Abstract

Stress-induced cardiomyopathy is a syndrome of transient cardiac dysfunction with no clear pathophysiology. It is thought to be secondary to catecholamine surge. The mechanism by which catecholamine can induce transient cardiac dysfunction is unknown. We present a case of a patient who developed stress-induced cardiomyopathy after she was administered norepinephrine due to a nursing error.

Stress-induced cardiomyopathy (also known as takotsubo cardiomyopathy, TC) is a syndrome of transient cardiac dysfunction precipitated by intense emotional or physical stress. It has been recognized in Japan since 1991 (1). The prevalence of TC in the general population is estimated to be between 1.7% and 2.2% in patients who present with suspected acute coronary syndrome. It is characterized by acute chest pain, electrocardiographic changes, and elevated cardiac biomarkers in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease. It can be classified into a left ventricular apical ballooning variant (most common), an inverted or reverse variant (basal akinesis with hyperdynamic apex), and a midventricular variant. We present a patient who developed TC after receiving a norepinephrine injection.

CASE REPORT

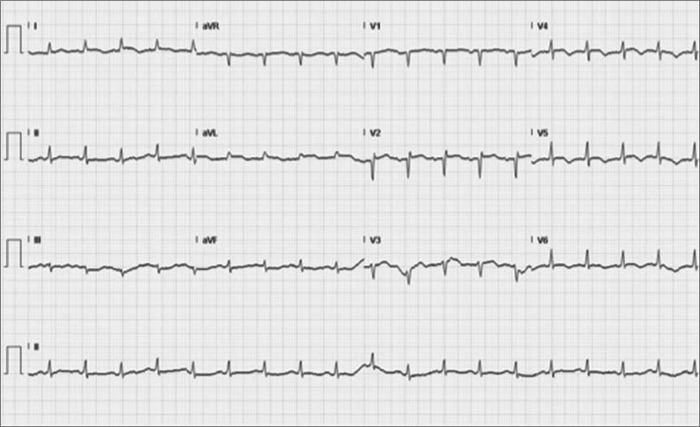

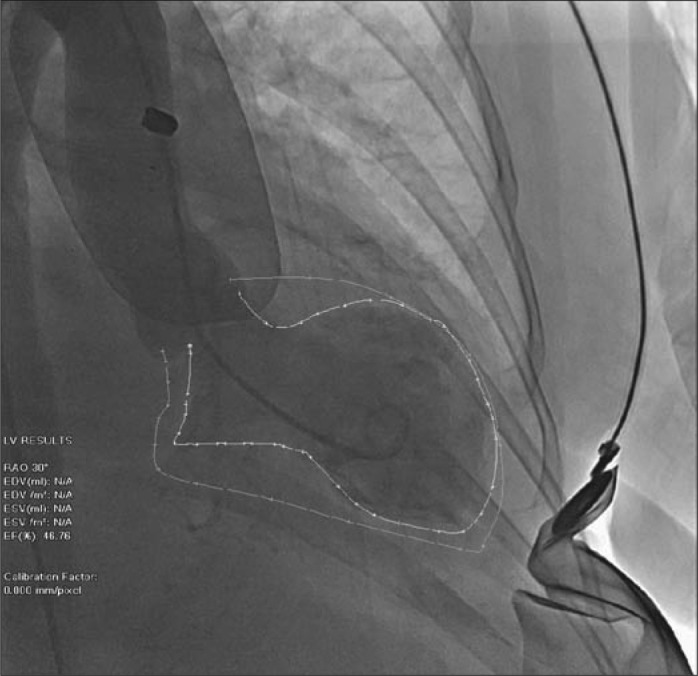

A 76-year-old woman with hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and diverticulosis presented with bright red rectal bleeding. On admission, she was hemodynamically stable. She was found to have normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 7.8 g/dL. Two units of packed red blood cells with furosemide were ordered. After the patient received blood, norepinephrine (Levophed) 4 mg intravenously was given instead of furosemide 40 mg due to a nursing error. Soon after that, the patient started complaining of chest pain with dyspnea and was in acute distress with tachypnea and expiratory wheezing. An electrocardiogram showed new ST segment and T wave changes in the precordial leads (Figure 1). Her troponin T level was 0.44 ng/mL; creatinine kinase, 131 ng/mL; and creatinine kinase–myocardial band, 6.9 ng/mL. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed severely depressed left ventricular systolic function with an ejection fraction of 25% to 29% with apical wall akinesis and hypokinesis of anterior, anteroseptal, and anterolateral walls. Coronary angiography showed no evidence of significant obstructive coronary artery disease. A left ventriculogram showed mildly depressed left ventricular systolic function and an ejection fraction of 45%, with evidence of apical ballooning (Figure 2). The diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy was made. The patient was treated with beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and aldosterone antagonist for heart failure symptoms. She improved over time and was discharged home. A transthoracic echocardiogram after 6 months showed an ejection fraction of 50% to 55%.

Figure 1.

ECG showing ST segment and T wave changes.

Figure 2.

Left ventriculogram showing apical ballooning.

DISCUSSION

The left ventricular dysfunction that occurs with stress-induced cardiomyopathy is thought to be secondary to catecholamine surge brought on by intense psychological or physical stress. Much of the evidence for this comes from observational and case-control studies that have found an association between elevated catecholamine levels and disease onset. The mechanism by which catecholamine can induce transient left ventricular dysfunction is unclear. It is possible that high doses of catecholamine are directly toxic to myocardial cells. This is supported by histological findings from animal studies and autopsy findings from TC patients that document myofibril degeneration, contraction band necrosis, and leukocyte infiltration (2). Molecular studies in cultured cardiocytes have shown that high doses of epinephrine are directly toxic to the cells. This results in a significant rise in cyclic adenosine monophosphate and calcium levels that trigger the formation of free oxygen radicals, initiation of expression of stress response genes, and induction of apoptosis in a subset of cells (3, 4). Myocardial necrosis cannot explain the entire picture because most patients with TC regain full recovery of left ventricular function. It has been proposed that epinephrine may cause damage by inducing spasm of coronary macro- and microvasculature and/or stunning of cardiocytes directly because of cyclic adenosine monophosphate–mediated calcium overload (5).

About 80% of TC cases occur in postmenopausal women. Studies have shown that estrogen plays an important role in protecting the myocardium (6), possibly by downregulating beta-adrenergic receptors. Postmenopausal women lose this protection and are more vulnerable to the catecholamine surge that is associated with stress. There is a predominance of the apical ballooning variant. It was previously suggested that the apex of the heart is more sensitive to epinephrine due to a higher density of beta-adrenergic receptors in the cardiac apex versus the base (4).

In our case, the patient accidentally received a high dose of norepinephrine, which stimulates alpha and beta-1 adrenergic receptors and produces both positive ionotropic and vasodepressor effects. The patient developed the classic form of TC, and this case confirms the direct causal role of catecholamine in the pathophysiology of TC. In the past, several cases of iatrogenically induced TC have been reported. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of stress-induced cardiomyopathy secondary to iatrogenic norepinephrine injection.

References

- 1.Dote K, Sato H, Tateishi H, Uchida T, Ishihara M. [Myocardial stunning due to simultaneous multivessel coronary spasms: a review of 5 cases] J Cardiol. 1991;21(2):203–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Movahed A, Reeves WC, Mehta PM, Gilliland MG, Mozingo SL, Jolly SR. Norepinephrine-induced left ventricular dysfunction in anesthetized and conscious, sedated dogs. Int J Cardiol. 1994;45(1):23–33. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(94)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mann DL, Kent RL, Parsons B, Cooper G., IV Adrenergic effects on the biology of the adult mammalian cardiocyte. Circulation. 1992;85(2):790–804. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.2.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyon AR, Rees PS, Prasad S, Poole-Wilson PA, Harding SE. Stress (takotsubo) cardiomyopathy—a novel pathophysiological hypothesis to explain catecholamine-induced acute myocardial stunning. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5(1):22–29. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA, Baughman KL, Schulman SP, Gerstenblith G, Wu KC, Rade JJ, Bivalacqua TJ, Champion HC. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):539–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ueyama T, Hano T, Kasamatsu K, Yamamoto K, Tsuruo Y, Nishio I. Estrogen attenuates the emotional stress-induced cardiac responses in the animal model of tako-tsubo (ampulla) cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003;42(Suppl 1):S117–S119. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200312001-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]