Abstract

The work presented herein addresses a specific portion of the tau pathology, pre-fibrillar oligomers, now thought to be important pathological components in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative tauopathies. In previous work, we generated an antibody against purified recombinant cross-linked tau dimers, called Tau Oligomeric Complex 1 (TOC1). TOC1 recognizes tau oligomers and its immunoreactivity is elevated in Alzheimer’s disease brains. In this report, we expand upon the previous study to show that TOC1 selectively labels tau oligomers over monomers or polymers, and that TOC1 is also reactive in other neurodegenerative tauopathies. Using a series of deletion mutants spanning the tau molecule, we further demonstrate that TOC1 has one continuous epitope located within amino acids 209–224, in the so-called proline rich region. Together with the previous study, our data indicates that TOC1 is a conformation-dependent antibody whose epitope is revealed upon dimerization and oligomerization, but concealed again as polymers form. This characterization of the TOC1 antibody further supports its potential as a powerful biochemical tool that can be used to better investigate the involvement of tau in neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, monoclonal antibodies, oligomers, tau, tauopathy

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia and the sixth leading cause of death in the United States [1]. The prevalence of this disease is ever increasing and death from AD has been rising dramatically. This is in stark contrast to other major diseases such as heart disease and stroke which have been on a steady decline over recent years [1]. These observations highlight the extreme need for better biochemical tools to aid in identifying the cause of AD and other tauopathies and halt progression of these diseases.

AD is characterized pathologically by the presence of extracellular amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and intracellular inclusions composed of the protein tau. While the mechanism by which each protein contributes to the development of AD is still unknown [2], it is apparent that Aβ requires the presence of tau to confer toxicity to the cell [3]. The original amyloid hypothesis proposed that Aβ build-up within the brain was sufficient to cause AD [4]. Indeed, it is clear that there is some distinct connection between Aβ and tau that is unique to AD compared to other dementias [3, 5]. However we now know that tau pathology is more closely correlated with cognitive decline [6] and that mutations in tau alone can cause neurode-generation [7–9]. Additionally, sporadic tauopathies such as corticobasal degeneration (CBD) and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), though not caused by autosomal dominant mutations in the tau gene [10], are nonetheless characterized by tau protein misfolding much the same as that which occurs in AD and familial tauopathies. Moreover, in each of these diseases, the misfolded tau is hyperphosphorylated, although the location and morphology of the tau inclusions vary with the disease state [11].

Hyperphosphorylation has long been implicated in tau pathogenesis in AD and other tauopathies [12–15]. However, there are also reputable studies suggesting that phosphorylation of tau at certain sites may prevent aggregation [16]. The precise role of phosphorylation in changing, maintaining, or codifying tau’s structural conformation may be extremely relevant in determining cellular toxicity [17], as it may be a major determining factor in whether tau stabilizes a toxic oligomeric conformation or attains a less toxic filamentous state through the formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs).

For many years, it was accepted that NFTs were responsible for the tau toxicity associated with AD [6, 18, 19]. However, there are many studies disassociating NFTs from neuronal death [20–23]. It has now been demonstrated that NFTs can exist in the brain for decades without any immediate deleterious effects [24, 25]. Use of the rTg4510 conditional mouse model of tauopathy illustrated that memory impairments and cognitive function deficits could be rescued by tau suppression despite the clear persistence of NFTs [26, 27].

In recent years, tau oligomers have gained considerable attention with respect to their potential toxicity in lieu of NFTs. Animal model studies have shown that pre-fibrillar tau species correlate with synapse loss and behavioral deficits much better than the appearance of NFTs [26, 28]. Cell culture studies with SH-SY5Y cells, incubated with tau monomers, oligomers, and polymers indicate that the oligomers have the most toxic effect [29]. This same group also illustrated how purified recombinant tau oligomers cause greater synaptic and mitochondrial dysfunction than monomers or polymers, and this leads to an increase in memory deficits [30]. A separate study recently demonstrated that only tau oligomers and small fibrils were taken up by neurons in vitro as compared to monomers and long fibrils suggesting conformation is extremely important for trans–synaptic movement of the protein [31].

Thus, the focus of tau research has shifted toward pre-fibrillar aggregates/oligomers in an attempt to elucidate the true neurotoxic species. We successfully generated a monoclonal antibody that selectively recognizes tau dimer/oligomers, termed Tau Oligomeric Complex 1 (TOC1). This antibody was generated using electro-eluted, recombinant, cross-linked tau dimers [32]. Electron microscopy illustrates that these tau dimers associate to form oligomers and short filaments but it is still unclear whether these aggregates can then go on to form longer filaments [32]. Using immunohistochemical studies, we illustrated that TOC1 selectively labels AD pretangles and neuropil threads in situ. By dot blot analysis, we demonstrated that TOC1 reactivity is elevated in AD brains when compared to non-demented controls [32]. TOC1 co-localizes robustly with early markers of tau pathology such as pS422 and shows no co-labeling with late-stage NFT markers such as MN423 [32]. Together this data suggests that TOC1 is useful in identifying aggregates that occur early in the disease.

This current investigation provides an in-depth characterization of the TOC1 antibody highlighting its potential as a tool in understanding AD and other tauopathies. We define the TOC1 epitope, demonstrating that it is formed from a simple continuous region of the tau protein unmasked by a conformational change that occurs upon dimerization, and the availability of this site persists in the oligomer, but is largely remasked in the filamentous polymer [32]. Hence, immunoelectron microscopy indicates that TOC1 is selective for tau oligomers over both monomers and polymers at tau concentrations that fall within the linear region of the ligand binding curve. We further demonstrate that, not only is TOC1 reactive within tissue sections from AD brains, but it also demonstrates robust reactivity within tissue sections from CBD and PSP. This suggests that, although the oligomers may not be identical between diseases, a common mechanism of tau folding and toxicity may exist.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recombinant tau protein expression and purification

The tau protein is numbered according to the longest human isoform found in the central nervous system, hTau40. This isoform consists of 441 amino acids, which includes four microtubule binding repeats (MTBRs) and both alternatively spliced N-terminal exons; a his-tag has been added to the amino terminus to facilitate purification [32]. Full length hTau40 or each of the deletion mutants were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified on a TALON metal affinity resin (Clontech), followed by size exclusion chromatography as previously described [33]. Protein concentration was determined via the BCA assay (Pierce).

Site directed mutagenesis

Full length hTau40 (0–441 aa) containing an N-terminal HIS-tag (~50 ng/μl) was used as the DNA template for all deletion constructs. A two-step protocol was followed. Forward and reverse reactions were set up separately using 10× reaction buffer, forward or reverse primers (see Table 1), dNTPs and PfuTurbo DNA polymerase. Cycling parameters included: 1) 95°C, 30 s; 2) 95°C, 30 s; 3) 45°C, 1 min; 4) 68°C, 8 min. Step 2 is then repeated 3 times followed by a 4°C hold. Equal volumes of the forward and reverse reaction were mixed, 1 μl of PfuTurbo DNA polymerase was added again, and a second thermocycling reaction was performed. Parameters included: 1) 95°C, 30 s; 2) 95°C, 30 s; 3) 50°C, 1 min; 4) 68°C, 8 min. Step 2 cycles 17 times; 5) 68°C, 7 min. To ensure correct sizing and efficient amplification, samples were separated on a 1% agarose gel. Dpn1 (10 U/μl) was then added to the remainder of the sample at 37°C for 4 h in order to digest the parental strand. Each construct was transformed into DH5α cells, purified by miniprep (Qiagen) and verified by DNA sequence analysis.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for generating each deletion or mutation construct

| Primer | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Δ209–228 | GGCTCCCCAGGCACTCCCGGCAGCG TCCGTACTCCACCCAAGTCGCCG |

CGGCGACTTGGGTGGAGTACGGACGCTGCCG GGAGTGCCTGGGGAGCC |

| Δ221–227 | CCCCGTCCCTTCCAACCCCACCCACC | GACTTGGGTGGAGTACGGACCACGG |

| Δ221–238 | CGCACCCCGTCCCTTCCAACCCCACCCACCGCCAA GAGCCGCCTGCAGACAGCCCCCG |

CGGGGGCTGTCTGCAGGCGGCTCTTGGCGG TGGGTGGGGTTGGAAGGGACGGGGTGCG |

| Δ360–369 | GATTGGGTCCCTGGACAATAAGATTGAAACCC ACAAG |

CTTGTGGGTTTCAATCTTATTGTCCAGGGAC CCAAT |

| Δ370–380 | CGTCCCTGGCGGAGGAAATAAAAACGCCAAAGCC | GGCTTTGGCGTTTTTATTTCCTCCGCCAG GGACG |

| Δ380–390 | CAAGCTGACCTTCCGCGAGATCGTGTACAAGT | ACTTGTACACGATCTCGCGGAAGGTCAGCTTG |

| Δ391–397 | GACCACGGGGCGGTGGTGTCTGGG | CCCAGACACCACCGCCCCGTGGTC |

| Δ400–410 | GTCGCCAGTGGTGGTCTCCTCCACCG | CGGTGGAGGAGACCACCACTGGCGAC |

| Δ411–421 | TCCACGGCATCTCAGCAATTCGCCCCAGC | GCTGGGGCGAATTGCTGAGATGCCGTGGA |

| K225G | CCCACCCACCCGGGAGCCCAAGGGC | GGGTGGAGTACGGACCACTGCCACG |

| R221G/E222G/P223G | GTC CCT TCC AAC CCC ACC CAC CGG CGG CGG CAA GAA GGT GGC AGT GGT CCG |

CGG ACC ACT GCC ACC TTC TTG CCG CCG CCG GTG GGT GGG GTT GGA AGG GA |

In vitro aggregation

Aggregation of all tau proteins (4 μM) was induced with 75 μM arachidonic acid (AA) at room temperature until equilibrium was obtained (~6 h). Assays were performed in a reaction mixture containing 10 mM Na-HEPES pH7.6, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, and 0.1 mM Na-EGTA. Working solutions of AA were prepared in 100% ethanol immediately prior to use. Efficiency of aggregation was assayed using right angle Laser Light Scattering and confirmed by electron microscopy [34].

Electron microscopy/immunogold labeling of recombinant tau aggregates

For negatively-stained electron microscopy (EM), aggregated tau was fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and spotted onto 300-mesh formvar/carbon coated copper grids (Electron Microscopy Services). Each grid was rinsed with filtered H2O and stained with 2% uranyl acetate. Conversely, in the case of negatively-stained TOC1 immunogold, samples were not fixed, as this negatively impacts the TOC1 epitope. Nickel grids were used for immunogold labeling and samples were blocked in 0.2% gelatin, 5% goat serum in 1× TBS. Grids were rinsed in 1× TBS before incubation with TOC1 primary antibody at 1:2,500 for 1 h at room temperature (RT). Following rinsing with 1× TBS, 6 nm diameter gold-conjugated anti-mouse IgM (μ-chain specific) (Sigma) secondary antibody (1:50) was applied to the samples and allowed to incubate for 1 h at RT. Grids were rinsed in 10× TBS to reduce nonspecific labeling, followed by H2O, prior to negative contrast with 2% uranyl acetate. Images were captured using the FEI Tecnai Spirit G2 transmission electron microscope at the Northwestern University Cell Imaging Facility.

Immunoblot and dot blot analysis

Each of the deletion mutants were diluted to 10 ng/μl in 1 × PBS. 1 μl of each mutant sample was spotted directly onto nitrocellulose membranes. 10 μg of hTau40 from three different protein purifications were separated on a 10% Tris-Glycine gel by SDS-PAGE. Both western and dot blot membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-Tween (0.5%) pH 7.4, followed by incubation in primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Antibodies were used at the following dilutions: TOC1 1:10,000, Tau12 1:1,000,000, Tau5 1:50,000. Membranes were rinsed in TBS-Tween-20 and incubated in peroxidase conjugated horse anti-mouse secondary antibody IgG (H + L) (Vector) 1:5000 for 1 h at RT. Signal detection was performed using an enhanced chemiluminescent (ECL) system (Pierce) and developed on X-ray film. Quantification of dot blots was accomplished using ImageJ software (National Institute of Health).

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue sections of severe AD, CBD, and PSP cases from the entorhinal cortex (40 μm) were obtained from the Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease Center at Northwestern University (CNADC). All sections were subjected to antigen retrieval with sodium citrate pH 6.1. Hematoxylin counter-staining was performed to identify nuclei. TOC1 was used at 1:5,000 and allowed to incubate with the tissue overnight at 4°C.The tissue was incubated in biotinylated goat-anti-mouse IgM (1:500) for 2 h at RT followed by immersion in ABC solution for 1 h at RT. Staining was developed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma). Sections were mounted onto glass slides, dehydrated through graded alcohols and cover-slipped with Permount.

RESULTS

The TOC1 epitope is formed from a single continuous region on the tau protein

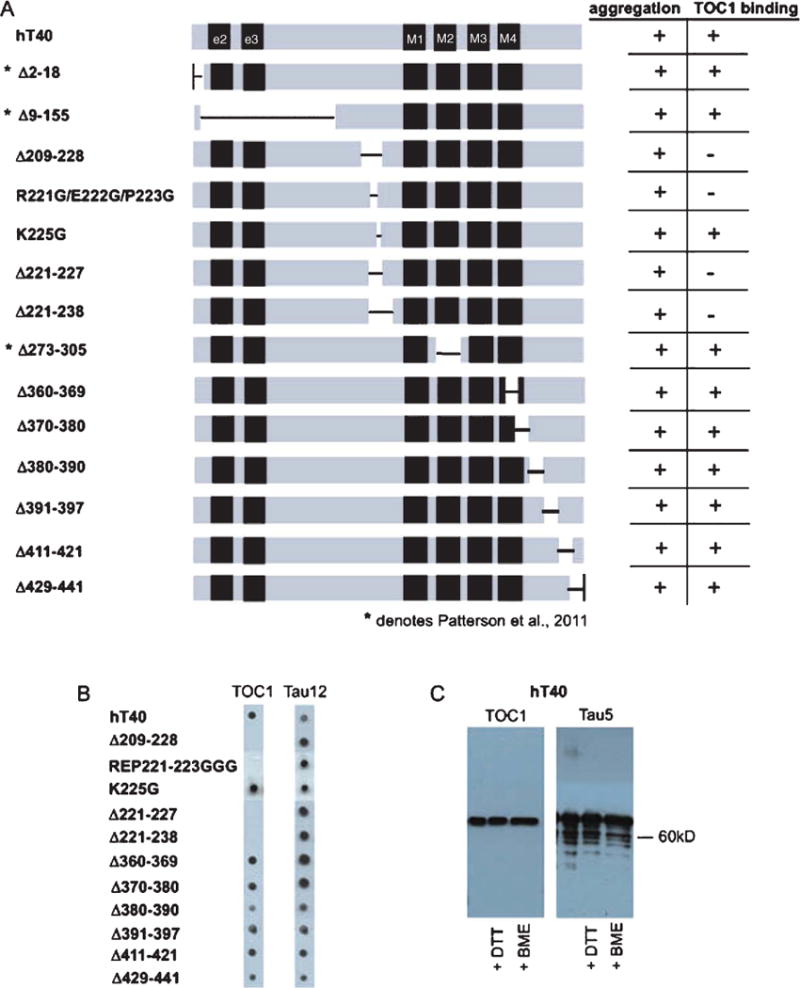

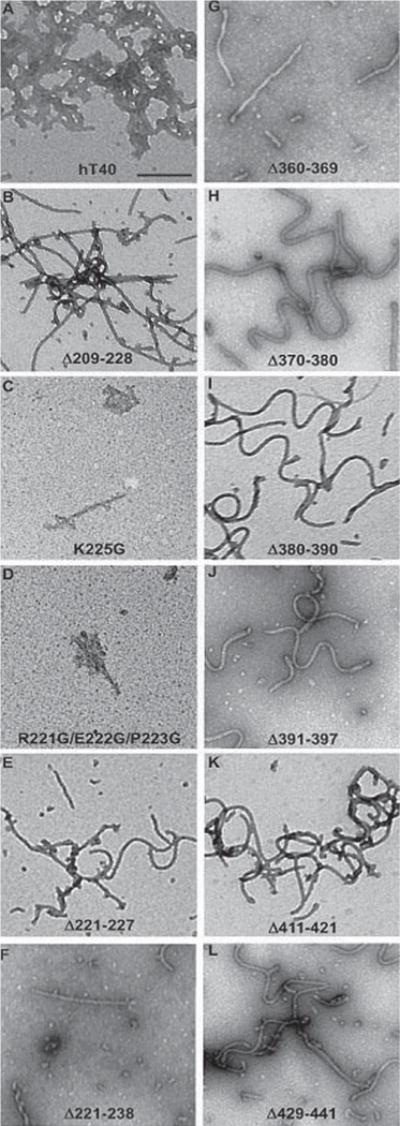

Previous work using the longest tau isoform (441 aa) demonstrated that the TOC1 epitope was located primarily within the aa region 155–244 and suggested the potential for a second less robust site within the C-terminal domain, aa 376–441 [32]. This preliminary investigation used deletion mutants with long portions of the protein deleted necessitating more focused site-directed mutagenesis to further fine-tune the epitope. We also generated multiple new deletion mutants located within the C-terminal domain that were much smaller than those used in previous analyses (10–20 aa) thereby allowing us to more accurately assess whether a discontinuous portion of this epitope existed (Fig. 2A). Following expression and purification of each of the mutant protein constructs, aggregation was performed under our standard conditions and aggregate formation confirmed by electron microscopy (Fig. 1). The protein was then diluted to 10 ng/μl for dot blot analysis. All deletion mutants within the C-terminal domain were TOC1 positive. Aggregates of four mutants located around the central portion of the protein within the proline-rich region showed no reactivity with TOC1. These include Δ209–228, Δ221–227, and Δ221–238 and the triple point mutation R221G/E222G/P223G (Fig. 2A, B). However, the point mutation K225G does not affect the TOC1 signal, indicating that aa 225 is not within the TOC1 epitope, defining the TOC1 epitope within aa 209–224 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

TOC1 has a continuous epitope between amino acids 209–224. A) Schematic of tau protein representing the location of mutations and deletions for each construct. All mutant proteins aggregated, but only a subset bind TOC1. * indicates constructs that were analyzed in Patterson et al. [32]. B) Dot blots on aggregated tau constructs reveal TOC1 does not detect the deletion mutant lacking amino acids 209–224. C) Western blot on denatured tau in non-reducing or two different reducing conditions (DTT, BME) indicates the ability of TOC1 to bind to all forms of denatured tau.

Fig. 1.

Tau deletions do not affect the protein’s ability to aggregate. A–L) Negatively stained EM images of hTau40 (A) and mutant constructs Δ209–228 (B), K225G (C), R221G/E222G/P223G (D), Δ221–227 (E), Δ221–238 (F), Δ360–369 (G), Δ370–380 (H), Δ380–390 (I), Δ391–397 (J), Δ411–421 (K), Δ429–441 (L). None of the mutations or deletions listed affected the ability of the protein to aggregate. Scale bar = 200 nm.

We were also successful in blotting hTau40 with TOC1 after separation by SDS-PAGE under both reducing (DTT or BME) and non-reducing conditions (Fig. 2C). This is in contrast to our previous report regarding our inability to observe reactivity to TOC1 on western blots. Although there are antibodies with a discontinuous epitope that can be detected by western blot such as Alz50 [35], more often, this result is highly suggestive of a linear continuous epitope, in agreement with the more complete epitope mapping presented herein.

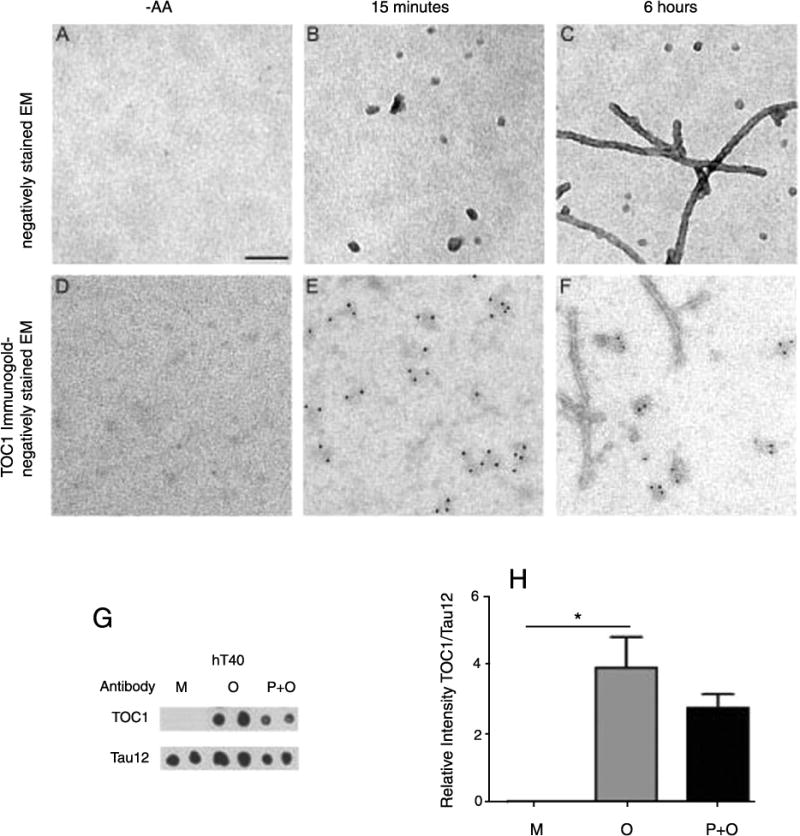

TOC1 selectively labels tau oligomers over monomers and polymers

hTau40 was aggregated for 15 min or 6 h under our normal aggregation conditions as outlined in the Materials and Methods. This results in the generation of tau oligomers and polymers, respectively, although the polymer preparation also contains a significant number of oligomers. Monomers were prepared without AA and all tau species were utilized to assess TOC1 labeling with colloidal gold. TOC1 selectively labels tau oligomers (Fig. 3E) with no visible labeling of tau monomers (Fig. 3D) and very limited labeling of polymers (Fig. 3F). Dot blot analysis confirms that TOC1 does not detect recombinant tau monomers (M) (Fig. 3G) and quantification by densitometry demonstrates that TOC1 has the highest selectivity for recombinant oligomers (O) (Fig. 3H).

Fig. 3.

TOC1 preferentially detects tau oligomers. A–C) Negatively stained EM images of tau in the absence of arachidonic acid (−AA) or in its presence after 15 minutes or 6 hours of aggregation. D–F) TOC1 immunogold labeling with negatively stained EM demonstrates that TOC1 preferentially detects tau oligomers. G–H) Dot blot (G) and densitometry (H) of hT40 monomers (M), oligomers (O) and polymers + oligomers (P + O). Oligomers (O) and polymers+oligomers (P + O) were formed by incubation with arachidonic acid (AA) for 15 minutes (O) or 6 hours (P + O); monomers (M) were not incubated with AA. Scale bar = 100 nm.

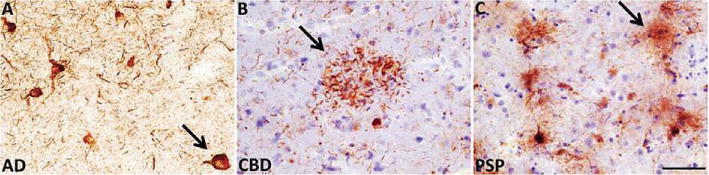

TOC1 is reactive in other tauopathies in addition to AD

Tau is an extremely flexible protein; within AD we observe at least three different conformations. Tau monomers, tau oligomers, and tau filaments likely each necessitate the assumption of certain unique conformational elements. Since our antibody, TOC1, is selective for tau oligomers, it was used to investigate whether tau oligomers are present in other tauopathies such as PSP and CBD. Immunohistochemistry of human brain tissue demonstrates that each of the aforementioned diseases show robust labeling with TOC1 (Fig. 4). Although it seems rational to speculate that the oligomers may be slightly different between these diseases, this result implicates a structural motif (perhaps a dimer) common to all tauopathies (See Discussion).

Fig. 4.

TOC1 reacts with brain pathology in three different tauopathies. A–C) TOC1 immunohistochemistry on entorhinal cortex sections from (A) human Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and frontal cortex sections of (B) corticobasal degeneration (CBD) and (C) progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) brains. Arrows in each panel indicate: (A) pretangle neuron, (B) astrocytic plaque (“crown of thorns”), and (C) tufted astrocyte. Scale bar = 50 μm

DISCUSSION

AD and other tauopathies are a huge socioeconomic problem in today’s world. Given the fact that there are presently only a few suggested disease-modifying therapies such as inhibition of tau hyperphosphorylation [36], activation of proteolytic or other degradation pathways [37], microtubule stabilization [38, 39], small molecule inhibitors of aggregation [40–42], and immunotherapy [43–45], the need for a better understanding of tau-related disease mechanisms is clear. The tau protein has been implicated in AD for many years but the exact mechanism by which tau aggregates exert their toxic effects on neurons remains unresolved. More recently, models of Aβ toxicity in culture [46] and in transgenic mice [3] were shown to depend on the presence of tau; if the tau gene was absent, Aβ was not toxic to cultured neurons and amyloid-β protein precursor transgenic mice did not display behavioral deficits.

The structure of tau is poorly understood. This is because it is a highly flexible molecule that can rapidly change shape due to the number of Pro-Gly motifs in its sequence. For years, tau was thought to be a “natively unfolded protein” [47, 48] in its monomeric state. The first hint of a defined structure was provided by mapping of the discontinuous Alz50 epitope [35, 49], indicating that prior to or during aggregation, the amino terminal region of tau folds upon a domain in the MTBR forming a hairpin shape to create this site. Subsequently, FRET studies indicated that the tau monomer forms a “paperclip” conformation in which the C-terminus folds over onto the MTBR and the N-terminus then folds back onto the C-terminus [50]. This supports previous work from our lab indicating that the C-terminus of tau can interact with the MTBR and inhibit tau aggregation [51].

In recent years, the focus of which particular tau aggregate is responsible for tau toxicity has shifted from filaments or NFTs to pre-fibrillar aggregates known as oligomers [20, 21, 26, 28, 32]. A large study on cholinergic basal forebrain neurons in the nucleus basalis demonstrated that pretangle neurons and neuropil thread staining with the early tau marker pS422 correlates extremely well with cognitive decline prior to the emergence of significant NFT pathology [52]. Additionally, synaptic loss correlates better with cognitive decline than NFTs, which again suggests that tau toxicity is associated with tau aggregates that formed before the generation of NFTs [53]. Finally, we used isolated squid axoplasm to demonstrate that wild-type tau aggregates inhibit FAT in the anterograde direction only [54]. Subsequently, we showed that the molecular chaperone Hsp70 prevents inhibition of FAT by selectively binding to tau oligomers [55]. These and the data cited from other laboratories all suggest that tau oligomers constitute the toxic form of tau as opposed to polymers and NFTs [26, 28, 52, 53].

Our characterization of the “Tau Oligomeric Complex 1” (TOC1) antibody indicate that it is of the IgM (kappa) subclass and that in tissue it reacts with pretangle neurons, neuropil threads, and dystrophic neurites in vulnerable neurons from Braak stages I–VI [32]. Interestingly, it does not react with NFTs. TOC1-positive tau aggregates form upon exposure to AA in our standard in vitro tau assembly assay; however, oligomers appear to form prior to filaments within the first 15 minutes after AA addition. After 6 h of incubation, the aggregate mixture consists of both oligomers and filaments, although TOC1 reacts predominantly with the oligomers, only showing occasional end-labeling of in vitro formed filaments.

Epitope mapping utilizing site-directed mutagenesis to form internal deletion/religation constructs, indicates that the TOC1 epitope resides within the region delimited by aa 209–224. This demonstrates that the binding site is located within the proline-rich region just adjacent to the MTBRs. Deletion mutants located within the C-terminus all show robust TOC1 binding, which illustrates that there is no secondary epitope site within the C-terminal domain as initial data had suggested [32]. However, conformational change is involved in exposing the epitope for binding. When we compared aggregated hTau40 oligomers and polymers with tau monomers, we observed preferential binding to tau oligomers over monomers or filaments. Even after 6 h of aggregation, a substantial number of oligomers are still present in the assembly mixture indicating the need for future experiments in which purified oligomers and filaments will be produced for use in quantitative ligand binding experiments with TOC1.

Subsequent to defining the epitope, we performed some western blotting studies with aggregated recombinant hTau40. Since preparing samples for western blot involves denaturation, this analysis informs us that TOC1 binds to all forms of denatured tau, whereas the epitope is somehow masked in its native monomeric state, preventing antibody binding. It is quite apparent that TOC1 preferentially reacts with tau in its oligomeric versus its filamentous or monomeric states when binding is assayed using immunogold labeling—oligomers are consistently labeled while monomers are not labeled at all. The occasional end-labeling of polymers described above, perhaps suggests a stacking mechanism of the oligomers to allow incorporation into filaments. However, this is speculation at best, since it is not known whether oligomers extend into filaments or whether oligomers and filaments represent end products of separate pathways. Tissue sections of other tauopathies stained with TOC1 showed robust labeling in all diseases tested. This indicates that the TOC1 antibody may prove a powerful tool for tauopathy characterization. Although largely labeling neuropil threads and pretangle neurons in AD, TOC1 reactivity demonstrates the characteristic astrocytic plaques or “crown of thorns” morphology in CBD; similarly PSP tissue reactivity indicated the presence of tufted astrocytes, the pathognomonic structures characteristic of this disease [10]. Since TOC1 is reactive in multiple tauopathies, its reactivity must depend on the appearance of a conformation common to the three diseases assayed. Although this could be an oligomeric structure, the one structure that would most likely be common to any disease dependent on tau aggregation is the dimer. It is instructive to note that other conformational tau antibodies such as Alz50 are also reactive in AD, PSP, and CBD (unpublished observations). Comparison of TOC1 and Alz50 reactivity in early AD, PSP, and CBD may well enlighten us as to the structural changes possible in tau common to different disease-specific forms of pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

Imaging work was performed at the Northwestern University Cell Imaging Facility generously supported by NCI CCSG P30 CA060553 awarded to the Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center. This work was supported by the National Institute of Health grant AG014449 (to LIB) and the Department of Defense (Henry Jackson) Grant HT 9404-12-1-0002. DSH was supported in part by NIA training grant T32 AG20506. This study was also supported in part by an Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center grant (P30 AG013854) from the National Institute on Aging to Northwestern University, Chicago Illinois. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the Neuropathology Core.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://www.j-alz.com/disclosures/view.php?id=1900).

References

- 1.Thies W, Bleiler L. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:208–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang HC, Jiang ZF. Accumulated amyloid-beta peptide and hyperphosphorylated tau protein: Relationship and links in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16:15–27. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberson ED, Scearce-Levie K, Palop JJ, Yan F, Cheng IH, Wu T, Gerstein H, Yu GQ, Mucke L. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid beta-induced deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Science. 2007;316:750–754. doi: 10.1126/science.1141736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: Progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ittner LM, Gotz J. Amyloid-beta and tau–a toxic pas de deux in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:65–72. doi: 10.1038/nrn2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, Baker M, Froelich S, Houlden H, Pickering-Brown S, Chakraverty S, Isaacs A, Grover A, Hackett J, Adamson J, Lincoln S, Dickson D, Davies P, Petersen RC, Stevens M, de Graaff E, Wauters E, van Baren J, Hillebrand M, Joosse M, Kwon JM, Nowotny P, Heutink P, et al. Association of missense and 5′-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature. 1998;393:702–705. doi: 10.1038/31508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poorkaj P, Bird TD, Wijsman E, Nemens E, Garruto RM, Anderson L, Andreadis A, Wiederholt WC, Raskind M, Schellenberg GD. Tau is a candidate gene for chromosome 17 frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:815–825. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spillantini MG, Murrell JR, Goedert M, Farlow MR, Klug A, Ghetti B. Mutation in the tau gene in familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7737–7741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickson DW. Neuropathologic differentiation of progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration. J Neurol. 1999;246(Suppl 2):II6–I15. doi: 10.1007/BF03161076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spillantini MG, Bird TD, Ghetti B. Frontotemporal dementia and Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17: A new group of tauopathies. Brain Pathol. 1998;8:387–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00162.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avila J. Tau aggregation into fibrillar polymers: Taupathies. FEBS Lett. 2000;476:89–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01676-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bancher C, Brunner C, Lassmann H, Budka H, Jellinger K, Wiche G, Seitelberger F, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Wisniewski HM. Accumulation of abnormally phosphorylated tau precedes the formation of neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 1989;477:90–99. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91396-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Schroter C, Lichtenberg-Kraag B, Steiner B, Berling B, Meyer H, Mercken M, Vandermeeren A, Goedert M, et al. The switch of tau protein to an Alzheimer-like state includes the phosphorylation of two serine-proline motifs upstream of the microtubule binding region. EMBO J. 1992;11:1593–1597. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05204.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bondareff W, Harrington CR, Wischik CM, Hauser DL, Roth M. Absence of abnormal hyperphosphorylation of tau in intracellular tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1995;54:657–663. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199509000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider A, Biernat J, von Bergen M, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM. Phosphorylation that detaches tau protein from microtubules (Ser262, Ser214) also protects it against aggregation into Alzheimer paired helical filaments. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3549–3558. doi: 10.1021/bi981874p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Sierra F, Ghoshal N, Quinn B, Berry RW, Binder LI. Conformational changes and truncation of tau protein during tangle evolution in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2003;5:65–77. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Hyman BT. Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1992;42:631–639. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez-Isla T, Hollister R, West H, Mui S, Growdon JH, Petersen RC, Parisi JE, Hyman BT. Neuronal loss correlates with but exceeds neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:17–24. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maeda S, Sahara N, Saito Y, Murayama M, Yoshiike Y, Kim H, Miyasaka T, Murayama S, Ikai A, Takashima A. Granular tau oligomers as intermediates of tau filaments. Biochemistry. 2007;46:3856–3861. doi: 10.1021/bi061359o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maeda S, Sahara N, Saito Y, Murayama S, Ikai A, Takashima A. Increased levels of granular tau oligomers: An early sign of brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Res. 2006;54:197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spires TL, Orne JD, SantaCruz K, Pitstick R, Carlson GA, Ashe KH, Hyman BT. Region-specific dissociation of neuronal loss and neurofibrillary pathology in a mouse model of tauopathy. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1598–1607. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramsden M, Kotilinek L, Forster C, Paulson J, McGowan E, SantaCruz K, Guimaraes A, Yue M, Lewis J, Carlson G, Hutton M, Ashe KH. Age-dependent neurofibrillary tangle formation, neuron loss, and memory impairment in a mouse model of human tauopathy (P301L) J Neurosci. 2005;25:10637–10647. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3279-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guillozet-Bongaarts AL, Cahill ME, Cryns VL, Reynolds MR, Berry RW, Binder LI. Pseudophosphorylation of tau at serine422 inhibits caspase cleavage: In vitro evidence and implications for tangle formation in vivo. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1005–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morsch R, Simon W, Coleman PD. Neurons may live for decades with neurofibrillary tangles. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:188–197. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199902000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santacruz K, Lewis J, Spires T, Paulson J, Kotilinek L, Ingelsson M, Guimaraes A, DeTure M, Ramsden M, McGowan E, Forster C, Yue M, Orne J, Janus C, Mariash A, Kuskowski M, Hyman B, Hutton M, Ashe KH. Tau suppression in a neurodegenerative mouse model improves memory function. Science. 2005;309:476–481. doi: 10.1126/science.1113694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Corre S, Klafki HW, Plesnila N, Hubinger G, Obermeier A, Sahagun H, Monse B, Seneci P, Lewis J, Eriksen J, Zehr C, Yue M, McGowan E, Dickson DW, Hutton M, Roder HM. An inhibitor of tau hyperphosphorylation prevents severe motor impairments in tau transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9673–9678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602913103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berger Z, Roder H, Hanna A, Carlson A, Rangachari V, Yue M, Wszolek Z, Ashe K, Knight J, Dickson D, Andorfer C, Rosenberry TL, Lewis J, Hutton M, Janus C. Accumulation of pathological tau species and memory loss in a conditional model of tauopathy. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3650–3662. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0587-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lasagna-Reeves CA, Castillo-Carranza DL, Guerrero-Muoz MJ, Jackson GR, Kayed R. Preparation and characterization of neurotoxic tau oligomers. Biochemistry. 2010;49:10039–10041. doi: 10.1021/bi1016233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lasagna-Reeves CA, Castillo-Carranza DL, Sengupta U, Clos AL, Jackson GR, Kayed R. Tau oligomers impair memory and induce synaptic and mitochondrial dysfunction in wild-type mice. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6:39. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu JW, Herman M, Liu L, Simoes S, Acker CM, Figueroa H, Steinberg JI, Margittai M, Kayed R, Zurzolo C, Di Paolo G, Duff KE. Small misfolded Tau species are internalized via bulk endocytosis and anterogradely and retrogradely transported in neurons. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:1856–1870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.394528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patterson KR, Remmers C, Fu Y, Brooker S, Kanaan NM, Vana L, Ward S, Reyes JF, Philibert K, Glucksman MJ, Binder LI. Characterization of prefibrillar tau oligomers in vitro and in Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:23063–23076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.237974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carmel G, Leichus B, Cheng X, Patterson SD, Mirza U, Chait BT, Kuret J. Expression, purification, crystallization, and preliminary X-ray analysis of casein kinase-1 from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7304–7309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gamblin TC, King ME, Dawson H, Vitek MP, Kuret J, Berry RW, Binder LI. In vitro polymerization of tau protein monitored by laser light scattering: Method and application to the study of FTDP-17 mutants. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6136–6144. doi: 10.1021/bi000201f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carmel G, Mager EM, Binder LI, Kuret J. The structural basis of monoclonal antibody Alz50’s selectivity for Alzheimer’s disease pathology. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32789–32795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gong CX, Iqbal K. Hyperphosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein tau: A promising therapeutic target for Alzheimer disease. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:2321–2328. doi: 10.2174/092986708785909111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson GV, Jope RS, Binder LI. Proteolysis of tau by calpain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;163:1505–1511. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trojanowski JQ, Smith AB, Huryn D, Lee VM. Microtubule-stabilising drugs for therapy of Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders with axonal transport impairments. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2005;6:683–686. doi: 10.1517/14656566.6.5.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang B, Maiti A, Shively S, Lakhani F, McDonald-Jones G, Bruce J, Lee EB, Xie SX, Joyce S, Li C, Toleikis PM, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Microtubule-binding drugs offset tau sequestration by stabilizing microtubules and reversing fast axonal transport deficits in a tauopathy model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:227–231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406361102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pickhardt M, Gazova Z, von Bergen M, Khlistunova I, Wang Y, Hascher A, Mandelkow EM, Biernat J, Mandelkow E. Anthraquinones inhibit tau aggregation and dissolve Alzheimer’s paired helical filaments in vitro and in cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3628–3635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410984200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pickhardt M, Larbig G, Khlistunova I, Coksezen A, Meyer B, Mandelkow EM, Schmidt B, Mandelkow E. Phenylthiazolyl-hydrazide and its derivatives are potent inhibitors of tau aggregation and toxicity in vitro and in cells. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10016–10023. doi: 10.1021/bi700878g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bulic B, Pickhardt M, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. Tau protein and tau aggregation inhibitors. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59:276–289. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asuni AA, Boutajangout A, Quartermain D, Sigurdsson EM. Immunotherapy targeting pathological tau conformers in a tangle mouse model reduces brain pathology with associated functional improvements. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9115–9129. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2361-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boutajangout A, Ingadottir J, Davies P, Sigurdsson EM. Passive immunization targeting pathological phospho-tau protein in a mouse model reduces functional decline and clears tau aggregates from the brain. J Neurochem. 2011;118:658–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boutajangout A, Quartermain D, Sigurdsson EM. Immunotherapy targeting pathological tau prevents cognitive decline in a new tangle mouse model. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16559–16566. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4363-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rapoport M, Dawson HN, Binder LI, Vitek MP, Ferreira A. Tau is essential to beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6364–6369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092136199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mandelkow EM, Schweers O, Drewes G, Biernat J, Gustke N, Trinczek B, Mandelkow E. Structure, microtubule interactions, and phosphorylation of tau protein. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;777:96–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb34407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schweers O, Schonbrunn-Hanebeck E, Marx A, Mandelkow E. Structural studies of tau protein and Alzheimer paired helical filaments show no evidence for beta-structure. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24290–24297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jicha GA, Bowser R, Kazam IG, Davies P. Alz-50 and MC-1, a new monoclonal antibody raised to paired helical filaments, recognize conformational epitopes on recombinant tau. J Neurosci Res. 1997;48:128–132. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19970415)48:2<128::aid-jnr5>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jeganathan S, von Bergen M, Brutlach H, Steinhoff HJ, Mandelkow E. Global hairpin folding of tau in solution. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2283–2293. doi: 10.1021/bi0521543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berry RW, Abraha A, Lagalwar S, LaPointe N, Gamblin TC, Cryns VL, Binder LI. Inhibition of tau polymerization by its carboxy-terminal caspase cleavage fragment. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8325–8331. doi: 10.1021/bi027348m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vana L, Kanaan NM, Ugwu IC, Wuu J, Mufson EJ, Binder LI. Progression of tau pathology in cholinergic basal fore-brain neurons in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2533–2550. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crews L, Masliah E. Molecular mechanisms of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:R12–R20. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kanaan NM, Morfini GA, Lapointe NE, Pigino GF, Patterson KR, Song Y, Andreadis A, Fu Y, Brady ST, Binder LI. Pathogenic forms of tau inhibit kinesin-dependent axonal transport through a mechanism involving activation of axonal phosphotransferases. J Neurosci. 2011;31:9858–9868. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0560-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Patterson KR, Ward SM, Combs B, Voss K, Kanaan NM, Morfini G, Brady ST, Gamblin TC, Binder LI. Heat shock protein 70 prevents both tau aggregation and the inhibitory effects of preexisting tau aggregates on fast axonal transport. Biochemistry. 2011;50:10300–10310. doi: 10.1021/bi2009147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]