Abstract

The growing homebound population has many complex biomedical and psychosocial needs and requires a team based approach to care (Smith, Ornstein, Soriano, Muller, & Boal, 2006). The [XX] Visiting Doctors Program (MSVD), a large interdisciplinary home based primary care program in [XX], has a vibrant social work program that is integrated into the routine care of homebound patients. We describe the assessment process used by MSVD social workers, highlight examples of successful social work care, and discuss why social workers’ individualized care plans are essential for keeping patients with chronic illness living safely in the community. Despite barriers to widespread implementation, such social work involvement within similar home based clinical programs is essential in the interdisciplinary care of our most needy patients.

Keywords: Chronic illness, geriatrics, psychosocial intervention, social work, homebound, home based primary care

Introduction

As the population ages, the number of individuals living with multiple chronic illness and functional disability will continue to grow. For the over 2 million homebound elders living in the community, barriers to receiving necessary care in the community are significant (American Academy of Home Care Physicians, 2013). Medicare defines being homebound as the ability to leave home only with great difficulty and for absences that are infrequent or of short duration (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2013). Compared to their non-home bound counterparts, the homebound have a disproportionately high disease burden, significant functional limitations, and higher mortality (Cohen-Mansfield, Shmotkin, & Hazan, 2010; Kellogg & Brickner, 2000; Qiu et al., 2010). In addition, homebound individuals often require more complex care that addresses not only the medical needs of the chronically ill, but also the psychosocial needs of one isolated from typical social interactions and services (Kellogg & Brickner, 2000). Innovative models of care are needed to address the complex and unique needs of the homebound.

[XX] Visiting Doctors Program (MSVD) is a home based primary care practice in [XX] that provides care to an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse homebound population (K. Ornstein, Hernandez, DeCherrie, & Soriano, 2011; Smith et al., 2006). What started as a small pilot project in [XX] in 1995 has grown into the largest academic home based primary care program in the U.S. and currently cares for more than 1000 homebound individuals across [XX] each year. Patients in the program suffer from a wide variety of chronic illness and enter the program with significant symptom burden (Wajnberg, Ornstein, Zhang, Smith, & Soriano, 2013) as well as significant unmet biomedical and psychosocial needs (Katherine Ornstein, Smith, & Boal, 2009) and high levels of caregiver burden (Reckrey, Decherrie, Kelley, & Ornstein, 2013). In order to safely stay at home, these patients need significant support from the entire MSVD team including physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, administrative support, and social workers.

We believe that the contribution of social workers to the care of patients enrolled at MSVD is integral to the overall success of the program. This manuscript seeks to describe the social work program at MSVD in the context of social work in other community based medical settings and highlight the unique ways that social work is essential in the care of the homebound. We describe the evolution of the social work program at MSVD, the social work assessments developed by the program, and the wide range of clinical activities performed by MSVD social workers. We believe that this will add to the growing literature about the important role that social work plays in caring for patients with complex chronic illness and serve as a model for other practices seeking to integrate social work services into the care of their frail homebound patients. This is particularly important as demonstration projects such as the Independence at Home Act use shared savings models to incentivize providers to provide cost-effective care for frail, medically complex patients at home (Center For Medicare And Medicaid Innovation, 2012; Hayashi & Leff, 2012).

Background: Medical Social Work in the Community

Social workers have long helped meet the health related needs of the chronically ill living in the community. Social workers provided outreach for the medical practices at Massachusetts General Hospital in the early 1900s, were an important part of maternal and child health programs during the Great Depression, and have been an important part of Community Health Centers since the 1960s (Cowles, 2003). Yet today only 13% of social workers report working in the health care field. A minority of these social workers provide care for chronically ill patients in the community: only 44% of social workers in the health care field work outside the hospital, only 9% self identify as working in the field of aging, and only 1.3% are employed by home health agencies (National Association of Social Workers, 2006). While both the social work and medical communities support the idea of integrating social work into community-based medical care (Cowles, 2003), the role of social workers in community medical settings remains poorly defined.

Yet despite the low proportion of social workers working with chronically ill patients in the community, the rationale for social work involvement in medical services is straightforward: as Volland writes, “People who seek medical treatment still need guidance beyond the actual identification and treatment of a medical problem.” (Volland, 1996) Social workers can help identify unmet needs in patients with complex chronic illness and assist them in navigating the complex healthcare system and attaining optimal levels of functioning. As growing attention is being paid to the important ways that care coordination and team based care can improve the quality of care for patients in the community (Grumbach & Bodenheimer, 2004; Institute of Medicine, 2008; Saba, Villela, Chen, Hammer, & Bodenheimer, 2012), support for further social work involvement in community based medical settings will likely grow as well.

While the homebound exemplify the complex patients most in need of social work involvement in their routine medical care, this is not the standard of care among the diverse practices and programs providing care to the homebound. Physicians in private practice may independently perform house calls for a subset of the patients they care for. Concierge medicine practices, where an annual fee is paid to cover the costs of enhanced physician services, may offer home based primary care. Yet these models of care rarely employ a multidisciplinary team that includes social workers and instead providers refer to community based services as needed (DeCherrie, Soriano, & Hayashi, 2012). While multidisciplinary teams are more common in academic and Veterans Affairs home based primary care programs, the structure of these teams is highly variable (DeCherrie et al., 2012; Hayashi & Leff, 2012). While physicians may provide direct patient care, they may also function in a supervisory role while other providers such as nurse practicioners and nurses provide the bulk of direct patient care. Home care nurses, therapists, and social workers may be directly employed by the program or may work for independent agencies that provide services by referral. To our knowledge, there is no literature that specifically addresses the role of social work in the primary medical care of homebound adults such as those in MSVD.

Yet the homebound have much in common with other community-dwelling populations where social involvement is more routinely described. We identified three models of social work involvement in community-based medical settings that demonstrate the important role of social workers in the care of individuals with complex chronic illness and we believe that these models can inform the integration of social work into home based primary care programs: 1) disease-specific outpatient care, e.g., dialysis 2) mental health provision in a primary care, and 3) outpatient palliative care. An overview of how social workers positively impacted patient care in these models provides an important context to better understand the possible roles of social work in home based primary care.

First, social work has been an important part of the interdisciplinary care of individuals receiving dialysis since 1976 when Medicare mandated dialysis clinics to employ social workers in order to help address the complex psychosocial needs arising from end stage kidney disease (Beder, 2008). Subsequent studies have documented multiple benefits from social work interventions in the care of dialysis patients including improved adjustment to dialysis and lower levels of depression (Beder, 1999) as well as improved quality of life (Beder, 2008). Similar benefits were noted for community dwelling patients recovering from stroke: social-work led biopsychosocial interventions improved quality of life, depressive symptoms, cognitive function, social engagement, and adherence to the care plan (Claiborne, 2006).

Second, social workers are often part of teams that provide treatment for depression and anxiety in community based medical settings (Archer et al., 2012). Several models of care attempt to bring these social work led mental health services into the home. For example, a social work led program of modified problem solving therapy delivered in the home significantly reduced depressive symptoms and improved health status in chronically ill elders with depressive symptoms (Ciechanowski et al., 2004). Social work led problem solving therapy has also successfully improved depression in elders with cardiovascular disease (Gellis & Bruce, 2010). Such interventions reaffirm the role of social workers in addressing mental health symptoms in primary care.

Finally, palliative care focuses on “providing patients with relief from the symptoms, pain, and stress of a serious illness”(Center to Advance Palliative Care, 2012). Palliative care social workers assist with assessment, counseling, liaison with local resources and agencies, training and development activities, staff support, and clarification of healthcare wishes and values (Brandsen, 2005; Monroe, 1994). Multiple published case studies describe the unique ways social workers can address the psychosocial needs of those living with serious illness. Such examples include a social worker helping to secure hospice services for an undocumented immigrant dying of cancer (Parrish et al., 2012), a social worker arranging for a seriously ill patient to return to his home hundreds of miles away (Creal, 2013), and a social worker facilitating a family reconciliation despite complicated family dynamics (Baker, 2005).

Background: MSVD Patients

MSVD cares for a diverse patient population with a high illness burden. According to a recent study of MSVD between 2008 and 2010 (Wajnberg et al., 2013) 75% of patients were women and nearly 70% were over the age of 80. Thirty six percent were white, 32% were Hispanic, and 22% were black. Forty three percent had Medicaid and 32% lived alone. Ninety one percent required assistance with at least one ADL and 99% required assistance with at least one IADL. Chronic diseases were highly prevalent with 49% of patients with dementia, 26% with depression, 18% with chronic lung disease, and 13% with cancer. Forty three percent reported severe symptom burden (Wajnberg et al., 2013).

Importantly, MSVD patients also have well documented unmet needs beyond those related to disease symptoms. A study of a subset of patients enrolled at MSVD in 2001 and 2002 indicated that at program enrollment, the following unmet needs were reported: 53% with homecare-related needs, 41% with needs related to daily chores, 38% with financial needs, 39% with housing-related needs, and 27% with transportation needs (Katherine Ornstein et al., 2009). In addition, levels of burden among caregivers were high as compared to reported values from other populations such as elders with dementia. Burden was highest among caregivers who spent over 40 hours a week providing care and those who helped with a greater number of activities of daily living (Reckrey et al., 2013).

Social Work at MSVD

The role of social workers at MSVD has expanded significantly since the program’s inception in 1995 and social work is now an integral part of the MSVD program. The first social worker joined the MVSD program in 2001 as part of a grant funded initiative whose narrow focus was reducing burden of family caregivers and coordinating patient care within the hospital. Further grant funding and private donations allowed MSVD to expand their social work services and in 2004, the [XX] Hospital created a permanently funded social work salary line for MSVD. Social workers soon became more involved in the ongoing management of patient’s complex psychosocial needs and a social work supervisor position was created in 2006. The social work supervisor is part of the MSVD executive committee and contributes to the development of the program’s overall goals and direction. In addition to the hospital funded social worker, foundation and private donors have continued to support the social work program and the program has grown to three full time social workers and one social work coordinator. This means that there is currently one full time social worker for every 2 full time medical providers. In addition, one social worker hired though [XX] Hospital’s Accountable Care Organization works exclusively with MSVD as a care coordinator.

For the majority of patients, social workers become involved in the care of MSVD patients when primary care doctors place a referral to social work using an Electronic Medical Record (EMR) based messaging system to request social work assistance with a specific patient care issue. A review of the reasons for referral to social work at MSVD between July 2005 and February 2008 extracted from the EMR revealed that the most common reasons for referral to MSVD social work were obtaining adequate benefits and coordinating home care services (Table 1). Other reasons for referral included: connection with community resources, end of life issues, and assistance with patient and caregiver coping (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reasons for Referral to Social Work Program

| Reason for referral | Number of referrals | Percentage of referrals* |

|---|---|---|

| Securing benefits | 224 | 33% |

| Home care | 173 | 26% |

| Community resource referral | 68 | 10% |

| Caregiver coping issues | 68 | 10% |

| Housing | 45 | 7% |

| End of life issues | 39 | 6% |

| Abuse/neglect | 33 | 5% |

| Patient Coping Issues | 32 | 5% |

| Relationship issues | 23 | 3% |

| Other Issues** | 91 | 14% |

Percent totals >100 since more than one reason for referral can be given per case

Other issues include arranging care of pets, arranging cleaning of cluttered apartments, coordinating home based recreational services, assisting with moving apartments, etc.

In addition, social workers can respond directly to the requests of patient or families who call the practice requesting assistance with non-medical issues. Each social worker is assigned to work with a team of medical providers at MSVD. This facilitates close working relationships between social workers and medical providers. Social workers are encouraged to meet with providers on a regular basis to review patients with ongoing social work needs.

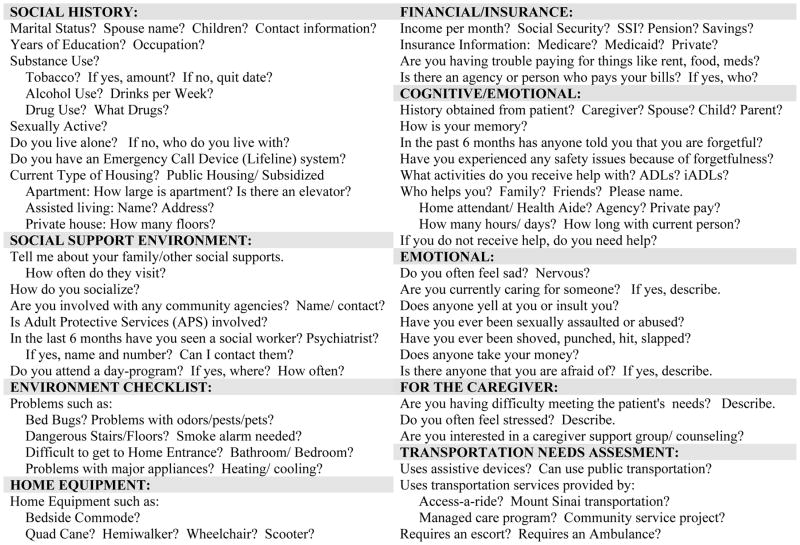

In order to facilitate the social workers’ patient assessment, a standardized social work initial assessment (Figure 1) was developed and integrated into the EMR. This assessment was designed to screen patients for a wide range of unmet needs as well as to document resources and support networks that patients already had in place. Importantly, the assessment template also includes space for the social worker’s narrative assessment of the patient. In this section, information obtained from the standardized questions is synthesized with the social worker’s own clinical impressions and a plan for intervention and follow-up is created.

Figure 1.

Initial Social Work Assessment

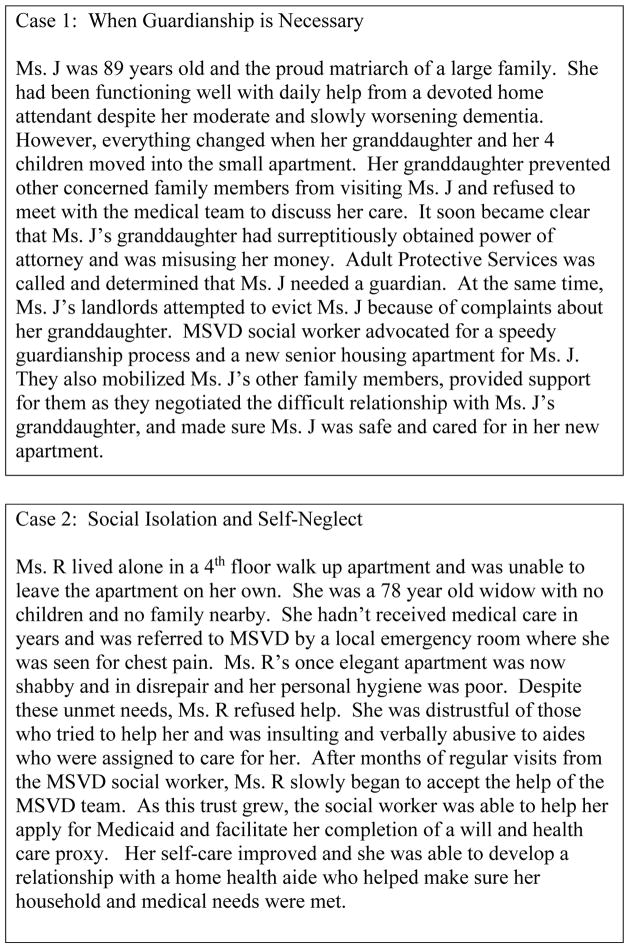

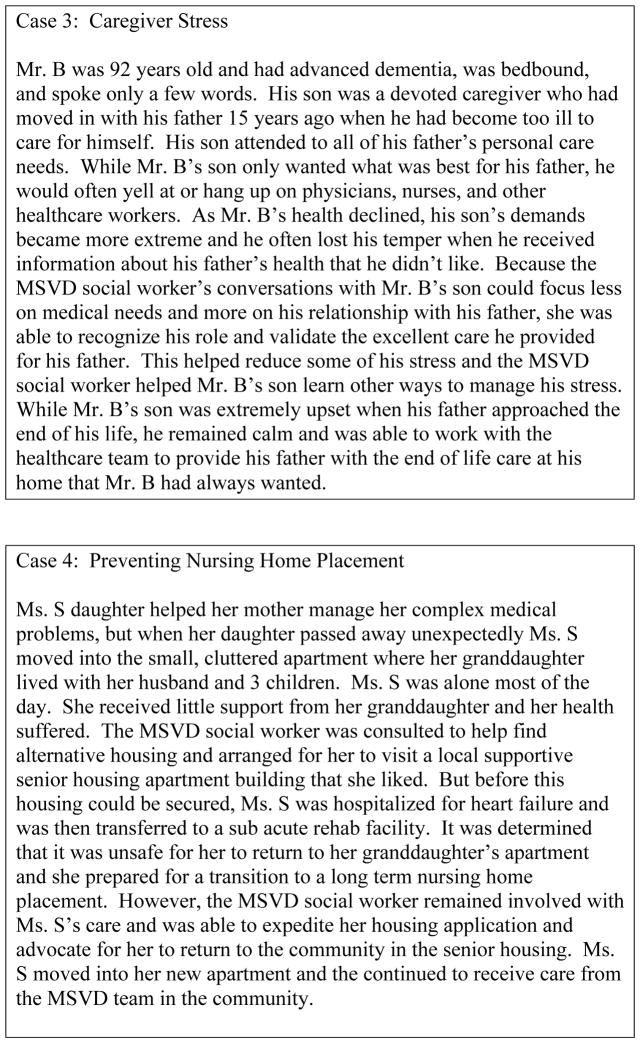

Social workers’ plans are tailored to meet patients’ individual needs and may include interventions such as home visits, frequent follow up phone calls to agencies and family members, one-on-one counseling for patients, visits to hospitalized patients, collaboration with and referral to community agencies, and establishing advance directives. The social worker may be involved with a patient only 1–2 times for acute interventions or as frequently as several times per week for more complicated issues. Social workers at MSVD have the opportunity to develop long-term relationships with the neediest patients and they remain available to patients and families throughout the time that patients are enrolled in MSVD. In order to help describe the wide range of social work interventions employed at MSVD, we have included 4 case studies (Figure 2) that provide concrete examples of these interventions and their impact on patient care.

Figure 2.

Social Work at MSVD

In addition to the direct clinical roles described above, social workers have many other roles at MSVD. Social workers are involved with the education of new staff as well as the education of medical students, residents, and fellows from the [XX] School of Medicine. Social work students are placed at MSVD for social work internships each year. The social work team oversees the semi-annual newsletter sent to all patients. Each month, social workers lead a staff meeting where the team reflects on patients who have died and the team writes condolence cards to their families. Social workers also organize an annual memorial service for patients who have died while being cared for by the MSVD program. Finally, the social work program has developed several of its own initiatives designed to address issues important to the practice. Such initiatives have included development of protocols to help patients eliminate infestations of bed bugs and targeted efforts to update all patients’ health care proxies.

Discussion

Social workers are an integral part of MSVD’s successful model of home based primary care and we believe that the experience of the MSVD social work team is useful for other programs that wish to integrate social worker services into the medical care of homebound patients. Social workers at MSVD have a wide variety of roles and many of these mirror the roles of social workers in other community based medical settings: they help patients cope with their complex chronic illness and proactively address problems that inhibit quality care, they provide counseling to help address depression and anxiety among patients and caregivers, and they support patients and families who are facing serious and often life-limiting illnesses. Yet because of the diverse needs of the homebound patients at MSVD, social workers provide comprehensive care that isn’t captured by any single one of these typical roles.

We believe that a key element to the success of the MSVD program is the social workers’ individualized approach to care for each patient. While case managers and other health care professionals are well equipped to meet many of the psychosocial needs of individuals with complex illness, social workers’ extensive training and broad scope of practice gives them a unique ability to both assess patients’ psychosocial needs and develop collaborative treatment plans. At MSVD we have found that this flexibility and creativity is what allows the program to honor each patient’s desire to remain safely in his or her home and we believe that this social work involvement should become the standard of care for home based primary care programs.

In the future we expect that the social work program at MSVD will supervise a growing number of social work interns. We also plan to expand social work led mental health services and to continue to build relationships with the rapidly changing array of community agencies and pilot programs that serve the homebound and those with complex chronic illness.

In order to support this growth, we understand that further research should address social work’s impact on patient centered outcomes and building a base of evidence to guide further social work interventions (Egan & Kadushin, 1999; Rosenfeld, Taylor, Liu, & Volland, 2008). However, because the MSVD program employs a team based approach to care it is difficult to tease out the impact of individual members of the care team. We have documented decreased unmet needs and decreased total caregiver burden among patients receiving home based primary care with MSVD (Katherine Ornstein et al., 2009) and believe that social workers play a key role in this. However, in the future we hope to refine our program assessments in order to more directly assess the impact of social workers at MSVD.

Successful incorporation of social workers into community based medical settings like MSVD can be challenging. Interdisciplinary collaboration, while considered positive for patients and providers, requires attention to team development and functioning and may be hindered by communication styles and personal characteristics (Abramson & Mizrahi, 1996). Yet with clarification of roles and clear articulation of team goals, social workers can be skilled liaisons with the community and help support patient’s participation in their own care (Jani, Tice, & Wiseman, 2012). At MSVD, we hold regular interdisciplinary biweekly team meetings to foster effective communication and interdisciplinary team building.

The most critical barrier to further incorporation of social workers in community based medical settings is the lack of direct reimbursement for medical social work services by insurers such as Medicare (Davitt & Gellis, 2011). This often leads to reliance on grants or private funds to initiate social work interventions and unfortunately such initiatives often dissolve when funding ends. In addition, this lack of reimbursement for social work services contributes to the perception that such services aren’t an integral part of medical care. However, we believe that as health care reforms seek to improve the quality of care while decreasing costs, development of innovative models of care will continue to grow and these models should prioritize increased social work involvement. The Independence at Home demonstration project is an example of how shared savings from cost-effective, home based care of frail elders can then be used to financially support the costs of a team based approach to care (Center For Medicare And Medicaid Innovation, 2012). Accountable Care Organizations and Patient Centered Medical Homes may provide further opportunities for funding of home based primary care programs that incorporate social work services into routine medical care (DeCherrie et al., 2012).

As the role of social workers in community based medical practices grows, continued evaluation of the role of social workers is needed. The complex biomedical and psychosocial needs of homebound patients are similar those of populations where social work involvement is routine, and we hope that the model of social work involvement at MSVD can serve as an example for those working to integrate comprehensive and individualized social work services in the medical care of their homebound patients.

References

- Abramson JS, Mizrahi T. When social workers and physicians collaborate: positive and negative interdisciplinary experiences. Soc Work. 1996;41(3):270–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Home Care Physicians. Public Policy Statement. 2013 Retrieved June 26, 2013, from http://www.aahcp.org/displaycommon.cfm?an=1&subarticlenbr=153.

- Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, Lovell K, Richards D, Gask L, … Coventry P. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006525.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M. Facilitating forgiveness and peaceful closure: the therapeutic value of psychosocial intervention in end-of-life care. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2005;1(4):83–95. doi: 10.1300/J457v01n03_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beder J. Evaluation research on the effectiveness of social work intervention on dialysis patients: the first three months. Soc Work Health Care. 1999;30(1):15–30. doi: 10.1300/j010v30n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beder J. Evaluation research on social work interventions: a study on the impact of social worker staffing. Soc Work Health Care. 2008;47(1):1–13. doi: 10.1080/00981380801970590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandsen CK. Social work and end-of-life care: reviewing the past and moving forward. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2005;1(2):45–70. doi: 10.1300/J457v01n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center For Medicare And Medicaid Innovation. Independence at Home Demonstration Fact Sheet August 2012. 2012 Retrieved September 2, 2012, from http://www.innovations.cms.gov/Files/fact-sheet/IAHfactsheet.pdf.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare and Home Health Care. 2013 Retrieved June 26, 2013, from http://www.medicare.gov/publications/pubs/pdf/10969.pdf.

- Center to Advance Palliative Care. 2012 Retrieved June 26, 2013, from https://getpalliativecare.org/whatis/

- Ciechanowski P, Wagner E, Schmaling K, Schwartz S, Williams B, Diehr P, … LoGerfo J. Community-integrated home-based depression treatment in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(13):1569–1577. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claiborne N. Effectiveness of a care coordination model for stroke survivors: a randomized study. Health Soc Work. 2006;31(2):87–96. doi: 10.1093/hsw/31.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Shmotkin D, Hazan H. The effect of homebound status on older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(12):2358–2362. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles LAF. Social Work in the Health Field: A Care Perspective. Routledge: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Creal L. Final journey--walking with Adam at end of life. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2013;9(1):4–6. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2012.758609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davitt JK, Gellis ZD. Integrating mental health parity for homebound older adults under the medicare home health care benefit. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2011;54(3):309–324. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2010.540075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCherrie LV, Soriano T, Hayashi J. Home-based primary care: a needed primary-care model for vulnerable populations. Mt Sinai J Med. 2012;79(4):425–432. doi: 10.1002/msj.21321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan M, Kadushin G. The social worker in the emerging field of home care: Professional activities and ethical concerns. Health Soc Work. 1999;24(1):43–55. doi: 10.1093/hsw/24.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellis ZD, Bruce ML. Problem solving therapy for subthreshold depression in home healthcare patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(6):464–474. doi: 10.1097/jgp.0b013e3181b21442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T. Can health care teams improve primary care practice? JAMA. 2004;291(10):1246–1251. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi J, Leff B. Medically Oriented HCBC: House Calls Make a Comeback. Generations. 2012;36(1):96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington D.C: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jani JS, Tice C, Wiseman R. Assessing an interdisciplinary health care model: the Governor’s Well mobile Program. Soc Work Health Care. 2012;51(5):441–456. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2012.660566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg FR, Brickner PW. Long-term home health care for the impoverished frail homebound aged: a twenty-seven-year experience. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(8):1002–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe B. Role of the social worker in palliative care. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(2):252–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Social Workers; NAoS Workers, editor Assuring the Sufficiency of a Frontline Workforce: A National Study of Licensed Social Workers. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ornstein K, Hernandez CR, DeCherrie LV, Soriano TA. The Mount Sinai (New York) Visiting Doctors Program: meeting the needs of the urban homebound population. Care Manag J. 2011;12(4):159–163. doi: 10.1891/1521-0987.12.4.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornstein K, Smith K, Boal J. Understanding and Improving the Burden and Unmet Needs of Informal Caregivers of Homebound Patients Enrolled in a Home-Based Primary Care Program. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2009;28(4):482–503. doi: 10.1177/0733464808329828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish M, Cardenas Y, Epperhart R, Hernandez J, Ruiz S, Russell L, … Thornberry K. Public hospital palliative social work: addressing patient cultural diversity and psychosocial needs. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2012;8(3):214–228. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2012.708113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu WQ, Dean M, Liu T, George L, Gann M, Cohen J, Bruce ML. Physical and mental health of homebound older adults: an overlooked population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(12):2423–2428. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reckrey JM, Decherrie LV, Kelley AS, Ornstein K. Health care utilization among homebound elders: does caregiver burden play a role? J Aging Health. 2013;25(6):1036–1049. doi: 10.1177/0898264313497509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld P, Taylor EA, Liu C, Volland PJ. Articulating the evidence base for effective social work practices: building a database to support a geriatric social work policy agenda. Soc Work Public Health. 2008;23(6):23–37. doi: 10.1080/19371910802059551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saba GW, Villela TJ, Chen E, Hammer H, Bodenheimer T. The myth of the lone physician: toward a collaborative alternative. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(2):169–173. doi: 10.1370/afm.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KL, Ornstein K, Soriano T, Muller D, Boal J. A multidisciplinary program for delivering primary care to the underserved urban homebound: looking back, moving forward. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(8):1283–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volland PJ. Social work practice in health care: looking to the future with a different lens. Soc Work Health Care. 1996;24(1–2):35–51. doi: 10.1300/J010v24n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wajnberg A, Ornstein K, Zhang M, Smith KL, Soriano T. Symptom burden in chronically ill homebound individuals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(1):126–131. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]