Abstract

The hydrogen uptake (Hup) system of Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens recycles the H2 released by nitrogenase in soybean nodule symbiosis, and is responsible for H2-dependent chemolithoautotrophic growth. The strain USDA110 has two hup gene clusters located outside (locus I) and inside (locus II) a symbiosis island. Bacterial growth under H2-dependent chemolithoautotrophic conditions was markedly weaker and H2 production by soybean nodules was markedly stronger for the mutant of hup locus I (ΔhupS1L1) than for the mutant of hup locus II (ΔhupS2L2). These results indicate that locus I is primarily responsible for Hup activity.

Keywords: Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens, chemolithoautotrophic growth, hydrogenase, symbiosis

Soybean bradyrhizobia have two lifestyles: as symbiotic bacteroids that fix atmospheric nitrogen in host plants or as free-living soil bacteria. As a symbiont, B. diazoefficiens synthesizes a hydrogen uptake (Hup) system that recycles the H2 formed as a byproduct of nitrogenase activity (4). This symbiotic hydrogen oxidation increases nitrogen fixation efficiency, thereby enhancing the productivity of the legume host (3, 6). As free-living cells, Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens Hup+ strains have the ability to grow chemolithoautotrophically by using H2 as an electron donor (7).

Two sets of hup genes have been identified in B. diazoefficiens: a large cluster outside the symbiosis island (hup locus I, genome position 7,620,025–7,645,755) and a small cluster inside the symbiosis island (hup locus II, genome position 1,888,916–1,902,575) (6, 11). A transcriptome analysis previously showed that several hup genes located outside the symbiosis island were up-regulated during H2-dependent chemolithoautotrophic growth, whereas several hup genes located inside the symbiosis island were up-regulated in symbiotic bacteroids (1, 6). These findings imply that hup locus I plays an important role in chemolithoautotrophic growth, while symbiotic hup locus II may contribute to Hup activity in the nodules. In the present study, we constructed hupSL deletion mutants in order to clarify the contribution of each hup gene cluster during the chemolithoautotrophic growth and nodulation of B. diazoefficiens USDA110.

Materials and Methods

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The HM salt medium for the preculture and Hup medium for chemolithoautotrophic growth were described previously (14). Antibiotics were added to the media for B. diazoefficiens USDA110 and Escherichia coli strains as described previously (13).

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in the present study.

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens | ||

| USDA110 | Soybean bradyrhizobia, wild type | 11 |

| ΔhupS1L1 | USDA110 hupS1L1::aadA; Smr Spr | This study |

| ΔhupS2L2 | USDA110 hupS2L2::tet; Tcr | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | cloning strain | Toyobo Inc.a |

| Plasmids | ||

| p34S-Tc | Plasmid carrying a 2.1-kb Tc cassette; Tcr | 2 |

| pHP45Ω | Plasmid carrying a 2.1-kb Ω cassette; Spr Smr Apr | 15 |

| pK18mob-hupI | pK18mob carrying a 5.9-kb hupFDCL1S1VU HindIII fragment of brp15657; Kmr | This study |

| pK18mob-hupIad | pK18mob-hupI with an ApaI/EcoRI adaptor; Kmr | This study |

| pK18mob-hupIomega | pK18mob carrying hupS1L1::aadA; Smr Spr Kmr | This study |

| pK18mob-hupII | pK18mob carrying a 7.6-kb hupS2L2CDFHK XhoI fragment of brp07428; Tcr | This study |

| pK18mob-hupIIad | pK18mob-hupII with an EcoO109I/BamHI adaptor; Kmr | This study |

| pK18mob-hupIITc | pK18mob carrying hupS2L2::tet; Tcr Kmr | This study |

| pK18mob | cloning vector; pMB1ori oriT; Kmr | 16 |

| pRK2013 | ColE1 replicon carrying RK2 transfer genes; Kmr | 5 |

| brp15657 | pUC18 carrying hupUVS1L1CDFG | 11 |

| brp07423 | pUC18 carrying hupKHFDCL2S2 | 11 |

Apr, ampicillin-resistant; Tcr, tetracycline-resistant; Kmr, kanamycin-resistant; Smr, streptomycin-resistant; Spr, spectinomycin-resistant.

Osaka, Japan.

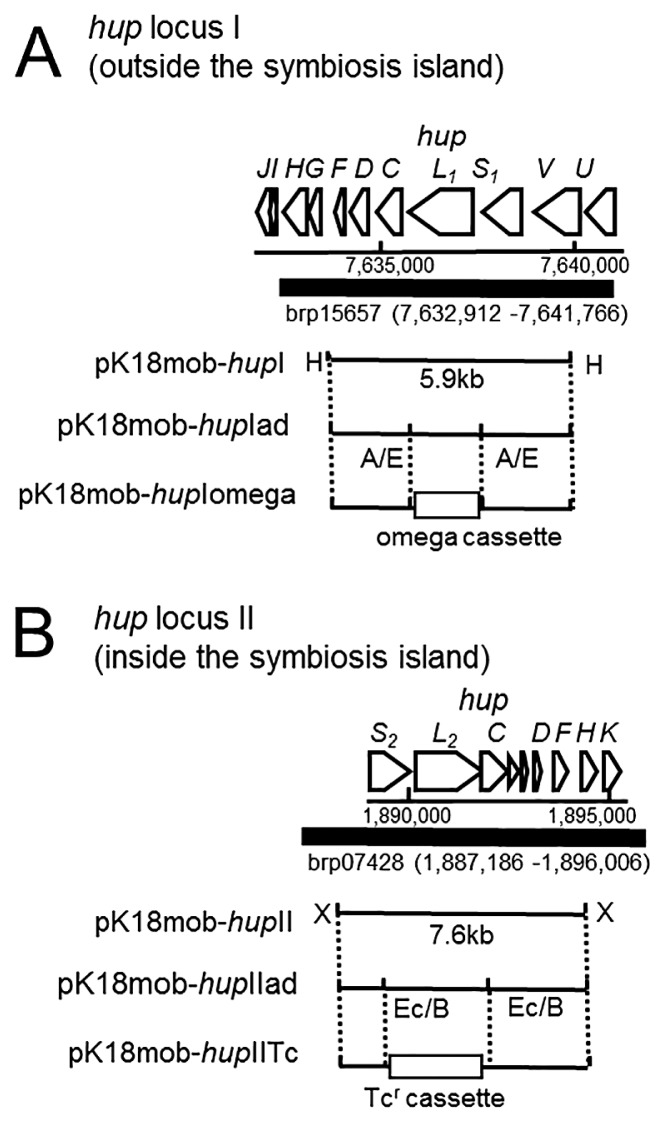

We generated hupS1L1 and hupS2L2 deletion mutants as follows. A DNA fragment containing hupFDCL1S1V was isolated from brp15657, a plasmid from the pUC18 clone library of B. diazoefficiens USDA110 sequences (11), and inserted into the HindIII site of pK18mob. The resultant plasmid, pK18mob-hupI, was digested with ApaI and ligated with the ApaI/EcoRI adaptor, yielding pK18mob-hupIad. The omega cassette isolated from pHP45Ω was inserted at the EcoRI site of pK18mob-hupIad, yielding pK18mob-hupIomega. Triparental mating using pRK2013 was performed as described previously (13). A similar strategy was used to construct the hupS2L2 deletion mutant. Briefly, hupKHFDCL2S2 was isolated from brp07423, and inserted into pK18mob, yielding pK18mob-hupII. pK18mob-hupII was ligated with the EcoO109I/BamHI adaptor, resulting in pK18mob-hupIIad. The Tcr cassette was isolated from p34S-Tc and inserted into the BamHI site of pK18mob-hupIIad, yielding pK18mob-hupIITc. The double crossover events of these deletion mutations were verified by a Southern blot analysis.

The inoculants were prepared as described previously (14). Aliquots (10 μL) of the cells (OD660 at 0.1) were streaked on Hup medium, and the agar plates were statically incubated at 25°C for 14 d in an atmosphere containing 1% O2, 5% CO2, 10% H2, and 84% N2.

Soybean seedlings (Glycine max cv. Enrei) grown in a plant box in a growth chamber were inoculated with B. diazoefficiens as described previously (8, 9). The nodulated roots were transferred into a 300-mL bottle 30 d later, and a 0.5-mL gas sample from the head space of the bottle was injected into a GC-2014 gas chromatograph (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) as described previously (13). The flow rate of the carrier gas (N2) was 30 mL min−1.

Results

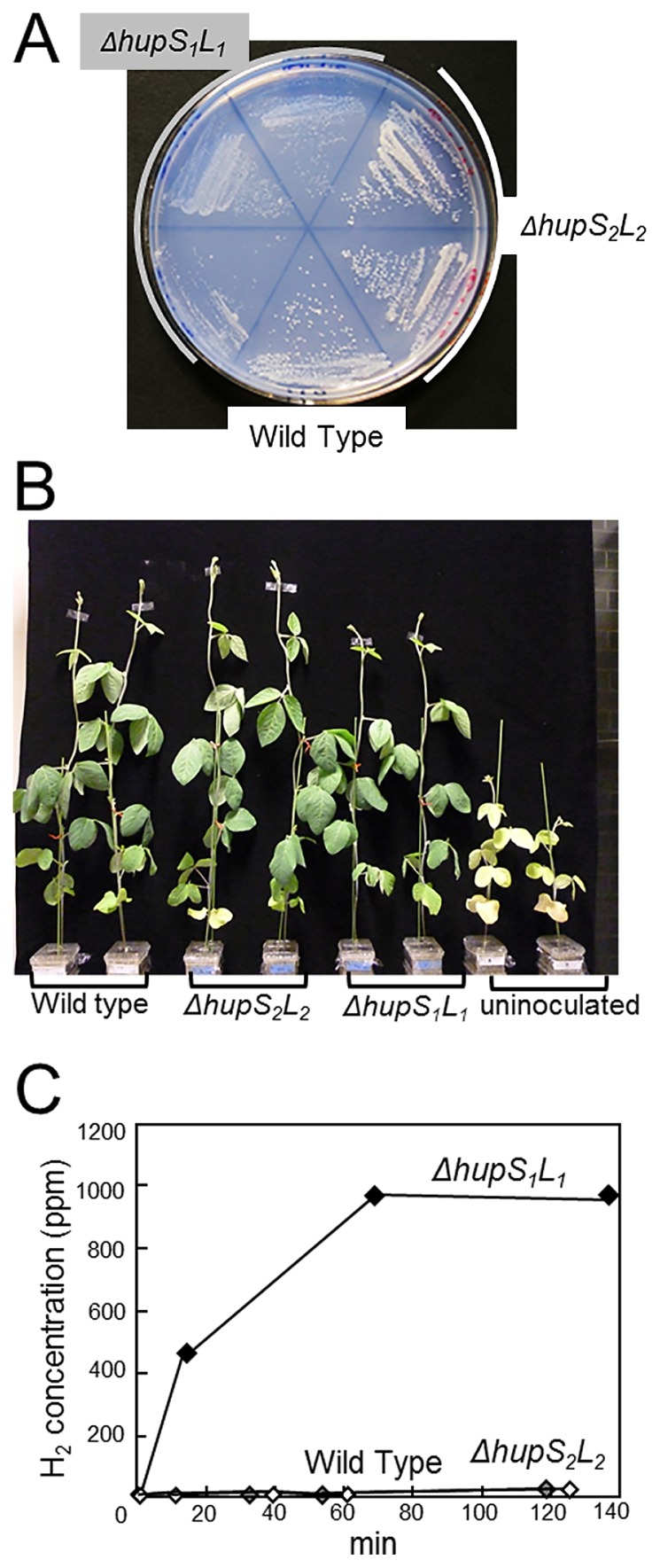

Wild-type USDA110 and the ΔhupS2L2 mutant grew on Hup agar medium under chemolithoautotrophic growth conditions (Fig. 2A). However, the ΔhupS1L1 mutant showed markedly weaker growth than that of the wild type on this medium (Fig. 2A). The height of plants inoculated with ΔhupS1L1 appeared to be lower than those inoculated with the wild type and ΔhupS2L2 mutant (Fig. 2B); however, no significant differences were observed in plant dry weights or fresh nodule weights (Table 2). H2 was not produced from the nodulating roots of the wild type or ΔhupS2L2 mutant (Fig. 2C), indicating that Hup activity compensated for the production of H2 via nitrogenase. In contrast, H2 was produced by the ΔhupS1L1 nodules (6.4 μmol h−1 g fresh nodule weight−1) (Fig. 2C), indicating that Hup activity was lower than the production of H2 via nitrogenase. These results suggest that hup genes outside the symbiosis island are the primary cluster involved in chemolithoautotrophic growth and Hup activity in the nodules.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of chemolithoautotrophic growth (A) and symbiotic phenotypes (BC) between hup mutants and the wild-type strain of B. diazoefficiens USDA110. (A) Growth phenotype on Hup agar medium under an atmosphere of 84% N2, 10% H2, 5% CO2, and 1% O2 at 25°C. (B) Plant growth 30 d after inoculation. (C) Concentration of H2 produced by the root nodules. White squares, wild type; black squares, ΔhupS1L1 mutant; grey squares, ΔhupS2L2 mutant.

Table 2.

Plant dry weights and fresh nodule weights of inoculated wild-type USDA110 and mutants.

| Strains | Plant dry weight (g) | Fresh nodule weight (g) |

|---|---|---|

| USDA110 | 6.9 ± 0.9a | 1.36 ± 0.20a |

| ΔhupS1L1 | 6.8 ± 1.1a | 1.38 ± 0.20a |

| ΔhupS2L2 | 6.9 ± 0.6a | 1.29 ± 0.13a |

Plants were harvested 30 d after inoculation. Values are presented as an average and standard deviation (n=5). Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for statistical analyses (p<0.05).

Discussion

In the present study, the mutation of hupS2L2 did not change nodule H2 production from that by wild-type USDA110 (Fig. 2C), even though some genes on hup locus II were up-regulated in symbiotic bacteroids (1, 6). Hup locus I contains a complete set of the hup-hyp-hox cluster, and is missing from hup locus II (11). Thus, hupS2L2 in locus II may not be fully induced without the hup gene assemblage, resulting in no or weak Hup activity by the hupS2L2 genes. On the other hand, the hup gene cluster outside the symbiosis island, which we identified as the primary hup gene cluster contributing to Hup activity in free-living and symbiotic cells, is located on a typical genomic island (trnM element) of B. diazoefficiens USDA110. The trnM element is likely acquired in the USDA110 lineage after the divergence of strains USDA110 and USDA6T because B. japonicum USDA6T completely lacks this element (10, 11, 12).

Hup genes were also found in the symbiosis island of the USDA6T genome even though USDA6T was previously reported to exhibit no Hup activity (10, 11, 12). The hup genes in USDA6T on the symbiosis island had 99–100% amino acid sequence identity to the corresponding genes in hup locus II of USDA110. In contrast, USDA6T hup genes had only 43–83% amino acid sequence identity to genes in hup locus I of USDA110, which is similar to the homology (45–83%) between hup genes in loci I and II of USDA110. These results suggest that hup genes on locus II of USDA110 and hup genes in USDA6T do not contribute to the Hup activities of these strains and appear to be derived from the acquisition of symbiosis islands. Therefore, our results imply the horizontal gene transfer of the primary hup cluster via the genomic island to the lineage of B. diazoefficiens rather than symbiosis island transfer.

Fig. 1.

Gene maps of hup gene clusters in B. diazoefficiens. (A) Gene map of hup locus I showing the genome position of hup locus I and brp15657. pK18mob-hupI carries a 5.9-kb DNA fragment containing hupFDCL1S1V genes. pK18mob-hupIad was ligated with an ApaI/EcoRI adaptor. pK18mob-hupIomega had an omega cassette, which was inserted at the EcoRI site of pK18mob-hupIad. (B) Gene map of hup locus II showing the genome position of hup locus II and brp07428. The strategy used to construct the hupS2L2 deletion mutant is shown as the hupS1L1 deletion mutant. H, HindIII; A, ApaI; E, EcoRI; X, XhoI; Ec, EcoO109I; B, BamHI, Tcr, tetracycline-resistant.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan (BRAIN) and by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) 26252065 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

References

- 1.Chang WS, Franck WL, Cytryn E, Jeong S, Joshi T, Emerich DW, Sadowsky MJ, Xu D, Stacey G. An oligonucleotide microarray resource for transcriptional profiling of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007;20:1298–1307. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-10-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dennis JJ, Zylstra GJ. Plasposons: modular self-cloning minitransposon derivatives for rapid genetic analysis of gram-negative bacterial genomes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2710–2715. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2710-2715.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drevon J, Kalia VC, Heckmann M, Salsac I. Influence of the Bradyrhizobium hydrogenase on the growth of Glycine and Vigna species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:610–612. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.3.610-612.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans HJ, Harker AR, Papen H, Russell SA, Hanus FJ, Zuber M. Physiology, biochemistry, and genetics of the uptake hydrogenase in rhizobia. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:335–361. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.002003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Figruski DH, Helinski DR. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1648–1652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franck WL, Chang WS, Qiu J, Sugawara M, Sadowsky MJ, Smith SA, Stacey G. Whole-genome transcriptional profiling of Bradyrhizobium japonicum during chemoautotrophic growth. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:6697–6705. doi: 10.1128/JB.00543-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanus FJ, Maier RJ, Evans HJ. Autotrophic growth of H2-uptake-positive strains of Rhizobium japonicum in an atmosphere supplied with hydrogen gas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1788–1792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inaba S, Ikenishi F, Itakura M, Kikuchi M, Eda S, Chiba N, Katayama C, Suwa Y, Mitsui H, Minamisawa K. N2O emission from degraded soybean nodules depends on denitrification by Bradyrhizobium japonicum and other microbes in the rhizosphere. Microbes Environ. 2012;27:470–476. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME12100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Itakura M, Tabata K, Eda S, Mitsui H, Murakami K, Yasuda J, Minamisawa K. Generation of Bradyrhizobium japonicum mutants with Increased N2O reductase activity by selection after inoculation of a mutated dnaQ gene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:7258–7264. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01850-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Itakura M, Saeki K, Omori H, et al. Genomic comparison of Bradyrhizobium japonicum strains with different symbiotic nitrogen-fixing capabilities and other Bradyrhizobiaceae members. ISME J. 2008;3:326–339. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaneko T, Nakamura Y, Sato S, et al. Complete genomic sequence of nitrogen-fixing symbiotic bacterium Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110. DNA Res. 2002;9:189–197. doi: 10.1093/dnares/9.6.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaneko T, Maita H, Hirakawa H, Uchiike N, Minamisawa K, Watanabe A, Sato S. Complete genome sequence of the soybean symbiont Bradyrhizobium japonicum strain USDA6T. Gene. 2011;2:763–787. doi: 10.3390/genes2040763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masuda S, Eda S, Ikeda S, Mitsui H, Minamisawa K. Thiosulfate-dependent chemolithoautotrophic growth in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:2402–2409. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02783-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masuda S, Eda S, Sugawara C, Mitsui H, Minamisawa K. The cbbL gene is required for thiosulfate-dependent autotrophic growth of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Microbes Environ. 2010;25:220–223. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.me10124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prentki P, Krisch HM. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selective DNA fragment. Gene. 1984;29:303–313. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schäfer A, Tauch A, Jäger W, Kalinowski J, Thierbach G, Pühler A. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene. 1994;145:69–73. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]