Abstract

Objectives

The global emergence of OXA-48-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae clones is a significant threat to public health. We used WGS and phylogenetic analysis of Spanish isolates to investigate the population structure of blaOXA-48-like-expressing K. pneumoniae ST11 and ST405 and to determine the distribution of resistance genes and plasmids encoding blaOXA-48-like carbapenemases.

Methods

SNPs identified in whole-genome sequences were used to reconstruct phylogenetic trees, identify resistance determinants and de novo assemble the genomes of 105 blaOXA-48-like-expressing K. pneumoniae isolates.

Results

Genome variation was generally lower in outbreak-associated isolates compared with those associated with sporadic infections. The relatively limited variation observed within the outbreak-associated isolates was on average 7–10 SNPs per outbreak. Of 24 isolates from suspected sporadic infections, 7 were very closely related to isolates causing hospital outbreaks and 17 were more diverse and therefore probably true sporadic cases. On average, 14 resistance genes were identified per isolate. The 17 ST405 isolates from sporadic cases of infection had four distinct resistance gene profiles, while the resistance gene profile differed in all ST11 isolates from sporadic cases. Sequence analysis of 94 IncL/M plasmids carrying blaOXA-48-like genes revealed an average of two SNP differences, indicating a conserved plasmid clade.

Conclusions

Whole-genome sequence analysis enabled the discrimination of outbreak and sporadic isolates. Significant inter-regional spread within Spain of highly related isolates was evident for both ST11 and ST405 K. pneumoniae. IncL/M plasmids carrying blaOXA-48-like carbapenemase genes were highly conserved geographically and across the outbreaks, sporadic cases and clones.

Introduction

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a major cause of nosocomial infections, particularly in ICUs.1 Over the last two decades, K. pneumoniae that encode antibiotic resistance genes, including those determining carbapenemase production, have emerged.2 Carbapenem resistance mediated by plasmid-encoded carbapenemases is an important threat to public health, as these enzymes can hydrolyse nearly all commonly used β-lactam antibiotics. The most common carbapenemases in the Enterobacteriaceae are KPC (class A according to the Ambler β-lactamase classification based on amino acid sequences), VIM, IMP and NDM (class B) and the OXA-48 types (class D). OXA-48 was first reported in a clinical isolate of K. pneumoniae from a patient hospitalized in Turkey in 20013 and is increasingly reported in many countries.4–8 Their prevalence in some European countries has increased in just a few years and many outbreaks have been reported,9 which is in contrast to the relatively few reports from North America10 and Canada.11 The first reported case of OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae in Spain was in 2009.12 Since then, multiple OXA-48-producing multilocus STs, including ST11, ST405, ST15 and ST16, have spread within and between hospitals.8,12–16 Concurrently, additional carbapenemase variants, related to OXA-48, have been identified, such as OXA-181, OXA-163, OXA-204, OXA-245, OXA-244 and OXA-246.8,17–19 The number of OXA-48-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates (mainly K. pneumoniae) submitted to the Antibiotic Reference Laboratory at the Centro Nacional de Microbiología increased from 0 in 2010 to 1132 in 2014. The most prevalent blaOXA-48-carrying K. pneumoniae clones isolated in Spain were ST11 and ST405.20

The application of WGS to distinguish between pathogen variants has improved our understanding of the epidemiology and evolution of bacterial pathogens.21 Sequencing technologies have advanced to the point that data can now be generated in a clinically relevant time frame.22 In this study, we applied this approach linked to phylogenetic analysis to analyse the population structure, spread and distribution of resistance genes in XDR K. pneumoniae isolates associated with outbreaks and sporadic infections and which carry blaOXA-48-like carbapenemase genes.

Materials and methods

Strain collection and DNA extraction

Study isolates came from patients admitted to 12 hospitals located across the country (6 located in the central region, 3 located in the north-east region, 2 located in the north-west region and 1 located in the southern region). One hundred and five K. pneumoniae isolates expressing blaOXA-48-like genes (blaOXA-48 carbapenemase gene and their variants) that were submitted to the Antibiotic Reference Laboratory under the active Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance Program over a 4 year period (2009–12) were sequenced. Strains were selected to include representative isolates from large hospital outbreaks up to a maximum of 30 isolates per hospital (Outbreaks A, B, B2 and C) and sporadic infections (Table 1) of the most prevalent multilocus STs carrying blaOXA-48-like genes in Spain. Seventy isolates (67%) were from three different hospitals in which large outbreaks of K. pneumoniae carrying blaOXA-48-like genes have occurred.8 The remaining 35 isolates had no apparent link to an outbreak and were suspected sporadic infections. Outbreaks A and B were previously characterized by MLST and PFGE in our reference laboratory (data not shown). Isolates were cultured on 5% sheep blood agar and MacConkey agar (BBL, Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, MD, USA) to assess purity. DNA was then extracted using an ADN QIAamp® DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Table 1.

Description of 70 strains isolated in persistent outbreaks and 35 strains isolated in sporadic infections of K. pneumoniae expressing blaOXA-48-like genes (all strains isolated from different patients)

| Isolates | Hospital (region of isolation) | Carbapenemase type | Number of isolates | Multilocus STs | Date of isolation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outbreak A | H4 (NE) | blaOXA-48 | 30 | ST405 | 16/12/10 to 18/11/11 |

| Outbreaks B and B2a | H8 (S) | blaOXA-48/245 | 29 | ST11, ST437 | 18/10/11 to 03/05/12 |

| Outbreak C | H3 (C) | blaOXA-48 | 11 | ST405 | 26/12/11 to 06/09/12 |

| Sporadic infection | H10 (NW) | blaOXA-48 | 3 | ST16 | 08/04/11 to 22/06/12 |

| H2 (NE) | blaOXA-48 | 5 | ST405 | 06/07/11 to 03/10/12 | |

| H7 (C) | blaOXA-48 | 5 | ST11, ST405 | 18/08/11 to 20/11/12 | |

| H1 (C) | blaOXA-48 | 3 | ST11, ST405 | 24/06/11 to 30/10/12 | |

| H5 (C) | blaOXA-48 | 2 | ST405 | 13/03/12 to 25/06/12 | |

| H3 (C) | blaOXA-48 | 1 | ST11 | 24/08/12 | |

| H6 (C) | blaOXA-48 | 6 | ST11, ST405, ST846 | 20/03/12 to 28/10/12 | |

| H11 (NW) | blaOXA-48 | 2 | ST16 | 09/01/12 to 16/01/12 | |

| H9 (NE) | blaOXA-245 | 1 | ST11 | 23/05/12 | |

| H12 (C) | blaOXA-48 | 2 | ST15 | 27/12/12 to 02/01/13 | |

| H8 (S) | blaOXA-244 | 1 | ST392 | 05/03/12 | |

| H4 (NE) | blaOXA-48 | 4 | ST405, ST13 | 16/10/12 to 26/11/12 |

C, central region; NW, north-west region; NE, north-east region; S, southern region.

aAt the same time that Outbreak B was detected in H8, this hospital experienced another separate and ongoing outbreak (assigned as Outbreak B2, six isolates).

Genomic library preparation and nucleotide sequence determination

Multiplex libraries with a 200 bp insert were prepared using 96 unique index tags and then sequenced to generate 54 or 76 bp paired-end reads. Cluster formation, primer hybridization and sequencing reactions were based on reversible terminator chemistry using a HiSeq 2000 system (Illumina) according to standard protocols.23,24 Raw sequence data were submitted to the European Nucleotide Archive (Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online).

Sequence analysis

Sequence reads were mapped to the chromosome of K. pneumoniae NTUH-K204425 (accession no. NC_012731.1) with an insert size between 50 and 400 bp using SMALT (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/science/tools/smalt-0). Sequence reads mapped to an average of 93.01% of the reference genome, with a mean depth of 91.4× in mapped regions across the isolates (Table S1). SNPs were identified as described by Harris et al.23 SNPs called in integrative and conjugative elements and phages, which were identified using a prophage locus prediction tool,26 were excluded (Table S2). Sequences suspected of arising from homologous recombination were identified based on elevated SNP density using Gubbins software.27 After the removal of sequences in regions of possible recombination and mobile elements, we generated a concatenated alignment with 74 716 SNP sites. For plasmid sequence analysis, all paired-end sequence reads of each isolate were mapped to a multi-Fasta pseudomolecule, including the chromosome of K. pneumoniae NTUH-K2044, K. pneumoniae plasmid pOXA-48 (reference accession code NC_019154.1) and K. pneumoniae plasmid pUUH239.2 (reference accession code CP002474), as described previously. Isolates with no reads mapping to the length of the plasmid were interpreted as not having the corresponding feature. The same methodology as described earlier was used to identify SNPs.23 The multilocus STs of the 105 isolates were assigned from the sequence data as described previously.28

Phylogenetic analysis

A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using SNPs within the core genome using RAxML v7.0.429 with a general time-reversible (GTR) model and gamma correction for among-site rate variation. The support for the nodes on the trees was assessed using 100 bootstrap replicates. The SNP alignment of each ST was used to recalculate individual maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees.

Bayesian analysis

The estimation of substitution rates for each cluster was performed on SNP alignments using the Bayesian MCMC framework, Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees (BEAST).30 Various combinations of population size change models and molecular clock models were compared to identify the model that best fit the data. In all cases, Bayes factors showed strong support (Bayes factor <200) for the use of a skyline31 model of population size change, a relaxed, uncorrelated lognormal clock,32 which allows the evolutionary rates to change among the branches of the tree, and a GTR substitution model with gamma correction for the among-site rate variation. In all cases, three independent chains were run for 250 million generations each and sampled every 10 000 steps. Convergence was checked for each chain both by checking effective sample size values were >200 for all parameters and checking that each run converged in similar results, the three chains were combined using LogCombiner,30 with the initial 25 million generations removed from each as a burn-in.

Determination of antimicrobial resistance gene sequences

A resistance gene pseudomolecule was prepared by the concatenation of 2881 resistance genes (nucleotide sequence) downloaded from the web-based tool ResFinder33 (http://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ResFinder/) with minor curation (data not shown). An in-house script was used to identify sequences in each sample assembly with similarity to those in the pseudomolecule using BLAST and mapping of the raw data per sample was performed to assess coverage of the resistance gene(s) in question.34 The resistance pseudomolecule contained the accessory genes implicated in antibiotic resistance; in the case of core genes such as gyrA and parC, nucleotide sequences were aligned separately in Seaview V4.135 using Muscle.36 The sequences were translated into proteins to detect the mutations in quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDRs) associated with fluoroquinolone resistance.

De novo assembly and genome comparisons

Paired-end Illumina sequence data were assembled de novo using Velvet;37 parameters were optimized to give the highest N50 value. All of the draft genomes generated were ordered using the Artemis Comparison Tool (ACT)38 and the draft plasmid genomes were ordered using Abacas.39 The assembled and ordered genomes were annotated using an in-house perl script (annotations_update.pl, SANGER) that transfers annotations on the basis of BLASTN (BLASTNucleotide) similarity. Annotation, analysis and comparison of sequences were performed using both Artemis40 and ACT.38

Results and discussion

Phylogenetic analysis of carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae

We determined the whole-genome sequence of 105 Spanish K. pneumoniae isolates expressing blaOXA-48-like genes to build a comprehensive picture of the relationships between the isolates based on MLST and phylogeny.23 100 949 high-quality SNPs were identified in the genome sequences of these 105 K. pneumoniae isolates with reference to the whole-genome sequence of K. pneumoniae strain NTUH-K2044, after removal of confounding SNPs in mobile genetic elements, phages and repetitive sequences. Additionally, regions of recombination were identified, mainly in isolates belonging to clonal complex (CC) 11 (ST11 and ST437; Table S1), and removed from the analysis to facilitate identification of the core phylogeny. The remaining 74 716 SNPs were used to reconstruct a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree (Figure S1).

Using this approach, the isolates were grouped into three major clusters (Clusters I, II and III) based on phylogenetic reconstruction. Cluster I contained 58 isolates (all belonging to ST405) from eight hospitals located in the central and north-east regions of Spain. Cluster II contained 36 isolates, 30 ST11 and 6 ST437, from four hospitals located mainly in central and southern Spain. The five Cluster III isolates belonging to ST16 were isolated in the north-west region of Spain. The remaining six isolates belonged to other multilocus STs (ST15, two isolates; ST846, two isolates; ST13, one isolate; and ST392, one isolate) (Figure S1). Cluster I isolates differed from each other by an average of 28 SNPs (range, 1–67) and Cluster II by 20 SNPs (range, 0–109). Cluster I and II isolates were distinct by an average of 15 905 SNPs that clearly demarcated two clades. The number of SNPs detected within ST405 and ST11 is consistent with the core genome genetic diversity described previously for K. pneumoniae ST258;41 however, in our collection, both ST11 and ST405 were less diverse than ST258.

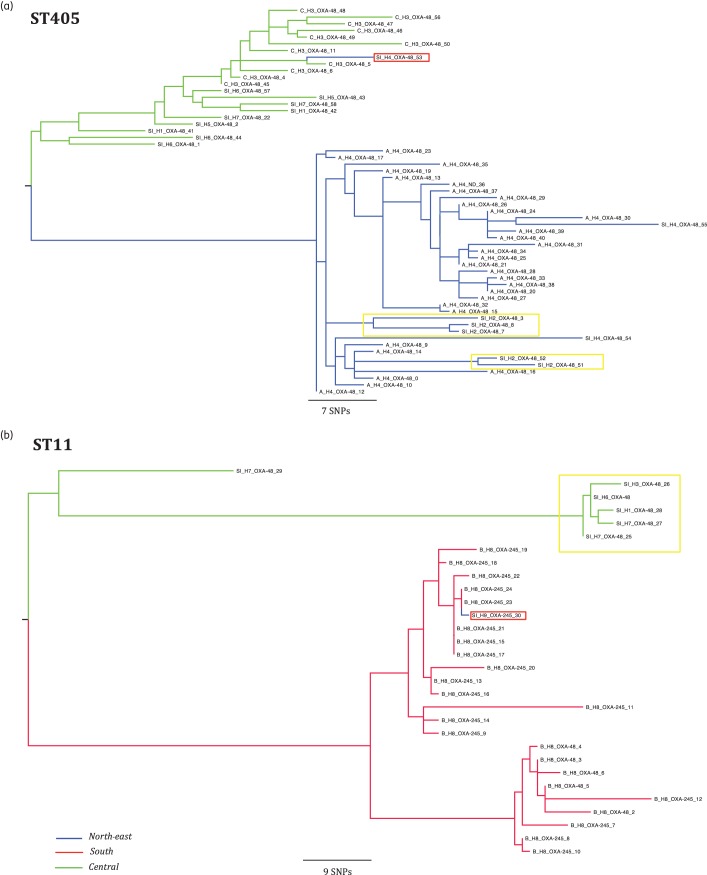

To analyse the phylogeny of the most prevalent clones in this study, ST405 and ST11, we identified the informative SNPs with reference to the earliest K. pneumoniae isolated and these were used to reconstruct a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree for each ST (Figure 1). Isolates of ST405 causing Outbreak A differed from each other on average by 10 SNPs (range, 1–30); the same average was observed for isolates causing Outbreak C (10 SNPs, range 3–22), in comparison with a mean of 40 SNPs (range 1–77) for the ST405 isolates causing infections defined epidemiologically as sporadic. All ST405 isolates causing Outbreak A (H4) were grouped in the same cluster (Figure 1a), although there were also five additional ST405 ‘sporadic cases’ from H2 that were grouped along with Outbreak A isolates (isolates highlighted in a yellow rectangle; Figure 1a), probably implicating them in the same outbreak. There were three additional sporadic cases involving the ST405 isolates in H4 (SI_H4_OXA-48 isolates; Figure 1a), two of the isolates responsible for these cases were grouped with the Outbreak A isolates and the other with Outbreak C isolates (H3, isolate highlighted in a red rectangle; Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Population structure of ST11 and ST405 K. pneumoniae expressing blaOXA-48-like genes. Maximum-likelihood trees showing the relationship between isolates of ST405 and ST11; branch length is indicative of the number of SNPs. The name of each strain includes a letter representative of the epidemiological state [A, B, B2 and C for strains isolated in an outbreak and sporadic infection (SI) for isolated cases], hospital of isolation (H1–H9) and carbapenemase expressed. The colour of each branch represents the region of isolation. Cases of suspected inter-regional spread are highlighted in a red rectangle and cases of suspected interhospital spread are highlighted in a yellow rectangle.

ST11 isolates causing Outbreak B differed from each other by an average of 7 SNPs (range, 0–18), in comparison with a mean of 20 SNPs (range, 2–42) in all ST11 isolates associated with sporadic infections. The vast majority of the ST11 isolates causing Outbreak B (H8) were grouped in the same cluster (red branches in the tree; Figure 1b); one additional ST11 isolate from H9 (located in the north-east region of Spain) was grouped with Outbreak B (isolate highlighted in a red rectangle; Figure 1b). In summary, the average number of SNPs obtained in a pairwise comparison was at least three times lower in the isolates associated with outbreaks compared with isolates reported as sporadic infections both in ST405 and ST11.

SNP typing provided a higher-resolution and more detailed epidemiological perspective of K. pneumoniae expressing blaOXA-48-like genes compared with MLST or PFGE. For example, isolates causing Outbreak A generated an identical pulsotype, as was the case for isolates from Outbreak B, although this pattern was different from Outbreak A (data not shown). Our study and others showed that whole-genome sequence gives the benefit of a more detailed description of isolates within an outbreak compared with conventional methods,42 providing the information required to design clone-specific probes for rapid PCR-typing allowing the rapid identification required for local outbreak surveillance.43

In our study, SNP typing resulted in the grouping of some isolates reported as sporadic cases together with isolates associated with outbreaks, suggesting that the same clone may be spreading between different healthcare institutions due to the interchange of patients and/or healthcare workers.44 Moreover, we detected two cases of inter-regional spread of ST405 and ST11 isolates (one case each), suggesting that the epidemiological status of K. pneumoniae expressing blaOXA-48-like genes has changed from local or regional to inter-regional spread in Spain. Very recently,45 it has been shown that K. pneumoniae producing OXA-48 have spread very quickly in Spain and other European countries. Our data based on WGS provide new detailed molecular evidence strongly suggesting that the most prevalent OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae ST11 and ST405 isolates are quickly spreading by producing local and regional outbreaks as well as sporadic cases. These data, along with the large number of antibiotic resistance genes detected by WGS, should be taken into account for surveillance purposes.

Evolutionary history of clusters

In order to reconstruct the evolutionary history over time from DNA sequences within ST405 and ST11, we performed temporal analysis with BEAST, a methodology for linking phylogeny to evolutionary time and calculating substitution rate.30 The mean substitution rate, assuming a Bayesian skyline model of population size change and a relaxed lognormal molecular clock, corresponded to an accumulation of ∼12 and ∼11 SNPs per genome per year for isolates belonging to ST11 and ST405, respectively. This rate is similar to that described previously for Staphylococcus aureus22 and 5–10-fold higher than for Salmonella.46

No regions with high SNP density were detected in the isolates belonging to ST405; however, if regions of high SNP density were included in the analysis of ST11 isolates, a substitution rate of 30 SNPs per genome per year was observed, supporting the idea that these SNPs probably arose due to recombination. In a previous analysis of the population determined by eBURST, K. pneumoniae CC258/11 (particularly ST11) was described as one of the most internationally prevalent and MDR CCs.47 Thus, ST11 appears to be an older and more widely distributed clone in comparison with ST405, as ST11 was described in 2005 as CTX-M-producing K. pneumoniae,48 but the first report of ST405 in 2013 associated it with K. pneumoniae expressing blaOXA-48.8 Sequence diversity outside of suspected regions of recombination of the ST405 and ST11 clades is similar in our strain collections. This is probably due to the clonal nature of the isolates that were included in this study, which do not necessarily reflect the true diversity of ST11 and ST405 globally.

Identification and distribution of resistance genes

The profile of genes conferring resistance to antimicrobial agents (resistome) was determined on the basis of WGS data and all of the resistance genes identified in this study are listed in Table S1. We found a good correlation between the genetic profile and phenotypic resistance profile for β-lactam, aminoglycoside and fluoroquinolone antibiotics (Table S1). Among the entire isolate collection, only three types of genes were found on the chromosome (blaSHV, oqx and fosA); all other resistance genes were located in plasmids. The constitutive oqxAB operon encodes an efflux system that confers resistance to quinolones and chloramphenicol and was originally identified on a plasmid carried by Escherichia coli. In K. pneumoniae, this operon has been reported with high prevalence (97%–100%) and is located on the chromosome, indicating that K. pneumoniae could be a reservoir for oqxAB.49 Overexpression of oqxAB may be required for virulence.50

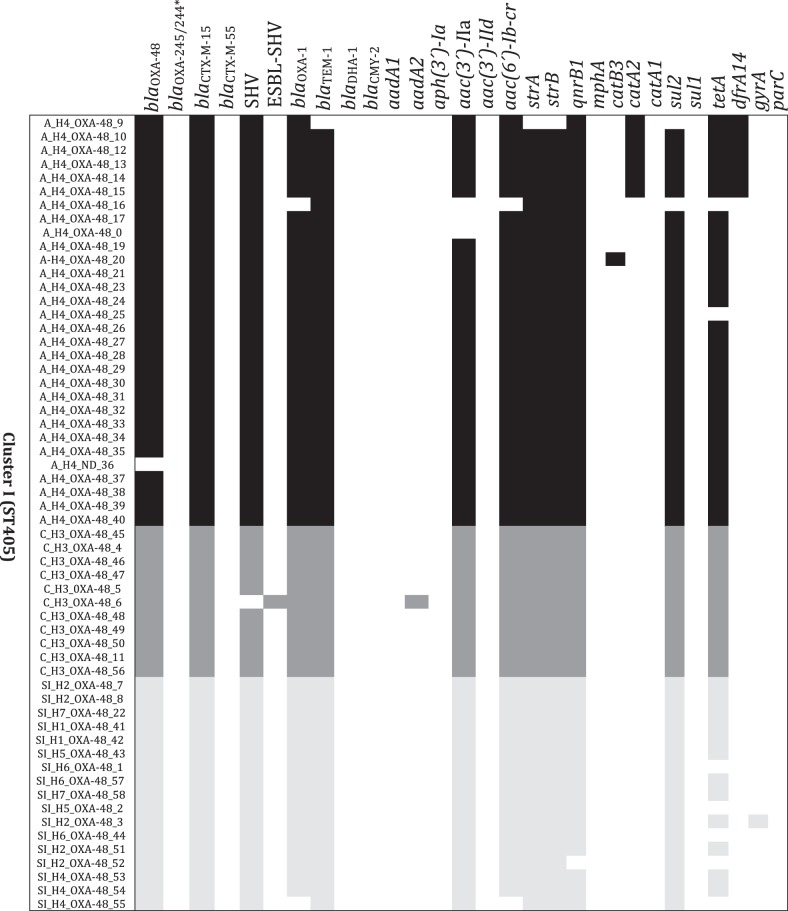

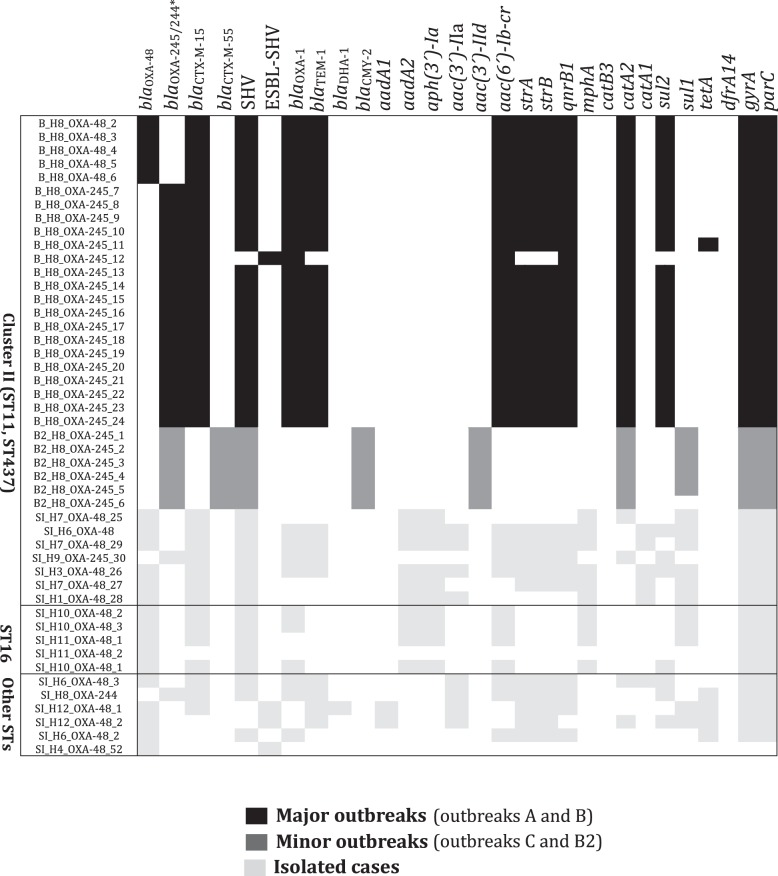

Four resistance gene profiles were found in the 17 ST405 isolates (23%) causing sporadic cases of infection, but all of the resistance gene profiles differed in the 7 ST11 isolates (100%) (Figure 2). Two blaOXA-48-like genes (blaOXA-48 and blaOXA-245) were detected in different isolates within ST11-associated Outbreak B (H8; Table S1) and because the resistance phenotype profiles are identical for both of these OXA genes, these variants would not have been detected without sequencing (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of multidrug resistance loci in K. pneumoniae expressing blaOXA-48-like genes in relation to phylogeny. The name of each strain includes a letter representative of the epidemiological state [A, B, B2 and C for strains isolated in an outbreak and sporadic infection (SI) for isolated cases], hospital of isolation (H1–H9) and carbapenemase expressed. Genes conferring drug resistance are shown at the top. A heat map showing the presence of the gene (black/grey) and absence (white) is shown underneath. For topoisomerases encoded by gyrA and parC, the presence of mutations in the QRDR of each gene is shown in black/grey and the absence is shown in white. The asterisk indicates that all strains harbour blaOXA-245 and only one isolate harbours blaOXA-244 (SI_H8_OXA-244; Table S1).

The frequency of various resistance genes was determined for a selection of isolates that included only one representative isolate per outbreak, but all isolates causing sporadic cases (Figure S2); in total, the resistome of 49 isolates was analysed. Forty-two isolates (86%) carried blaOXA-48, 6 isolates (12%) carried blaOXA-245 and 1 isolate (2%) carried blaOXA-244; blaOXA-48 variants were detected only in ST11 isolates. Other β-lactamases without carbapenemase activity were also identified: 45 isolates (92%) carried a group 1 CTX-M ESBL, with blaCTX-M-15 being the most common, whereas 37 (76%) carried blaOXA-1, 35 carried (71%) blaTEM-1 and plasmid-encoded AmpC genes (blaCMY-2 and blaDHA-1) were identified in 2 isolates. The predominant genes encoding aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes were aac(6′)-Ib-cr (77%) and aac(3′)-II (67%); sul2 was the most common sulphonamide resistance gene in 69% of the isolates.

With respect to quinolone resistance, 47% of the isolates carried mutations in the QRDRs of both gyrA and parC, all ST11 isolates had mutations in both topoisomerases and only one ST405 isolate carried mutations, just in gyrA (Figure 2), 75% of isolates carried the plasmid-borne qnrB gene and 77% the aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes aac(6′)-Ib-cr; the presence of all of these genes together with the high prevalence of OqxAB efflux pumps among the isolates could contribute significantly to the reduced quinolone susceptibility of carbapenemase-producing isolates, as has been reported in the literature.51,52

In summary, WGS indicated that K. pneumoniae expressing blaOXA-48-like genes also carry a large number of accessory resistance genes (average, 14; range, 5–19). The most common mechanisms of resistance in addition to blaOXA-48-like expression were resistance to β-lactams, aminoglycosides and sulphonamides. ST11 isolates causing sporadic infections presented a much more diverse repertoire of resistance genes than sporadic infection-causing ST405 isolates.

Characterization of the IncL/M plasmid sequence encoding blaOXA-48-like genes

The blaOXA-48 gene has been reported to be located on an IncL/M plasmid, some sequences of plasmids of this type have been reported (K. pneumoniae plasmid pOXA-48 NC_019154.1).53 An IncL/M plasmid was detected in 94 of our isolates, with an average size of 64 000 bp and a structure similar to pOXA-48 (NC_019154.1) but harbouring blaOXA-48, blaOXA-245 or blaOXA-244 (Figure S3). This plasmid was detected in isolates belonging to ST405, ST11, ST437, ST15, ST16, ST846 and ST392, confirming its previously reported widespread distribution.54 Recently, a comparative analysis of plasmid genomes of fully sequenced IncL/M revealed two distinct genetic lineages (IncL and IncM), this new analysis assigns pOXA-48 (NC_019154.1) and its relatives to the IncL group, this may suggest that the IncL/M plasmids detected in our isolates could be eventually redefined as belonging to the IncL type.55

In three isolates, the IncL/M plasmid carried both blaOXA-48 and blaCTX-M-15; in two of these three isolates, blaCTX-M-15 was located in a Tn1999.4 similar to that described in the literature.56 In the remaining isolate, blaCTX-M-15 was located in a 3059 bp transposon containing ISEcp1, blaCTX-M-15 and a truncated Tn2-type transposase; this structure was located upstream of the rmoA gene in a region close to the end of the tra operon (Figure S4). A similar structure was described in the isolates associated with the first Australian outbreak due to blaOXA-48-expressing K. pneumoniae, although blaCTX-M-14 was detected instead of blaCTX-M-15.57 In order to determine the sequence variation within the plasmids, we determined SNPs with reference to the plasmid sequence (K. pneumoniae plasmid pOXA-48 NC_019154.1) and a pairwise comparison was calculated. IncL/M plasmids differed from each other by two SNPs on average (range, 0–7); if SNPs located in blaOXA-48-like genes were excluded, this average would be reduced to one SNP (range, 0–5), suggesting that highly preserved conserved IncL/M plasmids may be moving among all the isolates analysed regardless of their epidemiological links. Distinguishing between plasmids based on high-resolution SNP typing has been used to analyse other plasmids belonging to other incompatibility groups.58

In summary, closely related IncL/M plasmids were shared among all the studied isolates, among those causing either nosocomial outbreaks or sporadic cases, irrespective of whether they belonged to the same or a different multilocus ST, suggesting the continuous mobilization of the same plasmid among K. pneumoniae isolates carrying blaOXA-48-like genes.

Concluding remarks

Here, we report WGS and phylogenetic analysis of two K. pneumoniae STs (ST11 and ST405) expressing blaOXA-48-like genes and genetic mobile elements harbouring carbapenemase resistance genes isolated across Spain. We illustrate the utility of WGS for obtaining insights into the molecular epidemiology of disease-causing isolates by: (i) providing a high-resolution view in comparison with classical methodologies, mainly in persistent nosocomial outbreaks; (ii) demonstrating interhospital and inter-regional clone and plasmid spread among both emergent clones (ST11 and ST405); (iii) reconstructing the structure of IncL/M plasmids that harbour blaOXA-48-like genes; (iv) analysing the homology of these plasmids in a large strain collection; and (v) characterizing the distribution of a large number of resistance genes, which demonstrates good correlation between the phenotypic and genetic resistance profiles.

Funding

This study was supported by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (BA12/00022) and Subdirección General de Redes y Centros de Investigación Cooperativa, Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, the Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI RD12/0015), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (grant number PI12/01242) and Wellcome Trust UK (grant no. 098051).

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Supplementary data

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the excellent technical assistance provided by David Saez, Veronica Bautista, Sara Fernández Romero and Noelia Lara. We would like to thank the following collaborators for strain submissions: Esteban Aznar and Carolina Campelo (Lab. BrSalud, Madrid, Spain), Luisa García-Picazo (Hospital El Escorial, Madrid, Spain), Gloria Trujillo (Hospital San Joan de Deu, Fundació Althaia, Manresa, Barcelona, Spain), Isabel Sanchez-Romero (Hospital Puerta de Hierro, Majadahonda, Madrid, Spain), Ana Fleites (Hospital Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Spain), Alberto Delgado-Iribarren (Fundación Hospital de Alcorcón, Alcorcón Madrid, Spain), Mª Dolores Miguel (Hospital Cabueñes, Gijón, Spain), Emilia Cercenado (Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain) and Concepción Baladón (Laboratory of Dr Echevarne). We would like to thank the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute for providing bioinformatics support.

References

- 1.Lockhart SR, Abramson MA, Beekmann SE et al. Antimicrobial resistance among gram-negative bacilli causing infections in intensive care unit patients in the United States between 1993 and 2004. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45: 3352–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundmann H, Livermore DM, Giske CG et al. Carbapenem-non-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae in Europe: conclusions from a meeting of national experts. Euro Surveill 2010; 15: pii=19711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poirel L, Héritier C, Tolün V et al. Emergence of oxacillinase-mediated resistance to imipenem in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2004; 48: 15–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goren MG, Chmelnitsky I, Carmeli Y et al. Plasmid-encoded OXA-48 carbapenemase in Escherichia coli from Israel. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011; 66: 672–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfeifer Y, Schlatterer K, Engelmann E et al. Emergence of OXA-48-type carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in German hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56: 2125–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gülmez D, Woodford N, Palepou MF et al. Carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Turkey with OXA-48-like carbapenemases and outer membrane protein loss. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2008; 31: 523–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimou V, Dhanji H, Pike R et al. Characterization of Enterobacteriaceae producing OXA-48-like carbapenemases in the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012; 67: 1660–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oteo J, Hernández JM, Espasa M et al. Emergence of OXA-48-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and the novel carbapenemases OXA-244 and OXA-245 in Spain. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68: 317–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cantón R, Akóva M, Carmeli Y et al. Rapid evolution and spread of carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18: 413–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lascols C, Peirano G, Hackel M et al. Surveillance and molecular epidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates that produce carbapenemases: first report of OXA-48-like enzymes in North America. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57: 130–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis C, Chung C, Tijet N et al. OXA-48-like carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Ottawa, Canada. Diag Microbiol Infect Dis 2013; 76: 399–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pitart C, Solé M, Roca I et al. First outbreak of a plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolyzing OXA-48 β-lactamase in Klebsiella pneumoniae in Spain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55: 4398–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oteo J, Saez D, Bautista V et al. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Spain in 2012. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57: 6344–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galan-Sanchez F, Ruiz Del Castillo B, Marin-Casanova P et al. Characterization of blaOXA-48 in Enterobacter cloacae clinical strains in southern Spain. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2012; 30: 584–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torres E, López-Cerero L, Del Toro MD et al. First detection and characterization of an OXA-48-producing Enterobacter aerogenes isolate. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2014; 30: 584–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paño-Pardo JR, Ruiz-Carrascoso G, Navarro-San Francisco C et al. Infections caused by OXA-48-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a tertiary hospital in Spain in the setting of a prolonged, hospital-wide outbreak. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68: 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castanheira M, Deshpande LM, Mathai D et al. Early dissemination of NDM-1 and OXA-181-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Indian hospitals: report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program, 2006–2007. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55: 1274–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdelaziz MO, Bonura C, Aleo A et al. OXA-163-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Cairo, Egypt, in 2009 and 2010. J Clin Microbiol 2012; 50: 2489–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potron A, Nordmann P, Poirel L. Characterization of OXA-204, a carbapenems-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamase from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57: 633–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oteo J, Ortega A, Bartolomé R et al. Prospective multicenter study of carbapenemase producing Enterobacteriaceae from 83 hospitals in Spain: high in vitro susceptibility to colistin and meropenem. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59: 3406–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parkhill J, Wren BW. Bacterial epidemiology and biology—lessons from genome sequencing. Genome Biol 2011; 12: 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Köser CU, Holden MTG, Ellington MJ et al. Rapid whole-genome sequencing for investigation of a neonatal MRSA outbreak. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 2267–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris SR, Feil EJ, Holden MT et al. Evolution of MRSA during hospital transmission and intercontinental spread. Science 2010; 327: 469–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bentley DR, Balasubramanian S, Swerdlow HP et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature 2008; 456: 53–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu KM, Li LH, Yan JJ et al. Genome sequencing and comparative analysis of Klebsiella pneumoniae NTUH-K2044, a strain causing liver abscess and meningitis. J Bacteriol 2009; 191: 4492–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bose M, Barber R. Prophage Finder: a prophage loci prediction tool for prokaryotic genome sequences. In Silico Biol 2006; 6: 223–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Croucher NJ, Page AJ, Connor TR et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Research 2014; 43: e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Croucher NJ, Harris SR, Fraser C et al. Rapid pneumococcal evolution in response to clinical interventions. Science 2011; 331: 430–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 2006; 22: 2688–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drummond AJ, Rambaut A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol Biol 2007; 7: 214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drummond AJ, Rambaut A, Shapiro B et al. Bayesian coalescent inference of past population dynamics from molecular sequences. Mol Biol Evol 2005; 22: 1185–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drummond AJ, Ho SY, Phillips MJ et al. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLoS Biol 2006; 4: e88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012; 67: 2640–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mather AE, Reid SW, Maskell DJ et al. Distinguishable epidemics of multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium DT104 in different hosts. Science 2013; 341: 1514–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galtier N, Gouy M, Gautier C. SEAVIEW and PHYLO_WIN: two graphic tools for sequence alignment and molecular phylogeny. Comput Appl Biosci 1996; 12: 543–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 2004; 32: 1792–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res 2008; 18: 821–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carver TJ, Rutherford KM, Berriman M et al. ACT: the Artemis Comparison Tool. Bioinformatics 2005; 21: 3422–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Assefa S, Keane TM, Otto TD et al. ABACAS: algorithm-based automatic contiguation of assembled sequences. Bioinformatics 2009; 25: 1968–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berriman M, Rutherford K. Viewing and annotating sequence data with Artemis. Brief Bioinform 2003; 4: 124–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deleo FR, Chen L, Porcella SF et al. Molecular dissection of the evolution of carbapenem-resistant multilocus sequence type 258 Klebsiella pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: 4988–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung The H, Karkey A, Pham Thanh D et al. A high-resolution genomic analysis of multidrug-resistant hospital outbreaks of Klebsiella pneumoniae. EMBO Mol Med 2015; 7: 227–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.López-Camacho E, Rentero Z, Ruiz-Carrascoso G et al. Design of clone-specific probes from genome sequences for rapid PCR-typing of outbreak pathogens. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014; 20: O891–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grundmann H, Aanensen DM, van den Wijngaard CC et al. Geographic distribution of Staphylococcus aureus causing invasive infections in Europe: a molecular-epidemiological analysis. PLoS Med 2010; 7: e1000215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Albiger B, Glasner C, Struelens MJ et al. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Europe: assessment by national experts from 38 countries, May 2015. Euro Surveill 2015; 20: pii=30062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okoro CK, Kingsley RA, Connor TR et al. Intracontinental spread of human invasive Salmonella Typhimurium pathovariants in sub-Saharan Africa. Nat Genet 2012; 44: 1215–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woodford N, Turton JF, Livermore DM. Multiresistant Gram-negative bacteria: the role of high-risk clones in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2011; 35: 736–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Damjanova I, Tóth Á, Pászti J et al. Expansion and countrywide dissemination of ST11, ST15 and ST14 ciprofloxacin-resistant CTX-M-15-type β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae epidemic clones in Hungary in 2005—the new ‘MRSAs’? J Antimicrob Chemother 2008; 62: 978–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuan J, Xu X, Guo Q et al. Prevalence of the oqxAB gene complex in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli clinical isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012; 67: 1655–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bialek-Davenet S, Lavigne JP, Guyot K et al. Differential contribution of AcrAB and OqxAB efflux pumps to multidrug resistance and virulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015; 70: 81–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodríguez-Martínez JM, Díaz de Alba P, Briales A et al. Contribution of OqxAB efflux pumps to quinolone resistance in extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68: 68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andres P, Lucero C, Soler-Bistué A et al. Differential distribution of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes in clinical enterobacteria with unusual phenotypes of quinolone susceptibility from Argentina. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57: 2467–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poirel L, Bonnin RA, Nordmann P. Genetic features of the widespread plasmid coding for the carbapenemase OXA-48. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56: 559–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Potron A, Poirel L, Rondinaud E et al. Intercontinental spread of OXA-48 β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae over a 11-year period, 2001 to 2011. Euro Surveill 2013; 18: pii=20549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carattoli A, Seiffert SN, Schwendener S et al. Differentiation of IncL and IncM plasmids associated with the spread of clinically relevant antimicrobial resistance. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0123063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Proton A, Nordmann P, Rondinaud E et al. A mosaic transposon encoding OXA-48 and CTX-M-15: towards pan-resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68: 476–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Espedido BA, Steen JA, Ziochos H et al. Whole genome sequence analysis of the first Australian OXA-48-producing outbreak-associated Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates: the resistome and in vivo evolution. PLoS One 2013; 8: e59920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hazen TH, Zhao L, Boutin MA et al. Comparative genomics of an IncA/C multidrug resistance plasmid from Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species isolated from ICU patients: the utility of whole genome sequencing in healthcare settings. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 4814–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.