Abstract

Infective endocarditis caused by Klebsiella species is rare, with most isolates being K. pneumoniae. We report the case of a 24-year-old intravenous drug user with newly diagnosed seminoma who developed K. oxytoca endocarditis. In addition to having K. oxytoca isolated from blood culture, cultures of that species were obtained from a retroperitoneal metastasis found on original presentation.

Infective endocarditis caused by Klebsiella species is a rare event, accounting for ≤1.2% cases of native valve endocarditis and up to 4.1% cases of prosthetic valve endocarditis (1). Of these, most are caused by K. pneumoniae. K. oxytoca is implicated in a significant minority of endocarditis cases caused by Klebsiella species, with only 5 reported cases (2–6). Most cases of K. oxytoca endocarditis occur in the elderly and are nosocomial. Here we report a case of community-acquired K. oxytoca in an intravenous drug abuser coinciding with newly diagnosed testicular cancer.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 24-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a 1-week history of fluctuating back and flank pain associated with fever. He first presented to an outside hospital after experiencing sudden-onset fever, chills, sweats, pallor, and dyspnea. At that visit, his temperature was 102°F, and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen without contrast revealed a large perinephric mass. The patient was sent to our facility for further management. In the emergency department, his blood pressure was 107/65 mm Hg; heart rate, 116 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/minute; and temperature, 97.7°F. Examination revealed right upper-quadrant tenderness on deep palpation and normal heart sounds with no murmur. His electrocardiogram was unremarkable. His hemoglobin was 12.2 g/dL; white blood cell count, 21,890/uL; alkaline phosphatase, 489 IU/L; aspartate aminotransferase, 199 IU/L; and alanine aminotransferase, 223 IU/L. Blood cultures were obtained and he was started on empiric vancomycin and meropenem for concerns of abscess and sepsis.

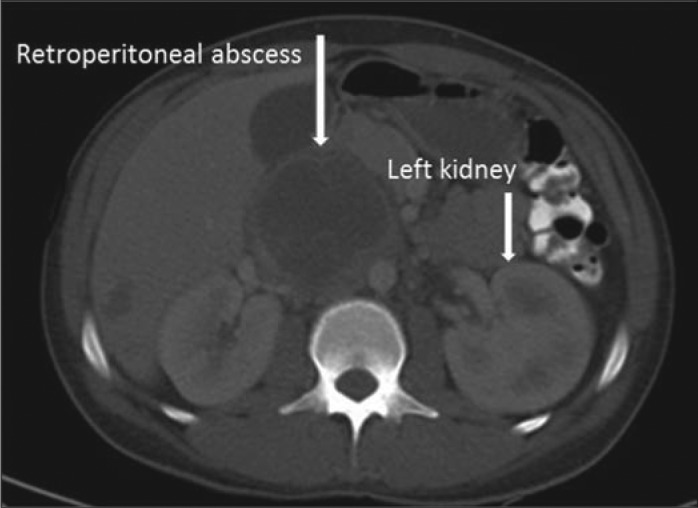

Repeat CT scan with contrast confirmed a peripherally enhancing right retroperitoneal mass measuring 6.4 × 7.5 × 9.1 cm with central hypodensity, suggestive of a necrotic lymph node and concerning for malignancy (Figure 1). A 12 French drainage catheter was placed, and 80 mL of purulent thick fluid was aspirated and submitted for gram stain, cultures, and cytology. An additional 160 mL of fluid was drained over the next 3 days.

Figure 1.

CT scan of the abdomen with contrast showing a retroperitoneal mass with abscess formation.

On follow-up, he reported having a 3-month history of an enlarging testicular mass. Following ultrasound concerning for malignancy, a radical right orchiectomy was performed showing classic seminoma, and further imaging staged the cancer as stage IIIB due to involvement of retroperitoneal and mediastinal lymph nodes. Meanwhile, blood cultures obtained in the emergency department as well as the outside hospital revealed growth of K. oxytoca. Vancomycin was discontinued.

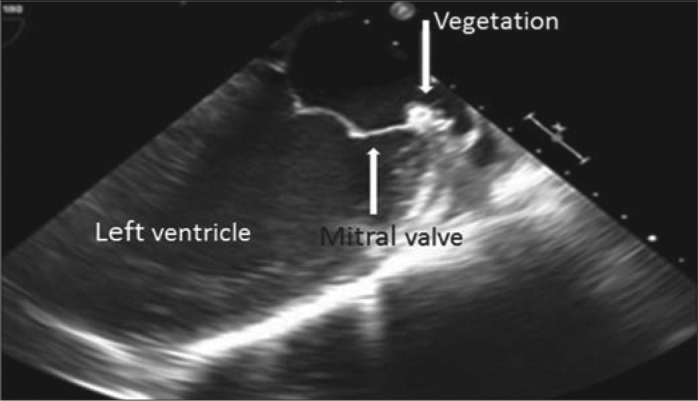

On hospital day 5, the patient's fever spiked to 102.9°F, and a holosystolic murmur most prominent over the apex was discovered. At this point, the patient admitted to injection of amphetamines diluted with tap water 1.5 weeks prior to admission. Transesophageal echocardiogram revealed 0.44 × 0.17 cm vegetation on the posterior mitral valve leaflet (Figure 2). In addition, CT-guided drainage of the retroperitoneal mass grew K. oxytoca and also contained malignant cells. Repeat CT scan 4 days after drain placement showed a reduction in mass size to 5.5 × 5.0 × 8.0 cm. The patient's fever abated, and follow-up blood cultures were negative. Intravenous meropenem was continued for 6 weeks with no complications. No follow-up echocardiogram was performed as the patient was lost to follow-up.

Figure 2.

Transesophageal echocardiogram revealing 0.44 × 0.17 cm vegetation on the posterior mitral valve leaflet.

DISCUSSION

This is a rare case of infective endocarditis of the mitral valve caused by K. oxytoca in an intravenous drug user. The diagnosis of infective endocarditis is based on the modified Duke criteria: one major criterion (intracardiac mass on the mitral valve) and three minor criteria (fever, positive blood culture, and predisposing intravenous drug use) (7). K. oxytoca endocarditis is extremely rare. The five reported cases are summarized in Table 1 (2–6). Of those cases, two were community acquired, as was this case (4). Fortunately, K. oxytoca endocarditis appears to have favorable outcomes, as reported cases show resolution with antibiotics alone (2, 4, 6). In contrast, K. pneumoniae endocarditis has a 49% mortality rate, and 44% of patients ultimately require valve replacement (1). K. oxytoca is an opportunistic gram-negative rod that is differentiated from K. pneumoniae by its indole positivity.

Table 1.

Previously reported cases of infective endocarditis caused by Klebsiella oxytoca

| Case (ref) | Age/sex | Presentation | Mode of entry | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Watanakunakorn, 1985 (2) | 87 M | UTI, bacteremia, IE | After transurethral resection of the prostate | Cefazolin, tobramycin |

| Repiso et al, 2001 (3) | 33 M | Bacteremia, IE (BP PV) | Intravenous drug user | Cefotaxime, gentamicin |

| Chen et al, 2006 (4) | 71 F | Bacteremia, IE (MV) | Community acquired, unknown mode of entry | Cefazolin |

| de Escalante et al, 2007 (5) | 75 M | Bacteremia, IE (AV) | Following AAA repair | Imipenem, gentamicin |

| Duggal et al, 2012 (6) | 66 M | Bacteremia, IE (BP AV) | Community acquired, unknown mode of entry | Ceftriaxone, gentamicin |

AAA indicates abdominal aortic aneurysm; AV, aortic valve; BP, bioprosthetic; IE, infective endocarditis; MV, mitral valve; PV, pulmonary valve; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Intravenous drug use is a significant risk factor for the development of infective endocarditis and a probable mode of entry in this patient, who had a history of injecting tap water-diluted intravenous drugs (8). Over 90% of infectious endocarditis cases in intravenous drug users are caused by gram-positive cocci, specifically staphylococci or streptococci, but other organisms are possible (9). In addition, neoplasia is a predisposing factor for developing K. oxytoca bacteremia (10). It is possible that this patient had prior metastatic spread of his seminoma to a retroperitoneal lymph node. He then seeded his blood with K. oxytoca through the injection of amphetamines diluted in tap water, where the bacteria then simultaneously colonized the necrotic lymph node and mitral valve, colonized the mitral valve with subsequent septic embolization to the lymph node, or colonized the necrotic lymph node with subsequent colonization of the mitral valve. Documented modes of entry for K. oxytoca in cases of bacteremia include, in descending order, the hepatobiliary tract (50%–55%), intravascular or urinary catheters (7%–16%), the urinary tract (5%–6%), skin and soft tissues (3%–5%), and the peritoneal cavity (2%–6%), while 23% to 34% of infections have no identifiable ports of entry (10, 11). Therefore, defining the precise route of entry in this patient is difficult, but intravenous drug use is strongly supported as the causal mechanism.

References

- 1.Anderson MJ, Janoff EN. Klebsiella endocarditis: report of two cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26(2):468–474. doi: 10.1086/516330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watanakunakorn C. Klebsiella oxytoca endocarditis after transurethral resection of the prostate gland. South Med J. 1985;78(3):356–357. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198503000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Repiso M, Castiello J, Repáraz J, Uriz J, Sola J, Elizondo MJ. Endocarditis caused by Klebsiella oxytoca a case report. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2001;19(9):454–455. doi: 10.1016/s0213-005x(01)72697-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen JY, Chen PS, Chen YP, Lee WT, Lin LJ. Community-acquired Klebsiella oxytoca endocarditis: a case report. J Infect. 2006;52(5):e129–e131. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Escalante Yangüela B, Aibar Arregui MA, Muñoz Villalengua M, Olivera González S. Klebsiella oxytoca nosocomial endocarditis. Med Interna. 2007;24(11):563–564. doi: 10.4321/s0212-71992007001100014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duggal A, Waraich KK, Cutrona A. Klebsiella oxytoca endocarditis in a patient with a bioprosthetic aortic valve. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2012;20(3):224–225. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoen B, Duval X. Clinical practice. Infective endocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(15):1425–1433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1206782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tung MK, Light M, Giri R, Lane S, Appelbe A, Harvey C, Athan E. Evolving epidemiology of injecting drug use-associated infective endocarditis: a regional centre experience. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2015;34(4):412–417. doi: 10.1111/dar.12228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathew J, Addai T, Anand A, Morrobel A, Maheshwari P, Freels S. Clinical features, site of involvement, bacteriologic findings, and outcome of infective endocarditis in intravenous drug users. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(15):1641–1648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin RD, Hsueh PR, Chang SC, Chen YC, Hsieh WC, Luh KT. Bacteremia due to Klebsiella oxytoca clinical features of patients and antimicrobial susceptibilities of the isolates. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24(6):1217–1222. doi: 10.1086/513637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim BN, Ryu J, Kim YS, Woo JH. Retrospective analysis of clinical and microbiological aspects of Klebsiella oxytoca bacteremia over a 10-year period. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2002;21(6):419–426. doi: 10.1007/s10096-002-0738-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]