SECTION 3

Management of Anemia in diabetic kidney disease

The rising prevalence and impact of diabetes and its complications, including anemia, which put patients at high risk of mortality, clearly mandates the need for early identification and institution of therapy in DKD patients.[46] Especially, targeting anemia, which is common to both CKD and diabetes,[85] can be an important therapeutic strategy to optimize outcomes in these patients. This could follow an initial clinical assessment of anemia by distinct laboratory investigations, including a complete blood count, absolute reticulocyte count, serum ferritin to assess iron stores, serum TSAT or content of Hb in reticulocytes to assess adequacy of iron for erythropoiesis.[109] Yet, the decision to initiate treatment is generally based on the potential benefits (improvements in QOL and symptoms and avoidance of the need for blood transfusions) and risks in individual cases.[72] In general, while treatment of anemia using ESAs is well-accepted in patients on dialysis, emerging evidence suggests that earlier initiation of anemia treatment in CKD may delay the onset of ESKD and decrease mortality.[42,46] Even so, anemia is frequently under-recognized and undertreated during the predialysis stage of kidney disease, a period when anemia correction may have the greatest impact on disease outcome. It is often seen that few patients receive ESAs in the predialysis period and Hb concentrations are often <9 g/dl at the start of hemodialysis.[110] This lagging strategy becomes more important when considering the fact that the size of anemic patient population is much larger in the nondialysis dependent population than the hemodialysis population.[111]

Apart from vitamin B12 and folate deficiency, lowered EPO and iron are prime factors underlying anemia of CKD. Therefore, the treatment ought to be focused on timely initiation, response and maintenance of levels of EPO and serum iron in the body. Accordingly, ESAs and iron remain the two mainstays of treatment for patients with anemia associated with CKD.[72] Finally, regularly monitoring of CV status of the patient should be done to identify the risk of future adverse CV events.

Need for individualization of therapy

Timely start of ESA therapy, iron supplementation and ’active’ monitoring of patients may allow achievement of Hb target levels and permit a greater steadiness of these levels during the maintenance phase of ESA therapy.[111] However, the treatment needs to be individualized dependent on the patient's clinical status, together considering numerous variables affecting the complex management, and mostly due to the possible narrow therapeutic window, i.e. unclear optimal level of Hb for greatest clinical benefit.[46,96] Furthermore, although, all ESAs effectively increase Hb levels, differences concerning route of administration, pharmacokinetics, and dosing frequency and efficiency should be considered to maximize the treatment benefits for the individual patient.

Hemoglobin target

The optimal Hb target in patients with CKD anemia is a matter of debate. However, based on overall available evidences, Hb level of 10−12 g/dl seems adequate for most patients of CKD anemia.[100,106,112] The rationale is further supported by observation that maintaining this close range of Hb levels in CKD patients is associated with maximum improvements in QOL, reduced morbidity, and improved cardiac health and survival.[51,113] The target Hb can be tailored for each patient taking into consideration the age, physical activity, comorbidity, and response to treatment.[100] However, rapid increases in Hb level should always be avoided, and lowest appropriate ESA doses should be used while trying to achieve treatment target of 10−12 g/dl in most patients.[114] It is critical to maintain Hb levels between 10 g/dL and 12 g/dL in all adults with DKD because higher Hb levels may be associated with increased mortality. Particularly, targeting Hb >13 g/dl is harmful and may increase risk of hypertension and vascular thrombosis.[74,85,115] The strategy may require changes to the ESA dose, dosing frequency, and iron supplementation over the course of treatment and considering proactive management of conditions affecting ESA responsiveness.[116]

Variables affecting the risk and management

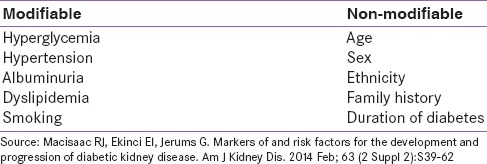

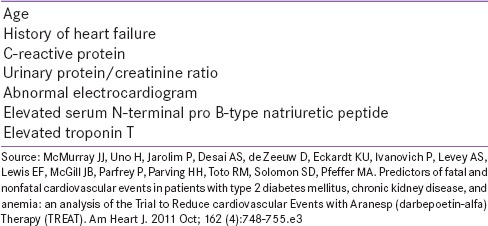

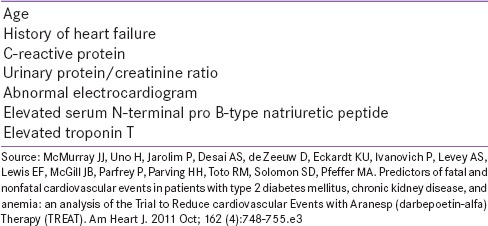

In DKD, anemia acts as independent risk factor associated with the loss of kidney function, and defines a group of patients at high risk for death and CV complications, thus making early identification and intervention important.[58,72,96] Nonetheless, screening and subsequent management may be influenced by certain variables, such as age and comorbidity, that differ among patients. Furthermore, numerous factors have been identified as predictors of CV risk in these patients, which may be useful in risk stratification in clinical practice, and tailor treatment accordingly [Table 7].[117] For instance, anemia is associated with a rapid decline in kidney function in patients with coexisting CKD and heart failure.[97] These variables have implications that encompass management as well.

Table 7.

Factors strongly predicting the cardiovascular risk in diabetic kidney disease patients with anemia

Iron therapy in diabetic kidney disease

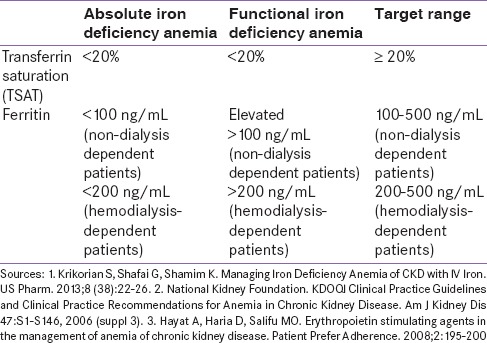

Due to reduced EPO secretion in the body, CKD patients with iron deficiency most often need ESA therapy coupled with parenteral iron therapy since constant iron availability is required for effective erythropoiesis when the process is stimulated using ESAs.[118] This is because once ESAs are commenced, a rapid depletion of iron stores occurs because of erythropoiesis, and failure to correct iron deficiency will lead to EPO resistance.[74] As an adjunct to ESA therapy, iron can therefore effectively relieve iron-restricted erythropoiesis, improve ESA response, help to maintain the target Hb levels, reduce ESA dosing requirements, and consequently balance the risks of therapy.[50]

The supplementation of iron should essentially begin prior to initiate the ESA therapy in order to maintain adequate ESA response.[119] Broadly, an increase in Hb >1 g/dL over 1 month would indicate a therapeutic response to iron therapy, but monitoring is important to avoid iron overload or toxicity. Care should be taken to prevent the serum ferritin rising >800–1000 m/l and the TSAT >50%.[120]

Oral versus intravenous iron preparations

Iron can be replenished through oral or intravenous (IV) route,[121] with their limitations and benefits to affect use in patients’ subgroups. For instance, oral agents do not ensure complete bioavailability of iron, nor are they able to replenish body iron stores adequately. Moreover, drug interactions and occurrence of common gastrointestinal side effects could further hamper patient compliance with oral iron therapy.[85,118] This applies differently to IV forms where multiple doses and visits may be a limitation for compliance.

In addition, the choice among oral versus IV iron preparations would depend on clinical profile of the patient, besides convenience and compliance. While nondialysis dependent patients can receive iron orally or IV, based on their clinical status and convenience, IV iron is preferred for the hemodialysis-dependent patients,[109] who often exhibit limited absorption of oral iron. IV iron therapy may result in more rapid increase in both Hb and ferritin in CKD patients; in contrast, oral iron may increase Hb without increases in iron stores.[122]

Safety concerns with different intravenous iron preparations

There are concerns regarding the safety of IV iron supplementation due to increased risk of serious adverse events especially among nondialyzed patients.[123,124] These products, generally administered as bolus injections, result in an increased plasma level of catalytically active nontransferrin bound iron and increased CKD-associated oxidative stress and inflammation. Indiscriminate use of IV preparations may hence increase risk of CV disease, promote microbial infections, and worsen diabetes and diabetic complications.[125] The alternative proposition is that if used judiciously, parenteral iron supplementation would usually be without major side effects, and possibly provide better outcomes than oral preparation.[126] This is perhaps the reason that IV iron is considered an integral part in the everyday management of anemia in patients with CKD.[127]

Various forms of IV iron are available for managing anemia of CKD that are not identical and differ in safety and tolerability based on differences in molecular size, degradation kinetics, and bioavailability.[50] All these forms are composed of a carbohydrate shell that stabilize and maintain iron in the core in a colloid form, controlling its release. The size of the iron core and type and density of the surrounding carbohydrate shell differs among the formulations. The carbohydrate shell can be either dextran or nondextran, which is an important parameter determining the tolerability. The low molecular weight iron dextran preparations are considered safer to high molecular weight preparations, but the newer IV irons, ferric gluconate, and iron sucrose,[128] which do not contain dextran overall have better safety profile compared to the dextran formulations while being superior to oral iron therapy as well. In July 2013, the FDA approved a new single-dose nondextran IV iron preparation − ferric carboxymaltose, which requires fewer clinic visits and venipunctures.[50,129] Ferric carboxymaltose is a robust and stable iron (III) hydroxide-carbohydrate complex, which lacks hypersensitivity associated with iron dextran, and can be infused in high doses in a single-IV infusion over 15 min.[77,130] The preparation has been observed to be more effective and better tolerated than oral iron for treatment of iron deficiency in nondialysis dependent-CKD patients.[129]

Erythropoiesis stimulating agent therapy in diabetic kidney disease

ESAs are widely used to treat anemias associated with a range of conditions, including CKD.[131] They have been an effective therapeutic agent in CKD anemia and seem to be more effective in patients with DKD, in whom anemia occurs early and is more sever compared to the nondiabetic counterparts.[41] They are not only useful in treating the anemia but could possibly slow the progression of CKD as well by reducing the oxidative stress and rendering tubular protection through antiapoptotic properties.[132] Some patients may however show an incomplete response to ESA therapy, and fail to maintain the recommended level of Hb.[133] Inadequate response in such patients with anemia and CKD could be attributable to short survival of RBCs, presence of unknown inhibitors of erythropoiesis in uremia, hyperparathyroidism, an accumulation of aluminum, and nutritional deficiency, such as that of iron, Vitamin B12, and folate.[98]

The timing of initiation of ESA therapy in dialysis patients may vary among patients. For some dialysis patients, ESAs may be started at lower Hb levels; whereas, ESAs can be started even at comparatively higher Hb levels for other dialysis patients, such as those with definite symptoms of anemia, or functional or other of QOL limitations related to anemia. Regardless, it is rational that ESA therapy in dialysis patients be started when Hb levels are <10 g/dL, even in the absence of symptoms directly attributable to anemia. This would help in reducing the need for transfusion.[134] Especially, when used to maintain the close specified range of 10−12 g/dL, ESAs can improve QOL and exercise tolerance, reduce the need for transfusions, and can alleviate the complications.[112] Early correction of anemia is beneficial in nondialysis CKD also. In nondialysis CKD, ESA initiation at Hb 10–11 g/dl compared with 8–9.9 g/dl is associated with reduced risk of blood transfusion and initial hospitalization.[135] This clearly signifies the need to start treatment early in all patients with CKD anemia.

Patients on ESA therapy should be evaluated for improvement in symptoms such as fatigue and physical functioning, and monitored for the ferritin and Hb levels. Hb concentrations should be monitored regularly after starting the ESA therapy − weekly until Hb is stable, followed by every other week, and then at least monthly so that doses of ESAs can be adjusted accordingly.[85] Ferritin levels >200 mcg/l, TSAT >20% and percentage of hypochromic RBCs <6% are required to be maintained.[118]

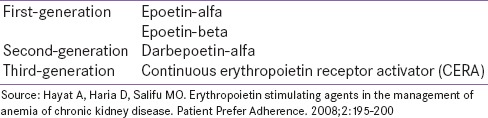

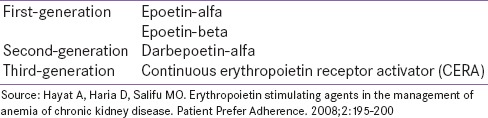

Types of erythropoiesis stimulating agents

Varieties of ESAs are available for use in patients with anemia of CKD, including epoetins and darbepoetin-alfa [Table 8]. All these preparations effectively increase the Hb but have distinguishable properties to influence the selection amongst them. The choice amongst them may be based on patient's clinical status and preferences, and characteristics of individual formulations.

Table 8.

Types of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents

First-generation erythropoiesis stimulating agents

Recombinant human EPO or epoetin, is the first ESA to be used clinically. It is a sialo glycoprotein hormone immunologically and biologically indistinguishable from the endogenous form. There are two forms of epoetins (epoetin-alfa and epoetin-beta), which differ in their glycosylation. These first-generation ESAs have a relatively shorter half-life and have traditionally been administered up to 3 times weekly to maintain adequate Hb levels in CKD patients on hemodialysis; later extended dosing interval of at least once per week were also tested. In CKD patients not yet on dialysis, epoetin-alfa is usually administered once weekly or once every other week.[72] Extended dosing intervals with maintenance doses of once-weekly, once every 2 weeks, and once every 3 or 4 weeks epoetin, have also been shown effective and well-tolerated in subgroups of nondialysis CKD/DKD patients with stable Hb level;[108,136] however, the inherent shorter half-life of epoetins still seems to limit trial of these extended intervals in larger population.

Second-generation erythropoiesis stimulating agents

The limitation with the first-generation ESAs led to the introduction of darbepoetin-alfa, the hyperglycosylated form, which confer greater metabolic stability in vivo owing to two additional N-linked carbohydrate chains attached to the protein backbone.[74] Darbepoetin-alfa has a half-life 3 times longer than that of epoetin, suggesting that it can be effectively administered less frequently than epoetin while maintaining similar EPO response.[71,137] Based on this, once-weekly darbepoetin-alfa is considered equipotent to thrice-weekly epoetin, with further proposition that stable patients on once a week epoetin can be converted to once every 2 weeks darbepoetin-alfa.[74] In addition, monthly administration of darb epoetin has also shown effectiveness in the treatment of anemia in dialysis and nondialysis patients with CKD.[138,139] This therapeutically translates into an advantage of better patient compliance. Typically, darbepoetin-alfa can hence be given once weekly in patients on dialysis, while the dosing may be reduced to up to once every 4 weeks in patients not yet on dialysis.[72,140] For maintenance, it can be administered every other week at beginning, followed by once monthly administration to maintain Hb target.[85]

Third-generation erythropoiesis stimulating agents

The latest in this category of ESAs is the continuous erythropoiesis receptor activator (CERA), which is the third-generation ESA, modified from EPO by insertion of a large pegylation chain to make it longer acting.[71,74] CERA has a significantly longer elimination half-life in vivo, allowing for extension of dosing intervals to once every 2 weeks or once every month. However, the limited clinical experiences with CERA suggest the predecessor – darbepoetin-alfa– could be chosen in subsets of patients with CKD anemia.[74,85]

Route of administration: Subcutaneous versus intravenous

ESAs can be administered through either subcutaneous (SC) or IV route. A number of factors may influence the choice of route, including staging of the CKD, properties of individual preparations, tolerability, and mainly the clinical profile of the patient. In dialysis patients, IV administration of ESAs is preferred, while those not yet on dialysis may preferably receive SC preparations since it results in less frequent injections.[109] Another factor for preference of IV route over SC route in hemodialysis population may be the small increased risk for pure red cell aplasia associated with SC versus IV route.[72] Even so, the route of administration may have limited influence on Hb levels. For instance, there is evidence that darbepoetin-alfa is associated with stable Hb concentrations regardless of the route of administration.[141]