Abstract

Specific gene expressions of host cells by spontaneous STAT6 phosphorylation are major strategy for the survival of intracellular Toxoplasma gondii against parasiticidal events through STAT1 phosphorylation by infection provoked IFN-γ. We determined the effects of small molecules of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) on the growth of T. gondii and on the relationship with STAT1 and STAT6 phosphorylation in ARPE-19 cells. We counted the number of T. gondii RH tachyzoites per parasitophorous vacuolar membrane (PVM) after treatment with TKIs at 12-hr intervals for 72 hr. The change of STAT6 phosphorylation was assessed via western blot and immunofluorescence assay. Among the tested TKIs, Afatinib (pan ErbB/EGFR inhibitor, 5 µM) inhibited 98.0% of the growth of T. gondii, which was comparable to pyrimethamine (5 µM) at 96.9% and followed by Erlotinib (ErbB1/EGFR inhibitor, 20 µM) at 33.8% and Sunitinib (PDGFR or c-Kit inhibitor, 10 µM) at 21.3%. In the early stage of the infection (2, 4, and 8 hr after T. gondii challenge), Afatinib inhibited the phosphorylation of STAT6 in western blot and immunofluorescence assay. Both JAK1 and JAK3, the upper hierarchical kinases of cytokine signaling, were strongly phosphorylated at 2 hr and then disappeared entirely after 4 hr. Some TKIs, especially the EGFR inhibitors, might play an important role in the inhibition of intracellular replication of T. gondii through the inhibition of the direct phosphorylation of STAT6 by T. gondii.

Keywords: Toxoplasma gondii, growth inhibition, small molecule, tyrosine kinase inhibitor, EGFR, Afatinib, STAT6 phosphorylation

INTRODUCTION

Toxoplasma gondii is a ubiquitous obligate intracellular parasite, which infects warm-blooded animals, including humans. It is a zoonotic pathogen widespread in nature [1,2]. Approximately one-third of humans worldwide are chronically infected with T. gondii [2,3]. Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis is the most common cause (30-50%) of infective posterior uveitis, and one of the major causes of visual impairment in high T. gondii endemic regions of American and European countries [4].

Most uveitis specialists agree that antibiotic treatment of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis is reasonable because antibiotics can reduce the number of recurrences and facilitate the resolution of inflammation; however, a consensus on the utility of antibiotics has not been reached [5,6]. The most frequent drug regimen for ocular toxoplasmosis consists of pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine in addition to corticosteroids [7]. However, this classic treatment may have severe risks that depend on the patient’s susceptibility to drug toxicity or allergic reactions such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome [8,9].

T. gondii rapidly invades the host cells less than 10 seconds, wherein the parasite forcibly indents and modifies the host cell’s plasma membrane, thereby creating the parasitophorous vacuole (PV) in which it develops [10]. In this process, rhoptry proteins (ROPs) have a very important role in creating the parasitophorous vacuole membrane (PVM) within the host cells. Among the ROPs (ROP1-ROP21), ROP2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 11, 16, 17, and 18 have kinase domains in their C-terminal halves [11]. Therefore, these proteins may function in signal transduction across the PVM to maintain the host cell-parasite relationship and are a candidate target for a novel drug. The spontaneous signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 6 phosphorylation and subsequent specific gene expression of host cells are the major strategies for the survival of intracellular T. gondii against parasiticidal events which occur through STAT1 phosphorylation induced by the provoked IFN-γ in an infection [12,13].

Tyrosine kinases (TK) are enzymes responsible for the activation of many proteins across the signal transduction cascades. The proteins are activated by the addition of a phosphate group to the protein. A tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) is a pharmaceutical drug that inhibits those TK. Recently, large numbers of small molecules of TKI have been developed for chemotherapy of cancers [14,15] and expanded their efficacy for treatment of infectious diseases [16,17]. After a preliminary screening study, we choose 3 target TKI drugs, including Erlotinib hydrochloride, Afatinib, and Sunitinib. In brief, Erlotinib is a drug used to treat non-small cell lung cancer and pancreatic cancer and is a reversible TKI, which acts on the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [18]. Afatinib is a drug approved for treatment of EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer and is a small molecule kinase inhibitor that causes irreversible inhibition of EGFR and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) [19]. Sunitinib is an oral, small-molecule, multi-targeted receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitor that was approved to treat renal cell carcinoma and imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors [20].

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effects of several TKIs on the growth inhibition of intracellular T. gondii and the relationship with STAT1 and STAT6 phosphorylation in the RPE cell line ARPE-19.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell line and parasite

ARPE-19 cells (ATCC® CRL-2302TM, Manassas, Virginia, USA) were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) containing 2 µM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 0.25 µg/ml fungizone and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco Life Technologies, Grand Island, New York, USA). Tachyzoites of the RH strain of T. gondii were intraperitoneally injected into BALB/c mice, and peritoneal exudates were collected immediately after the death of the mice at the 4th day with Dulbecco’s PBS (DPBS) (Invitrogen).

Drugs and antibodies

Afatinib (BIBW2992) and Erlotinib (OSI-420) were purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, Texas, USA). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), pyrimethamine, and Sunitinib malate (SU 11248) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). Bovine serum albumin was purchased from Bovogen Biologicals (Melbourne, Australia).

Antibodies against Phospho-STAT1 (Tyr701) (58D6), Phospho-STAT2 (Tyr690), Phospho-STAT3 (Ser727), Phospho-STAT5 (Tyr694) (C11C5), Phospho-STAT6 (Tyr641), and β-actin were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, Massachusetts, USA). Antibodies against STAT1 p91(c-111), STAT6 (M-20), Phospho-JAK1 (Tyr1022/Tyr1023), and Phospho-JAK3 (Tyr980) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, California, USA). FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody, TRTIC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody, and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibodies were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Mouse Tg563 monoclonal antibody was cloned in our laboratory.

Assay of drugs on intracellular multiplication of T. gondii

ARPE-19 cells were plated on 12 mm cover glasses in 24-well plates (Costar, New York, USA) at 0.5×105 cells/0.5 ml/well. After 24 hr of plating, the plate was washed once with pre-warmed DPBS and replaced with fresh medium containing 10% FBS. Fresh tachyzoites of the RH strain of T. gondii were added to the plates at 5.0×105 T. gondii/0.5 ml/well. After 1 hr of infection, uninvaded parasites were washed with prewarmed DPBS and refilled with fresh pre-warmed medium containing 10% FBS. The drugs were added at 1 hr post infection and at 12-hr intervals post infection until 72 hr. At the indicated time point of post infection, the cells in different wells were fixed with ice-cold methanol (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for 5 min and stained with Giemsa solution (Sigma Aldrich). Cells on cover glasses can be rewetted and observed under 400×objective fields. The number of parasites per PV was counted in each stained well with 5 random high-power fields (×400).

Effects of drugs on signaling pathways of host cells invaded by parasites

ARPE-19 cells were plated in 6-well plates (Costar) at 2.0×105 cells/3.0 ml/well. After 24 hr of plating, the plate was washed once with pre-warmed DPBS and replaced with fresh medium containing 10% FBS, and the drugs were added to the indicated wells. At 1 hr later, the indicated wells were respectively added with drugs or challenged with fresh tachyzoites at 2.0×106 T. gondii/2.0 ml/well. After 1 hr of infection, drugs were added to the indicated wells. Briefly, 5 groups were tested in this assay. The 1st group was as control, in which there were no parasite infections and no drug treatment. In the 2nd group, cells were only treated with drug. In the 3rd group, cells were treated with drug and 1 hr later challenged with fresh tachyzoites. In the 4th group, cells were only challenged with tachyzoites. In the 5th group, cells were challenged with tachyzoites and 1 hr later treated with drug.

At 2, 4, and 8 hr of post-infection, the cells were lysed with 200 µl/well of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 1% β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma Aldrich), 10% glycerol (Junsei, Tokyo, Japan), and 1% bromophenol blue. The total cell lysate was analyzed by western blot. The total cell lysate was dissolved using 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Whatman GmbH, Dassel, Germany) by a mini-protean Tetra system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA). The membrane was incubated with 5% skim milk (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Missouri, USA) in PBS with 0.5% Tween 20 (PBST) for 1 hr. Following a PBST wash, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies in PBST with 5% skim milk at room temperature for 2 hr. The membranes were then incubated with secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase in PBST with 5% skim milk for 2 hr). The signals were detected with an ECL Western blot kit (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA).

Immunofluorescence assay

Host cells on 12 mm cover glasses were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde (Sigma Aldrich) in DPBS for 5 min and then permeabilized by 0.05% Triton X-100 for 5 min. The cells were incubated with mouse Tg563 and rabbit anti-phospho-STAT6 (Tyr641) antibodies diluted in 1:200 of 3% BSA/DPBS for 1 hr, which was followed by FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody and TRTIC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody diluted in 1: 500.

RESULTS

Inhibition of intracellular multiplication of T. gondii in ARPE-19 cells by tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI)

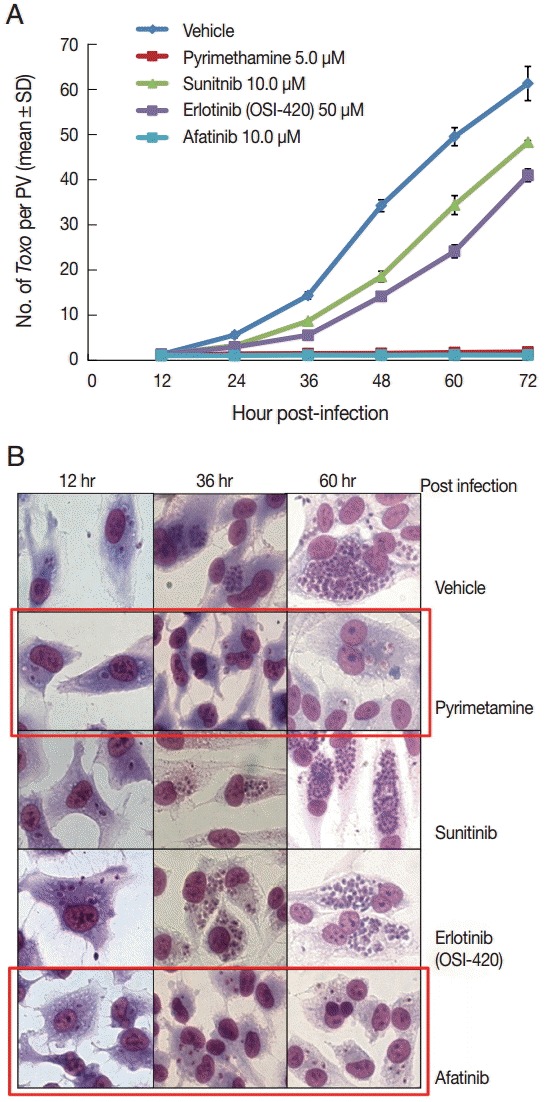

DMSO was used as a solvent for the TKIs and added to the negative vehicle control. Pyrimethamine 5 µM was used as the positive control. The highest concentrations of the 3 TKIs which did not detach the host cells from cover glasses were applied in this experiment. The concentrations of Afatinib, Erlotinib, and Sunitinib were 10, 50, and 10 µM, respectively (Fig. 1). At 1 hr post infection, the drugs were added to the wells, and at 12-hr interval post infection until 72 hr the cells in the indicated wells were stained with Giemsa. The number of parasites per PVM was counted in each stained well with 5 random high-power fields (×400). Fig. 1A shows the counting results as the mean±SD from duplicate wells. Fig. 1B shows a representative result of Giemsa stain. These results showed that Afatinib 10 µM completely inhibited the intracellular growth of T. gondii similar to the inhibitory effect of pyrimethamine 5 µM, whereas Erlotinib 50 µM and Sunitinib 10 µM did not inhibit the intracellular growth of the parasite.

Fig. 1.

Afatinib efficiently inhibits the intracellular multiplication of T. gondii RH tachyzoites in ARPE-19 cells. (A) The number of parasites per parasitophorous vacuolar membrane (PVM) after Giemsa staining. DMSO was used as the negative vehicle control, whereas pyrimethamine 5 μM was used as the positive control. The highest concentrations of 3 tyrosine inhibitors were applied in this experiment. The treating concentrations of Afatinib, Erlotinib, and Sunitinib were 10, 50, and 10 μM, respectively. Data are means±SD from duplicate wells. (B) A representative result of Giemsa stain. The host cell is ARPE-19 cells, and parasites are tachyzoites of T. gondii RH strain.

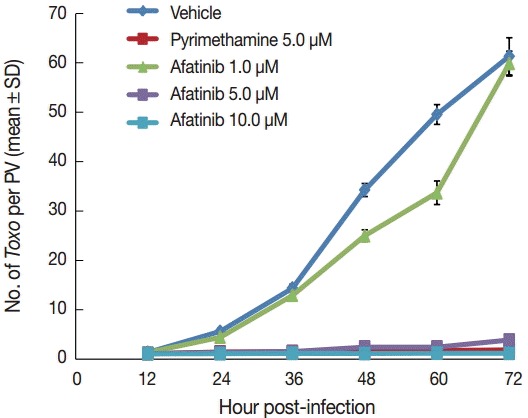

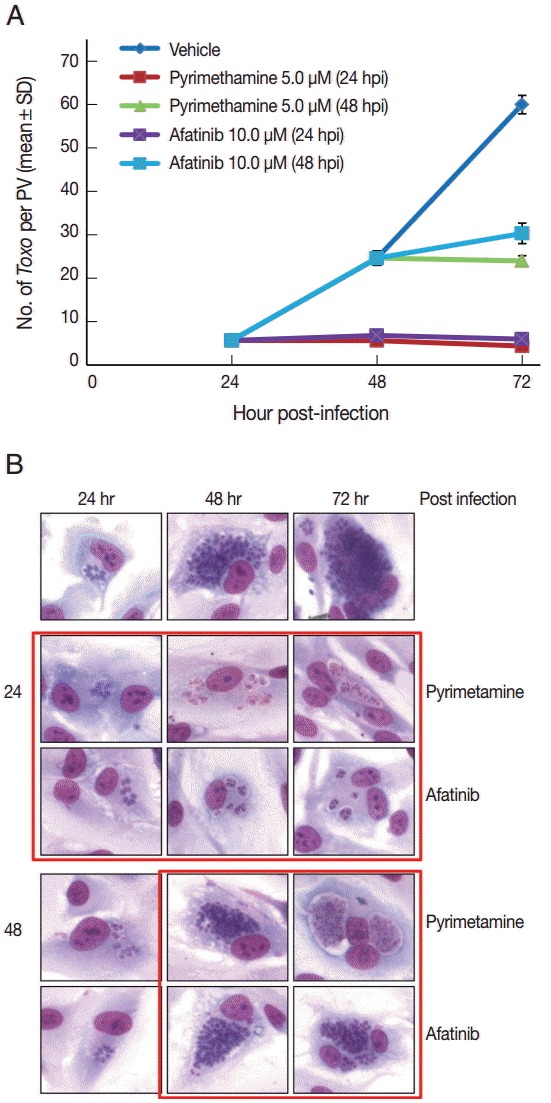

Afatinib 5 µM and 10 µM efficiently inhibited the intracellular growth of T. gondii up to 98.0% equivalent to that of pyrimethamine 5 µM in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2). Fig. 3A shows the changes of the number of parasites per PVM after treatment with Afatinib 10 µM at 24 hr and 48 hr post infection, which shows no more growth of parasites immediately after the treatment of Afatinib, respectively. Fig. 3B shows a representative result of Giemsa stain. These results show that Afatinib 10 µM completely halted the intracellular growth of T. gondii, but did not kill it directly in this experiment.

Fig. 2.

Afatinib inhibits the intracellular growth of the T. gondii RH strain in a dose-dependent manner. The number of parasites was counted per PVM after Giemsa staining after treatment with Afatinib 1, 5, and 10.0 μM concentrations. DMSO was used as the negative vehicle control, whereas pyrimethamine 5.0 μM was used as the positive control.

Fig. 3.

Afatinib halts the growth of T. gondii RH tachyzoites in ARPE-19 cells from the time of treatment. (A) The number of parasites per PVM after treatment with pyrimethamine 5.0 μM and Afatinib 10.0 μM at 24 hr and 48 hr post infection, respectively. DMSO was used as the negative vehicle control. (B) A representative result of Giemsa stain. The host cell is ARPE-19 cells, and parasites are tachyzoites of T. gondii RH strain.

Effect of Afatinib on phosphorylation of STAT6 activated by T. gondii in ARPE-19 cells

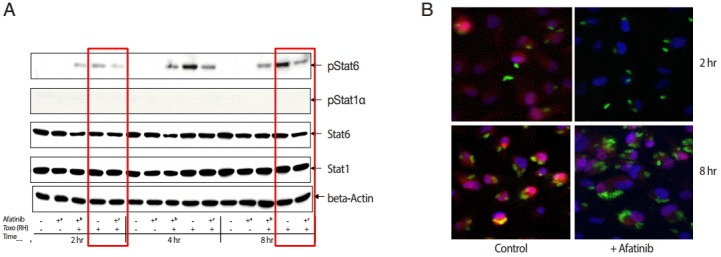

The challenge of T. gondii induced phosphorylation of the Tyr641 site of STAT6, but not the Tyr701 site of STAT1 in ARPE-19 cells (Fig. 4A). The pSTAT6 (Tyr641) peaked at 4 hr post infection. The Afatinib challenge inhibited the phosphorylation of the Tyr641 site of STAT6 activated by T. gondii RH tachyzoites from 2 to 8 hr post infection in ARPE-19 cells. At 2 hr post infection, the group of cells challenged with Afatinib at 1 hr post infection showed stronger inhibition than that before infection. Fig. 4B shows the immunofluorescence stain at 2 hr and 8 hr post infection of which the corresponding results of the western blot in Fig. 4A are marked in red frame. Nuclei of the host cells changed in color more reddish in T. gondii infected cells by the time (Fig. 4B, RH 2 hr and 8 hr, respectively) whereas those of Afatinib treated the red color in the host nuclei was faded out (Fig. 4B, RH-Afatinib 2 hr and 8 hr, respectively). These results showed that Afatinib inhibits the phosphorylation of STAT6 activated by T. gondii in ARPE-19 cells.

Fig. 4.

Afatinib affects the phosphorylation of Stat6 activated by T. gondii (RH) in ARPE-19 cells. (A) The phosphorylation of the Tyr641 site of STAT6, but not the Tyr701 site of STAT1 in the ARPE-19 cells after challenge with T. gondii RH tachyzoites by western blot. The time of Afatinib challenge was the same as T. gondii (RH) infection. Afatinib challenge was at 1 hr before infection and at 1 hr post infection. The concentration of Afatinib was 10 μM, and DMSO was used as the vehicle. (B) Immunofluorescence stain at 2 hr and 8 hr post infection. The corresponding results of the western blot in Fig. 4A are marked in red frame.

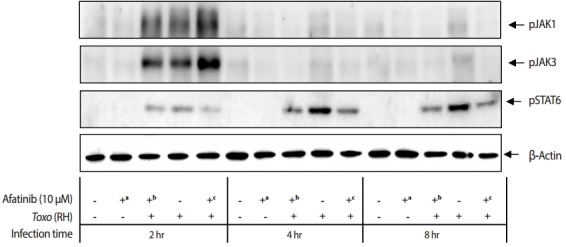

Effect of Afatinib on phosphorylation of JAKs in ARPE-19 cells invaded by T. gondii

The challenge of T. gondii RH tachyzoites induced phosphorylation of the Tyr1022/Tyr1023 sites of JAK1 and Tyr980 site of JAK3 in ARPE-19 cells at 2 hr post infection. However, it is difficult to detect the phosphorylation at 4 hr and 8 hr post infection (Fig. 5). At 2 hr post infection, the group of cells challenged with Afatinib at 1 hr post infection showed higher levels of phosphorylation than that of before infection in the Tyr1022/Tyr1023 sites of JAK1 and the Tyr980 site of JAK3 in ARPE-19 cells. Therefore, the inhibition of the host STAT6 phosphorylation by Afatinib in ARPE-19 cells infected with T. gondii is not due to the host JAK signaling.

Fig. 5.

Effect of Afatinib on the phosphorylation of JAK kinases in ARPE-19 cells invaded by T. gondii RH tachyzoites. The challenge of T. gondii induced phosphorylation of the Tyr1022/Tyr1023 site of JAK1 and the Tyr980 site of JAK3 in the ARPE-19 cells only at 2 hr post infection. The time of Afatinib challenge was the same as compared with T. gondii (RH) infection. Afatinib challenge was at 1 hr before infection and at 1 hr post infection. The concentration of Afatinib was 10 μM, and DMSO was used as the vehicle.

DISCUSSION

The most general treatment for ocular toxoplasmosis is a triple combined therapy, which includes pyrimethamine, sulfonamide, and steroid treatments. However, these therapeutic drugs may induce severe hypersensitivity in sulfa-sensitive patients and bone marrow suppression; these drugs are also ineffective against bradyzoites within tissue cysts [21]. In addition, there have been no effective vaccines available for toxoplasmosis in humans until now. Thus, it is necessary to develop more safe and effective drugs for the treatment of systemic toxoplasmosis, including toxoplasmic encephalitis and toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of several TKIs on the growth of intracellular T. gondii and the relationship with STAT1 and STAT6 phosphorylation in the host ARPE-19 cells.

In this study, we found that some TKIs, Afatinib in particular, inhibited the intracellular multiplication of T. gondii in ARPE cells. Afatinib (5 µM and 10 µM) could efficiently inhibit the intracellular growth of T. gondii which was equivalent to the inhibitory action of pyrimethamine 5 µM in a dose-dependent manner. Afatinib completely halted the intracellular growth of T. gondii at the delayed treatment time as in the pyrimethamine treatment group. Those were regarded as the phenomena found in in vitro culture, which may be removed by immune cells such as cytotoxic T cells or specific phagocytic cells in vivo.

The results of the present study were consistent with an earlier study that kinase inhibitors efficiently blocked the premature egress of T. gondii [22]. The intracellular cycle of T. gondii also depends on host cell factors, and some kinase inhibitors, such as wortmannin, staurosporine, and genistein, which block PI3K, PKC, and tyrosine kinase activities, respectively, have been known to inhibit calcium ionophore A23817-induced invasion and egress at early stages of infection [22-24]. The challenge of T. gondii induced the phosphorylation of the Tyr641 site of STAT6, but not the Tyr701 site of STAT1 in ARPE-19 cells. The pSTAT6 (Tyr641) peaked at 4 hr post infection. The Afatinib challenge inhibited the phosphorylation of the Tyr641 site of STAT6 activated by T. gondii from 2 hr to 8 hr post infection in ARPE-19 cells using western blot and immunofluorescence stain. These results showed that Aafatinib inhibits the phosphorylation of the STAT6 activated by T. gondii RH tachyzoites in ARPE-19 cells. Ahn et al. [25] reported that T. gondii infection can autonomously activate STAT6, and accordingly has induced gene expressions specific to IL-4 responses without IL-4 stimulation.

One study indicated that T. gondii does not activate IL-4 production in the infected individual based on the absence of symptoms, such as asthma or eosinophilia related to IL-4 responses in T. gondii infection [12]. In addition, T. gondii evolves to provoke STAT6 activation in infected cells without an IL-4 stimulus to protect the parasite from the toxoplasmacidal action of IFN-γ/STAT1 pathway. It is suggested that this STAT1/STAT6 cross interaction is a survival strategy of the parasite; therefore, if the cells are infected and STAT6 is activated, the parasite grows normally regardless of the subsequent exposure to IFN-γ [25].

Cytosolic STAT6 is phosphorylated via the IL-4 receptor-associated Janus kinase (JAK) 1 or JAK3 to create a pSTAT6 dimer. JAK1 has been known to respond to many cytokines and mediates the phosphorylation of several STATs, whereas JAK3 restricts IL-4, IL-13 to STAT6, and IL-21 to STAT3 [26,27]. The inhibition of JAK3 blocks STAT6 phosphorylation during the entry and growth of T. gondii in host cells, which suggests the mediation of STAT6 phosphorylation via JAK3 against the direct phosphorylation of STAT6 by a secreted kinase homologue from the ROP 16 [12,28]. In the present study, we demonstrated that the challenge of T. gondii induces the phosphorylation of both the Tyr1022/Tyr1023 site of JAK1 and the Tyr980 site of JAK3 in ARPE-19 cells only at 2 hr post infection and disappears entirely at 4 hr and 8 hr. Therefore, the inhibition of the host STAT6 phosphorylation by Afatinib in ARPE-19 cells infected with T. gondii is not due to the host JAK signaling.

It has been reported that approximately 30% of human proteins may be controlled by protein kinases (PK), which regulate most cellular pathways, especially those involved in signal transduction, and reflects the importance of PKs in cellular processes in eukaryotes [21]. Although some functions and PKIs of T. gondii have been investigated, most PK functions are not fully understood, and thus, how PKs function in signal transduction and which proteins are phosphorylated remain unclear. Previous studies reported that PKs will be promising drug targets for T. gondii because of their essential functions in the life cycle of parasites and the significant sequence differences from mammalian hosts [21,22,24]. Thus, investigators have suggested that PKIs are promising drugs that block a specific step of T. gondii.

Although the exact pathway of inhibition of TKIs remains unclear, especially the role of Afatinib in the intracellular replication of T. gondii in ARPE cells, we suggest that there are some possible mechanisms to describe the effects of Afatinib on the intracellular T. gondii. First, the drug may inhibit host EGFR signal transduction, which may alter the cytoplasmic environment of host cells. Second, PVM may have an EGFR-like molecule. Third, parasites may have internal EGFR-like molecules. Finally, the drug may bind the kinase domain at the C-terminal of some ROPs. However, further investigations are warranted to determine the exact pathway and mechanism of TKIs on the intracellular inhibition of T. gondii. This will also give a hint to develop novel drugs against toxoplasmosis.

In conclusion, some EGFR inhibitors, Afatinib in particular, can play an important role in inhibition of the intracellular replication of T. gondii through inhibition of spontaneous phosphorylation of STAT6 by the parasite.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Basic Science Research Program through National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (no. NRF-2012R1A1A 2002612).

Footnotes

We have no conflict of interest related to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Holland GN. Ocular toxoplasmosis: a global reassessment. Part I: epidemiology and course of disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:973–988. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Subauste CS, Ajzenberg D, Kijlstra A. Review of the series “Disease of the year 2011: toxoplasmosis” pathophysiology of toxoplasmosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2011;19:297–306. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2010.605198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tenter AMA, Heckeroth ARA, Weiss LML. Toxoplasma gondii: from animals to humans. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30:1217–1258. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(00)00124-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCannel CAC, Holland GNG, Helm CJC, Cornell PJ, Winston JV, Rimmer TG. Causes of uveitis in the general practice of ophthalmology. UCLA Community-Based Uveitis Study Group. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:35–46. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holland GN, Lewis KG. An update on current practices in the management of ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:102–114. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01526-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silveira C, Belfort R, Muccioli C, Holland GN, Victora CG, Horta BL, Yu F, Nussenblatt RB. The effect of long-term intermittent trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole treatment on recurrences of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:41–46. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01527-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.John DT, Petri WA. The tissue coccidia: Toxoplasma gondii. Markell and Voge’s Medical Parasitology. 9th ed. St. Louis, Missouri, USA: Sounders, Elsevier; 2006. pp. 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma R, Mathur MN. Stevens-Johnson syndrome following sulfadiazine, Tri-sulfose and sulfatriad therapy. J Assoc Physicians India. 1965;13:727–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carrión-Carrión C, Morales-Suárez-Varela MM, Llopis-González A. Fatal Stevens-Johnson syndrome in an AIDS patient treated with sulfadiazine. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33:379–380. doi: 10.1345/aph.18068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hajj H, Lebrun M, Fourmaux MN, Vial H, Dubremetz JF. Inverted topology of the Toxoplasma gondii ROP5 rhoptry protein provides new insights into the association of the ROP2 protein family with the parasitophorous vacuole membrane. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:54–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hajj H, Demey E, Poncet J, Lebrun M, Wu B, Galéotti N, Fourmaux MN, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Vial H, Labesse G, Dubremetz JF. The ROP2 family of Toxoplasma gondii rhoptry proteins: proteomic and genomic characterization and molecular modeling. Proteomics. 2006;6:5773–5784. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahn HJ, Kim JY, Nam HW. IL-4 independent nuclear translocalization of STAT6 in HeLa cells by entry of Toxoplasma gondii. Korean J Parasitol. 2009;47:117–124. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2009.47.2.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahn HJ, Cho PY, Ahn SK, Kim TS, Chong CK, Hong SJ, Cha SH, Nam HW. Seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis in the residents of Cheorwon-gun, Gangwon-do, Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2012;50:225–227. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2012.50.3.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Yang PL, Gray NS. Targeting cancer with small molecule kinase inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:28–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cruzalegui F. Protein kinases: from targets to anti-cancer drugs. Ann Pharm Fr. 2010;68:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.pharma.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun K, Broms J, Lavander M, Gurram BK, Enquist PA, Andersson CD, Elofsson M, Sjostedt A. Screening for inhibition of the Vibrio cholera VipA-VipB interaction identifies small molecule compounds active against type VI secretion. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4123–4130. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02819-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lepri S, Nannetti G, Muratore G, Cruciani G, Ruzziconi R, Mercorelli B, Palu G, Loregian A, Goracci L. Optimization of small molecule inhibitors of influenza virus polymerase: from thiophene-3-carboxamide to polyamido scaffolds. J Med Chem. 2014;57:4337–4350. doi: 10.1021/jm500300r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qi WX, Shen Z, Lin F, Sun YJ, Min DL, Tang LN, He AN, Yao Y. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of EFGR tyrosine kinase inhibitor monotherapy with standard second-line chemotherapy in previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:5177–5182. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.10.5177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowles DW, Weickhardt A, Jimeno A. Afatinib for the treatment of patients with EGFR-positive non-small cell lung cancer. Drugs Today. 2013;49:523–535. doi: 10.1358/dot.2013.49.9.2016610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dranitsaris G, Schmitz S, Broom RJ. Small molecule targeted therapies for the second-line treatment for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and indirect comparison of safety and efficacy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139:1917–1926. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1510-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei F, Wang W, Liu Q. Protein kinases of Toxoplasma gondii: functions and drug targets. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:2121–2129. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3451-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caldas LA, de Souza W, Attias M. Calcium ionophore-induced egress of Toxoplasma gondii shortly after host cell invasion. Vet Parasitol. 2007;147:210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferreira S, De Carvalho TMU, De Souza W. Protein phosphorylation during the process of interaction of Toxoplasma gondii with host cells. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol. 2003;35:245–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caldas LA, Seabra SH, Attias M, de Souza W. The effect of kinase, actin, myosin and dynamin inhibitors on host cell egress by Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitol Int. 2013;62:475–482. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahn HJ, Kim JY, Ryu KJ, Nam HW. STAT6 activation by Toxoplasma gondii infection induces the expression of Th2 C-C chemokine ligands and B clade serine protease inhibitors in macrophage. Parasitol Res. 2009;105:1445–1453. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1577-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stark GR, Darnell JE., Jr The JAK-STAT pathway at twenty. Immunity. 2012;36:503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiu H, Nicholson SE. Biology and significance of the JAK/STAT signalling pathway. Growth Factors. 2012;30:88–106. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2012.660936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laliberte J, Carruthers VB. Host cell manipulation by the human pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1900–1915. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7556-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]