ABSTRACT

Immunoassays are currently needed to quantify Loa loa microfilariae (mf). To address this need, we have conducted proteomic and bioinformatic analyses of proteins present in the urine of a Loa mf-infected patient and used this information to identify putative biomarkers produced by L. loa mf. In total, 70 of the 15,444 described putative L. loa proteins were identified. Of these 70, 18 were L. loa mf specific, and 2 of these 18 (LOAG_16297 and LOAG_17808) were biologically immunogenic. We developed novel reverse luciferase immunoprecipitation system (LIPS) immunoassays to quantify these 2 proteins in individual plasma samples. Levels of these 2 proteins in microfilaremic L. loa-infected patients were positively correlated to mf densities in the corresponding blood samples (r = 0.71 and P < 0.0001 for LOAG_16297 and r = 0.61 and P = 0.0002 for LOAG_17808). For LOAG_16297, the levels in plasma were significantly higher in Loa-infected (geometric mean [GM], 0.045 µg/ml) than in uninfected (P < 0.0001), Wuchereria bancrofti-infected (P = 0.0005), and Onchocerca volvulus-infected (P < 0.0001) individuals, whereas for LOAG_17808 protein, they were not significantly different between Loa-infected (GM, 0.123 µg/ml) and uninfected (P = 0.06) and W. bancrofti-infected (P = 0.32) individuals. Moreover, only LOAG_16297 showed clear discriminative ability between L. loa and the other potentially coendemic filariae. Indeed, the specificity of the LOAG_16297 reverse LIPS assay was 96% (with a sensitivity of 77%). Thus, LOAG_16297 is a very promising biomarker that will be exploited in a quantitative point-of-care immunoassay for determination of L. loa mf densities.

IMPORTANCE

Loa loa, the causative agent of loiasis, is a parasitic nematode transmitted to humans by the tabanid Chrysops fly. Some individuals infected with L. loa microfilariae (mf) in high densities are known to experience post-ivermectin severe adverse events (SAEs [encephalopathy, coma, or death]). Thus, ivermectin-based mass drug administration (MDA) programs for onchocerciasis and for lymphatic filariasis control have been interrupted in parts of Africa where these filarial infections coexist with L. loa. To allow for implementation of MDA for onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis, tools that can accurately identify people at risk of developing post-ivermectin SAEs are needed. Our study, using host-based proteomics in combination with novel immunoassays, identified a single Loa-specific antigen (LOAG_16297) that can be used as a biomarker for the prediction of L. loa mf levels in the blood of infected patients. Therefore, the use of such biomarker could be important in the point-of-care assessment of L. loa mf densities.

INTRODUCTION

Loiasis, a tropical disease caused by the filarial parasite Loa loa (commonly known as the African eyeworm), affects approximately 13 million people in Central and West Africa, with the highest prevalences found in Angola, Cameroon, Gabon, Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Nigeria. Like most of the blood-borne filariae, the overwhelming majority of L. loa infections are clinically asymptomatic; moreover, L. loa has been viewed as a relatively unimportant infection (1, 2). However, L. loa has gained prominence in the past 20 years because of the serious adverse events (SAEs) associated with ivermectin distribution as part of mass drug administration (MDA) campaigns targeted toward elimination of onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis (LF) (3–5). These post-ivermectin SAEs, which include irreversible neurologic complications and deaths, have typically been observed in individuals with greater than 30,000 L. loa microfilariae (mf)/ml of blood (5). Consequently, ivermectin-based MDA programs have been delayed or paused in parts of Africa where L. loa is coendemic with either LF or onchocerciasis (6). The use of alternative “safer” treatment options (7–10) for onchocerciasis and LF has been proposed in regions of L. loa coendemicity, but none has been found to be practical and/or efficacious. The strategy that has gained the most traction in these settings has been termed “test and (not) treat” (TNT), whereby those at risk for post-ivermectin SAEs are identified and excluded from ivermectin-based MDA programs. Such a TNT strategy, however, requires a rapid and point-of-care (POC) test allowing for the quantification of L. loa mf loads.

Currently, the definitive identification and quantification of L. loa mf can be made either by the traditional microscopic methods using calibrated stained slide-based methods (11, 12) or by using quantitative PCR (qPCR) tests, the latter adding an additional level of sensitivity (13). However, both of these methods are time intensive, relatively expensive (qPCR), or impractical for rapid testing at the POC. Recently, a mobile phone-based video microscopy system (CellscopeLoa) has been developed as a POC tool that allows rapid and accurate counting of L. loa mf (14). However, such a device is not as precise as other methods when assessing low L. loa mf densities (<150 mf/ml of blood) because of sampling limitations, and manufacturing for widespread use is lacking. Therefore, a POC quantitative immunoassay for mf-derived antigens could provide a second-generation POC assessment tool.

During their life cycle, L. loa parasites have five distinct morphological stages in their human and invertebrate (Chrysops) hosts (15). The mf, released by adult female worms into the human circulation, produce large and presumably measurable amounts of proteins and glycoproteins (16–18), either through excretion or active secretion (so-called “ES products”). Studies with Brugia malayi indicate that relatively more ES products are produced by the mf by any of the other stages (adult and other larval stages) of the parasite in vitro (19). However, unlike B. malayi, for which the life cycle can be maintained in animal models, providing large numbers of parasites of all stages, the biology of L. loa mf (e.g., their proteome/secretome) has been difficult to explore because parasite material is limited as it must be obtained from infected human subjects.

We postulated that certain L. loa parasite antigens secreted or excreted into the human bloodstream might not be fully reabsorbed following filtering by the renal glomeruli and could thereby be concentrated in the urine of Loa-infected individuals. Studies have shown that urine is a sample source of high importance for biomarker discovery because it is easily available, can be collected noninvasively in large quantities (20, 21), and, from a protein point of view, is much less complex than human serum or plasma. In the present study, utilizing a nontargeted (shotgun) nanobore reversed-phase liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (RPLC-MS/MS) proteomic approach, we attempted to identify L. loa mf proteins present in the urine of Loa-infected patients that could be used as the basis of quantitative immunoassays for the detection of L. loa mf-specific biomarkers in either plasma/serum or in urine.

RESULTS

Specificity of identified and selected proteins.

Mass spectrometry analyses of urine samples from an L. loa-infected individual resulted in the identification of spectra matching those of 70 L. loa proteins, of which 18 proteins were detectable by at least 2 unique peptides and not present in normal uninfected urine (Table 1). All 18 proteins were identified to be L. loa mf proteins. Their corresponding mRNA expression (22) ranged from 2.07 to 3,841.10 fragments per kilobase per million (FPKM). Eight (44.4%) of the 18 L. loa urine-specific proteins were annotated as “hypothetical” proteins with unknown function (Table 1).

TABLE 1 .

Details of L. loa mf-specific proteins identified in urine of patientsa

| Protein ID no. | Description | Peptide count | Mol mass (kDa) | FKPM | Homology to human |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E value | % coverage | Homologue? | |||||

| LOAG_00073 | Heat shock protein 90 | 2 | 69.4 | 3,841.1 | 0E+00 | 99 | Yes |

| LOAG_01395 | WD repeats and SOF1 domain-containing protein | 2 | 51.0 | 101.3 | 5E−174 | 97 | Yes |

| LOAG_01611 | Hypothetical protein | 2 | 64.5 | 29.8 | 1E−85 | 74 | Yes |

| LOAG_02628 | Low-density lipoprotein receptor repeat class B-containing protein | 2 | 196.0 | 33.7 | 4E−129 | 86 | Yes |

| LOAG_03988 | Hypothetical protein | 2 | 54.0 | 152.3 | 2E−08 | 92 | Yes |

| LOAG_04876 | Peptidase M16 inactive domain-containing protein | 2 | 47.4 | 40.7 | 2E−43 | 93 | Yes |

| LOAG_05583 | U4/U6 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein hPrp4 | 2 | 56.6 | 43.4 | 2E−157 | 99 | Yes |

| LOAG_05701 | 14-3-3-like protein 2 | 2 | 28.3 | 2,392.0 | 1E−147 | 94 | Yes |

| LOAG_05915 | Hypothetical protein | 2 | 104.3 | 14.7 | 2E−02 | 33 | No |

| LOAG_06631 | Troponin | 2 | 171.1 | 8.8 | 1E−05 | 13 | Yes |

| LOAG_09325 | Hypothetical protein | 2 | 33.0 | 68.3 | 1E−13 | 27 | Yes |

| LOAG_10011 | Hypothetical protein | 2 | 13.6 | 3,257.3 | 7E−66 | 98 | Yes |

| LOAG_16297 | Hypothetical protein | 2 | 14.3 | 0.4 | 5E−04 | 67 | No |

| LOAG_17249 | Pyruvate kinase | 2 | 59.0 | 609.7 | 0E+00 | 99 | Yes |

| LOAG_17808 | PWWP domain-containing protein | 2 | 69.8 | 13.9 | 9E−04 | 5 | No |

| LOAG_18456 | Cullin-associated NEDD8-dissociated protein 1 | 2 | 124.1 | 45.5 | 0E+00 | 98 | Yes |

| LOAG_18552 | Hypothetical protein | 2 | 106.5 | 2.1 | 1E−03 | 44 | No |

| LOAG_19057 | Hypothetical protein | 3 | 30.2 | 89.2 | 5E−128 | 77 | Yes |

Proteins that do not share significant sequence homology to human proteins are highlighted in bold. FPKM represents the relative mRNA expression level obtained using transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) (22).

Further filtering the data for proteins with little or no sequence homology with human proteins shortlisted four L. loa proteins: LOAG_05915, LOAG_16297, LOAG_17808, and LOAG_18552 (Table 1). These four proteins were then assessed for having homologues in the other filariae sequenced to date—B. malayi, Wuchereria bancrofti, and Onchocerca volvulus (Table 2). As can be seen, LOAG_05915, LOAG_17808, and LOAG_18552 share significant sequence homology W. bancrofti, B. malayi, and O. volvulus proteins, while LOAG_16297, a small 14-kDa hypothetical protein, showed no homology to proteins of any of these filarial parasites nor to any nematode for which genomic sequences are available.

TABLE 2 .

Specificity of the four downselected L. loa mf proteins

| Protein ID (accession no.) | Immunogenic peptide sequence |

B. malayi |

W. bancrofti |

O. volvulus |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % identity | E value | % identity | E value | % identity | E value | ||

| LOAG_05915 (EFO22569.1) | CMRDKYRDTENE | 76 | 0 | 65 | 0 | No hit | |

| CLDDEKEQYNKNL | |||||||

| LOAG_18552 (EJD74082.1) | CEEKQNRNEKPANGD | No hit | 87 | 0 | 42 | 0 | |

| CEQEKLEKPKSKKPNP | |||||||

| LOAG_17808 (EJD74956.1) | CEGENKRDGKRRMDKSP | 91 | 0 | 91 | 0 | No hit | |

| CRPFDDERNSYDKNGN | |||||||

| LOAG_16297 (EFO12236.1) | CVETRKYENRK | No hit | No hit | No hit | |||

| CDSDTGNRNDESYKFKQ | |||||||

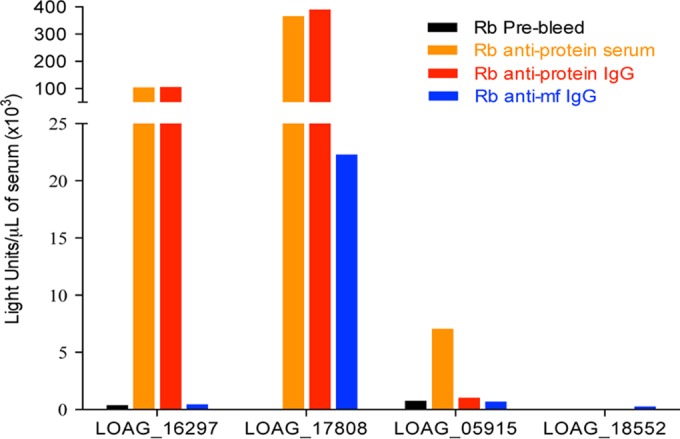

Immunogenicities of the four selected L. loa proteins.

The immunogenicities of the protein antigens were assessed using hyperimmune rabbit antisera in a standard luciferase immunoprecipitation system (LIPS) assay. As shown in Fig. 1, there was minimal reactivity with the respective prebleed sera and robust reactivity with the hyperimmune sera (and their purified IgG) from two of the four fusion proteins, LOAG_17808 and LOAG_16297. In addition, the LOAG_17808 fusion protein was also recognized by purified IgG antibodies raised against L. loa somatic mf antigen (Fig. 1).

FIG 1 .

Reactivities of the four fusion proteins to their specific antibodies. Antisera (orange) raised against the two most immunogenic peptides of each protein, IgG purified from those antisera (red), and purified IgG anti-L. loa mf somatic antigen (blue) were used to test reactivities to the four fusion proteins. “Rb prebleed” antisera (black) are antisera collected prior to immunization. The protein names are indicated under the x axis.

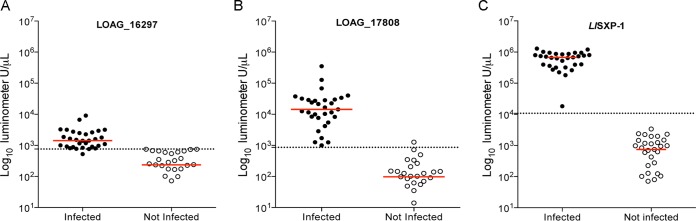

To evaluate the reactivity of these proteins in humans, sera/plasma from L. loa-infected patients and uninfected control subjects were used and compared to the reactivity to L. loa SXP-1, a previously described L. loa antigen (23). As expected, healthy-control samples had very low signals, with median anti-LOAG_16297, anti-LOAG_17808, and anti-SXP-1 antibody titers of 236, 97, and 746 light units (LU), respectively (Fig. 2). For L. loa-infected patients, the median values were 6 times higher for LOAG_16297 (1,423 LU), 148 times higher for LOAG_17808 (14,317 LU), and 905 times higher for SXP-1 (674,990 LU) than the median titers of the uninfected healthy controls. The differences between L. loa-infected patients and uninfected controls were significant for all tested fusion proteins (P < 0.0001). In addition, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis shows that the two L. loa mf antigens were able to accurately distinguish Loa-infected from Loa-uninfected individuals: LOAG_16297 with 96.7% sensitivity and 100% specificity, using a threshold of 760 LU (Fig. 2A), and LOAG_17808 with 100% sensitivity and 96.7% specificity, using a threshold of 862 LU (Fig. 2B). In comparison, L. loa SXP-1 showed 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity using a threshold of 10,785 LU on the same set of 31 patients and 31 controls (Fig. 2C).

FIG 2 .

Immunogenicity of LOAG_16297, LOAG_17808, and SXP-1 in humans. The levels of IgG specific to LOAG_16297 (A), LOAG_17808 (B), and SXP-1 (C) were assessed by LIPS assay, and light units (LU) were compared between Loa-infected subjects and uninfected controls. The horizontal red solid line represents the median level for each group, and the horizontal black dotted line indicates the threshold of sensitivity/specificity of the assay determined by ROC analysis. Each individual is represented by a single dot, with closed circles used for the Loa-infected individuals and open circles for the uninfected individuals.

Competitive LIPS assay results.

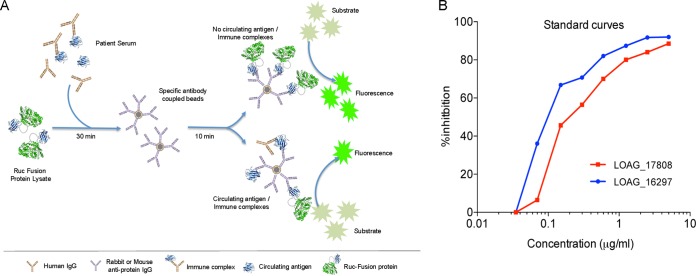

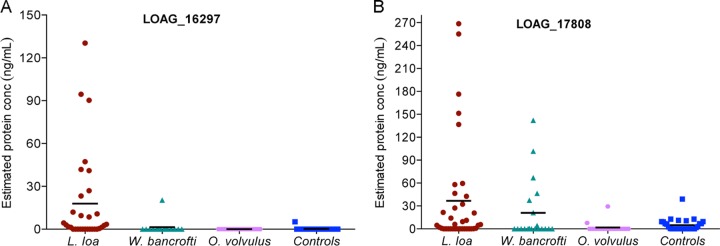

The ability to identify LOAG_16297 and LOAG_17808 in an antigen detection system was next tested using a heretofore-undescribed competitive LIPS assay (Fig. 3A) in L. loa-, W. bancrofti-, and O. volvulus-infected individuals and uninfected healthy controls. Using pooled human AB serum spiked with increasing concentrations of the appropriate antigen, we were able to generate standard curves that allowed us to relate the percentage of inhibition in the competitive LIPS assay to the antigen concentration present in the sera (Fig. 3B). We then used these standard curves to quantitate the levels of circulating protein in the serum of Loa-infected patients and in the control groups. For LOAG_16297 (Fig. 4A), the geometric mean level of detectible protein in serum/plasma was 17.88 ng/ml in Loa-infected subjects, whereas it was negligible in W. bancrofti- and O. volvulus-infected subjects and in uninfected subjects. Using a cutoff based on an ROC analysis (5 ng/ml), we can see that there were measurable antigen levels in 12/26 microfilaremic Loa-infected individuals compared to 0/5 amicrofilaremic Loa-infected, 0/31 uninfected (P < 0.0001), 0/15 O. volvulus-infected (P = 0.004), and 1/15 W. W. bancrofti-infected (P = 0.03) individuals. For LOAG_17808 (Fig. 4B), the geometric mean levels of protein were 36.68 ng/ml in Loa-infected, 21.04 ng/ml in W. bancrofti-infected, and 1.86 ng/ml in O. volvulus-infected individuals and 4.97 ng/ml in uninfected individuals. Again using ROC analysis (with an upper threshold of 39 ng/ml), there were detectible LOAG_17808 levels in 9/26 microfilaremic Loa-infected subjects for 0/5 in the amicrofilaremic Loa-infected group, 0/31 in the uninfected control group (P = 0.002), 0/15 in the O. volvulus-infected group (P = 0.02), and 4/15 in the W. bancrofti-infected group (P = 0.9).

FIG 3 .

Principle of the antigen LIPS assay and relationship between the percentage of protein inhibition and amount of protein. (A) Schematic of the general steps involved in competitive LIPS antigen detection in which the Renilla luciferase (Ruc) fusion constructs of the antigen of interest are incubated with serum containing unfused antigen. These antigens are then immobilized on agarose beads containing antigen-specific IgG. After washing, the amount of specific antigen present is determined by the inhibition of the Ruc fusion construct by the unfused antigen after addition of luciferase substrate. Panel B shows the percentage of inhibition as a function of spiked recombinant protein in human AB serum for LOAG_16297 (blue) and LOAG_17808 (red).

FIG 4 .

Detection of LOAG_16297 and LOAG_17808 in plasma samples by LIPS assay. The quantities of LOAG_16297 (A) and LOAG_17808 (B) were estimated for 31 L. loa-infected (red), 15 W. bancrofti-infected (green), and 15 O. volvulus-infected (purple) individuals and 25 uninfected (blue) individuals, extrapolating from standard curves as represented in Fig. 3B. The horizontal solid black line in each group indicates the geometric mean in nanograms per milliliter of protein, and each value is represented by an individual dot.

LOAG_16297 and LOAG_17808 LIPS assay performance compared to microscopy.

To further assess the performance of the LOAG_16297- and LOAG_17808-based LIPS antigen detection assays, optimized competitive LIPS assays were run using plasma samples from 26 Loa microfilaremic (Loa mf+) subjects with a range of mf counts and from 25 healthy (uninfected) individuals (Table 3). Considering microcopy to be the “gold standard” for L. loa mf quantification, the LOAG_16297 antigen LIPS assay had a sensitivity of 76.9% (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 56.3 to 91.0%), a specificity of 96.0% (95% CI, 79.6 to 99.9%), a positive predictive value (PPV) of 95.2% (95% CI, 76.2 to 99.9%), and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 80% (95% CI, 61.4 to 92.2%). For the LOAG_17808 competitive LIPS assay, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were 80.7 (95% CI, 60.6 to 93.5%), 37.5 (95% CI, 18.8 to 59.4%), 58.3% (95% CI, 40.8 to 74.5%), and 64.3% (95% CI, 35.1 to 87.2%).

TABLE 3 .

Performance of L. loa mf-specific proteins on clinical samples using a LIPS competitive assaya

| LIPS assay type | Status | No. of samples: |

% sensitivity (95% CI) | % specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mf+ | mf− | ||||||

| LOAG_16297 | Positive | 20 | 1 | 76.9 (56.3–91.0) | 96.0 (79.6–99.9) | 95.2 (76.2–99.9) | 80.0 (61.4–92.3) |

| Negative | 6 | 24 | |||||

| LOAG_17808 | Positive | 21 | 15 | 80.7 (60.6–93.5) | 37.5 (18.8–59.4) | 58.3 (40.8–74.5) | 64.3 (35.1–87.2) |

| Negative | 5 | 9 | |||||

PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value. The 95% confidence interval (95% CI) is indicated for each parameter.

Correlation between the amount of LOAG_16297 antigen and the number of microfilariae.

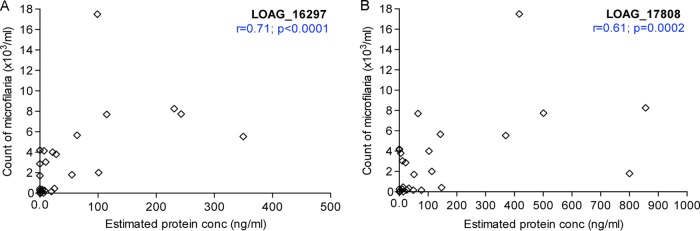

To evaluate if the levels of antigen circulating in the plasma of Loa-infected individuals with a range of mf counts were correlated with the density of mf, Spearman’s rank correlation was performed between the plasma concentrations of the LOAG_16297 and LOAG_17808 proteins and the corresponding counts of L. loa mf as determined by microscopy (Fig. 5). As can be seen, there were significant positive correlations for LOAG_16297 (r = 0.71, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 5A) and for LOAG_17808 (r = 0.61, P = 0.0002) (Fig. 5B).

FIG 5 .

Correlation between the quantities of detected antigen (represented by detected protein in L. loa mf-infected individuals) and L. loa mf count.

DISCUSSION

L. loa infection has recently gained prominence because of the SAEs occurring after ivermectin administration in some individuals harboring high L. loa mf densities (4, 5). Most of the currently available tools and methods (11, 13, 23, 24) that are being used to quantify L. loa mf are impractical for POC field-testing. Developing a quantitative immunoassay for L. loa mf that could be used for field screening to identify individuals at high risk of SAE would be of great benefit to MDA programs. Thus, we have identified 18 proteins present only in L. loa mf-infected urine by using a high-throughput RPLC-MS/MS proteomic approach. We then developed antigen-based competitive LIPS assays for the 2 (LOAG_16297 and LOAG_17808) that were immunogenic and highly (and/or relatively) specific to L. loa mf. One of these, LOAG_16297 showed excellent diagnostic performance and has great promise for a potential field use as a POC diagnostic tool.

The presence of parasite proteins in urine should be a surrogate for their availability in the circulation and, therefore, should provide an accurate source for biomarker discovery useful for disease diagnosis (25). In our study, only 18 were found exclusively in the urine of the Loa-infected patient compared to urine from uninfected individuals, suggesting some promiscuity in this proteomic approach. This number of urine-identified proteins was relatively low considering the total number of putative L. loa proteins (15,444) (22). That is certainly due to the fact that there are many fewer proteins in urine than in the plasma (26), the majority of proteins found in the blood being reabsorbed through the renal glomeruli. We also cannot exclude the role played by variability among the analytes in the urine (27), factors related to the MS/MS instrument itself (28), or the fact that so many Loa proteins had similar human sequences. Therefore, it would be more advantageous to perform proteomics of urine samples from multiple Loa-infected individuals. Nevertheless, the data gleaned from one urine sample from an infected individual allowed us to identify potential biomarker candidates and then validate the most important ones.

Most of the identified Loa-specific urine proteins (14/18) have orthologues in humans. Among the four Loa mf proteins unrelated to human proteins, only two, LOAG_16297 and LOAG_17808, could be studied closely as they were immunogenic in rabbits. In addition, antibodies raised against L. loa crude somatic mf antigen recognized LOAG_17808 and LOAG_16297 (to a lesser degree), suggesting that they make up a significant fraction of the mf-specific antigen mix. Furthermore, antibodies to both LOAG_16297 and LOAG_17808 were present in L. loa-infected patients. Although not the main purpose of the present study, these antigens show promise in an antibody-based immunoassay with sensitivities and specificities similar to or close to what has been observed with L. loa SXP-1 (23, 29) antibody profiling for L. loa diagnosis.

In general, antibody-based assays often are unrelated to parasite burden, and a correlation between antibody level and parasite density is likely to be difficult (if not impossible). In addition, specific antibodies cannot distinguish between previous and new infections and often persist indefinitely after treatment or exposure (29). Antigen-based assays are then the sine qua non for diagnosis of infectious diseases. Thus, we developed methods for rapidly testing the validity of such assays using a single antibody specific for the protein in question and a mammalian-expressed recombinant protein that could be used without purification. Such an assay, termed reverse (or competitive) LIPS, relies on the ability of the antigen(s) in serum (or other biological samples) to inhibit a fixed concentration of the same protein that is luciferease fused (Fig. 3A). In addition to its simplicity, the competitive LIPS assay could identify L. loa-infected patients and quantify the L. loa mf level rapidly and with good accuracy. Only 45 to 60 min of total processing time (including preparation and wash times) per 94 plasma samples is needed compared to hours for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs). Moreover, ELISAs for antigen often require at least two different antibodies (e.g., directed against different epitopes of the same protein), a requirement that often cannot be satisfied. The presumed increased sensitivity of the LIPS-based system is likely due to the assay performance in solution, our ability to detect many more conformational epitopes than a standard solid-phase ELISA (23), and the fact that highly purified recombinant antigen is not needed.

In the present study, we have shown that both circulating LOAG_16297 and LOAG_17808 antigens can be detected in some plasma of Loa-infected individuals. Interestingly and more in line with its potential utility as a POC method to identify those at risk for SAEs following ivermectin, there was a significant positive relationship between the amounts of LOAG_16297 and LOAG_17808 proteins detected in Loa-infected samples and the mf levels in blood of the same samples. Furthermore, the assay to detect LOAG_16297 described herein showed the best correlation to mf data and had the best specificity, PPV and NPV (Fig. 5 and Table 3). The lower specificity of the assay for LOAG_17808 is not surprising since the protein shares 91% sequence identity to a PWWP domain protein of W. bancrofti (and other filariae).

There are currently no commercial products available using LIPS-based tests. In addition, the development of a LIPS assay for a POC use may be difficult (if not impossible) mainly because of the high cost of the LIPS platform. Nevertheless, the use of LIPS has allowed us to validate a single identified antigen (LOAG_16297) as being quantitative and specific. With a potential candidate biomarker in hand, we hypothesize that generation of monoclonal antibodies for use in a cheaper standard antigen capture or lateral-flow immunoassay can be configured for POC testing. The use of monoclonal antibodies will increase the affinity of the searched antigens to their specific antibodies and likely improve the performance of the assay.

In summary, we have used an untargeted protein profiling approach (RPLC-MS/MS) to discover 18 new putative biomarkers of L. loa mf infection in the urine of a microfilaremic patient with L. loa. Among them, one immunogenic and highly L. loa mf-specific protein, LOAG_16297, can be detected in plasma/serum in a competitive LIPS assay format, with the amounts being detected correlating well with the quantity of L. loa mf found in the peripheral blood. Therefore, the use of LOAG_16297 as a biomarker could be important in a POC assessment tool to be used as the basis of an effective TNT strategy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and samples.

Samples were collected from subjects as part of registered protocols approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases for the filaria-infected patients (NCT00001345) and for healthy donors (NCT00090662). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Urine samples from one microfilaremic (17,000 mf/ml) L. loa-infected patient assessed at the NIH Clinical Center and one normal North American donor (who had never traveled outside the United States) were used for the profiling of specific L. loa mf proteins by RPLC-MS/MS.

Plasma samples used to validate the utility of potential biomarkers were from L. loa-infected individuals (n = 31 [26 microfilaremic and 5 amicrofilaremic]). Samples used as controls included those from subjects with W. bancrofti infection (mf+; n = 15) from India and the Cook Islands (both nonendemic for L. loa), subjects with O. volvulus infection (mf+; n = 15) from Ecuador (nonendemic for L. loa), and those from North America who had no history of exposure to filariae or other helminths and who had never traveled outside North America (n = 31). The parasitological diagnosis of all infections was made based on the demonstration of mf in the blood (for W. bancrofti and L. loa) or in the skin (for O. volvulus) using standard techniques (11, 30) or by finding adult parasites in the tissues (e.g., the eye for L. loa).

Sample preparation prior to mass spectrometric analysis.

Urine samples were processed according to a workflow adapted from Nagaraj et al. (31). Briefly, urine samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 4°C and the supernatant was concentrated using a spin filter with a molecular mass cutoff of 3 kDa. Proteins were precipitated by acetone precipitation and subsequently treated in 10 mM Tris-HCl at 95°C for 5 min. The samples were then reduced, alkylated, and double digested with Lys-C in combination with trypsin overnight at 37°C. Tryptic peptides were further desalted, lyophilized, reconstituted in 25% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid, and further fractionated using strong cation exchange (SCX) chromatography. The SCX fractions of the urine samples were pooled into 32 fractions, lyophilized, and reconstituted in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to be analyzed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

Nanobore RPLC-MS/MS.

Nanobore reversed-phase liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (RPLC-MS/MS) was performed using an Agilent 1200 nanoflow LC system coupled online with an LTQ Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer. The RPLC column (75-µm inside diameter [i.d.] by 10 cm) was slurry packed in-house with 5-µm, 300-Å pore-size C18 stationary phase into fused silica capillaries with a flame-pulled tip. The mass spectrometer was operated in a data-dependent mode in which each full MS scan was followed by twenty MS/MS scans, wherein the 20 most abundant molecular ions were dynamically selected for collision-induced dissociation (CID) using a normalized collision energy of 35%.

Protein identification and quantification.

The RPLC-MS/MS data were searched using SEQUEST through Bioworks interface against an L. loa database downloaded from the Broad Institute (version 2.2). Dynamic modifications of methionine oxidation as well as fixed modification of carbamidomethyl cysteine were also included in the database search. Only tryptic peptides with up to two missed cleavage sites meeting the following specific SEQUEST scoring criterion were considered legitimate identifications: delta correlation (ΔCn) of ≥0.1 and charge-state-dependent cross-correlation (Xcorr) of ≥1.9 for [M+H]1+, ≥2.2 for [M + 2H]2+, and ≥3.5 for [M + 3H]3+.

Transcriptomics data.

mRNA expression levels (putative proteins) of the mf state of L. loa were obtained using RNAseq as part of the L. loa genome project previously described (22).

Protein/peptide selection for immunoassays.

L. loa mf proteins identified only in the infected urine (absent in the uninfected urine) were downselected for immunoassays based on comparison of sequence homologies against human proteins and those of L. loa and other related filarial species (B. malayi, O. volvulus, and W. bancrofti) or any other relevant nematode for which genome is available.

Proteins that showed no or little homology to non-Loa sequences were selected for identification of immunogenic peptides using Protean (Lasergene Suite). Among these, we chose the 2 peptides that were potentially the most immunogenic and Loa specific (i.e., with no significant hit to human or other filarial nematodes) per protein. These peptides were synthesized by the NIAID Peptide Facility as unconjugated free peptides and conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH), the latter used to produce specific polyclonal antibodies in rabbits.

Generation of rabbit polyclonal antibodies.

KLH-conjugated peptides were used to raise polyclonal antisera in rabbits using standard protocols as previously described (32). In addition, polyclonal antisera were raised against a somatic extract of L. loa mf using the same standardized protocols. After assessment of the reactivity of each of the antisera to its appropriate free peptide by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), the IgG was purified from the sera using protein A/G (Pierce, Rockford, IL) columns. These purified IgG antibodies were used as capture antibodies in the luciferase immunoprecipitation system (LIPS) assay for antigen detection (see below).

Fusion proteins and COS-1 cell transfection.

Fusion proteins were made for each of the in silico selected proteins by cloning the full-length gene expressing the protein of interest into a FLAG-epitope-tagged mammalian Renilla reniformis luciferase (Ruc)-containing expression vector, pREN2 (33). Extracts (lysates) containing the light-emitting Ruc-antigen fusions were prepared from 100-mm2 dishes of 48-h-transfected COS-1 cells as previously described (33, 34) and frozen until use for LIPS.

LIPS-based antibody and antigen detection systems.

For evaluation of antibody titers, a standard LIPS antibody-based assay was used (23, 34, 35). Briefly, 100 µl of the assay master mix (20 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100), 1 µl of undiluted plasma/serum, and 2 × 106 light units (LU) of the Ruc-antigen fusion protein were added to each well of a 96-well polypropylene plate. This plate was then incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Next, 7 µl of a 30% suspension of Ultralink protein A/G beads (Pierce, Rockford, IL) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was added to the bottom of a 96-well high-throughput-screening filter plate (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The 100-µl antigen-antibody reaction mixture from each microtiter well of the 96-well polypropylene plate was then transferred to the well of the filter plate, which was further incubated for 10 to 15 min at room temperature. The filter plate containing the mixture was then applied to a vacuum manifold. The retained protein A/G beads were washed with the assay master mix and with PBS (pH 7.4), the plate was blotted, and the LU were measured in a Berthold LB 960 Centro microplate luminometer, using a coelenterazine substrate mixture (Promega, Madison, WI).

For quantification of antigens, the original LIPS antibody-testing format was modified for use in a competitive LIPS assay (Fig. 3A). Having first coupled the purified antigen-specific IgG to Ultralink beads (Pierce, Rockford, IL), 5 µl of a 50% suspension (in PBS) of these beads (specific IgG-Ultralink beads) was added to the bottom of a 96-well filter plate. Glycine-treated plasma/serum (36) diluted 1/5 was added to the beads for 30 min at room temperature. Then, an optimized number of specific LU of Ruc-antigen fusions was added in each well and the mixture was incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Specific IgG-Ultralink beads were washed with the assay master mix and then with PBS. The plate was blotted, and LU were measured with a Berthold LB 960 Centro microplate luminometer. The percentage of inhibition was calculated for each sample, and the quantity of specific protein in each sample was estimated by using a standard curve designed using known concentrations of each protein in 1/5 diluted human AB serum (Fig. 3B).

All samples were run in duplicate. All LU data presented were corrected for background by subtracting the LU values of beads incubated with Ruc-antigens but no serum.

Statistical analysis.

Figures and statistical analyses, including specificity and sensitivity calculations (ROC analysis) and correlations (Spearman’s rank), were performed using Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Fischer’s exact test was used to compare the percentages of positivity between groups, and the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was used to estimate differences in amounts of antigen between two groups. All differences were considered significant at the P < 0.05 level.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all the volunteers who participated in this study.

This article is a direct contribution from a Fellow of the American Academy of Microbiology.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the Division of Intramural Research (DIR) of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Citation Drame PM, Meng Z, Bennuru S, Herrick JA, Veenstra TD, Nutman TB. 2016. Identification and validation of Loa loa microfilaria-specific biomarkers: a rational design approach using proteomics and novel immunoassays. mBio 7(1):e02132-15. doi:10.1128/mBio.02132-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hotez PJ, Molyneux DH, Fenwick A, Kumaresan J, Sachs SE, Sachs JD, Savioli L. 2007. Control of neglected tropical diseases. N Engl J Med 357:1018–1027. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra064142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metzger WG, Mordmüller B. 2014. Loa loa—does it deserve to be neglected? Lancet Infect Dis 14:353–357. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70263-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boussinesq M, Gardon J, Gardon-Wendel N, Kamgno J, Ngoumou P, Chippaux JP. 1998. Three probable cases of Loa loa encephalopathy following ivermectin treatment for onchocerciasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 58:461–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chippaux JP, Boussinesq M, Gardon J, Gardon-Wendel N, Ernould JC. 1996. Severe adverse reaction risks during mass treatment with ivermectin in loiasis-endemic areas. Parasitol Today 12:448–450. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(96)40006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardon J, Gardon-Wendel N, Demanga-Ngangue, Kamgno J, Chippaux JP, Boussinesq M. 1997. Serious reactions after mass treatment of onchocerciasis with ivermectin in an area endemic for Loa loa infection. Lancet 350:18–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)11094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zouré HG, Wanji S, Noma M, Amazigo UV, Diggle PJ, Tekle AH, Remme JH. 2011. The geographic distribution of Loa loa in Africa: results of large-scale implementation of the rapid assessment procedure for loiasis (RAPLOA). PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5:e1210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabi TE, Befidi-Mengue R, Nutman TB, Horton J, Folefack A, Pensia E, Fualem R, Fogako J, Gwanmesia P, Quakyi I, Leke R. 2004. Human loiasis in a Cameroonian village: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover clinical trial of a three-day albendazole regimen. Am J Trop Med Hyg 71:211–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamgno J, Boussinesq M. 2002. Effect of a single dose (600 mg) of albendazole on Loa loa microfilaraemia. Parasite 9:59–63. doi: 10.1051/parasite/200209159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boussinesq M. 2012. Loiasis: new epidemiologic insights and proposed treatment strategy. J Travel Med 19:140–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2012.00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klion AD, Horton J, Nutman TB. 1999. Albendazole therapy for loiasis refractory to diethylcarbamazine treatment. Clin Infect Dis 29:680–682. doi: 10.1086/598654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moody AH, Chiodini PL. 2000. Methods for the detection of blood parasites. Clin Lab Haematol 22:189–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2257.2000.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molyneux DH. 2009. Filaria control and elimination: diagnostic, monitoring and surveillance needs. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 103:338–341. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fink DL, Kamgno J, Nutman TB. 2011. Rapid molecular assays for specific detection and quantitation of Loa loa microfilaremia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5:e1299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Ambrosio MV, Bakalar M, Bennuru S, Reber C, Skandarajah A, Nilsson L, Switz N, Kamgno J, Pion S, Boussinesq M, Nutman TB, Fletcher DA. 2015. Point-of-care quantification of blood-borne filarial parasites with a mobile phone microscope. Sci Transl Med 7:286re284. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa3480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boussinesq M. 2006. Loiasis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 100:715–731. doi: 10.1179/136485906X112194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakwe AM, Evehe MS, Titanji VP. 1997. In vitro production and characterization of excretory/secretory products of Onchocerca volvulus. Parasite 4:351–358. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1997044351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinkopff T, Lammie P. 2011. Lack of evidence for the direct activation of endothelial cells by adult female and microfilarial excretory-secretory products. PLoS One 6:e22282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moreno Y, Geary TG. 2008. Stage- and gender-specific proteomic analysis of Brugia malayi excretory-secretory products. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2:e326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennuru S, Semnani R, Meng Z, Ribeiro JM, Veenstra TD, Nutman TB. 2009. Brugia malayi excreted/secreted proteins at the host/parasite interface: stage- and gender-specific proteomic profiling. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 3:e410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biarc J, Simon R, Fonbonne C, Léonard JF, Gautier JC, Pasquier O, Lemoine J, Salvador A. 2015. Absolute quantification of podocalyxin, a potential biomarker of glomerular injury in human urine, by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 1397:81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wood SL, Knowles MA, Thompson D, Selby PJ, Banks RE. 2013. Proteomic studies of urinary biomarkers for prostate, bladder and kidney cancers. Nat Rev Urol 10:206–218. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2013.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desjardins CA, Cerqueira GC, Goldberg JM, Dunning Hotopp JC, Haas BJ, Zucker J, Ribeiro JM, Saif S, Levin JZ, Fan L, Zeng Q, Russ C, Wortman JR, Fink DL, Birren BW, Nutman TB. 2013. Genomics of Loa loa, a Wolbachia-free filarial parasite of humans. Nat Genet 45:495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng.2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burbelo PD, Ramanathan R, Klion AD, Iadarola MJ, Nutman TB. 2008. Rapid, novel, specific, high-throughput assay for diagnosis of Loa loa infection. J Clin Microbiol 46:2298–2304. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00490-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drame PM, Fink DL, Kamgno J, Herrick JA, Nutman TB. 2014. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification for rapid and semiquantitative detection of Loa loa infection. J Clin Microbiol 52:2071–2077. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00525-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fliser D, Novak J, Thongboonkerd V, Argilés A, Jankowski V, Girolami MA, Jankowski J, Mischak H. 2007. Advances in urinary proteome analysis and biomarker discovery. J Am Soc Nephrol 18:1057–1071. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006090956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rifai N, Gillette MA, Carr SA. 2006. Protein biomarker discovery and validation: the long and uncertain path to clinical utility. Nat Biotechnol 24:971–983. doi: 10.1038/nbt1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lutz U, Bittner N, Lutz RW, Lutz WK. 2008. Metabolite profiling in human urine by LC-MS/MS: method optimization and application for glucuronides from dextromethorphan metabolism. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 871:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parker CE, Borchers CH. 2014. Mass spectrometry based biomarker discovery, verification, and validation—quality assurance and control of protein biomarker assays. Mol Oncol 8:840–858. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klion AD, Vijaykumar A, Oei T, Martin B, Nutman TB. 2003. Serum immunoglobulin G4 antibodies to the recombinant antigen, Ll-SXP-1, are highly specific for Loa loa infection. J Infect Dis 187:128–133. doi: 10.1086/345873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dickerson JW, Eberhard ML, Lammie PJ. 1990. A technique for microfilarial detection in preserved blood using Nuclepore filters. J Parasitol 76:829–833. doi: 10.2307/3282801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagaraj N, Mann M. 2011. Quantitative analysis of the intra- and inter-individual variability of the normal urinary proteome. J Proteome Res 10:637–645. doi: 10.1021/pr100835s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suárez-Pantaleón C, Huet AC, Kavanagh O, Lei H, Dervilly-Pinel G, Le Bizec B, Situ C, Delahaut P. 2013. Production of polyclonal antibodies directed to recombinant methionyl bovine somatotropin. Anal Chim Acta 761:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burbelo PD, Goldman R, Mattson TL. 2005. A simplified immunoprecipitation method for quantitatively measuring antibody responses in clinical sera samples by using mammalian-produced Renilla luciferase-antigen fusion proteins. BMC Biotechnol 5:22. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burbelo PD, Ching KH, Klimavicz CM, Iadarola MJ. 2009. Antibody profiling by luciferase immunoprecipitation systems (LIPS). J Vis Exp 32:1459. doi: 10.3791/1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burbelo PD, Lebovitz EE, Notkins AL. 2015. Luciferase immunoprecipitation systems for measuring antibodies in autoimmune and infectious diseases. Transl Res 165:325–335. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henrard DR, Wu S, Phillips J, Wiesner D, Phair J. 1995. Detection of p24 antigen with and without immune complex dissociation for longitudinal monitoring of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Clin Microbiol 33:72–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]