Abstract

Introduction

Racial-ethnic minority status is a consistent risk factor for schizophrenia, with associations extending to bipolar disorder and subthreshold psychotic experiences. However, few epidemiologic studies have been conducted in the U.S., and evidence is inconsistent. Furthermore, no U.S. studies of youths have directly investigated the phenomenological overlap between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. We aimed to do so at the subthreshold level in the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort.

Methods

Participants included 6533 individuals, age 11–21 years, from a community healthcare network. Latent class analysis was used to form subtypes of sub-psychosis based on 12 attenuated positive items and 7 mania items without duration criteria. Associations between race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, “other”) and sub-psychosis subtype were estimated using latent class regression.

Results

Four classes were identified: Sub-positive Only (13.4%), Mania Only (15.5%), Both (9.1%), and Neither (62.0%). Minority participants were generally more likely than non-Hispanic whites to belong to one of the three sub-psychosis classes compared to the Neither class. Associations for Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks remained after adjustment for age, sex, and maternal education, and restriction to participants without significant physical health conditions. Racial-ethnic disparities were greater in magnitude for the two classes characterized by sub-positive symptoms, Sub-positive Only and Both, than for the Mania Only class. This pattern was statistically significant among non-Hispanic blacks.

Conclusions

We found evidence for racial-ethnic disparities in empirically-derived subtypes of subthreshold psychosis, broadly defined, among U.S. youths. Further research is needed to determine whether these disparities persist to the clinical disorder level in adulthood.

Keywords: Psychosis, Mania, Subthreshold, Race, Ethnicity, U.S. youths

1. Introduction

Racial-ethnic minority or immigrant status is a consistent risk factor for schizophrenia, particularly in Europe, although associations vary by minority group and setting (Bourque et al., 2011). European studies also indicate that this increased risk may extend to bipolar disorder and mania, suggesting that minority status may be a risk factor for psychotic disorders in general (Cantor-Graae and Pedersen, 2013; Kirkbride et al., 2012). In contrast, epidemiologic evidence for these associations in the U.S. is sparse and inconsistent (e.g., Boyd et al., 2011; Bresnahan et al., 2007; Gibbs et al., 2013; Kendler et al., 1996).

However, both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are thought to reflect underlying continua (Angst, 2007a; van Os et al., 2009), and studies from both the U.S. and abroad indicate that there may be racial-ethnic disparities in psychosis at the subthreshold level both among adults (Cohen and Marino, 2013; Morgan et al., 2009; Scott et al., 2006) and among children and adolescents (Adriaanse et al., 2015; Calkins et al., 2014; Laurens et al., 2008; Vanheusden et al., 2008; Wigman et al., 2011). In the only U.S.-based study of young people, Calkins et al. (2014) found that psychosis spectrum was more common among non-white than white youths. Similarity in genetic and non-genetic risk factors at threshold and subthreshold levels suggests that there may be phenomenological or etiological continuity between formal psychotic disorder and psychotic or psychosis-like experiences (Linscott and van Os, 2013).

At the same time, there is accumulating evidence for overlap between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in both genetic and non-genetic risk factors, prompting suggestions that the two disorders have at least partly shared etiology (Craddock et al., 2009; Demjaha et al., 2012). There is also overlap between the two disorders phenomenologically (Angst, 2007b; Kendler et al., 1998). By and large, however, epidemiologic studies treat the two disorders separately, and the contribution of risk factors to overlapping phenomena (e.g., Laursen et al., 2007) is seldom explicitly investigated.

The objective of this study was to assess racial-ethnic disparities in broadly-defined subclinical psychosis among a U.S. general pediatrics sample. We extend previous findings (Calkins et al., 2014) by empirically deriving subgroups that allow for the naturally-occurring overlap of attenuated positive symptoms and broad mania. To our knowledge, this is the first U.S. study of the association between minority status and subclinical psychosis to investigate this overlap.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

Participants were from the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort, a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grand Opportunity study of children and youths recruited through the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) healthcare network between 2006 and 2012 (Calkins et al., 2015). This network includes over 30 community clinical sites in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware. Participants were not recruited from psychiatric clinics. Participants initially presented for a range of pediatric services including well child visits, minor medical problems, chronic conditions, and severe illness. From a pool of 50 293 children who participated in an initial genotyping study and provided access to electronic medical records (EMRs), participants were randomly selected stratified on age, sex, and race-ethnicity. Based on EMR screen, youth were included if they were 8–21 years old, proficient in English, had provided written informed consent/assent to be contacted for future studies, resided in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, or Delaware, and lacked significant developmental delays or other conditions that would preclude the ability to complete study procedures. Among 19,161 eligible children, 13,598 were invited, 9498 were enrolled, and 9412 participated. Details of the study sample and enrollment procedure have been published (Calkins et al., 2015).

Written informed consent was obtained from participants aged 18 or older and written assent and parental permission were obtained for participants under age 18. Procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Pennsylvania and CHOP.

2.2. Measures

A computerized structured interview (GOASSESS), based on an abbreviated version of the NIMH Genetic Epidemiology Research Branch Kiddie-SADS (Kessler et al., 2009), was administered by bachelor and master level assessors who underwent rigorous training, certification, and monitoring (Calkins et al., 2015). Interviews were conducted with participants only (age 18–21), participants and a parent or guardian (age 11–17), or parents/guardians only (age 8–10). The GOASSESS included information on demographics, medical history, and mental health (Merikangas et al., 2015).

2.2.1. Sub-positive and mania symptoms

Subthreshold positive symptoms were measured using the 12-item PRIME Screen — Revised (Kobayashi et al., 2008). These included odd or unusual thoughts, auditory perceptions, reality confusion, audible thoughts, grandiosity, mind tricks, superstitions, persecutory or suspicious thoughts, predicting the future, mind reading, thought control, and concern about “going crazy”. Adolescents were read each item aloud and asked to rate their agreement on a 7-point scale (“definitely disagree” to “definitely agree”.) Symptoms were coded as present if the adolescent's response indicated slight (4 on the scale) or greater agreement. This cutoff is one point lower than that used to score the PRIME Screen to identify youth at high risk for psychosis in clinical settings (Calkins et al., 2014) and has been applied previously in non-clinical samples (Kobayashi et al., 2008).

Mania symptoms, including increased motor activity, increased energy, decreased need for sleep, flight of speech or ideas, elevated mood, grandiosity, and irritable mood, were drawn from the Mania section of the GOASSESS. Endorsed symptoms were coded as present if the adolescent reported that either other people noticed or worried about him/her, or the experience differed from how s/he usually is. No duration, impairment, or distress criteria were imposed.

2.2.2. Physical health

The medical history section of the GOASSESS assessed 42 categories of physical conditions that were used to complement information from the EMRs. Each condition was rated from 0 to 4 (0 = No medical problems; 1 = Minor, no central nervous system impact; 2 = Moderate; 3 = Significant; 4 = Major). This information was used to indicate a subgroup of participants without any significant to major physical health conditions (ratings of 0 or 1 only).

2.2.3. Demographics

Demographics included age in months, sex, and self-identified race-ethnicity [non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and “other” (native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaskan native, more than one race)]. Maternal education in years (<12, 12, 13–15, 16–20) was included as an indicator of family socioeconomic status.

2.3. Analytic sample

Analysis focused on the 7050 participants aged 11–21 for whom personal interviews, rather than parent/guardian interviews alone, were available. Because this sample included siblings, we randomly selected one child from each of the 6612 families using the sample command in Stata 13 (StataCorp, 2013). Of these, 79 did not respond to any psychosis or mania items and were therefore ineligible for further analysis. The final analytic sample size was 6533.

2.4. Analysis

Means and frequencies were used to describe the distribution of sample characteristics overall and by racial-ethnic group. Differences were tested via chi-squared tests and equality-of-median tests.

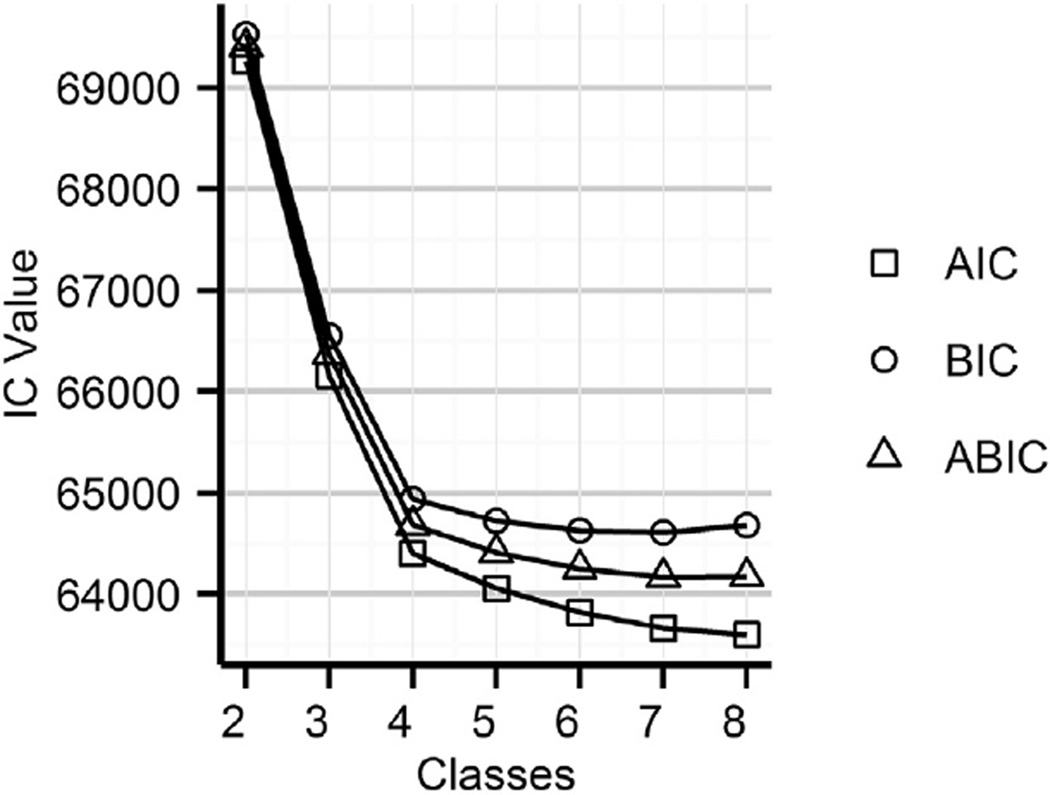

Latent Class Analysis (LCA), performed in MPlus version 6.1, was used to classify participants into mutually exclusive and exhaustive groups based on their responses to the 19 sub-positive and mania symptoms (Muthén and Muthén, 2010). Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation was used, which assumes that missing data (less than 0.34% for any given indicator) are ignorable given variables included in the analysis (Collins and Lanza, 2010). We considered models with 2 through 8 classes, with the goal of identifying the most parsimonious and substantively interpretable model that demonstrated adequate relative fit. Model details are provided in eTable 1 (Supplement). In settings with large numbers of indicators and large sample sizes, additional latent classes tend to produce statistically significant but trivial increases in likelihood (Nylund et al., 2007). We therefore focused on BIC (Schwarz, 1978) and adjusted BIC (Sclove, 1987) to identify the point at which additional classes no longer produced appreciable increases in model fit (Collins and Lanza, 2010). (Nylund et al., 2007). Fig. 1 displays all three information criteria for models with 2– 8 classes. A point of diminishing returns was observed whereby models with more than 4 classes resulted in smaller and smaller increases in information (Collins and Lanza, 2010). The four-class model also was most directly pertinent to the research question at hand and was therefore selected for remaining analyses. The entropy statistic for the four-class model was .887, indicating good classification quality.

Fig. 1.

Information criteria for 2- through 8-class latent class models.

We performed Latent Class Regression (LCR) to estimate unadjusted associations of age, sex, maternal education (missing for 1.6%), race-ethnicity, and physical health (missing for 0.61%) with latent class membership, as well as to estimate adjusted associations between race-ethnicity and latent class membership. Resulting odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) represent the probability of being in a given latent class compared to a reference class. LCR was performed using the 4-class model selected during LCA, and the threshold estimates from the LCA were used as starting values for the corresponding indicators in the LCR. Measurement invariance was assessed using multiple-group analysis (see Supplement).

3. Results

Table 1 shows characteristics of the full sample and by racial-ethnic group. The sample was 54% female and mean age 15.8. About 43% of participants had mothers with 16 or more years of education. Overall, 40% endorsed any sub-positive item, 32% endorsed any mania item, and 31% had a significant to major physical health condition. All characteristics except for age differed by racial-ethnic group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics overall and by racial-ethnic group.

| Overall (n = 6533) |

Non-Hispanic white (n = 3626) |

Hispanic (n = 407) |

Non-Hispanic black (n = 2052) |

Another race–ethnicity (n = 448) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (n, %) | |||||

| Male | 2978 (45.6) | 1754 (47.9) | 172 (41.7) | 900 (43.3) | 201 (44.2) |

| Female | 3555 (54.4) | 1911 (52.1) | 241 (58.4) | 1179 (56.7) | 254 (55.8) |

| Age (mean, sd) | 15.81 (2.7) | 15.78 (2.71) | 15.91 (2.8) | 15.91 (2.8) | 15.56 (2.7) |

| Maternal education (n, %) | |||||

| <12 years | 284 (4.4) | 57 (1.6) | 26 (6.4) | 189 (9.4) | 18 (4.0) |

| 12 years | 1844 (28.7) | 788 (21.7) | 132 (32.5) | 841 (41.7) | 109 (24.3) |

| 13–15 years | 1570 (24.4) | 796 (21.9) | 115 (28.3) | 554 (27.4) | 117 (26.0) |

| 16+ years | 2731 (42.5) | 1987 (54.8) | 133 (32.8) | 435 (21.6) | 205 (45.7) |

| Any sub-positive symptom (n, %) | |||||

| Yes | 2624 (40.2) | 1188 (32.8) | 186 (45.7) | 1065 (52.0) | 185 (41.3) |

| No | 3905 (59.8) | 2438 (67.2) | 221 (54.3) | 983 (48.0) | 263 (58.7) |

| Any mania symptom (n, %) | |||||

| Yes | 2064 (31.6) | 1049 (28.9) | 145 (35.6) | 724 (35.3) | 146 (32.6) |

| No | 4469 (68.4) | 2577 (71.1) | 262 (64.4) | 1328 (64.7) | 302 (67.4) |

| Health conditions (n, %) | |||||

| Yes | 1999 (30.8) | 1235 (33.9) | 144 (34.9) | 515 (25.0) | 151 (33.3) |

| No | 4494 (69.2) | 2410 (66.1) | 269 (65.1) | 1543 (75.0) | 303 (66.7) |

Note: “Other” group includes Asian (n = 53), American Indian or Alaskan Native (n = 12), Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (n = 4), and more than one race (n = 379). Race-ethnicity differed significantly by sex (χ2 = 14.41, df = 3, p=.002), maternal education (χ2 = 721.21, df = 9, p < .001), sub-positive (χ2 = 207.44, df = 3, p < .001),mania(χ2 = 28.09, df = 3, p < .001), and the presence of health conditions (χ2 = 53.75, df = 3, p < .001).

Fig. 2 displays the 4-class latent class solution. The most prevalent class, comprising an estimated 62% of the sample, was characterized by low estimated probabilities of endorsement for all items and is referred to as the “Neither” class. The three other classes represent subtypes of subthreshold psychosis. An estimated 15.5% of participants had relatively high probabilities of endorsing mania symptoms but low probabilities of endorsing sub-positive symptoms (“Mania Only” class). An estimated 13.4% of participants had low estimated probabilities of endorsing mania symptoms but relatively high probabilities of endorsing sub-positive symptoms (“Sub-positive Only” class). An estimated 9.1% of participants had relatively high probabilities of endorsing both types of symptoms (“Both” class).

Fig. 2.

4-class model of latent sub-psychosis subtypes. 7 mania symptoms and 12 attenuated positive symptoms are shown on the horizontal axis. The vertical axis shows the estimated probability of endorsing each symptom for each of the 4 classes. Classes were labeled Mania Only (circles), Sub-positive Only (plus signs), Both (squares), and Neither (triangles).

Table 2 shows unadjusted associations between demographics and latent class membership. Females were less likely than males to be in the Sub-positive Only class compared to the Neither class. Older children were slightly less likely to be in the Sub-positive Only and Both classes and more likely to be in the Mania Only class. Compared to non-Hispanic whites, all 3 minority groups were more likely to be in one of the psychosis classes compared to the Neither class, with the exception that those in the “other” racial-ethnic group were not significantly more likely to be in the Mania Only class. Lower levels of maternal education were generally associated with being in one of the psychosis classes compared to the Neither class. Those with physical health conditions were also more likely to belong to one of the psychosis classes compared to the Neither class.

Table 2.

Unadjusted associations between sample characteristics and latent class membership.

| Sub-positive Only | Mania Only | Both | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | .78 | (.66, .92) | .94 | (.80, 1.09) | .90 | (.75, 1.09) |

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Age in years | .87 | (.84, .90) | 1.05 | (1.02, 1.08) | .96 | (.93, .99) |

| Race-ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 2.27 | (1.63, 3.15) | 1.62 | (1.20, 2.18) | 1.80 | (1.22, 2.65) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 2.72 | (2.25, 3.28) | 1.43 | (1.20, 1.17) | 2.51 | (2.04, 3.09) |

| Other | 1.69 | (1.21, 2.35) | 1.15 | (.85, 1.56) | 1.51 | (1.03, 2.21) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Maternal education | ||||||

| <12 years | 2.89 | (2.01, 4.17) | 1.68 | (1.17, 2.42) | 2.73 | (1.77, 4.21) |

| 12 years | 1.65 | (1.34, 2.03) | 1.29 | (1.07, 1.55) | 2.00 | (1.58, 2.53) |

| 13–15 years | 1.60 | (1.29, 1.98) | 1.15 | (.95, 1.40) | 1.86 | (1.45, 2.38) |

| 16 + years | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Physical health conditions | ||||||

| Significant to moderate | 1.40 | (1.18, 1.67) | 1.19 | (1.01, 1.40) | 1.49 | (1.22, 1.81) |

| None to mild | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

Note: OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. “Neither” class is reference.

Table 3 shows adjusted associations between race-ethnicity and class membership. Adjustment for age and sex alone (Table 3, top) resulted in little change from the unadjusted estimates in Table 2. Excluding those with significant to major physical health conditions (Table 3, middle) produced some change in estimates and can be interpreted as quantifying the racial-ethnic disparity before accounting for potential mediators. Compared to non-Hispanic whites, Hispanic and non-Hispanic black youths had higher odds of being in all three psychosis classes compared to the Neither class. Within each class, OR magnitudes were greater for non-Hispanic blacks than for Hispanics, although this difference was not statistically significant. ORs for those in the “other” racial-ethnic group were lower than those of the other two minority groups, and indicated significantly increased odds only for being in the Sub-positive Only class. Across outcomes, there was a pattern whereby ORs for being in the Sub-positive Only and Both classes were greater in magnitude than those for being in the Mania Only class. This pattern was statistically significant only among non-Hispanic blacks. Additional adjustment for maternal education produced slight reductions in estimates (Table 3, bottom). The general pattern of associations was unchanged, except that the OR for being in the Sub-positive Only class for the “other” racial-ethnic group was no longer statistically significant.

Table 3.

Adjusted associations between race-ethnicity and latent class membership.

| Sub-positive Only | Mania Only | Both | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Adjusted for age and sex (n = 6533): | ||||||

| Hispanic | 2.37 | (1.70, 3.30) | 1.61 | (1.21, 2.19) | 1.85 | (1.25, 2.73) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 2.79a | (2.31, 3.37) | 1.44b,c | (1.20, 1.71) | 2.57a | (2.09, 3.17) |

| Other | 1.63 | (1.16, 2.28) | 1.18 | (.87, 1.60) | 1.51 | (1.03, 2.21) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Adjusted for age and sex, and excluding those with physical health conditions (n = 4494): | ||||||

| Hispanic | 2.15 | (1.38, 3.34) | 1.61 | (1.11, 2.31) | 2.47 | (1.50, 4.06) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 3.09a | (2.45, 3.91) | 1.56b,c | (1.26, 1.92) | 3.18a | (2.40, 4.21) |

| Other | 1.64 | (1.05, 2.58) | 1.20 | (.84, 1.72) | 1.53 | (.89, 2.63) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Adjusted for age, sex, and maternal education, and excluding those with physical health conditions (n = 4433): | ||||||

| Hispanic | 1.93 | (1.23, 3.03) | 1.57 | (1.09, 2.27) | 2.13 | (1.29, 3.53) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 2.59a | (2.01, 3.33) | 1.48b,c | (1.18, 1.84) | 2.63a | (1.94, 3.58) |

| Other | 1.54 | (.97, 2.44) | 1.12 | (.78, 1.62) | 1.50 | (.87, 2.58) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

Note: OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. “Neither” class is reference. Age adjustment includes a quadratic term, as it improved model fit (χ2 = 17.404, df = 1, p < .001).

Different from OR for Mania Only (p < .05).

Different from OR for Both (p < .05).

Different from OR for Sub-positive only (p < .05).

4. Discussion

We found racial-ethnic disparities in empirically-derived subtypes of subthreshold psychosis, broadly defined, in a U.S. sample of youths. Hispanics, non-Hispanic blacks, and youths of “other” race-ethnicity were more likely than non-Hispanic white youths to fall into latent classes that reflect attenuated positive symptoms only, mania symptoms only, and both positive and mania symptoms. Associations for Hispanic and non-Hispanic black youths remained after adjustment for age, sex and maternal education, and restriction to those without physical health conditions. Estimates indicated that odds were greater for the Sub-positive Only class and the Both class than for the Mania Only class, a pattern that was statistically significant among non-Hispanic blacks. This study adds to evidence for racial-ethnic disparities in mental health (Miranda et al., 2008) and extends previous work in this sample (Calkins et al., 2014) by explicitly modeling phenomenological overlap between subthreshold positive symptoms and mania. The moderate estimated prevalence of the Both class indicated an appreciable degree of naturally-occurring overlap in subthreshold symptomatology.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies reporting racial-ethnic disparities in subthreshold psychosis among children and adolescents. Laurens et al. (2008) found that African-Caribbean children in the U.K. were more likely than White British children to report any psychosis-like experience. Adriaanse et al. (2015) reported that Moroccan, Turkish, and other minority youths in The Netherlands were more likely to have higher impact psychotic experiences compared to Dutch youths. We were unable to locate studies in youth that have investigated differences by symptom type to assess overlap with mania. However, racial-ethnic differences in the prevalence of mania symptoms were reported in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study (Weissman et al., 1991), with 6 of 8 symptoms being more common among blacks and less common among Hispanics, although pairwise comparisons were not reported. In the National Comorbidity Survey Adolescent Supplement rates of mania without major depression were significantly higher among Hispanics, and non-significantly elevated among non-Hispanic blacks, compared to non-Hispanic whites (Merikangas et al., 2012). Our findings, along with others discussed here, are also broadly consistent with studies demonstrating greater risk for psychotic disorders among racial-ethnic minorities (e.g., Bresnahan et al., 2007; Kirkbride et al., 2012). Such consistency supports the idea that subthreshold psychosis may be etiologically continuous with clinical disorder (Linscott and van Os, 2013).

Our results imply both generality and specificity of association between minority status and subtypes of sub-psychosis. Although odds of all three subtypes were increased among minority participants, the magnitude of such increases differed. These differences were statistically significant among non-Hispanic blacks but were also apparent, to a lesser extent, among Hispanics. This finding of partial risk factor overlap is consistent with evidence for partial genetic overlap at the disorder level (Craddock et al., 2009), and with developmental models that include a degree of shared disorder etiology (Demjaha et al., 2012). Such overlap is not surprising considering that racial-ethnic categories encapsulate a collection of potentially causal exposures that may differ in degree of specificity. Explanations for racial-ethnic differences in psychosis risk have largely focused on psychosocial mechanisms such as exposure to social defeat, discrimination, and other forms of adversity (Morgan et al., 2010; Oh et al., 2014; Selten et al., 2013). Biological risk factors such as vitamin D deficiency and exposure to cannabis have also received attention (McGrath et al., 2010; Morgan et al., 2010). The constellation or dose of exposures may differ on average between minority groups, consistent with heterogeneity in psychosis risk among racial-ethnic subgroups at the disorder level (Bourque et al., 2011). Further work is needed to identify which of the potential exposures represented by race-ethnicity are operating to increase risk of subthreshold psychoses among young people.

Alternatively, subthreshold psychotic symptoms may simply be markers of psychiatric distress, comorbidity, or severity (DeVylder et al., 2014; Downs et al., 2013; McGorry et al., 2006). The presence of subthreshold psychotic symptoms may therefore reflect the general mental health disadvantage faced by youth who experience them. Such an interpretation is consistent with previous studies reporting greater psychological distress among U.S. minorities (Brown et al., 2007; Williams and Earl, 2007) and with evidence that non-white race-ethnicity is similarly associated with psychotic experiences and depression among adolescents in the UK (Kounali et al., 2014). However, longitudinal studies have found that attenuated psychosis or psychosis-like symptoms predict subsequent psychotic disorder in both adolescents (Zammit et al., 2013) and adults (Werbeloff et al., 2012). An important area of future research is to determine whether the disparities observed here persist to the level of clinical significance, and if so, which sets of single or multiple overlapping syndromes are impacted (van Os, 2013).

This study has a number of limitations. The use of a secondary treatment sample raises the possibility of selection bias and may limit the generalizability of our findings. Youth were required to be proficient in English, precluding generalizability to non-English-speaking minorities. Racial-ethnic categorizations were broad, and within-group heterogeneity is likely present. Replication of these findings among larger subgroups is necessary to confirm apparent subgroup differences as well as to reduce within-group heterogeneity. Cultural differences between groups may also have influenced our results despite assessment for measurement invariance. For example, cultural variation in the normative expression of spirituality or ways of coping with death or trauma could lead to differential rates of endorsement of experiences such as auditory perceptions (Earl et al., 2015). We lacked information on nativity that would allow for differentiation between racial-ethnic minority status and immigration status (Breslau and Chang, 2006). For example, some studies have suggested that first generation Latino immigrants to the U.S. may be at lower risk for psychotic experiences compared to later generations (Oh et al., 2015; Vega et al., 2006). Finally, although we had access to information on maternal education level, we were unable to assess other candidate explanations for the observed disparities.

Study strengths include access to a large, systematic sample of U.S. youths who were not recruited from psychiatric settings. We had information on both subthreshold positive psychotic and manic symptoms, allowing us to explicitly model their overlap. Symptoms were reported by respondents during a standardized and structured interview, reducing the possibility that results were driven by clinician bias. Participants were young and had not yet passed through the period of greatest risk for onset of psychotic disorder, meaning that our measures are developmentally proximate to the mechanisms underlying psychotic phenomena. Finally, the availability of physical health information allowed restriction to those without physical health conditions, which reduces the possible influence of selection bias due to physical health treatment-seeking.

To our knowledge, it is the first study of racial-ethnic disparities in psychosis among U.S. youth that includes overlap with subthreshold mania. We found evidence for both generality and specificity of the association between race-ethnicity and subtypes of subthreshold psychosis. Studies of epidemiologic differences between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder may benefit from directly modeling their overlap. An important area for future research is to determine whether these disparities are also present at clinically significant levels in adulthood and how they may be prevented.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Role of funding source

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health (1ZIAMH002931-01), grants RC2MH089983, RC2MH089924, K08MH079364, P50-MH096891 from the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Dowshen Program for Neuroscience.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or US government.

We thank the teams at Penn and CHOP who have contributed to data collection and processing.

Footnotes

Author contributions

D. Paksarian designed the study, conducted the analyses, and drafted the manuscript. K.R. Merikangas assisted with data interpretation and revised the manuscript. M.E. Calkins and R.E. Gur designed and conducted the parent study and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Raquel Gur participated in an advisory board for Otsuka unrelated to the study. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Results from this study were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychopathological Association on March 5th, 2015, and the International Congress on Schizophrenia Research on March 29th, 2015 (abstract: Schizophrenia Bulletin (2015) 41(Supp. 1): S149).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2015.12.004.

References

- Adriaanse M, van Domburgh L, Hoek HW, Susser E, Doreleijers TAH, Veling W. Prevalence, impact and cultural context of psychotic experiences among ethnic minority youth. Psychol. Med. 2015;45(3):637–646. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst J. The bipolar spectrum. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2007a;190:189–191. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.030957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst J. Psychiatric diagnoses: the weak component of modern research. World Psychiatry. 2007b;6(2):94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourque F, Van der Ven E, Malla A. A meta-analysis of the risk for psychotic disorders among first-and second-generation immigrants. Psychol. Med. 2011;41(05):897–910. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd RC, Joe S, Michalopoulos L, Davis E, Jackson JS. Prevalence of mood disorders and service use among US mothers by race and ethnicity: results from the national survey of American life. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2011;72(11):1538–1545. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Chang DF. Psychiatric disorders among foreign-born and US-born Asian-Americans in a US national survey. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2006;41(12):943–950. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0119-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnahan M, Begg MD, Brown A, Schaefer C, Sohler N, Insel B, Vella L, Susser E. Race and risk of schizophrenia in a US birth cohort: another example of health disparity? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2007;36(4):751–758. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JS, Meadows SO, Elder GH., Jr Race-ethnic inequality and psychological distress: depressive symptoms from adolescence to young adulthood. Dev. Psychol. 2007;43(6):1295. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins ME, Merikangas KR, Moore TM, Burstein M, Behr MA, Satterthwaite TD, Ruparel K, Wolf DH, Roalf DR, Mentch FD. The philadelphia neurodevelopmental cohort: constructing a deep phenotyping collaborative. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins ME, Moore TM, Merikangas KR, Burstein M, Satterthwaite TD, Bilker WB, Ruparel K, Chiavacci R, Wolf DH, Mentch F. The psychosis spectrum in a young US community sample: findings from the Philadelphia neurodevelopmental cohort. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):296–305. doi: 10.1002/wps.20152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor-Graae E, Pedersen CB. Full spectrum of psychiatric disorders related to foreign migration: a Danish population-based cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(4):427–435. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CI, Marino L. Racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence of psychotic symptoms in the general population. Psychiatr. Serv. 2013;64(11):1103–1109. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Lanza ST. Parameter estimation and model selection, latent class and latent transition analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2010. pp. 77–109. [Google Scholar]

- Craddock N, O'Donovan MC, Owen MJ. Psychosis genetics: modeling the relationship between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and mixed (or “schizoaffective”) psychoses. Schizophr. Bull. 2009;35(3):482–490. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demjaha A, MacCabe JH, Murray RM. How genes and environmental factors determine the different neurodevelopmental trajectories of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr. Bull. 2012;38(2):209–214. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVylder JE, Burnette D, Yang LH. Co-occurrence of psychotic experiences and common mental health conditions across four racially and ethnically diverse population samples. Psychol. Med. 2014;44(16):3503–3513. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs JM, Cullen AE, Barragan M, Laurens KR. Persisting psychotic-like experiences are associated with both externalising and internalising psychopathology in a longitudinal general population child cohort. Schizophr. Res. 2013;144(1–3):99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earl TR, Fortuna LR, Gao S, Williams DR, Neighbors H, Takeuchi D, Alegria M. An exploration of how psychotic-like symptoms are experienced, endorsed, and understood from the national Latino and Asian American study and national survey of American life. Ethn. Health. 2015;20(3):273–292. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2014.921888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs TA, Okuda M, Oquendo MA, Lawson WB, Wang S, Thomas YF, Blanco C. Mental health of African Americans and Caribbean blacks in the United States: results from the national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions. Am. J. Public Health. 2013;103(2):330–338. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gallagher TJ, Abelson JM, Kessler RC. Lifetime prevalence, demographic risk factors, and diagnostic validity of nonaffective psychosis as assessed in a US community sample: the national comorbidity survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1996;53(11):1022–1031. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110060007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Walsh D. The structure of psychosis: latent class analysis of probands from the Roscommon family study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1998;55(6):492–499. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.6.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Green J, Gruber MJ, Guyer M, He Y, Jin R, Kaufman J, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Merikangas KR. National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): III. Concordance of DSM-IV/CIDI diagnoses with clinical reassessments. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2009;48(4):386–399. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819a1cbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkbride JB, Errazuriz A, Croudace TJ, Morgan C, Jackson D, Boydell J, Murray RM, Jones PB. Incidence of schizophrenia and other psychoses in England, 1950–2009: a systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e31660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H, Nemoto T, Koshikawa H, Osono Y, Yamazawa R, Murakami M, Kashima H, Mizuno M. A self-reported instrument for prodromal symptoms of psychosis: testing the clinical validity of the PRIME screen—revised (PS-R) in a Japanese population. Schizophr. Res. 2008;106(2):356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kounali D, Zammit S, Wiles N, Sullivan S, Cannon M, Stochl J, Jones P, Mahedy L, Gage S, Heron J. Common versus psychopathology-specific risk factors for psychotic experiences and depression during adolescence. Psychol. Med. 2014;44(12):2557–2566. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurens K, West S, Murray R, Hodgins S. Psychotic-like experiences and other antecedents of schizophrenia in children aged 9–12 years: a comparison of ethnic and migrant groups in the United Kingdom. Psychol. Med. 2008;38(08):1103–1111. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Nordentoft M, Bo MP. A comparison of selected risk factors for unipolar depressive disorder, bipolar affective disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia froma Danish population-based cohort. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2007;68(11):1673–1681. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linscott R, van Os J. An updated and conservative systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence on psychotic experiences in children and adults: on the pathway from proneness to persistence to dimensional expression across mental disorders. Psychol. Med. 2013;43(06):1133–1149. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Hickie IB, Yung AR, Pantelis C, Jackson HJ. Clinical staging of psychiatric disorders: a heuristic framework for choosing earlier, safer and more effective interventions. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2006;40(8):616–622. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JJ, Eyles DW, Pedersen CB, Anderson C, Ko P, Burne TH, Norgaard-Pedersen B, Hougaard DM, Mortensen PB. Neonatal vitamin D status and risk of schizophrenia: a population-based case–control study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2010;67(9):889–894. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Calkins ME, Burstein M, He J-P, Chiavacci R, Lateef T, Ruparel K, Gur RC, Lehner T, Hakonarson H. Comorbidity of physical and mental disorders in the neurodevelopmental genomics cohort study. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):e927–e938. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Cui L, Kattan G, Carlson GA, Youngstrom EA, Angst J. Mania with and without depression in a community sample of US adolescents. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2012;69(9):943–951. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, McGuire TG, Williams DR, Wang P. Mental health in the context of health disparities. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2008;165(9):1102–1108. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan C, Charalambides M, Hutchinson G, Murray RM. Migration, ethnicity, and psychosis: toward a sociodevelopmental model. Schizophr. Bull. 2010;36(4):655–664. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan C, Fisher H, Hutchinson G, Kirkbride J, Craig TK, Morgan K, Dazzan P, Boydell J, Doody GA, Jones PB, Murray RM, Leff J, Fearon P. Ethnicity, social disadvantage and psychotic-like experiences in a healthy population based sample. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2009;119(3):226–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Muthén L. Mplus Version 6.1. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007;14(4):535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Abe J, Negi N, DeVylder J. Immigration and psychotic experiences in the United States: another example of the epidemiological paradox? Psychiatry Res. 2015;229(3):784–790. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Yang LH, Anglin DM, DeVylder JE. Perceived discrimination and psychotic experiences across multiple ethnic groups in the United States. Schizophr. Res. 2014;157(1–3):259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann. Stat. 1978;6(2):461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Sclove SL. Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika. 1987;52(3):333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Scott J, Chant D, Andrews G, McGrath J. Psychotic-like experiences in the general community: the correlates of CIDI psychosis screen items in an Australian sample. Psychol. Med. 2006;36(02):231–238. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selten J-P, van der Ven E, Rutten BP, Cantor-Graae E. The social defeat hypothesis of schizophrenia: an update. Schizophr. Bull. 2013;39(6):1180–1186. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- van Os J. The dynamics of subthreshold psychopathology: implications for diagnosis and treatment. The American journal of psychiatry. 2013;170(7):695–698. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13040474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Os J, Linscott RJ, Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul P, Krabbendam L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: evidence for a psychosis proneness–persistence–impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychol. Med. 2009;39(02):179–195. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanheusden K, Mulder C, van der Ende J, Selten J-P, Van Lenthe F, Verhulst F, Mackenbach J. Associations between ethnicity and self-reported hallucinations in a population sample of young adults in The Netherlands. Psychol. Med. 2008;38(08):1095–1102. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Sribney WM, Miskimen TM, Escobar JI, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Putative psychotic symptoms in the Mexican American population: prevalence and co-occurrence with psychiatric disorders. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2006;194(7):471–477. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000228500.01915.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Bruce ML, Leaf PJ, Florio LP, Holzer CI. Affective disorders. In: Robins LN, Regier DA, editors. Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. New York: The Free Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Werbeloff N, Drukker M, Dohrenwend BP, Levav I, Yoffe R, van Os J, Davidson M, Weiser M. Self-reported attenuated psychotic symptoms as forerunners of severe mental disorders later in life. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2012;69(5):467–475. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigman JTW, van Winkel R, Raaijmakers QAW, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, Reijneveld SA, van Os J, Vollebergh WAM. Evidence for a persistent, environment-dependent and deteriorating subtype of subclinical psychotic experiences: a 6-year longitudinal general population study. Psychol. Med. 2011;41(11):2317–2329. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Earl TR. Race and mental health: more questions than answers. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2007;36(4):758–760. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zammit S, Kounali D, Cannon M, David AS, Gunnell D, Heron J, Jones PB, Lewis S, Sullivan S, Wolke D, Lewis G. Psychotic experiences and psychotic disorders at age 18 in relation to psychotic experiences at age 12 in a longitudinal population-based cohort study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2013;170(7):742–750. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12060768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.