Abstract

Central nervous system (CNS) development is a finely tuned process that relies on multiple factors and intricate pathways to ensure proper neuronal differentiation, maturation, and connectivity. Disruption of this process can cause significant impairments in CNS functioning and lead to debilitating disorders that impact motor and language skills, behavior, and cognitive functioning. Recent studies focused on understanding the underlying cellular mechanisms of neurodevelopmental disorders have identified a crucial role for insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) in normal CNS development. Work in model systems has demonstrated rescue of pathophysiological and behavioral abnormalities when IGF-1 is administered, and several clinical studies have shown promise of efficacy in disorders of the CNS, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In this review, we explore the molecular pathways and downstream effects of IGF-1 and summarize the results of completed and ongoing pre-clinical and clinical trials using IGF-1 as a pharmacologic intervention in various CNS disorders. This aim of this review is to provide evidence for the potential of IGF-1 as a treatment for neurodevelopmental disorders and ASD.

Keywords: IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1, neurotrophic factors, central nervous system disorders, CNS development, neurodevelopmental disorders, ASD, autism spectrum disorder, Fragile X syndrome, Phelan-McDermid syndrome, Rett Syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Neurotrophic factors are critical for the proper development of the central nervous system (CNS) and play important roles in neuronal growth, survival, and migration. Disruption of these important developmental processes can lead to detrimental effects on overall brain functioning and result in debilitating CNS disorders. Neurotrophic factors have been the focus of recent research aimed at understanding the etiology and possible treatment for several neurodevelopmental and other CNS disorders. One such factor is Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1), a polypeptide containing 70 amino acids with a molecular weight of 7,649 Da (Rinderknecht & Humbel, 1978). IGF-1 belongs to a superfamily of related insulin-like hormones, which includes insulin, IGF-1, and IGF-2, all of which are similar in tertiary structure and primary amino acid sequence, but bind to different receptors to have different effects on development. Although IGF-1 is primarily produced in adults by the liver in response to growth hormone (GH) and affects a wide variety of cell types, its effect on early CNS development and neuronal plasticity suggests that IGF-1 acts as an endocrine, paracrine and autocrine hormone (Jones & Clemmons, 1995; Yakar et al., 1999). The ubiquitous nature of IGF-1 and its complex mechanisms of molecular expression, regulation and function has been the target of recent studies aimed at understanding and treating neurodevelopmental disorders.

IGF-1 Structure

GF-1 levels vary based on the stage of development and exhibit both spatial and temporal patterns of expression in CNS tissue. IGF-1 levels are low during the prenatal period (Sara & Hall, 1981) with IGF-1 mRNA detected as early as embryonic day 3 in chick embryos, when the neural tube starts to develop into distinct brain structures (Perez-Villamil, de la Rosa, Morales, & de Pablo, 1994), and embryonic day 16 in rodent brains, when synaptogenesis begins in the olfactory bulb (Ayer-le Lievre, Stahlbom, & Sara, 1991). IGF-1 mRNA is mainly expressed in cephalic regions during neurulation and in undifferentiated mesenchymal tissue during early stages of development, and is later found predominantly in neurons and glial cells (Bondy, 1991; de Pablo et al., 1993). Increased IGF-1 protein levels display a region-specific pattern coinciding with local neuronal cell proliferation, differentiation and synaptogenesis (Andersson et al., 1988; Bach, Shen-Orr, Lowe, Roberts, & LeRoith, 1991; J. Baker, Liu, Robertson, & Efstratiadis, 1993; Perez-Villamil et al., 1994). IGF-1 production in the CNS eventually decreases and by adulthood, is primarily expressed by hepatocytes in response to growth hormone (GH) (Jones & Clemmons, 1995).

In extracellular circulation, the majority of IGF-1 molecules bind to one of ten binding proteins (IGFBP) and to an acid-labile subunit (ALS) to form a ternary complex (Baxter, Martin, & Beniac, 1989). The IGF-1 binding proteins are produced by neurons, astroglial cells, cerebral blood vessels, and choroid plexus epithelia (Lee, Michels, & Bondy, 1993). Binding proteins have several functions, including 1) transportation of IGF-1 in plasma; 2) stabilization and prolongation of the half-life of IGF-1; 3) determination of tissue and cell-specific localization of IGF-1, and 4) modulation of IGF-1 interactions with its receptor (Firth & Baxter, 2002; Rinderknecht & Humbel, 1978). Of the ten IGFBPs produced in humans, only IGFBPs 1–6 have a high affinity for IGF-1 and only IGFBP-3 and IGFBP-5 demonstrate the structural domains necessary to bind ALS and form this ternary compound (Boisclair, Rhoads, Ueki, Wang, & Ooi, 2001; Hashimoto et al., 1997; Twigg & Baxter, 1998). The biological importance for the structural differences within the IGFBP group and the function of ALS are not completely understood, but are evidence of the diversity of IGF-1 action. The differences in IGFBP-specific proteases have also been found to cleave peptides from the IGFBP, reducing their affinity for IGF-1 and are thus important in regulating the tissue-specific biological functioning of IGF-1 (Maile & Holly, 1999).

While the majority of IGF-1 in adults is released by hepatocytes, low levels of IGF-1 expression continues in various parts of the brain, including the olfactory bulb, cerebral cortex, hypothalamus, brainstem and cerebellum (Bach et al., 1991). The production of IGF-1 in the adult CNS is localized to areas of ongoing differentiation and is disproportionately lower than the expression of IGF receptors in the brain, suggesting that IGF-1 can cross into the CNS from the periphery. Studies tracking exogenously administered IGF-1 into the brain have confirmed that peripheral IGF-1 can cross both the blood brain barrier and the blood-CSF barrier ((Bach et al., 1991; Pan & Kastin, 2000; Reinhardt & Bondy, 1994). The actions of IGF-1 in the CNS are not only location specific, but also dependent on its molecular structure. Once present in the serum, an acid protease cleaves the N-terminal region of IGF-1 to create two molecules: truncated IGF-1, referred to as des(1–3) IGF-1, and the cleaved glycyl-prolyl-glutamate peptide, referred to as GPE or (1–3)IGF-1 (Sara et al., 1993; Yamamoto & Murphy, 1994). It was initially thought that (1–3)IGF-1 was biologically inactive since it did not directly interact with IGF1R or appear to affect the des(1–3) IGF-1 binding affinity for IGF1R, and on its own did not promote neural growth. In 1989, however, Sara and colleagues observed that (1–3)IGF-1 binds to NMDA receptors to potentiate potassium evoked release of dopamine and acetylcholine (Sara et al., 1993). (1–3)IGF-1 was also shown to reduce cortical infarction in areas of the hippocampus after administration in rats with neuronal hypoxic-ischemic injuries (Guan, Waldvogel, Faull, Gluckman, & Williams, 1999). The various mechanisms of action by which IGF-1 crosses into the CNS and exerts its effect as either an intact molecule or cleaved tripeptide will be discussed in the section on clinical implications of IGF-1 as a therapeutic agent.

Mechanism of Action

In the CNS, IGF-1 exerts its actions by binding to its receptor (IGF1R), a membrane-bound glycoprotein composed of two α and two β subunits (Prager & Melmed, 1993; Rechler & Nissley, 1985). Once IGF-1 binds to IGF1R, the tyrosine kinase domains on the β subunits activate the PI3K/mTOR/AKT1 (phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase / mammalian target of rapamycin / serine-threonin-specific protein kinase AKT-PKB), and MAPK/ERK (mitogen-activated protein kinases / extracellular signal-regulated kinases) pathways to induce its downstream effects (Escott Jacobus, & Loss, 2013; “Fmr1 knockout mice: a model to study fragile X mental retardation. The Dutch-Belgian Fragile X Consortium,” 1994; Inoki, Li, Xu, & Guan, 2003; Kooijman, 2006; Xu, Cai, & Wu, 2012). The interactions between these pathways and their feedback loops are extensive and have been comprehensively reviewed elsewhere (Kooijman, 2006; Wymann & Pirola, 1998). However, the general effect of IGF-1 on these pathways will be discussed below and how this mechanism may lead to therapeutic activity is an important area of study and will be explained in the Discussion section.

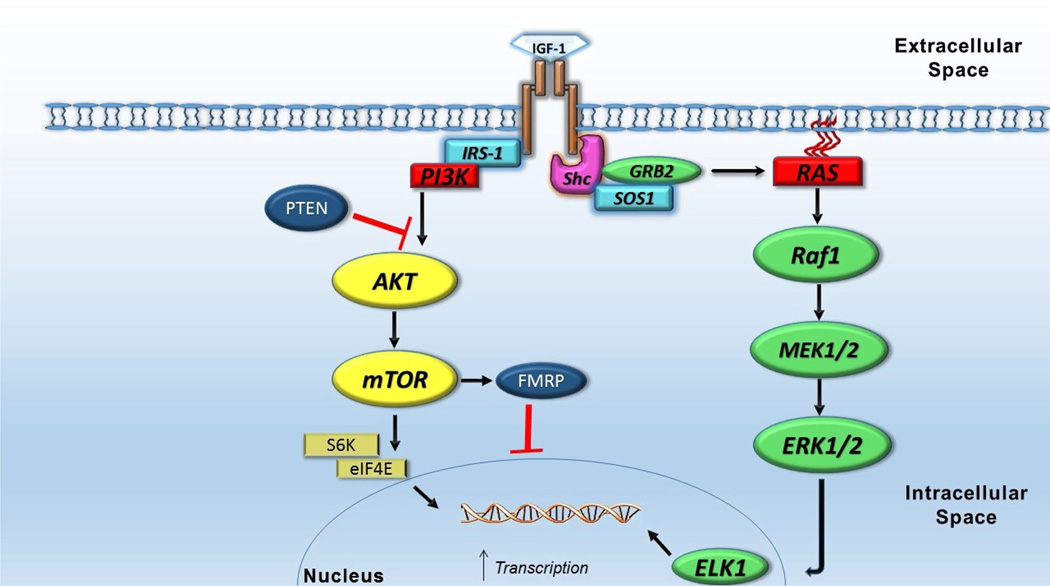

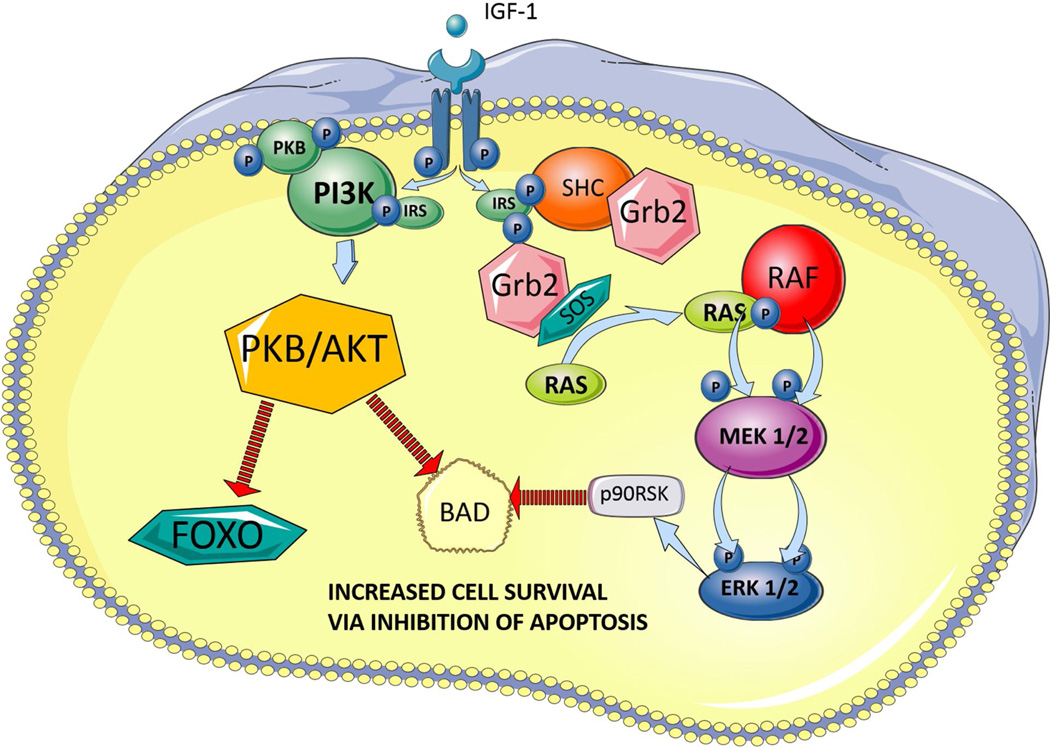

Activation of IGF1R causes recruitment of various molecules to activate the PI3K/mTOR and MAPK/ERK pathways. The PI3K/mTOR pathway recruits AKT1 to activate mTOR, which in turn initiates protein translation via down-stream effectors S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (EIF4EBP1) (Fingar & Blenis, 2004). By promoting protein translation via S6K1 and EIF4EBP1, the PI3K/mTOR pathway is important in regulating cell cycling/survival, gene expression, and cytoskeletal remodeling (Figure 1) (Kotani et al., 1994; McIlroy, Chen, Wjasow, Michaeli, & Backer, 1997; Wymann & Pirola, 1998). Phosphorylation of S6K1 not only improves ribosome and protein synthesis, but also inhibits apoptosis via phosphorylation of Bcl-2-associated agonist of cell death (BAD) (Bonni et al., 1999; Datta et al., 1997; Harada, Andersen, Mann, Terada, & Korsmeyer, 2001). AKT1 pathway activation also inhibits the Forkhead Box O (FOXO) apoptotic pathway (Stitt et al., 2004) and inactivates the pro-apoptotic c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway, which implicates a therapeutic role of IGF-1 in inhibiting premature cell death (Figure 2) (Aikin, Maysinger, & Rosenberg, 2004; Wang, Yang, Xia, & Feng, 2010). Other studies have shown that IGF-1 interferes with apoptosis independent of the PI3K/mTOR pathway, thus providing multiple paths for cell survival via activation of IGF1R (Galvan, Logvinova, Sperandio, Ichijo, & Bredesen, 2003). The MAPK/ERK pathway also plays an important role in gene expression, cell survival and differentiation. Activated by various polypeptide hormones, chemokines, and growth factors (including IGF-1), ERK targets nuclear transcription factors, which are important in inducing expression of genes that promote cell survival, division and motility (Clerk, Aggeli, Stathopoulou, & Sugden, 2006; Dhillon, Hagan, Rath, & Kolch, 2007; Geschwind, 2008; Pende et al., 2004). Although IGF-1 is a stronger activator of PI3K/mTOR than MAPK/ERK, several studies have shown significant cross-inhibition and activation between the two pathways, indicating that even if one pathway is disrupted, it may still be activated downstream via an alternate pathway (Clerk et al., 2006; Mendoza, Er, & Blenis, 2011).

Figure 1. IGF-1 downstream effects on transcription, protein synthesis and cell growth.

IGF-1 acts on its receptor to initiate several pathways responsible for protein translation, which in turn aids in cell growth, migration and differentiation. Activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway by IGF-1 leads to activation of S6 kinase proteins and phosphorylation of eIF4E, which in turn lead to increased mRNA translation (Hay & Sonenberg, 2004). IGF-1 also activates the MAPK pathway, which increases neuronal proliferation via ERK activation and increases gene transcription via ELK1 activation ((Fernandez & Torres-Aleman, 2012)

Abbreviations: IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IRS-1, insulin receptor substrate 1, PI3K., phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase; PTEN, phosphate and tensin homolog; Akt, serine/threonine-specific protein kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; FMRP, Fragile X mental retardation protein; S6K, P70-S6 kinase 1; eIF4E, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E; Shc, Src-homology and collagen homology; SOS1, son of sevenless homolog 1; GRB2, growth factor receptor-bound protein 2; Raf1, Rapidly accelerating fibrosarcoma kinase protein 1; MEK, MAPK/ERK kinase or mitogen-activated protein kinases/extracellular signal-regulated kinases; ELK1, ETS-domain protein Elk-1

Figure 2. IGF-1 mechanisms of inhibiting apoptosis.

IGF-1 receptor activation mediates cell survival via several pathways, including inhibition of apoptosis via three pathways shown below. Two converging pathways have the similar end result of blocking BAD induced cell death: 1) activation of PI3K/Akt pathway, which phosphotylates BAD to block apoptosis (Datta et al., 1997) and 2) activation of the MAP kinase pathways to phosphorylate BAD, thus blocking apoptosis (Bonni et al., 1999). The third pathway involves Akt inhibition of apoptosis signaling FOXO transcription factors (Stitt et al., 2004).

Abbreviations: IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IRS, insulin receptor substrate, PI3K., phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase; SHC, Src-homology and collagen homology; SOS, son of sevenless homolog; GRB2, growth factor receptor-bound protein 2; Raf, Rapidly accelerating fibrosarcoma kinase protein; MEK, MAPK/ERK kinase or mitogen-activated protein kinases/extracellular signal-regulated kinases; PKB/Akt, protein kinase B/serine/threonine kinase; BAD, Bcl-2 associated death promoter; FOXO, forkhead box O

The downstream effects of IGF-1 through the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/mTOR pathways were further explored in subsequent studies and it was discovered that IGF-1 does not produce all of its effect as an intact molecule (Corvin et al., 2012; Sara et al., 1993) . Corvin and colleagues (2012) studied the differences between recombinant human IGF-1 (rhIGF-1), an exogenously produced intact IGF-1 which has not yet been cleaved, and the tripeptide (1–3)IGF-1 by exposing neuronal cell cultures to either molecule, then using immunocytochemistry techniques to identify the pathways activated and the overall effect on cell growth. Although (1–3)IGF-1 did not directly bind to the IGF1R, it caused a significant increase in IGF1R activation (Corvin et al., 2012). This is explained by the concurrent increase in IGF-1 production when (1–3)IGF-1 is applied to cells, implying that (1–3)IGF-1 stimulates release of intact IGF-1, which in turn activates the IGF1R. When examining the pathways activated by these two molecules, the effects differed depending on cell type and dosage. In neurons, rhIGF-1 activates both PI3K and MAPK pathways, while (1–3)IGF-1 decreases MAPK pathway activation and has no effect on the PI3K pathway. In glial cells, rhIGF-1 has no effect on the PI3K pathway while (1–3)IGF-1 increased activation of PI3K. However, the downstream effect on synaptic markers of rhIGF-1 and (1–3)IGF-1 were very similar. Both molecules resulted in increased levels of important excitatory synaptic markers such as synapsin-1, a pre-synaptic marker responsible for regulating neurotransmitter release ((Hilfiker et al., 1999), and post-synaptic density protein-95 (PSD-95), a scaffolding protein responsible for proper synapse and receptor formation (Figure 3) (Kim & Sheng, 2004). Neither molecule changed the levels of gephyrin, a post-synaptic marker of inhibitory neurons (Corvin et al., 2012; Micheva, Busse, Weiler, O’Rourke, & Smith, 2010). The differences in targeted cells, pathway activation and interactions of intact IGF-1 and (1–3)IGF-1 are not yet completely understood, but are integral in maintaining balance between excitatory and inhibitory neural transmission in the CNS.

Figure 3. Pre- and post-synaptic markers influenced by IGF-1.

IGF-1 is important for the development and maintenance of mature synapses via influence on various synaptic markers. The presence of IGF-1 is necessary for proper levels of synapsin-1, a pre-synaptic protein that regulates neurotransmitter release (Hilfiker et al., 1999), and PSD-95, a post-synaptic scaffolding protein that aids in maintaining synaptic structure, as well as AMPA and NMDA receptor binding (Corvin et al., 2012; Kim & Sheng, 2004).

Abbreviations: CASK, calcium/calmodulin dependent serine protein kinase; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate; AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid; PSD-95; PDZ (1–3), post-synaptic density protein 95 – drosophila disc large tumor suppressor and zonula occludens-1 protein; SH3, SRC Homology 3 Domain; GK, glycerol kinase; GKAP, guanylate kinase-associated protein; TARP, TCR gamma alternate reading frame protein

Role in CNS Development

The importance of IGF-1 during development was established through observations that IGF-1 deficient mice developed structural brain abnormalities that varied in both location and cell types involved. For example, mice with null mutations in the IGF-1 gene had both somatic and brain growth retardation, fewer oligodendrocytes, less myelin in brain white matter, and dysfunctional synapse formation (J. Baker et al., 1993; Beck, Powell-Braxton, Widmer, Valverde, & Hefti, 1995; Cheng et al., 2003; Ye, Li, Richards, DiAugustine, & D’Ercole, 2002). Similarly, mice with defective IGF1R or IGFBP demonstrated decreased brain growth, fewer neurons, decreased neuronal proliferation, increased neuron apoptosis, fewer oligodendrocytes, decreased myelination and decreased spine formation (Divall et al., 2010; Gutierrez-Ospina, Calikoglu, Ye, & D’Ercole, 1996; Holzenberger et al., 2000; Liu, Baker, Perkins, Robertson, & Efstratiadis, 1993; Zeger et al., 2007). Specific areas of the brain are noted to be more sensitive to the effects of IGF-1 deficiency, including motor neurons, oligodendrocytes, cerebellar Purkinje and granulosa cells (Lewis et al., 1993; Riikonen, 2006; Torres-Aleman, Villalba, & Nieto-Bona, 1998).

The majority of initial studies aimed at studying the downstream effects of rhIGF-1 have used transgenic mice that had genetic alterations in the expression of IGF-1, IGF-1R, or IGF binding proteins. Arsenijevic and colleagues (1998) examined the ability of IGF-1 to increase the number of differentiated neurons and found that IGF-1 activation of IGF1R promotes differentiation of postmitotic neuronal precursors in vitro (Arsenijevic & Weiss, 1998). An in vivo study of IGF-1 and mitotic effect on cells showed that treatment of cultures with IGF-1 resulted in a two-fold increase in neurite-bearing cells after 48 hours and a five-fold increase after 15 days when compared with controls. IGF-1 treated cultures also promoted neuronal survival and enhanced morphological differentiation of hypothalamic neurons, demonstrating the potency of IGF-1 as a neurotrophic factor in the CNS (Torres-Aleman, Naftolin, & Robbins, 1990).

After establishing that IGF-1 has a significant effect on cell proliferation and neuronal differentiation, studies began to explore the influence of IGF-1 on cell cycle kinetics. Hodge et al. (2004) investigated in vivo effects of IGF-1 on proliferating neuroepithelial cells in transgenic mice that over-express IGF-1 in the brain. The results indicated that these transgenic mice have increased cell numbers in the cortical plate by embryonic day 16 as well as increased numbers of neurons and glia during development, which was a result of a reduction in the length of the G1 and total cell cycle, and a promotion of cell cycle reentry (Hodge, D’Ercole, & O’Kusky, 2004). In a similar experiment, Popken et al. (2004) not only demonstrated an increase in tissue volumes of the cerebral cortex (most notably the dentate gyrus, subcortical white matter, medial habenular nucleus and hippocampus) with IGF-1 in transgenic mice, but also a decrease in the density of apoptotic cells (Popken et al., 2004). Other studies in vivo began to focus on specific types of neuronal cells affected by IGF-1, such as oligodendrocytes. Although Mozell et al. (2004) had previously established that IGF-1 stimulates oligodendrocyte production in aggregate cultures treated with IGF-1, the in vivo effects were not studied until Ye et al. (1995) examined brain growth and myelination in transgenic mice that overexpress IGF-1 (Mozell & McMorris, 1988) (Ye, Carson, & D’Ercole, 1995). In this study, transgenic mice brains were examined grossly and using radioimmunoassays, which revealed not only a significant increase in brain size without changes in body size, but also an increase in myelin disproportionate to brain size, indicating an increased production of myelin per oligodendrocyte (Carson, Behringer, Brinster, & McMorris, 1993).

Another specific neural cell type studied by both in vitro and in vivo studies is the astrocyte, a subtype of glial cells. In general, glial cells are separated into two subtypes, macroglia and microglia, and are responsible for physical and physiologic support, immune regulation, repair, and maintenance of homeostasis in the CNS. Microglial cells are specialized macrophages that act as the immune system of the CNS by promoting inflammation (Kettenmann, Hanisch, Noda, & Verkhratsky, 2011). Astrocytes, a subtype of macroglia, provide physical and metabolic support, regulate cerebral blood flow, and repair injured neurons in the CNS (Volterra & Meldolesi, 2005). Recent research has focused on astrocyte involvement in the modulation of synaptic transmission, long-term potentiation, and proper development of the nervous system (Barker & Ullian, 2010).

Based on the observation that IGF-1 mRNA is transcribed in cultured rat astroglial cells, it was hypothesized that IGF-1 promotes astroglial growth and differentiation via paracrine or autocrine actions (Ballotti et al., 1987). This hypothesis was strengthened by the observation that adult transgenic mice that overexpress astrocyte-derived IGF-1 have 50–270% more glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a protein expressed by astrocytes (Ye et al., 2004). Cao et al. (2003) performed an in vivo study using hypoxic insults to near-term fetal sheep to explore glial cell responses to rhIGF-1 treatment. Their results were not only consistent with prior studies in demonstrating that rhIGF-1 treatment increases the density of myelin producing cells and decreases cell apoptosis, but also showed increases in the number of GFAP and isolectin B4 staining cells, both of which are specific to microglia and astrocyte cells (Cao et al., 2003).

Clinical Considerations

After crossing the BBB, IGF-1 has been shown to promote neuronal growth and development (Arsenijevic & Weiss, 1998; Hodge et al., 2004; Jorntell & Hansel, 2006; Torres-Aleman et al., 1990), leading it to be the focus of many clinical and preclinical studies aimed at understanding CNS development. However, IGF-1 transport into the CNS is not easily accomplished via passive diffusion given the size of the IGFBP-IGF-1 complex and the low lipid solubility of IGF-1 (Pardridge, 1997). By tracking the influx rate of exogenously administered labeled IGF-1 into the brain of mice (Pan & Kastin, 2000) or rats (Reinhardt & Bondy, 1994), it was confirmed that peripheral IGF-1 can cross from the blood into the brain parenchyma in order to cross into the CNS. Labeled IGF-1 was also transported into the brain after IGF-1 injection into the lateral ventricle, indicating that IGF-1 also crosses the blood-CSF barrier (Bach et al., 1991), a finding further supported by the presence of IGF-1 receptors in both the choroid plexus and the endothelial cells of brain capillaries (H. J. Frank, Pardridge, Morris, Rosenfeld, & Choi, 1986; Marks, Porte, & Baskin, 1991). The transport systems across the BBB and the blood-CSF barriers are not completely understood but have been shown to make use of both neurotrophic and neurovascular coupling mechanisms. These mechanisms require transport proteins and several biologic mediators to stimulate the activity of matrix metalloproteinase-9 to cleave IGF-1 from its binding protein, freeing it to become biologically active (Nishijima et al., 2010). The importance of this mechanism becomes apparent when considering the structure and route of administration of exogenous IGF-1 to act as an effective therapeutic agent. The mechanism of action by which IGF-1 crosses into the CNS and the differences between intact IGF-1 and its cleaved products became important when considering which aspect of the IGF-1 molecule should be used as a therapeutic agent. When administered intravenously, rhIGF-1 is quickly sequestered by binding proteins (F. J. Ballard et al., 1991), forming a complex that is too large to easily cross the BBB and can lead to acute hypoglycemic events (Firth, McDougall, McLachlan, & Baxter, 2002). The cleaved GPE, (1–3)IGF-1, has a very low affinity for IGFBPs and allows easier passage across the BBB via passive diffusion, but is also enzymatically unstable and its half-life after a single intravenous bolus is less than 2 minutes (Batchelor et al., 2003). The low affinity of (1–3)IGF-1 for IGFBPs also increases plasma clearance and is almost completely cleared from circulation within eight minutes of intraperitoneal injection, reducing influx rates into the brain (A. M. Baker et al., 2005). Direct administration into the CNS via intracerebroventricular (ICV) route results in a longer half-life of (1–3)IGF-1, but this route of administration has a higher risk of complications and is primarily reserved for animal models. Another complication of using (1–3)IGF-1 alone is that it is about 5 times more potent than intact IGF-1, resulting in an increase and prolongation of potential adverse events like hypoglycemia (Tomas et al., 1991; Walton, Dunshea, & Ballard, 1995). However, NNZ-2566, an analog of (1–3)IGF-1, has a longer half-life and is well tolerated, and is currently being studied in clinical trials in at least two neurodevelopmental disorders, Rett syndrome (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01703533) and Fragile X syndrome (FXS; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01894958). To improve the efficacy and efficiency of IGF-1, administration along with several cytokines that might use common intracellular signaling pathways were studied. One such cytokine is erythropoietin (EPO), which has overlapping functions with IGF-1 pathways and function in vivo to protect neurons from ischemic damage (Buemi et al., 2005; Fischer, Wiesnet, Marti, Renz, & Schaper, 2004; Ghezzi & Brines, 2004). Fletcher and colleagues (2009) found that combining EPO with rhIGF-1 led to a synergistic activation of the PI3K pathway to protect against apoptosis and hypothesized that co-administration would act as a protective factor against brain tissue damage and that intranasal administration was more effective than intravenous (Digicaylioglu, Garden, Timberlake, Fletcher, & Lipton, 2004; Fletcher et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2010). They found that intranasal administration of rhIGF-1 and EPO in mice was not only effective in treating hypoxic-ischemic brain injury, but also that intranasal administration was more efficient at crossing into the CNS than intravenous, subcutaneous or intraperitoneal administration (Fletcher et al., 2009). The specific mechanism underlying intranasal IGF-1 passage into the CSF is not well understood, but is thought to occur via intracellular transport along olfactory neurons, whose dendrites are directly exposed to the external environment in the nasal passage with axons projecting through the cribriform plate, or along the trigeminal nerve which ends close to the epithelial surface of the upper nasal passageway (Thorne, Pronk, Padmanabhan, & Frey, 2004). The varying effects of full length IGF-1 and (1–3)IGF-1 on peripheral and CNS tissues, along with the different mechanisms by which they are transported into the CNS, need to better understood in order to establish a well-tolerated protocol for IGF-1 structure, dosage and route of administration for future preclinical and clinical studies.

In children, low IGF-1 levels have been associated with reduced childhood growth, low body mass index and low childhood IQ [17, 49]. These abnormalities may lead to a variety of behavioral disturbances and CNS pathology, including deficient locomotor activity and learning deficits on memory tasks. Low IGF-1 concentrations in the CSF were also found in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Vanhala, Turpeinen, & Riikonen, 2001). In adults, low levels of circulating IGF-1 are correlated with slower mental processing speed and reduced executive functioning (Aleman et al., 1999; Papadakis et al., 1995) The IGF system is considered integral to brain development and additional studies focused on the continuing effects in adulthood. By measuring levels of IGF-1 mRNA in human brains, IGF-1 has been shown to have a significant effect on neuronal plasticity in specific parts of the brain that are most subject to continuous alterations in synapses, including the hippocampus and cerebellum (Jorntell & Hansel, 2006).

Given the established role of IGF-1 in neuronal differentiation and development, several specific CNS disease states became candidates for targeted therapy with rhIGF-1. One of the first indications to use rhIGF-1 as a therapeutic agent was growth failure. Mecasermin (brand name: Increlex, Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals) was developed as a synthetic analog of IGF-1 and approved for use in patients with short stature due to primary IGF-1 deficiency (Laron’s dwarfism) that did not respond to growth hormone (Rosenbloom, 2007). After it was discovered that rhIGF-1 administration was well tolerated and had beneficial effects on growth, possible therapeutic effects on other disorders linked to IGF-1 deficiency emerged. Because IGF-1 increases the number of oligodendrocytes and myelin production in the CNS, it was hypothesized to be of value in the treatment of demyelinating diseases, such as Multiple Sclerosis. And because IGF-1 is also involved in synaptogenesis, dendritic sprouting, and the protection of neuronal apoptosis, it may be relevant to diseases marked by neuronal degeneration, such as Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, Parkinson’s Disease, and dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Finally, treatment with rhIGF-1 has also been proposed in neurodevelopmental disorders where deficits in synaptic neurotransmission play an etiologic role, such as Phelan-McDermid syndrome (PMS) and Rett syndrome, both single gene causes of ASD. IGF-1 has been studied in these diseases in vivo and in vitro, using animal models systems, human neuronal models derived from induced pluripotent stem cells, and recently, human clinical trials.

The aim of this paper is to review preclinical and clinical trials of rhIGF-1 in CNS diseases and specifically to explore the clinical potential of rhIGF-1 in neurodevelopmental disorders.

METHODS

All randomized controlled clinical trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, and review papers were included in this review. The electronic search strategies used included MEDLINE and PUBMED for all years available. The phrases "IGF-1," "IGF-1 AND CNS," "IGF-1 AND development," "IGF-1 AND ALS," "IGF-1 AND autism," "IGF-1 AND multiple sclerosis," “IGF-1 AND parkinson’s disease," "IGF-1 AND alzheimer’s dementia," "IGF-1 AND mechanism of action," "IGF-1 AND binding proteins," "IGF-1 AND neurons," and "IGF-1 AND Rett syndrome" were used to search for relevant papers. It should be noted that both “IGF-1” and “insulin like growth factor 1” were used during the search as a few papers had not included “IGF-1” as a keyword. Also, some of the literature searches that included disease models were limited to only include clinical trials. After each relevant study was obtained as full texts, the authors included them in the review after thorough discussion of outcome measures, risks of bias, and heterogeneity in results. Each paper was then reviewed for relevant data supporting the implication of IGF-1 involvement in various CNS disorders. After review of multiple papers, several studies that were cited within articles found through the original search terms that were relevant to this topic were also reviewed and included. The studies included were in vitro and in vivo pre-clinical trials, as well as clinical trials in humans. Since studies on the basic science of IGF-1 and pre-clinical data are numerous and overlapping, we included only the most relevant papers that also incorporated comprehensive reviews of other similar papers. We did, however, include all of the human clinical trials available since these were most relevant to the aim of this paper.

RESULTS

The therapeutic potential of IGF-1 was found to be relevant to the treatment of several CNS disorders, most notably Multiple Sclerosis, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and autism spectrum disorder. Table 1 categorizes the human clinical trials in specific CNS diseases.

Table 1. Clinical Trials with IGF-1 in CNS Disorders.

Overview of clinical trials using IGF-1 as a therapeutic agent in CNS disorders to date

| Intervention | Author and Year |

Sample Size |

Study Design |

Duration of Treatment |

Primary Outcome Measure |

Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Sclerosis |

rhIGF-1 | (J. A. Frank et al., 2002) | 7 | Open-label crossover |

6 months | Contrast enhancing lesion frequency on MRI |

Negative |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

rhIGF-1 | (Nagano, Shiote, et al., 2005) | 9 | Double- blind, randomized clinical |

9 months | Norris Scales | Positive |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

rhIGF-1 | (Lai et al., 1997) | 141 | Double blind, placebo controlled, parallel group |

9 months | Appel Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis rating scale |

Positive |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

rhIGF-1 | (Borasio et al., 1998) | 183 | Double blind, placebo controlled, parallel group |

9 months | Appel Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis rating scale |

Negative |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

rhIGF-1 | (Sorenson et al., 2008) | 330 | Double blind, placebo controlled, parallel group |

2 years | Rate of change in the averaged manual muscle testing score (MMT) |

Negative |

| Alzheimer’s Dementia |

MK-677 | (Sevigny et al., 2008) | 563 | Double blind, placebo controlled, parallel group |

12 months | Clinician’s Interview Based Impression of Change with caregiver input (CIBIC-plus) |

Negative |

| Phelan- McDermid syndrome |

rhIGF-1 | (Kolevzon et al., 2014) | 9 | Double blind, placebo controlled, crossover |

3 months | Aberrant Behavior Checklist-Social Withdrawal subscale |

Positive |

| Rett syndrome |

rhIGF-1 | (Khwaja et al., 2014) | 9 (MAD) 12 (OLE) |

Unblind multiple ascending dose and open label extension |

4 week MAD 20 week OLE |

Multiple Cardiorespiratory measures |

Positive |

Abbreviations: MK-677 = ibutamoren mesylate; MAD = multiple ascending dose; OLE = open-label extension

Neurodegenerative Disorders

Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immune-mediated neurologic disease that leads to neuronal deficits due to lesions in the white matter of the CNS and affects more than 2.5 million people worldwide (Rosati, 2001). The lesions in MS are caused by inflammatory insults to neuronal myelin sheaths, leading to overall demyelination of the neuron and disruption of action potentials. IGF-1 increases myelination in the brain and was studied using in vitro incubation of cell cultures from transgenic mice. To study possible reversal of myelin injuries, investigators subcutaneously administered 0.1 mg of rhIGF-1 twice daily to rats with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), which has been used extensively as an animal model for MS (Constantinescu, Farooqi, O’Brien, & Gran, 2011). Recombinant human IGF-1 in these models is hypothesized to promote oligodendrocyte progenitor populations. Although a transient decrease in CNS inflammation and disease severity was seen in the acute phase of treatment with rhIGF-1, chronic treatment showed no significant histopathological effect on remyelination (Cannella, Pitt Capello, & Raine, 2000). One of the possibilities accounting for this transient nature of effect of rhIGF-1 was found at the cytokine level. In comparison to the control group, decreased levels of transforming growth factor (TGF) β2 and β3 were seen in both acute and chronic IGF-1 treated groups. This is particularly important since TGF- β is expressed by astrocytes and has been found to play a role in oligodendrocyte differentiation (McKinnon, Piras, Ida, & Dubois-Dalcq, 1993) and reducing demyelination in another animal model for MS, Theiler’s virus model (Drescher, Murray, Lin, Carlino, & Rodriguez, 2000). The direct interaction of rhIGF-1 and TGF- β is unclear, but is important to explore in order to elucidate the exact role of rhIGF-1 in treatment of MS and its interaction with immune system cells and cytokines.

Li et al. (1998) performed a similar experiment using mice with EAE examining the effect of rhIGF-1 treatment on behavior and also on BBB defects and immunomodulatory macrophage activity in CNS lesions. Fifty-one mice with EAE were randomly assigned to four groups, two of which received placebo injections while the other two received 0.6mg/kg/day subcutaneous injections of rhIGF-1 after initial neuronal insults were clinically apparent. Limb strength studies along with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and histopathologic investigations revealed that rhIGF-1 treatment was associated with a significant increase in body weight, reduced severity of tail and limb weakness during acute attacks, and an overall reduction of lesions in the brain and spinal cord as compared to placebo-treated mice. Increased BBB permeability in the EAE mice was evident by increased albumin and inflammatory markers in brain and spinal cord sections and was considered a marker of acute inflammatory responses. This study showed that mice treated with rhIGF-1 had reduced numbers of extra- and intracellular anti-albumin immunoreactivities, indicating a reduction in inflammatory brain and spinal cord lesions after treatment. Immunostaining also showed a decrease in macrophage-like cells in the brain and spinal cords of mice treated with rhIGF-1, which was used as another marker for inflammatory lesions. Six mice were then randomly selected to receive continued treatment with rhIGF-1, but at twice the dose (1.2mg/kg/day), and this group showed a decrease in subsequent EAE attacks and a reduction of spinal cord lesions and areas without evidence of toxicity. These results furthered the hypothesis that rhIGF-1 treatment reduces neurologic deficits in EAE, CNS lesions size and number, and inflammatory responses (Li et al., 1998).

After preclinical results were promising, a clinical study was designed to test the efficacy of rhIGF-1 treatment in human patients with MS. In 2002, Frank et al. (2002) performed a pilot study in seven patients with MS who were administered rhIGF-1 0.05mg/kg subcutaneously twice daily for 6 months. This phase two open-label design used repeated MRI to evaluate the number of contrast enhancing lesions as the primary outcome measures in addition to several secondary outcome measures. After 24 weeks of rhIGF-1 treatment, there were no significant differences in inflammatory lesions detected by MRI and there was no significant change in clinical outcome measures (J. A. Frank et al., 2002).

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a motor neuron disease characterized by degeneration of both upper and lower motor neurons which leads to progressive muscle weakness, dysphagia, dyspnea and eventually death (Kiernan et al., 2011). Several growth factors serve as either protective factors against neuronal death or treatment for denervated muscle tissue, including IGF-1. Previous studies have established that IGF-1 promotes peripheral motor nerve regeneration, induces axonal sprouting, and increases neuro-muscular junction size and volume (Caroni & Grandes, 1990; Neff et al., 1993). Given the neuroprotective qualities of IGF-1, it has been proposed that it may play a role against motor neuron degeneration in ALS.

Mouse models of ALS show the characteristic muscular atrophy, motor neuron degeneration, and progressive partial denervation of skeletal muscle (Duchen & Strich, 1968; Harris & Ward, 1974) . Hantai et al. (1995) used daily administration of rhIGF-1 at 1 mg/kg in an ALS mouse model to demonstrate increased body weight (reflecting increased muscle mass), increased grip strength, and increased mean skeletal muscle fiber diameter (Hantai et al., 1995). Nagano et al. (2005) used intrathecal administration of rhIGF-1 in an ALS model system and found that continuous administration of both low-dose (0.1 mg/kg/day) and high-dose (1 mg/kg/day) rhIGF-1 delayed disease onset, reduced muscle atrophy, and extended life (Nagano, Ilieva, et al., 2005). Caroni and colleagues (1990) found daily subcutaneous injections of 0.1ng of rhIGF-1 induced marked axonal sprouting in adult rat or mouse gluteus muscles in vivo via activation of IGF1R (Caroni & Grandes, 1990), promoted peripheral motor nerve regeneration, and increased neuro-muscular junction size and volume (Caroni, 1993). These preclinical studies, in combination with two human post-mortem studies reporting up-regulated IGF-1 receptors in the spinal cord of patients with ALS, led to clinical trials with rhIGF-1 in patients with ALS (Adem et al., 1994; Dore, Krieger, Kar, & Quirion, 1996).

Nagano et al. (2005) performed a clinical trial to assess the effect of intrathecal administration of rhIGF-1 in patients with ALS. Of the 19 patients initially included in the study, nine were able to complete all treatment doses. These nine patients were assigned to low dose (0.0005 mg/kg) or high dose (0.003 mg/kg) administration of rhIGF-1 over six hours every 2 weeks for 40 weeks. The primary outcome measures were the forced vital capacity and Norris scales of bulbar and limb functioning. Results indicated that patients receiving high-dose rhIGF-1 had a modest beneficial effect on disease progression using Norris scales that was significantly different from the low-dose group. The forced vital capacity measure also showed a trend toward slower rate of deterioration in the high-dose group which did not reach statistical significance (Nagano, Ilieva, et al., 2005).

Lai et al. (1997) performed a double blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group study with subcutaneous rhIGF-1 in patients with ALS and studied disease progression. Two hundred and sixty-six patients enrolled and 141 completed the double blind study. Patients were randomly assigned to placebo, rhIGF-1 0.05 mg/kg/day, or rhIGF-1 0.1 mg/kg/day and were evaluated monthly for nine months. The primary outcome measures were the Appel ALS rating scale (AALS – quantitative estimate of bulbar, respiratory, and extremity functions) and the Sickness Impact Profile (SIP – patient-based quality of life measure). Administration of rhIGF-1 0.1mg/kg per day was associated with significant slowing of disease symptom progression, including muscle strength and respiratory function, and an increase in the quality of life in comparison with placebo and low dose IGF-1 (Lai et al., 1997).

While Lai et al (1997) was conducting this study in the United States, a similar study was underway in Europe led by Borasio and colleagues (1998). This study was also a double blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group study assessing the efficacy and safety of subcutaneous rhIGF-1 administration in patients with ALS. One hundred and eighty-three patients were randomized to rhIGF-1 0.1 mg/kg/day (124 patients) or placebo (59 patients). The primary outcome measures of this study were also the AALS and SIP. After nine months, the mean change in AALS was slightly higher in the placebo group and there was no significant change in the SIP scores from baseline between the groups. It was also noted that 15% of the patients in the rhIGF-1 group died, compared with 8% in the placebo group. However, a retrospective survival analysis revealed that two patients died of complications from unrelated medical comorbidities (suicide and paralytic ileus) while the rest died of respiratory failure and not adverse effects that have been associated with IGF-1.

Since the results from the aforementioned clinical trials were inconsistent, another randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase three clinical trial was devised by Sorenson et al (2008) to study the efficacy of rhIGF-1 treatment in ALS. Three hundred and thirty patients were randomized into two groups: rhIGF-1 0.05 mg/kg subcutaneously twice daily (167 patients) or placebo (163 patients). After two years, there were 150 subjects left in the rhIGF-1 group (85 deaths; 17 withdrew) and 152 subjects in the placebo group (83 deaths; 11 withdrew). The primary outcome measure was rate of change in the averaged manual muscle testing score (MMT) and the secondary measure was the revised ALS functioning rating scale (ALSFRS-r). There were no statistically significant changes in either outcome. Some limitations included the variable follow-up time for the patients and drug non-adherence, both of which may have confounded the results but are difficult to control in any study involving long-term follow-up and a progressive fatal disorder. The only adverse event that was significantly different between groups was hypoglycemia, occurring in 21 patients in the rhIGF-1 group and only 9 in the placebo group. Although this study did not show a statistically significant benefit of rhIGF-1 treatment over placebo for ALS, it does reaffirm that rhIGF-1 administration appears to be safe and well tolerated in most subjects (Sorenson et al., 2008).

Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disease that affects 1% of people over the age of 65 worldwide and is marked by slowness in voluntary movement, muscle rigidity, tremor and postural instability (Eberhardt & Schulz, 2003). IGF-1 has been described as a neuroprotective factor that antagonizes apoptosis and delays cell degeneration. Wang et al. (2010) explored the effect of IGF-1 to protect the death of dopaminergic neurons in an in vitro model of PD using a neurotoxin (MTPT; 1-methyl-4-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) to target dopaminergic neurons that has been used repeatedly in studies (Chiueh et al., 1984; Seniuk, Tatton, & Greenwood, 1990; Tatton & Kish, 1997). IGF-1 was administered to neuronal cell cultures at levels of 0.00001mg, 0.00005mg, 0.0002mg and 0.0004mg for 24hrs after inducing dopaminergic cell apoptosis and was found to increase the survival of these cells by reducing apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner. The mechanism of cell survival was also explored in this study using Western blot analysis to detect phosphorylated markers in various pathways. After IGF-1 treatment, there was increased phosphorylation of MAPK/ERK, which caused inhibition of caspase-3 and −9. IGF-1 treatment also activated the PI3K/AKT pathways to suppress GSK-3β production and effectively suppress the pro-apoptotic JNK pathway (Wang et al., 2010).

Ebert et al. (2008) also examined the effect of IGF-1 to restore dopaminergic neuron function in a rat model of PD. In this study, 40 adult rats were injected unilaterally with 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) to deplete nigrostriatal DA and produce behavioral deficits that mimic PD in humans (Deumens, Blokland, & Prickaerts, 2002). Human neural progenitor cells that either produced glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) or IGF-1 were then transplanted into the striatum of the rat brain. Only IGF-1 transplanted rats showed increased proliferation of dopaminergic neurons. This study confirms the ability of IGF-1 to promote cell survival and proliferation of dopaminergic neurons (Ebert, Beres, Barber, & Svendsen, 2008). Although no human clinical trials have been published to date, in vivo data in rats suggests that IGF-1 treatment could have positive effects in the treatment of PD.

Alzheimer’s Dementia

Alzheimer’s Dementia (AD) is defined as a cognitive decline in memory, language, executive functioning, learning, and motor movements that affects over 26 million people worldwide. The cause of AD has been related to aggregation of beta-amyloid in the brain, extracellular Aβ protein aggregation, and inflammation leading to neuronal apoptosis (C. Ballard et al. 2011; Murphy & LeVine, 2010; Roberts et al., 2008). Although several studies showed that circulating serum levels of IGF-1 are diminished and expression of IGF1R is downregulated in patients with AD, these studies had small sample sizes and/or included confounding genetic variance (Murialdo et al., 2001; Mustafa et al., 1999). Duron et al. (2012) conducted a large, multicentered, cross-sectional study to assess the relationship between IGF-1 and cognitive decline. A total of 694 subjects were grouped into either AD, mild cognitive impairment, or controls based on well validated diagnostic criteria. The mean IGF-I and IGFBP-3 serum levels were then obtained for each group and results indicated that there are significantly lower serum levels of IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 in men with AD. This statistical difference was not observed in women despite adjustment for confounding variables, leading to the overall conclusion that serum IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels are implicated in men with AD (Duron et al., 2012).

After the discovery that lower IGF-1 levels are associated with AD, trials were conducted to explore the therapeutic properties of IGF-1 in mice with increased cerebral beta-amyloid plaques (Moloney et al., 2010; Mustafa et al., 1999; Watanabe et al., 2005). Carro et al. (2002) showed that in aged mice, serum IGF-1 modulated brain levels of beta-amyloid by inducing its clearance via carrier proteins like albumin and transthyretin (Carro, Trejo, Gomez-Isla, LeRoith, & Torres-Aleman, 2002). In addition, Freude et al (2009) showed that resistance to IGF-1 delayed amyloid accumulation and prevented premature death in mouse models of AD (Freude et al., 2009). Together, these results implicated IGF-1 signaling in the role of beta-amyloid metabolism, leading to its study in human clinical trials.

Sevigny et al. (2008) conducted a double-blind, multicentered study using growth hormone secretagogue MK-677 (ibutamoren mesylate) which stimulates upregulation and circulation of IGF-1 to assess efficacy in slowing disease progression in patients with AD. After screening, 563 patients with mild to moderate AD were randomized to receive either MK-677 25 mg or placebo administration orally for 12 months. The primary outcome measure was the Clinician’s Interview Based Impression of Change with caregiver input (CIBIC-plus), in addition to several secondary outcome measures (e.g., cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living, and the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes). Although there was a 60% increase in serum IGF-1 levels at 6 months and a 73% increase at 12 months, there were no significant changes from baseline in any of the clinical outcome measures. Thus, the increased levels of serum IGF-1 did not appear to slow the rate of cognitive decline in AD (Sevigny et al., 2008).

Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Phelan-McDermid Syndrome

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental and genetically heterogeneous syndrome characterized by social and language impairments, in addition to restrictive and repetitive behaviors and sensory sensitivities (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Approximately 10–20% of ASD cases have a known genetic etiology and increased use of genome-wide arrays and re-sequencing efforts have identified many single gene causes of ASD (Betancur, 2011), including the SHANK3 gene. Loss of SHANK3, either through deletion or mutation, causes Phelan-McDermid syndrome (PMS), which is characterized by global developmental delay, motor skills deficits, delayed or absent speech, and ASD (Soorya et al., 2013). The SHANK3 gene is located on the terminal region of the long arm of chromosome 22 and codes for a key scaffolding protein in the postsynaptic density of glutamatergic synapses and plays a critical role in synaptic function (Boeckers, 2006). Loss of SHANK3 is responsible for at least 0.5% of ASD cases (Durand et al., 2007) and up to 2% of ASD with moderate to profound intellectual disability (ID) (Leblond et al., 2014) . ASD is estimated to affect 1 in 68 children (Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year Principal, Centers for Disease, & Prevention, 2014) and represents a major public health concern given the total annual societal cost of ~$35–50 billion associated with caring for ASD individuals over their lifetime (Ganz, 2007). Although SHANK3 deletions and mutations explain a relatively small proportion of ID and ASD cases, SHANK3 and the glutamate signaling pathway is common to multiple monogenic forms of ID and ASD. In addition, many different genetic causes of ID and ASD, like Fragile X syndrome (FXS), converge on several underlying pathways, including the SHANK3 pathway (Darnell et al., 2011; Sakai et al., 2011).

SHANK3 protein is found in the post-synaptic junction of excitatory synapses like NMDA-, AMPA-, and metabolic glutamate receptor complexes. During development, the mRNA of SHANK3 is concentrated in various parts of the cortex, hippocampus and the granule cell layer of the cerebellum. In addition to its role as a scaffolding protein, it also facilitates cross-talk between various receptor signaling pathways (Boeckers et al., 1999; Sheng & Kim, 2000). To study the effect of SHANK3 on developing neurons in vitro, hippocampal neurons were removed from 5–7 day postnatal rats and inhibited from expressing Shank3, resulting in a reduced number and length of dendritic spines. When treated with Shank3 protein, hippocampal neurons displayed an increased number of dendritic spines and recruited functional glutamate receptors (Roussignol et al., 2005). This observation, among other studies, lead to the development of mouse model systems with targeted disruption of the Shank3 gene.

Bozdagi and colleagues (2010) examined synaptic transmission and plasticity in Shank3-deficient mice by multiple electrophysiological methods. Results indicated a reduction in basal neurotransmission in Shank3 -deficient mice due to reduced AMPA receptor-mediated transmission and reflecting less mature synapses. Long term potentiation (LTP), a critical measure of learning and memory capacity, was impaired in Shank3-deficient mice, with no significant change in long term depression (LTD) (Bozdagi et al., 2010). Behaviorally, male Shank3-deficient mice also exhibited less social sniffing and made fewer ultrasonic vocalizations during interactions with estrus female mice, as compared to controls (Bozdagi et al., 2010). Wang and colleagues (2011) also observed behavioral changes in a Shank3-deficient mouse model including enhanced repetitive behavior, aberrant social and long-term memory, and impaired motor skills.

Bozdagi and colleagues (2013) administered IGF-1 to assess whether treatment could reverse deficits in Shank3-deficient mice. Intraperitoneal injection of rhIGF-1 at clinically approved doses of 0.24 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks reversed the electrophysiological deficits seen in the mice. Shank3-deficient mice no longer demonstrated reduced AMPA receptor-mediated transmission and showed normal LTP comparable to the wildtype controls. Motor performance and motor learning were also assessed in the model system by measuring time latencies to fall off a rotating rod. After IGF-1 treatment, Shank3-deficient mice exhibited significantly longer latencies in comparison to saline-injected mice of the same genotype (Bozdagi, Tavassoli, & Buxbaum, 2013).

Another recent study examined the in vitro effects of IGF-1 on recombinant neurons using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from patients with PMS. PMS neurons contained significantly reduced levels of SHANK3 mRNA and protein expression and exhibited a reduced response to AMPA- and NMDA-mediated electrical stimuli, indicating impaired synaptic transmission. The change in excitatory response in PMS neurons was not accompanied by a change in inhibitory response, even after controlling for receptor density and availability. The imbalance of excitatory and inhibitory neuronal response was found to be caused by a decreased number of AMPA and NMDA receptors, faster rate of NMDA-receptor decay, and no change in GABA receptor expression in PMS neurons (Shcheglovitov et al., 2013). In an attempt to reverse the structural and electrophysiological deficits, IGF-1 was administered and strengthened the response to AMPA- and NMDA-mediated stimuli and reduced the rate of decay of NMDA-receptors.

A clinical trial with rhIGF-1 in children with PMS is currently underway (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01525901) and results from a pilot study demonstrated preliminary evidence of safety, tolerability, and efficacy (Kolevzon et al., 2014). In this pilot, nine children with PMS aged 5 to 15 years old were randomized to rhIGF-1 or placebo in a cross-over design. Subjects received treatment with rhIGF-1 and placebo, in random order, for 12 weeks each, separated by a four week wash-out period and rhIGF-1 was titrated to a maximum dose of 0.24 mg/kg/day in divided doses. rhIGF-1 was associated with significant improvement in both social impairment on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist Social Withdrawal subscale (ABC-SW) (Aman, Singh, Stewart, & Field, 1985) and restrictive behaviors using the Repetitive Behavior Scale (RBS-R) (Bodfish, Symons, & M.H., 1999). There were no serious adverse events in any participants and this study established the feasibility of rhIGF-1 treatment in PMS (Kolevzon et al., 2014).

Fragile X Syndrome

FXS is an X-linked disease caused by a mutation in the Fmr1 gene, which codes for the fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP), another ASD-associated protein. Mutation of Fmr1 results in significant cognitive impairment, motor and speech delay, stereotypic movements, impaired social interactions, and seizures (Garber, Visootsak, & Warren, 2008). FMRP binds to neuronal mRNA during early development to regulate protein translation in dendritic spines and post-synaptic structures (Segal, Korkotian, & Murphy, 2000). Although its exact mechanism in CNS development is largely unknown, FMRP has been shown to temporarily stall mRNA translation (Darnell et al., 2011) and prune redundant or dysfunctional neuronal connections and cell types (Patel, Loerwald, Huber, & Gibson, 2014; Pilpel et al., 2009).

On a cellular level, both human Fragile X neurons and Fmr1 knockout mice have an abundance of dysmorphic dendritic spines and immature synapse formation, (Comery et al., 1997; Galvez & Greenough, 2005; Irwin, Galvez, & Greenough, 2000) thought to be caused by alterations in the PI3K/mTOR and MAPK/ERK signaling pathways (Hoeffer et al., 2012; Kumar, Zhang, Swank, Kunz, & Wu, 2005). Electrophysiological studies of hippocampal neurons in Fmr1 knockout mice not only confirmed aberrant activation of PI3K/mTOR and MAPK/ERK pathways (Deacon et al., 2015), but also revealed reduced response to excitatory synaptic currents and enhanced glutamate receptor dependent LTD, suggesting the importance of FMRP, PI3K/mTOR and MAPK/ERK pathways, and glutamate receptor functioning underlying deficits in FXS (Braun & Segal, 2000; Huber, Gallagher, Warren, & Bear, 2002). The disruption of neuronal circuitry in Fmr1 knockout mice leads to similar clinical phenotypes of FXS, including anxiety/hyperactivity, impaired short-term and long-term memory, and impaired social interactions (Deacon et al., 2015; Yan, Rammal, Tranfaglia, & Bauchwitz, 2005).

Deacon et al. (2015) used Fmr1 knockout mice as a preclinical model for FXS by studying the effect of NNZ-2566, (1–3)IGF-1 analog, on the cellular and behavioral deficits in FXS. For 28 days, intraperitoneal administration of NNZ-2566 100mg/kg was administered daily to Fmr1 knockout mice (N=5) and compared to wild-type mice using Western blot analysis of MAPK/ERK and PI3K/mTOR activation and behavior analysis of anxiety/hyperactivity and social interactions. Treatment of Fmr1 knockout mice with NNZ-2566 resulted in normalization of phosphor-ERK and phosphor-Akt levels and reduction of dendritic spine neurons, indicating a reversal of MAPK/ERK and PI3K/mTOR signaling abnormalities and correction of dendritic spine morphology. The Fmr1 knockout mice also displayed lower anxiety levels, reduced hyperactivity, improved short-term and long-term memory, improvement in learning and LTP, and normalized social recognition and behaviors (Deacon et al., 2015). The lack of adverse events and positive therapeutic profile in preclinical trials with Fmr1 mice provides evidence for IGF-1 as a potential therapeutic agent in FXS and there is an ongoing clinical trial in phase II with the IGF-1 analogue, NNZ-2566.

Rett Syndrome

Rett syndrome is a developmental disorder associated with ASD and characterized by a rapid deceleration in growth, regression in motor and language skills, autonomic dysfunction such as apnea, and cognitive impairment that affects 1 in 10,000 live female births (Hagberg, 2002). The cause of Rett syndrome has been linked to a mutation in Xq28, the gene encoding MeCP2, which is a global transcriptional modulator (Amir et al., 1999). Results with studies of iPSCs derived from fibroblasts of patients with Rett syndrome indicate that neurons with MeCP2 mutations have a reduced number of synapses and dendritic spines, in addition to altered calcium signaling and other electrophysiological defects. Animal models of Rett syndrome, using MeCP2 mutant alleles, were observed to have normal development until 5 weeks of age, when they began to exhibit abnormal behaviors resembling those seen in Rett patients, including abnormal gait, tremors, reduced locomotor activity, abnormal paw clasping and premature death (Collins et al., 2004; Johnston, Jeon, Pevsner, Blue, & Naidu, 2001; Luikenhuis, Giacometti, Beard, & Jaenisch, 2004). To explore the neuronal pathology underlying these behaviors, pyramidal neurons were extracted and isolated from MeCP2 mutant rats to reveal a four-fold decrease in spontaneous neuronal firing; MeCP2 deletion shifted the balance between excitation and inhibition to reduce net excitatory drive. This alteration in the cortical circuitry resulted in decreased neuronal activity and may also reduce long-term potentiation, which has been observed in MeCP2 mutant mice (Collins et al., 2004; Dani et al., 2005).

Tropea et al. (2009) studied in vivo (1–3)IGF-1 treatment in Rett syndrome by using MeCP2 mutant mice. Knockout mice were treated with either 10mg/kg or 20 mg/kg of (1–3)IGF-1 intraperitoneal injections daily for 14 days, starting at 2 weeks of age. Initial observations showed that the (1–3)IGF-1 treated mice had a 50% increase in life expectancy, increased levels of locomotor activity, and more stable autonomic parameters when breathing and heart rate were monitored. Immunohistochemical studies showed that (1–3)IGF-1 treatment led to an increase in brain size and an increase in the post-synaptic excitatory scaffold protein PSD-95, which promotes synapse maturation and influences synaptic plasticity. Increased dendritic spine formation was also found and electrophysiology studies demonstrated increased excitatory synaptic transmission in the sensorimotor cortex (Tropea et al., 2009). In a similar study, Castro et al. (2004) used rhIGF-1 to treat MeCP2 mutant mice with intraperitoneal injections of either 0.25mg/kg or 2.5mg/kg daily for 14 days and demonstrated an overall reversal of neuronal circuitry signaling, improved social behaviors, and increased plasticity in developing neurons (Castro et al., 2014). The significant reversal of electrophysiological and phenotypic deficits of mouse and neuronal models of Rett syndrome with IGF-1 suggested its promise as a pharmacologic treatment for patients with Rett syndrome and clinical trials were soon developed.

Khwaja and colleagues (2014) performed a four week multiple ascending dose (MAD) and 20 week open-label extension (OLE) trial to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics of rhIGF-1 treatment in Rett syndrome. Twelve girls with MECP2 mutations received 0.040 mg/kg subcutaneous injections twice daily during the first week, 0.08 mg/kg during the second week, and 0.12 mg/kg for the last two weeks. Using a BioRadio device to evaluate breathing, there was an overall significant improvement in the apnea index between baseline of the MAD and the end of the OLE. Heart rate variability also decreased, but not significantly. There was also an overall improvement in anxiety and depressive symptoms during the OLE, but these changes were not statistically significant. rhIGF-1 was well tolerated with no serious adverse events. Importantly, CSF and serum analysis at the end of the MAD also revealed a significant increase in IGF-1 levels after treatment with rhIGF-1. These results indicate that not only is rhIGF-1 administration beneficial in reversing autonomic dysfunction in Rett syndrome, but it is also well tolerated in humans with a neurodevelopmental disorder (Khwaja et al., 2014). Although this was the first trial to publish data on rhIGF-1 administration in Rett syndrome to date, other clinical trials are underway (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01777542). In addition, other studies are examining the effect of a synthetic analogue of (1–3)IGF-1 (NNZ-2566, Neuren Pharmaceuticals) in Rett syndrome (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT01703533) and in FXS (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT01894958).

DISCUSSION

During CNS development, many biologic factors ensure proper differentiation, migration, cell growth and survival of neurons. These factors have become the focus of many studies attempting to elucidate the molecular and cellular causes of CNS diseases in order to develop novel, targeted, and potentially disease modifying therapeutics. IGF-1 in particular has received significant attention because it is a commercially available compound that crosses the BBB, is well tolerated, and has beneficial effects on synaptic development by promoting neuronal cell survival, synaptic maturation and plasticity. Because of these observed effects in both in vitro and in vivo studies, several clinical trials have been performed to study the clinical therapeutic effect of rhIGF-1 in CNS disorders.

Clinical trials with rhIGF-1 in MS, ALS, PD, and AD have led to mixed results. One study in MS showed no significant differences in inflammatory lesions detected by MRI or clinical outcome measures. rhIGF-1 use in ALS led to a significant retardation of disease progression, increased muscle strength, improved respiratory functioning and an increase in quality of life in two studies, but did not show significant change in two follow-up studies. In PD, human clinical trials have not yet been performed, but preclinical studies provide evidence that rhIGF-1 protects against apoptosis of dopaminergic neurons and leads to behavioral improvement in rats. In AD, growth hormone secretagogue MK-677 (ibutamoren mesylate) successfully stimulated IGF-1 release, but was not associated with improvement in clinical outcomes.

The discrepancy in results between clinical and preclinical studies on a cellular and molecular level still remains largely unexplained and attempts to do so have revealed even more complexity. For example, IGF-1 is cleaved into two products and although they have overlap in their mechanism of action, both have independent actions based on cell type and location in the brain and both can also act in a paracrine fashion to regulate local IGF-1 production. The immediate downstream effects of IGF-1 also vary, depending on cell type, presence of other molecules that may either down- or up-regulate IGF-1 action, and interactions with numerous interconnected pathways. The discrepant outcomes between preclinical and clinical studies with IGF-1, combined with its various potential mechanisms of action in the CNS, highlight the importance of thorough and rigorous preclinical evaluations using multiple preclinical models to establish a safe, consistent and efficacious dosing regimen for individual CNS disorders. Although the mechanisms responsible for proper CNS development have yet to be completely understood, there are several pathways that have consistently been implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders. IGF-1 not only has significant interactions with pathways that underlie several neurodevelopmental disorders, but exogenous administration is also effective in reversing phenotypic and electrophysiological changes caused by aberrations in these pathways. To understand the therapeutic mechanism of action of IGF-1 in neurodevelopmental disorders, we must first explore the genetic and molecular etiology of ASD.

Several studies have been dedicated to uncovering common pathways in neurodevelopmental disorders associated with ASD, such as PMS, Rett syndrome, and FXS. Since this heterogeneous group of disorders has some common clinical symptoms, including ASD and ID, these studies were aimed at finding disruptions in common pathways responsible for proper cell growth, differentiation and survival. This proves to be a difficult task since there are many proteins that have been implicated in ASD, including transcription factors, scaffolding proteins, and various enzymes. By developing a protein interactome using extracted whole mouse brains and gene expression analysis, Sakai and colleagues (2011) demonstrated important interactions between known ASD-associated proteins, which included SHANK3 (PMS), MeCP2 (Rett), and FMRP (FXS) (Sakai et al., 2011). It was recently discovered that MeCP2 also regulates the expression of certain isoforms of SHANK3 protein, which further supports the molecular overlap in the diseases that cause ASD (Waga et al., 2014).

As previously mentioned, SHANK3 is a major scaffolding protein found in the post-synaptic densities of mGlur-, AMPA-, and NMDA-receptor mediated complexes and is integral to their proper formation and functionality during development. Insufficiency of SHANK3 gene expression leads to PMS and neuronal tissue samples from Shank-deficient mice reveal immature glutamatergic synapses, smaller and fewer dendritic spines, decreased numbers of AMPA and NMDA receptors, decreased synaptic expression of other scaffolding proteins, and a reduction of response to AMPA and NMDA-receptor mediated excitatory stimuli. Reduced response to glutamate has a particularly devastating effect on LTP, a cellular phenomenon responsible for learning and memory. IGF-1 has reversed deficits in mouse (Bozdagi et al., 2013) and human neuronal (Shcheglovitov et al., 2013) models of PMS and is currently being administered as a therapeutic agent in a study in children with PMS, the preliminary results of which are promising (Kolevzon et al., 2014).

MeCP2 is a global transcription modulator responsible for synapse and dendrite formation during development, and mutations in MeCP2 cause Rett syndrome. Neurons isolated from both humans and mice with mutations in MeCP2 have increased immature synapses, reduced number of synapses, fewer dendritic spines, altered calcium signaling, decreased net response to excitatory electrical stimulation and reduced LTP. Treatment with (1–3)IGF-1 reverses the electrophysiological and behavioral deficits in mice with mutated MeCP2. One human study has shown improvement in autonomic functioning and overall tolerability in humans with Rett syndrome (Khwaja et al., 2014), and another study is currently underway. An IGF-1 analogue, NNZ-2566, is also being studied in Rett syndrome and preliminary data from a multi-centered randomized controlled trial released by the manufacturer report both efficacy and tolerability (http://www.neurenpharma.com/IRM/Company/ShowPage.aspx/PDFs/1448-10000000/NeurensuccessfulinRettsyndromePhase2trial).

CONCLUSION

The extensive investigation of the effect of IGF-1 during development and the continued discovery of its diverse roles throughout the CNS exemplifies the presence of common underlying pathways responsible for neuronal development. Although many different genetic mutations and disrupted pathways lead to syndromes associated with ASD, there is significant overlap in their molecular and electrophysiological deficits. Specific deficits in synaptic function and plasticity in glutamate signaling have been consistently documented in various forms of ASD using mouse and human neuronal models and have been rescued with IGF-1. The link between synapse dysfunction and ASD suggest that treatment with IGF-1 may also have implications for ASD associated with disruptions in common underlying pathways. Preliminary studies in children with PMS and Rett syndrome have been successful, and IGF-1 may also be a promising therapeutic candidate in other single gene causes of ASD and perhaps in idiopathic ASD; a trial is underway with IGF-1 in ASD defined broadly (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01970345). Although definitive studies are needed, pilot data suggest the promise of IGF-1 in neurodevelopmental disorders associated with ASD.

Highlights.

IGF-1 is necessary for proper development of the central nervous system

IGF-1 dysregulation leads to neuronal dysfunction and severe developmental disorders

IGF-1 may be a safe and potentially effective treatment for several CNS disorders

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Beatrice and Samuel A. Seaver Foundation, the National Institute of Mental Health (MH100276-01 to AK), and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U54 NS092090-01 to AK). We would also like to thank the many families that work with us to understand neurodevelopmental disability.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Adem A, Ekblom J, Gillberg PG, Jossan SS, Hoog A, Winblad B, Sara V. Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptors in human spinal cord: changes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1994;97(1):73–84. doi: 10.1007/BF01277964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aikin R, Maysinger D, Rosenberg L. Cross-talk between phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT and c-jun NH2-terminal kinase mediates survival of isolated human islets. Endocrinology. 2004;145(10):4522–4531. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleman A, Verhaar HJ, De Haan EH, De Vries WR, Samson MM, Drent ML, Koppeschaar HP. Insulin-like growth factor-I and cognitive function in healthy older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(2):471–475. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.2.5455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG, Singh NN, Stewart AW, Field CJ. The aberrant behavior checklist: a behavior rating scale for the assessment of treatment effects. Am J Ment Defic. 1985;89(5):485–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, A. P. A. D. S. M. T. F. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. 2013 from http://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/book.aspx?bookid=556.

- Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat Genet. 1999;23(2):185–188. doi: 10.1038/13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson IK, Edwall D, Norstedt G, Rozell B, Skottner A, Hansson HA. Differing expression of insulin-like growth factor I in the developing and in the adult rat cerebellum. Acta Physiol Scand. 1988;132(2):167–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1988.tb08314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsenijevic Y, Weiss S. Insulin-like growth factor-I is a differentiation factor for postmitotic CNS stem cell-derived neuronal precursors: distinct actions from those of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Neurosci. 1998;18(6):2118–2128. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-02118.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach MA, Shen-Orr Z, Lowe WL, Jr, Roberts CT, Jr, LeRoith D. Insulin-like growth factor I mRNA levels are developmentally regulated in specific regions of the rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1991;10(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(91)90054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AM, Batchelor DC, Thomas GB, Wen JY, Rafiee M, Lin H, Guan J. Central penetration and stability of N-terminal tripeptide of insulin-like growth factor-I, glycine-proline-glutamate in adult rat. Neuropeptides. 2005;39(2):81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker J, Liu JP, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A. Role of insulin-like growth factors in embryonic and postnatal growth. Cell. 1993;75(1):73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard C, Gauthier S, Corbett A, Brayne C, Aarsland D, Jones E. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2011;377(9770):1019–1031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard FJ, Knowles SE, Walton PE, Edson K, Owens PC, Mohler MA, Ferraiolo BL. Plasma clearance and tissue distribution of labelled insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I), IGF-II and des(1-3)IGF-I in rats. J Endocrinol. 1991;128(2):197–204. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1280197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballotti R, Nielsen FC, Pringle N, Kowalski A, Richardson WD, Van Obberghen E, Gammeltoft S. Insulin-like growth factor I in cultured rat astrocytes: expression of the gene, and receptor tyrosine kinase. EMBO J. 1987;6(12):3633–3639. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02695.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker AJ, Ullian EM. Astrocytes and synaptic plasticity. Neuroscientist. 2010;16(1):40–50. doi: 10.1177/1073858409339215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor DC, Lin H, Wen JY, Keven C, Van Zijl PL, Breier BH, Thomas GB. Pharmacokinetics of glycine-proline-glutamate, the N-terminal tripeptide of insulin-like growth factor-1, in rats. Anal Biochem. 2003;323(2):156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter RC, Martin JL, Beniac VA. High molecular weight insulin-like growth factor binding protein complex. Purification and properties of the acid-labile subunit from human serum. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(20):11843–11848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck KD, Powell-Braxton L, Widmer HR, Valverde J, Hefti F. Igf1 gene disruption results in reduced brain size, CNS hypomyelination, and loss of hippocampal granule and striatal parvalbumin-containing neurons. Neuron. 1995;14(4):717–730. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90216-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]