Abstract

The rat heart expresses two myosin heavy chain (MHC) isoforms, β and α; these genes are arranged in tandem on the same chromosome. We have reported that an antisense (AS) β RNA starts in the intergenic (IG) region between β and α genes and extends to overlap the β gene. We propose that in adult rats, both the α sense and IG βAS RNA expression are activated by an IG bidirectional promoter and that the transcription of βAS RNA interferes with the sense β, resulting in low levels of β mRNA and high levels of α, a phenotype seen in a typical rat heart. A previous report examined the activity of the βAS promoter and showed that a 559 bp fragment of the βAS promoter (−2285 to −1726; relative to αMHC gene start site) injected into rat ventricle was activated in control heart, and decreased significantly in response to hypothyroidism (propylthiouracil induced) and diabetes (streptozotocin induced) and increased in hyperthyroid rats (T3 induced), similar in pattern to the endogenous βAS RNA. In the present paper, we demonstrate with electrophoretic mobility shift analyses that ventricular nuclear proteins are interacting with a nuclear factor 1/CAAT-binding transcription factor 1 (NF1/CTF1) binding site, and a supershift assay indicates that the protein binding at this site is antigenetically related to the CTF1/NF1 factor. Moreover, a mutation of the CTF1/NF1 site within the 559 bp promoter region nearly abolished promoter activity in vivo in control, STZ- and PTU-treated rats. Based on these findings, we conclude that the NF1 site is critical to βAS promoter regulation.

Two genes encoding cardiac myosin heavy chain (MHC) isoforms, β and α, are arranged in tandem on the rat chromosome 15, spanning 50 kb, and are separated by ~4.5 kb of intergenic DNA sequence (Mahdavi et al. 1984). Rat hearts typically express a predominance of the αMHC isoform and have high intrinsic contractility. Hypothyroid [propylthiouracil (PTU)-treated], calorie-restricted and diabetic [streptozotocin (STZ)-treated] rats express a significantly higher proportion of the β isoform (Nadal-Ginard & Mahdavi, 1989; Hasenfuss et al. 1991; Swoap et al. 1995; Schiaffino & Reggiani, 1996; Morkin, 2000; Rundell et al. 2004). The normal human heart predominantly expresses the β isoform, yet there is still an increase in βMHC and a decrease in αMHC isoforms observed in the failing human heart (Hasenfuss et al. 1991). The significance of the switch to the β isoform is generally considered to be a compensatory mechanism because although hearts with a higher proportion of βMHC have a lower rate of tension development in the ventricular muscle, they have a greater energy economy of force production (Alpert & Mulieri, 1982; Hasenfuss et al. 1991). We have reported that in the rat myocardium, in addition to the normal transcription of the αMHC and βMHC genes into pre-mRNA and corresponding mRNAs, an antisense RNA is also transcribed, which starts in the intergenic region between β and α genes and extends to overlap with the βMHC gene. We refer to this RNA as β antisense (βAS) RNA (Haddad et al. 2003).

The expression of this βAS RNA was positively correlated with the α pre-mRNA and negatively correlated with the β sense pre-mRNA (Haddad et al. 2003). Based on cardiac gene organization and their pattern of expression in relation to the βAS, we postulated that the intergenic region possesses bidirectional transcriptional activity that influences both the downstream αMHC (via its sense component) as well as the upstream βMHC gene expression (via the antisense component; Haddad et al. 2008). Little is known about the regulatory elements or transcription factors that can influence the activity of this bidirectional promoter. However, when we tested a 1340 bp sequence (−2285 to −945 relative to the αMHC transcription start site) of the intergenic βAS promoter in rat ventricle, we found that this promoter was activated in the control rodent heart, whereas it decreased greatly in response to PTU and STZ and increased ~9-fold in hyperthyroid (T3) rats, similar in pattern to the endogenous βAS RNA (Giger et al. 2007). However, mutation of the two putative retinoic acid receptor (RAR) binding sites (−1937 to −1923) within the 1340 bp promoter almost completely abolished reporter activity in all groups, and the STZ and PTU groups were no different from the vehicle group. Although the hyperthyroid (T3) group did respond to T3 treatment despite the mutation, there was only a threefold increase (Giger et al. 2007). We concluded that there is an intergenic promoter that is active in the AS direction and that a vital element is located within an important regulatory region spanning −1940 to −1920. The present study aims to examine this key regulatory site further and to determine the transcription factor(s) that may bind the promoter to activate the promoter and confer responsiveness to diabetes and thyroid hormone manipulations.

Methods

Ethical approval and animal models

Adult female Sprague–Dawley rats (~150–180 g body weight) were used for experimentally induced diabetes, hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism experiments spanning a period of 7 days (total number of rats used ~90). For procedures, general anaesthesia was induced with ketamine:acepromazine:xylazine (50:1:4 mg kg−1) injected intraperitoneally (i.p.). Experimentally induced type I diabetes was induced by a single dose of streptozotocin (STZ) administered via the jugular vein in anaesthetized rats immediately before the plasmid gene injection procedure. Streptozotocin (75 mg (kg body weight)−1) was diluted in vehicle solution consisting of 50 mm citrate buffer, pH 4.5. Rats administered only vehicle served as the control group. Hypothyroidism was induced by a daily propylthiouracyl (PTU) i.p. injection at a dose of 12 mg (kg body weight)−1, whereas hyperthyroidism was induced by a daily 3,5, 3′-triiodothyronine (T3; (150 μg (kg body weight)−1) i.p. injection. All animals were killed on the seventh experimental day, 6–8 h after the last PTU or T3 injection, by an overdose of sodium pentobarbitone (100 mg (kg body weight)−1 i.p.). This study followed the NIH Animal Care Guidelines and was approved by the University of California, Irvine, Animal Care and Use Committee.

DNA plasmid constructs

The reporter gene assay approach was used in order to test the βAS promoter activity in vivo. A 559 bp βAS promoter was subcloned into the pRL-null renilla luciferase vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Myosin light chain (MLC) promoter (a gift from Dr K. Esser, University of Kentucky) was subcloned into pGL3 basic firefly luciferase vector (Promega) and served as reference promoter to act as a control for transfection efficiency. For site-directed mutagenesis, standard recombinant DNA techniques and methods were used as previously described by Giger et al. (2005). The consensus sequence for putative binding site nuclear factor 1 (NF1) was identified using the Internet source (TESS; www.cbil.upenn.edu/cgi-bin/tess/tess). When necessary, DNA was sequenced using services provided by the University of California, Irvine, DNA core facility in order to verify the mutation within the insert.

Injection of DNA into the myocardium and reporter gene assay

The DNA injection into the myocardium was performed via a subdiaphragmatic approach. At the time of DNA injection, the rats were anaesthetized with ketamine:acepromazine:xylazine (50:1:4 mg (kg body weight)−1i.p.) and the abdomen was opened with a lateral incision below the diaphragm, using sterile techniques. The diaphragm was slightly pushed against the heart, and as upward pressure was placed on the sternum, the apex of the ventricle presented against the diaphragm. Then, 40 μl of sterile phosphate-buffered saline containing an equimolar mixture of two supercoiled DNA plasmids was injected through the diaphragm into the left ventricular wall using a 29 gauge needle attached to a 0.5 ml insulin syringe. A collar attached around the needle prevented the needle end from advancing into the ventricular chamber. After the injection, the abdomen was closed with sterile surgical sutures, and the rats were allowed to recover. Seven days after the plasmid injections, rats were killed; the ventricular apex portion was immediately frozen for reporter gene assays and the ventricular base portion was frozen for extraction of nuclear protein (described in the following subsection). The firefly luciferase and renilla luciferase activities were determined using the Dual Luciferase kit from Promega according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reaction chemiluminescence was determined using an analytical luminometer (BD Monolight 2010C, San Jose, CA, USA). Promoter activity is reported as the ratio of renilla activity (test promoter) divided by firefly luciferase activity (reference promoter).

Nuclear extraction of ventricular muscle tissue

Nuclear protein was extracted from a portion of the left ventricular muscle according to the method described by Blough et al. (1999). Briefly, frozen ventricle muscle tissue (400–700 mg) was homogenized in 35 ml of buffer 1 [10 mm Hepes, (pH 7.5), 10 mm MgCl2, 5 mm KCl, 0.1 mm EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.1% Triton X-100; 0.2 mm phenylmethylsulphonic fluoride (PMSF), 2.5 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 2.5 μg ml−1 leupeptin and 1 mm dithiothreitol (DTT)]. Homogenates were centrifuged for 5 min at 3000g at 4°C. The pellets were resuspended in 500–1000 μl of buffer 2 [20 mm Hepes (pH 7.5), 500 mm NaCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm EDTA (pH 8.0), 25% glycerol, 0.2 mm PMSF, 2.5 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 2.5 μg ml−1 leupeptin and 0.5 mm DTT]. The suspension was incubated on ice with intermittent mixing for 30 min and then centrifuged for 5 min at 4000g at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to an Amicon 2 ml Centricon filter unit (YM-10; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). An equal volume of binding buffer [20 mm Hepes (pH 7.9), 40 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 0.2 mm PMSF, 2.5 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 2.5 μg ml−1 leupeptin and 0.5 mm DTT] was added to the filter unit and centrifuged for 30 min at 4500g at 4°C. Another 500–1000 μl was added and centrifuged again for 3 min, and centrifugation was repeated until the concentrate achieved the desired volume (1 ml). Protein concentration of nuclear extract was determined using the Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA) protein assay with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Nuclear extract samples were stored at −80°C.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs)

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were used to determine binding of nuclear extract protein to the cis-regulatory elements of the rat type βAS MHC gene promoter. All oligonucleotide sequence probes were purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). After strand annealing, the double-stranded probe was end-labelled with [γ-32P]ATP (6000 Ci mmol−1) using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega). For each binding reaction, 20 μg nuclear extract was pre-incubated for 10 min at room temperature with 225 ng poly dI-dC homopolymer, which was used as a non-specific competitor, in a binding buffer containing 40 mm KCl, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm MgCl2, 7.5% glycerol, 0.05% bovine serum albumin and 20 mm Hepes (pH 7.9), in a total volume of 20 μl. For competition studies, the pre-incubation was carried out in the presence of 150× molar excess of either cold self, mutant or unrelated oligonucleotide (non-specific). At the end of the pre-incubation, 100 000 c.p.m. of labelled wild-type or mutated probes were added. Antibodies to potential nuclear proteins were added (4 μg) to the binding reactions to identify the possible transcription factor(s) comprising the specific DNA–protein complex. Reactions were then incubated for 30 min at room temperature. At the end of the reaction, 2 μl loading buffer (20% ficoll, 0.2% bromophenol blue and 0.2% xylene cyanol) was added, and the reaction mixtures were loaded on a 6% polyacrylamide gel, which was pre-electrophoresed at 20 mA per gel for 2 h. Electrophoresis was carried out in 0.5× tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer at constant current (30 mA) at room temperature for 3 h. Following electrophoresis, the gels were dried and visualized by phosphorimaging (Molecular Dynamics, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as means ± s.e.m. For bar graphs, comparisons within groups were made using a one-way analysis of variance with Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05; n ≥ 8 samples for each group.

Results

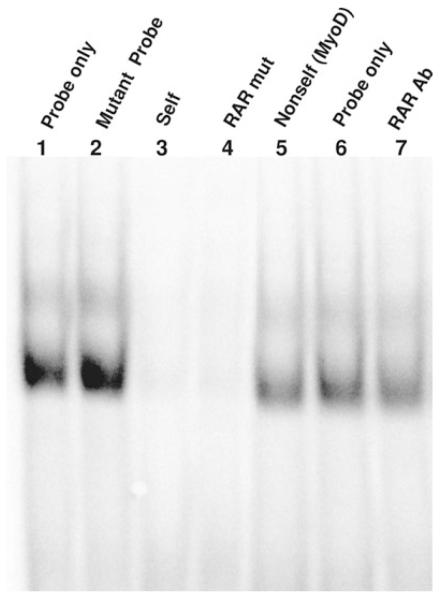

Previous findings indicated that a putative hormone receptor binding site, RAR [we call this site ‘RAR’ although RXR and thyroid (TR) are also potential factors/cofactors], is a key element for promoter activation and responsiveness to diabetes and hypothyroidism in rats (Giger et al. 2007). Therefore, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) in order to determine whether the transcription factors within rat cardiac nuclear protein extracts were binding specifically to a RAR site in the intergenic promoter. As a probe, we used a 35 bp sequence, termed RARwt, the core of which contains the putative RAR site (Fig. 1). Binding specificity was analysed through competition assays by pre-incubating extracts with 150-fold molar excess of unlabelled (cold) oligonucleotides: RARwt (self), RARmut or MyoD (non-self). Typically, we expect that if nuclear protein(s) binds the RAR site specifically, a DNA–protein complex will form, and a radiolabelled band will be detected in the gel. The pre-incubation with the cold self oligo is expected to compete with labelled oligo probe and only specific complexes would be expected to be disrupted and hence become undetected. In contrast, pre-incubation with cold mutant self, in which one or more nucleotides mapping within the consensus sequence is mutated, would not compete with the probe and thus the radioactive band on the gel would remain intact. The EMSA using RARwt as the radiolabelled probe did resolve several binding complexes, and specific complexes were disrupted when pre-incubated with cold self as expected (Fig. 1). However, these bands were also undetected when pre-incubated with the cold mutant oligo, indicating that DNA–protein complexes involve proteins that are not binding specifically at the RAR element. Further support that the nuclear factor is not binding specifically at the RAR site was confirmed by using a radioactive mutant RAR probe that showed a similar banding pattern to the RARwt probe. This finding was very surprising because we have previously reported (Giger et al. 2007) that promoter activity was virtually abolished when two adjacent RAR sites were mutated and concluded that the RAR binding site was vital in activation of the βAS gene.

Figure 1. The RAR site does not interact with nuclear proteins.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay using either a wild-type RAR or RARmut 35 bp radiolabelled oligonucleotide probe is represented. The probe for wild-type RAR was used in all samples except lane 2, which used RARmut probe. All reactions contained the same sample of nuclear protein extracted from control left ventricular muscles (20 μg). Binding specificity was analysed through competition assays by pre-incubating extracts with 150-fold molar excess of unlabelled oligonucleotides: wild-type RAR (self; lane 3); RARmut (lane 4); unrelated sequence containing a myogenic regulatory factor (MyoD) site (non-self; lane 5). An antibody to RARα (4 μg; C-20/sc-551, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added to the reaction in lane 7. The sequences of the double-stranded probes are as follows: wild-type RAR, GCTTGGACCTGACCCAGGCTGACCCAATGTTCTC; and RARmut, GCTTGGACCcGtaCCAGGCcGtaCCAATGTTCTCA. A site that is mutated is bold and underlined, while a mutated base is in lowercase.

In response to this unpredicted result, we used a larger sequence (80 bp; −1967 to −1887) as a probe, which includes not only the RAR sites but contains other putative sites as well, based on consensus comparisons derived from TESS. Several DNA–protein complex bands were detected. One band was identified with high specific affinity and labelled ‘Sp’ (Fig. 2), because the band was disrupted when challenged with unlabelled probe (self), while other bands (non-specific) remained intact. We tested serial mutations along this 80 bp sequence in order to determine which site is specifically bound by nuclear protein factors to form the specific complex (see Table 1) by pre-incubating with cold mutants. As shown in Fig. 2A, only the incubation with the cold CTF1/NF1mut competitor did not disrupt the specific band (Fig. 2A; lane 3), implying that the protein factors making up the specific complex were binding at this CTF1/NF1 (hereafter referred to simply as NF1) site, whereas pre-incubation with the other competitors, SEF1mut, RARmut, GRmut, GATAmut and TTF1mut (Fig. 2A; lanes 4–8), did compete in a similar manner to the cold self oligo. The fact that no specific complex was formed when we used a radioactive mutant NF1 oligo as the probe (Fig. 2A, lane 10) is further support for the suggestion that the nuclear protein is binding at the NF1 site.

Figure 2. The NF1 binding site specifically interacts with nuclear proteins.

A, serial mutations determine specific binding site. An EMSA using an 80 bp radiolabelled oligonucleotide probe ‘−1967 to −1887’ was performed, and all reactions contained the same sample of nuclear protein extracted from control left ventricular muscles (20 μg). Binding specificity was analysed through competition assays by pre-incubating extracts with 150-fold molar excess of various unlabelled oligonucleotides, as follows: −1967 to −1887 wild-type (self; lane 2); NF1mut (lane 3); RARmut (lane 4); GRmut (lane 5); GATAmut (lane 6); SEFmut (lane 7); and TTFmut (lane 8). Lanes 1 and 9 contain no competitors (probe only). The sample in lane 10 used a 80mer −1967 to −1887 containing a mutated NF1 site as the radioactive probe; it contained no other competitors. The arrow labelled ‘Sp’ indicates the location of the specific band. Underneath the picture of the gel is the sequence of the wild-type probe with the putative transcription factor binding sites underlined and labelled. Abbreviations: GR, glucocortoicoid receptor; RAR, retinoic acid receptor; SEF, soybean embryo factor; and TTF1, thyroid nuclear factor 1. The exact sequences of each oligonucleotide are shown in Table 1. B, intact NF1 binding site is important to formation of specific complex. All reactions contained the same sample of nuclear protein extracted (NE) from control left ventricular muscles (20 μg). With the exception of the sample in lane 1, samples in lanes 2–10 contained an 37 bp radiolabelled oligonucleotide probe, wild-type βAS −1959 to −1922. Lanes 1 and 2 contain no competitors (probe and NE only); lane 1 contains #2 NF1 mutant probe and lane 2 contains wild-type βAS −1959 to −1922. Binding specificity was analysed through competition assays by pre-incubating extracts with 150-fold molar excess of various unlabelled oligonucleotides, as follows: wild-type (self; lane 3); #2 NF1 mutant (lane 4); #3 NF1 mutant (lane 5); #4 NF1 mutant (lane 6); #1 NF1 double mutant (lane 7); #5 NF1 mutant (lane 8); #6 NF1 mutant (lane 9); and RAR mutant (lane 10). The arrows labelled ‘Sp’ indicate the location of the specific bands. The sequences of these mutants are as follows: wild-type, GGTTTTTGTCGCTTGGACCTGACCCAGGCTGACCCAA #1, GGTTTTTGTCGCTaGGACCTGACCaAGGCTGACCCAA #2, GGTTTTTGTCGCTaGGACCTGACCCAGGCTGACCCAA #3, GGTTTTTGTCGCaTGGACCTGACCCAGGCTGACCCAA #4, GGTTTTTGTCGCTTcGACCTGACCCAGGCTGACCCAA #5, GGTTTTTGTCGCTTGGAaCTGACCCAGGCTGACCCAA #6, GGTTTTTGTCGCTTGGtCCTGACCCAGGCTGACCCAA RARmut (80 bp) CAAAGCCT GGTTTTTGTCGCTTGGACCcGtaCCAGGCcGtaCCAATGTTCTCAGTGCCTTATCATGCCTCAAGAGCTTG Putative site sequences span 14 bases (bold), with wild-type being the wild-type NF1 site and #1 to #6 being a series of mutants within the NF1 site (mutated nucleotides are underlined and lowercase). The RAR mutant is 80 bp as used in Fig. 2A. C, NF1 antibody immunodepletes and causes supershifted bands of the specific complex. This EMSA used the same nuclear protein sample and wild-type sequence 37 bp −1959 to −1922, which is the same as the radioactive probe used in B. The lanes are as follows: ‘probe only’ has no competitor or antibody added (lane 1); wild-type −1959 to −1922 (self; lane 2); NF1 antibody (NF1 Ab, 4 μg; NF1c (H-300):sc-5567; lane 3); thyroid hormone receptor TRα antibody ‘215’ (4 μg; Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO, USA; lane 4); thyroid hormone receptor TRα antibody ‘216’ (4 μg; Affinity Bioreagents; lane 5); and NF1 antibody 2X (8 μg; NF1c (H-300):sc-5567, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA; lane 6). The arrows labelled ‘Sp’ indicate the location of the specific bands. The arrows on right labelled ‘SS’ indicate the supershifted bands at the top of the gel. Dotted arrows indicate bands supershifted using TRα ‘215’ antibody. (Pre-immune serum challenge is not shown.)

Table 1.

Sequences of oligonucleotides, wild-type and various mutations used in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (see Fig. 2A)

| –1967 SEF NF1 RAR/TR RAR/TR GR GATA TTF1 |

| CAAAGCCTGGTTTTTGTCGCTTGGACCTGACCCAGGCTGACCCAATGTTCTCAGTGCCTTATCATGCCCTCAAGAGCTTG |

| WT –1967 to –1887 |

| CAAAGCCTGGTTTTTGTCGCTTGGACCTGACCCAGGCTGACCCAATGTTCTCAGTGCCTTATCATGCCCTCAAGAGCTTG |

| SEFmut |

| CAAAGCCTGGTcTcTGTCGCTTGGACCTGACCCAGGCTGACCCAATGTTCTCAGTGCCTTATCATGCCCTCAAGAGCTTG |

| NF1/CTFmut |

| CAAAGCCTGGTTTTTGTCGCTaGGACCTGACCaAGGCTGACCCAATGTTCTCAGTGCCTTATCATGCCCTCAAGAGCTTG |

| RARmut |

| CAAAGCCTGGTTTTTGTCGCTTGGACCcGtaCCAGGCcGtaCCAATGTTCTCAGTGCCTTATCATGCCCTCAAGAGCTTG |

| GRmut |

| CAAAGCCTGGTTTTTGTCGCTTGGACCTGACCCAGGCTGACCCAATGcTCTCAGTGCCTTATCATGCCCTCAAGAGCTTG |

| GATAmut |

| CAAAGCCTGGTTTTTGTCGCTTGGACCTGACCCAGGCTGACCCAATGTTCTCAGTGCCTTgaCATGCCCTCAAGAGCTTG |

| TTF1mut |

| CAAAGCCTGGTTTTTGTCGCTTGGACCTGACCCAGGCTGACCCAATGTTCTCAGTGCCTTATCATGCCtTCAgGAGCTTG |

The top sequence shows the 80 bp sequence and location of all putative binding sites. Underlined characters depict boundaries of binding sites. Six different oligonucleotides harboured a mutation of a different binding site located serially along the sequence. WT is the wild-type sequence. A site that is mutated is bold and underlined, while a mutated base is in lowercase. Putative transcription factor consensus binding sites were identified using Internet sources (TESS, MatInspector, www.cbil.upenn.edu/cgi-bin/tess/tess)

According to the internet source TESS consensus sequence comparisons, the NF1 element spans 14 bp, with the distal end overlapping part of the proximal putative RAR site. We verified the specificity of binding the NF1 site by using a series of single mutations across the proximal region of the 14 bp NF1 site (Fig. 2B). The ‘#2 NF1 mutation’ is a single mutation similar to the original double NF1 mutation used in Fig. 2A, but without the mutated nucleotide in the distal region of the site. Unlike the results using the wild-type probe, there was no specific complex formed using the radioactive ‘#2 NF1 mutant’ as a probe. Competition assays using serial mutations across the proximal region of the NF1 site showed that mutation of four of the most proximal five nucleotides did not disrupt the specific band, indicating that these nucleotides, albeit to varying degrees, are vital for the site to be recognized by specific protein complex. The cold competition with either wild-type sequence (self), ‘#5 NF1 mutant’ or the original RAR mutant did disrupt the specific band. The single mutations ‘#2 NF1 mutant’ and ‘#4 NF1 mutant’ appeared to have similar results to the original NF1 double mutant. Using the wild-type probe, we showed that the addition of NF1 antibody (lanes 3 and 6) disrupted the specific complexes and resulted in the concomitant appearance of supershifted bands at the top of the gel. The addition of two thyroid hormone receptor (TR) antibodies did not cause the disruption of the specific bands, although antibody TR(215) showed faint retarded bands at the top of the gel (Fig. 2C). These results strongly suggest that the protein(s) comprising the specific protein–DNA complex are antigenically related to NF1, and somewhat to TR(215) as well.

In order to substantiate whether the NF1 binding site at −1946 to −1933 of the βAS promoter is indeed a critical binding site for promoter activation, we tested a mutated promoter in vivo (Fig. 3). We created a mutation within the NF1 site (same mutation as the NF1 double mutant used for EMSAs; see Fig. 2A, lane 3, and Fig. 2B, lane 7) of a 559 bp βAS promoter (559 NF1mut) and transfected this promoter-driven luciferase reporter plasmid into ventricles of control, diabetic, hypothyroid and hyperthyoroid rats. In Fig. 3 and as shown in a previous report (Giger et al. 2007), the wild-type 559 bp (−2285 to −1726) promoter activity in diabetic rats (STZ) was almost half the level seen in control rats (vehicle); and in hypothyroid rats (PTU), the activity was about one-third of control levels. In contrast, in hyperthyroid rats (T3), activity increased dramatically by about 6.5-fold. When we tested the 559 NF1mut promoter, the reporter activity was virtually abolished in control, diabetic and hypothyroid rats. In fact, as a result of the NF1 mutation, these reporter activities were not greater than that measured using a promoterless reporter vector (pRL null, Promega; data not shown). Thus, it appears that the NF1 binding site is clearly important to activate βAS promoter in control rat hearts and possibly in directing responsiveness to hypothyroidism and diabetes. However, despite the NF1 mutation, the promoter activity in hyperthyroid rats was still significantly up-regulated about ninefold over that of the control sample.

Figure 3. Mutation of NF1 abolishes βAS promoter activity in hearts of control, diabetic and hypothyroid rats.

Bar graph shows a comparison of the promoter activity of a wild-type (559WT) 559 bp (−2285 to −1726) βAS promoter and a 559 bp promoter harbouring a 2 bp mutation that obliterates the NF1 binding site (559 NF1mut). Heart samples from control (vehicle-treated; n = 17 wild-type and 9 mutated), diabetic (STZ; n = 17 wild-type and 9 mutated), hypothyroid (PTU; n = 12 wild-type and 8 mutated), and hyperthyroid rats (T3; n = 9 wild-type and 10 mutated) are compared. Bars represent the ratio of reporter activity of βAS promoter divided by reporter activity of the reference promoter (MLC). *P < 0.05 versus vehicle group (ANOVA). The diagram depicts the 4.5 kb intergenic spacer between the tandem cardiac MHC β and α genes which harbours the proposed bidirectional promoter (BDP) that has transcriptional activity in the sense direction for αMHC gene (αP) and in the antisense direction for the βAS (β(as)P). βP denotes the β sense promoter. The intergenic region is shown with a +1 that denotes the start site of the αMHC gene, and the backward arrows denote the start sites of the antisense β transcript. Antisense promoter fragment −2285 to −1726 (559 bp βAS) as derived from intergenic gene sequence was tested in control rat hearts; the X denotes relative location of the NF1 mutation.

Discussion

The present study aimed to examine further a vital sequence in theβAS MHC promoter that confers promoter activation and may play a role in its responsiveness to diabetes and thyroid hormone manipulations. The βAS promoter is within the intergenic sequence between αMHC and βMHC genes and composes part of what we theorize to be a common bidirectional promoter which activates both αMHC and βAS transcription, the latter of which inhibits β sense transcription. The regulation of MHC isoform gene expression potentially can exert a profound influence on both the contractile and the energetic properties of the heart within any given species. Evidence suggests that the MHC isoforms are regulated at the transcriptional level, yet the molecular mechanisms involved are unknown. We are interested in deciphering the mechanism by which the αMHC and βMHC gene expressions are regulated, and the βAS promoter is specifically examined in the present paper.

Myosin heavy chain is an integral contractile component of the muscle sarcomere, and the enzymatic activity of the MHC ATPase is fundamental in determining the rate of cross-bridge cycling, and thus the speed of muscle contraction. Adult mammalian ventricular muscle expresses two genes encoding MHC isoforms designated as α and β (Hoh et al. 1979; Mahdavi et al. 1982; Lompre et al. 1984; Hasenfuss et al. 1991; Morkin, 2000), which are arranged in tandem on the rat chromosome 15, spanning 50 kb, and are separated by ~4.5 kb of intergenic DNA sequence (Mahdavi et al. 1984). The functional significance of the two isoforms is that the β isoform is associated with a relatively low ATPase activity and low rate of contraction, yet has a greater energy economy of force production, whereas the α isoform is associated with a high ATPase activity and a high rate of contraction.

Normal adult rat hearts typically express the fast αMHC isoform and consequently have a higher rate of contraction. Hypothyroid, calorie-restricted and diabetic rats express a significantly higher proportion of the β isoform (Nadal-Ginard & Mahdavi, 1989; Hasenfuss et al. 1991; Swoap et al. 1995; Schiaffino & Reggiani, 1996; Morkin, 2000; Rundell et al. 2004). The normal human heart predominantly expresses the β isoform, yet the human heart does express αMHC, up to 23–34% (Lowes et al. 1997; Nakao et al. 1997), and the level of α is significantly decreased, with a concomitant increase in β, in failing human hearts (Hasenfuss et al. 1991), e.g. in diabetic cardiomyopathy (Lowes et al. 1997; Nakao et al. 1997; Lowes et al. 2002).

What is the functional significance of the isoform switch to βMHC?

In rats, the switch to βMHC is linked to a decreased rate of cross-bridge cycling and a lower rate of tension development in the ventricular muscle, but a decreased energy cost for tension production (Alpert & Mulieri, 1982; Hasenfuss et al. 1991; Rundell et al. 2004). During the early stages of diabetes, for example, there is a shift in the energy substrate supply and utilization within the heart, which results in impaired cardiac efficiency; thus, a switch towards βMHC, i.e. a more energy-efficient contractile unit, is believed to be triggered as a compensatory response.

We have reported that in the rodent myocardium, in addition to the normal transcription of the αMHC and βMHC genes into the pre-mRNA and corresponding mRNAs, we detected the transcription of an antisense RNA which starts in the intergenic region between β and α genes and extends to overlap with the βMHC gene (Haddad et al. 2003), and thus is called β antisense (βAS) RNA. Streptozotocin-induced diabetes caused an increase in β sense pre-mRNA and a marked decrease in both the α sense and the βAS RNAs. The inverse relationship between β mRNA and βAS RNA suggests that the expression of the βAS RNA interferes with the accumulation of the β sense pre-mRNA into mature mRNA. Also, the βAS RNA is positively correlated with the α sense pre-mRNA, suggesting that these RNA species are controlled by common intergenic promoter elements which are capable of affecting transcription in both directions. Our aim is to discern what promoter sequences and corresponding transcription factors are important for the transcription of βAS RNA.

Does NF1 play a role in the antithetical regulation of cardiac MHC isoforms?

The βAS promoter originates in the intergenic sequence and is part of the bidirectional promoter that confers the antithetical expression of the two cardiac MHC isoforms, α and β. Previously, we tested a 1340 bp sequence (−2285 to −945 relative to the αMHC transcription start site) of the intergenic βAS promoter in rat ventricle, and we found that this promoter was activated in the control rodent heart, whereas it decreased greatly in response to PTU and STZ and increased about ninefold in hyperthyroid rats, similar in pattern to the endogenous βAS RNA (Giger et al. 2007). We also reported that a vital element is located within a regulatory region spanning −1940 to −1920. The findings presented here determined that the NF1 site is only element in this region that interacts with rat cardiac nuclear protein extracts in the EMSA assay. Also, the mutation of the NF1 site nearly abolished the βAS promoter activity in control rat hearts in vivo.

The potential role that NF1 plays in activating the intergenic promoter is further highlighted by comparing sequence alignment across species. Table 2 shows a comparison of the sequence of the intergenic region examined in this paper across five different species: human, rabbit, hamster, mouse and rat. Although many base pairs are conserved across species, there are differences that render the NF1/CTF site absent in the promoters of the rabbit and human sequences as well as those of the guinea-pig, dog, cow and monkey (not shown). This is most intriguing because the hearts of all of these species predominantly express the β isoform (Bhatnagar et al. 1984; VanBuren et al. 1995; Lowes et al. 1997), whereas the adult heart of the hamster, mouse and rat predominantly expresses the αMHC isoform. One may speculate that the species-specific isoform differences may be due, in part, to strong antisense promoter activity in the rat, mouse and hamster but that the βAS promoter is not highly active or has low activity in the larger mammals. Moreover, the absence of the NF1 site in this key region may cause the bidirectional promoter to become less active in these larger species. Whether or not the NF1 site contributes significantly to cardiac isoform expression in different species or in different conditions remains to be demonstrated, but our data suggest that an intact NF1 site is vital to βAS promoter activity in adult control rat hearts.

Table 2.

The NF1 site is not conserved across species

|

Underlined nucleotides depict boundaries for the CTF/NF1 site. Shaded nucleotides are those that were mutated in the in vivo promoter analyses, both of which are conserved in all species. Conserved nucleotides across all 5 species are indicated by #. The TESS analyses of these sequences show that the CTF1/NF1 site is conserved in the rat, mouse and hamster but not in the rabbit and human. Bold text depicts the bases that contribute to loss of the NF1/CTF1 site in these species.

Nuclear factor 1 constitutes a family of polypeptide isoforms designated as NF1a, NF1b, NF1c and NF1x, which are encoded by four different genes (Osada et al. 2005). Nuclear factor 1 is usually considered to have ubiquitious expression in most tissues and it is thought to have dual roles in both eukaryotic transcription and DNA replication. Not only is NF1 known to act as a transcription-initiating factor associated with RNA polymerase II promoters (Santoro et al. 1988), but evidence suggests that the NF1 family can act in a tissue-specific manner as well. In fact, NF1 isoform genes are subject to alternative splicing, where the less conserved C-terminal domains bear specific functions (Osada et al. 2005). For example, there are several reports which indicate a role for the NF1 binding site in the expression of smooth muscle MHC (White & Low, 1996), and specifically for restricting expression of skeletal muscle troponin C and muscle-specific aldolase to fast fibres only (Gahlmann & Kedes, 1993; Salminen et al. 1995; Johanson et al. 1999; Spitz et al. 2002). Collectively, these findings demonstrate the importance of the role of NF1 in regulating muscle genes and directing expression in certain fibre types. Whether NF1 is binding the NF1 site in the βAS promoter or what signalling pathway activates NF1 remains unknown.

Thyroid hormone affects cardiac MHC expression independently of NF1

It has been known for decades that thyroid hormone is a very potent regulator of all the MHC isoforms (Ojamaa et al. 1996, 2000; Ojamaa & Klein, 1991; Subramaniam et al. 1993). The data in this paper clearly demonstrated that thyroid hormone affected the βAS promoter activity independently of the NF1 site because the 559 NF1mut promoter activity was still increased in response to thyroid hormone treatment. Also, a shorter αMHC promoter (−612 to +73), which does not include the NF1 site studied in the present work, is also responsive to diabetes and sensitive to thyroid state (data not shown). Given the fact that the NF1 mutation abolished βAS promoter activity below basal levels in control, diabetic and hypothyroid rats (Fig. 3), we cannot presume that the NF1 binding site confers the hormone responsiveness of the intergenic bidirectional promoter. Notwithstanding, there is evidence to suggest that NF1 may play a vital role in the transcriptional activation of hormone-sensitive genes (Ortiz et al. 1999; Belikov et al. 2004). It has been reported that insulin not only up-regulates expression of NF1 (Ortiz et al. 1999) but also stimulates transactivation by NF1 of insulin-responsive genes such as thyroperoxidase and glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) (Cooke & Lane, 1999a,b; Ortiz et al. 1999). In the case of the βAS promoter, NF1 may interact with the RAR/TR to activate the promoter. The two RAR/TR sites are in very close proximity to the NF1 site, and the EMSA indicated a partially supershifted band using the TR antibody, suggesting that TR protein is binding this sequence as well.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings suggest that the NF1 binding site is important in the regulation of the βAS gene in adult rat hearts. Thyroid hormone is a potent regulator of the antisense promoter and affects its activity in an NF1-independent manner. We also suggest that the NF1 site in the intergenic bidirectional promoter may contribute to the species-specific expression of the α or β cardiac MHC isoforms across different species.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support of the American Diabetes Association’s Amaranth Diabetes Fund (J.M.G.) and NIH grant HL-073473 (K.M.B.).

References

- Alpert NR, Mulieri LA. Increased myothermal economy of isometric force generation in compensated cardiac hypertrophy induced by pulmonary artery constriction in the rabbit. A characterization of heat liberation in normal and hypertrophied right ventricular papillary muscles. Circ Res. 1982;50:491–500. doi: 10.1161/01.res.50.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belikov S, Åstrand C, Holmqvist PH, Wrange O. Chromatin-mediated restriction of nuclear factor 1/CTF binding in a repressed and hormone-activated promoter in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3036–3047. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.7.3036-3047.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar GM, Walford GD, Beard ES, Humphreys S, Lakatta EG. ATPase activity and force production in myofibrils and twitch characteristics in intact muscle from neonatal, adult, and senescent rat myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1984;16:203–218. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(84)80587-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blough E, Dineen B, Esser KA. Extraction of nuclear proteins from striated muscle tissue. BioTechniques. 1999;26:202–204. doi: 10.2144/99262bm05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke DW, Lane MD. The transcription factor nuclear factor I mediates repression of the GLUT4 promoter by insulin. J Biol Chem. 1999a;274:12917–12924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke DW, Lane MD. Transcription factor NF1 mediates repression of the GLUT4 promoter by cyclic-AMP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999b;260:600–604. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahlmann R, Kedes L. Tissue-specific restriction of skeletal muscle troponin C gene expression. Gene Expr. 1993;3:11–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giger J, Qin AX, Bodell PW, Baldwin KM, Haddad F. Activity of the β-myosin heavy chain antisense promoter responds to diabetes and hypothyroidism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H3065–H3071. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01224.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giger J, Haddad F, Qin AX, Zeng M, Baldwin KM. The effect of unloading on type I MHC gene regulation in rat soleus muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1185–1194. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01099.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad F, Bodell P, Qin A, Giger J, Baldwin KM. Role of antisense RNA in coordinating cardiac myosin heavy chain gene switching. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37132–37138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305911200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad F, Qin AX, Bodell PW, Jiang W, Giger JM, Baldwin KM. Intergenic transcription and developmental regulation of cardiac myosin heavy chain genes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H29–H40. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01125.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenfuss G, Mulieri LA, Blanchard EM, Holubarsch C, Leavitt BJ, Ittleman F, Alpert NR. Energetics of isometric force development in control and volume-overload human myocardium. Comparison with animal species. Circ Res. 1991;68:836–846. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.3.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoh JFY, Yeoh GPS, Thomas MAW, Higginbottom L. Structural differences in the heavy chains of rat ventricular myosin isoenzymes. FEBS Lett. 1979;97:330–334. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(79)80115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanson M, Meents H, Ragge K, Buchberger A, Arnold HH, Sandmoller A. Transcriptional activation of the myogenin gene by MEF2-mediated recruitment of Myf5 is inhibited by adenovirus E1A protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;265:222–232. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lompre A-M, Nadal-Ginard B, Mahdavi V. Expression of the cardiac ventricular α- and β-myosin heavy chain genes is developmentally and hormonally regulated. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:6437–6446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowes BD, Gilbert EM, Abraham WT, Minobe W, Larrabee P, Ferguson D, Wolfel EE, Lindenfeld JA, Tsvetkova T, Robertson AD, Quaife RA, Bristow MR. Myocardial gene expression in dilated cardiomyopathy treated with beta-blocking agents. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1357–1365. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowes BD, Minobe W, Abraham WT, Rizeq MN, Bohlmeyer TJ, Quaife RA, Roden RL, Dutcher DL, Robertson AD, Voelkel NF, Badesch DB, Groves BM, Gilbert EM, Bristow MR. Changes in gene expression in the intact human heart. Down-regulation of α-myosin heavy chain in hypertrophied, failing ventricular myocardium. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2315–2324. doi: 10.1172/JCI119770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavi V, Chambers AP, Nadal-Ginard B. Cardiac α- and β-myosin heavy chain genes are organized in tandem. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:2626–2630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.9.2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavi V, Periasamy M, Nadal-Ginard B. Molecular characterization of two myosin heavy chain genes expressed in the adult heart. Nature. 1982;297:659–664. doi: 10.1038/297659a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morkin E. Control of cardiac myosin heavy chain gene expression. Microsc Res Tech. 2000;50:522–531. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20000915)50:6<522::AID-JEMT9>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal-Ginard B, Mahdavi V. Molecular basis of cardiac performance. Plasticity of the myocardium generated through protein isoform switches. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1693–1700. doi: 10.1172/JCI114351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao K, Minobe W, Roden R, Bristow MR, Leinwand LA. Myosin heavy chain gene expression in human heart failure. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2362–2370. doi: 10.1172/JCI119776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojamaa K, Kenessey A, Shenoy R, Klein I. Thyroid hormone metabolism and cardiac gene expression after acute myocardial infarction in the rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;279:E1319–E1324. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.6.E1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojamaa K, Klein I. Thyroid hormone regulation of alpha-myosin heavy chain promoter activity assessed by in vivo DNA transfer in rat heart. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;179:1269–1275. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91710-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojamaa K, Klemperer JD, MacGilbray SS, Klein I, Samarel AM. Thyroid hormone and hemodynamic regulation of β-myosin heavy chain promoter in the heart. Endocrinology. 1996;137:802–808. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.3.8603588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz L, Aza-Blanc P, Zannini M, Cato AC, Santisteban P. The interaction between the forkhead thyroid transcription factor TTF-2 and the constitutive factor CTF/NF-1 is required for efficient hormonal regulation of the thyroperoxidase gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15213–15221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.15213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada S, Imagawa M, Nishihara T. Organization of gene structure and expression of nuclear factor 1 family in rat. DNA Seq. 2005;16:151–155. doi: 10.1080/10245170500059024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundell VLM, Geenen DL, Buttrick PM, de Tombe PP. Depressed cardiac tension cost in experimental diabetes is due to altered myosin heavy chain isoform expression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H408–H413. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00049.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen M, Spitz F, Fiszman MY, Demignon J, Kahn A, Daegelen D, Maire P. Myotube-specific activity of the human aldolase A M-promoter requires an overlapping binding site for NF1 and MEF2 factors in addition to a binding site (M1) for unknown proteins. J Mol Biol. 1995;253:17–31. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro C, Mermod N, Andrews PC, Tjian R. A family of human CCAAT-box-binding proteins active in transcription and DNA replication: cloning and expression of multiple cDNAs. Nature. 1988;334:218–224. doi: 10.1038/334218a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiaffino S, Reggiani C. Molecular diversity of myofibrillar proteins: gene regulation and functional significance. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:371–423. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitz F, Benbacer L, Sabourin JC, Salminen M, Chen F, Cywiner C, Kahn A, Chatelet F, Maire P, Daegelen D. Fiber-type specific and position-dependent expression of a transgene in limb muscles. Differentiation. 2002;70:457–467. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2002.700808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam A, Gulick J, Neumann J, Knotts S, Robbins J. Transgenic analysis of the thyroid-responsive elements in the α-cardiac myosin heavy chain gene promoter. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:4331–4336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swoap SJ, Haddad F, Bodell P, Baldwin KM. Control of β-myosin heavy chain expression in systemic hypertension and caloric restriction in the rat heart. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1995;269:C1025–C1033. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.4.C1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanBuren P, Harris DE, Alpert NR, Warshaw DM. Cardiac V1 and V3 myosins differ in their hydrolytic and mechanical activities in vitro. Circ Res. 1995;77:439–444. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.2.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SL, Low RB. Identification of promoter elements involved in cell-specific regulation of rat smooth muscle myosin heavy chain gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15008–15017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.15008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]