Abstract

During chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, mutations in the precore (PC) or basal core promoter (BCP) region affecting HBV e antigen (HBeAg) expression occur commonly and represent the predominant virus species in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. The PC mutation (G1896A+C1858T) creates a translational stop codon resulting in absent HBeAg expression, whereas BCP mutations (A1762T/G1764A) reduce HBeAg expression by transcriptional mechanisms. Treatment of chronic HBV infection with lamivudine (LMV) often selects drug-resistant strains with single (rtM204I) or double (rtL180M+rtM204V) point mutations in the YMDD motif of HBV reverse transcriptase. We cloned replication-competent HBV vectors (genotype A, adw2) combining mutations in the core (wild type [wt], PC, and BCP) and polymerase gene (wt, rtM204I, and rtL180M/M204V) and analyzed virus replication and drug sensitivity in vitro. Resistance to LMV (rtM204I/rtL180M+rtM204V) was accompanied by a reduced replication efficacy as evidenced by reduced pregenomic RNA, encapsidated progeny DNA, polymerase activity, and virion release. PC mutations alone did not alter virus replication but restored replication efficacy of the LMV-resistant mutants without affecting drug resistance. BCP mutants had higher replication capacities than did the wt, also in combination with LMV resistance mutations. All nine HBV constructs showed similar sensitivities to adefovir. In conclusion, BCP-PC mutations directly impact the replication capacity of LMV-resistant mutants. PC mutations compensated for replication inefficiency of LMV-resistant mutants, whereas BCP mutations increased viral replication levels to above the wt baseline values, even in LMV-resistant mutants, without affecting drug sensitivity in vitro. Adefovir may be an effective treatment when combinations of core and polymerase mutations occur.

Persistent infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) represents a major health problem worldwide, with more than 350 million chronically infected patients at risk of developing liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (34). The viral genome contains four overlapping open reading frames: S, for the surface or envelope gene; C, for the core gene; X, for the regulatory X gene; and P, for the polymerase gene. The HBV core gene is divided into the precore (PC) region (29 amino acid codons) and the core region (181 codons) by two in-frame initiating ATG codons. This results in the transcription of either the pregenomic RNA that is essential for HBV replication and also translates into the nucleocapsid protein or the PC RNA that translates into HBV e antigen (HBeAg) protein. HBeAg is released into the bloodstream of infected patients, but it is not required for HBV replication in vitro (57).

It has been proposed that HBeAg may serve as a decoy to buffer anti-core protein immune response or to induce immune tolerance in perinatally infected individuals. On the other hand, the anti-HBe immune response results in an efficient reduction of viral load and thereby provides a strong selection pressure toward viral variants with less HBeAg expression or none (38, 48). During chronic HBV infection, two major types of HBV core gene variants frequently occur that affect the expression of HBeAg: the PC mutants and the basal core promoter (BCP) mutants (38).

The most prevalent PC mutation is a guanine-to-adenine transition at nucleotide position 1896 (G1896A), which creates a TAG stop codon at codon 28 of the PC protein and abolishes HBeAg expression at the translational level (38). However, this mutation is located within the epsilon (ɛ) structure, a highly conserved stem-loop essential for initiation of encapsidation within the viral replication cycle. In order to stabilize this ɛ structure, the nucleotide at position 1896 is paired with the nucleotide at position 1858, which naturally is a thymidine (T) in genotypes B, D, E, and G and a cytidine (C) in genotype A. Therefore, in HBV genotype A, the G1896A mutation usually arises together with a C1858T nucleotide exchange (39, 51). HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B related to PC and/or BCP mutations has become the predominant clinical presentation in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic HBV infection in many parts of the world (18, 23).

The most common BCP mutation is the double A1762T and G1764A nucleotide exchange, which results in a decrease of HBeAg expression of up to 70% but enhanced viral genome replication (6, 26, 38). The reduction of HBeAg expression is apparently mediated by reduced PC RNA transcription, while the mechanism of enhanced replication may involve altered transcription factor binding to the promoter, mutation in the overlapping HBx protein, and changes in the ratio of PC to pregenomic RNA (6, 33, 36, 38, 48). Moreover, carriers infected with HBV with the BCP mutations may be at increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (34).

Recent studies emphasize the high prevalence of PC and BCP mutants as the predominant viral species in chronic HBV infection (12), but treatment of these variants is challenging. At present, treatment options include the use of alpha interferon and nucleoside analogues such as lamivudine (LMV) or adefovir (ADV). Especially in PC mutants, the response rate for interferon is low, even with a longer duration of therapy than that for wild-type (wt) strains or retreatment strategies (15, 21, 41). LMV and ADV are regarded as safe and efficacious, but they usually require a treatment period over several years.

The major clinical limitation of LMV is the rapid selection of drug-resistant mutants. This is typically dependent on the duration of therapy, affecting up to 66% of patients after 3 years (35). LMV resistance develops at similar rates in HBeAg-positive and -negative patients (20, 40, 56) and has been associated with disease progression (25, 31). The most common mutations conferring LMV resistance affect the YMDD (tyrosine-methionine-aspartate-aspartate) motif, which is the active site in the HBV polymerase protein, where the methionine (M) residue at amino acid 204 is replaced by isoleucine (rtM204I) or valine (rtM204V). The rtM204V mutation is usually accompanied by a leucine (L)-to-methionine (M) change at position 180 (rtL180M) (14, 38, 44, 54).

The aim of our study was to analyze the impact of the different mutations in the PC, BCP, and polymerase region (single and in combination) on viral replication efficacy as well as drug sensitivity. By cloning the PC (G1896A/C1858T), BCP (A1762T/G1764A), and wt core sequences in combination with the major LMV resistance rtM204I and rtL180M/rtM204V mutations or wt polymerase sequences into replication-competent genotype A HBV vectors and performing in vitro studies, we were able to show that both PC and BCP mutations enhance the replication yield of LMV-resistant HBV mutants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning of replication-competent HBV vectors.

Specific mutations were introduced into the HBV genome (genotype A, subtype adw2). As the circular viral 3.2-kb HBV DNA generates a 3.5-kb RNA intermediate, replication-competent plasmid vectors need to carry at least 1.28-fold HBV genome. We therefore first cloned single genome constructs (“1.0”) combining the different mutations and then inserted these into wt or mutated “0.28” vectors to achieve replication-competent vectors with the 1.28-fold HBV genome (Fig. 1). In order to generate an HBV 1.0 wt construct, an RsrII linker sequence was introduced into the multiple cloning site of pBluescript SK(+) (pBS) (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) with the synthetic oligonucleotides RsrIIsense (5′ GGA ATT CGG ACC GAA TTCG 3′) and RsrIIanti (5′ CGA ATT CGG TCC GAA TTC C 3′). The single HBV genome (“HBV 1.0”) from the replication-competent HBV 1.28 constructs wt, rtM204I, and rtL180M/rtM204V (5) was excised using RsrII and cloned into RsrII-Bluescript.

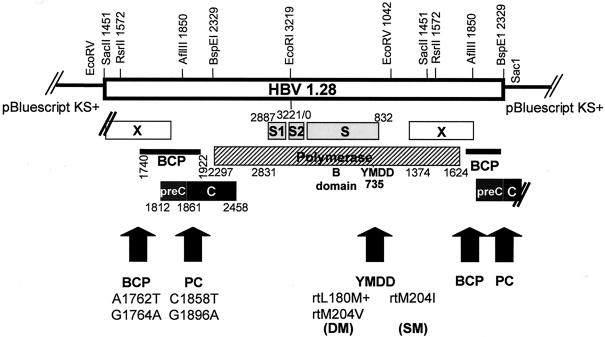

FIG. 1.

Schematic illustration of the replication-competent 1.28-fold-HBV vectors with restriction enzyme digestion sites. In the polymerase gene (striped), either wt or LMV resistance mutations (rtM204I or rtL180M+rtM204V) were present. In the BCP and the PC region (shaded), either wt sequences or the BCP (A1762T plus G1764A) or the PC (C1858T plus G1896A) mutation was introduced.

In order to introduce the BCP mutations A1762T and G1764A, site-directed mutagenesis (QuickChange; Stratagene) was performed using the mutagenesis primer 1762/64sense (5′ GAG GAG ATT AGG TTA ATG ATC TTT GTA TTA GGA GGC 3′) and 1762/64anti (5′ GCC TCC TAA TAC AAA GAT CAT TAA CCT AAT CTC CTC 3′) and HBV 1.0 wt plasmid as a template. The combination of the BCP with the LMV-resistant mutants was achieved by excising and exchanging the XhoI-BspEI fragment (796 bp).

In order to introduce the PC mutations G1896A and C1858T, the NspI fragment (2,437 bp) was excised from the HBV 1.0 wt and used as a template for PCR with the mutagenesis primer 1858Stop-sense (5′ GTA CAT GTC CTA CTG TTC AAG CCT CCA AGC TGT GCC TTG GGT GGC TTT AGG GCA TGG 3′) and the primer BspEIanti (5′ GTA GTT TCC GGA AGT GTT GA 3′). The PCR product containing the PC mutations was introduced into a TOPO-TA cloning vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) and digested with AflIII and BspEI (479 bp). HBV 1.0 wt was digested with XhoI and BspEI (796 bp) and cloned into the pACYC177 vector (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). The AflIII-BspEI fragment was then exchanged between the wt and the mutated TOPO-TA vector. The XhoI-BspEI fragment containing the PC mutations was again cloned into the HBV 1.0 Bluescript vectors with wt and LMV resistance mutations as described above.

All constructs were sequenced at each step of the cloning process with the primer preCanti (5′ CTA AGG CTT CTC GAT ACA GAG 3′) for the core and the primer 1800 (5′ GCT GGA TGT GTC TGC GGC 3′) for the polymerase region according to the protocol of the manufacturer (ABI Prism 310; Applied Biosystems Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.). All PCR amplifications were carried out using proofreading HotStart Herculase polymerase (Stratagene).

For replication competency, the HBV genome must have at least a 1.28-fold length of its sequence. We therefore constructed “0.28-fold” constructs with the different mutations in the core region (wt-BCP-PC). First, the 0.28 wt (878 bp) was constructed using the primers SacI-HBVrev (5′ ATG AGC TCT CCG GAA GTG TTG ATA AGA TAG G 3′) and ClaI-HBVfwd (5′ ATC CAT CGA TCC GCG GAC GAC CCC TCT CG 3′) and a 2.0 wt plasmid (3) as a template and cloned into pBluescript after an SacI-ClaI digest. The BCP and PC mutations were exchanged with the wt construct by RsrII-BspEI digestion and ligation. The different 0.28-backbone Bluescript plasmids were then linearized with RsrII, and the RsrII-RsrII-single HBV genome (1.0) from the different constructs was inserted to get 1.28 replication-competent vectors (Fig. 1). Again, all clones were full-length sequenced and controlled by restriction enzyme digestion.

Cell culture and transfection experiments.

Huh7 human hepatoma cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium as described before (5). Cells were transiently transfected by the calcium phosphate DNA precipitation method and harvested after 4 days. The amount of transfected viral DNA was kept constant in all experiments to 5 μg/6-cm-diameter dish. When increasing amounts of wt HBV were transfected (0, 1, 3, and 5 μg), the HBV DNA was complemented with pBluescript vector (5, 4, 2, and 0 μg, respectively) in order to transfect a total amount of 5 μg of DNA. Transfection efficiency was controlled by cotransfection of 0.5 μg of pCMV β-galactosidase (β-Gal) vector and measurement of β-Gal activity from cell lysates as described previously (5). Cell lysates from three 6-cm-diameter dishes were pooled for further analysis and treated as one experiment. All experiments were performed three times. For drug sensitivity testing, medium with different concentrations of LMV (3-TC; SmithKline Beecham, King of Prussia, Pa.) or ADV (PMEA; Moravek Biochemicals, Brea, Calif.) was used as indicated. Medium containing drugs was changed every other day (13).

RNA preparation, Northern blot analysis, and multiplex RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from Huh7 cells 4 days after transfection with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol (55). Northern blot analysis was performed as described previously, according to standard procedures (4). The 2.5-kb fragment after EcoRV and RsrII codigestion of HBV 1.28 plasmid was α-32P-radiolabeled and used as a monomeric HBV probe for hybridization detecting all HBV mRNAs. A second probe directed against β-Gal RNA was generated by EcoRI and HindIII codigestion of the pCMV-β-Gal reporter construct. Northern blot analysis was confirmed by multiplex reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) with primer pairs for the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), S, and C genes in one reaction essentially as described previously (30), except for the GAPDH primers for the human GAPDH gene (sense, 5′ GAC AGT CAG CCG CAT CTT CTT TTG 3′; antisense, 5′ TGC TGA TGA TCT TGA GGC TGT TGT 3′).

Isolation of encapsidated HBV DNA by immunoprecipitation and detection of HBV progeny DNA by dot blot assay.

Progeny HBV DNA was isolated from transfected cells as previously described (3). In brief, cells were harvested 4 days after transfection and lysed with a buffer containing 1% NP-40. Total protein content of the cell lysate was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Munich, Germany). Intracellular HBV capsids were immunoprecipitated using an anti-HBc antibody (Dako, Hamburg, Germany) and protein A agarose (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Contaminating plasmid HBV DNA was eliminated by DNase and RNase digestion (Roche). HBV capsids were digested by proteinase K (500 μg/ml, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]), and HBV progeny DNA was extracted by the phenol chloroform procedure and precipitated with ethanol. Progeny DNA was then detected using an α-32P-radiolabeled HBV DNA probe and the dot blot analysis method (5). Data were quantified using the NIH Imager system and normalized to the applied total protein content.

Endogenous HBV DNA polymerase activity.

The intracellular HBV DNA polymerase activity was measured by the endogenous polymerase assay as described before (30). Briefly, intracellular HBV capsids were isolated by immunoprecipitation as described for the progeny DNA analysis and, after DNase-RNase digestion, incubated in a buffer containing 10 μCi of [α-32P]dCTP and unlabeled dGTP, dATP, and dTTP (100 μM each). Newly synthesized HBV DNA was isolated after proteinase K-SDS digestion followed by phenol chloroform extraction, run on a 1% agarose gel, and visualized by exposure to an X-ray film.

Detection of mature HBV virions and quantification of HBV DNA from supernatant.

HBV viral particles from the cell culture supernatant were precipitated using polyethylene glycol (PEG; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) followed by DNase and RNase digestion (Roche Diagnostics), proteinase K digestion (500 μg/ml, 1% SDS), phenol chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation of mature HBV DNA, as previously described (5). A quantitative real-time PCR was applied to quantify HBV DNA according to a protocol described by Jursch et al. (28) Briefly, a 189-bp fragment of the X region was amplified in a LightCycler system (Roche Diagnostics) with a standard FastStart polymerase kit and buffers (Roche Diagnostics) and the following probes and primers: 3FL-XHybprobe, 5′-ACG GGG CGC ACC TCT CTT TAC GCG G fluorescein-3′; 5LC-Xhybprobe, 5′-(LCRed 640-nm)CTC CCC GTC TGT GCC TTC TCA TCT GC PH-3′; X sense, 5′-GAC GTC CTT TGT YTA CGT CCC GTC-3′; X antisense, 5′-TGC AGA GGT GAA GCG AAG TGC ACA-3′. The LightCycler program consisted of an initial denaturation and activation of the FastStart polymerase (95°C; 10 min; slope, 20°C/s), 45 cycles of amplification with touchdown (95°C for 10 s, 62 to 50°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 13 s; slope of 5°C/s), melting curve (cooling from 95 to 50°C for 10 s with a slope of 20°C/s and heating again to 95°C for 0 s with a slope of 0.1°C/s), and cooling (40°C for 30 s with a slope of 20°C/s). Standard dilutions of linearized HBV 1.0 wt plasmid were used to generate a standard curve, and serum samples from patients with acute hepatitis B served as positive controls. All measurements were carried out in triplicate.

Detection of HBsAg and HBeAg in supernatant.

HBsAg and HBeAg were measured in the supernatant by commercial assays (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, Ill.) (3).

Statistics.

Results are reported as means ± standard deviations. The t test was applied for comparisons between the groups; a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill.).

RESULTS

Cloning of the HBV replication-competent constructs.

In order to test the effect of the commonly selected PC and BCP mutations on HBV replication and drug resistance, either the wt sequence or the C1858T/G1896A (PC) or A1762T/G1764A (BCP) mutations were introduced into the HBV genome and combined with either the wt polymerase sequence or the LMV-resistant mutants with the single rtM204I mutation (SM) or the double rtL180M/rt204V mutation (DM). Replication-competent plasmid vectors with the 1.28-fold HBV genome were generated (Fig. 1), and sequences of all clones were checked for the correct occurrence of mutations in the BCP and PC region as well as in the polymerase domains. The constructs were tested by transient transfection in the human hepatoma cell line Huh7. Genotype A, subtype adw2, was chosen because this is the most common HBV genotype in western Europe. Furthermore, PC and especially BCP mutations are common in this genotype (38). Each panel of constructs was tested in at least three independent experiments, and similar results were obtained. Transfection efficiency was controlled in all experiments by cotransfection of pCMV-β-Gal plasmid and measurement of β-Gal activity.

Influence of HBV mutations on intracellular replication efficacy.

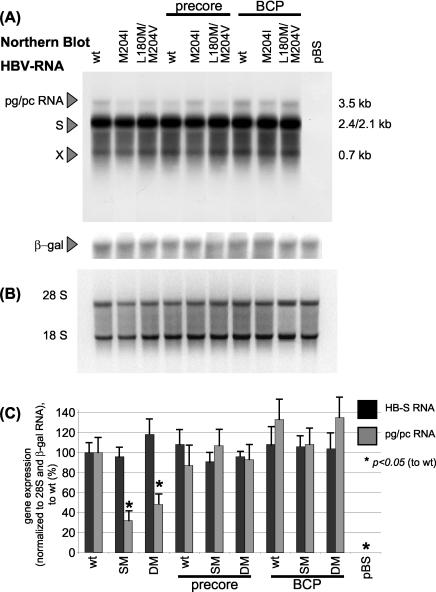

Transcriptional activity of the different HBV mutants was analyzed by Northern blotting. The amounts of detected HBV-S- and pregenomic-PC RNA (Fig. 2A) were normalized to β-Gal RNA (for transfection efficiency control) and the amount of applied total RNA as detected by the 18S-28S band (Fig. 2B). The strength of the signals was quantified using the NIH Imager system and was normalized to HBV wt construct (Fig. 2C). While the amounts of specific HBV-S mRNA expression did not display major differences, pregenomic-PC RNA levels were significantly reduced in the LMV-resistant strains rtM204I and rtL180M+rtM204V. However, combination of these mutations with the PC resulted in an increase of pregenomic RNA to wt level. The combination with BCP mutations further increased pregenomic-PC RNA levels; however, this difference did not reach statistical significance.

FIG. 2.

(A) Representative Northern blot analysis of HBV-specific RNA, 4 days after transient transfection with HBV wt or mutant constructs. Fifteen micrograms of total cellular RNA was loaded per lane. The Northern blot was also incubated with a probe directed against β-Gal RNA in order to control transfection efficiency. (B) 28S and 18S RNA of the same Northern blot. (C) Quantification of HBV-S RNA and pregenomic-PC RNA normalized to β-Gal RNA and 28S. Means and standard deviations are based on three independent experiments; values are given relative to wt. Significant differences compared with wt expression are indicated by an asterisk. (D) Representative semiquantitative triplex RT-PCR with primer pairs detecting the HBV-S gene (and the overlapping polymerase gene), the HBV-C region (of the pregenomic-pC RNA), and GAPDH as a cellular housekeeping gene. Results after 18 cycles are shown where the PCR was calculated to be within the linear mode of amplification. (E) Quantification of the S product and the C product relative to GAPDH expression. Means and standard deviations are based on more than three independent experiments; values are given relative to wt. Significant differences compared with wt expression are indicated by an asterisk. SM, single mutant (rtM204I); DM, double mutant (rtL180M/rtM204V); pBS, pBluescript plasmid; pg/pc RNA, pregenomic-PC RNA (3.5-kb band).

We also applied a semiquantitative triplex RT-PCR, in which primer pairs covering the HBV-S and HBV-C gene were used for amplification. GAPDH as a cellular housekeeping gene was included as an internal control (Fig. 2D). As the S gene overlaps with the polymerase (Fig. 1), the S primers also detected pregenomic RNA. Quantification of the PCR products in the calculated linear area of amplification showed significantly decreased C products in the LMV-resistant mutants alone, whereas the LMV-resistant-PC combination mutants and all the BCP constructs displayed levels similar to, or, for the BCP-SM/DM constructs, higher than, the wt (Fig. 2E). In accordance with the Northern blot analysis, this also indicates that the pregenomic-PC RNA levels are reduced in LMV-resistant mutants alone, while the combination with the PC or BCP mutations is able to enhance transcription of pregenomic-PC RNA (3.5-kb band) to wt level. In BCP mutants, a tendency toward an enhanced transcription of pregenomic RNA above the wt level was noticed.

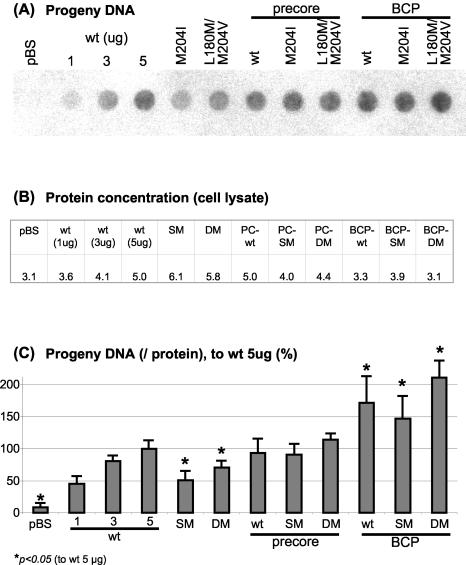

The intracellular replication capacity of the mutants was tested by isolating the encapsidated HBV progeny DNA (Fig. 3A). Briefly, intracellular HBV nucleocapsids were harvested from cell lysates 4 days after transfection by immunoprecipitation, and encapsidated progeny DNA was isolated and blotted on a membrane by the dot blot procedure. Progeny DNA intensity in the dot blot analysis was standardized to the total protein content of the applied cell lysates (Fig. 3B) and was quantified accordingly (Fig. 3C). When increasing amounts of wt HBV were transfected, a nearly linear increase in progeny DNA was detected (wt, 1 to 3 to 5 μg). In contrast, transfection with 5 μg of rtM204I or rtL180M+rtM204V resulted in a significant reduction of progeny DNA levels, confirming previous observations (5, 9, 43, 45, 46). Introduction of the PC mutations into a wt background had no effect on replication, but the combination of the PC mutations with the LMV resistance mutations restored the yield to wt replication levels. Moreover, the BCP constructs with either the wt or LMV resistance polymerase sequences had a significantly enhanced replication efficacy compared to the wt HBV construct.

FIG. 3.

(A) Progeny DNA with dot blot analysis after immunoprecipitation of intracellular HBV capsids, 4 days after transient transfection with HBV wt or mutant constructs. For wt HBV, increasing amounts of transfected DNA (1, 3, and 5 μg) are shown; all other constructs were transfected with 5 μg. This experiment has been performed more than three times with consistent results; one representative dot blot analysis is shown. (B) Protein concentration of the cell lysates used for progeny DNA analysis as measured by Bio-Rad protein assay. (C) Quantification of HBV progeny DNA (per protein concentration of cell lysates). Means and standard deviations are based on more than three independent experiments; values are given relative to wt. Significant differences compared with wt expression are indicated by an asterisk.

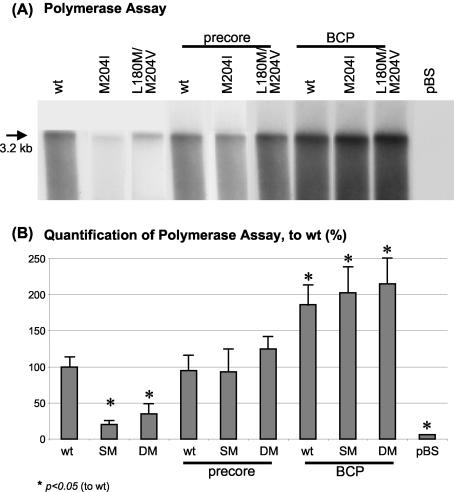

Similarly, endogenous HBV polymerase activity was measured. After immunoprecipitation of intracellular HBV capsids, the nucleocapsids were incubated with radioactively labeled nucleotides. After the incubation time, the capsids were lysed, and the intracapsid newly synthesized HBV DNA was run on a gel and visualized on an X-ray film. This typically resulted in a band of (double-stranded) 3.2-kb HBV DNA followed by a smear of smaller fragments of newly synthesized DNA (5). The 3.2-kb band was used for quantification. The polymerase activity was found to be significantly reduced in LMV-resistant mutants alone compared with wt constructs (Fig. 4). Again, the PC mutations alone and in combination with LMV resistance had activity similar to that of the wt, while all the BCP mutants had an enhanced polymerase activity.

FIG. 4.

(A) Endogenous HBV DNA polymerase assay visualizing polymerase activity of intracellular encapsidated HBV, 4 days after transient transfection with 5 μg of HBV wt or mutant constructs. One representative experiment is shown. (B) Quantification of the HBV polymerase activity. Means and standard deviations are based on three independent experiments; values are given relative to wt. Significant differences compared with wt expression are indicated by an asterisk.

Influence of HBV mutations on extracellular HBV virion and HBsAg and HBeAg secretion.

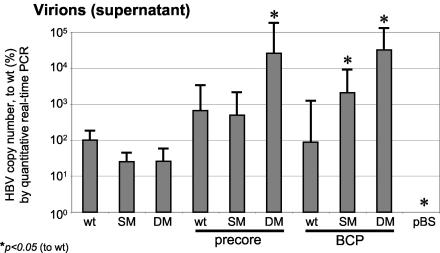

Newly synthesized HBV virions released into supernatant were PEG precipitated 4 days after transfection and measured using a quantitative real-time PCR approach (28). Linearized HBV 1.0 wt plasmid was serially diluted as a standard, and a reliable standard curve was obtained by which reference serum from patients with acute HBV infection could be accurately quantified (data not shown). In line with the intracellular replication efficacies, LMV-resistant mutants displayed decreased levels of released HBV virions in the supernatant 4 days after transfection (Fig. 5). In contrast, PC and BCP mutations with either a wt or LMV resistance genetic background had HBV virion numbers similar to or higher than those of the wt HBV construct. Especially in PC-rtL180M/rtM204V and in BCP-rtM204I or BCP-rtL180M/rtM204V mutants, we observed increased accumulation of HBV virions in the supernatant. Due to the accumulation of newly secreted virions in the supernatant over 4 days, the differences for the highly replicating strains appear pronounced.

FIG. 5.

Quantification of HBV copy number from supernatant by quantitative real-time PCR, 4 days after transient transfection with HBV wt or mutant constructs and after PEG precipitation of secreted virions. Mean values and standard deviations from three independent experiments are shown. Values are normalized to HBV copy number of the wt construct (100%). Significant differences compared with wt expression are indicated by an asterisk.

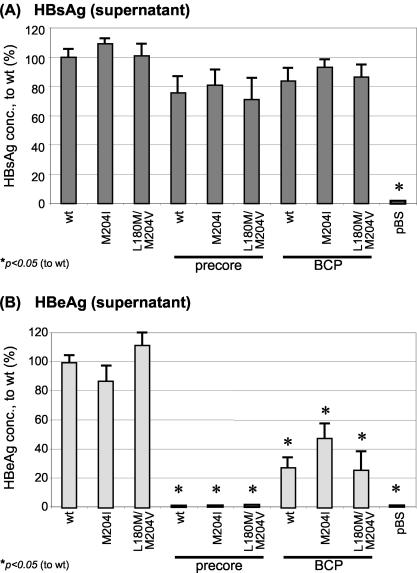

HBsAg concentrations in the supernatant did not differ significantly between the HBV mutants and wt (Fig. 6A). Not surprisingly, PC mutants were unable to secrete HBeAg into the supernatant, whereas HBeAg levels were decreased between 50 and 70% in the BCP mutants (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Mean HBsAg (A) or HBeAg (B) concentrations (from six independent experiments) measured in the supernatant, 4 days after transient transfection with HBV wt or mutant constructs. Values are normalized to the HBsAg (A) or HBeAg (B) level of wt. Significant differences compared with wt expression are indicated by an asterisk.

Sensitivity of wt HBV and mutants to LMV or ADV.

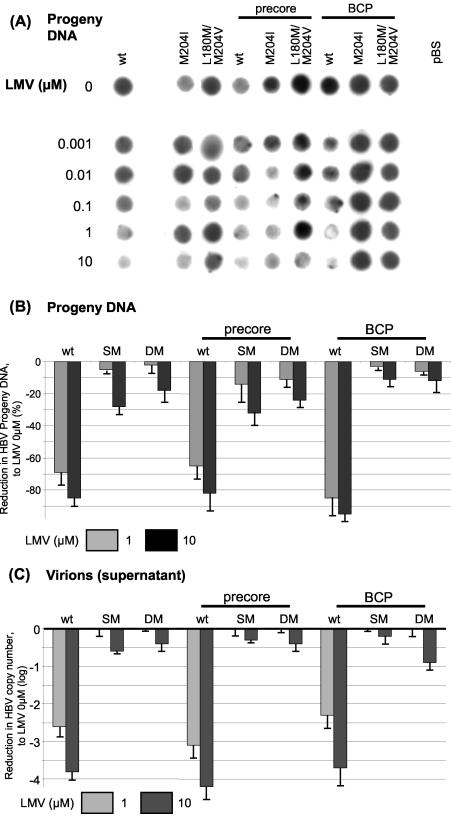

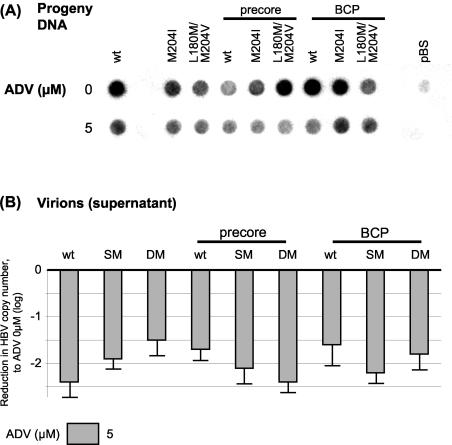

In order to test the sensitivities of the different HBV constructs to the clinically approved antiviral nucleotide or nucleoside analogue LMV or ADV, cells were transfected as described above and kept in medium containing different concentrations of the drugs for 4 days. After harvesting and extraction of intracellular HBV capsids, progeny DNA was quantified by dot blot analysis to monitor intracellular replication (Fig. 7A and B). Secreted HBV virions from supernatant were PEG precipitated and measured by quantitative real-time PCR to assess extracellular HBV virion release (Fig. 7C). Introduction of either PC or BCP mutations into the wt background did not markedly affect drug sensitivity to LMV. On the other hand, LMV-resistant mutants exhibited drug resistance to LMV, and this was also evident when combined with PC or BCP mutations. All constructs were sensitive to treatment with ADV, and no major differences in drug sensitivities to ADV across the panel of mutants were noticed (Fig. 8).

FIG. 7.

(A) Drug sensitivity testing for LMV. Progeny DNA with dot blot analysis after immunoprecipitation of intracellular HBV capsids, 4 days after transient transfection with HBV wt or mutant constructs. Medium contained different LMV concentrations as indicated in the figure. One representative experiment is shown. (B) Quantification of HBV progeny DNA (per protein concentration of cell lysates) after incubation with 1 and 10 μM LMV. Means and standard deviations are based on three independent experiments; values are given relative to incubation without LMV. Differences between the wt-SM/PC-SM/BCP-SM or wt-DM/PC-DM/BCP-DM constructs did not reach statistical significance. (C) Quantification of HBV copy number from supernatant 4 days after transient transfection with HBV wt or mutant constructs and after PEG precipitation of secreted virions. Log fold reduction in HBV copy number due to 1 or 10 μM LMV condition compared with no treatment is shown, as are means and standard deviations based on three independent experiments.

FIG. 8.

(A) Drug sensitivity testing for ADV. The figure shows progeny DNA with dot blot analysis after immunoprecipitation of intracellular HBV capsids, 4 days after transient transfection with HBV wt or mutant constructs. Medium contained either 0 or 5 μM ADV. One representative experiment is shown. (B) Quantification of HBV copy number from supernatant, 4 days after transient transfection with HBV wt or mutant constructs and after PEG precipitation of secreted virions. Log fold reduction in HBV copy number in 5 μM ADV condition compared with no treatment is shown, as are means and standard deviations based on three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study we aimed to determine the impact of the common PC and BCP mutations on viral replication efficiency as well as antiviral drug sensitivity in HBV constructs with either wt or LMV-resistant polymerase enzymes. We successfully cloned the C1858T/G1896A (PC) and the A1762T/G1764A (BCP) mutations into replication-competent HBV vectors with the wt polymerase sequence or with the LMV resistance mutation rt204I (SM) or rt180M/rtM204V (DM) and tested the constructs in vitro by transient transfection of human hepatoma cells.

The constructs with the LMV resistance mutations alone displayed drug resistance against LMV but had decreased replication capacity as evidenced by reduced pregenomic-PC RNA level and reduced encapsidated progeny DNA and polymerase activity as well as lower levels of secreted HBV virions. This is generally in accordance with previous studies of LMV-resistant mutants in vitro (5, 9, 43, 45, 46). In addition, our study suggests that a decrease in pregenomic RNA transcription may contribute in part to this reduced replication capacity of LMV-resistant mutants, as this has not been analyzed in previous studies (9, 44, 45). Notably, the double point rtL180M/rtM204V mutants replicated slightly better than the single rtM204I mutants, although not statistically significantly. This has been attributed to the potential stabilizing effect of the rtL180M mutation (B domain) on the YMDD loop (C domain) in a conformational model of the HBV reverse transcriptase (44).

For the PC mutants, we showed that introduction of the PC mutations into the wt background did not affect replication yield or drug sensitivity to LMV, but the combination of the PC mutations with the LMV resistance mutations restored the wt replication competence in the drug-resistant mutants. Recently, Chen et al. introduced the single G1896A mutation into a replication-competent baculovirus system based on the HBV genotype D, subtype ayw, and also reported that the G1896A PC stop codon increased replication yields of LMV-resistant virus (9). Our data indicate that this is a general mechanism independent of the HBV genotype, as we used the HBV genotype A (adw2) in this study. Furthermore, our study allowed us to investigate the effects of both PC and BCP mutations on LMV-resistant mutants, by introducing these mutations in different constructs of the same genotype.

Several factors might be involved in enhancing the replication yield by combining the PC with LMV resistance mutations. First, the PC protein has been reported to inhibit HBV DNA synthesis, and point mutations which abolish proper PC protein expression enhance progeny DNA expression (19, 32, 52, 53). In fact, 3.5-kb pregenomic-PC RNA levels in Northern blots as well as progeny DNA levels were restored in PC-LMV-resistant mutants compared with wt. Second, the epsilon (ɛ) structure involved in viral packaging and initiation of reverse transcription is usually stabilized by the PC mutations. The ɛ structure is a 5′-end stem-loop of the viral pregenomic RNA where the HBV polymerase binds and which is essential for the encapsidation of the HBV pregenomic RNA by triggering assembly of core proteins (27, 50). The modified lower stem of the ɛ in PC mutants may increase packaging efficiency of the polymerase-pregenomic RNA complex, possibly due to steric modifications related to the A-T base pairing. In accordance, we observed a restored polymerase activity in the endogenous polymerase assay.

Furthermore, viral resistance to LMV appeared to be unaffected by the PC mutations, although the high degree of LMV resistance in our in vitro system may not allow us to study minor differences in drug sensitivity (10). However, a reversion from PC mutation to wt has been occasionally observed in patients being treated with LMV, suggesting a reduced drug sensitivity in PC-LMV-resistant mutants in vivo (40). In contrast, we did not see differences in drug resistance of PC-LMV-resistant combination mutants in vitro. Similar results have been obtained with the baculovirus system (9) as well as in a large prospective clinical study with HBeAg-negative patients (20, 47).

For the BCP mutants, we could demonstrate an increased viral replication level and reduced HBeAg expression compared with the wt construct, consistent with previous reports (6, 38, 48). Interestingly, this was also found for the combination of BCP with LMV-resistant mutants, which had a strong increase in intracellular HBV replication as well as HBV virion release compared with LMV-resistant mutants alone. The BCP hotspot mutations A1762T/G1764A may increase HBV replication via altered transcription factor binding to the promoter, mutation in the overlapping HBx protein, and changes in the ratio of PC to pregenomic RNA (6, 33, 36, 38, 48).

Possible correlations between occurrence of core promoter mutations and clinical course of HBV infection have been investigated intensively and led to partly conflicting results (8, 16, 24, 37, 58). However, several reports suggest an association between BCP mutations and hepatocarcinogenesis (2, 17, 29). The core promoter mutants are the predominant viral species at the late HBeAg-positive and the anti-HBe stage of infection and are preferentially found in genotype A-infected patients (7, 11, 38). Our study with genotype A constructs revealed that the BCP mutants had higher replication yields when directly compared with wt or PC mutants, thereby supporting this clinical observation from our molecular analysis. In addition, BCP mutants also carrying the LMV resistance mutations maintained the phenotype of drug resistance to LMV.

Interestingly, wt and PC and BCP mutants displayed comparable sensitivities to ADV, which has recently been approved as a treatment option in chronic HBV infection (22, 42). ADV was similarly active in wt and LMV-resistant mutants in vitro, confirming observations from clinical trials of patients with LMV-resistant mutants (15, 49). In addition, long-term treatment with ADV seems to have only a low risk for development of drug resistance mutations (1). Our in vitro data support the use of ADV therapy for LMV-resistant PC and BCP mutants.

Taken together, the presence of PC mutations was found to compensate for replication deficiency of LMV-resistant mutants, and the presence of BCP mutations increased viral replication above the wt baseline level even in LMV-resistant mutants. These observations may have major clinical implications, as chronically infected HBV patients undergoing LMV therapy should be closely monitored for HBV DNA levels, especially HBeAg-negative patients. In fact, LMV resistance has been associated with worsening of liver disease in HBeAg-negative chronic HBV infection (20, 23). Moreover, alternative drugs such as ADV or combination chemotherapy may be especially useful in HBeAg-negative patients, in order to minimize the risk for the selection of drug-resistant mutants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen A. Locarini from the Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory, North Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, who kindly provided the antiviral compounds.

This research was supported by Gilead Sciences, Martinsried, Germany. This work was supported by HepNet, the German network of competence for viral hepatitis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angus, P., R. Vaughan, S. Xiong, H. Yang, W. E. Delaney, C. Gibbs, C. L. Brosgart, D. Colledge, R. Edwards, A. Ayres, A. Bartholomeusz, and S. Locarnini. 2003. Resistance to adefovir dipivoxil therapy associated with the selection of a novel mutation in the HBV polymerase. Gastroenterology 125:292-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baptista, M., A. Kramvis, and M. C. Kew. 1999. High prevalence of 1762(T) 1764(A) mutations in the basic core promoter of hepatitis B virus isolated from black Africans with hepatocellular carcinoma compared with asymptomatic carriers. Hepatology 29:946-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bock, C. T., B. Buerke, H. L. Tillmann, F. Tacke, V. Kliem, M. P. Manns, and C. Trautwein. 2003. Relevance of hepatitis B core gene deletions in patients after kidney transplantation. Gastroenterology 124:1809-1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bock, C. T., H. L. Tillmann, H. J. Maschek, M. P. Manns, and C. Trautwein. 1997. A preS mutation isolated from a patient with chronic hepatitis B infection leads to virus retention and misassembly. Gastroenterology 113:1976-1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bock, C. T., H. L. Tillmann, J. Torresi, J. Klempnauer, S. Locarnini, M. P. Manns, and C. Trautwein. 2002. Selection of hepatitis B virus polymerase mutants with enhanced replication by lamivudine treatment after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology 122:264-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buckwold, V. E., Z. Xu, M. Chen, T. S. Yen, and J. H. Ou. 1996. Effects of a naturally occurring mutation in the hepatitis B virus basal core promoter on precore gene expression and viral replication. J. Virol. 70:5845-5851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan, H. L., M. Hussain, and A. S. Lok. 1999. Different hepatitis B virus genotypes are associated with different mutations in the core promoter and precore regions during hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion. Hepatology 29:976-984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan, H. L., S. W. Tsang, C. T. Liew, C. H. Tse, M. L. Wong, J. Y. Ching, N. W. Leung, J. S. Tam, and J. J. Sung. 2002. Viral genotype and hepatitis B virus DNA levels are correlated with histological liver damage in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 97:406-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, R. Y., R. Edwards, T. Shaw, D. Colledge, W. E. Delaney, H. Isom, S. Bowden, P. Desmond, and S. A. Locarnini. 2003. Effect of the G1896A precore mutation on drug sensitivity and replication yield of lamivudine-resistant HBV in vitro. Hepatology 37:27-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chin, R., T. Shaw, J. Torresi, V. Sozzi, C. Trautwein, T. Bock, M. Manns, H. Isom, P. Furman, and S. Locarnini. 2001. In vitro susceptibilities of wild-type or drug-resistant hepatitis B virus to (−)-β-d-2,6-diaminopurine dioxolane and 2′-fluoro-5-methyl-β-l-arabinofuranosyluracil. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2495-2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu, C. J., E. B. Keeffe, S. H. Han, R. P. Perrillo, A. D. Min, C. Soldevila-Pico, W. Carey, R. S. Brown, Jr., V. A. Luketic, N. Terrault, and A. S. Lok. 2003. Hepatitis B virus genotypes in the United States: results of a nationwide study. Gastroenterology 125:444-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu, C. J., E. B. Keeffe, S. H. Han, R. P. Perrillo, A. D. Min, C. Soldevila-Pico, W. Carey, R. S. Brown, Jr., V. A. Luketic, N. Terrault, and A. S. Lok. 2003. Prevalence of HBV precore/core promoter variants in the United States. Hepatology 38:619-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delaney, W. E., R. Edwards, D. Colledge, T. Shaw, J. Torresi, T. G. Miller, H. C. Isom, C. T. Bock, M. P. Manns, C. Trautwein, and S. Locarnini. 2001. Cross-resistance testing of antihepadnaviral compounds using novel recombinant baculoviruses which encode drug-resistant strains of hepatitis B virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1705-1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delaney, W. E., S. Locarnini, and T. Shaw. 2001. Resistance of hepatitis B virus to antiviral drugs: current aspects and directions for future investigation. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 12:1-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.EASL consensus statement. 2003. EASL International Consensus Conference on Hepatitis B, 13 to 14 September 2002, Geneva, Switzerland. Consensus statement (short version). J. Hepatol. 38:533-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erhardt, A., U. Reineke, D. Blondin, W. H. Gerlich, O. Adams, T. Heintges, C. Niederau, and D. Haussinger. 2000. Mutations of the core promoter and response to interferon treatment in chronic replicative hepatitis B. Hepatology 31:716-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang, Z. L., J. Yang, X. Ge, H. Zhuang, J. Gong, R. Li, R. Ling, and T. J. Harrison. 2002. Core promoter mutations (A(1762)T and G(1764)A) and viral genotype in chronic hepatitis B and hepatocellular carcinoma in Guangxi, China. J. Med. Virol. 68:33-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Funk, M. L., D. M. Rosenberg, and A. S. Lok. 2002. World-wide epidemiology of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B and associated precore and core promoter variants. J. Viral Hepat. 9:52-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guidotti, L. G., B. Matzke, C. Pasquinelli, J. M. Shoenberger, C. E. Rogler, and F. V. Chisari. 1996. The hepatitis B virus (HBV) precore protein inhibits HBV replication in transgenic mice. J. Virol. 70:7056-7061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadziyannis, S. J., G. V. Papatheodoridis, E. Dimou, A. Laras, and C. Papaioannou. 2000. Efficacy of long-term lamivudine monotherapy in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 32:847-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hadziyannis, S. J., G. V. Papatheodoridis, and D. Vassilopoulos. 2003. Treatment of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Semin. Liver Dis. 23:81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hadziyannis, S. J., N. C. Tassopoulos, E. J. Heathcote, T. T. Chang, G. Kitis, M. Rizzetto, P. Marcellin, S. G. Lim, Z. Goodman, M. S. Wulfsohn, S. Xiong, J. Fry, and C. L. Brosgart. 2003. Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:800-807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hadziyannis, S. J., and D. Vassilopoulos. 2001. Hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 34:617-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honda, A., O. Yokosuka, T. Ehata, M. Tagawa, F. Imazeki, and H. Saisho. 1999. Detection of mutations in the enhancer 2/core promoter region of hepatitis B virus in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: comparison with mutations in precore and core regions in relation to clinical status. J. Med. Virol. 57:337-344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Honkoop, P., H. G. Niesters, R. A. de Man, A. D. Osterhaus, and S. W. Schalm. 1997. Lamivudine resistance in immunocompetent chronic hepatitis B. Incidence and patterns. J. Hepatol. 26:1393-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunt, C. M., J. M. McGill, M. I. Allen, and L. D. Condreay. 2000. Clinical relevance of hepatitis B viral mutations. Hepatology 31:1037-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeong, J. K., G. S. Yoon, and W. S. Ryu. 2000. Evidence that the 5′-end cap structure is essential for encapsidation of hepatitis B virus pregenomic RNA. J. Virol. 74:5502-5508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jursch, C. A., W. H. Gerlich, D. Glebe, S. Schaefer, O. Marie, and O. Thraenhart. 2002. Molecular approaches to validate disinfectants against human hepatitis B virus. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. (Berlin) 190:189-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kao, J. H., P. J. Chen, M. Y. Lai, and D. S. Chen. 2003. Basal core promoter mutations of hepatitis B virus increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B carriers. Gastroenterology 124:327-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein, C., C. T. Bock, H. Wedemeyer, T. Wüstefeld, S. A. Locarnini, H. P. Dienes, S. Kubicka, M. P. Manns, and C. Trautwein. 2003. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication in vivo by nucleoside analogues and siRNA. Gastroenterology 125:9-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai, C. L., J. Dienstag, E. Schiff, N. W. Leung, M. Atkins, C. Hunt, N. Brown, M. Woessner, R. Boehme, and L. Condreay. 2003. Prevalence and clinical correlates of YMDD variants during lamivudine therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:687-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamberts, C., M. Nassal, I. Velhagen, H. Zentgraf, and C. H. Schroder. 1993. Precore-mediated inhibition of hepatitis B virus progeny DNA synthesis. J. Virol. 67:3756-3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laras, A., J. Koskinas, and S. J. Hadziyannis. 2002. In vivo suppression of precore mRNA synthesis is associated with mutations in the hepatitis B virus core promoter. Virology 295:86-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee, W. M. 1997. Hepatitis B virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:1733-1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leung, N. W., C. L. Lai, T. T. Chang, R. Guan, C. M. Lee, K. Y. Ng, S. G. Lim, P. C. Wu, J. C. Dent, S. Edmundson, L. D. Condreay, and R. N. Chien. 2001. Extended lamivudine treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B enhances hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion rates: results after 3 years of therapy. Hepatology 33:1527-1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li, J., V. E. Buckwold, M. W. Hon, and J. H. Ou. 1999. Mechanism of suppression of hepatitis B virus precore RNA transcription by a frequent double mutation. J. Virol. 73:1239-1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindh, M., C. Hannoun, A. P. Dhillon, G. Norkrans, and P. Horal. 1999. Core promoter mutations and genotypes in relation to viral replication and liver damage in East Asian hepatitis B virus carriers. J. Infect. Dis. 179:775-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Locarnini, S., J. McMillan, and A. Bartholomeusz. 2003. The hepatitis B virus and common mutants. Semin. Liver Dis. 23:5-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lok, A. S., U. Akarca, and S. Greene. 1994. Mutations in the pre-core region of hepatitis B virus serve to enhance the stability of the secondary structure of the pre-genome encapsidation signal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:4077-4081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lok, A. S., M. Hussain, C. Cursano, M. Margotti, A. Gramenzi, G. L. Grazi, E. Jovine, M. Benardi, and P. Andreone. 2000. Evolution of hepatitis B virus polymerase gene mutations in hepatitis B e antigen-negative patients receiving lamivudine therapy. Hepatology 32:1145-1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manesis, E. K., and S. J. Hadziyannis. 2001. Interferon alpha treatment and retreatment of hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 121:101-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marcellin, P., T. T. Chang, S. G. Lim, M. J. Tong, W. Sievert, M. L. Shiffman, L. Jeffers, Z. Goodman, M. S. Wulfsohn, S. Xiong, J. Fry, and C. L. Brosgart. 2003. Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:808-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melegari, M., P. P. Scaglioni, and J. R. Wands. 1998. Hepatitis B virus mutants associated with 3TC and famciclovir administration are replication defective. Hepatology 27:628-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ono, S. K., N. Kato, Y. Shiratori, J. Kato, T. Goto, R. F. Schinazi, F. J. Carrilho, and M. Omata. 2001. The polymerase L528M mutation cooperates with nucleotide binding-site mutations, increasing hepatitis B virus replication and drug resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 107:449-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ono-Nita, S. K., N. Kato, Y. Shiratori, K. H. Lan, H. Yoshida, F. J. Carrilho, and M. Omata. 1999. Susceptibility of lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus to other reverse transcriptase inhibitors. J. Clin. Investig. 103:1635-1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ono-Nita, S. K., N. Kato, Y. Shiratori, T. Masaki, K. H. Lan, F. J. Carrilho, and M. Omata. 1999. YMDD motif in hepatitis B virus DNA polymerase influences on replication and lamivudine resistance: a study by in vitro full-length viral DNA transfection. Hepatology 29:939-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Papatheodoridis, G. V., E. Dimou, A. Laras, V. Papadimitropoulos, and S. J. Hadziyannis. 2002. Course of virologic breakthroughs under long-term lamivudine in HBeAg-negative precore mutant HBV liver disease. Hepatology 36:219-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parekh, S., F. Zoulim, S. H. Ahn, A. Tsai, J. Li, S. Kawai, N. Khan, C. Trepo, J. Wands, and S. Tong. 2003. Genome replication, virion secretion, and e antigen expression of naturally occurring hepatitis B virus core promoter mutants. J. Virol. 77:6601-6612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perrillo, R., E. Schiff, E. Yoshida, A. Statler, K. Hirsch, T. Wright, K. Gutfreund, P. Lamy, and A. Murray. 2000. Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B mutants. Hepatology 32:129-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pollack, J. R., and D. Ganem. 1993. An RNA stem-loop structure directs hepatitis B virus genomic RNA encapsidation. J. Virol. 67:3254-3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodriguez-Frias, F., M. Buti, R. Jardi, M. Cotrina, L. Viladomiu, R. Esteban, and J. Guardia. 1995. Hepatitis B virus infection: precore mutants and its relation to viral genotypes and core mutations. Hepatology 22:1641-1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scaglioni, P. P., M. Melegari, and J. R. Wands. 1997. Biologic properties of hepatitis B viral genomes with mutations in the precore promoter and precore open reading frame. Virology 233:374-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scaglioni, P. P., M. Melegari, and J. R. Wands. 1997. Posttranscriptional regulation of hepatitis B virus replication by the precore protein. J. Virol. 71:345-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stuyver, L. J., S. A. Locarnini, A. Lok, D. D. Richman, W. F. Carman, J. L. Dienstag, and R. F. Schinazi. 2001. Nomenclature for antiviral-resistant human hepatitis B virus mutations in the polymerase region. Hepatology 33:751-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tacke, F., C. Trautwein, S. Zhao, M. Andreeff, M. P. Manns, A. Ganser, and P. Schöffski. 2002. Quantification of hepatic thrombopoietin mRNA transcripts in patients with chronic liver diseases shows maintained gene expression in different etiologies of liver cirrhosis. Liver 22:205-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tassopoulos, N. C., R. Volpes, G. Pastore, J. Heathcote, M. Buti, R. D. Goldin, S. Hawley, J. Barber, L. Condreay, D. F. Gray, et al. 1999. Efficacy of lamivudine in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-negative/hepatitis B virus DNA-positive (precore mutant) chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 29:889-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tong, S. P., C. Diot, P. Gripon, J. Li, L. Vitvitski, C. Trepo, and C. Guguen-Guillouzo. 1991. In vitro replication competence of a cloned hepatitis B virus variant with a nonsense mutation in the distal pre-C region. Virology 181:733-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yotsuyanagi, H., K. Hino, E. Tomita, J. Toyoda, K. Yasuda, and S. Iino. 2002. Precore and core promoter mutations, hepatitis B virus DNA levels and progressive liver injury in chronic hepatitis B. J. Hepatol. 37:355-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]