Abstract

Thiazolidinedione drugs (TZDs) such as pioglitazone are FDA-approved for the treatment of insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes. However, whether TZDs reduce painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN) remains unknown. Therefore we tested the hypothesis that chronic administration of pioglitazone would reduce PDN in Zucker Diabetic Fatty (ZDFfa/fa) rats. Compared to Zucker Lean (ZLfa/+) controls, ZDF developed: (1) elevated blood glucose, HbA1c, methylglyoxal and insulin; (2) mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia at the hindpaw; (3) increased avoidance of noxious mechanical probes in a mechanical conflict avoidance behavioral assay, the first report of a measure of affective-motivational pain-like behavior in ZDF; and (4) exaggerated lumbar dorsal horn immunohistochemical expression of pressure-evoked phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (pERK). Seven weeks of pioglitazone (30 mg · kg−1 · d−1 in food) reduced blood glucose, HbA1c, hyperalgesia, and pERK expression in ZDF. This is the first report to reveal hyperalgesia and spinal sensitization in the same ZDF animals, both evoked by a noxious mechanical stimulus that reflects pressure pain frequently associated with clinical PDN. As pioglitazone provides the combined benefit of reducing hyperglycemia, hyperalgesia, and central sensitization, we suggest that TZDs represent an attractive pharmacotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes-associated pain.

Keywords: ZDF, PPAR gamma, painful diabetic neuropathy, pain

Introduction

Approximately one-third of patients with diabetes experience pain 1, 17, 47, commonly referred to as painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN) 102. A majority of preclinical PDN studies focus on the streptozotocin (STZ) model of type 1 diabetes 8. However, 90% of diabetic patients are type 2 (World Health Organization), the prevalence of PDN is greater in patients with type 2 1, 100, and pain mechanisms in type 1 versus type 2 likely differ 39, 85–87. Therefore we chose to study a genetic model of type 2 PDN, the Zucker Diabetic Fatty (ZDFfa/fa) rat 13.

Hyperglycemia develops within 6–10 wks of age 6, 13, 49, 92 in ZDF but not Zucker Lean (ZLfa/+) controls, and is followed by behavioral correlates of PDN, including hypersensitivity to mechanical 6, 25, 69, 78, 92, 101, 112 and thermal 25, 49, 78, 80 somatosensory stimulation. However, conflicting studies report either hypoalgesia 89, 92 or hyperalgesia 78, 112 in similarly aged ZDF. This raises concerns regarding examination of sensory thresholds at just a single age without regard to the developmental stage of diabetes 6, 49, 78, 89, 112, or omission of ZL controls when multiple ages are assessed 69. These deficiencies in the literature led us to rigorously evaluate multiple pain-like behaviors in ZDF and ZL at various ages in a well-controlled study.

We hypothesized that spinal cord plasticity contributes to pain in type 2 diabetes because: (1) hyperalgesic db/db mice exhibit dorsal horn increases in both phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (pERK) 16, 109, a marker of nociresponsive neuron activation 26 in the spinal dorsal horn 37, 63, 114, and the astrocyte activation marker GFAP 16, 52, 77, 109; (2) intrathecal injection of either the ERK phosphorylation inhibitor U0216109 or the astrocyte toxin L-α-aminoadipate 52 reverses hyperalgesia; and (3) augmented NMDA and AMPA receptor expression and function in the spinal cord 50 may contribute to hyperalgesia in ob/ob mice 44. A recent report indicated that spinal neurons in ZDF exhibit central sensitization in response to non-noxious hindpaw stimulation 87. However, concurrent evaluation of pain-like behavior was not performed. We go beyond these studies by evaluating spinal plasticity in PDN using a clinically relevant noxious pressure stimulus to evoke not only expression of pERK in the spinal dorsal horn but also behavioral hyperalgesia in the same subjects.

Thiazolidinedione drugs (TZDs) such as pioglitazone (Actos®) are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. TZDs also reduce the molecular and behavioral sequelae of neurological disease 22, 40, as well as neuropathic pain associated with brain 84, 111, spinal cord 58, 71 or nerve 11, 30, 55, 63, 96 injury. For example, we recently reported that pioglitazone reduced hypersensitivity to non-noxious mechanical stimulation in rats with traumatic nerve injury 63. However, it still remains unclear whether TZDs reduce the neuropathic pain associated with type 2 diabetes 97. In addition, behavioral signs of PDN in rodents are more frequently associated with hypersensitivity to noxious, rather than non-noxious stimulation. To address these gaps, we tested the hypothesis that chronic administration of Actos® would prevent the development of noxious pressure-evoked hyperalgesia and spinal central sensitization in ZDF rats.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Experiments were carried out in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Kentucky (Approved Protocol # 2009–0429). All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering, to reduce the number of animals used, and to utilize alternatives to in vivo techniques, in accordance with the International Association for the Study of Pain 115 and the National Institutes of Health Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Male ZL and ZDF rats (http://www.criver.com/products-services/basic-research/find-a-model/zucker-diabetic-fatty-(zdf)-rat, Charles River, Wilmington, MA) aged 4–19 weeks were used for all experiments. “Obese” ZDF rats are homozygous for the loss-of-function “fatty” mutation in the leptin receptor (fa/fa) that results in the development of type 2 diabetes 13. “Lean” ZL rats are heterozygous (fa/+), do not develop a diabetic phenotype, and are genetic controls for ZDF. All rats were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room on a 12 hour light – 12 hour dark cycle with lights on from 7:00am to 7:00pm. Prior to any behavioral or dietary manipulations, all rats were provided water and Formulab 5008 (TestDiets, Purina Mills, Richmond, IN) chow ad libitum. Formulab 5008 (formerly Purina 5008) food yields reliable diabetic symptoms including hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, impaired glucose tolerance and insulin insensitivity as reported by Charles River.

Measurement of Blood Glucose & HbA1c

Blood was collected at sacrifice for the measurement of MG-AGE and insulin at 19 wks of age in the Characterization of PDN study, and for the measurement HbA1c both before (12 wks) and after (19 wks) drug treatment in the Pioglitazone Administration study. Blood glucose was measured at weekly intervals in both studies. The experimental designs for these studies are described below.

Rats were lightly restrained in a towel and the distal tail wiped with an alcohol swab. A small nick was made at the distal tip of the tail using a #11 scalpel blade. Initial bleeding was wiped clean with gauze and subsequent drops of blood were either loaded into a room temperature HbA1c cartridge and analyzed using a DCA Vantage Analyzer (Siemens, Munich, Germany), or placed on a glucose test strip in triplicate and inserted into a glucose monitor (TrueTrack, Walgreens, Deerfield, IL). To avoid perturbations in pain-like behavior elicited by fasting or exogenous glucose administration in a tolerance test 18, 19, non-fasted blood glucose was measured. A random blood glucose level greater than 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) was defined as hyperglycemia81. We measured blood glucose at the same time each week to minimize circadian-induced fluctuations.

Pain-Like Behavior: Stimulus-Evoked

Fluctuations in noise, vibrations, temperature, and other distractors in the behavioral testing room were minimized to optimize reliable measurements between cohorts of animals tested during different behavioral sessions. To further reduce variability and acclimate animals to the different testing apparatuses, two weeks of training were performed prior to behavioral measures reported at 8 weeks of age.

Heat hyperalgesia was assessed by placing the animals on a heated surface (52.5 ± 1 °C) within an acr ylic enclosure (Hotplate; Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH). The time until a hindpaw withdraw response (e.g. jumping, licking, flicking) occurred was recorded. The animal was immediately removed after the withdraw response or at a cutoff of 30 s to avoid tissue injury. Three trials, with an inter-trial interval of at least 5 min, were averaged for each time point.

Mechanical hyperalgesia was measured using the Randall Selitto method 76 with slight modification to accommodate an electronic device with a force transducer (IITC Life Science Inc., Woodland Hills, CA). The thoracic body and head were lightly restrained in a towel with both hindpaws exposed. To start, one hindpaw was placed into the calipers with the blunted-point of the force transducer placed on the plantar surface between the 2nd and 3rd digits. The force exerted on the surface of the hindpaw by the blunted-point was gradually and uniformly increased until a withdraw reflex occurred. Animals were not required to vocalize. The gram force required to elicit a withdraw response was recorded. Because patients report increased responsiveness to repeated mechanical stimuli 70, we used multiple trials per time point to assess pressure hyperalgesia. The force until paw withdraw was measured three times for each hindpaw and then averaged together, as there was no significant difference in left versus right withdraw thresholds. The combined average of hindpaw withdraw thresholds is reported at each timepoint.

Cold hyperalgesia was assessed by placing the animal on a cooled surface (4°C ± 0.5°C) within an acrylic enclosure (Coldplate; IITC Life Science Inc., Woodland Hills, CA) for five minutes. The combined number of nociceptive responses (e.g. jumping, licking, flicking) for both hindpaws during the 5 min period is reported 36.

Pain-Like Behavior: Affective-Motivational

To assess the affective-motivational component of pain, we utilized a novel Mechanical Conflict Avoidance System (MCS) 45. MCS gives animals the option to remain in a start chamber containing an aversive light stimulus or choose to cross a chamber containing an aversive mechanical stimulus in the form of height-adjustable, blunted probes. If animals chose to leave the light chamber and cross the probes in the stimulus chamber, they then had the option to enter a darkened reward chamber. MCS behavioral testing began at 17 wks of age and consisted of three stages: familiarization, training, and testing. The latency to exit the light chamber was used as a measure of avoidance of the mechanical stimulus, and therefore a measure of affective-motivational pain-like behavior.

Familiarization – 1 day

Animals were placed in the light chamber with the light off; access to the stimulus chamber was restricted by a closed guillotine door. After 15 s of darkness, the light was turned on. After 20 s of light exposure, the guillotine door was raised and the animal was free to explore the entire apparatus, including the dark chamber, for 5 min. The animal was then returned to the homecage.

Training – 4 days

Animals were trained to move from the light chamber, through the stimulus chamber at a probe height of 0 mm (i.e. no probes), and into the dark chamber. Animals were placed in the light chamber with the light off; access to the stimulus chamber was restricted by a closed guillotine door. After 15 s of darkness, the light was turned on. After 20 s of light exposure, the guillotine door was raised and a timer started to measure the latency to exit the light chamber. If the animal did not exit the light chamber within 30 s, the guillotine door was closed and the animal was returned to its homecage. Upon entering the dark chamber, a second guillotine door was closed to restrict the animal to the dark chamber. Animals remained in the dark chamber for 45 s to reinforce the crossing of the stimulus chamber and then were returned to the homecage. Each animal underwent four training trials on each of the four training days.

Testing – 3 days

Assessment of the latency to exit in the presence of varying degrees of mechanical stimulus (1, 3, 4 mm) was initiated at 18 wks of age. Each testing day began with 1 trial in the absence of a stimulus (0 mm) followed by 3 trials with the probes raised to a predetermined height: 1 mm (d 1), 3 mm (d 2), 4 mm (d 3). The training procedure described above was also used for testing in either the absence (trial 1) or presence (trials 2–4) of mechanical probes in the stimulus chamber. Only one probe height was tested per day. Assessment at the 0 mm probe height was used to confirm that animals were still trained to cross the stimulus chamber.

Animals remained in their home cage for at least 10 min between training and testing trials. All four paws were required to leave the light chamber to determine the latency to exit. The average of 4 trials for each training day or 3 trials for each testing probe height is reported for each animal.

pERK Quantification via Immunohistochemistry

Upon general anesthesia with isoflurane (5% induction, 1.5% maintenance), the plantar surface between the 2nd and 3rd digits of the left hindpaw was stimulated with 110 g of constant force for 30 s per minute over a 5 min period. These stimulus parameters were chosen to mimic those used to elicit withdraw responses to noxious pressure as described above for mechanical hyperalgesia testing. Ten minutes after initiating pressure stimulation, animals were perfused through the left ventricle with 250 ml of room temperature 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with heparin (10,000 USP units/L) followed by 250 ml of ice-cold fixative (10% phosphate buffered formalin). The lumbar spinal cord was removed and post-fixed overnight in 10% phosphate buffered formalin and then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in 0.1 M PBS for several days. Transverse sections (30 μm) from L4-L5 were cut on a freezing microtome and collected in 0.1 M PBS. The sections were washed three times in 0.1 M PBS and then pretreated with blocking solution (3% normal goat serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 in 0.1 M PBS) for 1 h. Sections were then incubated in blocking solution containing the primary antibodies rabbit anti-pERK (1:250, #4370, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) and Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated mouse anti-NeuN (1:200, MAB377X, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) overnight at room temperature on a slow rocker in the dark. The sections were washed three times in 0.1M PBS, and incubated in goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:800, Alexa 568, Molecular Probes, Grand Island, NY) for 90 min, washed in 0.1M PBS, 0.01M PBS, then 0.01M PB, and non-sequentially mounted onto Superfrost Plus slides, air dried, and cover-slipped with Prolong Gold with DAPI mounting medium (Molecular Probes). 4–6 high quality sections were randomly selected for quantification.

All images were captured on a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-E microscope using a 10x objective and analyzed using NIS-Elements Advanced Research software. We focused our quantification of the number of pERK immunopositive cell profiles within lamina I-II, where the majority of C-fibers and nociceptive peripheral afferents terminate within the dorsal horn 4, 14. Colabeling of pERK with NeuN is expressed as the percentage of the total number of pERK profiles in laminae I-II also expressing NeuN. Each spinal cord slice was analyzed by an observer blinded to treatment. The average of n=5–6 animals per group is reported.

Quantification of Methylglyoxal-Derived Advanced Glycation End-Products (MG-AGEs)

MG-AGEs were quantified using a competitive ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (STA-811, Cell BioLabs, San Diego, CA). This ELISA uses a primary antibody that recognizes the hydroimidazolone (H1) moiety created by the modification of protein residues by methylglyoxal 2. Whole blood taken from the left ventricle prior to transcardial perfusions was collected in serum separator tubes (SST™, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and allowed to clot for 30 min. Clotted blood in SSTs was centrifuged at 5000 x g for 10 min at 4°C and the serum was transferred to fresh microcentrifuge tubes and stored at −80°C until MG-H1 ELISA analysis. Serum samples were diluted 1:2 in 0.1 M PBS to obtain concentrations in the span of the standard curve.

Insulin Quantification via ELISA

Non-fasted insulin levels were quantified by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (EMD Millipore; EZRMI-13K; Darmstadt, Germany) from serum obtained as described above in serum separator tubes (SST™, BD Biosciences) at time of sacrifice.

Pioglitazone Incorporation into Food

Actos® (pioglitazone hydrochloride; Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A., Inc., Deerfield, IL) was obtained from the University of Kentucky pharmacy in 30 mg tablets of 25% purity, and was incorporated into Formulab 5008 rat chow (TestDiets, Purina Mills, Richmond, IN). Average body weight and food consumption 83 were used to determine the concentration of Actos in chow required to achieve a dosing of 30 mg pioglitazone / kg body weight / day. For ZDFs the concentration of Actos in chow was 0.16% (catalog no. 5W01) and for ZLs the concentration was 0.207% (catalog no. 5W02). Food was provided ab libitum and consumption and body weights were monitored in order to calculate actual dosing.

Experimental Design: Characterization of PDN

To determine the time course of development of pain-like behavior, we monitored ZL and ZDF rats weekly from 4 to 18 weeks of age with n=12 per group. Weekly measurement of pain-like behaviors occurred on Monday thru Friday in the following order: coldplate, pressure, hotplate. Assessment of pain-like behaviors occurred prior to determination of blood glucose and mass at 2–4pm on Fridays. Animals were not fasted in order to minimize the potential effects of fasting on pain-like behavior. At least one day separated coldplate and hotplate determinations to avoid cross-modality sensitization. After behavioral and metabolic outcomes were assessed at 18 wks, the left hind paws of control and diabetic rats were stimulated, using the same pressure device used to determine behavioral hyperalgesia, in order to evoke pERK. Next, cardiac blood was taken prior to transcardial perfusion and fixation, and then tissues were harvested for subsequent assays.

Experimental Design: Pioglitazone Administration

Rats were divided into the following treatment groups using a 2×2 experimental design: ZL Vehicle (n=10), ZL Pioglitazone (n=10), ZDF Vehicle (n=10), ZDF Pioglitazone (n=9). Vehicle food was defined as unaltered Formulab 5008 chow.

Pain-like behaviors, blood glucose, and weight were measured weekly from 10 to 19 wks of age. HbA1c was measured at 12 and 19 wks. Vehicle or pioglitazone food treatment began after assessment of behavioral and metabolic outcomes at 12 wks and all further testing was performed by an observer blinded to drug treatment group. Food consumption was measured 3 times per week by calculating the mass difference between food added to the cage and food remaining in the cage then dividing by 2, as rats were housed in pairs, and the number of days that had lapsed between food additions. After outcome measurements were obtained during week 19, animals were pressure-stimulated to evoke pERK, perfused and fixed with buffered formalin for immunohistochemical analyses of spinal cords.

One rat from the ZDF Pioglitazone group was removed from all analyses prior to beginning pioglitazone administration due to an abnormally high baseline blood glucose level of 514 mg/dL (more than double all other animals). Because the phenotype for coldplate responses in ZDF was modest, we did not assess the effect of pioglitazone on cold hypersensitivity.

Statistical Analysis

Mass, glucose, hotplate, pressure, coldplate, and MCS were compared using a repeated measures two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparison correction. To compare ZL vs. ZDF, the outcome measures insulin, MG-AGE, HbA1c, and area-under-the-curve (AUC; calculated via the trapezoidal method) were analyzed using an unpaired, two-tailed t-test. To compare ZL vs. ZDF and vehicle vs. pioglitazone, the outcomes HbA1c and AUC were analyzed via a two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparison correction. Ipsilateral vs. contralateral or pioglitazone vs. vehicle comparisons of pERK immunohistochemistry in ZL vs. ZDF were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparison correction. A value of α=0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. All data were analyzed and graphed using Prism 6.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) and are presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

The ZDF Rat is a Model of Progressive Painful Diabetic Neuropathy

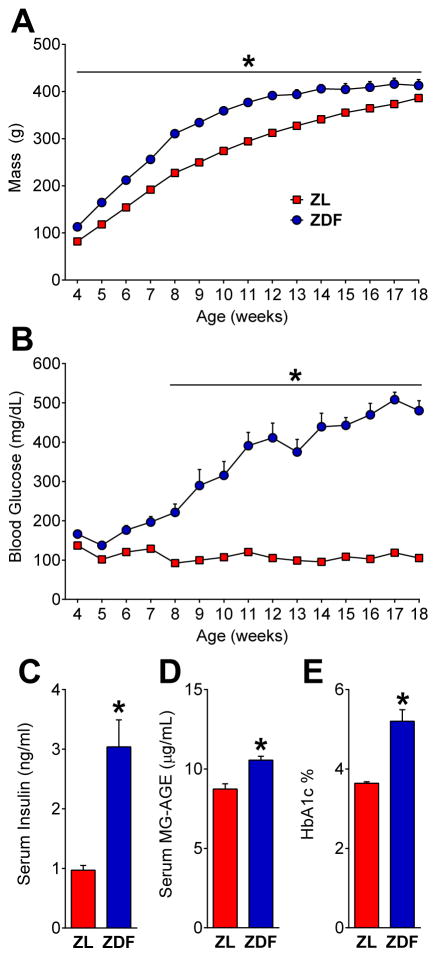

When compared to control heterozygotes or wild-types, only ZDF rats homozygous for the fatty (fa/fa) leptin receptor mutation develop cardinal symptoms of glucose-intolerant diabetes 13 including hyperphagia 69,83, hyperinsulinemia 51, 65, 92, obesity 69, hyperglycemia 69, 73, 101, elevated HbA1c 51, 92, and increased MG-AGE89. In the first experiment we characterized the progression of hyperglycemia and pain-like behavior in diabetic ZDF and control ZL rats. As illustrated in Figure 1A–C, ZDF had elevated mass [strain x time; F (14, 308) = 8.249; P < 0.0001] from 4 to 18 wks [p < 0.01], elevated blood glucose [strain x time; F (14, 308) = 46.31; P < 0.0001] from 8 to 18 wks [p < 0.0001], and elevated serum insulin [p = 0.0009] at 19 wks.

Fig. 1. ZDF rats develop a type 2 diabetes phenotype.

(A) Body mass (n=12) and (B) blood glucose levels (n=12), serum (C) insulin (n=6) at 19 wks, (D) methylglyoxal-derived advanced glycation end-products (MG-AGE; n=3) at 19 weeks and (E) HbA1c at 12 weeks of age (n=10) in Zucker Diabetic Fatty (ZDF) and Zucker Lean (ZL) controls. * p < 0.05, ZDF vs. ZL.

Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) such as methylglyoxal (MG) derived hydroimidazolone (MG-H1) are associated with diabetic pain in patients 93. MG-AGEs result from the accumulation of MG 35, a metabolite of glucose found in blood that is elevated in type 2 diabetes 41 and exacerbated in patients and mice with PDN 5. Therefore we measured MG-AGE levels and hemoglobin glycation in the form of HbA1c, an AGE considered by clinicians to be the ‘gold standard’ diagnostic for diabetes 81. Figure 1D indicates that 19 wk old ZDFs had elevated blood levels of MG-AGE [p < 0.05]. In a separate group of subjects, Figure 1E indicates that 12 wk-old ZDFs had elevated blood levels of HbA1c [p < 0.0001]. Thus, consistent with the literature, we found that ZDFs exhibited: (1) obesity after weaning that persisted until the conclusion of the study; (2) hyperglycemia beginning at 6 wks of age that progressively increased throughout the study; (3) hyperinsulinemia, elevated MG-AGE, and elevated HbA1c levels at 12 wks.

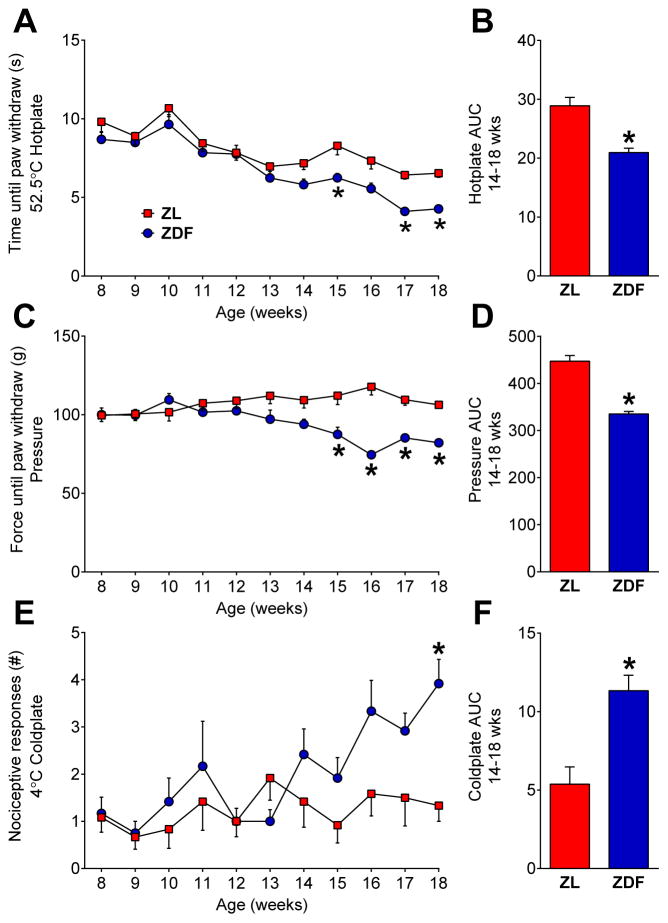

To rigorously evaluate the ZDF rat as a behavioral model of PDN, we measured not only evoked responses to noxious stimuli over an extended time course, but also signs of affective pain. First, to assess stimulus-evoked hyperalgesia, we measured responses to noxious mechanical and thermal stimuli. Figure 2A–B illustrates that ZDFs were hypersensitive to a noxious hotplate [strain; F (1, 22) = 14.2; P = 0.0011] at 15, 17, and 18 weeks of age [p < 0.05], exhibiting an overall decrease in heat response threshold from 14 to 18 wks [AUC; p < 0.05]. Figure 2C–D illustrates that ZDFs were hyperresponsive to noxious mechanical pressure [strain x time; F (10, 220) = 6.045; P < 0.0001] from 15 to 18 wks [p < 0.001], exhibiting an overall decrease in pressure threshold from 14 to 18 wks [AUC; p < 0.0001]. Figure 2E–F illustrates that ZDFs exhibited more hindpaw responses in a coldplate test [strain x time; F (10, 220) = 2.372; P = 0.0110] at 18 wks [p < 0.01], with an overall increase from 14 to 18 wks [AUC; p < 0.001].

Fig. 2. ZDF rats develop hyperalgesia.

Paw withdraw responses to (A–B) heat, (C–D) pressure, and (E–F) cold stimuli in ZL and ZDF rats. Area under the curve (AUC) analyses for 14–18 wks are shown. n=12 per group. * p < 0.05, ZDF vs. ZL.

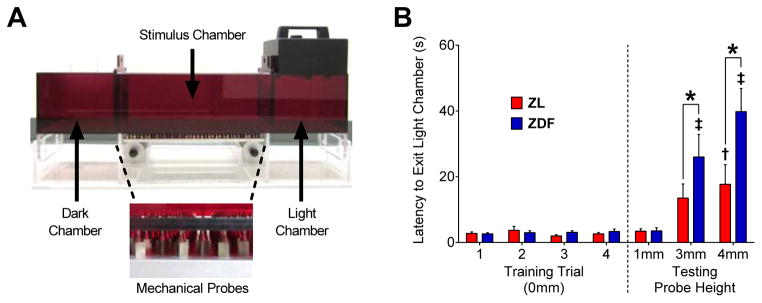

Preclinical research targeting the mechanisms of PDN primarily relies on stimulus-evoked behavioral outcomes 66. However, PDN symptoms include not just pressure and thermal hyperalgesia but also aching, paresthesia/dysesthesia, and affective pain 53. To our knowledge there are no reports of affective pain in a rodent model of type 2 diabetes 47. To address this gap and determine whether ZDFs possess the affective-motivational component of PDN that is most relevant to diabetic patients, we utilized a mechanical conflict-avoidance system (MCS) 20, 45, 64 as shown in Figure 3A. Figure 3B illustrates that illustrates that during the four training trials when no pins were present (0 mm probe height), latency to exit the light chamber was similar between ZL and ZDF rats (p > 0.05), indicating no differences in light aversion or learned motivation/ability to find the dark chamber. Despite contrasting results in an open field test, where we (unpublished findings; R.B. Griggs et al, 2013) and others 38 found diminished locomotor activity in ZDF, exploration in a novel open field environment is not equitable to behavioral training to seek the dark chamber in MCS. Raising the probe height produced an increase in the latency to exit the light chamber [strain x probe height; F (6, 102) = 4.262; P = 0.0007] in ZL at 4 mm (vs. 1 mm; p = 0.0051) and in ZDF at both 3 mm (p < 0.0001) and 4 mm (p < 0.0001) heights, indicating aversion to the mechanical stimulus in both control and diabetic rats. Importantly, the latency to exit the light chamber was higher in ZDF compared to ZL at both 3 mm (p = 0.0493) and 4 mm (p < 0.0001) heights, indicating that diabetes potentiates the avoidance of a noxious mechanical stimulus.

Fig. 3. Diabetes increases the avoidance of mechanical probes.

(A) Diagram of the mechanical conflict avoidance system (MCS) used as a measure of affective-motivational pain in ZL and ZDF rats. MCS behavioral testing began at 17 wks of age and consisted of three stages: familiarization (1 d), training (4 d), and testing (3 d). Familiarization: Animals were initially placed in the light chamber and allowed free access to explore the entire MCS apparatus. Training: Animals were trained to move from the light chamber, through the stimulus chamber with mechanical probes set to a height of 0 mm (i.e. no probes), and into the dark chamber. Each animal underwent four training trials on each of the four consecutive training days. Testing: Animals were placed in the light chamber and allowed to cross the stimulus chamber at probe heights of 1 mm, 3 mm, and 4 mm. Each animal was tested for 3 trials at each probe height with only one probe height tested on each of the three testing days. (B) The latency to exit the light chamber (latency) in ZL and ZDF rats is shown for the 4 d of training (left) and 3 d of testing (right). The latency was similar in the absence of mechanical probes (probe height = 0 mm) during training and at a 1 mm probe height during testing. Raising the testing probe height increased the latency in ZL at 3 mm and ZDF at 3 and 4 mm. The latency was greater in ZDFs compared to ZLs at the 3 and 4 mm probe height. n=9–10 per group. * p < 0.05. † p<0.05 vs. ZL at 1mm. ‡ p<0.05 vs. ZDF at 1 mm.

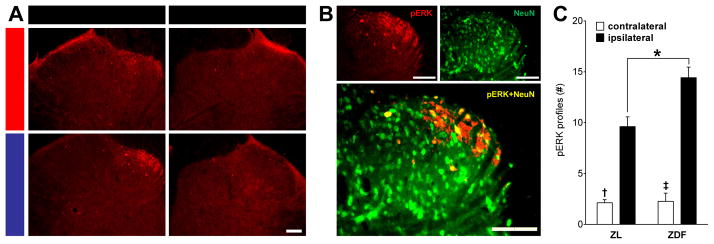

Central sensitization is defined as the increased responsiveness of nociceptive neurons in the central nervous system to their normal or subthreshold afferent input 107. As an example, expression of phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (pERK) in the dorsal horn is exacerbated by light touch stimulation after peripheral nerve injury 63 or inflammation 27 but not uninjured controls, and is therefore an important marker of spinal central sensitization 26. To test the hypothesis that diabetes results in central sensitization, we evaluated noxious pressure-evoked pERK expression in dorsal horn neurons. We chose pressure as the evoking stimulus because it is a hallmark pain modality in PDN patients 70. Figure 4A shows that unilateral stimulation of the tibial receptive field produced unilateral pERK expression within the superficial laminae of the dorsal horn. pERK was restricted to the side ipsilateral to stimulation and was predominantly located within the medial extent of the dorsal horn, respecting previously-described somatotopic boundaries of tibial nerve anatomy 14, 94. Figure 4B shows representative images indicating that pERK predominantly colabeled with NeuN, an established immunohistochemical marker for neurons 42. The percentage of pERK cell-profiles that colabeled with NeuN was (mean ± SEM): ZL contralateral (81.5 ± 6.5), ZL ipsilateral (88.3 ± 3.6), ZDF contralateral (80.5 ± 3.1), ZDF ipsilateral (92.1 ± 1.3). The degree of colocalization was similar between ZL and ZDF at either contralateral [p = 0.93] or ipsilateral [p = 0.89] dorsal horns. Figure 4C illustrates that pressure increased pERK in ZL [ipsilateral vs. contralateral; p < 0.0001] and ZDF rats [p < 0.0001]. Diabetes exacerbated this increase [ZDF vs. ZL; ipsilateral only; p = 0.001], and there was an interaction between Strain and Stimulation [F (1, 20) = 8.051; P = 0.0102].

Fig. 4. Diabetes exacerbates noxious pressure-induced activation of dorsal horn neurons.

Pressure-evoked pERK expression and colabeling with NeuN in the L4/5 dorsal horn at 18 wks of age in ZL and ZDF rats. Representative images of pERK (A) in the stimulated (ipsilateral) or unstimulated (contralateral) side and (B) colabeling with the neuronal marker NeuN in the medial portion of the ipsilateral lumbar dorsal horn after pressure stimulation. (C) Quantification of cell-like profiles labeled with pERK in laminae I-II. n=6 per group. † p<0.05 vs. ZL ipsilateral. ‡ p<0.05 vs. ZDF ipsilateral. * p<0.05. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Chronic Administration of Oral Pioglitazone Reduces Pathological Signs of Diabetes

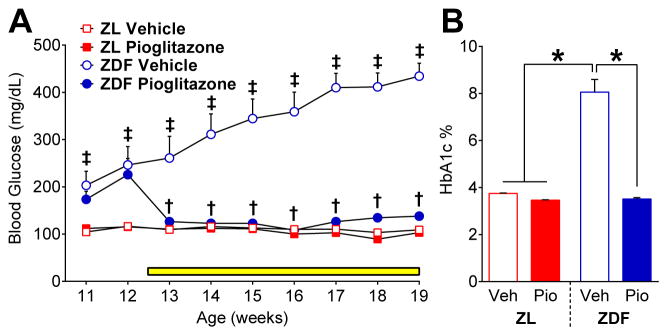

Numerous reports indicate that oral administration of pioglitazone or rosiglitazone reduces hyperglycemia in db/db mice 95, ZDF rats 73, and humans 3, 72, 108 as well as HbA1c levels in ZDF 105 and diet-induced type 2 diabetes 34. To confirm that pioglitazone alleviated signs of type 2 diabetes in ZDF, we measured blood glucose and HbA1c. The average dose of pioglitazone (mg · kg−1 · d−1) received by ZL (35.53 ± 1.94) and ZDF (32.19 ± 2.52) was similar over the 7 wk treatment period, and was comparable to previous studies in db/db mice (4 wks of 30 mg · kg−1 · d−1) 95 and ZDF rats (6 wks of 10 mg · kg−1 · d−1) 105. As illustrated in Figure 5A, pioglitazone decreased blood glucose in ZDF [F (1, 18) = 16.51; P = 0.0007] but not in ZLs [F (1, 18) = 3.51; P=0.077] from 13 to 19 wks of age. Figure 5B illustrates that blood levels of HbA1c were elevated in ZDF rats at 19 wks of age [p < 0.0001], even greater than observed at 12 wks (Fig 1E). Pioglitazone normalized HbA1c levels in ZDF to the level of ZL [p < 0.0001].

Fig. 5. Pioglitazone reduces pathological signs of type 2 diabetes.

Effect of vehicle or pioglitazone (administered in food, yellow bar) on blood levels of (A) glucose (n=9–10 per group) from 11 to 19 wks and (B) HbA1c (n=9–10 per group) at 19 wks of age in ZL and ZDF rats. ‡ p<0.05 vs. both ZL groups. † p<0.05, ZDF Pioglitazone vs. ZDF Vehicle. * p<0.05.

Chronic Oral Pioglitazone Inhibits the Development of PDN and Reduces Evoked pERK

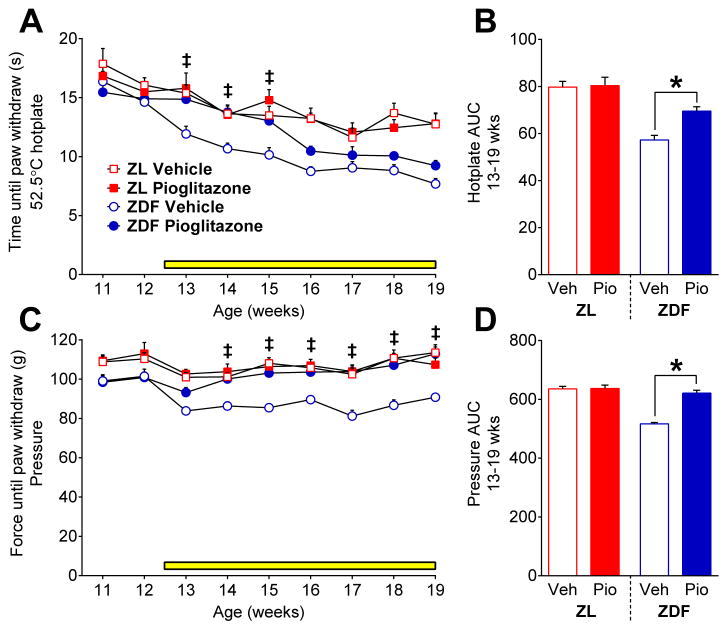

Hyperalgesia develops in ZDF at approximately 14 wks of age (Fig 2). To test the hypothesis that pioglitazone prevents the development of hyperalgesia, we initiated its administration at 12 wks of age. As illustrated in Figure 6A–B, ZDF exhibited lower heat response thresholds as compared to ZL [strain x time; F (8, 144) = 2.039; P = 0.0458] from 13 to 19 wks. Pioglitazone temporarily normalized heat thresholds in ZDF [F (1, 17) = 22.09; P = 0.0002] from 13 to 15 wks [p < 0.01], and then heat hypersensitivity returned at 16 wks. Figure 6C–D illustrates that ZDF exhibited a decrease in pressure response thresholds compared to ZL [strain x time; F (8, 144) = 2.178; P = 0.0324] from 11 to 19 wks [p < 0.05]. Pioglitazone normalized pressure thresholds in ZDF [drug; F (1, 17) = 104.9; P < 0.0001] throughout the duration of treatment, from 13 to 19 wks [p < 0.05]. Further studies are needed to investigate the differential effect of pioglitazone on heat and noxious mechanical sensitivity. In addition, we speculate that pioglitazone would reduce cold hypersensitivity as we recently reported that pioglitazone reduced the development of 63 and reversed 30 hyperresponsivitiy to acetone in the spared nerve injury model of neuropathic pain.

Fig. 6. Pioglitazone attenuates pain-like behavior.

Effect vehicle or pioglitazone in food (yellow bar) on the development of (A–B) heat and (C–D) mechanical hyperalgesia (n=9–10 per group). Pioglitazone inhibits the development of heat and mechanical hyperalgesia in ZDF. ‡ p<0.05 ZDF Vehicle vs. all other groups. * p<0.05.

Because we began pioglitazone administration prior to the development of hyperalgesia, further intervention studies are needed to determine if the mechanism of pioglitazone antihyperalgesia is independent from its reduction of hyperglycemia. This may indeed be the case, since we found that a single intraperitoneal injection of pioglitazone, given after the development of hyperalgesia in ZDF, reversed heat hypersensitivity without changing blood glucose levels (unpublished data, R.R. Donahue et al, 2014).

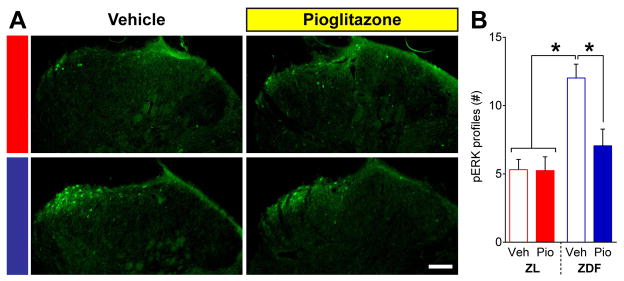

To determine whether chronic pioglitazone treatment reduces spinal nociresponsive neuron activation, we quantified pERK expression after noxious mechanical stimulation of the hindpaw. Figure 7A–B illustrates that noxious pressure evoked greater pERK in vehicle-treated ZDF as compared to ZL [p = 0.0006]. Pioglitazone but not vehicle normalized the expression of pERK in ZDF [p = 0.011] but not ZL [p = 0.96]. There was an interaction between Strain and Drug [F (1, 19) = 6.048; P = 0.0237].

Fig. 7. Pioglitazone attenuates dorsal horn neuron activation.

Noxious pressure-evoked expression of pERK in the lumbar superficial dorsal horn of ZL and ZDF rats at 19 wks of age following a 7 wk treatment with vehicle or pioglitazone administered in chow. (A) Representative images of pERK immunostaining. (B) Pioglitazone reduced pERK expression in ZDFs to the level of ZLs. n=5–6 per group. * p<0.05. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Discussion

ZDFs Develop Multiple Types of Pain-Like Behavior

Consistent with previous reports, ZDFs developed mechanical 6, 25, 49, 69, 78, 80, 92, 101, 112, heat 25, 49, 78, 80, and cold hyperalgesia 80 at 14 to 18 wks of age 25, 69, 101, results which we replicated in two separate cohorts. In contrast, a comparatively small number of ZDF studies report either mechanical hypoalgesia 89, heat hypoalgesia 89, 92, 101, no difference in heat 6 or pressure 73 response thresholds, and/or pressure hyperalgesia prior to hyperglycemia 79. Discrepancies in heat responses could be due to differences in the stimulus type: we used a hotplate while other studies used an infrared beam directed at the tail 92 or hindpaw 6, 89, 101.

A recent review of preclinical models of PDN highlights the need to establish indices of spontaneous/affective pain 47. One study used conditioned place preference (CPP), an assay that has re-emerged 91 as a leading preclinical measure of tonic pain in rats 43 and mice 32, to reveal affective pain in type 1 diabetic STZ mice in the absence of an evoking stimulus 103. Here, we discovered that type 2 diabetes exacerbates the avoidance of a noxious mechanical stimulus. Unlike CPP, where presumed relief of non-evoked affective pain reinforces a chamber preference, MCS utilizes the avoidance of an evoked stimulus as a measure of the motivational component of pain. Our results demonstrate for the first time the existence of a motivational-affective component of PDN in a preclinical model of type 2 diabetes.

ZDFs Develop Central Sensitization in Spinal Dorsal Horn Neurons

The dorsal horn is a key site of nociceptive integration 4 including central sensitization after tissue or nerve injury 107. A recent electrophysiological study in ZDF spinal cord slices indicated that non-noxious mechanical stimulation increased afterdischarges and spontaneous activity of dorsal horn neurons 87. However, the authors did not investigate pain-like behavior and they analyzed dorsal horn neurons at 32–34 wks, after ZDF aged 26 wks are reported to be hypoalgesic 47. Thus, at this advanced diabetic stage, it is unclear whether central sensitization contributed to painful diabetic neuropathy. In our study using younger ZDF, we resolved this uncertainty by evaluating both behavioral hypersensitivity and stimulus-evoked pERK in the same subjects.

We are the first to demonstrate both pain-like behavior and elevated spinal neuron activation in ZDF. Both of these results were observed in response to a noxious mechanical stimulus, and this fits with the clinical manifestations of PDN: up to 71% of patients 70 report hyperalgesia in response to application of a similar, static, noxious pressure stimulus 106 used in the current study on ZDF. By contrast, Schuelert et al reported that spinal neurons were not sensitized to noxious mechanical stimuli 87. Albeit, our results provide strong evidence in support of the hypothesis proposed by Schuelert et al that central sensitization contributes to hyperalgesia in type 2 diabetes 87. If true, then therapies aimed at reducing central sensitization could alleviate PDN. Indeed, spinal administration of MEK inhibitors, which prevent phosphorylation of ERK, attenuated hyperalgesia in db/db 109 and STZ 12 models.

Pioglitazone Reduces Pathological Signs of PDN in ZDF by Actions at PPARγ

Several lines of evidence lead us to speculate that activation of spinal peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) mediated the antihyperalgesic actions of pioglitazone reported here in ZDF. First, spinal sites are rich in PPARγ expression 11, 55, 61 and pioglitazone crosses the blood-brain barrier 56. Second, intrathecal administration of PPARγ antagonists inhibits the antihyperalgesic effect of both repeated systemic or single intrathecal administration of PPARγ agonists 11, 30, 63. Alternatively, non-PPARγ mechanisms can be proposed for the antihyperalgesic effects of pioglitazone in PDN. Pioglitazone inhibits HMGB1-RAGE signaling in spinal neurons 104 and reduces plasma RAGE 34, both of which are implicated in the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain in models of traumatic nerve injury 24 and PDN 33, 77. Whether pioglitazone reduces the contribution of spinal gliosis and/or HMGB1-RAGE signaling to PDN remains an important direction of future studies.

Our current results suggest that pioglitazone decreases central sensitization to reduce PDN in type 2 diabetes. In support of this idea, chronic oral pioglitazone (at the same 30 mg · kg−1 · d−1 dose used in the current study) reduced non-noxious stimulus-induced mechanical allodynia and spinal pERK in a traumatic nerve injury model of neuropathic pain 63. Our results extend this finding by showing that pioglitazone reduces spinal pERK following a different stimulus (noxious pressure) and in a different neuropathic pain model that is associated with disease (type 2 diabetes).

Our studies aimed to evaluate whether ZDF exhibited hyperalgesia alongside spinal sensitization and whether this could be reduced by a TZD, and therefore the focus was not on peripheral mechanisms. However, several studies suggest that pioglitazone can inhibit peripheral mechanisms of chronic pain: 1) PPARγ is expressed in sciatic nerve 110; 2) TZDs decreased hyperalgesia, proinflammatory cytokine expression, and macrophage infiltration in sciatic nerve after nerve injury 55, 96; 3) Pioglitazone reduced macrophage infiltration and pERK expression into the sciatic nerve of STZ rats 110; 4) Pioglitazone reduced pERK expression in sciatic nerve of db/db mice 15; and 5) Rosiglitazone and resolvin D1 coadministration to the site of hindpaw incision in db/db mice promotes a M2 macrophage phenotype and reduces mechanical hypersensitivity 82. Future studies in preclinical models of type 2 PDN could investigate the effect of local TZD administration to the peripheral nerve 31, 96 on: macrophage polarization 31; TNFα, which is elevated in patients with PDN 74, 99; nerve conduction velocity, which is decreased in type 2 diabetes 6; and pain-like behaviors.

Pioglitazone Reduces PDN Independent of its Anti-Hyperglycemic Action

Although we found that hyperglycemia preceded pain-like behavior as it does in type 2 diabetic patients 1, we propose that pioglitazone reduces PDN independent of its simultaneous reduction of blood glucose. This is based on several lines of evidence. First, pioglitazone and other PPARγ agonists reduce neuropathic pain-like behavior in normoglycemic animals after various routes of administration including: repeated oral 55, 63 or intraperitoneal 31, 55, 63, 96; local injection to the injured sciatic nerve 96 or incised paw 31; or a single spinal 11, 30, 62, 71 or brain 62 injection. Second, numerous drugs can reduce PDN without reducing hyperglycemia in patients with PDN, including tapentadol 88 or the FDA-approved PDN medications duloxetine and pregabalin 59, 90. Furthermore, the antioxidant taurine 49, aldose reductase inhibitors 9, 66, 75, insulin growth factor 112, 113, or poly-ADP-ribose inhibitors 21, 67, 68 reduce hyperalgesia in animal models of PDN without inhibiting hyperglycemia. Consistent with these findings, pioglitazone normalized peripheral nerve conduction velocities without affecting hyperglycemia in the STZ model 110. Third, mechanical hyperalgesia that is not associated with hyperglycemia has been reported in ZDFs, which suggests that hyperalgesia can be independent from blood glucose levels 79. Finally, it is important to note that normalization of blood glucose alone cannot reverse the neurotoxic effects resulting from long-term hyperglycemia 98 that contribute to PDN 102.

The results from this pretreatment study are clinically important as they suggest that pre-diabetic patients could benefit from adjuvant treatment with pioglitazone or an alternative PPARγ agonist in addition to recommended lifestyle changes such as diet and exercise. This is supported by preclinical studies indicating that TZD treatment prior to or coinciding with peripheral nerve injury are quite effective at reducing hyperalgesia 55, 63, 96. Further study is needed to definitively dissociate the antihyperglycemic and antihyperalgesic effects of targeting PPARγ with pioglitazone. For example, alternative agonists such as 15d-PGJ2 that alleviate neuropathic pain 11 without alteration of glucose or HbA1c could be tested in ZDF. Also, we could test a “control” drug that normalizes glucose metabolism without affecting hyperalgesia or investigate whether administration of glucose to pioglitazone-treated ZDF could reinstate hyperalgesia.

Conclusions and Future Directions

The current results are the first to demonstrate in a preclinical model of type 2 diabetes that pioglitazone prevents the development of not only pain-like behavior but also noxious stimulation-evoked central sensitization – within the same subjects. We go beyond the use of non-noxious von Frey hairs to evaluate spinal sensitization in ZDF 87 or nerve injury 63 by evoking spinal pERK and hyperalgesia using a clinically relevant pressure stimulus 70. Our results extend the potential efficacy of pioglitazone from resolving neuropathic pain after traumatic nerve injury to the growing problem of PDN.

Alternative strategies using other TZDs or related therapies may bypass the human safety risks of pioglitazone 48. First, the non-TZD PPARγ agonists FK614 60, MBX-102 10, 29, or MDG548 46 reduce insulin insensitivity, hyperglycemia, and inflammation and are neuroprotective 46. Second, TZDs 28, 111 or the novel ligand TT01001 95 reduce diabetic mitochondrial dysfunction by targeting the mitochondrial protein mitoNEET, which is thought to alleviate other neurological diseases 23, 111. Finally, a multiple drug strategy, such as coadministration of pioglitazone with canagliflozin 105 or geraniol 34 might reduce diabetes without the adverse effects of adipocyte differentiation, fat deposition, and weight gain associated with pioglitazone-only treatment. PDN patients may also benefit from other diabetic drugs such as metformin, which reduces peripheral neuropathic pain 57 and PDN in STZ rats 7, 54, as well as decreases hyperglycemia, HbA1c, and MG in patients with type 2 diabetes 41. Future clinical studies could investigate whether the above treatments or other PPARγ-directed therapies alleviate both hyperglycemia and neuropathic pain, as simultaneous inhibition is necessary to maximize quality of life in type 2 diabetic patients.

Perspective.

This is the first preclinical report to demonstrate that: 1) ZDF exhibit hyperalgesia and affective-motivational pain concurrent with central sensitization; and 2) Pioglitazone reduces both hyperalgesia and spinal sensitization to noxious mechanical stimulation within the same subjects. Further studies are needed to determine the anti-PDN effect of TZDs in humans.

Highlights.

The ZDF model of type 2 diabetes exhibits signs of motivational-affective pain

Central sensitization of dorsal horn neurons coincides with mechanical hyperalgesia

Pioglitazone inhibits hyperalgesia and central sensitization in type 2 diabetes

PPARγ-directed therapies may independently alleviate hyperglycemia and PDN

TZDs may be beneficial for patients presenting with both diabetes and chronic pain

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants 5R01NS062306 and R01NS045954 to BKT; T32NS077889 and F31NS083292 to RBG.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES:

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Abbott CA, Malik RA, van Ross ER, Kulkarni J, Boulton AJ. Prevalence and characteristics of painful diabetic neuropathy in a large community-based diabetic population in the U.K. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2220–2224. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed N. Methylglyoxal-Derived Hydroimidazolone Advanced Glycation End-Products of Human Lens Proteins. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2003;44:5287–5292. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronoff S, Rosenblatt S, Braithwaite S, Egan JW, Mathisen AL, Schneider RL. Pioglitazone hydrochloride monotherapy improves glycemic control in the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes: a 6-month randomized placebo-controlled dose-response study. The Pioglitazone 001 Study Group. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1605–1611. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.11.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basbaum AI, Bautista DM, Scherrer G, Julius D. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell. 2009;139:267–284. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bierhaus A, Fleming T, Stoyanov S, Leffler A, Babes A, Neacsu C, Sauer SK, Eberhardt M, Schnolzer M, Lasitschka F, Neuhuber WL, Kichko TI, Konrade I, Elvert R, Mier W, Pirags V, Lukic IK, Morcos M, Dehmer T, Rabbani N, Thornalley PJ, Edelstein D, Nau C, Forbes J, Humpert PM, Schwaninger M, Ziegler D, Stern DM, Cooper ME, Haberkorn U, Brownlee M, Reeh PW, Nawroth PP. Methylglyoxal modification of Nav1.8 facilitates nociceptive neuron firing and causes hyperalgesia in diabetic neuropathy. Nat Med. 2012;18:926–933. doi: 10.1038/nm.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brussee V, Guo G, Dong Y, Cheng C, Martinez JA, Smith D, Glazner GW, Fernyhough P, Zochodne DW. Distal Degenerative Sensory Neuropathy in a Long-Term Type 2 Diabetes Rat Model. Diabetes. 2008;57:1664–1673. doi: 10.2337/db07-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrne FM, Cheetham S, Vickers S, Chapman V. Characterisation of pain responses in the high fat diet/streptozotocin model of diabetes and the analgesic effects of antidiabetic treatments. Journal of diabetes research. 2015;2015:752481. doi: 10.1155/2015/752481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calcutt NA, Cooper ME, Kern TS, Schmidt AM. Therapies for hyperglycaemia-induced diabetic complications: from animal models to clinical trials. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:417–430. doi: 10.1038/nrd2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calcutt NA, Freshwater JD, Mizisin AP. Prevention of sensory disorders in diabetic Sprague-Dawley rats by aldose reductase inhibition or treatment with ciliary neurotrophic factor. Diabetologia. 2004;47:718–724. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandalia A, Clarke HJ, Clemens LE, Pandey B, Vicena V, Lee P, Lavan BE, Gregoire FM. MBX-102/JNJ39659100, a Novel Non-TZD Selective Partial PPAR-gamma Agonist Lowers Triglyceride Independently of PPAR-alpha Activation. PPAR Res. 2009;2009:706852. doi: 10.1155/2009/706852. Epub 702009 Apr 706823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Churi SB, Abdel-Aleem OS, Tumber KK, Scuderi-Porter H, Taylor BK. Intrathecal rosiglitazone acts at peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma to rapidly inhibit neuropathic pain in rats. J Pain. 2008;9:639–649. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciruela A, Dixon AK, Bramwell S, Gonzalez MI, Pinnock RD, Lee K. Identification of MEK1 as a novel target for the treatment of neuropathic pain. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2003;138:751–756. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark JB, Palmer CJ, Shaw WN. The diabetic Zucker fatty rat. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine (New York, N.Y.) 1983;173:68–75. doi: 10.3181/00379727-173-41611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corder G, Siegel A, Intondi AB, Zhang X, Zadina JE, Taylor BK. A Novel Method to Quantify Histochemical Changes Throughout the Mediolateral Axis of the Substantia Gelatinosa After Spared Nerve Injury: Characterization with TRPV1 and Substance P. The Journal of Pain. 2010;11:388–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dasu MR, Park S, Devaraj S, Jialal I. Pioglitazone inhibits Toll-like receptor expression and activity in human monocytes and db/db mice. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3457–3464. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1757. Epub 2009 Apr 3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dauch JR, Yanik BM, Hsieh W, Oh SS, Cheng HT. Neuron–astrocyte signaling network in spinal cord dorsal horn mediates painful neuropathy of type 2 diabetes. Glia. 2012;60:1301–1315. doi: 10.1002/glia.22349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies M, Brophy S, Williams R, Taylor A. The prevalence, severity, and impact of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1518–1522. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dobretsov M, Hastings SL, Romanovsky D, Stimers JR, Zhang JM. Mechanical hyperalgesia in rat models of systemic and local hyperglycemia. Brain research. 2003;960:174–183. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03828-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dobretsov M, Hastings SL, Stimers JR, Zhang JM. Mechanical hyperalgesia in rats with chronic perfusion of lumbar dorsal root ganglion with hyperglycemic solution. J Neurosci Methods. 2001;110:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00410-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donahue RR, Adkins BG, Harte SE, Studer-Rabeler KE, Taylor BK. Gabapentin reduces motivational attributes of noxious mechanical stimuli after spared nerve injury. Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2012;42:575.515. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drel VR, Lupachyk S, Shevalye H, Vareniuk I, Xu W, Zhang J, Delamere NA, Shahidullah M, Slusher B, Obrosova IG. New therapeutic and biomarker discovery for peripheral diabetic neuropathy: PARP inhibitor, nitrotyrosine, and tumor necrosis factor-{alpha} Endocrinology. 2010;151:2547–2555. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feinstein DL. Therapeutic potential of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists for neurological disease. Diabetes technology & therapeutics. 2003;5:67–73. doi: 10.1089/152091503763816481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feinstein DL, Spagnolo A, Akar C, Weinberg G, Murphy P, Gavrilyuk V, Russo CD. Receptor-independent actions of PPAR thiazolidinedione agonists: Is mitochondrial function the key? Biochemical Pharmacology. 2005;70:177–188. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feldman P, Due MR, Ripsch MS, Khanna R, White FA. The persistent release of HMGB1 contributes to tactile hyperalgesia in a rodent model of neuropathic pain. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2012;9:180. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galloway C, Chattopadhyay M. Increases in inflammatory mediators in DRG implicate in the pathogenesis of painful neuropathy in Type 2 diabetes. Cytokine. 2013;63:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao YJ, Ji RR. c-Fos and pERK, which is a better marker for neuronal activation and central sensitization after noxious stimulation and tissue injury? The open pain journal. 2009;2:11–17. doi: 10.2174/1876386300902010011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao YJ, Ji RR. Light touch induces ERK activation in superficial dorsal horn neurons after inflammation: involvement of spinal astrocytes and JNK signaling in touch-evoked central sensitization and mechanical allodynia. J Neurochem. 2010;115:505–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06946.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geldenhuys WJ, Funk MO, Barnes KF, Carroll RT. Structure-based design of a thiazolidinedione which targets the mitochondrial protein mitoNEET. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2010;20:819–823. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.12.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gregoire FM, Zhang F, Clarke HJ, Gustafson TA, Sears DD, Favelyukis S, Lenhard J, Rentzeperis D, Clemens LE, Mu Y, Lavan BE. MBX-102/JNJ39659100, a novel peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-ligand with weak transactivation activity retains antidiabetic properties in the absence of weight gain and edema. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:975–988. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0473. Epub 2009 Apr 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griggs RB, Donahue RR, Morgenweck J, Grace PM, Sutton A, Watkins LR, Taylor BK. Pioglitazone rapidly reduces neuropathic pain through astrocyte and nongenomic PPARgamma mechanisms. Pain. 2015;156:469–482. doi: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460333.79127.be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasegawa-Moriyama M, Ohnou T, Godai K, Kurimoto T, Nakama M, Kanmura Y. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist rosiglitazone attenuates postincisional pain by regulating macrophage polarization. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2012;426:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He Y, Tian X, Hu X, Porreca F, Wang ZJ. Negative reinforcement reveals non-evoked ongoing pain in mice with tissue or nerve injury. J Pain. 2012;13:598–607. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hidmark A, Fleming T, Vittas S, Mendler M, Deshpande D, Groener JB, Muller BP, Reeh PW, Sauer SK, Pham M, Muckenthaler MU, Bendszus M, Nawroth PP. A New Paradigm to Understand and Treat Diabetic Neuropathy. Experimental and clinical endocrinology & diabetes : official journal, German Society of Endocrinology [and] German Diabetes Association. 2014;122:201–207. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1367023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ibrahim SM, El-Denshary ES, Abdallah DM. Geraniol, Alone and in Combination with Pioglitazone, Ameliorates Fructose-Induced Metabolic Syndrome in Rats via the Modulation of Both Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Status. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117516. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Illien-Junger S, Lu Y, Qureshi SA, Hecht AC, Cai W, Vlassara H, Striker GE, Iatridis JC. Chronic ingestion of advanced glycation end products induces degenerative spinal changes and hypertrophy in aging pre-diabetic mice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116625. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jasmin L, Kohan L, Franssen M, Janni G, Goff JR. The cold plate as a test of nociceptive behaviors: description and application to the study of chronic neuropathic and inflammatory pain models. Pain. 1998;75:367–382. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ji RR, Baba H, Brenner GJ, Woolf CJ. Nociceptive-specific activation of ERK in spinal neurons contributes to pain hypersensitivity. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:1114–1119. doi: 10.1038/16040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiménez-Aranda A, Fernández-Vázquez G, Campos D, Tassi M, Velasco-Perez L, Tan D-X, Reiter RJ, Agil A. Melatonin induces browning of inguinal white adipose tissue in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Journal of Pineal Research. 2013;55:416–423. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kamiya H, Murakawa Y, Zhang W, Sima AA. Unmyelinated fiber sensory neuropathy differs in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2005;21:448–458. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kapadia R, Yi JH, Vemuganti R. Mechanisms of anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective actions of PPAR-gamma agonists. Front Biosci. 2008;13:1813–1826. doi: 10.2741/2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kender Z, Fleming T, Kopf S, Torzsa P, Grolmusz V, Herzig S, Schleicher E, Racz K, Reismann P, Nawroth PP. Effect of Metformin on Methylglyoxal Metabolism in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Experimental and clinical endocrinology & diabetes : official journal, German Society of Endocrinology [and] German Diabetes Association. 2014;122:316–319. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1371818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim KK, Adelstein RS, Kawamoto S. Identification of neuronal nuclei (NeuN) as Fox-3, a new member of the Fox-1 gene family of splicing factors. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31052–31061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.052969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.King T, Vera-Portocarrero L, Gutierrez T, Vanderah TW, Dussor G, Lai J, Fields HL, Porreca F. Unmasking the tonic-aversive state in neuropathic pain. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1364–1366. doi: 10.1038/nn.2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Latham JR, Pathirathna S, Jagodic MM, Choe WJ, Levin ME, Nelson MT, Lee WY, Krishnan K, Covey DF, Todorovic SM, Jevtovic-Todorovic V. Selective T-type calcium channel blockade alleviates hyperalgesia in ob/ob mice. Diabetes. 2009;58:2656–2665. doi: 10.2337/db08-1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lau D, Harte SE, Morrow TJ, Wang S, Mata M, Fink DJ. Herpes Simplex Virus Vector–Mediated Expression of Interleukin-10 Reduces Below-Level Central Neuropathic Pain After Spinal Cord Injury. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 2012;26:889–897. doi: 10.1177/1545968312445637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lecca D, Nevin DK, Mulas G, Casu MA, Diana A, Rossi D, Sacchetti G, Carta AR. Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties of a novel non-thiazolidinedione PPARgamma agonist in vitro and in MPTP-treated mice. Neuroscience. 2015;302:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee-Kubli CA, Mixcoatl-Zecuatl T, Jolivalt CG, Calcutt NA. Animal Models of Diabetes-Induced Neuropathic Pain. Current topics in behavioral neurosciences. 2014;20:140–170. doi: 10.1007/7854_2014_280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lewis JD, Ferrara A, Peng T, Hedderson M, Bilker WB, Quesenberry CP, Vaughn DJ, Nessel L, Selby J, Strom BL. Risk of Bladder Cancer Among Diabetic Patients Treated With Pioglitazone: Interim report of a longitudinal cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:916–922. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li F, Abatan OI, Kim H, Burnett D, Larkin D, Obrosova IG, Stevens MJ. Taurine reverses neurological and neurovascular deficits in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Neurobiology of disease. 2006;22:669–676. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li N, Young MM, Bailey CJ, Smith ME. NMDA and AMPA glutamate receptor subtypes in the thoracic spinal cord in lean and obese-diabetic ob/ob mice. Brain research. 1999;849:34–44. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li S, Zhai X, Rong P, McCabe MF, Wang X, Zhao J, Ben H, Wang S. Therapeutic effect of vagus nerve stimulation on depressive-like behavior, hyperglycemia and insulin receptor expression in zucker Fatty rats. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liao Y-H, Zhang G-H, Jia D, Wang P, Qian N-S, He F, Zeng X-T, He Y, Yang Y-L, Cao D-Y, Zhang Y, Wang D-S, Tao K-S, Gao C-J, Dou K-F. Spinal astrocytic activation contributes to mechanical allodynia in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Brain research. 2011;1368:324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liberman O, Peleg R, Shvartzman P. Chronic pain in type 2 diabetic patients: A cross-sectional study in primary care setting. The European journal of general practice. 2014;20:260–267. doi: 10.3109/13814788.2014.887674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma J, Yu H, Liu J, Chen Y, Wang Q, Xiang L. Metformin attenuates hyperalgesia and allodynia in rats with painful diabetic neuropathy induced by streptozotocin. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;764:599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maeda T, Kiguchi N, Kobayashi Y, Ozaki M, Kishioka S. Pioglitazone attenuates tactile allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in mice subjected to peripheral nerve injury. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008;108:341–347. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08207fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maeshiba Y, Kiyota Y, Yamashita K, Yoshimura Y, Motohashi M, Tanayama S. Disposition of the new antidiabetic agent pioglitazone in rats, dogs, and monkeys. Arzneimittel-Forschung. 1997;47:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mao-Ying QL, Kavelaars A, Krukowski K, Huo XJ, Zhou W, Price TJ, Cleeland C, Heijnen CJ. The anti-diabetic drug metformin protects against chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in a mouse model. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McTigue DM. Potential Therapeutic Targets for PPARgamma after Spinal Cord Injury. PPAR Res. 2008;2008:517162. doi: 10.1155/2008/517162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mendell JR, Sahenk Z. Painful Sensory Neuropathy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348:1243–1255. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp022282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Minoura H, Takeshita S, Kimura C, Hirosumi J, Takakura S, Kawamura I, Seki J, Manda T, Mutoh S. Mechanism by which a novel non-thiazolidinedione peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ agonist, FK614, ameliorates insulin resistance in Zucker fatty rats. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2007;9:369–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2006.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moreno S, Farioli-Vecchioli S, Cerù MP. Immunolocalization of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and retinoid x receptors in the adult rat CNS. Neuroscience. 2004;123:131–145. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morgenweck J, Abdel-aleem OS, McNamara KC, Donahue RR, Badr MZ, Taylor BK. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor [gamma] in brain inhibits inflammatory pain, dorsal horn expression of Fos, and local edema. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:337–345. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morgenweck J, Griggs RB, Donahue RR, Zadina JE, Taylor BK. PPARgamma activation blocks development and reduces established neuropathic pain in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2013;70:236–246. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morrow TJ, Harte SE. Mechanical Conflict System (MCS): A Novel Operant Method for Assessing Acute and Chronic Nociception. Winter Conference on Brain Research Abstracts. 2010;43:138. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Munoz MC, Barbera A, Dominguez J, Fernandez-Alvarez J, Gomis R, Guinovart JJ. Effects of tungstate, a new potential oral antidiabetic agent, in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Diabetes. 2001;50:131–138. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Obrosova I. Diabetic painful and insensate neuropathy: Pathogenesis and potential treatments. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6:638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Obrosova IG, Drel VR, Pacher P, Ilnytska O, Wang ZQ, Stevens MJ, Yorek MA. Oxidative-nitrosative stress and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) activation in experimental diabetic neuropathy: the relation is revisited. Diabetes. 2005;54:3435–3441. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.12.3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Obrosova IG, Xu W, Lyzogubov VV, Ilnytska O, Mashtalir N, Vareniuk I, Pavlov IA, Zhang J, Slusher B, Drel VR. PARP inhibition or gene deficiency counteracts intraepidermal nerve fiber loss and neuropathic pain in advanced diabetic neuropathy. Free radical biology & medicine. 2008;44:972–981. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Otto KJ, Wyse BD, Cabot PJ, Smith MT. Longitudinal Study of Painful Diabetic Neuropathy in the Zucker Diabetic Fatty Rat Model of Type 2 Diabetes: Impaired Basal G-Protein Activity Appears to Underpin Marked Morphine Hyposensitivity at 6 Months. Pain Medicine. 2011;12:437–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Otto M, Bak Sr, Bach FW, Jensen TS, Sindrup H., Sr Pain phenomena and possible mechanisms in patients with painful polyneuropathy. Pain. 2003;101:187–192. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Park SW, Yi JH, Miranpuri G, Satriotomo I, Bowen K, Resnick DK, Vemuganti R. Thiazolidinedione class of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists prevents neuronal damage, motor dysfunction, myelin loss, neuropathic pain, and inflammation after spinal cord injury in adult rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:1002–1012. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.113472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Patel J, Anderson RJ, Rappaport EB. Rosiglitazone monotherapy improves glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a twelve-week, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 1999;1:165–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.1999.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Piercy V, Banner SE, Bhattacharyya A, Parsons AA, Sanger GJ, Smith SA, Bingham S. Thermal, But Not Mechanical, Nociceptive Behavior is Altered in the Zucker Diabetic Fatty Rat and Is Independent of Glycemic Status. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications. 1999;13:163–169. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(99)00034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Purwata TE. High TNF-alpha plasma levels and macrophages iNOS and TNF-alpha expression as risk factors for painful diabetic neuropathy. Journal of pain research. 2011;4:169–175. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S21751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ramos KM, Jiang Y, Svensson CI, Calcutt NA. Pathogenesis of spinally mediated hyperalgesia in diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:1569–1576. doi: 10.2337/db06-1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Randall LO, Selitto JJ, Valdes J. Anti-inflammatory effects of xylopropamine. Archives internationales de pharmacodynamie et de therapie. 1957;113:233–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ren PC, Zhang Y, Zhang XD, An LJ, Lv HG, He J, Gao CJ, Sun XD. High-mobility group box 1 contributes to mechanical allodynia and spinal astrocytic activation in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Brain Res Bull. 2012;88:332–337. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Roane DS, Porter JR. Nociception and opioid-induced analgesia in lean (Fa/-) and obese (fa/fa) Zucker rats. Physiol Behav. 1986;38:215–218. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Romanovsky D, Walker JC, Dobretsov M. Pressure pain precedes development of type 2 disease in Zucker rat model of diabetes. Neuroscience Letters. 2008;445:220–223. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.08.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rong PJ, Ma SX. Electroacupuncture Zusanli (ST36) on Release of Nitric Oxide in the Gracile Nucleus and Improvement of Sensory Neuropathies in Zucker Diabetic Fatty Rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:134545. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sacks DB. A1C Versus Glucose Testing: A Comparison. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:518–523. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saito T, Hasegawa-Moriyama M, Kurimoto T, Yamada T, Inada E, Kanmura Y. Resolution of Inflammation by Resolvin D1 Is Essential for Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor-gamma-mediated Analgesia during Postincisional Pain Development in Type 2 Diabetes. Anesthesiology. 2015 doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Saitoh Y, Liu R, Ueno H, Mizuta M, Nakazato M. Oral pioglitazone administration increases food intake through ghrelin-independent pathway in Zucker fatty rat. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2007;77:351–356. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sauerbeck A, Gao J, Readnower R, Liu M, Pauly JR, Bing G, Sullivan PG. Pioglitazone attenuates mitochondrial dysfunction, cognitive impairment, cortical tissue loss, and inflammation following traumatic brain injury. Experimental Neurology. 2011;227:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schmidt RE, Dorsey DA, Beaudet LN, Parvin CA, Zhang W, Sima AA. Experimental rat models of types 1 and 2 diabetes differ in sympathetic neuroaxonal dystrophy. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2004;63:450–460. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.5.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schmidt RE, Dorsey DA, Beaudet LN, Peterson RG. Analysis of the Zucker Diabetic Fatty (ZDF) type 2 diabetic rat model suggests a neurotrophic role for insulin/IGF-I in diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:21–28. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63626-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schuelert N, Gorodetskaya N, Just S, Doods H, Corradini L. Electrophysiological characterization of spinal neurons in different models of diabetes type 1 and type 2- induced neuropathy in rats. Neuroscience. 2015;291:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schwartz S, Etropolski M, Shapiro DY, Okamoto A, Lange R, Haeussler J, Rauschkolb C. Safety and efficacy of tapentadol ER in patients with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: results of a randomized-withdrawal, placebo-controlled trial. Current medical research and opinion. 2011;27:151–162. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.537589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shevalye H, Watcho P, Stavniichuk R, Dyukova E, Lupachyk S, Obrosova IG. Metanx Alleviates Multiple Manifestations of Peripheral Neuropathy and Increases Intraepidermal Nerve Fiber Density in Zucker Diabetic Fatty Rats. Diabetes. 2012:1–8. doi: 10.2337/db11-1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Smith HS, Argoff CE. Pharmacological Treatment of Diabetic Neuropathic Pain. Drugs. 2011;71:557–589. doi: 10.2165/11588940-000000000-00000. doi:510.2165/11588940-000000000-000000000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sufka KJ. Conditioned place preference paradigm: a novel approach for analgesic drug assessment against chronic pain. Pain. 1994;58:355–366. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sugimoto K, Rashid IB, Kojima K, Shoji M, Tanabe J, Tamasawa N, Suda T, Yasujima M. Time course of pain sensation in rat models of insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and exogenous hyperinsulinaemia. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews. 2008;24:642–650. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sveen KA, Karimé B, Jørum E, Mellgren SI, Fagerland MW, Monnier VM, Dahl-Jørgensen K, Hanssen KF. Small- and Large-Fiber Neuropathy After 40 Years of Type 1 Diabetes: Associations with glycemic control and advanced protein glycation: The Oslo Study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3712–3717. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Swett JE, Woolf CJ. The somatotopic organization of primary afferent terminals in the superficial laminae of the dorsal horn of the rat spinal cord. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1985;231:66–77. doi: 10.1002/cne.902310106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Takahashi T, Yamamoto M, Amikura K, Kato K, Serizawa T, Serizawa K, Akazawa D, Aoki T, Kawai K, Ogasawara E, Hayashi J, Nakada K, Kainoh M. A novel MitoNEET ligand, TT01001, improves diabetes and ameliorates mitochondrial function in db/db mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;352:338–345. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.220673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Takahashi Y, Hasegawa-Moriyama M, Sakurai T, Inada E. The macrophage-mediated effects of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist rosiglitazone attenuate tactile allodynia in the early phase of neuropathic pain development. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:398–404. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31821b220c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Taylor BK. Resolvin D1: A New Path to Unleash the Analgesic Potential of Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor-gamma for Postoperative Pain in Patients with Diabetes. Anesthesiology. 2015 doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tomlinson DR, Gardiner NJ. Glucose neurotoxicity. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2008;9:36–45. doi: 10.1038/nrn2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Uceyler N, Rogausch JP, Toyka KV, Sommer C. Differential expression of cytokines in painful and painless neuropathies. Neurology. 2007;69:42–49. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000265062.92340.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Van Acker K, Bouhassira D, De Bacquer D, Weiss S, Matthys K, Raemen H, Mathieu C, Colin IM. Prevalence and impact on quality of life of peripheral neuropathy with or without neuropathic pain in type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients attending hospital outpatients clinics. Diabetes & metabolism. 2009;35:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vera G, Lopez-Miranda V, Herradon E, Martin MI, Abalo R. Characterization of cannabinoid-induced relief of neuropathic pain in rat models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2012;102:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vincent AM, Callaghan BC, Smith AL, Feldman EL. Diabetic neuropathy: cellular mechanisms as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:573–583. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wagner K, Yang J, Inceoglu B, Hammock BD. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition is antinociceptive in a mouse model of diabetic neuropathy. J Pain. 2014;15:907–914. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang G, Liu L, Zhang Y, Han D, Lu J, Xu J, Xie X, Wu Y, Zhang D, Ke R, Li S, Zhu Y, Feng W, Li M. Activation of PPARγ attenuates LPS-induced acute lung injury by inhibition of HMGB1-RAGE levels. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2014;726:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Watanabe Y, Nakayama K, Taniuchi N, Horai Y, Kuriyama C, Ueta K, Arakawa K, Senbonmatsu T, Shiotani M. Beneficial effects of canagliflozin in combination with pioglitazone on insulin sensitivity in rodent models of obese type 2 diabetes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wienemann T, Chantelau EA, Richter A. Pressure pain perception at the injured foot: the impact of diabetic neuropathy. Journal of musculoskeletal & neuronal interactions. 2012;12:254–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2011;152:S2–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Xu W, Bi Y, Sun Z, Li J, Guo L, Yang T, Wu G, Shi L, Feng Z, Qiu L, Li Q, Guo X, Luo Z, Lu J, Shan Z, Yang W, Ji Q, Yan L, Li H, Yu X, Li S, Zhou Z, Lv X, Liang Z, Lin S, Zeng L, Yan J, Ji L, Weng J. Comparison of the effects on glycaemic control and β-cell function in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes patients of treatment with exenatide, insulin or pioglitazone: a multicentre randomized parallel-group trial (the CONFIDENCE study) Journal of Internal Medicine. 2015;277:137–150. doi: 10.1111/joim.12293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Xu X, Chen H, Ling BY, Xu L, Cao H, Zhang YQ. Extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase activation in spinal cord contributes to pain hypersensitivity in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Neurosci Bull. 2014;30:53–66. doi: 10.1007/s12264-013-1387-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]