Abstract

The high-neurovirulence Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) strain GDVII uses heparan sulfate (HS) as a coreceptor to enter target cells. We report here that GDVII virus adapted to growth in HS-deficient cells exhibited two amino acid substitutions (R3126L and N1051S) in the capsid and no longer used HS as a coreceptor. Infectious-virus yields in CHO cells were 25-fold higher for the adapted virus than for the parental GDVII virus, and the neurovirulence of the adapted virus in intracerebrally inoculated mice was substantially attenuated. The adapted virus showed altered cell tropism in the central nervous systems of mice, shifting from cerebral and brainstem neurons to spinal cord anterior horn cells; thus, severe poliomyelitis, but not acute encephalitis, was observed in infected mice. These data indicate that the use of HS as a coreceptor by GDVII virus facilitates cell entry and plays an important role in cell tropism and neurovirulence in vivo.

Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis viruses (TMEV) are divided into two groups based on neurovirulence following intracerebral (i.c.) inoculation of mice. High-neurovirulence strains, such as GDVII, produce fatal encephalitis in mice, while low-neurovirulence strains, such as BeAn and DA, induce early poliomyelitis followed by persistent infection in the central nervous system (CNS) and demyelinating disease in mice (26, 28). Members of both neurovirulence groups are 90% identical in nucleotide sequences, 95% identical in amino acid contents, and differ only slightly in their overall three-dimensional structures (31). Despite their close genetic and structural relatedness, these viruses differ significantly in their mode of binding to mammalian cells (35, 39) and in their association with intracellular membranes during replication (8).

TMEV use at least two molecules for attachment and cell entry (19). Recent studies have shown that low-neurovirulence strains bind α2,3 sialic acid moieties on N-linked oligosaccharides (7, 39, 42), while high-neurovirulence strains attach to the proteoglycan heparan sulfate (HS) (35). Brain-derived stocks of GDVII virus bind HS (35), indicating that this interaction is not an artifact of cell culture adaptation of the virus. Since TMEV are picornaviruses, nonenveloped viruses which are unable to fuse with the lipid bilayer of cells, internalization is believed to require a specific protein entry receptor. Viruses of both TMEV neurovirulence groups have been shown to bind an as yet unidentified sialylated 34-kDa protein in a ligand (virus) protein overlay assay (21, 27).

To gain further insight into cell entry by TMEV, we focused on the interaction between high-neurovirulence GDVII and HS by using GDVII virus adapted to proteoglycan-deficient cells. The adapted virus, designated GD-A745, acquired two mutations, both on surface loops in the capsid. GD-A745 no longer used HS for binding and entry, and its neurovirulence in mice was attenuated compared to parental GDVII. Neuronal tropism in GD-A745-infected adult mice changed from cerebral and brainstem neurons to spinal cord anterior horn cells, resulting in flaccid paralysis typical of poliomyelitis but no signs of encephalitis. Thus, the clinicopathologic phenotype of GD-A745 infection more closely resembles that of the low-neurovirulence TMEV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses.

The origin and preparation of the TMEV BeAn and GDVII stocks as clarified lysates in BHK-21 cells were described previously (37).

Cells.

BHK-21 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 mg of streptomycin/ml, 100 U of penicillin/ml, 7.5% fetal bovine serum, and 6.5 mg of tryptose phosphate broth (Gibco-BRL)/ml at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. CHO and sialic-acid-deficient Lec-2 cells were maintained in minimum essential medium supplemented with 100 mg of streptomycin/ml, 100 U of penicillin/ml, and 10% Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium. Proteoglycan-deficient pgsA-745 and pgsD-677 CHO cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium-F-12 medium. Mouse neuroblastoma cells (Neuro-2A) were maintained in Eagle's minimum essential medium supplemented as described above. Murine macrophage M1-D cells were derived from M1 myelomonocytic precursor cells and maintained in culture as described previously (17).

Reagents.

HS from bovine kidney and anti-HS antibody F58-10E4 conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) were purchased from Seikagaku America Inc.; goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G-FITC, the MTT reagent 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, and neuraminidase (Clostridium perfringens; type V) were from Sigma; and TriZol reagent was from Life Technologies (Rockville, Md.). Rabbit polyclonal antibody to BeAn virus was prepared as described previously (29).

Virus titrations.

The virus titers of clarified cell lysates and 10% clarified homogenates of mouse brains and spinal cords were determined by standard plaque assay in duplicate on BHK-21 cell monolayers in six-well plates as described previously (37).

Dideoxynucleotide sequencing.

Total RNA isolated from GD-A745 virus-infected cells using TriZol reagent was reverse transcribed (1.2 μg of RNA in a 25-μl reaction mixture) using Thermoscript reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies) in the presence of specific primers (1.8 μM). Two microliters of each cDNA reaction mixture was PCR amplified in a 50-μl reaction mixture using negative-strand and positive-strand primers in the GDVII genome to produce PCR products between 1.5 and 2.0 kb in length. Gel-purified PCR products were sequenced using the ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems) and analyzed using MacVector software.

Cell death assay.

Virus was adsorbed to cell monolayers in quadruplicate with uninfected cells as controls in 96-multiwell plates, and cell viability was determined by MTT assay as described previously (5). Cell death was calculated as a percentage of uninfected-cell controls. For inhibition, virus was preincubated with soluble HS at 37°C for 1 h before adsorption to cells for 45 min at 24°C, which were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, and incubated with the appropriate medium. Inhibition of cell death was calculated as a percentage of untreated cells.

Mice, inoculations, and acute LD50 assay.

CD-1 mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratory (Portage, Mich.) and maintained in a biocontainment room according to Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care standards. Five- to 6-week-old CD-1 mice were anesthetized intraperitoneally with pentobarbital and inoculated in the right cerebral hemisphere with 30 μl of virus. The 50% lethal dose (LD50) was determined in i.c.-inoculated mice using four adult mice per 10-fold dilution of virus. Endpoints were calculated by the method of Reed and Muench (36).

Histology and fluorescent-antibody staining.

Control and infected CD-1 mice (GDVII, n = 5; GD-A745, n = 12) were anesthetized and sacrificed by perfusion with PBS and 10% buffered formalin. Tissues were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, cut into 6-μm-thick sections, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For immunofluorescence, brains and spinal cords (GDVII, n = 5; GD-A745, n = 15) were quick frozen, cut into 5-μm-thick sections with a cryostat, air dried, fixed in acetone for 10 min at 24°C, and stained for TMEV antigens with polyclonal rabbit anti-BeAn serum and goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G-FITC as described previously (29).

Statistics.

Comparisons of values between two groups were analyzed by the paired t test.

RESULTS

GDVII virus adaptation to proteoglycan-deficient CHO cells.

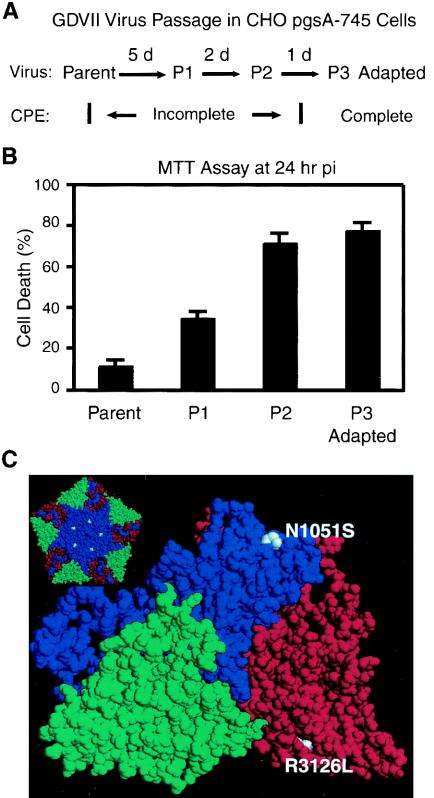

To generate a high-neurovirulence TMEV that did not require binding to HS for infection, GDVII virus was passed in CHO mutant pgsA-745 cells deficient in xylosyl transferase (1), an enzyme required for attachment of the tetrasaccharide linker to the protein core and for glycosaminoglycan synthesis. Unlike the complete cytopathic effect (CPE) at 48 h postinfection (p.i.) observed in parental CHO cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10, CPE of the passed virus was observed only after day 3 p.i. and did not even progress to completion by day 5 p.i. at the same MOI. Two additional passages were required for >90% CPE to develop within 24 h, i.e., at passage 3 (P3) (Fig. 1A), and a stock of the adapted virus, designated GD-A745, was prepared for further use. GDVII adaptation to pgsA-745 cells was progressive, as measured by cell death at 24 h p.i. in each passage (Fig. 1B). While GD-A745 and the GDVII parent showed essentially the same titers (3.0 × 108 and 3.5 × 108 PFU/ml, respectively), plaque size was significantly (P < 0.001) larger in the adapted virus (3.63- ± 0.6-mm diameter; n = 31) than the parent (2.78- ± 0.8-mm diameter; n = 31). Sequencing of the complete GD-A745 genome identified only two point mutations in the capsid, N1051S and R3126L (Fig. 1C). N1051S is on the first corner of VP1 and exposed on the virion surface, while the R3126L mutation, resulting in loss of a positive charge, is in the VP3 βE strand and is also exposed on the virion surface.

FIG. 1.

Adaptation of GDVII virus to proteoglycan-deficient pgsA-745 cells. (A) pgsA-745 cells were infected with GDVII (MOI, 10) and allowed to progress to maximal CPE, which was reached at 5 days p.i. (P1). Lysates were passed twice more in pgsA-745 cells until ∼90% CPE was obtained within 24 h p.i. (P3). (B) CPEs induced at different passages determined in a cell death assay, with cell death calculated as a percentage (mean plus standard deviation of four independent experiments) of uninfected controls. (C) Mutations in GD-A745 on the GDVII asymmetric icosahedral unit (protomer) in a space-filling model generated with RasMol software. The GD-A745 pentamer is shown in the inset.

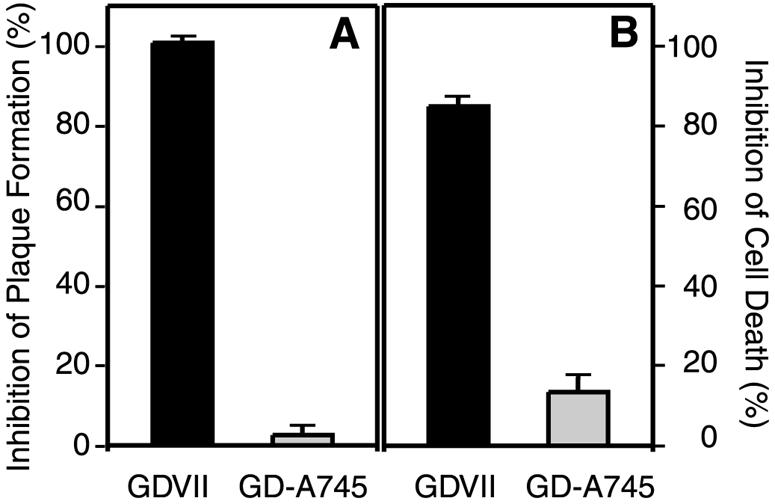

GD-A745 does not use HS for infection.

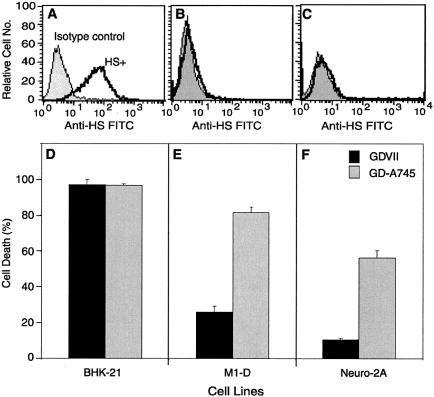

Soluble HS (100 μg/ml) completely inhibited parental GDVII virus plaque formation (3 days p.i.) (Fig. 2A) and CPE after infection at an MOI of 10 (24 h p.i.) in BHK-21 cells (Fig. 2B), consistent with the use of HS by this virus as a coreceptor (35). In contrast, GD-A745 virus plaque formation and cell death were minimally inhibited under the same conditions (Fig. 2). Flow cytometry using an anti-HS monoclonal antibody (MAb) (F58-10E4) previously shown to partially inhibit GDVII infection in BHK-21 cells (35) indicated that murine M1-D macrophages and murine Neuro 2A neuroblastoma cells were also deficient in the HS epitope recognized by this MAb (11) (Fig. 3B and C). GD-A745 produced significantly (P < 0.0005) more CPE than the parental GDVII in the HS epitope-negative cells (Fig. 3E and F), whereas equivalent levels of CPE were observed in BHK-21 cells (Fig. 3D). These results indicate that GD-A745 does not use HS for infection and that entry reflects either the use of another coreceptor or the ability of the virus to access the protein entry receptor directly.

FIG. 2.

Soluble HS does not competitively inhibit GD-A745 virus. GDVII (solid bars) and GD-A745 (shaded bars) viruses were incubated with either PBS or HS (100 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C before adsorption to BHK-21 cells. Inhibition of plaque formation (A) and cell death (B) by soluble HS were calculated as percentages (mean plus standard deviation of three independent experiments) of uninfected cells and mock-infected controls.

FIG. 3.

Efficiency of GD-A745 infection of mammalian cells correlates with cell surface HS expression. Cell surface expression of HS on BHK-21 (A), M1-D (B), and Neuro-2A (C) cells was detected by flow cytometry (see Materials and Methods) using the anti-HS MAb F58-10E4. Infection of BHK-21 (D), M1-D (E), and Neuro-2A (F) cells by GDVII and GD-A745 viruses (MOI, 10) was determined in a cell death assay. Percent cell death (mean plus standard deviation of four independent experiments) was calculated using uninfected cells as controls.

GD-A745 has a replicative advantage in CHO cells.

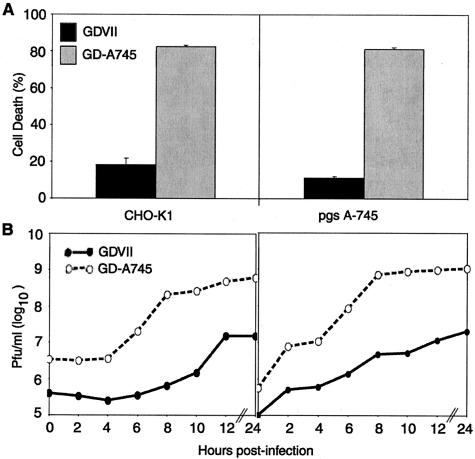

Parental CHO cells are relatively resistant to infection by GDVII virus, even at MOIs as high as 50, and express only low levels of HS on the cell surface (35). Analysis of CHO compared to pgsA-745 cells infected at an MOI of 10 showed that while GDVII and GD-A745 bound CHO cells with similar efficiencies, GD-A745 expressed 20-fold-higher levels of intracellular virus antigen at 24 h p.i. as assessed by flow cytometry (data not shown). Consistent with that finding, CPE for GD-A745 was fourfold higher than for GDVII virus in these cell lines (Fig. 4A). Single-step growth experiments further demonstrated the contrasting infection profiles of the viruses (Fig. 4B); GD-A745 infection was characterized by higher titers postadsorption (0 h), more rapid replication, and higher virus yields per cell in CHO cells than in parental GDVII (500 versus 20 PFU/cell), apparently due to more efficient entry. The more rapid logarithmic growth of GD-A745 in pgsA-745 cells raises the possibility that HS may even hinder GD-A745 entry into CHO cells.

FIG. 4.

Infection of CHO cells by GDVII virus is limited by lower HS expression. (A) CHO cells were infected with either GDVII or GD-A745 at an MOI of 10. The CPE was determined by a cell death assay 24 h p.i. and is expressed as a percentage (mean plus standard deviation of four independent experiments) of uninfected controls. (B) Single-step growth kinetics of both viruses in CHO cells. Cells were infected (MOI, 10), and the lysates were harvested at 2-h intervals (0 to 12 h) and at 24 h postadsorption. Virus yields were quantitated by plaque assays in duplicate on BHK-21 cells.

GD-A745 virus does not use sialic acid as a coreceptor.

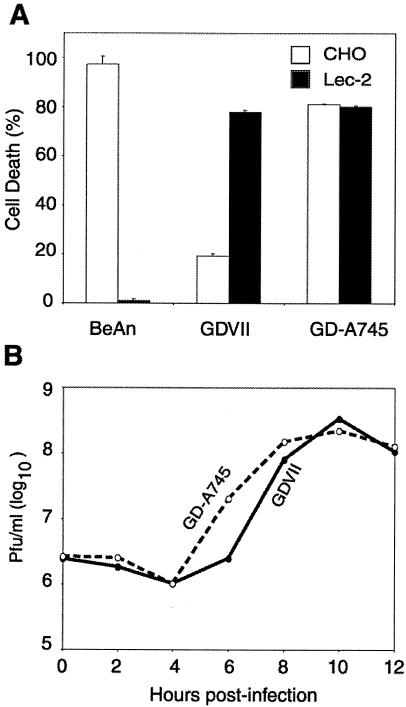

Receptor use by TMEV was further analyzed in CHO and sialic acid-deficient CHO (Lec-2) cells infected with GDVII, GD-A745, or a low-neurovirulence TMEV strain (BeAn), which uses sialic acid as a coreceptor. BeAn virus did not produce CPE in Lec-2 cells, whereas GDVII virus infection was associated with a fourfold-higher extent of CPE in Lec-2 than in CHO cells (Fig. 5A). In contrast, GD-A745-induced CPEs were comparable in the two cell lines (Fig. 5A). Thus, GD-A745 did not appear to use sialic acid for entry, consistent with failure of the sialic acid mimic siallylactose to inhibit CPE in BHK-21 cells (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Sialic acid-deficient CHO (Lec-2) cells are equally permissive to GDVII and GD-A745 infection. (A) Infection of Lec-2 cells by GDVII and GD-A745 (MOI, 10) was analyzed by a cell death assay at 24 h p.i. Percent cell death (mean plus standard deviation of four independent experiments) was calculated using uninfected cells as controls. (B) Single-step growth kinetics were compared using lysates of infected Lec-2 cells harvested at 2-h intervals (0 to 12 h) and at 24 h postadsorption. Virus yields were quantitated by plaque assay in duplicate on BHK-21 cells.

In a single-step growth experiment in Lec-2 cells, GDVII and GD-A745 viruses were similar in attachment, eclipse, and virus yields (1,000 PFU/cell), although GD-A745 had a slightly higher rate of replication (Fig. 5B). These results, together with single-step growth kinetics in CHO cells (Fig. 4B), indicate that there is no block in the viral life cycle after entry in CHO cell derivatives. Instead, entry is governed by the expression or lack of expression of HS.

GD-A745 acute CNS virulence is attenuated and the disease phenotype is changed.

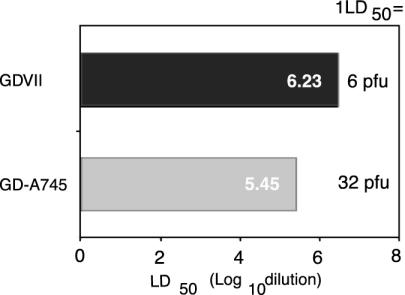

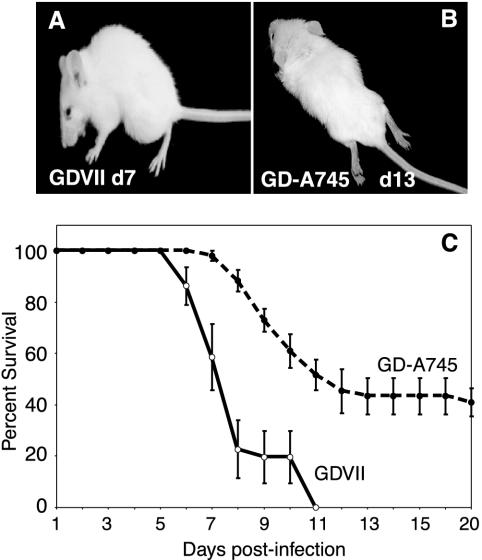

Disease pathogenesis was analyzed in 5- to 6-week-old CD-1 mice inoculated i.c. with 100 PFU of GDVII or GD-A745. LD50 determinations indicated that GD-A745 virus was fivefold less virulent than GDVII virus (LD50s, 32 and 6 PFU, respectively) (Fig. 6). GDVII virus-infected mice developed signs of encephalitis by day 5 p.i. (hunched posture, circling, ruffled fur, and inactivity), and all animals died by days 9 to 11 p.i. (Fig. 7A and C). In contrast, GD-A745 virus-infected mice developed flaccid-limb paralysis without signs of encephalitis, and ∼40% of the mice survived to day 20 p.i. (Fig. 7B and C). All mice infected with 1,000 PFU of GD-A745 virus died by day 15 p.i. with flaccid paralysis but without signs of encephalitis (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

GD-A745 virus is attenuated in neurovirulence in vivo. Adult CD1 mice were inoculated i.c. with serial 10-fold dilutions of either parental GDVII or adapted GD-A745 virus (four mice per dilution) to determine the LD50. The results are representative of two experiments.

FIG. 7.

GD-A745 is attenuated in acute CNS virulence and induces an altered disease phenotype. (A) GDVII virus-induced encephalitis (hunched appearance and ruffled fur). (B) GD-A745 virus-induced poliomyelitis (flaccid-limb paralysis). (C) Percent survival (mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments) of mice inoculated with GDVII or GD-A745 and followed for 20 days.

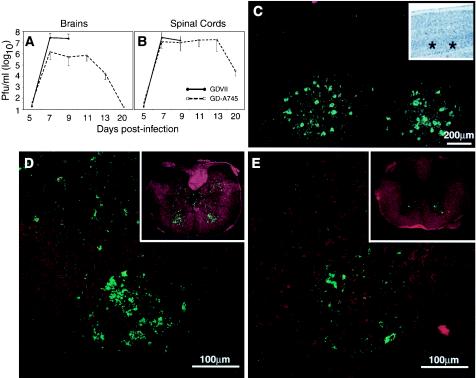

Virus growth in the brain peaked on day 7 p.i. in mice infected with 100 PFU of either virus; however, titers were ∼20-fold higher in GDVII virus- than in GD-A745 virus-infected mice on days 7 and 9 p.i. (Fig. 8A). Initial kinetics of virus growth in the spinal cords of mice infected with either virus were similar, with peak titers on day 7 p.i. (Fig. 8B). Note that spinal cord virus titers plateaued after day 7 p.i. in GD-A745-infected mice, in contrast to brains, where the titers steadily declined.

FIG. 8.

Attenuated neurovirulence of GD-A745 in mice. (A and B) Virus growth kinetics in brains and spinal cords of GDVII- or GD-A745-infected mice (mean ± standard deviation; n = 3). (C) Two clusters of virus antigen-containing neurons in the lowest cytoarchitectonic layer of the parietal neocortex in a GDVII-infected mouse on day 7 p.i. Virus antigen was detected with indirect immunofluorescent staining using a polyclonal rabbit antibody to TMEV and goat anti-rabbit-FITC and was counterstained with Evans blue dye. Such clusters of infected cells are typical of those found scattered throughout the neocortex; in contrast, no infected cells were seen in the cerebral hemispheres of GD-A745-infected mice. The inset shows the locations (asterisks) in the neocortex in a hematoxylin- and eosin-stained section. (D) Virus antigen in cells, including anterior horn cells, in the anterior gray matter of a GDVII-infected mouse on day 7 p.i. The inset is the entire coronal section, showing many infected cells in the posterior, as well as the anterior, gray matter. (E) Virus antigen-containing cells, including anterior horn cells, in the anterior gray matter of a GD-A745-infected mouse on day 7 p.i. The inset shows the entire coronal section with infected cells only in the anterior gray matter.

Immunofluorescent staining for virus antigen in the brain revealed numerous focal areas of positive cells (largely neurons by morphology) in the neocortex, hippocampal pyramidal cell layer, and brainstem in GDVII-infected mice (Fig. 8C), but there were at most only rare positive cells in the brainstem and none in the cerebral hemispheres in GD-A745-infected mice on days 7 to 9 p.i. In the spinal cords of mice infected with GDVII virus, there were large numbers of virus antigen-containing neurons in both the anterior and posterior gray matter, whereas infected neurons, generally fewer in numbers, were observed only in the anterior gray matter of GD-A745-infected mice (Fig. 8D and E). Histopathology sections revealed consistently more severe pathological changes (neuronophagia, astrocytosis, microglial proliferation, and mononuclear cell infiltration in perivascular sites and leptomeninges) in the neocortex, hippocampus, and brainstem in GDVII- than in GD-A745-infected mice on days 7 to 9 p.i. (data not shown). However, in spinal cord gray matter, such changes were more severe in GD-A745- than GDVII-infected mice (data not shown). Poliomyelitis in GD-A745 spinal cords progressed between days 9 and 13 p.i.

Together, these results indicate that GDVII, no longer using HS as a coreceptor, shows attenuated neurovirulence and changed cell tropism, limiting infection to neurons in the anterior gray matter of the spinal cord. Attenuation of infection in the brain allowed host survival past day 11 (the longest survival of parental-virus-infected mice) and expression of clinical poliomyelitis in GD-A745-infected mice. All of the analyses described above were also carried out using GDVII adapted to growth in another proteoglycan-deficient cell line, pgsD-677, which lacks only HS but not other glycosaminoglycans. The adapted GD-D677 virus was virtually identical to GD-A745 with respect to capsid mutations, virus yields in BHK-21 and Lec-2 cells, and attenuation of neurovirulence in mice (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we show that the use of HS as an attachment factor by GDVII virus affects the efficiency of infection in CHO cells and is linked to neurovirulence in mice. Previously, we found that binding of high-neurovirulence GDVII virus to mammalian cells involves sequential attachment to two components: HS, a carbohydrate coreceptor, and another receptor, possibly the protein entry receptor. The restoration of infectivity in HS-deficient CHO cells by neuraminidase treatment and removal of cell surface sialic acid (35) suggested that direct access to another receptor required for infection was hindered by sialic acid.

GDVII virus adapted to growth in proteoglycan-deficient cells completely ceased using HS as a coreceptor (Fig. 1 to 3). Comparison of GDVII and the GD-A745 adapted viruses in vitro and in vivo highlighted several aspects of the interaction of GDVII virus with its receptors for infection: (i) the low level of HS on CHO cells is a major block to parental GDVII replication (20 PFU/cell at 24 h p.i.), which was overcome by the adapted virus (500 PFU/cell at 24 h p.i.) (Fig. 4); (ii) the absence of cell surface sialic acid on CHO-derived Lec-2 cells compensated for this block (Fig. 5), consistent with our previous finding that neuraminidase treatment of proteoglycan-deficient cells facilitated infection by allowing direct access to another receptor; and (iii) the loss of use of HS by GD-A745 for entry led to attenuated neurovirulence and altered virus tropism from neurons in the brain to neurons in the spinal cord, resulting in a poliomyelitic instead of an encephalitic phenotype (Fig. 6 to 8).

Viruses that use HS for attachment and entry may interact with HS through heparin-binding domains (HBDs) consisting of at least two major HBD consensus motifs (4). Analysis of the 12 TMEV gene products revealed a putative HBD, YKKMKV, in VP1. The amino acids YKKMKV are conserved in all high- and low-neurovirulence TMEV (33) and are located in the VP1 C terminus, the highest elevation on the virion surface (31); however, low-neurovirulence TMEV do not use HS as a coreceptor, so HS binding is probably conformation- and not HBD-dependent. Interaction of viruses, such as foot and mouth disease virus and Sindbis virus, with HS (9, 22) is also thought to be conformational in nature, despite the presence of HBDs. The detection of only two mutations in the GD-A745 genome and none in the potential HBD supports this thesis.

One of the mutations in GD-A745, R3126L, is a leucine residue in all low-neurovirulence TMEV and is responsible for loss of a positive charge, whereas in high-neurovirulence TMEV, this residue is arginine. The substitution in GD-A745 may also have affected exposure of existing HS-interacting motifs, since arginines reportedly bind more tightly to glycosaminoglycans (15), which might underlie loss of HS binding by GD-A745. The effect of the N1051S substitution is less clear but might be more global, altering the conformation of the capsid and, in turn, the virus-protein entry receptor interaction. Recently, Jnaoui et al. (20) adapted GDVII virus to CHO cells that express low levels of HS, giving rise to a virus that produced complete CPE at a low MOI in CHO cells. N1051S was one of five substitutions in the capsid of their adapted virus and was believed to be solely responsible for the adaptation of the virus. When N1051S was introduced as a ∼0.5-kb restriction endonuclease fragment from their adapted virus into the wild-type GDVII genome, the virus grew more efficiently in CHO cells (20). However, in contrast to our results, their adapted virus was completely attenuated and did not produce disease in mice infected with 104 PFU. Since relatively few mice were infected and they were observed for only 10 days p.i. in that study, the later-onset paralysis that we observed may have been overlooked.

HS is a branched polysaccharide chain composed of a repeated disaccharide sequence. Multiple chains are covalently linked to a protein core, resulting in a proteoglycan. Sulfate groups are N and O linked to the sugar residues, conferring a net negative charge on the HS molecule. The positions at which sulfates and other moieties (N-acetyl groups) are linked determine the large diversity of HS found in nature (34). Binding of viruses to HS can involve far more than simple nonspecific ionic interactions, i.e., binding depends not only on the electrostatic interactions between positively charged amino acids on the proteins and the negative HS clusters but also on the specificity of side chains, as demonstrated for herpes simplex virus (6, 14, 30, 40). Moreover, the monosaccharide sequences of HS from different tissues are distinct, indicating that HS has tissue-specific biological functions. These structural distinctions in HS might also underlie the tissue specificity of viral binding, thereby regulating cell tropism. The absence of the HS F58-10E4 epitope (which contains an N-sulfate moiety) in macrophages and neuroblastoma cells limited GDVII infection in our study (Fig. 3), suggesting a requirement for a specific HS structure for interaction with high-neurovirulence TMEV. Since GD-A745 did not use HS for entry, this structural requirement was no longer limiting for the virus.

Our finding that propagation of GDVII virus in proteoglycan-deficient cells leads to loss of HS use for entry and to attenuation of virulence in vivo contrasts with most other reports indicating the converse, i.e., that adaptation to cells results in the gain of HS use for entry and attenuation of virulence (Table 1). In these cases, the route of inoculation was peripheral (to the CNS) (Table 1), and HS binding may have resulted in more rapid clearance of viremia (2, 3). Two exceptions are a recombinant Sindbis virus and a naturally occurring mutant of murine leukemia virus, both of which became more neurovirulent after gaining a positive charge and HS binding ability (18, 25), a phenotype similar to that of the parental GDVII virus. In both these instances (Table 1), virus was inoculated i.c. into the animal host (18, 25). This points to a greater role for HS coreceptor use and cell tropism after i.c. inoculation. Because there is an indication of regional differences in expression of HS in the CNS (11, 12), it is possible that GDVII infection of distinct sets of neurons, e.g., those in the lower layers of the neocortex, the hippocampal pyramidal layer, the brainstem, and the posterior spinal cord gray matter, is more dependent on specific HS binding than infection of anterior horn cells. Other uninfected neurons may not express HS. Further studies to precisely elucidate the role of HS use in GDVII infection in specific brain regions will help to address this possibility.

TABLE 1.

Relationship between HS use for cell entry in vitro and viral pathogenesis in vivo

| Virusa (reference) | Derivation | Mutation | Charge change | HS useb | Effect on disease

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Routec | Virulence | |||||

| Flaviviridae | E protein | |||||

| TBEV (10) | BHK-21 passed | D483G | + | Y | S.c. | Attenuated |

| TBEV (32) | BHK-21 passed | E201K, E122G | + | Y | S.c. | Attenuated |

| SFV (16) | SK26 passed | S476R | + | Y | I.n. | No change |

| JEV (24) | SW13 passed | E306K | + | Y | F.p. | Attenuated |

| MEV (23) | SW13 passed | D390K | + | Y | F.p. | Attenuated |

| Togaviridae | E2 protein | |||||

| SV (22) | BHK-21 passed | S1R | + | Y | S.c. | Attenuated |

| SV (25) | Recombinant | D218K | + | Y | I.c. | More virulent |

| RRV (13) | CEF passed | D218K | + | Y | S.c. | Attenuated |

| VEE (2) | BHK-21 passed | E/T→Kd | + | Y | F.p. | Attenuated |

| Retroviridae | Env | |||||

| PVC-MuLV (18) | Rat passed | E116G, E129K | + | Y | I.c. | More virulent |

| Picornaviridae | Capsid | |||||

| FMDV (41) | BHK-21 passed | K1083E | − | Y | I.d. | Attenuated |

| FMDV (38) | CHO-K1 passed | H3056R | + | N | I.d.; lin | Attenuated |

| GDVII viruse | pgs-A745 passed | R3126L, N1051S | − | N | I.c. | Attenuated |

TBEV, tick-borne encephalitis virus; SFV, swine fever virus; JEV, Japanese encephalitis virus; MEV, Murray Valley encephalitis virus; SV, Sindbis virus; RRV, Ross River virus; VEE, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus; MuLV, murine leukemia virus strain PVC-211; FMDV, foot-and-mouth disease virus.

Y, yes; N, no.

S.c., subcutaneous; I.n., intranasal; F.p., footpad; I.d., intradermal; lin, inoculated onto tongue.

Multiple residues involved.

Present study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elisabeth Wilson for technical assistance and Mary Lou Jelachich for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by NIH grant NS21913.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bai, X., G. Wei, A. Sinha, and J. D. Esko. 1999. Chinese hamster ovary cell mutants defective in glycosaminoglycan assembly and glucuronosyltransferase I. J. Biol. Chem. 19:13017-13024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernard, K. A., W. B. Klimstra, and R. E. Johnston. 2000. Mutations in the E2 glycoprotein of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus confer heparan sulfate interaction, low morbidity, and rapid clearance from blood of mice. Virology 276:93-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrnes, A. P., and D. E. Griffin. 2000. Large-plaque mutants of Sindbis virus show reduced binding to heparan sulfate, heightened viremia, and slower clearance from the circulation. J. Virol. 74:644-651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardin, A. D., and H. J. R. Weintraub. 1989. Molecular modeling of protein-glycosoaminoglycan interactions. Arteriosclerosis 9:21-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denizot, F., and R. Lang. 1986. Rapid colorimetric assay for cell growth and survival. Modifications to the tetrazolium dye procedure giving improved sensitivity and reliability. J. Immunol. Methods 89:271-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feyzi, E., E. Trybala, T. Bergstrom, U. Lindahl, and D. Spillman. 1997. Structural requirement of heparan sulfate for interaction with herpes simplex virus type 1 virions and isolated glycoprotein C. J. Biol. Chem. 272:24850-24857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fotiadis, C., D. R. Kilpatrick, and H. L. Lipton. 1991. Comparison of the binding characteristics to BHK-21 cells of viruses representing the two Theiler's virus neurovirulence groups. Virology 182:365-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedmann, A., and H. L. Lipton. 1980. Replication of GDVII and DA strains of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus in BHK 21 cells: an electron microscopic study. Virology 101:389-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fry, E. E., S. M. Lea, T. Jackson, J. W. Newman, F. M. Ellard, W. E. Blakemore, R. Abu Ghazaleh, A. Samuel, A. M. Q. King, and D. I. Stuart. 1999. The structure and function of a foot-and-mouth disease-virus oligosaccharide receptor complex. EMBO J. 18:543-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goto, A., D. Hayasaka, K. Yoshii, T. Mizutani, H. Kariwa, and I. Takashima. 2003. A BHK-21 cell culture-adapted tick-borne encephalitis virus mutant is attenuated for neuroinvasiveness. Vaccine 21:4043-4051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guido, D., X. M. Bai, B. Van Der Schueren, J.-J. Cassiman, and H. Van Den Berghe. 1992. Developmental changes in heparan sulfate expression: in situ detection with mAbs. J. Cell Biol. 119:961-975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartmann, U., and P. Maurer. 2001. Proteoglycans in the nervous system—the quest for functional roles in vivo. Matrix Biol. 20:23-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heil, M. L., A. Albee, J. H. Strauss, and R. J. Kuhn. 2001. An amino acid substitution in the coding region of the E2 glycoprotein adapts Ross River virus to utilize heparan sulfate as an attachment moiety. J. Virol. 75:6303-6309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herold, B. C., S. I. Gerber, B. J. Belval, A. M. Siston, and N. Shulman. 1996. Differences in the susceptibility of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 to modified heparin compounds suggest serotype differences in viral entry. J. Virol. 70:3461-3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hileman, R. E., J. R. Fromm, J. M. Weiler, and R. J. Linhardt. 1998. Glycosaminoglycan-protein interactions: definition of consensus sites in glycosaminoglycan binding proteins. BioEssays 20:156-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hulst, M. M., H. G. van Gennip, A. C. Vlot, E. Schooten, A. J. de Smit, and R. J. Moormann. 2001. Interaction of classical swine fever virus with membrane-associated heparan sulfate: role for virus replication in vivo and virulence. J. Virol. 75:9585-9595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jelachich, M. L., C. Brumlage, and H. L. Lipton. 1999. Differentiation of M1 myeloid precursor cells into macrophages results in binding and infection by Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) and apoptosis. J. Virol. 73:3227-3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jinno-Oue, A., M. Oue, and S. K. Ruscetti. 2001. A unique heparin-binding domain in the envelope protein of the neuropathogenic PVC-211 murine leukemia virus may contribute to its brain capillary endothelial cell tropism. J. Virol. 75:12439-12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jnaoui, K., and T. Michiels. 1999. Analysis of cellular mutants resistant to Theiler's virus infection: differential infection of L929 cells by persistent and neurovirulent strains. J. Virol. 73:7248-7254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jnaoui, K., M. Minet, and T. Michiels. 2002. Mutations that affect the tropism of DA and GDVII strains of Theiler's virus in vitro influence sialic acid binding and pathogenesis. J. Virol. 76:8138-8147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kilpatrick, D. R., and H. L. Lipton. 1991. Predominant binding of Theiler's viruses to a 34-kilodalton receptor protein on susceptible cell lines. J. Virol. 65:5244-5249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klimstra, W. B., K. D. Ryman, and R. E. Johnston. 1998. Adaptation of Sindbis virus to BHK cells selects for use of heparan sulfate as an attachment receptor. J. Virol. 72:7357-7366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, E., and M. Lobigs. 2000. Substitutions at the putative receptor-binding site of an encephalitic flavivirus alter virulence and host cell tropism and reveal a role for glycosaminoglycans in entry. J. Virol. 74:8867-8875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, E., and M. Lobigs. 2002. Mechanism of virulence attenuation of glycosaminoglycan-binding variants of Japanese encephalitis virus and Murray Valley encephalitis virus. J. Virol. 76:4901-4911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, P., R. Knight, J. M. Smit, J. Wilschut, and D. E. Griffin. 2002. A single mutation in the E2 glycoprotein important for neurovirulence influences binding of Sindbis virus to neuroblastoma cells. J. Virol. 76:6302-6310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehrich, J. R., B. G. W. Arnason, and F. H. Hochberg. 1976. Demyelinating myelopathy in mice induced by the DA virus. J. Neurol. Sci. 29:149-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Libbey, J. E., I. J. McCright, I. Tsunoda, Y. Wada, and R. S. Fujinami. 2001. Peripheral nerve protein, PO, as a potential receptor for Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus. J. Neurovirol. 7:97-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipton, H. L. 1975. Theiler's virus infection in mice: an unusual biphasic disease process leading to demyelination. Infect. Immun. 11:1147-1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipton, H. L., G. Twaddle, and M. L. Jelachich. 1995. The predominant virus antigen burden is present in macrophages in Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)-induced demyelinating disease. J. Virol. 69:2525-2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, J., Z. Shriver, R. M. Pope, S. C. Thorp, M. B. Duncan, R. J. Copeland, C. S. Raska, K. Yoshida, R. J. Eisenberg, G. Cohen, R. J. Linhardt, and R. Sasisekharan. 2002. Characterization of a heparan sulfate octasaccharide that binds to herpes simplex type 1 glycoprotein D. J. Biol. Chem. 277:33456-33467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo, M., K. S. Toth, L. Zhou, A. Pritchard, and H. L. Lipton. 1996. The structure of a highly virulent Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (GDVII) and implications for determinants of viral persistence. Virology 220:246-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mandl, C. W., H. Kroschewski, S. L. Allison, R. Kofler, H. Holzmann, T. Meixner, and F. X. Heniz. 2001. Adaptation of tick-borne encephalitis virus to BHK-21 cells results in the formation of multiple heparan sulfate binding sites in the envelope protein and attenuation in vivo. J. Virol. 75:5627-5637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michiels, T., N. Jarousse, and M. Brahic. 1995. Analysis of the leader and capsid coding regions of persistent and neurovirulent strains of Theiler's virus. Virology 214:550-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perrimon, N., and M. Bernfield. 2000. Specificities of heparan sulphate proteoglycans in developmental processes. Nature 404:725-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reddi, H. V., and H. L. Lipton. 2002. Heparan sulfate mediates infection of high-neurovirulence Theiler's viruses. J. Virol. 76:8400-8407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reed, L. J., and H. A. Muench. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 27:493-497. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rozhon, E. J., J. D. Kratochvil, and H. L. Lipton. 1983. Analysis of genetic variation in Theiler's virus during persistent infection in the mouse central nervous system. Virology 128:16-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sa-Carvalho, D., E. Rieder, B. Baxt, R. Rodarte, A. Tanuri, and P. W. Mason. 1997. Tissue culture adaptation of foot-and-mouth disease virus selects viruses that bind to heparin and are attenuated in cattle. J. Virol. 71:5115-5123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shah, A. H., and H. L. Lipton. 2002. Low-neurovirulence Theiler's viruses use sialic acid moieties on N-linked oligosaccharide structures for attachment. Virology 304:443-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shukla, D., J. Liu, P. Blaiklock, N. W. Shworak, X. Bai, J. D. Esko, G. H. Cohen, R. D. Eisenberg, and P. G. Spear. 1999. A novel role for 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate in herpes simplex virus 1 entry. Cell 99:13-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao, Q., J. M. Pacheco, and P. W. Mason. 2003. Evaluation of genetically engineered derivatives of a Chinese strain of foot-and-mouth disease virus reveal a novel cell-binding site which functions in cell culture and in animals. J. Virol. 77:3269-3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou, L., Y. Luo, Y. Wu, J. Tsao, and M. Luo. 2000. Sialylation of the host receptor may modulate entry of demyelinating persistent Theiler's virus. J. Virol. 74:1477-1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]