Abstract

Background

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are responsible for worldwide outbreaks and antibiotic treatments are problematic. The polysaccharide poly-(β-1,6)-N-acetyl glucosamine (PNAG) is a vaccine target detected on the surface of numerous pathogenic bacteria, including Escherichia coli. Genes encoding PNAG biosynthetic proteins have been identified in two other main pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae, Enterobacter cloacae and Klebsiella pneumoniae. We hypothesized that antibodies to PNAG might be a new therapeutic option for the different pan-resistant pathogenic species of CRE.

Methods

PNAG production was detected by confocal microscopy and its role in the formation of the biofilm (for E. cloacae) and as a virulence factor (for K. pneumoniae) was analysed. The in vitro (opsonophagocytosis killing assay) and in vivo (mouse models of peritonitis) activity of antibodies to PNAG were studied using antibiotic-susceptible and -resistant E. coli, E. cloacae and K. pneumoniae. A PNAG-producing strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an organism that does not naturally produce this antigen, was constructed by adding the pga locus to a strain with inactive alg genes responsible for the production of P. aeruginosa alginate. Antibodies to PNAG were tested in vitro and in vivo as above.

Results

PNAG is a major component of the E. cloacae biofilm and a virulence factor for K. pneumoniae. Antibodies to PNAG mediated in vitro killing (>50%) and significantly protected mice against the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-producing E. coli (P = 0.02), E. cloacae (P = 0.0196) and K. pneumoniae (P = 0.006), against K. pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing K. pneumoniae (P = 0.02) and against PNAG-producing P. aeruginosa (P = 0.0013). Thus, regardless of the Gram-negative bacterial species, PNAG expression is the sole determinant of the protective efficacy of antibodies to this antigen.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest antibodies to PNAG may provide extended-spectrum antibacterial protective activity.

Introduction

Initially described in Staphylococcus epidermidis, then in Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, as a product of the proteins encoded in the ica (Staphylococcus spp.)1 or pga (E. coli)2 loci, the surface polysaccharide poly-(β-1,6)-N-acetyl-glucosamine (PNAG) has now been detected in numerous Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.3 Previous studies have shown that monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) and polyclonal antibodies to PNAG can kill MDR and even pan-resistant strains of the Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC) in vitro and protect mice in a setting of peritonitis.4 PNAG antibodies were also protective in similar pre-clinical studies against potentially MDR bacterial species such as E. coli5 and Acinetobacter baumannii.6 In addition, genome analysis found that Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter cloacae and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia all contain an intact pga locus and may thus be able to produce PNAG.7 Therefore, antibodies to PNAG have the potential to prevent or treat a broad variety of infections caused by MDR Gram-negative bacteria.3,4 In the present work, we tested this hypothesis by analysing the ability of antibodies to PNAG to kill and protect against infections caused by carbapenemase-producing, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE). The study focused on the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1 (NDM-1)- and K. pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing strains, which represent major threats to patients in both the community and the hospital setting. We focused on three major Enterobacteriaceae species of clinical importance: E. coli, K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae.8,9 A confirmatory study was conducted using Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the only major MDR pathogen that does not naturally produce PNAG, to determine whether expression of PNAG using a cloned pga locus led to a significant protective effect of antibodies in this non-natural setting.

Materials and methods

A full description of the methods is available as Supplementary data at JAC Online. Bacterial strains, plasmids and primers are listed in Tables S1 and S2 (available as Supplementary data at JAC Online).

Bacterial strains

E. cloacae strains were provided by Astrid Rey, Sanofi, Toulouse, France. K. pneumoniae K2 was provided by Alan S. Cross, University of Maryland, Baltimore, USA. The E. coli, E. cloacae and K. pneumoniae NDM-1 strains were obtained from the CDC (USA) and the KPC strains were provided by Barry Kreiswirth, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark (USA). P. aeruginosa PA14 was available in the laboratory. The NDM-producing strains used in this study were resistant to all β-lactams tested (including carbapenems and aztreonam), ciprofloxacin, amikacin and gentamicin, and demonstrated MICs of colistin and polymyxin B ≤1 mg/L.10 The KPC-bearing K. pneumoniae strains all carried KPC-3 and belong to the epidemic ST258 clone, are endemic in New York and New Jersey11 and were resistant to all β-lactams tested, had intermediate resistance to amikacin (MIC 32 mg/L) and gentamicin (MIC 8 mg/L) and were susceptible to tetracyclines (doxycycline and minocycline), colistin (MIC 1 mg/L), tigecycline (MIC 1 mg/L) and polymyxin B (1 mg/L).

Genetic manipulations

Deletion of pgaC in K. pneumoniae was done following the method of Datsenko and Wanner.12 P. aeruginosa PA14 transposon (Tn) mutants were obtained from the PA14 Tn insertion library.13 Introduction of either a single pgaA gene or the entire pga locus was done by conjugation between P. aeruginosa PA14 and an E. coli Sm10 carrying pUCP18::pgaA or pUCP18::pga followed by selection on lysogeny broth (LB) agar supplemented with tetracycline (75 mg/L) and Irgasan (25 mg/L).

Confocal microscopy

Experiments followed previously described protocols with minor modifications.3

Flow cytometry

Bacteria were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) medium overnight at 37°C and then left at room temperature for 24 h before fixing with paraformaldehyde (PFA). Samples were then pelleted and washed with PBS and incubated with either MAb F429 to P. aeruginosa alginate14 directly conjugated to AF488 (2.5 μg/mL) or MAb F598 to PNAG15 directly conjugated to AF488 (2.5 μg/mL), then placed in PBS containing 0.5% BSA overnight at 4°C. Samples were then washed with PBS and resuspended in 500 μL of PBS and placed into flow cytometry tubes for FACS analysis.

Biofilm assays

Biofilm production was assessed as previously described4 by measuring the incorporation of crystal violet after growth of bacterial cultures in glass tubes at 37°C for 24 h containing TSB medium.

Opsonophagocytic activity of PNAG-specific antibodies against the major species of pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae

The opsonophagocytic assays followed published protocols16 except that the differentiated HL60 promyelocytic cell line (ATCC) was used as a source of phagocytes.3

Protection studies

Mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions and all animal experiments were conducted under protocols approved by the Harvard Medical Area Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

To evaluate the in vivo protective efficacy of antibody to PNAG, we used either an intraperitoneal or intravenous (via retro-orbital injection) infection model in mice, as described previously.17 Briefly, mice (C3H/HeN, female, 6–8 weeks of age) were injected intraperitoneally with PBS, 0.2 mL of normal goat serum (NGS), or PNAG-specific goat antiserum raised to a vaccine containing 9GlcNH2-TT17 24 and 4 h before infection. Bacteria were grown overnight in LB and then resuspended in sterile PBS to ∼5 × 108 to 5 × 109 cfu/0.2 mL.

Statistical analysis

Non-parametric data were evaluated by the Mann–Whitney U-test for two-group comparisons and by the Kruskal–Wallis test for multi-group comparisons, with Dunn's multiple comparison test for pairwise comparisons. Parametric data were analysed by t-tests (for two-group comparisons) or ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test for pair-wise comparisons. Survival analysis utilized the Kaplan–Meier method. All analyses used GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

PNAG production in E. cloacae and K. pneumoniae

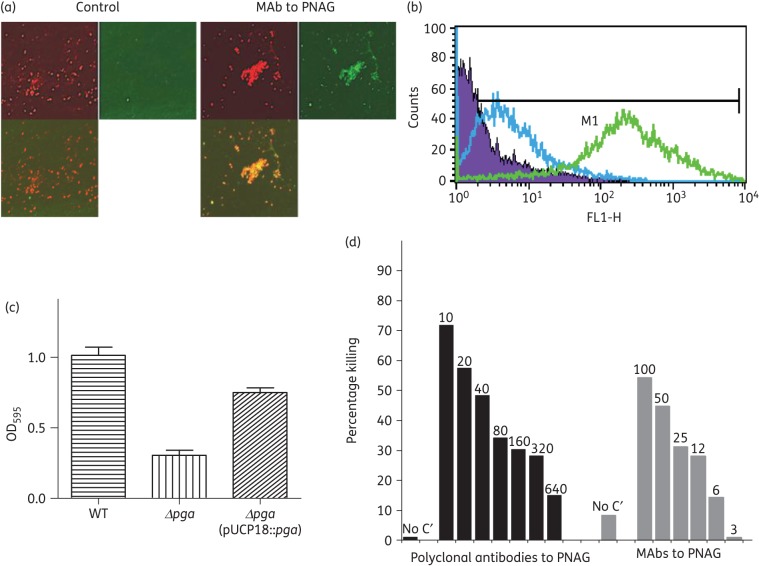

An initial bioinformatic analysis indicated an intact pga locus was present in the genomes of most available sequences of strains of E. cloacae and K. pneumoniae, predictive of PNAG expression. Using both immunofluorescence–confocal microscopy and FACS, PNAG was detected on the surface of E. cloacae, as evidenced by the binding of the human MAb F598 to PNAG (Figure 1). MAb F598 reactivity was retained after treatment of cells with chitinase, but lost after treatment with the PNAG-specific hydrolytic enzyme dispersin B18,19 (Figure S1), as well as after treatment with sodium metaperiodate, which can only degrade glucosamine residues linked β-(1→6) (Figure S1). PNAG produced by E. cloacae contributed to biofilm formation (Figure 1c), with significantly less production in the PNAG negative strain E. cloacae 2A ΔpgaC (P < 0.001). Biofilm production was restored in the E. cloacae ΔpgaC (pUCP18::pgaC) strain, in which the pgaC gene was provided by trans complementation (Figure 1c). Opsonic killing of E. cloacae 2A could be mediated by both polyclonal antibodies and the MAb to PNAG (Figure 1d). Identical results were obtained with a second strain, E. cloacae T (Figure S2a and b).

Figure 1.

E. cloacae and PNAG production. Detection of PNAG on the surface of E. cloacae 2a using immunofluorescence confocal microscopy (a) and flow cytometry (b). Binding of MAb F598 to PNAG conjugated to AF488 [green fluorescence in (a) and green curve in (b)]. No binding with the control MAb conjugated to AF488 was detected [lack of green fluorescence in (a) and blue curve in (b)]. In (a), SYTO 83 was used to visualize DNA (red fluorescence) and an overlay of red and green channels is presented. (c) Formation of biofilms after 2 days of growth at room temperature comparing E. cloacae 2a, E. cloacae 2a Δpga and E. cloacae 2a Δpga (pUCP18::pga). (d) Opsonophagocytic killing of E. cloacae 2a mediated by polyclonal antibodies and MAbs to PNAG. Bars represent mean percentage of killing relative to the control containing NGS or the control MAb F429. All standard deviations (not shown) were <15%. Assays were done in duplicate. C′, complement; absence of killing arbitrarily assigned as 1% killing. Dilutions of polyclonal antibodies and amounts (in μg) of MAb to PNAG tested are provided at the top of each bar.

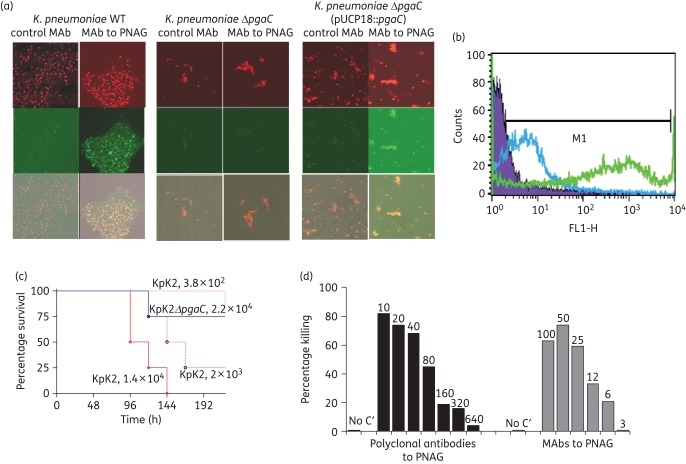

As with E. cloacae, the presence of the pga locus in K. pneumoniae K2 was associated with production of surface PNAG that was lost once the pgaC gene was deleted and restored when complemented back (Figure 2a–d). In K. pneumoniae, PNAG was also found to be a virulence factor with significantly fewer mice becoming moribund or dying (P < 0.01) in a mouse model of peritonitis when comparing animals infected with the K. pneumoniae K2 ΔpgaC strain with those infected with the WT strain. Antibodies to PNAG were also able to mediate opsonophagocytic killing of K. pneumoniae K2 (Figure 2(d).

Figure 2.

K. pneumoniae and PNAG production. Detection of PNAG on the surface of K. pneumoniae K2. (a) Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. (b) Flow cytometry analyses. Binding of MAb F598 to PNAG conjugated to AF488 [green fluorescence in (a) and green curve in (b)]. No binding of the control MAb [lack of green fluorescence in (a) and blue curve in (b)]. In (a), SYTO 83 was used to visualize DNA (red fluorescence). Bacteria tested in (a): K. pneumoniae K2, K. pneumoniae K2 ΔpgaC and K. pneumoniae K2 ΔpgaC (pUCP18::pgaC) (c). Impact of loss of PNAG on the virulence of K. pneumoniae K2: C3H/H3N mice (8/group) were challenged intraperitoneally with K. pneumoniae K2 (KpK2) at doses of 1.4 × 104, 2 × 103 or 3.8 × 102 cfu/mouse or with 2.2 × 104 cfu of K. pneumoniae K2 ΔpgaC (KpK2ΔpgaC). (d) Opsonophagocytic killing of K. pneumoniae K2 mediated by polyclonal antibodies or MAbs to PNAG. Bars indicate mean percentage of killing relative to controls containing NGS or the control MAb F429. All standard deviations (not shown) were <13%. Assays were done in duplicate. C′, complement; absence of killing arbitrarily assigned as 1% killing. Dilutions of polyclonal antibodies and amounts (in μg) of MAbs to PNAG tested are provided at the top of each bar.

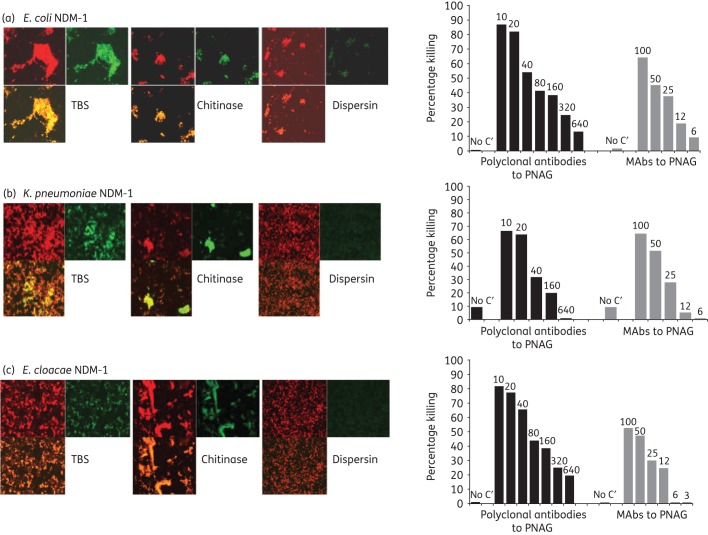

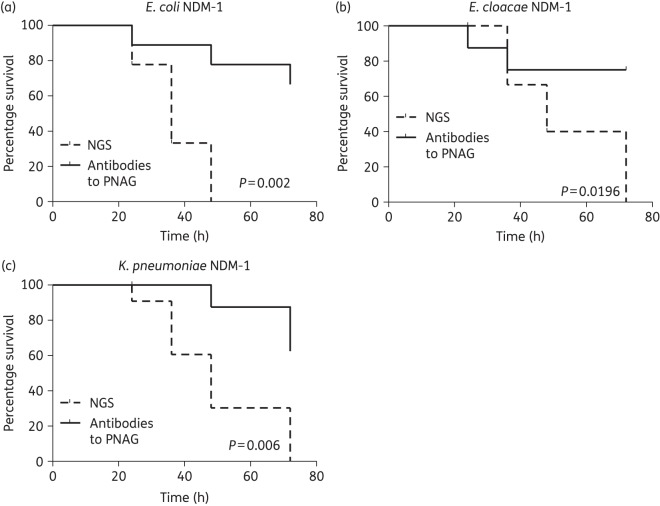

In vitro and in vivo activity of PNAG antibodies against NDM-1-producing E. coli, K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae

PNAG was expressed in all strains of E. coli, K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae carrying the carbapenemase-producing NDM-1 plasmid (Figure 3a–c, left panels). PNAG production allowed the in vitro killing of these bacteria by antibodies to this antigen (Figure 3a–c, right panels). In a mouse model of peritonitis, administration of antibodies to PNAG significantly protected against infections caused by NDM-1-producing strains of E. coli (108 cfu/mouse, P = 0.002), E. cloacae (5 × 109 cfu/mouse, P = 0.0196) and K. pneumoniae (108 cfu/mouse, P = 0.006) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

PNAG production by NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae and in vitro killing by PNAG antibodies. Detection of PNAG on the surface of NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae strains using immunofluorescence confocal microscopy (left panels). Binding of MAb F598 to PNAG conjugated to AF488 results in green fluorescence. SYTO 83 was used to visualize DNA (red fluorescence). Bacteria tested: NDM-1-producing E. coli, K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae (a, b, c left panels, respectively). Digestion with the PNAG-degrading enzyme dispersin B, but not a control enzyme, chitinase, resulted in loss of binding of MAb F598. Opsonophagocytic killing of NDM-1-producing E. coli, K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae (a, b, c, right panels, respectively) mediated by polyclonal antibodies or MAbs to PNAG. Bars represent mean percentage of killing relative to control containing NGS or the control MAb F429. All standard deviations (not shown) were <15%. Assays were done in duplicate. C′, complement; absence of killing arbitrarily assigned as 1% killing. Dilutions of polyclonal antibodies and concentrations (in μg) of MAbs to PNAG tested are provided at the top of each bar.

Figure 4.

In vivo protection by polyclonal antibodies to PNAG against E. coli NDM-1, E. cloacae NDM-1 and K. pneumoniae NDM-1 infections. C3H/H3N mice (8/group) were passively immunized with PNAG-specific goat antiserum intraperitoneally 24 and 4 h before intraperitoneal infection with E. coli NDM-1 (108 cfu/mouse), E. cloacae NDM-1 (5 × 109 cfu/mouse) or K. pneumoniae NDM-1 (5 × 108 cfu/mouse). Controls received NGS. P values by log-rank test.

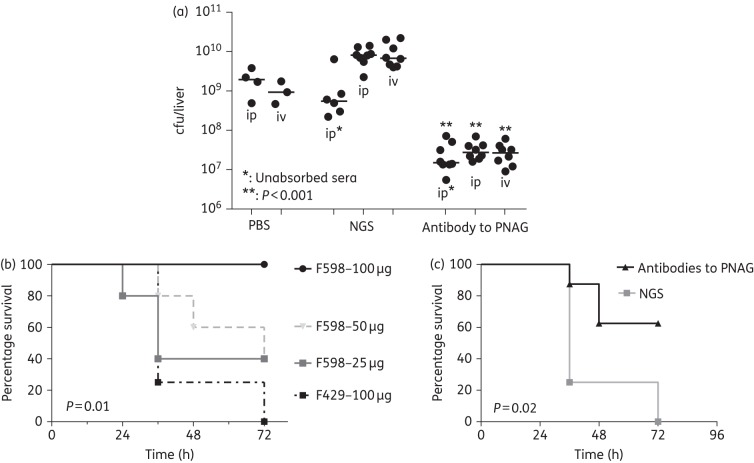

PNAG expression and protection against KPC-producing K. pneumoniae

In addition to NDM-1, KPC is the other major carbapenemase associated with pan-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. KPC are primarily produced by K. pneumoniae and KPC strains are responsible for both sporadic individual infections and severe outbreaks.20,21 Production of the plasmid-borne KPC did not interfere with PNAG production (Figure S3) and antibodies to PNAG were able to kill KPC-producing strains of K. pneumoniae in vitro.

For in vivo experiments, control and immune sera were injected intraperitoneally or intravenously followed by intraperitoneal challenge with 108 cfu of bacteria/mouse. Significantly fewer bacteria (P < 0.001) were recovered from the livers of the mice injected with PNAG-immune serum compared with the control serum (Figure 5a). The human MAb F598 to PNAG was next evaluated for protective efficacy. Various doses were injected intraperitoneally into mice followed by intravenous injection of 109 cfu of K. pneumoniae KPC (Figure 5b). Significantly fewer mice became moribund or died after receiving 100 μg of MAb F598 compared with mice immunized with 100 μg of the control MAb F429 (P = 0.01). Injecting lower doses of MAb F598 led to progressive reductions in protection. Polyclonal antibodies to the 9GlcNH2-TT vaccine were also significantly protective against intravenous challenge with K. pneumoniae KPC (P = 0.02, Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

In vivo protection by MAbs and polyclonal antibodies to PNAG against K. pneumoniae KPC infections. (a) C3H/H3N mice (n = 24) were passively immunized with PNAG-specific goat antiserum given intraperitoneally (ip) or intravenously (iv) 24 h and 4 h before intraperitoneal inoculation of K. pneumoniae KPC. Controls received NGS (n = 20) or PBS (n = 7). All sera were either intact or absorbed with K. pneumoniae K2ΔpgaC to remove antibodies to K. pneumoniae other than those to PNAG. The challenge dose was 108 cfu/mouse. P values by unpaired non-parametric t-test comparing NGS to immune serum in mice challenged by the same route. (b) C3H/H3N mice (8/group) were passively immunized with different amounts of the MAb to PNAG (from 25 to 100 μg) or MAb to P. aeruginosa alginate (100 μg) as a control then challenged intravenously with K. pneumoniae KPC (109 cfu/mouse). (c) Mice were injected intraperitoneally with PNAG-specific goat antiserum 24 and 4 h before inoculation with K. pneumoniae KPC. Controls received NGS. P values by log-rank test comparing MAb F598 (100 μg) with MAb F429 (100 μg) (b) or antibodies to PNAG to non-immune serum (c).

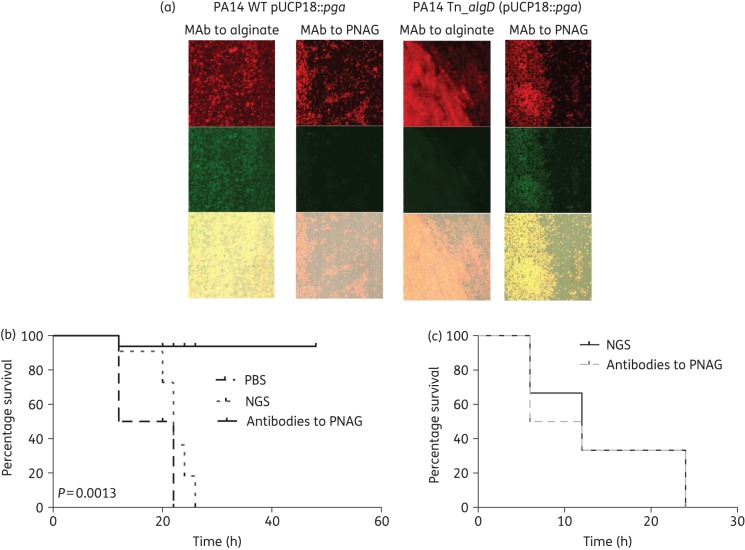

PNAG production in P. aeruginosa

To further validate that antibodies to PNAG could be protective against any Gram-negative pathogenic bacterial species producing PNAG, the pga locus from E. coli was introduced into WT and alginate-negative P. aeruginosa, a species that does not carry a native pga locus or produce PNAG. This antigen was not detected on the surface of WT P. aeruginosa (Figure S4), although alginate was, as previously reported.14 Interestingly, no PNAG was detected at the surface of WT PA14 after introduction of the E. coli pga locus (Figure 6a). We hypothesized that this could be due to production of alginate, a cell-surface polymer with a charge opposite to that of PNAG, and that elimination of alginate would allow PNAG production in the strain carrying pUCP18::pga. P. aeruginosa with a Tn insertion in the algD gene needed for alginate synthesis and transformed with pUCP18::pga had detectable PNAG on the surface (Figure 6b, right panel). No alginate was detected on this strain (Figure 6b, left panel). The same result was obtained with P. aeruginosa PA14 with Tn insertions in the algF or algJ gene: no PNAG was detected at the surface of alginate-deficient P. aeruginosa carrying only the pgaA gene on pUCP18. Identical results were obtained with another P. aeruginosa strain, FRD1. As with strain PA14, once the production of alginate was removed, PNAG was detected at the surface of the strains carrying pUCP18::pga.

Figure 6.

Impact of PNAG production in P. aeruginosa on protective efficacy of antibody to PNAG. (a) Detection of PNAG on the surface of P. aeruginosa. Binding of MAb F598 to PNAG conjugated to AF488 results in green fluorescence. SYTO 83 was used to visualize DNA (red fluorescence). The overlap of the green and red colour is presented in the bottom of each panel. WT P. aeruginosa PA14 carrying a cloned pga locus [PA14 WT (pUCP18::pga)] was positive for alginate production, but negative for PNAG. P. aeruginosa PA14 with a Tn insertion in the algD gene to inactivate alginate production (PA14 Tn::algD) with a cloned pga locus [PA14 Tn::algD (pUCP18::pga)] was negative for alginate, but positive for PNAG production. (b) C3H/H3N mice were passively immunized with PBS (4 mice), NGS (6 mice) or PNAG-specific goat immune serum (6 mice) intraperitoneally 24 and 4 h before intraperitoneal challenge with PNAG-producing P. aeruginosa PA14 Tn::algD (pUCP18::pga) (4 × 107 cfu/mouse). (c) C3H/H3N mice (n = 8/group) were passively immunized with either NGS or PNAG-specific goat immune serum intraperitoneally 24 and 4 h before intraperitoneal challenge with PNAG- and alginate-negative P. aeruginosa PA14 Tn::algD (5 × 108 cfu/mouse). P values by log-rank test comparing NGS with antibodies with PNAG.

In mice challenged intraperitoneally with 4 × 107 cfu of the PNAG-producing strain PA14 Tn::algD (pUCP18::pga), significantly fewer animals became moribund following passive transfer of antibody to PNAG compared with the group immunized with NGS or PBS (Figure 6b, P = 0.0013, log-rank test). Antibodies to PNAG did not have an effect on infection with the PNAG-negative parental strain PA14 Tn::algD (Figure 6c). A >1 log higher challenge dose of this strain, 5 × 108, was required to achieve similar levels of lethality compared with the strain producing PNAG, presumably due to the decreased virulence associated with loss of surface polysaccharides. Of note, the PNAG-producing P. aeruginosa PA14 is comparably virulent in mice to the alginate-producing WT PA14 strain.22

Discussion

Class A and B carbapenemases can hydrolyse nearly all β-lactams, including carbapenems, which are among the last drugs remaining for the treatment of MDR Gram-negative infections.23,24 K. pneumoniae producing these carbapenemases have spread globally and are now endemic in the USA, Israel, Greece and Italy.21 More recently, NDM-producing Enterobacteriaceae appeared and are disseminating from South Asia and Northern Africa.25 Mortality from invasive CRE infections reaches 40%.26 This situation demands new treatments for these infections, particularly using approaches such as immunotherapy, which likely has the advantage of being independent of the issues associated with the emergence and dissemination of antibiotic resistance. However, most immunotherapies are limited because antibodies usually target an antigen specific to one bacterial species or strain within a species. Thus, no immunotherapy has ever been developed with the potential to have a broad spectrum in the same manner as mainstream antibiotics such as β-lactams, aminoglycosides or fluoroquinolones. Indeed, for Gram-negative bacteria, the most effective immunological approaches target highly variable antigens such as capsules and LPS O polysaccharides, making it quite challenging to produce comprehensive immunotherapies for these organisms. This situation can now be addressed as it has been demonstrated that a chemically and structurally conserved surface polysaccharide, PNAG, is present on many microbial pathogens, and antibodies raised to specific glycoforms of this antigen can provide effective immunotherapy in laboratory animal settings.3–5,7,27 This approach was extended and further validated in this study by showing that PNAG-expressing MDR Gram-negative bacteria can be killed by antibodies to PNAG and protection achieved in mouse models, thus making immune effectors to this antigen an extended-spectrum immunotherapeutic targeting MDR pathogens.

This conclusion is supported by the in vitro and in vivo efficacy of PNAG antibodies against NDM-1 and KPC-producing Enterobacteriaceae species commonly responsible for human infections. A further proof of principle used P. aeruginosa producing PNAG to confirm that antibodies to this antigen were protective even in a non-natural setting of PNAG production. PNAG also contributed to biofilm production by E. cloacae and was a virulence factor in a murine model of K. pneumoniae infection. Antibodies to PNAG mediated opsonophagocytic killing in vitro and protection in vivo against all WT and MDR strains tested using different challenge routes. While OXA-48-type carbapenem-hydrolysing class D β-lactamase-producing strains are increasingly reported in enterobacterial species,28 they were not tested in this study. Nonetheless, the constellation of data presented indicate the potential to use immunotherapy against PNAG as a broad-spectrum antibody against multiple pathogens and that its efficacy will be unaffected by the mechanism of antibiotic resistance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Antibodies to PNAG: in vivo activity against MDR and pan-resistant Gram-negative bacteria

| Bacterial species | Method of immunization | Challenge route | Animal model |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli NDM-1 | intraperitoneal | intraperitoneal | lethalitythis study |

| E. cloacae NDM-1 | intraperitoneal | intraperitoneal | lethalitythis study |

| K. pneumoniae KPC | intraperitoneal | intraperitoneal | lethalitythis study |

| intraperitoneal | intravenous | lethalitythis study | |

| intraperitoneal | intravenous | bacteraemiathis study | |

| K. pneumoniae NDM-1 | intraperitoneal | intraperitoneal | lethalitythis study |

| PNAG-producing P. aeruginosa | intraperitoneal | intraperitoneal | lethalitythis study |

| A. baumannii | intranasal | intranasal | pneumonia |

| intravenous | intravenous | bacteraemia6 | |

| B. cepacia complex | intraperitoneal | intraperitoneal | lethality4 |

Another advantage of this approach is that in this study, and in previous reports,5,6,16,29–31 PNAG is frequently found to be a virulence factor when the virulence of PNAG-negative strains is compared with parental WT strains in animal models of infection. This reduces the impact of the loss of PNAG production to avoid immune effectors, inasmuch as virulence will likely be frequently compromised. This outcome is in contrast to our recent demonstration22,32 that acquisition of antibiotic resistance was associated with an increase in virulence in animal models of infection, a worrisome finding in that the emergence of spread of resistant strains could also promote the spread of more virulent bacterial pathogens.

A Phase I clinical trial evaluating the safety and pharmacokinetics of MAb F598 to PNAG has been successfully completed,33 and the design of a Phase II trial is currently being finalized. In addition, the production of a vaccine to generate functional antibodies to PNAG in humans will be completed and tested in 2016. Therefore, with strong preclinical data to support the development of the concept that PNAG is a target for broad-spectrum immunotherapies against infectious agents, an efficient way to possibly treat many of the major Gram-negative pathogenic organisms, including those with MDR or pandrug-resistant (PDR) phenotypes, may be realized.

Funding

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants EY016104 and AI057159 (a component of Award U54A1057159) (to G. B. P.). This work was also supported by the AXA Research Fund and the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (to D. R.), awards from the William Randolph Hearst Fund (to D. R.) and the Hood Foundation (to D. S.).

Transparency declarations

D. S. and C. C.-B. are inventors of intellectual properties (use of human MAb to PNAG and use of PNAG vaccines) that are licensed by Brigham and Women's Hospital to Alopexx Vaccine, LLC, and Alopexx Pharmaceuticals, LLC. As inventors of intellectual properties, D. S. and C. C.-B. also have the right to receive a share of licensing-related income (royalties, fees) through Brigham and Women's Hospital from Alopexx Pharmaceuticals, LLC, and Alopexx Vaccine, LLC. G. B. P. is an inventor of intellectual properties (human MAb to PNAG and PNAG vaccines) that are licensed by Brigham and Women's Hospital to Alopexx Vaccine, LLC, and Alopexx Pharmaceuticals, LLC, entities in which G. B. P. also holds equity. As an inventor of intellectual properties, G. B. P. also has the right to receive a share of licensing-related income (royalties, fees) through Brigham and Women's Hospital from Alopexx Pharmaceuticals, LLC, and Alopexx Vaccine, LLC. G. B. P.'s interests were reviewed and are managed by the Brigham and Women's Hospital and Partners Healthcare in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. All other authors: none to declare.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.McKenney D, Hubner J, Muller E et al. The ica locus of Staphylococcus epidermidis encodes production of the capsular polysaccharide/adhesin. Infect Immun 1998; 66: 4711–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang X, Preston JF 3rd, Romeo T. The pgaABCD locus of Escherichia coli promotes the synthesis of a polysaccharide adhesin required for biofilm formation. J Bacteriol 2004; 186: 2724–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cywes-Bentley C, Skurnik D, Zaidi T et al. Antibody to a conserved antigenic target is protective against diverse prokaryotic and eukaryotic pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: E2209–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skurnik D, Davis MR Jr, Benedetti D et al. Targeting pan-resistant bacteria with antibodies to a broadly conserved surface polysaccharide expressed during infection. J Infect Dis 2012; 205: 1709–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cerca N, Maira-Litran T, Jefferson KK et al. Protection against Escherichia coli infection by antibody to the Staphylococcus aureus poly-N-acetylglucosamine surface polysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 7528–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bentancor LV, O'Malley JM, Bozkurt-Guzel C et al. Poly-N-acetyl-β-(1–6)-glucosamine is a target for protective immunity against Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Infect Immun 2012; 80: 651–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roux D, Pier GB, Skurnik D. Magic bullets for the 21st century: the reemergence of immunotherapy for multi- and pan-resistant microbes. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012; 67: 2785–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woerther PL, Burdet C, Chachaty E et al. Trends in human fecal carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the community: toward the globalization of CTX-M. Clin Microbiol Rev 2013; 26: 744–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wailan AM, Paterson DL. The spread and acquisition of NDM-1: a multifactorial problem. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2014; 12: 91–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasheed JK, Kitchel B, Zhu W et al. New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19: 870–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen L, Chavda KD, Al Laham N et al. Complete nucleotide sequence of a blaKPC-harboring IncI2 plasmid and its dissemination in New Jersey and New York hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57: 5019–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97: 6640–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liberati NT, Urbach JM, Miyata S et al. An ordered, nonredundant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 transposon insertion mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103: 2833–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pier GB, Boyer D, Preston M et al. Human monoclonal antibodies to Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate that protect against infection by both mucoid and nonmucoid strains. J Immunol 2004; 173: 5671–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly-Quintos C, Cavacini LA, Posner MR et al. Characterization of the opsonic and protective activity against Staphylococcus aureus of fully human monoclonal antibodies specific for the bacterial surface polysaccharide poly-N-acetylglucosamine. Infect Immun 2006; 74: 2742–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kropec A, Maira-Litran T, Jefferson KK et al. Poly-N-acetylglucosamine production in Staphylococcus aureus is essential for virulence in murine models of systemic infection. Infect Immun 2005; 73: 6868–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gening ML, Maira-Litran T, Kropec A et al. Synthetic β-(1→6)-linked N-acetylated and nonacetylated oligoglucosamines used to produce conjugate vaccines for bacterial pathogens. Infect Immun 2010; 78: 764–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan JB, Velliyagounder K, Ragunath C et al. Genes involved in the synthesis and degradation of matrix polysaccharide in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae biofilms. J Bacteriol 2004; 186: 8213–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fazekas E, Kandra L, Gyemant G. Model for β-1,6-N-acetylglucosamine oligomer hydrolysis catalysed by DispersinB, a biofilm degrading enzyme. Carbohydr Res 2012; 363: 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munoz-Price LS, Poirel L, Bonomo RA et al. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet 2013; 13: 785–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nordmann P, Cuzon G, Naas T. The real threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing bacteria. Lancet 2009; 9: 228–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roux D, Danilchanka O, Guillard T et al. Fitness cost of antibiotic susceptibility during bacterial infection. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7: 297ra114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poirel L, Pitout JD, Nordmann P. Carbapenemases: molecular diversity and clinical consequences. Future Microbiol 2007; 2: 501–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walther-Rasmussen J, Hoiby N. Class A carbapenemases. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007; 60: 470–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumarasamy KK, Toleman MA, Walsh TR et al. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet 2010; 10: 597–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doi Y, Paterson DL. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 36: 74–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maira-Litran T, Kropec A, Goldmann DA et al. Comparative opsonic and protective activities of Staphylococcus aureus conjugate vaccines containing native or deacetylated staphylococcal poly-N-acetyl-β-(1–6)-glucosamine. Infect Immun 2005; 73: 6752–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poirel L, Potron A, Nordmann P. OXA-48-like carbapenemases: the phantom menace. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012; 67: 1597–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen KM, Chiang MK, Wang M et al. The role of pgaC in Klebsiella pneumoniae virulence and biofilm formation. Microb Pathog 2014; 77: 89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye L, Zheng X, Zheng H. Effect of sypQ gene on poly-N-acetylglucosamine biosynthesis in Vibrio parahaemolyticus and its role in infection process. Glycobiology 2014; 24: 351–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin MH, Shu JC, Lin LP et al. Elucidating the crucial role of poly N-acetylglucosamine from Staphylococcus aureus in cellular adhesion and pathogenesis. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0124216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skurnik D, Roux D, Cattoir V et al. Enhanced in vivo fitness of carbapenem-resistant oprD mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa revealed through high-throughput sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 20747–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vlock D, Lee JC, Kropec A et al. Pre-clinical and initial Phase I evaluations of a fully human monoclonal antibody directed against the PNAG surface polysaccharide on Staphylococcus aureus. In: Abstracts of the Fiftieth Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Boston, MA, USA, 2010. Abstract G1-1654/329 American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.