Abstract

Study Objectives:

This study aimed to (1) examine the relationship between subjective and actigraphy-defined sleep, and next-day fatigue in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS); and (2) investigate the potential mediating role of negative mood on this relationship. We also sought to examine the effect of presleep arousal on perceptions of sleep.

Methods:

Twenty-seven adults meeting the Oxford criteria for CFS and self-identifying as experiencing sleep difficulties were recruited to take part in a prospective daily diary study, enabling symptom capture in real time over a 6-day period. A paper diary was used to record nightly subjective sleep and presleep arousal. Mood and fatigue symptoms were rated four times each day. Actigraphy was employed to provide objective estimations of sleep duration and continuity.

Results:

Multilevel modelling revealed that subjective sleep variables, namely sleep quality, efficiency, and perceiving sleep to be unrefreshing, predicted following-day fatigue levels, with poorer subjective sleep related to increased fatigue. Lower subjective sleep efficiency and perceiving sleep as unrefreshing predicted reduced variance in fatigue across the following day. Negative mood on waking partially mediated these relationships. Increased presleep cognitive and somatic arousal predicted self-reported poor sleep. Actigraphy-defined sleep, however, was not found to predict following-day fatigue.

Conclusions:

For the first time we show that nightly subjective sleep predicts next-day fatigue in CFS and identify important factors driving this relationship. Our data suggest that sleep specific interventions, targeting presleep arousal, perceptions of sleep and negative mood on waking, may improve fatigue in CFS.

Citation:

Russell C, Wearden AJ, Fairclough G, Emsley RA, Kyle SD. Subjective but not actigraphy-defined sleep predicts next-day fatigue in chronic fatigue syndrome: a prospective daily diary study. SLEEP 2016;39(4):937–944.

Keywords: actigraphy, chronic fatigue syndrome, daily diary study, insomnia, sleep

Significance.

This is the first study to use a prospective, daily diary approach to repeatedly examine the relationship between nightly subjective and objective sleep parameters and next-day fatigue in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS). We find that subjective sleep variables, including sleep quality, feeling refreshed on awakening and sleep efficiency, predict greater following-day fatigue, as well as reduced variance in fatigue, and that negative mood on waking partially mediates these relationships. In contrast, objective estimations of sleep did not predict next-day fatigue. Levels of presleep arousal also predicted poorer subjective sleep. Our findings could have important clinical implications, suggesting that the application of sleep-focused therapies in CFS patients may confer therapeutic value.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is a condition characterized by severe and persistent fatigue of more than 6 months duration, which has a substantial effect on daily activities.1 Difficulties with sleep are commonly reported, with up to 95% of patients experiencing unrefreshing sleep.2,3 Difficulties with initiating and maintaining sleep, and poor sleep quality are also highly prevalent in this group.4 Despite high levels of reported sleep difficulties in CFS, two recent reviews have concluded that polysomnographically measured sleep is not reliably impaired relative to healthy controls,5,6 suggesting a discrepancy between perceived sleep and objectively defined sleep. Research in the field of insomnia has consistently demonstrated a similar discrepancy, with patients overestimating wakefulness during the night and underestimating total sleep time (TST), compared with polysomnographically measured sleep.7 Presleep arousal has been found to negatively affect perceived sleep in insomnia populations, contributing to this inconsistency. In CFS, it is not known if similar psychological factors may contribute to perceptions of sleep, with potential implications for daytime function.

From a patient perspective poor sleep can be distressing and is difficult to manage.8 Patients report that poor sleep exacerbates symptoms and negatively affects daytime functioning.8 In line with this, the cognitive behavioral conceptualization of CFS suggests that disturbed sleep, in addition to a number of other factors, may be involved in the maintenance of both physical and psychological symptoms associated with CFS.9 Despite the perceived effect of poor sleep on daytime symptoms in CFS, very few studies have examined this relationship empirically. A recent study provided initial evidence by investigating associations between subjective sleep, measured using sleep diaries, and fatigue.10 Increased duration of reported wake time after sleep onset (WASO) significantly predicted increased fatigue severity. However, fatigue was measured at a single timepoint only, thus failing to capture the fluctuating nature of fatigue in CFS. Moreover, because this study only included self-reported sleep, it remains unclear whether a similar relationship exists between objectively measured sleep (e.g., using polysomnography or actigraphy) and fatigue. Due to these limitations the relationship between sleep and fatigue in CFS requires high-resolution examination.

In fibromyalgia, which has considerable overlap with CFS,11 studies using prospective designs and daily self-report measures have examined relationships between sleep and symptoms, such as pain and fatigue. This has allowed researchers to demonstrate the complexity of these relationships. For example, one study found that a significant relationship between pain and next-day fatigue was fully mediated by subjective sleep quality, as measured by sleep diaries.12 To date, however, no study has utilized a similar design to evaluate the relationship between sleep and fatigue in CFS and it remains unknown whether sleep parameters predict next-day fatigue.

Therefore, building on previous research and using a prospective daily diary approach, the current study sought to examine the relationship between subjectively and objectively measured sleep and next-day fatigue in patients with CFS. We included self-reports of sleep quality and efficiency using a sleep diary alongside estimations of sleep derived from actigraphy, to determine which parameters better predict following-day fatigue. In order to provide a thorough assessment of fatigue, multiple daily assessments were included, which allowed comparisons both within and between participants enabling a close examination of the relationship between sleep and next-day fatigue.13 The effect of presleep cognitive and somatic arousal as potential predictors of subjective sleep quality and efficiency was also assessed, in line with key observations in the insomnia literature.14 As distress is known to exacerbate the experience of symptoms in CFS,9 negative mood on waking was evaluated as a potential mediator of the relationship between sleep and next-day fatigue.

METHODS

Procedure

All participants were recruited from a specialist multidisciplinary CFS service in the United Kingdom. Ethical approval was gained from the local National Health Service Regional Ethics Committee. Patients were eligible to take part if they had a diagnosis of CFS made by a medical professional, and if they self-identified as experiencing difficulties with sleep, including difficulties with initiating and maintaining sleep, and unrefreshing sleep. Patients were excluded if they had a known current diagnosis of another sleep disorder; screened “positive” for another sleep disorder on screening interview; or if they were currently taking hypnotic medications. Eligible patients were identified by members of the clinical team and study information, containing the contact details of the researcher, was given to potential participants, either by mail or during clinical contact. A total of 280 information sheets were administered, the majority of which were sent by mail to patients on a waiting list for psychological therapy within the service.

Those who were interested in participating were asked to contact the researcher directly. Following initial contact, a meeting was arranged to discuss the study procedures, complete screening measures, and to gain informed consent. On the day of this meeting, participants were asked to begin their 6-day participation in the study, during which period the researcher was available for contact by telephone and email.

Screening Measures

Prior to participation demographic information was collected and participants were screened using a checklist to ensure that they met the Oxford Criteria for CFS.15 Information on current medications was also collected to ensure participants met inclusion criteria.

The Brief Sleep Interview16 was used to screen participants for possible sleep disorders other than insomnia prior to participation. This consists of five lead questions assessing the possible presence of narcolepsy, sleep breathing disorder, periodic limb movement disorder/restless legs syndrome, circadian rhythm disorders, and parasomnias. Additional supplementary questions are asked if any of these sleep disorders are suspected following a positive response to the lead question. If there was any uncertainty about including potential participants, decisions were made by consensus within the research team.

In addition to the aforementioned screening measures, a number of additional measures were also included in order to fully describe the current sample in terms of sleep variables, anxiety, depression, and fatigue:

The Sleep Condition Indicator17 was administered to measure ongoing sleep difficulties. It comprises eight questions reflecting sleep latency and WASO, sleep quality, duration of sleep difficulties, concern about sleep and daytime dysfunction attributed to poor sleep. Participants are asked to rate each of these domains on a typical night in the past month using a five-point scale with lower scores indicating greater difficul-ties in each domain. The SCI produces a score of 0 to 32, with scores ≤ 16 indicating probable insomnia disorder.17

We measured attitudes and beliefs about sleep using the Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Scale: Brief Version (DBAS1618), a validated questionnaire composing of 16 statements. These items measure four domains: consequences of insomnia, worry about sleep, sleep expectations, and medication. Items are rated on a 10-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree). Total scores are averaged to produce a mean item score, with a cutoff of 3.8 indicating clinical levels of dysfunctional beliefs about sleep.19

Levels of symptoms of depression and anxiety were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS20) which contains 14 items, assessing two subscales of anxiety and depression. Items are rated on a four-point scale from 0–3 (not present–substantial), and a total score on each subscale is calculated. A score of 11 or more indicates clinically significant difficulties. The HADS is commonly used in CFS studies.

To measure fatigue the Chalder Fatigue Scale,21 a widely used 11-item measure of mental and physical fatigue severity, was administered. Bimodal scoring was used with a score of 1 given for items rated “more than usual” or “much more than usual.” Items rated as “no more than usual” or “less than usual” were given a score of 0. Total scores could range from 0 to 11, with scores of 4 or more indicating clinical “caseness.”

Daily Diary Design and Measures

Actigraphy

To provide objective estimates of sleep, participants were instructed to wear a MotionWatch 8 actigraph watch (CamNtech Ltd.; Cambridge, UK), a lightweight and unobtrusive device similar to a wristwatch. The device includes a digital accelerometer which enables, based on movement, the differentiation of probable sleep and wake states for each 60-sec period of recording. Participants began wearing the device at 18:00 on the day of their meeting with the researcher, and wore this continuously over the following 6 days. Participants were also asked to press the event marker on the device when they got into bed at night, and when they got out of bed the following morning. The following sleep variables, reflecting core dimensions of the sleep period, were extracted using CamNtech MotionWatch 8 software: TST, sleep efficiency (SE, proportion of time in bed spent asleep) and sleep fragmentation index (reflecting time spent mobile during the sleep period, with higher scores indicating sleep fragmentation and discontinuity). Because sleep onset latency (SOL) and WASO contribute to and are therefore highly correlated with SE, we chose to investigate SE as the summary variable to limit excessive and redundant testing. Actigraphy has been shown to have good agreement with polysomnography-defined sleep parameters.22

Daily Diaries

Participants were asked to record their subjective experiences of sleep by completing the wake time version of the Consensus Sleep Diary (CSD23) each morning on waking. The CSD asks questions about bedtime, latency to fall asleep, duration of WASO, and rising time. From this self-reported data, perceived TST and SE can be calculated. Perceived quality of sleep during the previous night was rated on a five point scale from “very poor” to “very good.” An additional item taken from the extended version of the CSD was included, also rated on a five-point scale, which measured the extent to which participants felt “refreshed” or “rested” on waking. Participants were asked to record daytime napping by indicating the times and duration of any naps on a specific page in their daily diary.

Participants completed two additional visual analog scale (VAS) items measuring presleep cognitive arousal (“As you were trying to go to sleep last night, did thoughts keep running through your mind?”) and somatic arousal (“As you were trying to go to sleep last night, did you experience a jittery, nervous feeling in your body?”). These items were adapted from a previous daily diary study examining sleep in chronic pain,24 and are similar to items on the Pre Sleep Arousal Scale (PSAS25).

In order to measure symptoms, participants were asked to complete the Daytime Insomnia Symptom Scale (DISS26) at four time-points during each day: on waking, 12:00, 18:00, and at bedtime. The DISS is a validated measure designed for daily diary studies to characterise daytime insomnia symptom levels in real time. It consists of 20 items and has four subscales. For the current analyses the fatigue subscale was derived for each time point by summing scores on items measuring the extent to which participants felt “sleepy,” “fatigued” and “exhausted,” providing the primary outcome measure. A negative mood score was derived by summing scores on items measuring feeling “sad,” “tense,” “anxious,” “stressed” and “irritable,” completed each morning on waking. Each item is rated on a VAS scale from 0 (very little) to 100 (very much).

Participants were asked to record the time that they completed the sleep diaries and each of the symptom ratings. Any data points completed more than 1 h outside of the requested time point were excluded from analysis.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed in Stata version 13 (Stata Corporation, 2013, Texas USA). First, the main outcome variables, mean fatigue across each day, and variability (standard deviation, SD) in fatigue across each day were calculated for each participant. These were included in further analyses if participants had completed at least three of the four daily symptom ratings. As fatigue mean scores and variability across the day were used as outcomes, the daily diary design had a two-level hierarchical structure, with days nested within participant. Multilevel modeling was used to account for the clustering in outcomes within participants, and all analyses were performed using maximum likelihood estimation, which accounts for missing data under a missing-at-random assumption, conditional on the variables in the model. This has the advantage that all the available data are used in the analysis.

In the first models, subjective SE, TST, quality, and feeling refreshed, were entered as predictors with fatigue mean levels and variability as outcomes, using separate models for each outcome. To account for possible confounding, illness duration at baseline was included as an additional covariate in each of the models. Separate models were then used to examine actigraphy-defined sleep variables (TST, SE, and sleep fragmentation index) as predictors of next-day fatigue. Models examining whether presleep cognitive and somatic arousal predicted sleep variables associated with fatigue were also examined.

To test the effect of negative mood on waking as a potential mediator of the relationship between subjective sleep and fatigue, we used the difference in coefficients approach, as outlined by Bolger and Laurenceau.27 This involved first examining whether subjective sleep variables predicted negative mood on waking. Following this, the direct effect of subjective sleep variables on next-day fatigue, when negative mood on waking was added as a variable, is compared to the total effect when negative mood is not in the model. The difference between these two effects is an estimate of the indirect effect.

RESULTS

Participants

Forty-two individuals contacted the researcher with an interest in participating. Seven were not eligible to take part due to suspected additional sleep difficulties including sleep phase shift disorder (2), restless legs syndrome (2), sleep apnoea (2) and night terrors (1). Four were excluded due to taking hypnotic medications, and one because of uncertainty around their CFS diagnosis. Three individuals were too unwell or withdrew prior to participating.

Twenty-seven eligible participants completed the 6-day study period. Their mean age was 49.7 y (SD = 12.5) and 24 (89%) were female. Eighty-nine percent of the sample defined themselves as White British, two as Black British, and one as being from a mixed White and Black Caribbean ethnic background. Twenty-six percent and 22% were in employment full time and part time respectively, 37% were unable to work due to ill health, and the remaining 15% were retired. The mean illness duration of the sample was 141 mo (SD = 144 mo).

In terms of validated measures, the mean score on the Chalder Fatigue Scale was 8.8 (SD = 3.6). For the HADS, mean anxiety score was 9.8 (SD = 5.3) and mean depression score was 8.4 (SD = 4.3). The mean score on the SCI was 8.6 (SD = 4.0) and 6.2 (SD = 1.3) for DBAS.

In terms of condition management, 37% of the sample were currently undertaking some form of self-directed activity management, and a further 19% had received input from a health care professional regarding managing activity. Fifteen percent had received graded exercise therapy and 11% had previously received cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). In terms of medication, 15% were taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and 8% were taking tricyclic medications. No participant had undergone sleep focused therapy, but three participants (11%) had previously received sleep hygiene advice from a health care professional.

Descriptive Sleep Data

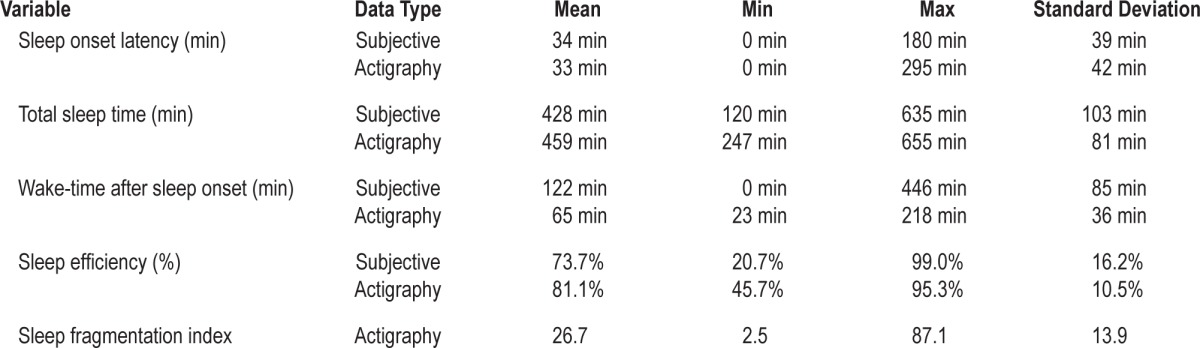

All 27 participants completed the 6-day study period and the completion rate for daily diary items was 95.7%. Descriptive information on nightly subjective ratings of sleep, derived from the sleep diary, and nightly estimations of sleep from actigraphy are shown in Table 1. Fourteen participants (51.9%) reported napping at least once during the study period, with napping reported on a small minority of study days (14.8% of total study days). The majority of those who napped (n = 8; 29.6% of total sample) reported napping on one study day only. Only six participants (22.3% of total sample) reported napping on 2 or more days. The mean duration of napping was 91.3 min (SD = 65.2).

Table 1.

Descriptive sleep data across study nights.

Preliminary Analysis

Prior to beginning the main analyses, illness duration was examined as a predictor of the main outcome variables, to determine whether illness duration might confound the relationship between sleep and fatigue. For fatigue mean outcomes, illness duration was not a significant predictor (coefficient = 0.013, P = 0.515). For variance in fatigue, illness duration was found to be a significant predictor (coefficient = −0.016, P = 0.027), with longer illness duration associated with reduced variance in fatigue across the day. Consequently, illness duration was included as a covariate in all subsequent analyses.

Predicting Daily Mean Fatigue and Variability

Subjective Sleep Variables as Predictors

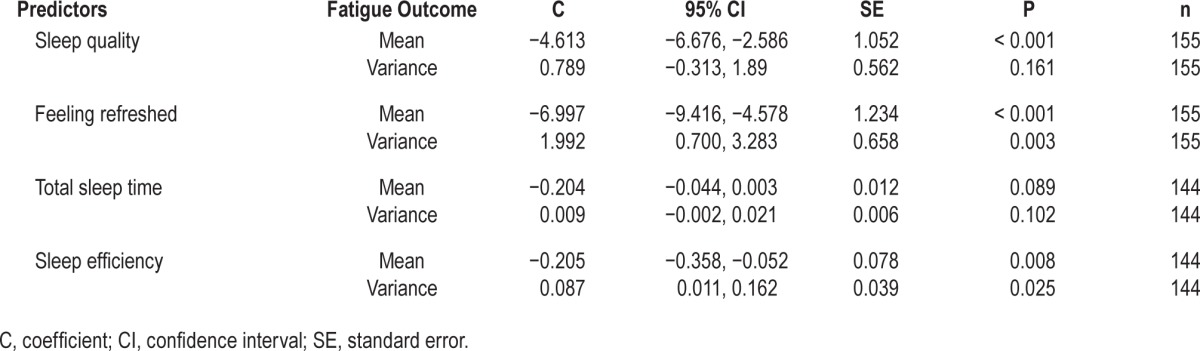

Table 2 shows each of the subjective sleep predictors, coefficients of the predictors (C), confidence intervals (CI), standard error (SE), number of observations (n), and the significance level (P) for both mean fatigue and fatigue variance outcomes.

Table 2.

Subjective sleep variables as predictors of next day fatigue mean and variance.

Poorer subjective sleep quality, lower sleep efficiency, and feeling less refreshed on waking significantly predicted higher following-day mean fatigue. Feeling less refreshed and reporting lower sleep efficiency were both associated with reduced variance in next-day fatigue.

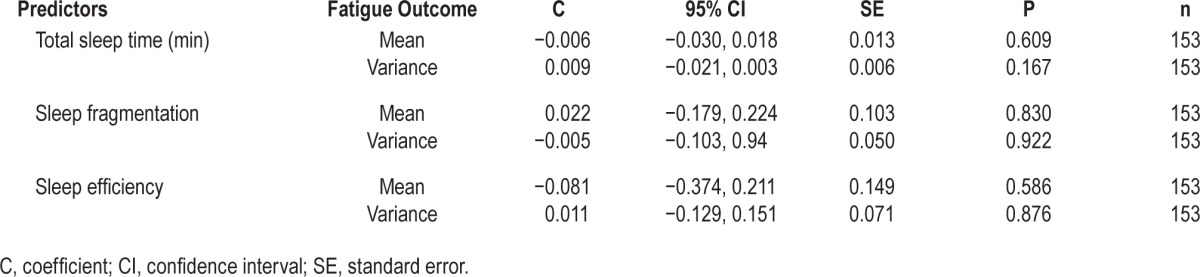

Actigraphy-Defined Sleep Variables as Predictors

Table 3 shows that mean fatigue scores and variance in fatigue scores were not predicted by actigraphy-defined sleep variables.

Table 3.

Actigraphy-defined sleep variables as predictors of next day fatigue mean and variance.

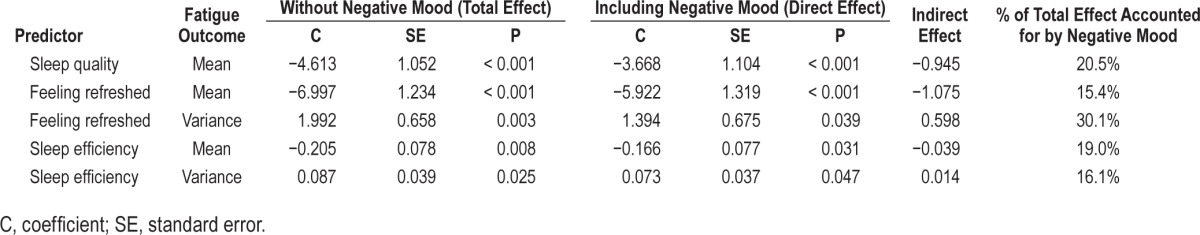

Negative Mood as a Mediator of the Relationship between Subjective Sleep and Fatigue

To examine the role of negative mood as a potential mediator of the association between subjective sleep variables and fatigue, subjective sleep variables were first examined as predictors of negative mood on waking. Negative mood on waking was predicted by lower sleep quality (coefficient = −5.418, P < 0.001), feeling less refreshed by sleep (coefficient = −6.701, P < 0.001) and lower sleep efficiency (coefficient = −0.177, P = 0.039). Negative mood was not predicted by TST (coefficient = −0.021, P = 0.112).

Following this, subjective sleep variables that were significant predictors of fatigue mean and variability were investigated, with and without negative mood as an additional predictor within the models, in order to examine the proportion of the total effect accounted for by negative mood. Table 4 shows these analyses for fatigue mean and variance outcomes.

Table 4.

Total, direct, and indirect effects for predictor-outcome relationships.

Within each of these models increased levels of negative mood on waking was related to increased mean fatigue across the day, and decreased variance in fatigue. The highest level of mediation (30.1%) was seen for the relationship between feeling refreshed and following-day fatigue variance.

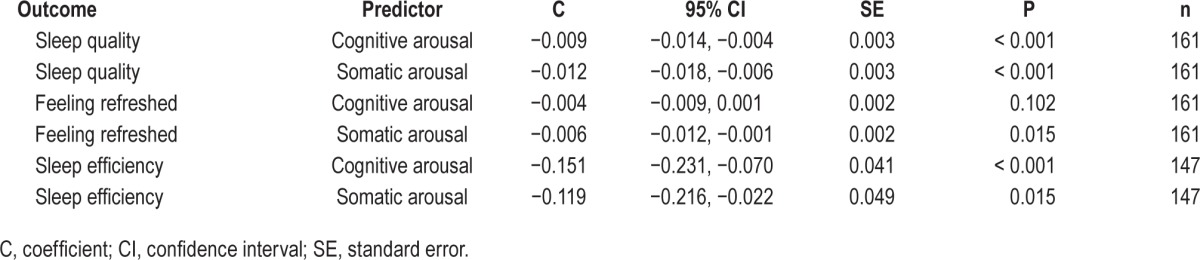

Predicting Subjective Sleep Using Presleep Variables

Presleep cognitive and somatic arousal were examined as predictors of sleep variables, which were found to be associated with following-day fatigue mean and variance, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Presleep cognitive and somatic arousal as predictors of subjective sleep variables.

Higher levels of cognitive and somatic arousal predicted poorer sleep quality and sleep efficiency. Higher levels of somatic arousal, but not cognitive arousal, predicted feeling less refreshed on waking.

DISCUSSION

Although sleep difficulties are commonly reported in CFS, the relationship between sleep and fatigue remains unclear. The current research builds on the limited previous research by using a daily diary approach, enabling a close examination of the link between sleep and next-day fatigue over a 6-day period, with comparisons made both between and within participants across study days. Importantly, this study demonstrated that subjective sleep quality, feeling refreshed on waking, and sleep efficiency were important predictors of following-day fatigue levels. In contrast, sleep variables estimated using actigraphy did not show a similar relationship with fatigue. These findings illustrate the importance of sleep perception in the experience of fatigue in CFS.

Presleep cognitive and somatic arousal were shown to predict subjective sleep quality and sleep efficiency, and somatic arousal also predicted perceiving sleep to be unrefreshing, a commonly reported difficulty in CFS. To our knowledge, this is the first time these associations have been observed in a CFS population and represent key findings given the apparent importance of subjective sleep in the experience of fatigue. Consistent with our observations, previous research in nonclinical populations has found that both cognitive and somatic arousal can have a negative effect on perceptions of sleep efficiency and quality.14 Although not measured in the current study, it remains possible that sleep related anxiety at bedtime contributed to high levels of presleep arousal. This in turn could have led to poor perceived sleep, due to increased attention to cues indicating wakefulness during the night, in line with processes hypothesized to play a role in insomnia.28 In support of this proposition, all participants in our sample held unhelpful beliefs about sleep within the clinical range, including fears that poor sleep will have a negative effect on daytime functioning. Future studies should, therefore, aim to employ specific measures of sleep related mentation proximal to the sleep onset period.

Low subjective sleep efficiency and perceiving sleep to be unrefreshing were both related to negative emotions on waking. In turn, negative mood on waking was shown to partially mediate the relationship between subjective sleep variables and next-day fatigue levels. Negative emotions may have influenced the experience of symptoms through a number of mechanisms. Anxiety or sadness following poor sleep may result in a perceived need to limit activity, and subsequently increase attention to fatigue, due to a lack of distraction from symptoms. High levels of anxiety about symptoms may also result in hypervigilance to fatigue. Any symptoms subsequently noticed may then be attributed to poor sleep, in line with similar processes hypothesized in insomnia.28 Of note, the mediational role of negative mood was modest, with 15% to 30% of the effect of perceived sleep on fatigue accounted for by negative mood. It is likely that additional factors such as symptom-focusing or activity levels also influence this relationship. Furthermore, ratings of negative mood in the current study were general in nature. A more specific measure of anxiety or hopelessness related to sleep, symptoms or functioning could have provided more information about the mediational role of these factors specifically. This is an area ripe for future exploration.

Importantly, the current study is the first to demonstrate the effect of sleep on variability in next-day fatigue in CFS, with unrefreshing sleep and lower sleep efficiency predicting reduced variability in fatigue across the following day. Negative mood partially mediated these relationships. In addition to increasing attention to symptoms, negative mood following un-refreshing and inefficient sleep may reduce variance in fatigue if individuals limit their activity levels due to feeling sad or hopeless, or because of anxiety about exacerbating symptoms. It has been found previously that some individuals with CFS can have particularly low levels of activity29 and that this can be related to beliefs that activity will increase fatigue.30,31 Limiting activity, therefore, can be seen as a safety behavior that may prevent individuals from disconfirming unhelpful beliefs about the effect of activity following a night of unrefreshing and inefficient sleep.28 In addition, reduced activity is likely to further impact mood and fatigue levels, increase physical deconditioning, and decrease sleep quality,32 feeding into the maintenance of the condition.9,33

Illness duration was also a significant predictor of variability in fatigue, with a longer duration related to fatigue being less variable across the day. One potential explanation for this finding is that unhelpful illness-related beliefs may become strengthened over the course of the illness through attentional and attributional biases, and because safety behaviors may prevent disconfirmation of these beliefs.9 As a result, expectations about fatigue being unchangeable, hopelessness related to this, and decreased activity and increased attention to symptoms, may result in a more fixed perception of symptoms across the day.

Taken together, the results of the current study indicate that a number of psychological factors are relevant to the experience of both sleep and subsequent fatigue. These include presleep cognitive and somatic arousal, perceptions of sleep quality and sleep efficiency, and negative mood on waking. Moreover, although not examined directly within the current study, attentional and attributional biases, and safety behaviors—such as decreasing activity following poor sleep—may also be relevant to sleep difficulties in this group, and should be investigated in future research. A related future direction is to examine the role of napping in the manifestation of fatigue. Although 52% of our sample napped at least once during the recording period, only 15% of total study days contained a nap episode, prohibiting meaningful and reliable analyses at the day level. In some patients, napping may operate as a maladaptive safety behavior, which could lead to reduced activity levels, heightened sleep related anxiety and impaired sleep-wake regulation, ultimately contributing to fatigue. Future work should, therefore, empirically assess these potential pathways.

Our findings have important clinical implications in that each of the identified factors can be targeted specifically within CBT for insomnia (CBT-I). CBT-I has previously been used to treat sleep difficulties in chronic pain conditions and can be effective in improving sleep quality and efficiency34 and in reducing daytime fatigue.35 This approach includes psycho-education about sleep, behavioral components including sleep restriction and stimulus control, relaxation strategies in order to target presleep arousal, sleep hygiene, and cognitive restructuring of unhelpful beliefs about sleep. Based on the findings of the current study, it seems likely that CBT-I would be helpful for patients with CFS who are experiencing sleep difficulties.

The current study has some limitations. While typical of prospective, high-resolution daily diary designs, our sample size was relatively modest. Recruitment through additional channels, beyond a single specialist service, may have enhanced overall numbers. For our mediation analyses, the mediator—negative mood on waking—was measured at the same timepoint as the subjective sleep variables. This allows for the possibility that negative mood impacted upon subjective ratings of sleep, rather than being as a result of poor perceived sleep. Consequently, the findings should be considered with this possibility in mind. In general, stronger relationships among subjective variables, relative to subjective-by-objective associations, may be explained in part through shared method variance. However, the consistency of our findings across different subjective sleep parameters, coupled with mechanistic support from existing CFS and insomnia literatures, speaks to the robustness of our findings and interpretation.

A further limitation relates to our use of actigraphy as our measure of objective sleep. It is well established, including in CFS samples,36 that actigraphy can underestimate SOL and WASO, and therefore overestimate SE. Interestingly, acti-graphic estimates of SOL in the current study were aligned with self-report (see Table 1), although marked discrepancies were observed in WASO and, correspondingly, sleep efficiency. Actigraphy does not provide measurement of sleep architecture and therefore we were not able to examine how specific sleep stages or microstructure may relate to next-day fatigue. Consequently, although the use of actigraphy allowed participants' sleep to be examined within their home setting, providing an ecologically valid estimation of objective sleep variables, findings should be viewed within the context of these limitations. Relatedly, we were only able to record actigraphy-defined sleep and daytime symptoms over 6 nights. Although this was deemed appropriate to allow testing of our research aims, and to limit participant burden (in a group who are highly fatigued), future replication studies should aim to recruit larger samples and measure sleep and symptoms over a 2-w period. Such a design may also help to define the contribution of occupational demands on sleep-fatigue relations, which we were not able to systematically examine in the present study.

Last, it was not feasible to screen all participants with polysomnography in order to exclude the possibility of additional sleep disorders, which may have influenced our findings given the high rates of undiagnosed sleep disorder pathology in CFS.37 However, in partial mitigation, all participants received a diagnosis of CFS in the context of a specialist service, where potential comorbidities are thoroughly interrogated, and the presence of additional sleep disorders was minimised by screening with the Brief Sleep Interview16 prior to participation. Future studies would benefit from thorough polysomno-graphic screening to definitively rule out clinically significant sleep disorder (e.g., sleep-related breathing disorder, periodic limb movement disorder).

In conclusion, this is the first study to examine the relationship between sleep and next-day fatigue in CFS using a daily diary approach. We found that subjective and not actigraphydefined sleep variables were associated with next-day fatigue and that negative mood partially mediated these relationships. We also showed that increased levels of presleep arousal are associated with subjectively impaired sleep. These findings suggest that sleep-specific interventions used within the insomnia field may be a helpful adjunct to existing CFS interventions. Further research should aim to examine the utility of such approaches within this patient group.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Kyle has consulted for Sleepio Ltd. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, Sharpe MC, Dobbins JG, Komaroff A International Chronic Fatigue Study Group. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:953–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nisenbaum R, Jones JF, Unger ER, Reyes M, Reeves WC. A population-based study of the clinical course of chronic fatigue syndrome. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:49. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jason LA, Richman JA, Rademaker AW, et al. A community-based study of chronic fatigue syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2129–37. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.18.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morriss RK, Wearden AJ, Battersby L. The relation of sleep difficulties to fatigue, mood and disability in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42:597–605. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)89895-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mariman A, Vogelaers D, Tobback E, Delesie L, Hanoulle I, Pevernagie D. Sleep in the chronic fatigue syndrome. Sleep Med Rev. 2013;17:193–9. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson M, Bruck D. Sleep abnormalities in chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a review. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:719–28. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perlis ML, Giles DE, Mendelson WB, Bootzin RR, Wyatt JK. Psychophysiological insomnia: the behavioural model and a neurocognitive perspective. J Sleep Res. 1997;6:179–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1997.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gotts ZM, Newton JL, Ellis JG, Deary V. The experience of sleep in chronic fatigue syndrome: a qualitative interview study with patients. Br J Health Psychol. 2016;21:71–92. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deary V, Chalder T, Sharpe M. The cognitive behavioural model of medically unexplained symptoms: a theoretical and empirical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:781–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gotts ZM, Ellis JG, Dreary V, Barclay N, Newton JL. The association between daytime napping and cognitive functioning in chronic fatigue syndrome. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aaron L, Burke M, Buchwald D. Overlapping conditions among patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and temporomandibular disorder. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:221–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicassio PM, Moxham EG, Schuman CE, Gevirtz RN. The contribution of pain, reported sleep quality, and depressive symptoms to fatigue in fibromyalgia. Pain. 2002;100:271–9. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myin-Germeys I, Oorschot M, Collip D, Lataster J, Delespaul P, van Os J. Experience sampling research in psychopathology: opening the black box of daily life. Psychol Med. 2009;39:1533–47. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang NKY, Harvey AG. Effects of cognitive arousal and physiological arousal on sleep perception. Sleep. 2003;27:69–78. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharpe MC, Archard LC, Banatvala JE, et al. A report-chronic fatigue syndrome: guidelines for research. J Royal Soc Med. 1991;84:118–21. doi: 10.1177/014107689108400224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson SJ, Nutt DJ, Alford C, et al. British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus statement on evidence-based treatment of insomnia, parasomnias and circadian rhythm disorders. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:1577–601. doi: 10.1177/0269881110379307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espie CA, Kyle SD, Hames P, Gardani M, Fleming L, Cape J. The Sleep Condition Indicator: a clinical screening tool to evaluate insomnia disorder. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004183. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morin CM, Vallieres A, Ivers H. Dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep (DBAS): validation of a brief version (DBAS- 16) Sleep. 2007;30:1547–54. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.11.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carney C, Edinger JD, Morin CM, et al. Examining maladaptive beliefs about sleep across insomnia patient groups. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, et al. Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res. 1993;17:147–53. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kushida CA, Chang A, Gadkary C, Guilleminault C, Carrillo O, Dement WC. Comparison of actigraphic, polysomnographic, and the subjective assessment of sleep parameters in sleep disordered patients. Sleep Med. 2001;2:389–96. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carney CE, Buysse DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. The consensus sleep diary: standardizing prospective sleep self-monitoring. Sleep. 2012;35:287–302. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang NKY, Goodchild CE, Sanborn AN, Howard J, Salkovskis PM. Deciphering the temporal link between pain and sleep in a heterogeneous chronic pain patient sample: a multilevel daily process study. Sleep. 2012;35:675–87. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nicassio PM, Mendlowitz DR, Fussell JJ, Petras L. The phenomenology of the pre-sleep state: the development of the pre-sleep arousal scale. Behav Res Ther. 1985;23:263–71. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(85)90004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buysse DJ, Thompson W, Scott J, et al. Daytime symptoms in primary insomnia: a prospective analysis using ecological momentary assessment. Sleep Med. 2007;8:198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bolger N, Laurenceau JP. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013. Intensive longitudinal methods: an introduction to diary and experience sampling research. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harvey AG. A cognitive model of insomnia. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40:869–94. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evering RMH, Van Weering MGH, Groothius-Oudshoorn KCGM, Vollenbroek-Hutten MMR. Daily physical activity of patients with the chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25:112–33. doi: 10.1177/0269215510380831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vercoulen JHMM, Bazelmans E, Swanink CMA, et al. Physical activity in chronic fatigue syndrome: assessment and its role in fatigue. J Psychiatr Res. 1997;31:661–73. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(97)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nijs J, Roussel N, Van Oosterwijck J, et al. Fear of movement and avoidance behaviour toward physical activity in chronic-fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia: state of the art and implications for clinical practice. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1121–9. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh NA, Clements KM, Fiatarone MA. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of exercise on sleep. Sleep. 1997;20:95–101. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark LV, White PD. The role of deconditioning and therapeutic exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) J Ment Health. 2005;14:237–52. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Currie SR, Wilson KG, Pontefract AJ, DeLaplante L. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of insomnia secondary to chronic pain. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:407–16. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez MP, Miro E, Sanchez AI, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia and sleep hygiene in fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. J Behav Med. 2014;37:683–97. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9520-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Creti L, Libman E, Baltzan M, Rizzo D, Bailes S, Fichten CS. Impaired sleep in chronic fatigue syndrome: how is it best measured? J Health Psychol. 2010;15:596–607. doi: 10.1177/1359105309355336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gotts ZM, Deary V, Newton J, Van der Dussen D, De Roy P, Ellis JG. Are there sleep-specific phenotypes in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome? A cross-sectional polysomnography analysis. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002999. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]