Significance

Mechanistic understanding of proteasome function requires elucidation of its three-dimensional structure. Previous investigations have revealed increasingly detailed information on the overall organization of the yeast 26S proteasome. In this study, we further improved the resolution of cryo-EM structures of endogenous proteasomes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. These structures reveal two distinct conformational states, which appear to correspond to different states of ATP hydrolysis and substrate binding. This information may guide future functional analysis of the proteasome.

Keywords: protein degradation, proteasome, cryo-EM, structure

Abstract

The eukaryotic proteasome mediates degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins. Here we report the single-particle cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures of the endogenous 26S proteasome from Saccharomyces cerevisiae at 4.6- to 6.3-Å resolution. The fine features of the cryo-EM maps allow modeling of 18 subunits in the regulatory particle and 28 in the core particle. The proteasome exhibits two distinct conformational states, designated M1 and M2, which correspond to those reported previously for the proteasome purified in the presence of ATP-γS and ATP, respectively. These conformations also correspond to those of the proteasome in the presence and absence of exogenous substrate. Structure-guided biochemical analysis reveals enhanced deubiquitylating enzyme activity of Rpn11 upon assembly of the lid. Our structures serve as a molecular basis for mechanistic understanding of proteasome function.

The eukaryotic ubiquitin–proteasome system is responsible for the degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins (1). The 26S proteasome consists of one 20S core particle (CP) and two 19S regulatory particles (RPs). The RP is divided into the lid and base assembly intermediates (1). The lid comprises nine Rpn subunits in yeast (Rpn3/5/6/7/8/9/11/12/15) and the base comprises three Rpn subunits (Rpn1/2/13) and six ATPases (Rpt1–6). Rpn10, which consists of an N-terminal von Willebrand factor A (VWA) domain and multiple C-terminal ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIM), connects the lid and the base. Polyubiquitin (poly-Ub) chains from substrate are recognized by the RP, leading to unfolding of the substrate and its translocation into the CP, where it is degraded.

The main function of the lid is to remove poly-Ub chains from the substrate (1). The released Ub chains are recycled via further cleavage into Ub monomers. Six of the nine Rpn subunits in the lid (Rpn3/5/6/7/9/12) contain a solenoid fold followed by a proteasome-CSN-eIF3 (PCI) domain of varying lengths; for Rpn8 and Rpn11, each has an Mpr1–Pad1–N-terminal (MPN) domain. Among all Rpn subunits, Rpn11 is the only deubiquitylating enzyme (DUB); it cleaves the isopeptide bond between the carboxyl terminus of Ub and the ε-amino group of Lys in the substrate (2, 3). Except for Rpn15/Sem1/Dss1, the C-terminal sequences of the other eight Rpn subunits in the lid form a helix bundle, which dictates lid assembly (4, 5).

In the base, the six Rpt subunits form a hexameric ring. Powered by ATP hydrolysis, the Rpt ring is responsible for substrate unfolding and translocation of the unfolded substrate through the narrow RP central channel into the CP for degradation (6–8). The barrel-shaped CP consists of two outer α-rings and two inner β-rings, each containing seven subunits (α1–7 or β1–7). X-ray structures of the CP at atomic resolution have been reported for archaeabacteria (9), yeast (10), and mammals (11).

Crystallization of the RP or the 26S proteasome is hampered by its dynamic nature. Improvement of cryo-EM technologies has allowed structural determination of the proteasome at varying resolutions (8, 12–18). Eight Rpn subunits were identified in the lid by cryo-EM analysis of the proteasome from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cerevisiae) (8) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (S. pombe) (12). The cryo-EM structure of an intact proteasome from S. cerevisiae was determined at 7.4-Å resolution, which allowed identification and modeling of all RP subunits (13, 19). These advances were followed by identification of distinct conformational states of the proteasome (15–17). In this manuscript, we report the cryo-EM structures of the S. cerevisiae 26S proteasome at improved resolutions, describe important structural features, and identify two distinct conformational states of the proteasome that are shared with other reported structures.

Results

Sample Preparation and Electron Microscopy.

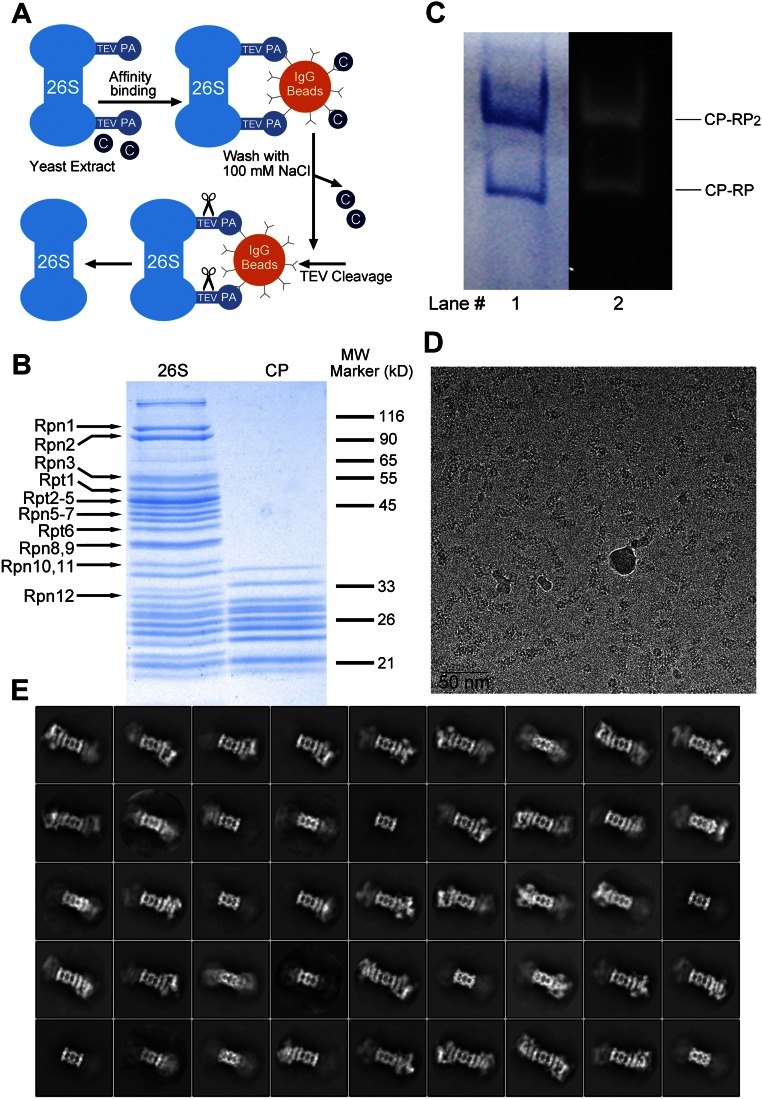

Following a published protocol (20), we purified the S. cerevisiae proteasome. Approximately 3.3 mg purified sample was obtained from a 12-L culture (Fig. S1 A and B). Analysis of the purified sample by native PAGE revealed two major species of 2:1 and 1:1 stoichiometry between the RP and CP (Fig. S1C, lane 1). Incubation of the native PAGE gel with the fluorogenic substrate Sucrose-Leu-Leu-Val-Try-7-Amido-4-Methylcoumarin (Suc-LLVY-AMC) confirmed the proteolytic activity of the two proteasomal species (Fig. S1C, lane 2).

Fig. S1.

Purification, characterization, and cryo-EM analysis of the 26S proteasome from S. cerevisiae. (A) A schematic diagram of the affinity-purification protocol for the endogenous proteasome from S. cerevisiae. PA denotes the Protein A tag. (B) Identification of the Rpn and Rpt subunits by SDS/PAGE. The proteasome was applied to SDS/PAGE followed by Coomassie staining. The isolated CP is shown as a control. (C) The purified proteasome has proteolytic activity. The purified proteasome appeared as two distinct bands on native PAGE: 2:1 and 1:1 complexes between the RP and the CP (lane 1). The native PAGE gel was incubated with the fluorogenic substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC, and degradation of the substrate was detected by fluorescence emission of the free AMC moiety (lane 2). (D) A representative cryo-EM micrograph collected on the Titan Krios electron microscope. Many particles of the proteasome are clearly visible. (Scale bar, 50 nm.) (E) Representative reference-free 2D class averages of the proteasome particles. The original micrographs were collected on the Titan Krios electron microscope.

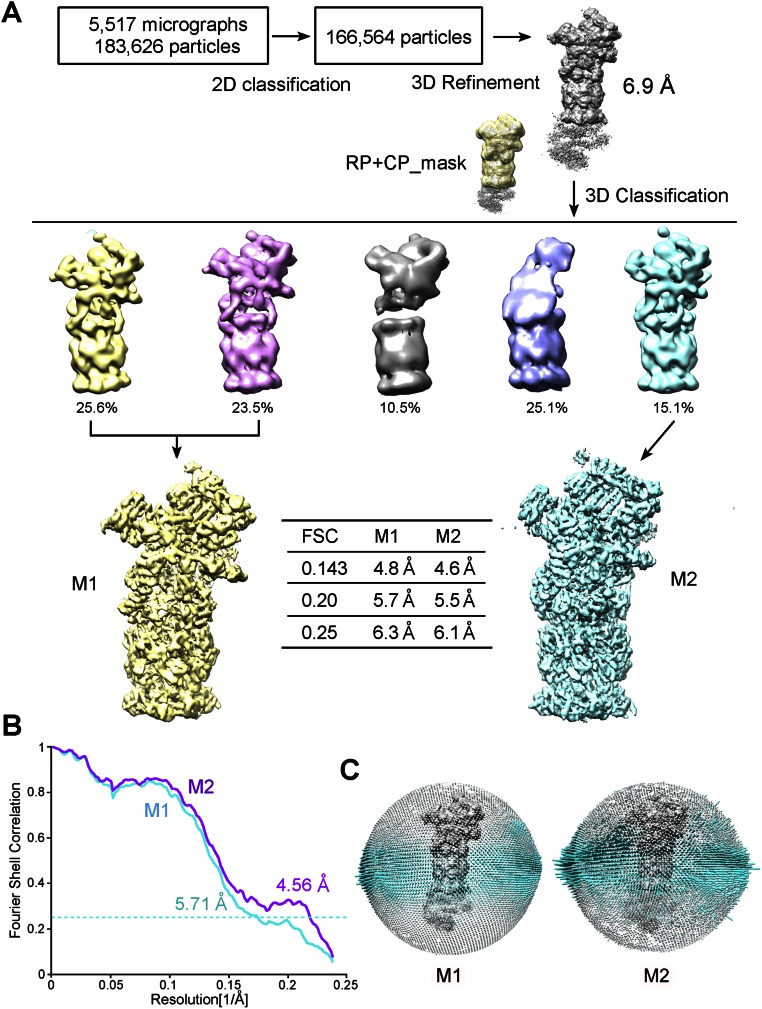

The purified proteasome was imaged on a Titan Krios electron microscope (Fig. S1D); 183,626 particles were semiautopicked from 5,517 micrographs. After reference-free two-dimensional (2D) classification (Fig. S1E), 166,564 particles were subjected to three-dimensional (3D) refinement, followed by 3D classification with a mask on the CP and one RP (Fig. S2A); 81,782 particles from two classes and 25,151 particles from another class were subjected to an autorefine subroutine. These two reconstructions may represent distinct conformations of the proteasome, designated the M1 and M2 states (Fig. S2 B and C). The final cryo-EM maps for the M1 and M2 states have overall resolutions of 4.8 and 4.6 Å, respectively, on the basis of the gold-standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC) value of 0.143 (Fig. 1 A–C). For both reconstructions, the FSC curves shift to the right around 5–6 Å, and thus may yield inflated resolutions (Fig. 1C). The overall resolutions for the M1 and M2 states are adjusted to 6.3 and 6.1 Å, respectively, based on the FSC value of 0.25.

Fig. S2.

Cryo-EM analysis of the yeast proteasome. (A) A flow chart for the Titan Krios cryo-EM data processing of the yeast proteasome; 183,626 particles were subjected to 2D classification and subsequent 3D refinement, producing a reconstruction at an average resolution of 6.9 Å. A large mask covering the CP and one RP was applied to 3D classification; 49.1% of all of the remaining particles were used to calculate the M1 conformation, and 15.1% of the particles gave rise to the M2 conformation. Three different resolution estimates are indicated, each using a different FSC value. Please refer to SI Materials and Methods for details. Structural images in this figure, and all other figures except Fig. S5, were prepared using Chimera (33). (B) FSC curves of the final models versus the cryo-EM maps are shown for the M1 and M2 states. (C) Angular distributions for the final reconstruction of the M1 and M2 states of the proteasome. Each cylinder represents one view, and the height of the cylinder is proportional to the number of particles for that view.

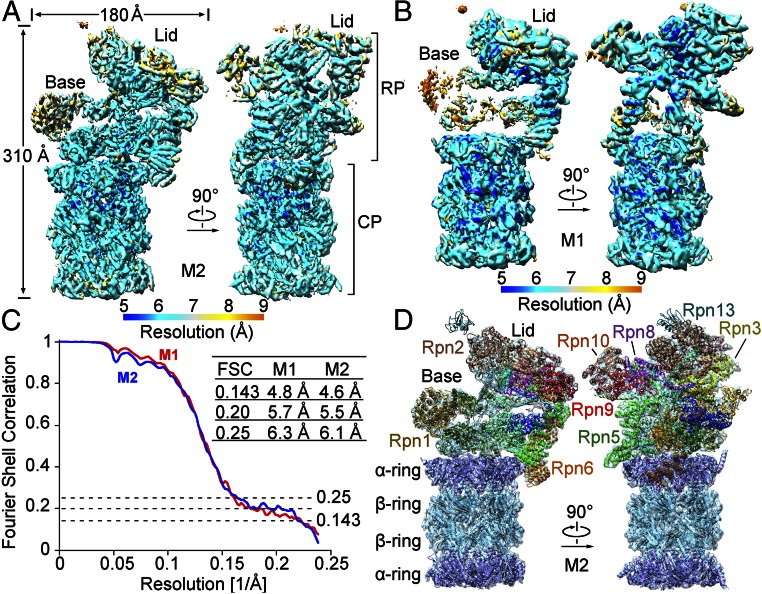

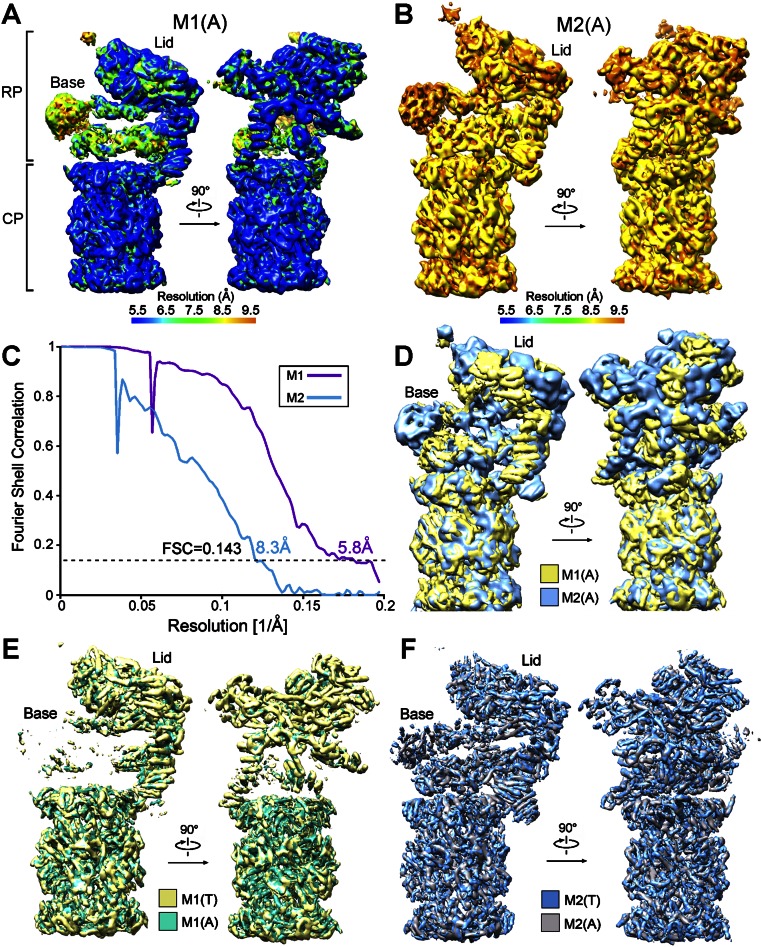

Fig. 1.

Cryo-EM structure of the S. cerevisiae proteasome. (A) Overall cryo-EM map of the proteasome from S. cerevisiae in the M2 conformational state. The average resolution is 4.6 and 6.1 Å on the basis of FSC values of 0.143 and 0.25, respectively. The range of resolution is color-coded below the maps. (B) Overall cryo-EM map of the proteasome in the M1 conformational state. The cryo-EM maps in the M1 state are poorer in the base than those in the M2 state. (C) FSC curves of the cryo-EM reconstructions. Depending on the FSC values chosen, the resolutions for these two structures range between 4.6 and 6.3 Å. (D) Overall structure of the proteasome. A near-complete model for the backbone was built to fit the cryo-EM maps. Structural images in Figs. 1, 3A, 4, and 5C were prepared using Chimera (33). Images in Figs. 2, 3 B–L, and 5B were made in PyMOL (35).

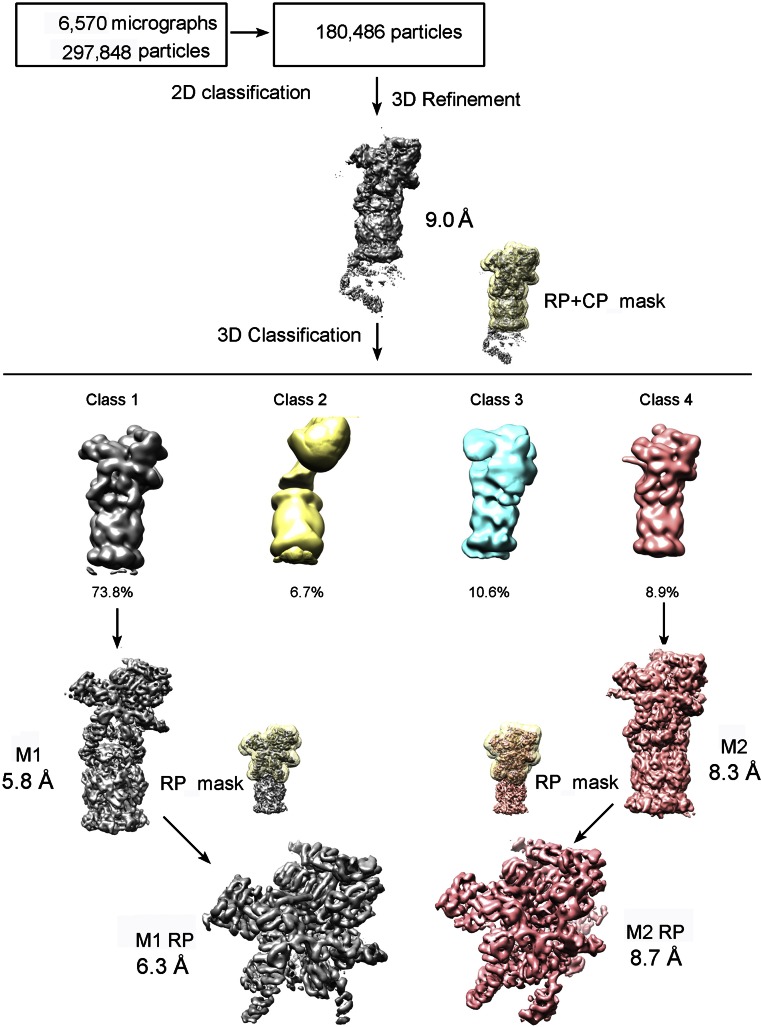

We also imaged the sample on a Tecnai Arctica microscope (Fig. S3); 133,198 particles from one class and 16,063 particles from another were autorefined to yield the M1 and M2 reconstructions with overall resolutions of 5.8 and 8.3 Å, respectively, on the basis of the FSC gold standard (Figs. S3 and S4 A–D). The M1 and M2 structures determined on the Tecnai Arctica microscope exhibit features nearly identical to those on the Titan Krios (Fig. S4 E and F). For simplicity, we focus our discussion on the structures derived from the Titan Krios.

Fig. S3.

Flow chart for the Tecnai Arctica cryo-EM data processing of the yeast proteasome; 297,848 particles were subjected to 2D classification and subsequent 3D refinement, producing a reconstruction at an average resolution of 9.0 Å. A large mask covering the CP and one RP was applied to 3D classification; 73.8% of all of the remaining particles were used to calculate the M1 conformation, and 8.9% of the particles gave rise to the M2 conformation. Next, a mask covering only one RP was applied to 3D classification, aiming to improve the quality of local density. After 3D refinement, cryo-EM maps of the RP at 6.3- and 8.7-Å resolution were generated for the M1 and M2 conformations, respectively. Please refer to SI Materials and Methods for details.

Fig. S4.

Comparison of the cryo-EM maps from datasets collected on different microscopes. (A) The overall cryo-EM density map of the proteasome from S. cerevisiae in the M1 state. The micrographs that give rise to this structure were collected on an FEI Tecnai Arctica electron microscope. The range of resolution is color-coded, with the bar shown below the maps. (B) The overall cryo-EM density map of the proteasome in the M2 state. Similar to that in A, this structure was calculated using data collected on the FEI Tecnai Arctica microscope. (C) The overall resolutions of the M1 and M2 states are estimated to be 5.8 and 8.3 Å, respectively, on the basis of the gold-standard FSC criteria of 0.143. (D) Overlay of the cryo-EM maps between the M1 and M2 states. Apparent differences are seen in the RP. (E) There are few differences between the cryo-EM maps of the M1 conformation generated on Titan Krios and Tecnai Arctica microscopes. (F) There are few differences between the cryo-EM maps of the M2 conformation generated on Titan Krios and Tecnai Arctica microscopes.

Structure of the S. cerevisiae Proteasome.

The final cryo-EM maps of the proteasome exhibit clear overall features, with most secondary structural elements identifiable (Fig. 1 A and B). With one RP counted, the proteasome measures 310 Å in length and 180 Å across the RP at its widest point (Fig. 1A). For the M2 state, 12 Rpn and 6 Rpt subunits exhibit decent cryo-EM density and can be unambiguously assigned (Figs. S5 and S6). The only exception is the distally located Ub receptor Rpn13, which displays poor EM density (Fig. 1 A and D). A large cavity is created between the lid and the Rpt subunits, with Rpn1 on the side (Fig. 1D and Fig. S6A). Compared with reported structures (8, 13, 15, 17), the cryo-EM map of the M2 state exhibits improved overall and local features. The Rpn subunits in the lid, Rpn1, and Rpt subunits display improved features for the α-helices (Fig. S7). A coiled-coil of two α-helices between Rpt1 and Rpt2 in our structure, as opposed to a single α-helix from Rpt1 (17), is found to directly bind Rpn1 (Fig. S7C). A near-complete model of the Cα trace was built for the M2 state (Fig. 1D and Table S1). The general features are similar to those reported previously (8, 13, 15, 17).

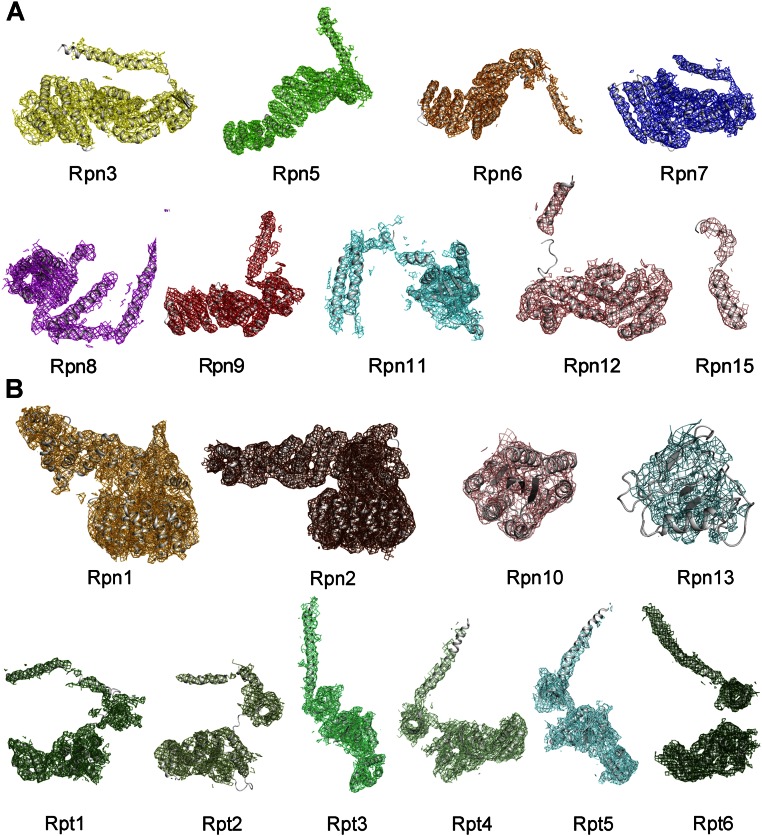

Fig. S5.

Cryo-EM density maps of the 19 subunits in the RP of the S. cerevisiae 26S proteasome in the M2 conformational state. (A) Cryo-EM density maps of the nine Rpn subunits in the lid. These are Rpn3, Rpn5, Rpn6, Rpn7, Rpn8, Rpn9, Rpn11, Rpn12, and Rpn15. (B) Cryo-EM density maps of the three Rpn and six Rpt subunits in the base and Rpn10. These include Rpn1, Rpn2, Rpn10, Rpn13, and Rpt1–6. The cryo-EM density allows unambiguous identification of all subunits except Rpn13. This figure was prepared using PyMOL (35).

Fig. S6.

Cryo-EM density map of the RP. (A) The cryo-EM density map of the RP is shown in two perpendicular views. Cryo-EM maps for the 19 subunits are color-coded. (B) Cryo-EM map of the Rpt ring in three views. (C) Cryo-EM map of the single α-ring and double-layered β-rings. Two perpendicular views are shown.

Fig. S7.

Comparison of the cryo-EM density maps for select regions of the 26S proteasome. (A) Comparison of the cryo-EM maps in the lid between the M2 conformation of our structure and the S1 conformation reported previously (17). Two views are shown. (B) Comparison of the cryo-EM maps in the Rpt ring between the M2 conformation of our structure and the S1 conformation reported previously (17). Two views are shown. (C) Comparison of the cryo-EM maps in the Rpt1/Rpt2/Rpn1 region between the M2 conformation of our structure and the S1 conformation reported previously (17). The coiled-coil is highlighted within the red circles.

Table S1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Data collection | |

| EM equipment | FEI Titan Krios |

| Voltage, kV | 300 |

| Detector | Falcon II |

| Pixel size, Å | 1.05 |

| Electron dose, e−/Å2 | 39.04 |

| Defocus range, μm | 1.5∼2.5 |

| Reconstruction (M1/M2) | |

| Software | RELION 1.4 |

| No. of used particles | 81,782/25,151 |

| Symmetry | C1 |

| Final resolution, Å | 4.8/4.6 |

| Map-sharpening B factor, Å2 | −186.6/−166.1 |

| Refinement (M1/M2) | |

| Software | PHENIX 1.10 |

| Model composition | |

| Protein residues | 13,329/13,366 |

| Rms deviations | |

| Bond length, Å | 0.003/0.003 |

| Bond angle, ° | 0.88/0.89 |

| Ramachandran plot statistics, % | |

| Preferred | 91.6/91.7 |

| Allowed | 6.6/6.6 |

| Outlier | 1.8/1.7 |

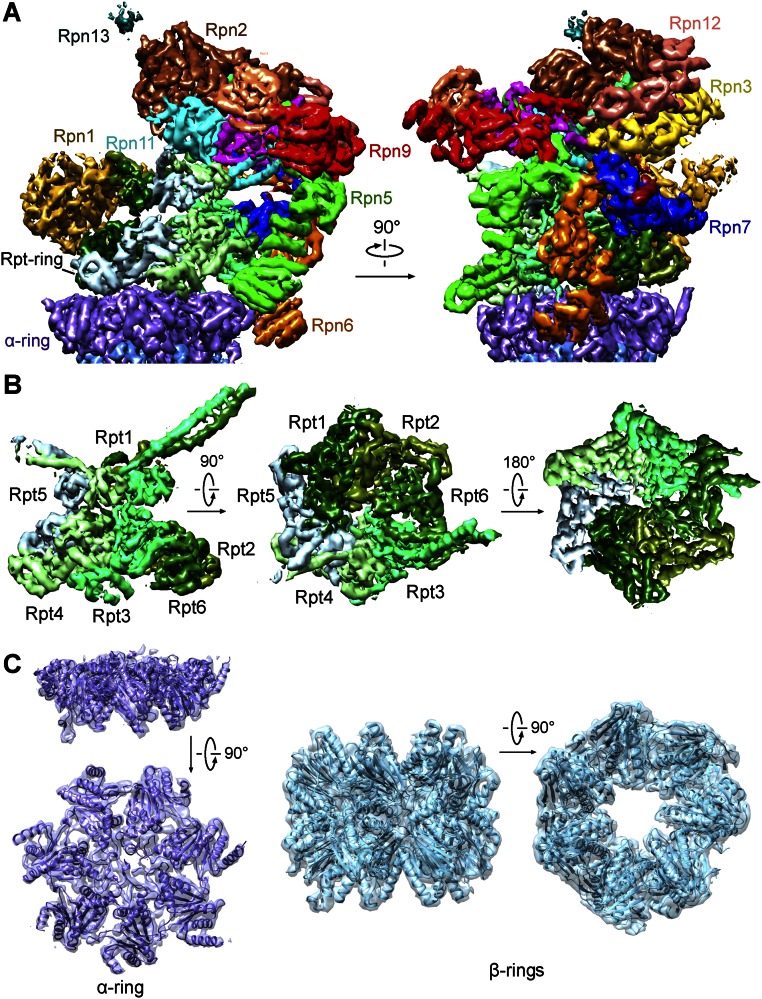

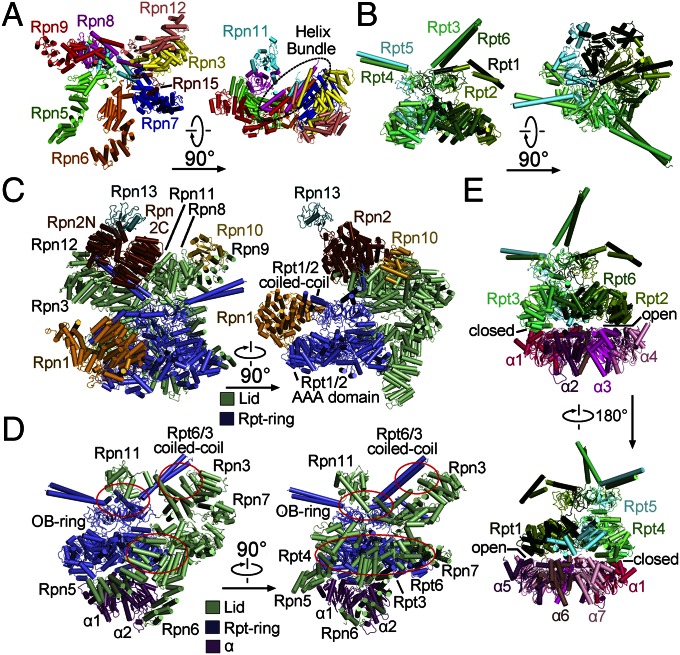

The lid resembles an open hand (Fig. 2A). The solenoid folds of Rpn3 and Rpn12 closely associate with each other, forming the thumb; the solenoid folds of the other four subunits Rpn7, Rpn6, Rpn5, and Rpn9 correspond to the index, middle, ring, and little fingers, respectively. The palm is formed by the PCI domains of these Rpn subunits. Notably, the N termini of these six Rpn subunits are placed at the tips of the five fingers, with their C-terminal α-helices forming two end-to-end stacked bundles in the palm (Fig. 2A). The intrinsic DUB Rpn11 interacts with Rpn8 above the palm, next to the C-terminal helix bundle. This arrangement places Rpn11 in the center of the lid yet makes it accessible to incoming poly-Ub chains (Fig. 2A and Fig. S6A). For the smallest proteasomal subunit Rpn15, only the C-terminal helix and an extended loop are assigned. The helix binds the solenoid of Rpn7, whereas the loop stretches toward Rpn3, suggesting an interaction between the N-terminal portion of Rpn15 and Rpn3 as predicted (19, 21).

Fig. 2.

Structural organization of the RP. (A) Overall structure of the lid. The open-hand structure of the lid is shown in two perpendicular views. The C-terminal helix bundle is highlighted by a dashed oval circle. (B) The two-layered structure of the Rpt ring. (C) The spatial arrangement of Rpn1, Rpn2, Rpn10, and Rpn13, relative to the lid (pale green) and the Rpt ring (slate). (D) Three discrete interfaces between the lid and the Rpt ring. The interfaces are identified by red ovals. (E) Asymmetric interactions between the hexameric Rpt ring and the heptameric CP ring. The loose and tight interactions between the Rpt ring and the α-ring are indicated as “open” and “closed,” respectively.

Each Rpt subunit sequentially consists of an N-terminal helical domain, oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding (OB) domain, and ATPase associated with diverse cellular activities (AAA) domain. The six Rpt subunits in the order of Rpt1-2-6-3-4-5 assemble into a two-layered structure, with six OB domains forming a small ring above the AAA ring (Fig. 2B). The N-terminal helical domains of these Rpt subunits form three coiled-coils: Rpt1/2, Rpt6/3, and Rpt4/5. The Rpt1/2 coiled-coil interacts with Rpn1, whereas Rpn1 lies at the edge of the Rpt ring and interacts with the AAA domains of Rpt1 and Rpt2 (Fig. 2C). The Rpt6/3 coiled-coil extends out to the C-terminal helical bundle of the lid and interacts with Rpn2, which is located at the top of the Rpt ring (Fig. 2C). Notably, the Rpt4/5 coiled-coil projects out in isolation and makes no contact with other subunits.

The lid directly contacts the Rpt ring through three discrete interfaces (Fig. 2D). One interface involves the N-terminal solenoids of Rpn5, Rpn6, and Rpn7, which interact with Rpt4, Rpt3, and Rpt6, respectively, on the periphery of the AAA ring. The solenoid fold of Rpn6 extends further to the CP, making close interactions with the α2-subunit; the solenoid fold of Rpn5 also directly contacts α1 (Fig. 2D). Another interface involves the MPN domain of Rpn11 and the OB ring in the center of the lid. The third interface is mediated by Rpn3 and the coiled-coil of Rpt6/Rpt3.

Although Rpn1, Rpn2, and Rpn13 are assigned to the base, they are spatially separated from each other (Fig. 2C). Rpn1 makes no contact with the lid or other Rpn subunits, providing an explanation for the highly flexible nature of Rpn1 within the proteasome. In addition to binding the coiled-coil of Rpt6/Rpt3, the N-terminal helices of Rpn2 contact Rpn3 and Rpn12 whereas its C-terminal helices interact with Rpn11. The N-terminal VWA domain of Rpn10 is located at the top edge of the RP, making contacts with Rpn8 and Rpn9. The ubiquitin-binding UIM of Rpn10 was invisible. Rpn13 only binds Rpn2 at the apical end of the proteasome.

In addition to Rpn6 binding to the α2-subunit, the RP is connected to the CP through asymmetric interactions between the hexameric Rpt ring and the heptameric CP ring (Fig. 2E). Specifically, the AAA domains of Rpt4 and Rpt5 closely stack against the α1/7- and α6/7-subunits, respectively. Compared with these close interactions, the Rpt2/6 end of the Rpt ring is slightly separated from the α-ring. The C-terminal tails of a subset of Rpt subunits are thought to bind the α-pockets at the interfaces between neighboring α-subunits. These interactions may anchor the RP to the CP as well as signal the opening of the CP gate. Unfortunately, there is little cryo-EM density for these Rpt C-terminal tails in our structure.

Comparison Between the M1 and M2 States.

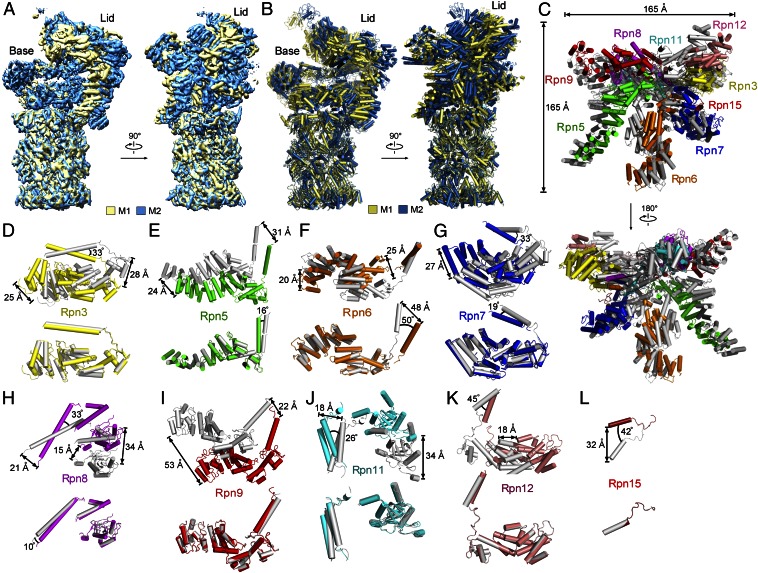

For the M1 state, the Rpn subunits are well-defined; however, the six Rpt subunits in the base exhibit discontinuous cryo-EM density (Fig. 1B), likely due to their dynamic conformational states associated with ATP binding and hydrolysis. Comparison of the cryo-EM maps between the M1 and M2 states reveals pronounced structural differences in the RP but not in the CP (Fig. 3A). The major differences reflect significant movement and rotation of most Rpn and Rpt subunits in the RP relative to the CP (Fig. 3B and Fig. S4D). The lid as a whole shows no obvious directionality in movement.

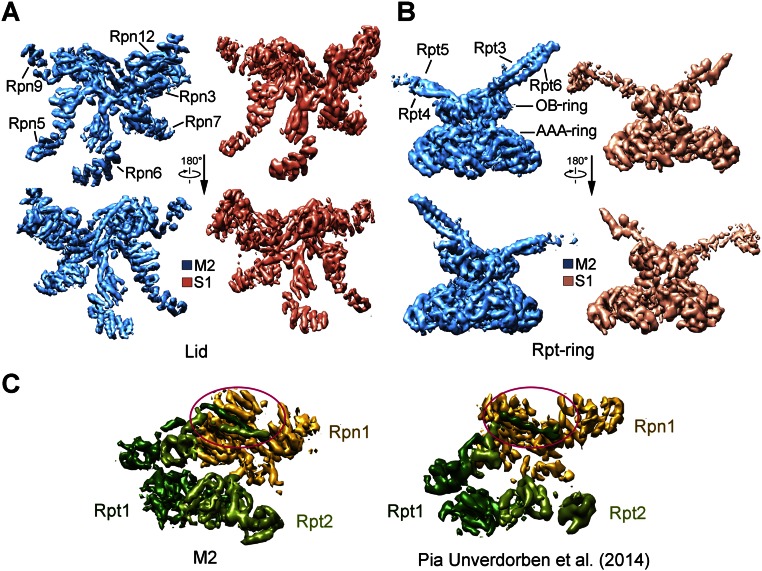

Fig. 3.

Structural comparison of the two conformational states. (A) Comparison of the cryo-EM maps between the M1 and M2 states. The cryo-EM maps are colored yellow and cyan for the M1 and M2 states, respectively. Relative to the CP, the RP displays pronounced conformational differences for the two states. (B) Comparison of the structural models between the M1 and M2 states. (C) Comparison of the lid in the two states. The Rpn subunits in the M1 and M2 states are shown in gray and coded by color, respectively. (D) Rpn3 in the two states exhibits large variations (Upper) but can be aligned to each other (Lower). The two structures of Rpn3 (Upper) are taken directly from C. The other eight Rpn subunits are similarly compared in E–L, with conformational variations (Upper) and aligned structures (Lower) shown. These eight Rpn subunits are Rpn5 (E), Rpn6 (F), Rpn7 (G), Rpn8 (H), Rpn9 (I), Rpn11 (J), Rpn12 (K), and Rpn15 (L).

In the lid, all nine Rpn subunits exhibit different conformations between the two states (Fig. 3C). Rpn3 subunits in the two states are related to each other by a 33° rigid-body rotation, resulting in separation of up to 25–28 Å at the periphery (Fig. 3D, Upper); these two subunits can be superimposed with a root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) of 0.44 Å (Fig. 3D, Lower). Rpn5 subunits in the two states, separated by 24–31 Å, can be aligned with an rmsd of 0.42 Å for 372 Cα atoms (Fig. 3E). The other seven Rpn subunits each displays a set of distinct structural differences (Fig. 3 F–L). Altogether, for five of the nine Rpn subunits (Rpn3/9/11/12/15), structures in the M1 and M2 states can be superimposed very well, suggesting rigid-body movement. For the other four subunits (Rpn5/6/7/8), such superposition brings the solenoid folds and PCI domains into good registry, but not the C-terminal helices (Fig. 3 E–H).

Comparison with Published Structures of the Proteasome.

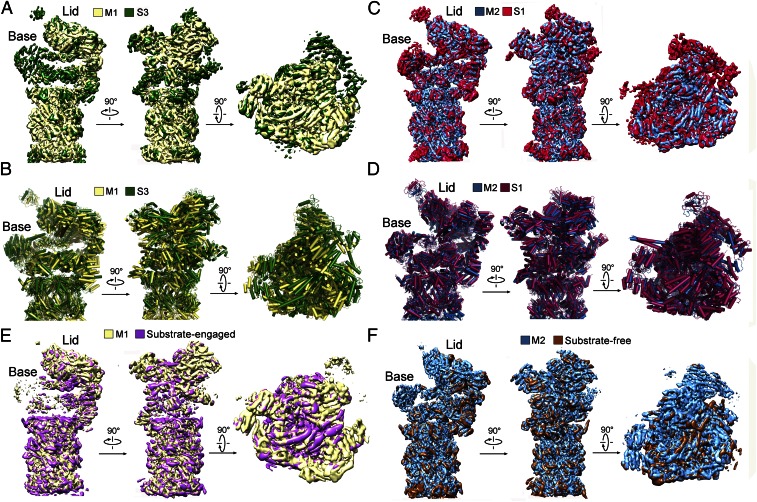

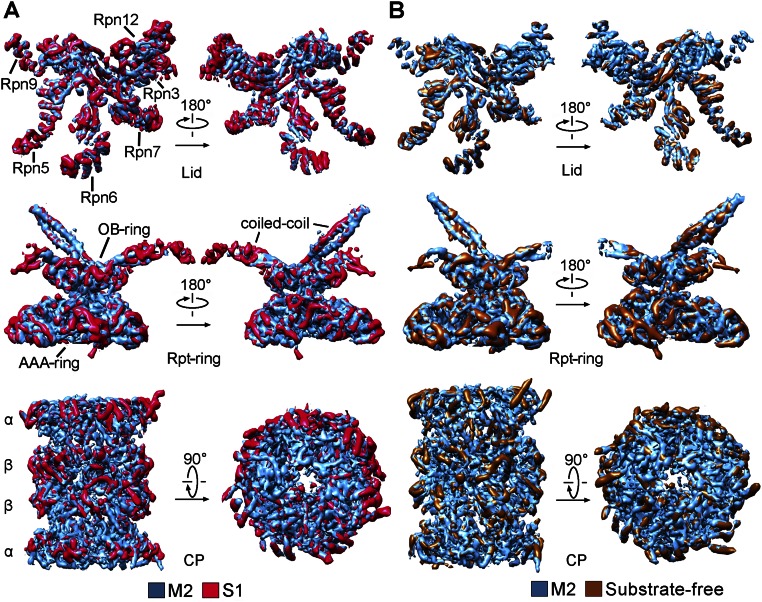

Comparison with published structures suggests that the M1 and M2 states may correspond to those of the proteasome determined in the presence of ATP-γS and ATP, respectively (17). The cryo-EM map of the M1 state exhibits similar structural features as those of the S3 state (17) (Fig. 4A). The majority of the secondary structural elements in the M1 state are aligned with those in the S3 state, with an overall rmsd of 2.02 Å (Fig. 4B). The cryo-EM map of the M2 state resembles that of the S1 state (Fig. 4C and Fig. S8A), which was determined in the presence of ATP (17); their backbone models are superimposed with an rmsd of 1.71 Å (Fig. 4D). Nonetheless, the overall resemblance applies to the individual subunits but not necessarily to every secondary structural element. The M1 and M2 states of the proteasome are also reminiscent of the substrate-engaged and substrate-free states, respectively (15) (Fig. 4 E and F and Fig. S8B). A direct inference from this analysis is that the presence of ATP-γS, or the absence of ATP hydrolysis, may correlate with substrate binding. This analysis suggests that mutational loss of ATPase activity, but not ATP binding, may facilitate substrate association, which can be experimentally tested.

Fig. 4.

M1 and M2 conformational states are similar to those reported earlier. (A) The M1 state is similar to the S3 state (17). Shown here is a comparison of the cryo-EM maps. (B) Structural overlay between the M1 and S3 states. (C) The M2 state is similar to the S1 state (17). Shown here is a comparison of the cryo-EM maps. (D) Structural overlay between the M2 and S1 states. (E) The M1 state is similar to the reported substrate-engaged state (15). (F) The M2 state is similar to the reported substrate-free state (15).

Fig. S8.

M2 conformation in our structure is very similar to the reported S1 and C2 conformations of the proteasome. (A) Comparison of the cryo-EM density maps between the M2 and the S1 conformations (17). The comparison, in two views, is shown for the lid (Top), Rpt ring (Middle), and CP (Bottom). (B) Comparison of the cryo-EM density maps between the M2 and the C2 conformations (15). The comparison is shown for the lid (Top), Rpt ring (Middle), and CP (Bottom).

Regulation of the DUB Activity of Rpn11.

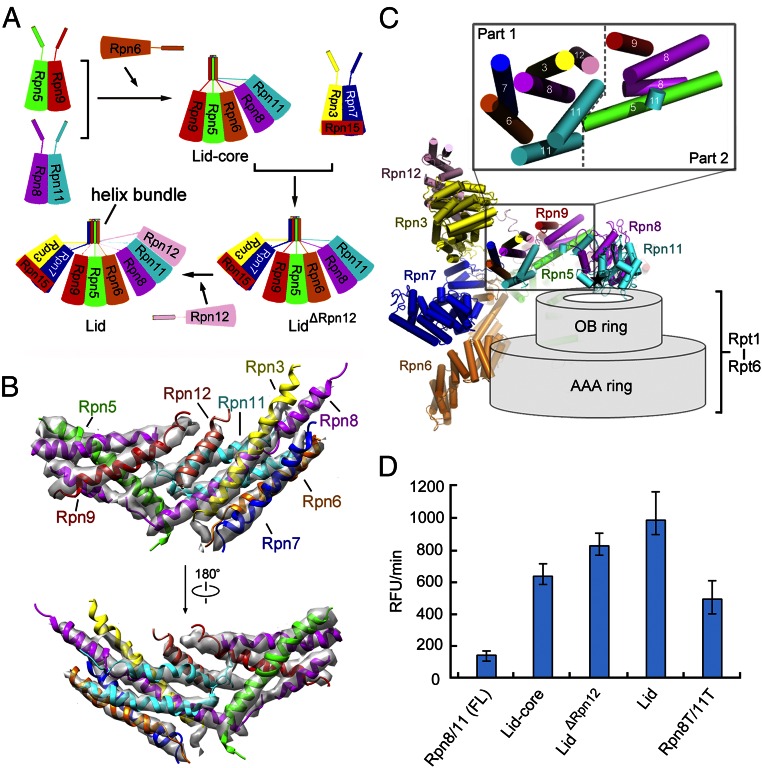

The RP recycles the poly-Ub chain through the intrinsic DUB activity of Rpn11 in the lid. Rpn8 is a catalytically inactive paralog of Rpn11 and forms a stable heterodimer with Rpn11 (22, 23) (Fig. 5A and Fig. S9A). Assembly of the lid is believed to occur in a hierarchical fashion (5, 24–26) (Fig. 5A), primarily driven by formation of the C-terminal helix bundle that includes domains from Rpn3/5/6/7/8/9/11/12 (4, 5). In our structure, the α-helices in the bundle are clearly defined (Fig. 5B), and the bundle is spatially divided into two stacked portions (Fig. 5 B and C). Part 1 contains seven α-helices from Rpn3/6/7/8/11/12, where two helices come from Rpn11. Part 2 consists of five α-helices from Rpn5/8/9/11, including two from Rpn8.

Fig. 5.

DUB activity of Rpn11 is markedly increased along with assembly of the lid. (A) A schematic diagram for the assembly of the lid. The C-terminal helices of the Rpn subunits are thought to facilitate the assembly by forming a helix bundle. (B) The cryo-EM maps of the C-terminal helix bundle in the lid. (C) Spatial arrangement of the Rpn subunits in the lid relative to the hexameric Rpt ring. A close-up view of the C-terminal helix bundle in the lid is shown. The catalytic site of Rpn11 is indicated by a black asterisk, which is positioned right above the pore of the OB ring. (D) The DUB activity of Rpn11 is markedly increased along with the assembly of the lid, as measured by cleavage of the fluorogenic substrate Ub-AMC. Rpn8T/11T denotes the heterodimer Rpn8 (residues 1–178)–Rpn11 (residues 1–239). SDs are calculated from three independent experiments. FL, full-length; RFU, relative fluorescence units.

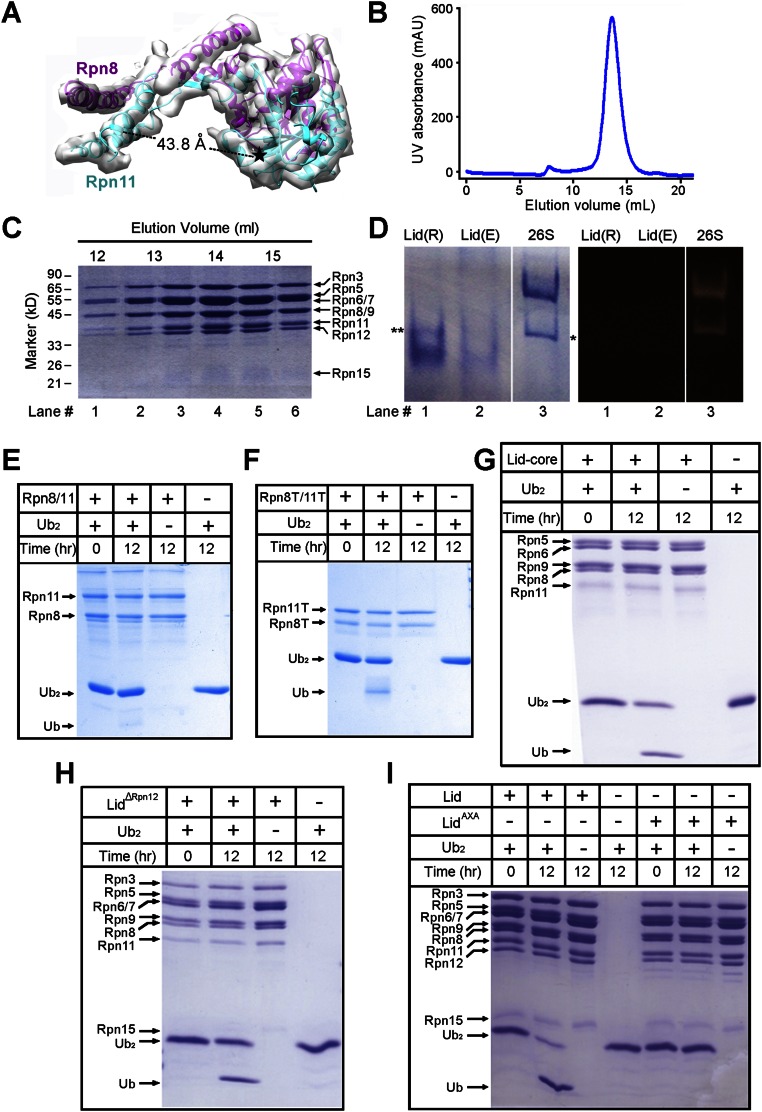

Fig. S9.

In vitro verification of DUB activity of recombinant lid subcomplexes by dissecting Lys48-Ub2. (A) The active site of Rpn11 (denoted by a black asterisk) is located ∼44 Å away from its C-terminal helices. A heterodimer between Rpn11 (cyan) and Rpn8 (magenta) is shown within the cryo-EM map. (B) Purification of the recombinant lid. A representative chromatogram of gel filtration (Superose 6) is shown for the purified recombinant lid. (C) Peak fractions of the recombinant lid from gel filtration were visualized by Coomassie blue on an SDS/PAGE gel. (D) Characterization of the recombinant lid. The purified recombinant lid (denoted by “R”) is visualized by native PAGE along with the endogenous lid (denoted by “E”) and the 26S proteasome (Left). The proteolytic activity of these complexes was examined using the fluorogenic peptide Suc-LLYV-AMC. Only the 26S proteasome, but not the lid, showed activity (Right). The 1:1 complex between the CP and RP is denoted by a single asterisk. A slow-migrating band, likely reflecting an aggregated form of the recombinant lid, is denoted by two asterisks. (E) Cleavage of Lys48-linked diubiquitin (Ub2) by the full-length Rpn8–Rpn11 complex. There was little cleavage activity. (F) Cleavage of Lys48-linked diubiquitin by the truncated Rpn8–Rpn11 complex (Rpn8T/Rpn11T). The cleavage activity was markedly improved over that of the full-length Rpn8–Rpn11 complex. (G) Cleavage of Lys48-linked diubiquitin by the core components of the lid (lid-core). Incubation of Ub2 with recombinant lid-core (Rpn5/6/8/9/11) resulted in the release of ubiquitin monomers. (H) Incubation of Ub2 with the Rpn12-deleted lid (lidΔRpn12) led to generation of ubiquitin monomers. (I) Incubation of Ub2 with the recombinant lid resulted in near-complete cleavage of the substrate. Mutation of the catalytic residues H109A/H111A in Rpn11 (lidAXA) abrogated the DUB activity of the lid.

The full-length Rpn8–11 dimer had little DUB activity, and truncation of the C-terminal sequences in Rpn8–11 led to marked elevation of the DUB activity (22, 23). In our structure, the active site of Rpn11 is separated from the C-terminal helices by a distance of ∼44 Å (Fig. S9A). Thus, the DUB activity of the lid is unlikely to be directly inhibited by the C-terminal helices in the assembled lid.

To examine the relationship between the DUB activity of Rpn11 and assembly of the lid, we expressed and purified five distinct Rpn11-containing complexes, including the full-length Rpn8–11, truncated Rpn8–11, core subunits of the lid (lid-core; Rpn5/6/8/9/11), lid without the subunit Rpn12 (lidΔRpn12), and lid (Fig. S9 B–D). These bacterially expressed complexes represent distinct stages of the lid formation. First, the DUB activity was qualitatively assessed using Lys48-linked diubiquitin (Lys48-Ub2) (Fig. S9 E–I). All Rpn8–11–containing complexes are able to cleave Lys48-Ub2, with the full-length Rpn8–11 complex displaying the lowest activity. The intact lid seems to be more active compared with lid-core or lidΔRpn12. Two missense mutations (H109A, H111A) were introduced into the catalytic residues to abolish the DUB activity of Rpn11, generating a catalytically inactive lid (lidAXA) (2, 3) (Fig. S9I).

Next, we reconstituted an in vitro assay using the fluorogenic substrate Ub-AMC. The full-length Rpn8–11 complex exhibits a basal-level DUB activity (Fig. 5D). This activity was enhanced by about fivefold for lid-core, sixfold for lidΔRpn12, and sevenfold for the intact lid. These results support the conclusion that the DUB activity increases along with the stepwise assembly of the lid. Consistent with published studies (22, 23), truncation of the C-terminal helices in Rpn8–11 also results in higher DUB activity, but this activity is lower than that of the lid-core (Fig. 5D). Thus, the increased DUB activity may be associated not just with the relief of steric hindrance from the C-terminal helices but also with assembly of the lid. Interactions with other Rpn subunits may bring activating conformational changes to Rpn11 or enhance substrate recruitment and targeting.

Discussion

In this study, we report the cryo-EM structures of the S. cerevisiae proteasome at resolutions of 4.6–6.3 Å. As anticipated, the cryo-EM density in the CP is generally better-resolved than that in the RP. Within the RP, the cryo-EM density in the lid is better-resolved over that in the base, especially the Rpt ring. This is likely caused by the heterogeneous conformation of the six Rpt subunits, each of which may exhibit three distinct states: ATP-bound, ADP-bound, and nucleotide-free. Combination of the various states among the six Rpt subunits generates a large number of conformations for the Rpt ring. Such heterogeneity may indirectly affect the Rpn subunits in the RP, thus hindering improvement of the overall resolution.

Data collected on two different microscopes both yielded two distinct conformational states of the proteasome. Intriguingly, the M1/M2 states correspond to those determined in the presence of ATP-γS/ATP (17) or in the presence/absence of exogenous substrate (15). Unlike the earlier studies, no ATP-γS or exogenous substrate was added to our sample preparation, and the Rpt and Rpn subunits contain no mutation. Only Rpn11 is N-terminally tagged with protein A, which is removed during proteasome purification. Our approach involves minimal alteration to the proteasomal subunits and ensures that the resulting proteasome is as native as possible. This analysis argues that the M1 and M2 states likely reflect physiologically populated conformations of the proteasome.

Despite obvious movement and rotation of individual Rpn/Rpt subunits in the RP between the M1 and M2 states, the distance between the two ubiquitin receptors Rpn10 and Rpn13 remains largely unchanged. This observation supports a conserved mode of poly-Ub chain recognition by the proteasome. The minimal number of Ubs in a poly-Ub chain for faithful recognition by the proteasome is four (27), and the space between Rpn10 and Rpn13 is thought to be appropriate for the accommodation of a tetra-Ub chain (8, 27, 28).

Few changes are seen in Rpn8 and Rpn11 when the structure of the C-terminally truncated Rpn8–11 complex (22, 23) is compared with that in the proteasome. Assuming that the structure of the assembled lid is the same as that in the proteasome, this observation indicates that the C-terminal helices of Rpn8 and Rpn11 indeed inhibit the DUB activity of Rpn11. This inhibition might be beneficial to cells, because it would avoid promiscuous deubiquitination before assembly of the lid. While this manuscript was under review, the cryo-EM structure of a recombinant lid at 3.5-Å resolution was published, which reveals fine features of nine Rpn subunits (29).

Materials and Methods

The S. cerevisiae strain sMK50 (30) was used for proteasome purification. The purified 26S proteasomes were imaged by an FEI Falcon II direct electron detector mounted on an FEI Titan Krios electron microscope operating at 300 kV and an FEI Tecnai Arctica electron microscope operating at 200 kV. Image processing was performed in RELION 1.4 (31). Model building and refinement were performed in Coot (32), Chimera (33), and PHENIX (34). The images of cryo-EM maps and models were prepared using Chimera (33) and PyMOL (35). The atomic coordinates of the M1 and M2 conformations of the yeast 26S proteasome have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under ID codes 3JCO and 3JCP, respectively. The cryo-EM maps have been deposited in the EMDataBank under accession nos. EMD-6574 through EMD-6579.

SI Materials and Methods

Endogenous Proteasome Purification.

The S. cerevisiae strain (sMK50) was derived from a previous study (30). Endogenous Rpn11 carries a protein A tag followed by a TEV protease cleavage site at its N terminus. The S. cerevisiae culture was grown in YPD medium at 30 °C for 24–36 h until OD600 reached ∼15. Cells from a 12-L culture were pelleted by centrifugation at 3,720 × g and resuspended in 100 mL buffer containing 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 2 mM ATP, and 5 mM MgCl2. The suspension, at a final volume of about 200 mL, was dropped into liquid nitrogen to form tiny beads with a diameter of 4–6 mm and pulverized to powder by a SPEX 6870 Freezer/Mill. Frozen cell powder was then resuspended in 100 mL buffer containing 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 2 mM ATP, and 5 mM MgCl2. The suspension was centrifuged at 27,000 × g at 4 °C for 1 h. The supernatant between the pellet and the white greasy layer was collected, yielding a volume of ∼200 mL, and incubated with 8 mL IgG Sepharose 6 Fast Flow resin (GE Healthcare) at 4 °C for 3 h. After extensive washing with buffer containing 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 2 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl2, and 100 mM NaCl, the resin was cleaved by TEV protease (with a His6 tag) at 18 °C for 2 h in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 2 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl2, and 100 mM NaCl. The eluent was loaded onto Ni-NTA affinity resin (QIAGEN) to remove the TEV protease. The proteasomal complex in the flow-through was then concentrated to 15 mg/mL using a centrifugal filter (Amicon Ultra), aliquoted, and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The same protocol was used for purification of the endogenous lid, except that the washing buffer contained 900 mM NaCl instead of 100 mM NaCl. This protocol is based on a previous study (20).

Recombinant Rpn11-Containing Complex Purification.

All components of Rpn8–11, Rpn8 (residues 1–178)–Rpn11 (residues 1–239), Rpn5/6/8/9/11, Rpn12-deleted lid (lidΔRpn12), lid, and lidAXA, each with a His6 tag and a GST tag, were cloned into the pQlink vector and coexpressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3). Templates used for cloning were originally from pGEX-2TK. The E. coli culture was grown in LB medium to OD600 1.0–1.5 at 37 °C and induced by 0.2 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) overnight at 22 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3,800 rpm for 10 min and resuspended in lysis buffer (25 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl) with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). Cells were lysed by sonication and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 27,000 × g at 4 °C for 1 h. The supernatant was loaded onto Ni-NTA affinity resin (QIAGEN) and the eluent was applied to GST affinity resin (GE Healthcare). After incubation with TEV protease at 18 °C for 3 h, the GST eluent was subjected to anion-exchange chromatography (SOURCE 15Q; GE Healthcare). The peak fractions were concentrated using a centrifugal filter (Amicon Ultra) and loaded onto a gel filtration column (Superdex 200 or Superose 6, 10/30; GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 25 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, and 5 mM DTT. The peak fractions were used for biochemical characterization.

Proteasome Substrate Cleavage Assay.

The proteolytic activity of the proteasome was monitored by cleavage of the fluorogenic peptide substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC (Bachem), following a published protocol (20). A 0.5-μL aliquot of purified endogenous proteasome (15 mg/mL) was analyzed on native PAGE at 4 °C. At the completion of electrophoresis, the gel was incubated in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 2 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 mM Suc-LLVY-AMC for 15 min at 37 °C. The reaction was quenched by removal of the buffer and soaking in ddH2O for 1 min. Fluorescence intensity of released AMC was measured by an ImageQuant 300 analyzer (GE Healthcare) at 365 nm. Finally, the native PAGE was stained by Coomassie blue.

Ub-AMC Cleavage Assay.

DUB activity was determined by cleavage of the fluorogenic substrate Ub-AMC. Ub-AMC was synthesized by covalently linking a Gly-AMC molecule (GSL) to the C terminus of purified Ub (residues 1–75). As a direct readout of the DUB activity, fluorescence reading of free AMC (λem 460 nm, λex 355 nm) was recorded, converted to relative fluorescence units (RFUs), and plotted as a function of time. The reaction was conducted at 30 °C in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mg/mL ovalbumin, 5 mM ATP/MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT. The final concentrations of DUB and Ub-AMC were 15 nM and 1 μM, respectively. Fluorescence intensity was recorded every 30 s within a 15-min period on a 384-well plate and with an EnVision microplate reader (PerkinElmer). Each experiment was independently repeated three times.

Lys48-Linked Diubiquitin Cleavage Assay.

Approximately 10 μM recombinant full-length Rpn8–Rpn11, truncated Rpn8–Rpn11 (Rpn8T–Rpn11T), lid-core, lidΔRpn12, lid, or lidAXA was incubated with 300 μM Lys48-Ub2 at 30 °C. The reaction was stopped after 12 h by mixing with SDS loading buffer, incubated at 95 °C for 5 min, and kept at room temperature until analysis by 15% SDS/PAGE. Lys48-Ub2 was synthesized as described (36).

Cryo-EM Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition.

Aliquots of 4 μL purified proteasome at a concentration of 15 mg/mL containing 0.01% Nonidet P-40 were applied to glow-discharged holey carbon grids (Quantifoil Cu R2.0/2.0, 200 mesh). Grids were blotted for 2 s and flash-frozen in liquid ethane cooled by liquid nitrogen with a Vitrobot Mark IV (FEI) at 100% humidity and 8 °C. Images were acquired on an FEI Tecnai Arctica electron microscope operating at 200 kV with a nominal magnification of 78,000× (or on an FEI Titan Krios microscope operating at 300 kV with a nominal magnification of 75,000×). Images were recorded manually using an FEI Falcon II direct electron detector and binned to a pixel size of 1.27 Å for Tecnai Arctica (or 1.05 Å for Titan Krios). Defocus values varied from 1.6 to 3.2 μm for Tecnai Arctica (or 1.5–2.5 μm for Titan Krios). For data collected on the Tecnai Arctica, each image was dose-fractionated to 21 frames with a dose rate of ∼27.9 counts per s per physical pixel (∼17.3 e− per second per Å2), total exposure time of 1.2 s, and 0.06 s per frame. For data collected on the Titan Krios, each image was dose-fractionated to 21 frames with a dose rate of ∼25.57 counts per s per physical pixel (∼23.19 e− per second per Å2), total exposure time of 1.6 s, and 0.08 s per frame.

Image Processing.

The 21 frames of each micrograph were aligned and summed using whole-image motion correction (37). Contrast transfer function parameters were estimated using CTFFIND3 (38). Templates for reference-based autopicking were generated from 2D class averages that were calculated from manually picked 3,000 particles from a subset of 100 micrographs. Particles were then autopicked by RELION 1.4 and manually checked by removing bad particles and adding previously missed particles. All 2D and 3D classifications and refinements were performed using RELION 1.4 (31).

For data collected on Tecnai Arctica/Titan Krios, a total of 297,848/183,626 particles from 6,570/5,517 micrographs were selected for reference-free 2D class averaging, and 180,486/166,564 particles from those classes that contain RPs were selected for an initial autorefinement. In both cases, a 40-Å low-pass–filtered cryo-EM reconstruction of the S. cerevisiae 26S proteasome (EMD accession no. 2165) was used as an initial model. This resulted in a reconstruction at an average resolution of 6.8 Å for Tecnai Arctica and 6.9 Å for Titan Krios. In both cases, the two RPs showed distinct map qualities, typically one good (RP1) and the other poor (RP2). This is consistent with the 2D average result because most particles contained one RP and only a small number of particles had two RPs. A 3D classification into four classes for the Tecnai Arctica data or five classes for the Titan Krios data was then performed for the refined particles. A mask around CP and RP1 was added during 3D classification. Among the four classes of the Tecnai Arctica data, class 1 and class 4 showed good overall reconstruction features and were individually subjected to autorefinement, resulting in two reconstructions at 5.8- and 8.3-Å resolution, respectively [gold-standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC) 0.143]. Comparison between the two maps reveals that the RP in these two reconstructions exists in different conformations and likely represents two different states of the proteasome (M1 and M2). To further improve the map quality, a soft mask around the RP was applied for another round of autorefinement. The overall resolution of the RP region was 6.3 Å for the M1 state and 8.7 Å for M2. Among the five classes of the Titan Krios data, class 2/class 3 and class 5 displayed good features and were autorefined, yielding two reconstructions at 4.8- and 4.6-Å resolution, respectively (FSC 0.143). These two reconstructions correspond to the M1 and M2 states from the Tecnai Arctica data. Reported resolutions were based on the FSC 0.143 criterion (39). Local resolution variations were estimated using ResMap (40).

In both cases, a cross-refinement was performed to check potential model bias. The 10-Å low-pass–filter map of the M2 state was used as the initial model for the refinement of the particles assigned to the M1 state. In both cases, the initial model did not influence convergence, and the resulting map was indistinguishable from the one obtained for the M1 state. It was the same case when a 10-Å low-pass–filter map of the M1 state was used as initial model for the refinement of the particles assigned to the M2 state. In addition, we tried multiple 3D classifications with different numbers of classes (three to six instead of four), different masks (including RP regions), and different initial models. In all cases, despite the differences in class distribution and structural details, the two conformational states were readily identified.

Model Building and Refinement.

Owing to varying resolutions for different regions of the proteasome, we combined model building and homologous structure docking to generate the structural model. The cryo-EM structure of the S. cerevisiae proteasome (PDB ID codes 4CR2 and 4CR4) (17) and the crystal structure of the S. cerevisiae 20S CP (PDB ID code 1RYP) (10) were docked into the two density maps. The initial models were manually adjusted in Coot (32), and a number of additional residues were modeled into the cryo-EM density maps. Rpn13, which is located in a poorly resolved part of the cryo-EM map, was modeled as a rigid body. Models of Rpt and Rpn1 were built mainly based on the cryo-EM map of the M2 state using the Titan Krios data, which exhibit better density at the base region, especially for Rpn1. The models were then rigidly fitted into the cryo-EM density map with UCSF Chimera (33). Finally, the coordinates of the two generated structures were refined in real space by PHENIX. real_space_refine (34) with secondary structure and geometry restraints to prevent overfitting. The final overall models were refined against the overall 4.6- and 4.8-Å maps using PHENIX.refine in reciprocal space with stereochemical and homology restraints.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Tsinghua University Branch of the China National Center for Protein Sciences (Beijing) for providing facility support. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 31321062 and 31430020 (to Y.S.), 31100524 (to Z.M.), and 31270764 (to F.W.), and NIH Grant R37-GM043601 (to D.J.F.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates of the M1 and M2 conformations have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 3JCO and 3JCP, respectively). The cryo-EM maps have been deposited in the EMDataBank, www.emdatabank.org (accession nos. EMD-6574 through EMD-6579).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1601561113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Finley D, Chen X, Walters KJ. Gates, channels, and switches: Elements of the proteasome machine. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41(1):77–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yao T, Cohen RE. A cryptic protease couples deubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome. Nature. 2002;419(6905):403–407. doi: 10.1038/nature01071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verma R, et al. Role of Rpn11 metalloprotease in deubiquitination and degradation by the 26S proteasome. Science. 2002;298(5593):611–615. doi: 10.1126/science.1075898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estrin E, Lopez-Blanco JR, Chacón P, Martin A. Formation of an intricate helical bundle dictates the assembly of the 26S proteasome lid. Structure. 2013;21(9):1624–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomko RJ, Jr, et al. A single α helix drives extensive remodeling of the proteasome lid and completion of regulatory particle assembly. Cell. 2015;163(2):432–444. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang F, et al. Structural insights into the regulatory particle of the proteasome from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii. Mol Cell. 2009;34(4):473–484. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang F, et al. Structure and mechanism of the hexameric MecA-ClpC molecular machine. Nature. 2011;471(7338):331–335. doi: 10.1038/nature09780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lander GC, et al. Complete subunit architecture of the proteasome regulatory particle. Nature. 2012;482(7384):186–191. doi: 10.1038/nature10774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Löwe J, et al. Crystal structure of the 20S proteasome from the archaeon T. acidophilum at 3.4 Å resolution. Science. 1995;268(5210):533–539. doi: 10.1126/science.7725097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groll M, et al. Structure of 20S proteasome from yeast at 2.4 Å resolution. Nature. 1997;386(6624):463–471. doi: 10.1038/386463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unno M, et al. The structure of the mammalian 20S proteasome at 2.75 Å resolution. Structure. 2002;10(5):609–618. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00748-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lasker K, et al. Molecular architecture of the 26S proteasome holocomplex determined by an integrative approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(5):1380–1387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120559109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck F, et al. Near-atomic resolution structural model of the yeast 26S proteasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(37):14870–14875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213333109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.da Fonseca PC, He J, Morris EP. Molecular model of the human 26S proteasome. Mol Cell. 2012;46(1):54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matyskiela ME, Lander GC, Martin A. Conformational switching of the 26S proteasome enables substrate degradation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20(7):781–788. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Śledź P, et al. Structure of the 26S proteasome with ATP-γS bound provides insights into the mechanism of nucleotide-dependent substrate translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(18):7264–7269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305782110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unverdorben P, et al. Deep classification of a large cryo-EM dataset defines the conformational landscape of the 26S proteasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(15):5544–5549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403409111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aufderheide A, et al. Structural characterization of the interaction of Ubp6 with the 26S proteasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(28):8626–8631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510449112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohn S, et al. Localization of the regulatory particle subunit Sem1 in the 26S proteasome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;435(2):250–254. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leggett DS, Glickman MH, Finley D. Purification of proteasomes, proteasome subcomplexes, and proteasome-associated proteins from budding yeast. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;301:57–70. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-895-1:057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomko RJ, Jr, Hochstrasser M. The intrinsically disordered Sem1 protein functions as a molecular tether during proteasome lid biogenesis. Mol Cell. 2014;53(3):433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pathare GR, et al. Crystal structure of the proteasomal deubiquitylation module Rpn8-Rpn11. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(8):2984–2989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400546111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Worden EJ, Padovani C, Martin A. Structure of the Rpn11-Rpn8 dimer reveals mechanisms of substrate deubiquitination during proteasomal degradation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21(3):220–227. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharon M, Taverner T, Ambroggio XI, Deshaies RJ, Robinson CV. Structural organization of the 19S proteasome lid: Insights from MS of intact complexes. PLoS Biol. 2006;4(8):e267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isono E, et al. The assembly pathway of the 19S regulatory particle of the yeast 26S proteasome. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(2):569–580. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-07-0635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukunaga K, Kudo T, Toh-e A, Tanaka K, Saeki Y. Dissection of the assembly pathway of the proteasome lid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396(4):1048–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thrower JS, Hoffman L, Rechsteiner M, Pickart CM. Recognition of the polyubiquitin proteolytic signal. EMBO J. 2000;19(1):94–102. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakata E, et al. Localization of the proteasomal ubiquitin receptors Rpn10 and Rpn13 by electron cryomicroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(5):1479–1484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119394109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dambacher CM, Worden EJ, Herzik MA, Jr, Martin A, Lander GC. Atomic structure of the 26S proteasome lid reveals the mechanism of deubiquitinase inhibition. eLife. 2016;5:e13027. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleijnen MF, et al. Stability of the proteasome can be regulated allosterically through engagement of its proteolytic active sites. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14(12):1180–1188. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scheres SH. RELION: Implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J Struct Biol. 2012;180(3):519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(Pt 12 Pt 1):2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: Building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58(Pt 11):1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeLano WL. 2002 The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. Available at www.pymol.org.

- 36.Dong KC, et al. Preparation of distinct ubiquitin chain reagents of high purity and yield. Structure. 2011;19(8):1053–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li X, et al. Electron counting and beam-induced motion correction enable near-atomic-resolution single-particle cryo-EM. Nat Methods. 2013;10(6):584–590. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mindell JA, Grigorieff N. Accurate determination of local defocus and specimen tilt in electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2003;142(3):334–347. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(03)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen S, et al. High-resolution noise substitution to measure overfitting and validate resolution in 3D structure determination by single particle electron cryomicroscopy. Ultramicroscopy. 2013;135:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kucukelbir A, Sigworth FJ, Tagare HD. Quantifying the local resolution of cryo-EM density maps. Nat Methods. 2014;11(1):63–65. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]