Abstract

Background

Arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) are the preferred access for hemodialysis (HD) yet they are underutilized. Cannulation of the fistula is a procedure requiring significant skill development and refinement and if not done well can have negative consequences for patients. The nurses' approach, attitude and skill with cannulation impacts greatly on the patient experience. Complications from miscannulation or an inability to needle fistulas can result in the increased use of central venous catheters. Some nurses remain in a state of a ‘perpetual novice’ resulting in a viscous cycle of negative patient consequences (bruising, pain), further influencing patients' decisions not to pursue a fistula or abandon cannulation.

Method

This qualitative study used organizational development theory (appreciative inquiry) and research method to determine what attributes/activities contribute to successful cannulation. This can be applied to interventions to promote change and skill development in staff members who have not advanced their proficiency. Eighteen HD nurses who self-identified with performing successful cannulation participated in audio-recorded interviews. The recordings were transcribed verbatim. The data were analyzed using content analysis.

Results

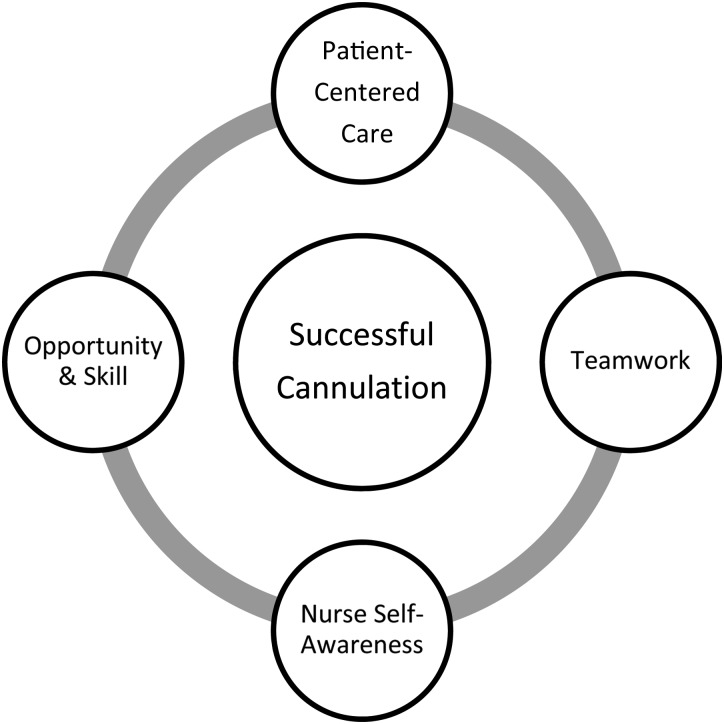

Four common themes, including patient-centered care, teamwork, opportunity and skill and nurse self-awareness, represented successful fistula cannulation. Successful cannulation is more than a learned technique to correctly insert a needle, but rather represents contextual influences and interplay between the practice environment and personal attributes.

Conclusions

Practice changes based on these results may improve cannulation, decrease complications and result in better outcomes for patients. Efforts to nurture positive patient experiences around cannulation may influence patient decision-making regarding fistula use.

Keywords: AV fistula, appreciative inquiry, emotional intelligence, hemodialysis

Introduction

The arteriovenous fistula (AVF) is the preferred vascular access for hemodialysis (HD) and is advocated in clinical practice guidelines [1–4]. Unfortunately, despite much attention and effort by renal organizations to increase fistula rates, many countries fail to meet these evidence-based clinical goals [5–7]. The nurses' approach, attitude and cannulation skill with AVFs have been shown to have an impact on the patient experience with their vascular access [8–12] and on AVF outcomes, including complications following infiltration(s) resulting in the need for a central venous catheter (CVC) [13, 14]. This study addresses an important question: How do you promote change within an HD unit to develop skills for cannulation for optimal vascular access?

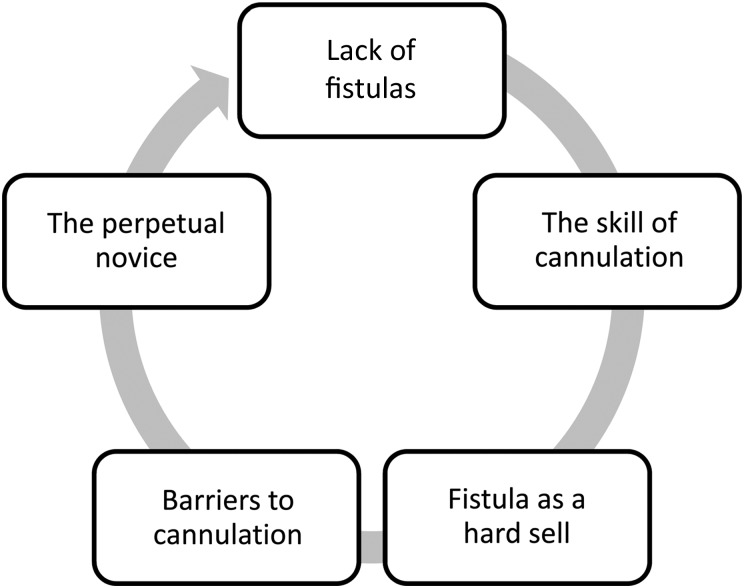

Previous research conducted by the authors of this article have identified that some HD nurses are in a state of ‘perpetual novice’ and are unable to move on a continuum from novice to expert with their cannulation skills for AVFs [11, 12]. This can result in cannulation misses and complications such as increased bruising, pain, fear and, if this persists, a need for insertion or reliance on a CVC. A number of barriers exist in the clinical setting preventing nurses from developing beyond the perpetual novice with cannulation, including the nurse's emotional response, avoidance, patients who refuse certain nurses for cannulation, busy work environments, dialysis schedules and a lack of opportunity to gain experience with the skill [11]. Many patients do not want an AVF if they have observed cannulation problems in their peers such as pain and bruising [10, 12] and delays in dialysis treatments. This further contributes to the problem, creating a vicious cycle: fewer AVFs, less opportunity for skill development, more unsuccessful attempts, fewer patients wanting AVFs and so forth (see Figure 1). Improving outcomes through behavior change appears to be much more complex than providing nursing education on proper needle insertion technique and patient education on the benefits of an AVF.

Fig. 1.

The perpetual novice [11].

We believe that change can occur and the cycle can be broken by developing staff for more successful cannulation. Knowing how HD nurses overcome these barriers and are successful is helpful in identifying the appropriate interventions to develop and maintaining skill competency in cannulation. This study has wide relevance to nephrology, as the results may be applied to interventions that can reduce AVF complications for patients (i.e. bruising, pain) and may assist many renal programs in their efforts to increase AVF rates that meet established evidenced-based practice guidelines to improve patient outcomes.

This study used the method of appreciative inquiry (AI). AI is both an organizational development theory [15] and a research methodology [16] whereby strengths are positively recognized and become the foundation upon which changes are based [17, 18]. Essentially, the method uses positive exemplars to examine what is working and then interventions are implemented based on those attributes.

The purpose of this study was to find attributes of excellence in nursing practice around AVF cannulation that could then be used to cultivate successful interventions to promote changes to patient vascular access outcomes, thus creating a more positive environment/culture for AVFs in the dialysis unit. A qualitative approach will provide data that is rich in description and context, leading to increased understanding.

Method

This study focused on the first two steps of AI by asking the questions ‘What works?’ and ‘What might be?’ [16]. This study was approved by the local research ethics board, and written informed consent was obtained by the research assistant. Purposeful sampling was used whereby investigators sought participants working in three HD units (one free-standing unit, two hospital-based) who had positive experiences with cannulation. The investigators also sought help from the charge nurses to identify nurses they felt had positive experiences with cannulation. Nurses were interviewed once using an interview guide with semi-structured questions. The questions were framed in AI and based on how these nurses overcame barriers to cannulation identified in our previous study that embodies the perpetual novice [12].

The interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and analyzed for common themes using latent content analysis. The sample size was guided by data saturation, at the point where no further themes were arising [19]. Reliability and validity were assessed for qualitative research by using the criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability [20]. The investigators analyzed the data separately and then met as a group to discuss preliminary findings and agree on common themes.

Results

The final sample included 18 nurses. All but one of the participants were female (one no answer) with a mean age of 49 years and an average of 13 years employment in HD, with a mix of part time and full time (see Table 1). Four common themes representing successful cannulation were present in the data: (i) patient-centered care, (ii) opportunity and skills, (iii) teamwork and (iv) nurse self-awareness (see Figure 2). Common themes with supporting quotes are described. Additional quotations are shown in Table 2. Participants are assigned a number for clarity of data presentation, included in parentheses after the quote.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Characteristic | Number of patients (N = 18) | Mean | Range (years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | – | – | |

| Female | 17 | 95% | |

| No answer | 1 | 5% | |

| Age | 49 years | 32–60 | |

| Years employed as a registered nurse | 23 years | 8–37 | |

| Years employed in hemodialysis | 13 years | 1–28 | |

| Employed | |||

| Full time | 10 | 56% | |

| Part time | 8 | 44% | |

Fig. 2.

Themes for successful cannulation.

Table 2.

Patient exemplars supporting the themes

| Theme | Quotation |

|---|---|

| Patient-centered care | ‘I listen to the patient because they know sometimes which way the vessel, they'll say “you know what, if you aim this way … ” and then you start aiming the way they say, I think that's the key—listening to the patient if they are aware of any helpful hints. It is their arm that is being cannulated, you have to use them as a guide if they can help you and then you start making your own assessments too. So, between the two of you, if you are in on it together to get a better outcome.’ (4) ‘I think we really should respect patient wishes, because when the patient is nervous, it doesn't help, it just makes it worse. I think it is just best to get a different nurse that the patient feels comfortable. When the patient is comfortable with the nurse, I think it works better.’ (14) |

| Opportunity and skill | ‘I just think that you keep doing it … and keep doing those assessments. When I help people or assist them, some people they are nervous and they just kind of ram the needle in, I do try to encourage people to take their time, use your fingers and really, really, really get to know that vessel and feel when it goes in. If it goes in and you don't get blood back, pulling back and then feeling the pops in the vessel, you can get to know if you are very slow and methodical. You get to know that, oh it was picked in the bottom of the vessel, or maybe in the side of that vessel because you feel that release. Really, it is taking your time and using the senses that you have.’ (1) ‘Even if you are busy you still have to focus on your patient right? I try, you know, ignore everything that is going on around me and just focus on the patient and stay focused.’ (5) |

| Teamwork | ‘Well, apparently I have been told that I am pretty good at getting some of the difficult patients. I don't hesitate to ask for help. I don't hesitate to get in there and needle new fistulas. Gotta give it a try.’ (3) ‘I am fairly candid with people. I'll say “that's a very shallow fistula, you will go through it and they will bleed”. So I remind them when they are in the assessment when they are feeling the bruit and pulse, just feel it. I mean, if it's just under your fingers you do not have to go deep. I'm candid to people, not in a mean way, in a supportive way. I'll say “that's a shallow fistula”, I mean you can say that, that's not interfering. But it's all in how you do it. If you were nasty but if you say “hey, I've done that person and it's a shallow fistula” and I chart as such too. You don't want the patient to go through unnecessary pain and being turned off. Because I know one of the patients wanted to go back to a central line.’ (17) |

| Nurse self-awareness | ‘So I'm going in and I cause a bruise or I cause a mess. I feel awful for one. But, yeah, if I am confident and I know that I can, that it is really obvious what I did wrong or what went wrong, say the patient moved or jerked or I jerked or made a bad call, um, I will attempt one more time. If I was really confident and then I had a problem, I would call somebody in that I trust. Come and look at this, see what you think and I might do it again after we have assessed, or maybe I'll go get the ultrasound.’ (8) ‘And then, see if they will let me put another needle in because, you know, I do have a personal rule that if I put two needles in and I am not successful, then I pass it on to someone else. There is nothing wrong with admitting you can't get it. I have seen nurses where they go, and you are just “let someone else try”. It's just, you are not having a good day with that person, so I know always to back away. I have had no problems with that, nothing to do with my ego. Because I have had patients say “you are a great needler, can you come back?” So, I know I do a good job, but some days I can't hit the door. That big of a target and it just doesn't really matter so you just back away.’ (4) |

Patient-centered care

Participants described nursing interventions for successful AVF cannulation consistent with patient-centered care. To produce the best patient and nurse outcomes, patients were consistently involved in the cannulation experience, for example … ‘I think just listening to our patients, making them a part of the situation. As I said, it is their arm’ (4). Aspects of this theme commonly reported by participants included acknowledgment of the emotional reaction that AVF cannulation can evoke in the patient, listening and hearing about the patient's experience, education and involving and negotiating with patients regarding their AVF care.

There were many examples of nurses communicating empathy to the patient in regards to the pain and anxiety that can occur with cannulation. The nurses were attuned to the patients' emotional reactions, and if the nurse was nervous they did not want to transfer this to the patient and increase their anxiety. Their ultimate goal was to be successful with the cannulation, and if that meant finding a different nurse to cannulate they did so.

Nurses engaged in patient education on the benefits of AVFs and self-care, anatomy of the fistula, the cannulation procedure and how to manage unfortunate complications such as bruising. Successful cannulation involved … ‘Just preparing the patient properly, making sure they know what I am doing, taking my time and getting everything ready and cannulate them’ (7). Below is an example of involving the patient in the assessment and visualizing their fistula below the skin with ultrasound in order for them to understand why the nurses were cannulating deep:

We do a lot of teaching, we use the ultrasound a lot and we show the patient. See this deep on the ultrasound, that means, so your fistula is this deep and it is good here and then it has a narrowing here. We show them, usually include them … (8).

The nurses sought out patients’ expertise regarding the factor(s) that led to successful cannulation of their AVF in the past. This was not the only way nurses gained knowledge of the access. Participants also described efforts to review the health record and often asked their peers, who had previously been successful with cannulation, for suggestions and/or advice.

Involving patients in their care often resulted in negotiating aspects of their care. The most commonly reported negotiation was who would do the cannulation. Nurses reported there were times patients requested specific nurses to cannulate. This was based on patient concerns, which were acknowledged by nurses to be real or perceived; some were based on past cannulations and others not. At times, the nurse would discuss the issue with the patient and negotiate care, while at other times, the nurse believed having someone else cannulate would put the patient more at ease and diffuse the situation.

If they are like ‘no, no I just can't handle it’, and some people have had really bad, bad attempts on them and they have a difficult fistula or graft. I try to calm the situation. That's how I do it but … if you know with that person there is absolutely no way and they are only going to let certain people cannulate, then you don't waste time, it has been said so many times before, you just say ‘okay I'll do it.’ (8)

Opportunity and skill development

This theme includes aspects of skill development that are important for successful cannulation. First, having opportunities is essential for ‘practicing the skill’ of cannulation, but this was difficult in HD units with limited numbers of AVFs. Performing a thorough assessment is vital for AVF cannulation, and those nurses who are successful at cannulation have an ability to focus on the task at hand regardless of the stimuli in the environment of the dialysis unit. The nurses also engaged in professional development activities related to cannulation.

The nurses frequently commented ‘I think the way to have successful cannulations is to have more fistulas’ (13). They believed that having more accessibility to fistulas meant more opportunity to consolidate their skills and reduce any feelings they had of being nervous with skill performance. Most believed repeatedly cannulating AVFs was essential for their skill development and confidence. The nurses provided examples where staff not comfortable with cannulation of AVFs would avoid cannulation, which further impedes their skill development.

The orientation period was viewed to be a crucial period in which to develop cannulation skills. There were variations in the technique the nurses described for cannulation, but many of them used the technique that they were initially taught. The approach was to practice and do the procedure many times until the nurse was confident in his/her skills.

I think with the orientation that's where it has to start. I think that continuous exposure on a daily basis throughout the six weeks of orientation to cannulations that are, pretty straightforward, just to get you feeling pretty good about that and assessment and taking your time, pulling up a chair, feeling the vessel and that sort of thing is really important (10)

Every nurse in the study described a careful assessment of the fistula prior to cannulation was essential for success. It is best practice and seems rather obvious/basic that a nurse would do an assessment prior to cannulation; however, negative cases were described by participants and are presented below, such as ‘People tend to go in the same spots’ (7), ‘… then we have a lot of people who are timid and so they will just constantly overcannulate in areas or they are afraid to ask for help' (9), and ‘I take my time. I don't just go in there, like, I see some people just go in and they just jab. I take my time, I make sure the person is relaxed and, um, as relaxed as they can be … ’ (8).

In addition to auscultation and inspection of the AVF, the most important component of the assessment was palpation. With palpation of the vessel, they were able to visualize the vessel in their mind and this helped them determine where they needed to cannulate.

I do take pride in doing a full assessment, so I listen to the vessel and I really, really, really depend on my feel. So, I try to visualize the vessel by the way it feels and like visualize that needle going in. (1)

A successful cannulation also involves gathering information from various sources such as the health record, other nurses’ experience and the patients themselves in order to be prepared for the cannulation. The nurses; ‘sort of look back and see if I can tell the history of what's been going on. Talk to the patient as well. Ask them how things have been going with the cannulation …’ (10), and be ‘well prepared before all of my patients come in … make sure I know, read the patient treatment parameters … the specifics of their fistula … and have it all written down in front of me so I know when the patient comes in that I am already mentally prepared for it’ (11).

Participants discussed keeping their skills up to date by attending education sessions, calling experts in vascular access such as the vascular access nurses and watching other nurses cannulate they believed to be expert. Having the opportunity to continually perform the skill was the most common method nurses used to keep their skills current. Only one nurse commented that if she had not cannulated a fistula recently, she would seek out an assignment change or volunteer to cannulate: ‘What I do personally is that I do try to cannulate at least once a day, so I do seek it out’ (18).

The nurses in this study had highly developed skills and were able to focus on the task at hand, making cannulation the priority and setting aside all other issues, concerns or emotions until cannulation was successful.

The one time recently there was just too much going on and so I closed my eyes because I could feel it. I, kind of, zoned out because I was doubting all these people around and I was starting to feel the pressure, and I closed my eyes and just popped the needle in (15).

Teamwork

Teamwork in the dialysis unit and knowing that one can get help from a colleague when necessary is an important factor in successful cannulation. Nurses are sought out who are known to be an ‘expert’ with cannulation for a particular patient or who are considered to be expert regardless of which AVF is being cannulated. There was variation from nurse to nurse in how they assisted their colleagues; some waited to be asked, some volunteered help and some mentored their colleagues. Most of the participants described how they mentored new staff and sought them out, working with them when opportunities for cannulation were available.

Nurse self-awareness

A high degree of self-awareness was noted among participants. They not only were aware of the emotional response that patients have to cannulation but were also aware of their own reactions to cannulation. They approached cannulation with a plan and also established self-rules regarding how many unsuccessful attempts they would allow themselves. The nurses also seemed to be aware of their skill and comfort levels with new and/or difficult fistulas. They expressed the importance of ‘know your limits’ (10).

The skill of cannulation can conjure up emotional reactions within the nurse, which includes an acknowledgement of the pressure of being successful, causing pain to patients and how an unsuccessful attempt affects their confidence with the skill. However, successful cannulation can evoke a strong positive emotional reaction and job satisfaction with the nurse such as:

I just had a couple, three, successful cannulations today and it is exhilarating when you get it, it's kind of a rush actually when you get a successful needle (12)

Participants had awareness of their skills, comfort level and self-rules about how many times they would cannulate a fistula before asking another nurse to try and cannulate. There is a policy in the HD unit with a recommended number of total attempts, however, the nurses followed ‘rules’ that were consistent with their own beliefs about the process.

When it comes to a difficult patient, I usually locate the more experienced staff to come and help. I will start and try to feel and go where I can go and if the patient is starting to feel uncomfortable, I stop. I will only do two at a maximum unless I know for sure that I am going to get the third one in. I never go past three, I always go two and go to somebody who has got more experience or more of an expert (6).

Discussion

Successful AVF cannulation encompasses much more than the technique of needle insertion into a vessel, depending rather on the contextual influences and interplay of the practice environment and the personal attributes of the nurse. The results provide evidence for patient-centered care as an enabler to successful AVF cannulation. The care environment where this study took place emphasizes patient-centered care [21]. A patient and family care advisory committee is in place to create a better understanding of the patient experience and works in collaboration with patients on the planning, delivery and evaluation of renal care. Also in the environment where the study took place is a professional practice model that provides the foundation for how nursing care is delivered and has been documented to benefit nurse and patient outcomes [22, 23]. At the core of the model is patient-centered care [24], which may have impacted the results of this study.

Participants in this study were able to overcome personal and unit barriers to be successful with cannulation. In organizational development terms, when these situations occur, they are positive deviances from the norm and are important for organizational change. The nurses who identify with successful cannulation demonstrated high levels of emotional intelligence (EI). EI is a form of social intelligence that acknowledges the feelings and emotions of others and themselves and uses this information to guide thoughts and actions [25]. EI is an important competency in physician [26, 27] and nurse [28] leadership. There are five main elements of EI: self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy and social skills [29]. The findings of this study include examples of the nurses being aware of their emotions as well as the patient's emotional reaction, such as fear and anxiety. Participants indicated that they are able to self-regulate by doing a thorough assessment, visualizing the fistula, having a plan prior to cannulation and ‘knowing their limits’. They are motivated and expressed an ability to focus on the task despite performing the task in the busy environment of a dialysis unit. The nurses described positive interpersonal relationships with patients (patient-centered care) and nurse-to- nurse teamwork and mentoring. Nurses who have not yet acquired these skills may be able to develop them. The solution may not only be education about the technical aspects of how to cannulate but, rather, emphasis on nurse-to-nurse interpersonal relationships and nurse-to-patient therapeutic relationships that form the foundation for patient-centered care and nurse mentorship, teamwork, EI and giving and receiving feedback. This could be successfully accomplished through the development of clinical narratives in either simulation and/or role playing.

Another barrier to cannulation that the nurses in this study were able to overcome was the pressure of time imposed by HD schedules [11, 12]. This group of nurses completed an assessment prior to cannulation, believing that initial success with needle placement would save time later as a result of miscannulations. This study supports the use of assessment of the fistula as a standard of care, performing one that is thorough, yet not overly time consuming, such as the One-Minute Check [30]. In addition, the use of ultrasound-guided cannulation has been evaluated to add 1–3 min to the time required for cannulation [31].

The nurses in this study received initial training in their orientation period on cannulation. They were first taught the theoretical components of cannulation then they could practice the skill on a simulated practice arm. We have not used high-fidelity patient simulators for cannulation training. Included in this teaching is how to use ultrasound to assist in cannulation, but real-time ultrasound cannulation is not currently taught in the general orientation. Also during orientation, the new nurses observe a cannulation and then cannulate on what would be considered ‘easier’ AV fistulas. Continuing education on cannulation, use of the ultrasound machine and real-time ultrasound cannulation continues ad hoc for professional development. The opportunity to repeatedly perform and practice cannulation was a key factor in the development and maintenance of their skills. If particular units have few fistulas and a large staff, and thus few opportunities for cannulation, efforts are needed to increase the opportunities for cannulation. This could be accomplished by way of simulated cannulation situations or by moving staff within different sites in the organization during orientation and beyond where staff can focus on the skill. Some organizations have chosen to focus on a core group of nurses to do cannulations. This has the advantage of refining the skills for experts. However, others believe cannulation is an essential skill for every HD nurse and thus opportunities for skill development among all staff are required.

Successful cannulation for new or difficult fistulas requires support on a variety of levels: environmental, staff and equipment. Cannulation needs to be planned ahead of time with a quiet environment in the dialysis unit and appropriate equipment available (i.e. bedside ultrasound if available) to enable the nurse to perform a thorough assessment. Support staff such as the vascular access nurse or an expert nurse available to help problem solve and support the bedside nurse during the needling also contributes to successful cannulation.

Use of the ultrasound machine to assist with cannulation in this study was mixed. Some nurses reported it being helpful and some did not. It is recommended at our site that nurses use the ultrasound, however, it is not used consistently, even for first cannulations of the fistula. There is limited research on the use of ultrasound guidance for cannulation of an AVF. However, what is currently available supports the use of ultrasound to improve cannulation [31–34]. A prospective trial is currently under way in an outpatient HD unit [35]. No clinical practice guidelines exist for the use of real-time ultrasound AVF cannulation. The recommendation to use ultrasound guidance for central venous cannulation/insertion has been extrapolated to include real-time use with AVF cannulation [35]. Regardless of the clinical evidence for its use, the harm is minimal and it can be an added tool to help guide the cannulation that may improve patient outcomes. Nurses in this study often said ‘I cannulate how I was taught’. Therefore, it may be prudent to include teaching staff to cannulate with real-time ultrasonography during their orientation as a means to influence how the next generation of people who cannulate AVFs are taught.

This study was undertaken to understand more about what contributes to successful nurse cannulation of the AVF in an effort to identify factors associated with success (Table 3) that can be used to teach other nurses and improve the cannulation experience for patients. Improving this skill could, in turn, break the cycle of the perpetual novice. Interventions that decrease infiltrates, bruising and pain and increase nurse and patient confidence in nurses’ skill will result in more positive patient experiences with AVFs and more positive talk among patients about AVFs. Historically, the constant site needle insertion technique gained acceptance by word of mouth from patients’ positive cannulation experiences [36]. In the long term, this may improve AVF rates and decrease reliance on CVCs for dialysis. Unfortunately, there will always be some degree of fistula problems such as missed cannulations, pain and/or bruising. We need to move beyond the notion that successful cannulation only refers to the insertion of needles and acknowledge that success applies to the entire patient and nurse cannulation experience.

Table 3.

Strategies to promote changes in cannulation

Patient

|

Environment

|

Nurse

|

Conclusion

Organizational development can be used to break the cycle of the perpetual novice in efforts to improve the patients’ cannulation experience for AVFs by focusing on strategies to build support and acknowledge and improve factors such as patient-centered care, teamwork, opportunities for skill development and EI.

Funding

This study was funded by the Canadian Association of Nephrology Nurses and Technologists/Amgen 2014 Canada Research Project Grant.

Conflict of interest statement

The results presented in this article have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract format. The authors do not have any conflict of interests such as shareholding in or receipt of a grant, travel award or consultancy fee from a company whose product features in the submitted manuscript or a company that manufactures a competing product.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Cathy Parsons, Professional Practice Consultant at St Joseph's Health Centre in London, ON, Canada, for her expertise in AI.

References

- 1.Mendelssohn D, Beaulieu M, Kiaii M, et al. Report of the Canadian Society of Nephrology Vascular Access Working Group. Semin Dial 2012; 25: 22–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas A, Appleton D, Browning R, et al. Clinical educators network nursing recommendations for management of vascular access in hemodialysis patients. CANNT J 2006; 16(Suppl 1): 6–17 [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI clinical practice guidelines and clinical practice recommendations for 2006 updates: hemodialysis adequacy, peritoneal dialysis adequacy and vascular access. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48(Suppl 1): S1–S33217045862 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanholder R, Canaud B, Fluck R, et al. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of haemodialysis catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSI): a position statement of European renal best practice (ERBP). Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 3: 234–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CIHI. CORR Annual Report: Treatment of End-Stage Organ Failure in Canada 2002–2012. Toronto: Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 6.USRDS. United States Renal Data System 2014 Annual Report. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes, Digestion and Kidney Disease, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noordzj R, Jager KJ, van der Veer SN, et al. Use of vascular access for haemodialysis in Europe: a report from the ERA-EDTA registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014; 29: 1956–1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Axley B, Rosenblum A. Learning why patients with central venous catheters resist permanent access placement. Nephrol Nurs J 2012; 39: 99–103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richards C, Engebreston J. Negotiating living with an arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis. Nephrol Nurs J 2010; 37: 363–374 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xi W, Harwood L, Diamant MJ, et al. Patient attitudes toward the arteriovenous fistula: a qualitative study on venous vascular access decision making. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26: 3302–3308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson B, Harwood L, Oudshoorn A, et al. The culture of vascular access cannulation among nurses in a chronic hemodialysis unit. CANNT J 2010; 20: 35–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson B, Harwood L, Oudshoorn A. Moving beyond the ‘perpetual novice’. Understanding the experience of novice hemodialysis nurses and cannulation of the arteriovenous fistula. CANNT J 2013; 23: 11–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee T, Barker J, Allon M. Needle infiltration of arteriovenous fistulae in hemodialysis: risk factors and consequences. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48: 1020–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Loon M, van der Sande FM, Tordoir JH. Cannulation practice patterns in hemodialysis vascular access: predictors for unsuccessful cannulation. J Ren Care 2009; 35: 82–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooperrider D, Srivastva S. Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. In: Woodman R, Pasmore W. (eds). Research in Organizational Change and Development. Greenwich, CT, USA: JAI Press, 1987, pp. 129–169 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter B. One expertise among many-working appreciatively to make miracles instead of finding problems. Using appreciative inquiry as a way of reframing research. J Res Nurs 2006; 11: 48–63 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haven D, Woods J, Leeman J. Improving nursing practice and patient care. Building capacity with appreciative inquiry. J Nurs Adm 2006; 36: 463–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoon M, Lowe M, Budgell M, et al. An exploratory investigation using appreciative inquiry to promote nursing oral care. Geriatr Nurs 2011; 32: 326–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayan M. Essential of qualitative inquiry. In: Morse J. (eds). Qualitative Essentials. Walnut Creek, CA, USA: Left Coast Press, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA, USA: Sage, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 21.IPFCC. Patient and Family Centre Care. 2015. http://www.ipfcc.org (24 July 2015, date last accessed)

- 22.Harwood L, Ridley J, Lawrence-Murphy JA, et al. Nurses perception of the impact of a renal nursing professional practice model on nursing outcomes, characteristics of practice environments and empowerment. Part I. CANNT J 2007; 17: 22–29 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harwood L, Ridley J, Lawrence-Murphy JA, et al. Nurses perception of the impact of a renal nursing practice model on nursing outcomes, characteristics of practice environments and empowerment. Part II. CANNT J 2007; 17: 35–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harwood L, Ridley J, Downing L. The renal nursing professional practice model: the next generation. CANNT J 2013; 23: 14–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salovey P, Mayer J. Emotional intelligence. Imagin Cogn Pers 1990; 9: 185–211 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hammerly M, Harmon L, Schwaitzberg S. Good to great: using 360 degree feedback to improve physician EI. J Healthc Manag 2014; 59: 354–364 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mintz L, Stoller J. A systematic review of physician leadership and emotional intelligence. J Grad Med Educ 2014; 6: 21–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parnell R, St Onge J. Teaching safety in nursing practice: is emotional intelligence a vital component? Teach Learn Nurs 2015; 10: 88–92 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goleman D. Emotional Intelligence: Why it can Matter More Than IQ. New York, NY, USA: Bantum Books, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 30.End-Stage Renal Disease National Coordinating Center. It only takes a minute to save your patient's lifeline. Arteriovenous Fistula. First AVF—The First Choice for Hemodialysis 2015. http://www.esrdncc.org (10 December 2015, date last accessed)

- 31.Paulson W, Brouwer-Maier D, Pryor L, et al. Early experience with a novel device for ultrasound-guided management and cannulation of hemodialysis vascular access. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 26: 288A [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adams B, Soi V, Yee J, et al. Hand held ultrasound device solves vascular access (VA) cannulation problems. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 26: 293A [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carneiro F, Ramos A, Barbeiro B, et al. Reducing adverse effects of arteriovenous fistula cannulation with Doppler ultrasound. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014; 26: 889A [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marticorena R, Kumar L, Dhilon G, et al. Real-time imaging of vascular access to optimize cannulation practice and education: role of the access procedure station. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014; 26: 889A [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel R, Stern AS, Brown M, et al. Beside ultrasonography for arteriovenous fistula cannulation. Semin Dial 2015; 28: 433–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Twardowski Z. Update on cannulation techniques. J Vasc Access 2015; 16(Suppl 9): S54–S60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]