malignant familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy phenotype by pseudo-phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chain. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014;552–553:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ngai PK, Carruthers CA, Walsh MP. Isolation of the native form of chicken gizzard myosin light-chain kinase. Biochem. J. 1984;218(3):863–870. doi: 10.1042/bj2180863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okamoto R, et al. Characterization and function of MYPT2, a target subunit of myosin phosphatase in heart. Cell. Signal. 2006;18(9):1408–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pant K, et al. Removal of the cardiac myosin regulatory light chain increases isometric force production. FASEB J. 2009 doi: 10.1096/fj.08-126672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rayment I, et al. Three-dimensional structure of myosin subfragment-1: a molecular motor. Science. 1993;261(5117):50–58. doi: 10.1126/science.8316857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richard P, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: distribution of disease genes, spectrum of mutations, and implications for a molecular diagnosis strategy. Circulation. 2003;107(17):2227–2232. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000066323.15244.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richard P, et al. Correction to: “hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: distribution of disease genes, spectrum of mutations, and implications for a molecular diagnosis strategy”. Circulation. 2004;109:3258. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000066323.15244.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richard P, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: distribution of disease genes, spectrum of mutations, and implications for a molecular diagnosis strategy. Circulation. 2003;107(17):2227–2232. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000066323.15244.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanbe A, et al. Abnormal cardiac structure and function in mice expressing nonphosphorylatable cardiac regulatory myosin light chain 2. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274(30):21085–21094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scruggs SB, et al. A novel, in-solution separation of endogenous cardiac sarcomeric proteins and identification of distinct charged variants of regulatory light chain. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2010;9(9):1804–1818. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.000075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spudich JA. Hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy: four decades of basic research on muscle lead to potential therapeutic approaches to these devastating genetic diseases. Biophys. J. 2014;106(6):1236–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spudich JA, Watt S. The regulation of rabbit skeletal muscle contraction. I. Biochemical studies of the interaction of the tropomyosin-troponin complex with actin and the proteolytic fragments of myosin. J. Biol. Chem. 1971;246(15):4866–4871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stelzer JE, Patel JR, Moss RL. Acceleration of stretch activation in murine myocardium due to phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chain. J. Gen. Physiol. 2006;128(3):261–272. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sweeney HL, Stull JT. Phosphorylation of myosin in permeabilized mammalian cardiac and skeletal muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1986;250(4 Pt 1):C657–C660. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1986.250.4.C657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szczesna-Cordary D, et al. Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-linked alterations in Ca2+ binding of human cardiac myosin regulatory light chain affect cardiac muscle contraction. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279(5):3535–3542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szczesna D, et al. Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in the regulatory light chains of myosin affect their structure, Ca2+ binding, and phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276(10):7086–7092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009823200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tardiff JC. Sarcomeric proteins and familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: linking mutations in structural proteins to complex cardiovascular phenotypes. Heart Fail. Rev. 2005;10(3):237–248. doi: 10.1007/s10741-005-5253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toepfer C, et al. Myosin regulatory light chain (RLC) phosphorylation change as a modulator of cardiac muscle contraction in disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288(19):13446–13454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.455444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y, Ajtai K, Burghardt TP. Ventricular myosin modifies in vitro step-size when phosphorylated. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014;72:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y, et al. Prolonged Ca2+ and force transients in myosin RLC transgenic mouse fibers expressing malignant and benign FHC mutations. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;361(2):286–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Warren SA, et al. Myosin light chain phosphorylation is critical for adaptation to cardiac stress. Circulation. 2012;126(22):2575–2588. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.116202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Warshaw DM, et al. The light chain binding domain of expressed smooth muscle heavy meromyosin acts as a mechanical lever. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275(47):37167–37172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]