Abstract

In the United States trauma is the leading cause of mortality among those under the age of 45, claiming approximately 192,000 lives each year. Significant personal disability, lost productivity and long term healthcare needs are common and contribute 580 billion dollars in economic impact each year. Improving resuscitation strategies and the early acute care of trauma patients has the potential to reduce the pathological sequelae of combined exuberant inflammation and immune suppression that can co-exist, or occur temporally, and adversely affect outcomes. The endothelial and epithelial glycocalyx has emerged as an important participant in both inflammation and immunomodulation. Constituents of the glycocalyx have been used as biomarkers of injury severity and have the potential to be target(s) for therapeutic interventions aimed at immune modulation. In this review, we provide a contemporary understanding of the physiologic structure and function of the glycocalyx and its role in traumatic injury with a particular emphasis on lung injury.

Keywords: Endothelium, epithelium, glycocalyx, glypican, heparan sulfates, inflammation, pneumonia, syndecan, trauma, wounds

1. Introduction

The goal of this review is to provide state of the art knowledge on the composition and function of the glycocalyx present on both endothelial and epithelial cells as they relate to the pathophysiology of trauma. In the first half of this review, we will present an accumulating body of evidence suggesting that immediate post-traumatic plasma concentrations of glycocalyx constituents are a reasonable measure of injury severity and clinical outcome and may contribute to trauma-induced coagulopathy. We assume that trauma-induced increases in plasma concentration of glycocalyx elements are derived from shedding of the vascular endothelial surface and thus, we feel it is important to provide the appropriate historical and scientific background about the lung endothelial glycocalyx. In the latter half of this review, we turn our attention to the glycocalyx present on epithelial cells and review the literature regarding its role in the host response to pneumonia. Glycocalyx constituents expressed on lung epithelial cells appear to play an important role in modulating the host response to bacterial infection and resolution of inflammatory processes.

In the global context of both normal physiology and trauma injuries, the endothelial glycocalyx plays an important role in vascular permeability(1) by limiting protein and solvent flux into the cell junction; it regulates leukocyte and platelet interaction with adhesion cell molecules on the endothelial surface(2) thus influencing the local inflammatory cascade and the heparan sulfate component modulates the local cell surface coagulation system.(3) Trauma-induced activation of neutrophil-derived proteases and tissue-derived MMPs results in cleavage and loss of cell surface HSPG, exposing ICAM and selectins that promotes leukocyte and platelet adhesion to the endothelium(4-6); this adhesion induces further release of cytokines, proteases and heparanase that worsens glycocalyx degradation, causes endothelial cell contraction(7) and, in total, increases permeability. The glycocalyx also participates in oxidative signaling induced by mechano-transduction(8) that, in turn, influences both barrier regulation and immune-cell adhesion in response to acute changes in blood pressure and flow(1; 9) that occur during hemorrhagic shock. Importantly, shed proteoglycan ectodomains, and free HS chains function as a Danger-Associated Pattern Molecule (DAMP) that activate TLR-2 and -4(10) and HS are co-factor(s) for HMBG1 in order to bind to and activate RAGE.(11; 12) The soluble HS chains likely contribute to auto-heparinization that is part of the coagulopathy of trauma.(13; 14) Hyaluronan fragments, released from the glycocalyx during acute inflammation, are also DAMPS that can activate TLR-dependent pathways. In the broad scheme of trauma, components from the glycocalyx contribute to the propagation of sterile inflammation but, concurrently, also contribute to immunosuppression via TLR-dependent processes.(15) These two factors likely explain why plasma concentrations of syndecan-1 are so highly correlated with the severity of injury and outcomes following trauma(16; 17) and why trauma patients are prone to nosocomial pneumonias such a Pseudomonas pneumonia.(18) Indeed, shed syndecan-1 ectodomains are associated with greater levels of inflammation and P. aeruginosa infection in mice while syndecan-1 null mice were protected from P. aeruginosa-induced lung injury. Conversely, the administration of isolated syndecan-1 ectodomains or free heparan GAG chains, in combination with P. aeruginosa, abolished the protective phenotype of the syndecan-1 KO mice(9) and created a more severe pneumonia. Collectively, the intact glycocalyx plays a homeostatic role in maintaining normal permeability, an anti-inflammatory and anti-coagulative vessel wall. Trauma-induced inflammation and subsequent breakdown of the glycocalyx promotes a pro-inflammatory(19) and immunosuppressive state that likely leads to worse outcomes for trauma patients. These topics will be discussed in greater detail below.

2. Structure and Function of the Glycocalyx

Structure

The glycocalyx composition varies according to the tissue and cell type, but it is composed primarily of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) and proteoglycans (PG). The main GAGs are heparan sulfates, chondroitin sulfates and hyaluronan. Heparan sulfates and chondroitin sulfates are carried by PG that belong to two main families: syndecans and glypicans. While syndecans may carry both heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate, glypicans only carry heparan sulfate.(20; 21) Hyaluronan is a large secreted GAG that remains in association with the endothelial surface and is thought to be a major structural component of the glycocalyx(22) (Figure 1).

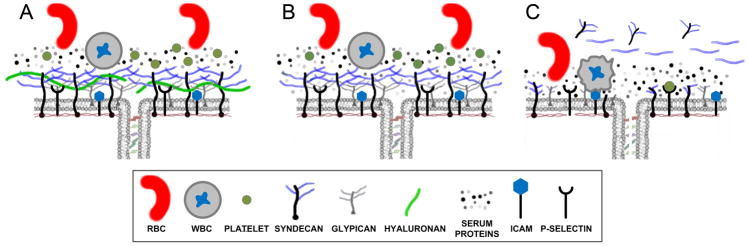

Figure 1.

A) An intact endothelial glycocalyx provides a barrier between the plasma compartment and the cell membrane and limits RBC, WBC and platelets from contacting the cell surface. The glycocalyx and associated immobile protein layer overlies the cell junction contributing to endothelial barrier properties for both water and protein flux. B) During mild to moderate inflammation, shedding and proteolytic cleavage of the glycocalyx (in this case removal of hyaluronan) increases the porosity of the glycocalyx. C) During severe inflammation and trauma, breakdown of the glycocalyx exposes ICAM and P-selectin resulting in increased WBC and platelet adhesion, respectively, and propagation of the inflammatory response. Note the presence of shed syndecans and heparan sulfates in the plasma that are hypothesized to contribute to auto-heparinization and the coagulopathy of trauma (see text for detail).

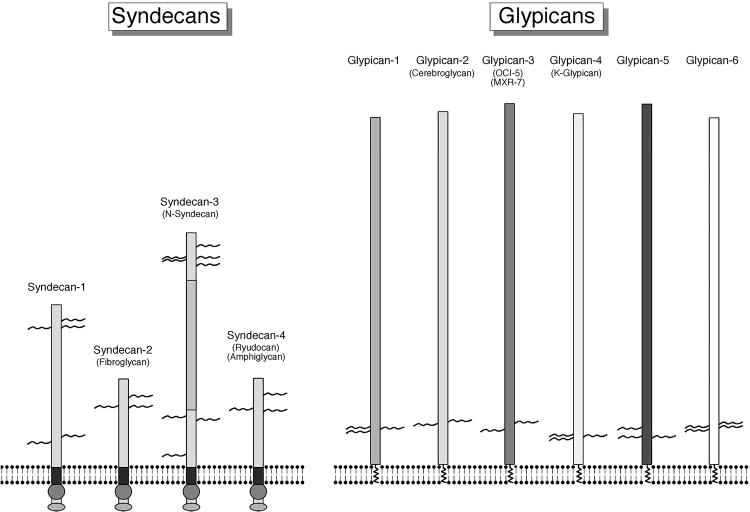

Syndecans are among the best studied components of the glycocalyx with respect to trauma. The syndecan family is comprised of 4 members (syndecan 1-4) with isoforms 1, 2 and 4 being expressed by most cell types, while syndecan-3 expression is limited to neuronally-derived cells(23) (Figure 2). Syndecans are unique as they are a transmembrane proteoglycan with a large extracellular domain and a highly conserved cytoplasmic domain. GAGs are covalently attached to the extracellular domain at a conserved GXXXG motif. The cytoplasmic domain (c-domain) contains a variable sequence unique to each isoform and two conserved sequences common to all syndecans. The c-domain contains a PDZ domain, several phosphorylation sites and binds several unique proteins that link syndecan to the cytoskeleton and other signaling molecules. The functions of the glycocalyx are incompletely understood and most of the published data about proteoglycan function in the lung are focused on syndecans. Thus, this review will focus on syndecan regulation of lung cell functions. The syndecan family is currently known to be involved in biological processes such as wound healing, inflammation, neural patterning, angiogenesis(24; 25) and regulation of endothelial mechanotransduction.(19; 26; 27)

Figure 2. Structure of Syndecans and glypicans.

The generalized structure of syndecan 1-4 (left panel) and glypicans 1-6 (right panel) are shown for comparison. The primary structural features to note are that syndecans have a transmembrane region and a highly conserved cytoplasm domain that participates in signaling. Syndecan can carry both heparan sulfate GAGs and chondroitin sulfate GAG. Glypicans contain a larger core protein, insert into the membrane via a GPI anchor and only carry heparan sulfate GAGs. Modified from: CE. Bandtlow and Dieter R. Zimmermann Physiol Rev 2000;80:1267-1290

In mammals, the glypican family is comprised of 6 members (glypican 1-6),(20) but little is known about isoform-specific functions. Glypicans are bound to the cell membrane by a glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor located within a hydrophobic domain close to the C-terminus.(28) The GAG binding sites for heparan sulfates are conserved across the glypican family and are located in proximity to the carboxyl terminal and thus close to the cell membrane suggesting the heparan chains could mediate the interaction of glypicans with other cell surface molecules(20) (Figure 2).

Function

In a historical context, the glycocalyx was considered to be a simple physical barrier that acted as a filter over the endothelial cell junction and that influenced water flux and solute filtration. This idea was derived from early electron microscopy that showed a dense layer on the endothelial surface overlying cell-cell junctions(29). The first evidence for a role of the endothelial glycocalyx (EG) on barrier regulation dates to work by Mason, et al., in the late 1970's, who described the endocapillary layer as a three-dimensional network that was strengthened by the absorption of plasma proteins(30). The EG regulates vascular permeability in two ways: by creating a passive filter over cell-cell junctions(31-33) and by acting as a signaling platform that actively regulates junctional integrity. Regarding the glycocalyx as a molecular filter, it creates a passive permeability barrier by forming a polymer scaffolding on the vascular wall that serum proteins absorb onto and into. This absorbed plasma layer has been called “the immobile plasma layer” and, based on its viscosity, is presumed to be an important component of the permeability barrier. The glycocalyx, per se, meaning the proteoglycans, cell-surface glycans and the immobile plasma layer are best referred to as the “endothelial surface layer”(33) (Figure 1).

The endothelial glycocalyx is localized between flowing blood and the cell membrane and is perfectly positioned to regulate permeability via mechanotransduction.(1; 34) The literature suggests that heparan sulfates are capable of sensing hydrostatic pressure and fluid shear stress that, in turn, activates nitric oxide (NO) production.(31; 35) Heparinase and hyaluronidase treatment blocks shear stress-induced NO production as well as the associated increased hydraulic conductance suggesting that heparan sulfates and hyaluronan participate in flow sensing. Chondroitinase only partially inhibited the shear stress-induced increase in hydraulic conductance suggesting a lesser role for this GAG in mechanosensing and barrier function. NO production is also regulated by local actin filaments(36) providing a conceptual framework linking mechanotransduction with cell surface components via actin. It has been reported that endothelial glycocalyx components can participate in cytoskeletal organization and rearrangement during shear stress and the subsequent activation of downstream pathways that influence permeability. Syndecans, for instance, are linked to cytoskeletal elements including actin via their cytoplasmic domains (37) and have been proposed to be a principle effector in mechanotransduction although glypican-1 has been directly linked to shear stress-dependent NO production. (27) Recent investigations have shown that pressure-induced vascular permeability changes may be sensed by the glycocalyx and transduced by ion channels and other signaling pathways. For example, Kuebler and Bhattacharya were the first to report the activation of pressure-dependent, calcium-sensitive signaling pathways in the lung. Circumferential stretch of pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells, in response to increased microvascular perfusion pressures and/or alveolar ventilation pressures, induces NO production(38) presumably via calcium-dependent activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). Increases in hydrostatic pressure also cause rapid translocation of P-selectin to the endothelial cell surface(39) leading to increased leukocyte margination(40) and propagation of inflammatory events within the lung vessels. Thus, the glycocalyx participates in mechanosensing and mechanotransduction that propagates the inflammatory cascade as reviewed below.

3. Glycocalyx and Trauma

3.1. Animal studies

In many pathologic conditions, alterations in vascular permeability are, in part, caused by breakdown of the glycocalyx. Studies of enzymatic degradation of the glycocalyx, coupled with direct measures of fluid filtration have shown that an intact glycocalyx contributes upwards of 60% of the resistance to fluid filtration across the capillary wall.(41; 42) Degradation of the glycocalyx in various organs results in similar findings. For example, perfusion of myocardial capillaries with hyaluronidase caused nearly complete loss of the glycocalyx and resulted in significant myocardial edema.(43) Heparinase and pronase were also used to demonstrate the role of the coronary glycocalyx in arteriolar permeability. In isolated perfused arterioles from porcine hearts, both heparinase and pronase increased the apparent solute permeability coefficient (Ps) to albumin and lactalbumin, demonstrating a significant role of the glycocalyx in limiting solute flux.(44) Likewise, perfusion of mouse lungs with heparinase causes significant interstitial edema and increases in pulmonary artery pressure.(45)

Inflammation-induced degradation and shedding of the glycocalyx from mesenteric post-capillary venules of rats subjected to hemorrhagic shock was demonstrated by electron microscopy,(46) while the shock-dependent decrease in venular glycocalyx thickness (by 59%) was quantified by intra-vital microscopy.(47) This latter in vivo data indicates that the glycocalyx of mesenteric and post-capillary muscle venules are shed following hemorrhagic shock, suggesting that hemorrhagic shock causes widespread damage to the glycocalyx. The glycocalyx is important in rheology and vascular resistance as demonstrated by various studies that measured the relationship between blood flow and glycocalyx removal(48-50) induced by enzymatic and pharmacological degradation. For example, vascular resistance was shown to decrease significantly after enzymatic degradation of the glycocalyx with heparinase.(51) A meta-analysis of 28 clinical studies was used to derive systemic resistance during hemodilution, and reported that the use of protein-free fluids for volume expansion led to a decrease in peripheral resistance that was independent of viscosity. The decrease in resistance beyond the magnitude that can be accounted for by viscosity is in agreement with the effect of a 1.5 micron thick endothelial surface layer on blood flow resistance. The results were consistent with the hypothesis that hemodilution of plasma components led to a dynamic loss of plasma proteins from the glycocalyx and resulted in an increase in permeability.(52) Similar effects on resistance were observed in vivo by Torres, et al., who demonstrated this phenomenon after hemorrhagic shock.(53) The microvasculature of a cremasteric muscle preparation was evaluated, before and after hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation, and blow flow and shear rates were derived. The authors reported that Hextend (HEX) improved blood flow and shear rates and FFP improved blood flow and preservation of coagulation status.(53) Their results support the idea that plasma proteins and exogenous colloids influence the structure and thickness of the glycocalyx and endothelial surface layer and, in turn, the thickness of the glycocalyx alters vascular resistance. Protection and or restoration of the glycocalyx after hemorrhagic shock would, therefore, have clinical relevance for maintenance of perfusion pressure and endothelial barrier function.

Therapeutic Options

In a rat model of inflammation, doxycycline (a broad spectrum metalloprotease inhibitor) treatment stabilized the glycan components of the endothelial glycocalyx by inhibiting matrix metalloproteases (MMP), which in turn reduced leukocyte and endothelial cell adhesion in post-capillary venules.(4) These and other studies by Lipowsky and colleagues demonstrate the role of MMPs in glycocalyx shedding and the requirement of glycocalyx degradation for leukocyte binding to endothelial surface adhesion molecules.(2; 54)

Chappell, et al., demonstrated that protection of the glycocalyx by hydrocortisone and anti-thrombin reduced post-ischemic neutrophil adhesion and, in turn, this reduced the degree of vascular leakage, tissue edema and inflammation.(55) Ischemia-reperfusion is also associated with increased platelet adhesion to the coronary vasculature and is associated with a 20-fold increase in heparan sulfate and 9-fold increase in syndecan-1 concentration in the effluent. Pretreatment with hydrocortisone reduced platelet adhesion by 40% and reduced syndecan-1 shedding by approximately 6-fold.(56) Other important strategies for protecting the glycocalyx have been investigated by Becker and colleagues and reviewed in Becker BF, et al.(57) Clinically relevant agents that can reduce shedding and protect the glycocalyx include hydrocortisone,(58) anti-thrombin(59) and sevoflurane.(49)

In a coagulopathic mouse model of trauma and hemorrhagic shock, endothelial permeability in pulmonary vasculature was corrected with fresh frozen plasma (FFP) administration and this was related to restoration of syndecan-1 expression in the pulmonary vasculature.(60; 61) Taken together, these preclinical studies demonstrate an important role for the glycocalyx in controlling vascular permeability and indicate that agents that restore the glycocalyx layer may protect against pathologic increase in vascular permeability. These animal models highlight the importance of protecting and restoring the endothelial glycocalyx before and during vascular injury. The implementation of such strategies is considered promising in the critical care setting and has been addressed by several investigators.(2; 57) The impact of glycocalyx restoration on the outcome from trauma injuries requires further validation and will certainly be the subject of future investigations.

3.2. Human Studies

Numerous studies of trauma patients have been conducted to assess the correlation of plasma concentrations of glycocalyx constituents with trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC) (Table 1). In an observational study by Johansson, et al., on 80 adult trauma patients, of whom 91% experienced blunt trauma and 31% had severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), 15% of the patients had acute coagulopathy of trauma, also called TIC.(62) In this report, patients with TIC were found to have higher injury severity scores (ISS), transfusion requirements and mortality. Additionally, biomarkers pointing to endothelial glycocalyx damage were found in higher levels among patients with TIC(62) which included increased levels of syndecan-1 in the TIC group. Increasing injury severity was shown to be associated with evidence of glycocalyx degradation, coagulation factor consumption, and hyperfibrinolysis.(63) Furthermore, Ostrowski and Johansson, in their retrospective analysis of 77 trauma patients, found that patients with signs of auto-heparinization as determined by thromboelastography had four-fold higher plasma syndecan-1 levels. Thus, they concluded that glycocalyx degradation may induce endogenous heparinization in trauma patients with severe injury.(13) However, the degradation of the endothelial glycocalyx seems to be associated with TIC suggesting that it could be a compensatory response to shock, to overcome the effects of endothelial activation, which results in increased procoagulant activities on the surface of microvessels.(64)

Table 1. Trauma and Glycocalyx: Clinical Studies.

| Study Design | No. Subjects | Ref | Year | Study Population | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective Study | 18 | 50 | 2007 | Patients undergoing aortic surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass and circulatory arrest | Plasma syndecan and heparan sulfate increased 42- and 10-fold, respectively, following reperfusion after circulatory arrest. Syndecan and HS increased 65- and 19-fold, respectively, after CPB. |

| Prospective Observational Study | 32 | 61 | 2011 | Trauma patients in hemorrhagic shock | Significantly elevated levels of plasma syndecan-1 following injury; levels decreased with resuscitation but still elevated compared to control samples. Pro-inflammatory cytokines (interferon-γ, fractalkine, and interleukin-1β,) negatively correlated with syn-1; IL-10 positively correlated with plasma levels of syndecan-1. |

| Prospective Cohort Study | 75 | 65 | 2011 | Trauma patients admitted to a Level 1 trauma Centre in 2003-2005 | Examined 17 markers for glycocalyx degradation. Patients with high plasma syndecan-1 had higher catecholamines, IL-6, IL-10, histone-complexed DNA fragments, HMGB1, thrombomodulin, D-dimer, tPA, uPA and 3-fold increased mortality despite comparable ISS. Syndecan-1 was an independent predictor of mortality (OR: 1.01 [95%CI, 1.00-1.02]; P = 0.043) when adjusted for ISS. |

| Prospective Observational Study | 80 | 62 | 2011 | Adult, Level 1 trauma patients | Patients with high circulating syndecan-1 had higher catecholamines, IL-6, IL-10, histone-complexed DNA fragments, HMGB1, thrombomodulin, D-dimer, tPA, uPA and 3-fold increased mortality (42% vs. 14%) despite comparable ISS. After adjusting for age and ISS, syndecan-1 was an independent predictor of mortality. |

| Prospective Observational Study | 80 | 68 | 2012 | Adult Level 1 trauma patients, | Older trauma patients had higher noradrenaline compared to younger patients. Older trauma patients had low anti-thrombin, high activated protein C, protein S, and tissue factor pathway inhibitor and hyperfibrinolysis (high tissue-type plasminogen activator). Age was an independent predictor of mortality after adjusting for ISS, pre-hospital GCS, and plasma catecholamines. |

| Prospective Observation Study | 77 | 13 | 2012 | Level 1 trauma | Four patients (5.2%) displayed evidence of high-degree auto-heparinization and had higher ISS. They had lower hemoglobin levels and received more transfusions during the first 1 hour Patients with auto-heparinization had four-fold higher syndecan 1 levels and they had higher INR, thrombomodulin and interleukin 6 but lower protein C. |

| Prospective Study | 75 | 66 | 2012 | Level 1 adult trauma Patients Admitted Directly from the scene or accident | Adrenaline levels were higher in non-survivors were independently associated with increased activated partial thromboplastin time and syndecan-1. Syn-1 correlated with biomarkers of tissue and endothelial damage (histone-complexed DNA, high-mobility group box 1, soluble thrombomodulin) and hyperfibrinolysis. Non-survivors had higher syndecan-1, tissue factor pathway inhibitor, and D-dimer. Plasma adrenaline was independently associated with 30-day mortality. |

| Prospective Observational Study | 80 | 67 | 2012 | Level 1 trauma patients | High plasma sCD40L was associated with markers for tissue and endothelial damage (ISS, hcDNA, Annexin V, syndecan-1 and sTM), shock (pH, standard base excess), sympathoadrenal activation (adrenaline) and coagulopathy, evidenced by reduced thrombin generation, hyperfibrinolysis (D-dimer), increased activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) and inflammation (IL-6). High circulating high age and low Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) pre-hospital were independent predictors of increased mortality. |

| Prospective Observational Study | 80 | 68 | 2012 | Level 1 trauma patients | Plasma sVEGFR1 correlated with injury severity (ISS), shock, tissue injury, and inflammation (IL-6). sVEGFR1 correlated with biomarkers indicative of endothelial glycocalyx degradation including syndecan-1, sTM, Ang-2 and hyperfibrinolysis (tPA; D-dimer) and with activated protein C. High plasma sVEGFR1 correlated with both early and late transfusion requirements but was not associated with mortality. |

Among the 17 markers of glycocalyx degradation and endothelial damage, high circulating syndecan-1 were found to be associated with coagulopathy and increased mortality despite comparable ISS in a prospective cohort of 75 trauma patients (10 patients with a penetrating injury and 24 patients with a severe head injury). In patients with high glycocalyx degradation levels, higher ISS was correlated with higher adrenaline, IL-6, histone-complexed DNA fragments, high mobility group box-1, thrombomodulin, activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and lower plasma protein C. After adjusting for age and ISS, syndecan-1 was found as an independent predictor of mortality among trauma patients with varying severities.(65) In a study of 32 severely injured patients experiencing hemorrhagic shock, syndecan-1 levels were noted to be significantly elevated.(61) Syndecan-1 levels were positively correlated with interleukin-10 and inversely correlated with interferon-γ, fractalkine and interleukin-1β.(61) Furthermore, in a prospective study evaluating the association between sympatho-adrenal activation and coagulopathy in 75 adult trauma patients, 14% of whom had penetrating trauma and 33% had TBI, plasma adrenaline levels were higher among non-survivors and the increased trauma-induced catecholamine surge was independently associated with higher syndecan-1 levels, indicative of glycocalyx degradation. Non-survivors had higher syndecan-1 levels compared to survivors, in parallel with the former finding of higher epinephrine levels.(66) In addition to epinephrine, other markers have been shown to increase in correlation with endothelial and glycocalyx injury following trauma, including CD40-ligand (sCD40L). Positive correlations between sCD40L and biomarkers such as soluble thrombomodulin and syndecan-1, representing endothelial damage and glycocalyx degradation, respectively, were demonstrated after trauma.(67) Additionally, high sCD40L was correlated with prolonged aPTT, decreased thrombin generation and hyperfibrinolysis, as indicated by higher D-dimer levels.(67) Similarly, in a study of 80 trauma patients, soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1, which has anti-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory functions and is primarily expressed by endothelial cells, was positively correlated with injury severity scores and plasma syndecan-1 levels, supporting the idea that plasma levels reflect endothelial glycocalyx degradation.(68) In summary, these human clinical trials demonstrate that plasma syndecan-1 is a useful biomarker for severity of injury and it correlates with outcome following traumatic injuries. Despite the results of these clinical studies, the mechanisms causing the degradation of the endothelial glycocalyx after severe trauma in humans are poorly understood. Additional studies are needed to better understand the pathophysiology of the degradation and possibility for reconstitution of the endothelial glycocalyx after severe trauma and hemorrhagic shock.

4. Glycocalyx and Lung Injury

4.1 Trauma as a risk factor for bacterial pneumonia

Trauma represents the leading cause of death for adults under the age of 45 years, and results in extensive morbidity and healthcare costs.(69) Beyond the primary injuries suffered as a result of trauma, nosocomial complications including bacterial pneumonia represent a major complication for trauma patients and evidence suggests that trauma itself is an independent risk factor for the development of pneumonia. In fact, intubated trauma patients have a higher incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) compared to non-trauma patients.(18) Identifying the immunologic basis for this increased susceptibility to bacterial pneumonia should lead to improved care models to reduce both the incidence and subsequent morbidity.

The incidence of VAP varies from center to center but a general average is approximately 15-30%(70; 71) for intubated trauma patients. Most cases of VAP, for all categories of intubated patients, are caused by Enterobacter species (33%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (33%) or Staphylococcus aureus (20%).(72) Despite the development and widespread use of the “ventilator bundle” (stress ulcer prophylaxis, elevated head of bed, deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis and daily sedation interruption) there is little evidence to indicate that these interventions alter the incidence of trauma VAP. An assessment of risk factors for developing VAP among trauma patients identifies male gender, age, chest trauma, multiple rib fractures and severity of injury as the leading indicators.(70) Since these risk factors cannot be controlled, new care models must be developed to characterize and treat the underlying pathophysiology that leads to pneumonia in this group of patients.

As the United States enters an unprecedented stage of an aging population, with nearly 10,000 people turning age 65 every day, the incidence of traumatic injury in this group will increase and their associated co-morbidities will have a differential effect on survival among these older patients. A review of trauma outcomes for 1621 patients, who were older than 50 years of age, at a single trauma center, suggests that a history of coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, rib fractures and a requirement for intubation were associated with increased mortality. Gender, obesity, lung disease, renal failure and cirrhosis were not associated with increased mortality in this single center study.(73) Older trauma patients do not seem to have a higher incidence for VAP unless they also incur traumatic brain injury, in which case age, ISS and coma upon admission are independent risk factors for late-onset VAP (occurring on or after day 5 post admission).(74)

4.2 The epithelial glycocalyx in pneumonia and lung inflammation

Within the lung, the alveolar epithelial glycocalyx has emerged as an important participant in modulating inflammation, infection and allergic processes within the airway compartment. As such, understanding the role of the epithelial glycocalyx and how its components modulate the pathogenesis of alveolar inflammation and localized infection offers a new area for the development of novel therapeutic agents (Table 2).

Table 2. Trauma and Glycocalyx: Preclinical Studies.

| Reference | Year | Strain, Animal (Rat, Mouse) | Model | Model of Injury/Infectious Agent | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80 | 2009 | C57BL/6 and c57BL/6JTicam (TRIF mutant) MyD88 knockout (MyD88−/−) Mouse | Syn-1 KO | Staphylococcus aureus (Intra-nasal) | wild-types mouse had increased histological grade of lung injury, increased BAL albumin, increased BAL cell count following SA pneumonia, relative to syn-1−/−. Syn-1−/− appears protective. |

| 81 | 2010 | C57BL/6 WT TNFR1 KO Mouse | Intra-nasal ADAM10/17 inhibitor | TNFa/IFN administered in isolated perfused lung prep | ADA17 inhibitors reduced syn-1 shedding |

| 82 | 2012 | C57BL/6J Mouse | Syn-4−/− | Intra-tracheal LPS, BAL neutrophils, chemokines, protein | 1. syn-4−/− had increased neutrophil infiltration and worsened lung injury 2. purified syn-4 ectodomains and heparin attenuated inflammatory response in syn-4KO |

| 85 | 2002 | C57BL/6 WT Mouse | CD44−/− | Escherichia coli | neutrophil infiltration, histological lung injury |

| 86 | 2007 | C57BL/6J Mouse | CD44−/− | Intra-tracheal LPS | CD44−/− mice had increased severity of inflammation and lung injury |

| 87 | 2010 | C57BL/6 Mouse | CD44−/− | Klebsiella pneumoniae Intra-nasal | bacterial gorwth and dissemination, neutrophil infiltration, histological lung injury, HA content, cytokine levels, CD44−/− had no effect on survival but had prolonged inflammation, lower levels of resiltion, less bacterial dissemination. CD44 participates in resolution of K.pneumoniae |

| 83 | 2002 | Mouse C57BL/6 | matrilysin−/− | Bleomycin Induced lung injury | mAT−/− had reduced syn-1 shedding; matrilysin induced syn-1 shedding establishes a chemokine gradient that regulated neutrophil migration. |

Bacterial pneumonia represents one of the most common causes of pulmonary failure seen after severe trauma and, therefore, warrants considerable attention. Rodent models of pneumonia closely mimic human acute lung injury and have become some of the better models for studying lung inflammation.(75) These models have advantages over systemic injury models like cecal ligation and puncture.(76; 77) Instillation of pathogenic bacteria into the nares or trachea of anesthetized mice results in a severe but survivable pneumonia and allows both the development and resolution/repair phases to be studied in relationship to alterations of the glycocalyx structure and its functional role in epithelial biology.

Very little is known about the composition and organization of the respiratory epithelial glycocalyx. A recent review(78) nicely details the organization of the mucin layer found in the upper tracheobronchial tree in association with goblet cells and ciliated epithelium and begins to characterize the location of glycans on the epithelial surface. The mucin layer produced by goblet cells that covers the ciliated epithelium can be functionally stratified into the thick mucus layer and the peri-cellular mucus layer. The former is thicker and more viscous while the later is less viscous. The specific mucin content of each layer is distinctly different and likely represents a further extension of functional stratification at the molecular scale. The primary GAGs are associated with the epithelial cell surface and, specifically, with the cilia are keratin sulfates. The presence of a thick mucus layer above ciliated epithelial cells obscures the role of cell-surface glycans, so we depend on future studies to help elucidate the functions of peri-cellular GAG and the ciliated epithelial glycocalyx.

The associated acute lung injury that occurs in severe forms of pneumonia increases capillary permeability at the alveolar level. Therefore, it makes sense to focus on the glycocalyx from the type I epithelial cells that comprise approximately 95% of the alveolar surface area and form one-half of the air-blood interface. Numerous studies focused on the role of syndecan-1 and -4 in mouse models of bacterial pneumonia have assessed syndecan shedding into the distal air space of the lungs. As it will be reviewed below, syndecans may participate in inflammation by signaling via the cytoplasmic domain as well as functional attributes of the GAG chains.(23; 79) The preponderance of published data has been focused on syndecan-1 and -4; hence, this review of the glycocalyx and pneumonia is centered on these two isoforms.

4.3 Syndecans and Bacterial Pneumonia

Mice inoculated intra-nasally with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) develop a severe pneumonia with significant lung injury(9). However, syndecan-1 knockout (KO) mice demonstrate a protective phenotype, with reduced histological evidence of inflammation, less lung and spleen colonization of bacteria and improved survival. When exogenous syndecan-1 ectodomains were administered with P. aeruginosa to the lungs of syndecan-1 KO mice, the protective effect was mitigated and inflammation, injury and mortality were comparable to wild type (WT) mice. Therefore, the protective effect of the syndecan-1 KO appears to be due to loss of the ectodomain, which carries the GAG chains. To test the role of heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate in the pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa, heparin and chondroitin sulfate GAGs were administered in combination with the bacteria to syndecan-1 KO mice. Again, the protective phenotype was lost. Finally, studies assessing whether P. aeruginosa binds heparan sulfates to avoid detection were performed and the results suggested that direct physical interaction is not necessary for the enhanced virulence. Collectively, these results suggest that syndecan-1 and heparan sulfates enhance the virulence of P. aeruginosa by altering the response of the innate immune system and not via direct action on the bacteria itself. Similar results were observed in Staphyloccocus aureus (S. aureus) pneumonia in mice. Syndecan-1 KO mice revealed significantly reduced lung inflammation in terms of histology, BAL fluid cell count and albumin concentration.(80) S. aureus releases a β-toxin that is a neutral sphingomyelinase that induces shedding of syndecan-1 ectodomain off the surface of airway epithelial cells. The β-toxin-induced shedding of syndecan-1 increases the virulence of S. aureus pneumonia that seems to be related to increased neutrophil recruitment and cytokine production. In the absence of syndecan-1, inflammation is reduced. Taken together, these results indicate that the shedding of syndecan-1 is increasing the virulence of lung bacterial infections, although additional studies are needed to better understand the mechanisms of this increased bacterial virulence caused by shed syndecan-1 and the heparan sulfate GAG chains.

Syndecan-4 is a prominent member of the syndecan family that is expressed by endothelial and epithelial cells. Both syndecan-1 and -4 are shed from epithelial cells to the bronchoalveolar fluid during lung inflammation in vitro when lung epithelial cells are exposed to phorbol myristate acetate, thrombin, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) or interferon-gamma.(81) When syn-4 KO mice are challenged with intra-tracheal LPS, they manifest worse injury as assessed by increased neutrophil influx and increased CXCL8 production than wild-type littermates.(82) Purified syn-4 ectodomains and exogenous heparin attenuated the inflammatory response to LPS and TNF-α. Thus, syn-4 is protective against LPS-induced lung inflammation and the heparan side chains contribute most of this protective activity.

The glycocalyx may also modulate the progress of inflammation and pneumonia by indirect mechanisms. Epithelial and endothelial barrier injuries are both commonly observed in lung injury. The lung epithelium and immune cells can release chemokines driving the influx of inflammatory cells through the epithelial layer. Syndecan-1 can indirectly regulate inflammation by modulation of this chemotatic gradient. In a bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis model, matrylisin cleaves syndecan, which has keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC), a murine functional homolog of interleukin-8, bound to the GAG chains; KC is involved in directing neutrophil migration from the interstitial space to the alveolar compartment. In matrilysin-null mice that have significantly reduced syndec-1 shedding, neutrophil migration was limited to the interstitium. Moreover, KC was not detected in the alveolar fluid of syndecan-1 KO mice. These results describe a fundamental protective role of syndecan-1 in the epithelial response to injury. However, the lack of syndecan could lead to impaired resolution of epithelial injury and worsening inflammation.(83)

4.4 Hyaluronan and Bacterial Pneumonia

Finally, we will examine the effect of epithelial hyaluronic acid (HA) on models of infectious lung injury. HA is a large secreted GAG that remains associated with the cell surface. Epithelial cells and a variety of hematopoetic-derived cells including macrophages express CD44, a binding protein for HA. CD44 is a multi-functional signaling protein that plays an important role in modulating the inflammatory response of macrophages. In its native state, high molecular weight (MW) HA has anti-inflammatory properties. Subjects diagnosed with chronic bronchitis, who presented with recurrent exacerbation of their disease, and that were treated with inhaled HA for six months had decreased acute bronchitis exacerbations compared to subjects that were treated with placebo. Accordingly, HA-treated subjects presented with fewer signs of bacterial infection and reduced need for antibiotic treatment. These results suggest that HA may enhance host-defense mechanisms.(84)

High MW HA is susceptible to cleavage via hyaluronidase, an enzyme present in endothelial, epithelial and white blood cells. Low MW HA fragments are pro-inflammatory, presumably by interacting with CD44, although the mechanism(s) for this action remain obscure. CD44 KO mice provide significant insight into the role of CD44 and HA during infectious inflammation in the lung. CD44 KO mice express prolonged and exaggerated inflammation following bleomycin-induced lung injury(85) and infectious processes. For example, CD44 KO mice develop significantly worse lung inflammation in response to Escherichia coli(85), LPS,(86) and Klebsiella pneumonia.(87) Taken together, high MW epithelial HA appears to attenuate inflammation by binding to macrophage CD44 while small HA fragments are pro-inflammatory, although the mechanisms explaining the increase in airway inflammation by these small HA fragments are not fully understood.(88)

4.5 Glycocalyx and other Mechanisms of Lung Injury

Apart from bacterial pneumonia, glycocalyx proteins can also be important in secondary respiratory failure in critically ill adults. Schmidt and collaborators have shown that different etiologies of lung inflammation may modulate glycocalyx degradation. Data collected from healthy donors or subjects with respiratory failure secondary to: 1) intoxication or ischemic brain injury (patients were mechanically ventilated); 2) indirect lung injury (non-pulmonary sepsis or pancreatitis) and 3) direct lung injury (pneumonia or aspiration) showed that circulating heparan sulfate fragments and heparanase activity were elevated in patients with indirect lung injury, while circulating HA concentrations were elevated in all groups but with statistical difference only in the direct lung injury group. Plasma heparan sulfate concentrations directly correlated with intensive care unit length of stay. Although this study was performed with a small group of subjects, it raises the need for additional large studies on glycocalyx degradation in respiratory failure due to lung inflammation (direct or indirect).(89)

Breakdown products resulting from proteolytic cleavage of the glycocalyx can induce further inflammation as well as inducing an immunosuppressive state. For example, heparan sulfate and hyaluronan fragments are DAMPs that can activate TLR2 and TLR4 receptors that induce further inflammation (10), while heparan fragments a are a co-factor for HMBG1 and it's binding to RAGE.(11; 12) The conditions that determine the coordinated response of RAGE, TLR2, and TLR4 activation to exacerbate inflammation and/or induce neutrophil and T-cell immunosuppression remain poorly understood and will crucial to furthering our understanding of the glycocalyx in trauma-related injuries.

In summary, the tracheobronchial epithelial glycocalyx in coordination with secreted mucins are an important barrier component to imped and/or prevent pathogens from gaining access to the epithelial cell. In the alveolar compartment, heparan sulfate GAGs on syndecan-1 and -4 appear to be important regulators of the innate immune response and can either enhance or attenuate the inflammatory response to specific pathogens. At our early stages of understanding, it is clear that much more work is required to unify the dichotomous findings regarding the functional significance of the glycocalyx in bacterial pneumonia.

5. Glycocalyx shedding and lung inflammation

The endothelial glycocalyx varies in thickness from 0.5μm to several microns(90; 91) depending on the vascular bed, species and type of endothelial cell being studied. Given these dimensions, an intact glycocalyx would extend well above endothelial cell adhesion molecules present on the cell surface. During acute inflammation, shedding of the glycocalyx may be part of the controlled immune response to improve neutrophil and platelet binding and recruitment to the site of injury. Mulivor and colleagues presented the early evidence that anti-intracellular adhesion molecule (anti-ICAM) antibody (ab)-coated beads had minimal binding to the endothelial surface of mesenteric vessels. Following stimulation with formyl-methionine-leucine-phenylalanine (fMLP), these investigators observed increased binding of ab-coated beads to the vascular wall, which was associated with reduced lectin binding to the endothelium. Perfusion of the vessels with heparinase produced nearly identical results(92) validating the idea that loss of cell surface glycans is associated with increased accessibility of the bead with anti-ICAM. In similar studies, Mulivor and colleagues assessed the influence of fMLP and ischemia on binding of anti-syndecan ab-coated beads and lectins to the endothelial surface. Ischemia and fMLP resulted in reduced lectin binding, consistent with loss of cell surface glycans. However, they observed increased binding of anti-syndecan coated beads, reflecting an increased accessibility of the beads with the syndecan core protein. Collectively, these results suggest that, in this model, the syndecan core protein is retained at a time when the GAG chains are lost.(5) Thus, the heparan chains provided the structural barrier that limited access of ab-coated beads to ICAM. Inhibition of vessel wall MMP attenuated the shedding of endothelial glycans and reduced the amount of leukocyte binding induced by fMLP.(4)

The glycocalyx prevents neutrophil adhesion to microvascular endothelial cells in the lung, but during sepsis and acute lung injury loss of the glycocalyx allows neutrophil adhesion. Using a mouse model of endotoxemia, Schmidt and colleagues demonstrated a rapid breakdown of the glycocalyx and concurrent increase in neutrophil binding to vessel wall.(6) Endotoxemia resulted in a TNF-dependent increase in heparanase activity that was responsible for the early glycocalyx breakdown; treatment with heparanase inhibitor mitigated the breakdown of the glycocalyx and associated neutrophil binding. This well performed study validates the role of the endothelial glycocalyx in maintaining minimal leukocyte-endothelial interactions during basal states and the necessity for regulated shedding of glycans that allow leukocyte binding to the endothelium.

6. Future Directions

Much more work is needed to further our understanding of the role of glycocalyx on both endothelial and epithelial cells. The spatial localization on the cellular scale and three-dimensional organization of the glycocalyx represent important structural information yet to be described. Tarbell and colleagues have begun these descriptive studies using confocal imaging of endothelial cells in vitro(93) and they have been developing techniques to perform similar studies in vivo.(94) Biophysical techniques like fluorescence correlation spectroscopy have been used to determine three dimensional organization and protein dynamics within the interior of the glycocalyx.(22) Higher resolution imaging that will allow more precise localization of individual components and improved methods for fixation that preserve the in vivo structure will aid in answering many important structure-function questions. Preliminary steps quantify the biomechanical characteristics of the glycocalyx, in vitro, that are important for mechanosensing have been made using reflectance interference contrast microscopy and atomic force microscopy.(95) Adapting these techniques for use in vivo remains an unmet technical challenge but one that is sure to provide important comparisons of the in vitro vs. in vivo glycocalyx.

At the level of whole animal studies, virtually all published data from KO animals, examining the glycocalyx in lung injury, are derived from global KO mice and not from tissue-specific KO and/or inducible KOs that can be timed in order to assess the acute response, resolution and recovery from injury. Without cell-specific KOs, it is impossible to precisely determine which cell types are affected by the knocked-out protein and which cells play a dominant role in a specific response. For example, most syndecan KO mice showed reduced neutrophilic infiltrate; was this effect a result of syndecan KO on endothelial or epithelial cells or neutrophils? In what cell type is the loss of syndecan most important for modulating sterile inflammation and/or bacterial infection? What is the effect of trauma and subsequent on endothelial and/or epithelial glycocalyx?

There is no doubt that components of the glycocalyx will continue to be identified as major players in the regulation of inflammation and in the resolution and recovery phases, as well. As we understand more about cell-specific functions of syndecans and other proteoglycans, we can envision therapeutic interventions based on their role in mechanism-specific inflammation. The development of novel, glycocalyx-targeted polymers could represent a major advance for both protection of the glycocalyx from proteolytic degradation and restoration of the glycocalyx following shedding. Giantsos, et al.,(96) and Giantsos-Adams, et al.,(97) have demonstrated a proof-of-concept for developing glycocalyx-targeted polymers that enhance barrier properties, attenuate inflammation and attenuate pressure-dependent mechanotransduction. The authors synthesized a 50-60kD water-soluble polymer (methacyrlamidopropyl trimethylammonium chloride) that bound avidly to the endothelial surface and was devoid of any measurable in vitro toxicity. The polymer reduced endothelial hydraulic conductivity, reduced the pressure-dependent production of nitric oxide and mitigated pressure-dependent and shear-dependent barrier failure. Lastly, the polymer was able to block bradykinin-induced increase in endothelial albumin permeability. The development of similar functionalized polymers for human use would represent a significant advance in resuscitation science. In conclusion, much more work is needed to develop therapies directed to exploit the multi-functional glycocalyx.

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: NIH RO1 GM086416 (JFP) and the UAB Kirklin Grant (RTR)

References

- 1.Collins SR, Blank RS, Deatherage LS, Dull RO. Special article: The endothelial glycocalyx: Emerging concepts in pulmonary edema and acute lung injury. Anesth Analg. 2013;117(3):664–74. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182975b85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipowsky HH. The endothelial glycocalyx as a barrier to leukocyte adhesion and its mediation by extracellular proteases. Ann Biomed Eng. 2012;40(4):840–8. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0427-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pries A, Kuebler W. Normal endothelium. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2006;176:1–40. doi: 10.1007/3-540-32967-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulivor AW, Lipowsky HH. Inhibition of glycan shedding and leukocyte-endothelial adhesion in postcapillary venules by suppression of matrix metalloprotease activity with doxycycline. Microcirculation. 2009;16(8):657–66. doi: 10.3109/10739680903133714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulivor AW, Lipowsky HH. Inflammation- and ischemia-induced shedding of venular glycocalyx. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286(5):H1672–80. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00832.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt EP, Yang Y, Janssen WJ, Gandjeva A, Perez MJ, Barthel L, Zemans RL, Bowman JC, Koyanagi DE, Yunt ZX, Smith LP, Cheng SS, Overdier KH, Thompson KR, Geraci MW, Douglas IS, Pearse DB, Tuder RM. The pulmonary endothelial glycocalyx regulates neutrophil adhesion and lung injury during experimental sepsis. Nat Med. 2012;18(8):1217–23. doi: 10.1038/nm.2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dudek SM, Garcia JG. Cytoskeletal regulation of pulmonary vascular permeability. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2001;91(4):1487–500. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.4.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dull RO, Cluff M, Kingston J, Hill D, Chen H, Hoehne S, Malleske DT, Kaur R. Lung heparan sulfates modulate k(fc) during increased vascular pressure: Evidence for glycocalyx-mediated mechanotransduction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302(9):L816–28. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00080.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park PW, Pier GB, Hinkes MT, Bernfield M. Exploitation of syndecan-1 shedding by pseudomonas aeruginosa enhances virulence. Nature. 2001;411(6833):98–102. doi: 10.1038/35075100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson GB, Brunn GJ, Kodaira Y, Platt JL. Receptor-mediated monitoring of tissue well-being via detection of soluble heparan sulfate by toll-like receptor 4. J Immunol. 2002;168(10):5233–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu D, Young J, Song D, Esko JD. Heparan sulfate is essential for high mobility group protein 1 (hmgb1) signaling by the receptor for advanced glycation end products (rage) J Biol Chem. 2011;286(48):41736–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.299685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu D, Young JH, Krahn JM, Song D, Corbett KD, Chazin WJ, Pedersen LC, Esko JD. Stable rage-heparan sulfate complexes are essential for signal transduction. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8(7):1611–20. doi: 10.1021/cb4001553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostrowski SR, Johansson PI. Endothelial glycocalyx degradation induces endogenous heparinization in patients with severe injury and early traumatic coagulopathy. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(1):60–6. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31825b5c10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pierce A, Pittet JF. Inflammatory response to trauma: Implications for coagulation and resuscitation. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2014;27(2):246–52. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darwiche SS, Ruan X, Hoffman MK, Zettel KR, Tracy AP, Schroeder LM, Cai C, Hoffman RA, Scott MJ, Pape HC, Billiar TR. Selective roles for toll-like receptors 2, 4, and 9 in systemic inflammation and immune dysfunction following peripheral tissue injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(6):1454–61. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182905ed2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johansson P, Stensballe J, Rasmussen L, Ostrowski S. A high admission syndecan-1 level, a marker of endothelial glycocalyx degradation, is associated with inflammation, protein c depletion, fibrinolysis, and increased mortality in trauma patients. Ann Surg. 2011;254:194–200. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318226113d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahbar E, Cardenas JC, Baimukanova G, Usadi B, Bruhn R, Pati S, Ostrowski SR, Johansson PI, Holcomb JB, Wade CE. Endothelial glycocalyx shedding and vascular permeability in severely injured trauma patients. J Transl Med. 2015;13:117. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0481-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards JR, Peterson KD, Andrus ML, Tolson JS, Goulding JS, Dudeck MA, Mincey RB, Pollock DA, Horan TC, Facilities N. National healthcare safety network (nhsn) report, data summary for 2006, issued june 2007. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(5):290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voyvodic PL, Min D, Liu R, Williams E, Chitalia V, Dunn AK, Baker AB. Loss of syndecan-1 induces a pro-inflammatory phenotype in endothelial cells with a dysregulated response to atheroprotective flow. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(14):9547–59. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.541573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Filmus J, Capurro M, Rast J. Glypicans. Genome Biol. 2008;9(5):224. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-5-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartlett AH, Hayashida K, Park PW. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of syndecans in tissue injury and inflammation. Mol Cells. 2007;24(2):153–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevens AP, Hlady V, Dull RO. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy can probe albumin dynamics inside lung endothelial glycocalyx. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293(2):L328–35. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00390.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi Y, Chung H, Jung H, Couchman JR, Oh ES. Syndecans as cell surface receptors: Unique structure equates with functional diversity. Matrix Biol. 2011;30(2):93–9. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan MR, Humphries MJ, Bass MD. Synergistic control of cell adhesion by integrins and syndecans. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(12):957–69. doi: 10.1038/nrm2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alexopoulou AN, Multhaupt HA, Couchman JR. Syndecans in wound healing, inflammation and vascular biology. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39(3):505–28. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Annecke T, Fischer J, Hartmann H, Tschoep J, Rehm M, Conzen P, Sommerhoff CP, Becker BF. Shedding of the coronary endothelial glycocalyx: Effects of hypoxia/reoxygenation vs ischaemia/reperfusion. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107(5):679–86. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ebong EE, Lopez-Quintero SV, Rizzo V, Spray DC, Tarbell JM. Shear-induced endothelial NOs activation and remodeling via heparan sulfate, glypican-1, and syndecan-1. Integr Biol (Camb) 2014;6(3):338–47. doi: 10.1039/c3ib40199e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Filmus J, Selleck SB. Glypicans: Proteoglycans with a surprise. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(4):497–501. doi: 10.1172/JCI13712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clough G. Relationship between microvascular permeability and ultrastructure. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1991;55(1):47–69. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(91)90011-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mason JC, Curry FE, Michel CC. The effects of proteins upon the filtration coefficient of individually perfused frog mesenteric capillaries. Microvasc Res. 1977;13(2):185–202. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(77)90084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dull RO, Mecham I, McJames S. Heparan sulfates mediate pressure-induced increase in lung endothelial hydraulic conductivity via nitric oxide/reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292(6):L1452–8. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00376.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curry FE, Adamson RH. Endothelial glycocalyx: Permeability barrier and mechanosensor. Ann Biomed Eng. 2012;40(4):828–39. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0429-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pries AR, Secomb TW, Gaehtgens P. The endothelial surface layer. Pflugers Arch. 2000;440(5):653–66. doi: 10.1007/s004240000307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tarbell JM, Ebong EE. The endothelial glycocalyx: A mechano-sensor and -transducer. Sci Signal. 2008;1(40):pt8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.140pt8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Florian JA, Kosky JR, Ainslie K, Pang Z, Dull RO, Tarbell JM. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a mechanosensor on endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2003;93(10):e136–42. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000101744.47866.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zharikov SI, Sigova AA, Chen S, Bubb MR, Block ER. Cytoskeletal regulation of the l-arginine/no pathway in pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280(3):L465–73. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.3.L465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chakravarti R, Sapountzi V, Adams JC. Functional role of syndecan-1 cytoplasmic v region in lamellipodial spreading, actin bundling, and cell migration. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(8):3678–91. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuebler WM, Uhlig U, Goldmann T, Schael G, Kerem A, Exner K, Martin C, Vollmer E, Uhlig S. Stretch activates nitric oxide production in pulmonary vascular endothelial cells in situ. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(11):1391–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-562OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ichimura H, Parthasarathi K, Quadri S, Issekutz AC, Bhattacharya J. Mechano-oxidative coupling by mitochondria induces proinflammatory responses in lung venular capillaries. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(5):691–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI17271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ichimura H, Parthasarathi K, Issekutz AC, Bhattacharya J. Pressure-induced leukocyte margination in lung postcapillary venules. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289(3):L407–12. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00048.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adamson RH. Permeability of frog mesenteric capillaries after partial pronase digestion of the endothelial glycocalyx. J Physiol. 1990;428:1–13. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curry FR, Adamson RH. Vascular permeability modulation at the cell, microvessel, or whole organ level: Towards closing gaps in our knowledge. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87(2):218–29. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van den Berg BM, Vink H, Spaan JA. The endothelial glycocalyx protects against myocardial edema. Circ Res. 2003;92(6):592–4. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000065917.53950.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huxley VH, Williams DA. Role of a glycocalyx on coronary arteriole permeability to proteins: Evidence from enzyme treatments. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278(4):H1177–85. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strunden MS, Bornscheuer A, Schuster A, Kiefmann R, Goetz AE, Heckel K. Glycocalyx degradation causes microvascular perfusion failure in the ex vivo perfused mouse lung: Hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4 pretreatment attenuates this response. Shock. 2012;38(5):559–66. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31826f2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kozar RA, Peng Z, Zhang R, Holcomb JB, Pati S, Park P, Ko TC, Paredes A. Plasma restoration of endothelial glycocalyx in a rodent model of hemorrhagic shock. Anesth Analg. 2011;112(6):1289–95. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318210385c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Torres Filho I, Torres LN, Sondeen JL, Polykratis IA, Dubick MA. In vivo evaluation of venular glycocalyx during hemorrhagic shock in rats using intravital microscopy. Microvasc Res. 2013;85:128–33. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Becker BF, Fischer J, Hartmann H, Chen CC, Sommerhoff CP, Tschoep J, Conzen PC, Annecke T. Inosine, not adenosine, initiates endothelial glycocalyx degradation in cardiac ischemia and hypoxia. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2011;30(12):1161–7. doi: 10.1080/15257770.2011.605089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chappell D, Heindl B, Jacob M, Annecke T, Chen C, Rehm M, Conzen P, Becker BF. Sevoflurane reduces leukocyte and platelet adhesion after ischemia-reperfusion by protecting the endothelial glycocalyx. Anesthesiology. 2011;115(3):483–91. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182289988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rehm M, Bruegger D, Christ F, Conzen P, Thiel M, Jacob M, Chappell D, Stoeckelhuber M, Welsch U, Reichart B, Peter K, Becker BF. Shedding of the endothelial glycocalyx in patients undergoing major vascular surgery with global and regional ischemia. Circulation. 2007;116(17):1896–906. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.684852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pries AR, Secomb TW, Jacobs H, Sperandio M, Osterloh K, Gaehtgens P. Microvascular blood flow resistance: Role of endothelial surface layer. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(5 Pt 2):H2272–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.5.H2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pries AR, Secomb TW, Sperandio M, Gaehtgens P. Blood flow resistance during hemodilution: Effect of plasma composition. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;37(1):225–35. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torres LN, Sondeen JL, Ji L, Dubick MA, Torres Filho I. Evaluation of resuscitation fluids on endothelial glycocalyx, venular blood flow, and coagulation function after hemorrhagic shock in rats. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75(5):759–66. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182a92514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Constantinescu AA, Vink H, Spaan JA. Endothelial cell glycocalyx modulates immobilization of leukocytes at the endothelial surface. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(9):1541–7. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000085630.24353.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chappell D, Dorfler N, Jacob M, Rehm M, Welsch U, Conzen P, Becker BF. Glycocalyx protection reduces leukocyte adhesion after ischemia/reperfusion. Shock. 2010;34(2):133–9. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181cdc363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chappell D, Brettner F, Doerfler N, Jacob M, Rehm M, Bruegger D, Conzen P, Jacob B, Becker BF. Protection of glycocalyx decreases platelet adhesion after ischaemia/reperfusion: An animal study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2014;31(9):474–81. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Becker BF, Chappell D, Bruegger D, Annecke T, Jacob M. Therapeutic strategies targeting the endothelial glycocalyx: Acute deficits, but great potential. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87(2):300–10. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chappell D, Jacob M, Hofmann-Kiefer K, Bruegger D, Rehm M, Conzen P, Welsch U, Becker BF. Hydrocortisone preserves the vascular barrier by protecting the endothelial glycocalyx. Anesthesiology. 2007;107(5):776–84. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000286984.39328.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chappell D, Jacob M, Hofmann-Kiefer K, Rehm M, Welsch U, Conzen P, Becker BF. Antithrombin reduces shedding of the endothelial glycocalyx following ischaemia/reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83(2):388–96. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peng Z, Pati S, Potter D, Brown R, Holcomb JB, Grill R, Wataha K, Park PW, Xue H, Kozar RA. Fresh frozen plasma lessens pulmonary endothelial inflammation and hyperpermeability after hemorrhagic shock and is associated with loss of syndecan 1. Shock. 2013;40(3):195–202. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31829f91fc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haywood-Watson RJ, Holcomb JB, Gonzalez EA, Peng Z, Pati S, Park PW, Wang W, Zaske AM, Menge T, Kozar RA. Modulation of syndecan-1 shedding after hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Johansson PI, Sorensen AM, Perner A, Welling KL, Wanscher M, Larsen CF, Ostrowski SR. Disseminated intravascular coagulation or acute coagulopathy of trauma shock early after trauma? An observational study. Crit Care. 2011;15(6):R272. doi: 10.1186/cc10553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Johansson PI, Sorensen AM, Perner A, Welling KL, Wanscher M, Larsen CF, Ostrowski SR. Elderly trauma patients have high circulating noradrenaline levels but attenuated release of adrenaline, platelets, and leukocytes in response to increasing injury severity. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(6):1844–50. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823e9d15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johansson PI, Ostrowski SR. Acute coagulopathy of trauma: Balancing progressive catecholamine induced endothelial activation and damage by fluid phase anticoagulation. Med Hypotheses. 2010;75(6):564–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2010.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Johansson PI, Stensballe J, Rasmussen LS, Ostrowski SR. A high admission syndecan-1 level, a marker of endothelial glycocalyx degradation, is associated with inflammation, protein c depletion, fibrinolysis, and increased mortality in trauma patients. Ann Surg. 2011;254(2):194–200. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318226113d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Johansson PI, Stensballe J, Rasmussen LS, Ostrowski SR. High circulating adrenaline levels at admission predict increased mortality after trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(2):428–36. doi: 10.1097/ta.0b013e31821e0f93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Johansson PI, Sorensen AM, Perner A, Welling KL, Wanscher M, Larsen CF, Ostrowski SR. High scd40l levels early after trauma are associated with enhanced shock, sympathoadrenal activation, tissue and endothelial damage, coagulopathy and mortality. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(2):207–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ostrowski SR, Sorensen AM, Windelov NA, Perner A, Welling KL, Wanscher M, Larsen CF, Johansson PI. High levels of soluble vegf receptor-1 early after trauma are associated with shock, sympathoadrenal activation, glycocalyx degradation and inflammation in severely injured patients: A prospective study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2012;20:27. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-20-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nair GB, Niederman MS. Year in review 2012: Critical care - respiratory infections. Crit Care. 2013;17(6):251. doi: 10.1186/cc12773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Croce MA, Brasel KJ, Coimbra R, Adams CA, Jr, Miller PR, Pasquale MD, McDonald CS, Vuthipadadon S, Fabian TC, Tolley EA. National trauma institute prospective evaluation of the ventilator bundle in trauma patients: Does it really work? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(2):354–60. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31827a0c65. discussion 60-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Michetti CP, Fakhry SM, Ferguson PL, Cook A, Moore FO, Gross R Investigators AV-AP. Ventilator-associated pneumonia rates at major trauma centers compared with a national benchmark: A multi-institutional study of the aast. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(5):1165–73. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31824d10fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barbier F, Andremont A, Wolff M, Bouadma L. Hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia: Recent advances in epidemiology and management. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19(3):216–28. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32835f27be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harrington DT, Phillips B, Machan J, Zacharias N, Velmahos GC, Rosenblatt MS, Winston E, Patterson L, Desjardins S, Winchell R, Brotman S, Churyla A, Schulz JT, Maung AA, Davis KA Research Consortium of New England Centers for T. Factors associated with survival following blunt chest trauma in older patients: Results from a large regional trauma cooperative. Arch Surg. 2010;145(5):432–7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jovanovic B, Milan Z, Markovic-Denic L, Djuric O, Radinovic K, Doklestic K, Velickovic J, Ivancevic N, Gregoric P, Pandurovic M, Bajec D, Bumbasirevic V. Risk factors for ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients with severe traumatic brain injury in serbian trauma centre. Int J Infect Dis. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Patel BV, Wilson MR, Takata M. Resolution of acute lung injury and inflammation: A translational mouse model. Eur Respir J. 2012;39(5):1162–70. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00093911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Iskander KN, Craciun FL, Stepien DM, Duffy ER, Kim J, Moitra R, Vaickus LJ, Osuchowski MF, Remick DG. Cecal ligation and puncture-induced murine sepsis does not cause lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):159–70. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182676322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Carles M, Wagener BM, Lafargue M, Roux J, Iles K, Liu D, Rodriguez CA, Anjum N, Zmijewski J, Ricci JE, Pittet JF. Heat-shock response increases lung injury caused by pseudomonas aeruginosa via an interleukin-10-dependent mechanism in mice. Anesthesiology. 2014;120(6):1450–62. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kesimer M, Ehre C, Burns KA, Davis CW, Sheehan JK, Pickles RJ. Molecular organization of the mucins and glycocalyx underlying mucus transport over mucosal surfaces of the airways. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6(2):379–92. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Elfenbein A, Simons M. Syndecan-4 signaling at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(Pt 17):3799–804. doi: 10.1242/jcs.124636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hayashida A, Bartlett AH, Foster TJ, Park PW. Staphylococcus aureus beta-toxin induces lung injury through syndecan-1. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(2):509–18. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pruessmeyer J, Martin C, Hess FM, Schwarz N, Schmidt S, Kogel T, Hoettecke N, Schmidt B, Sechi A, Uhlig S, Ludwig A. A disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17 (adam17) mediates inflammation-induced shedding of syndecan-1 and -4 by lung epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(1):555–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.059394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tanino Y, Chang MY, Wang X, Gill SE, Skerrett S, McGuire JK, Sato S, Nikaido T, Kojima T, Munakata M, Mongovin S, Parks WC, Martin TR, Wight TN, Frevert CW. Syndecan-4 regulates early neutrophil migration and pulmonary inflammation in response to lipopolysaccharide. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;47(2):196–202. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0294OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li Q, Park PW, Wilson CL, Parks WC. Matrilysin shedding of syndecan-1 regulates chemokine mobilization and transepithelial efflux of neutrophils in acute lung injury. Cell. 2002;111(5):635–46. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Venge P, Pedersen B, Hakansson L, Hallgren R, Lindblad G, Dahl R. Subcutaneous administration of hyaluronan reduces the number of infectious exacerbations in patients with chronic bronchitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153(1):312–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.1.8542136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang Q, Teder P, Judd NP, Noble PW, Doerschuk CM. Cd44 deficiency leads to enhanced neutrophil migration and lung injury in escherichia coli pneumonia in mice. Am J Pathol. 2002;161(6):2219–28. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64498-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liang J, Jiang D, Griffith J, Yu S, Fan J, Zhao X, Bucala R, Noble PW. Cd44 is a negative regulator of acute pulmonary inflammation and lipopolysaccharide-tlr signaling in mouse macrophages. J Immunol. 2007;178(4):2469–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.van der Windt Gerritje J, F S, de Vos Alex F, van't Veer Cornelis, Queiroz Karla CS, Liang Jiurong, Jiang Dianhua, Noble Paul W, Tom van der Poll. Cd44 deficiency is associated with increased bacterial clearance but enhanced lung inflammation during gram-negative pneumonia. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(5):2483–94. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lennon FE, Singleton PA. Role of hyaluronan and hyaluronan-binding proteins in lung pathobiology. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301(2):L137–47. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00071.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schmidt EP, Li G, Li L, Fu L, Yang Y, Overdier KH, Douglas IS, Linhardt RJ. The circulating glycosaminoglycan signature of respiratory failure in critically ill adults. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(12):8194–202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.539452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Smith ML, Long DS, Damiano ER, Ley K. Near-wall micro-piv reveals a hydrodynamically relevant endothelial surface layer in venules in vivo. Biophys J. 2003;85(1):637–45. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74507-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ebong EE, Macaluso FP, Spray DC, Tarbell JM. Imaging the endothelial glycocalyx in vitro by rapid freezing/freeze substitution transmission electron microscopy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(8):1908–15. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.225268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mulivor AW, Lipowsky HH. Role of glycocalyx in leukocyte-endothelial cell adhesion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283(4):H1282–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00117.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zeng Y, Ebong EE, Fu BM, Tarbell JM. The structural stability of the endothelial glycocalyx after enzymatic removal of glycosaminoglycans. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yen WY, Cai B, Zeng M, Tarbell JM, Fu BM. Quantification of the endothelial surface glycocalyx on rat and mouse blood vessels. Microvasc Res. 2012;83(3):337–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Job KM, Dull RO, Hlady V. Use of reflectance interference contrast microscopy to characterize the endothelial glycocalyx stiffness. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302(12):L1242–9. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00341.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Giantsos KM, Kopeckova P, Dull RO. The use of an endothelium-targeted cationic copolymer to enhance the barrier function of lung capillary endothelial monolayers. Biomaterials. 2009;30(29):5885–91. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Giantsos-Adams K, Lopez-Quintero V, Kopeckova P, Kopecek J, Tarbell JM, Dull R. Study of the therapeutic benefit of cationic copolymer administration to vascular endothelium under mechanical stress. Biomaterials. 2011;32(1):288–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]