Abstract

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is a profoundly effective treatment for severe obesity, but results in significant bone loss in patients. Developing a murine model that recapitulates this skeletal phenotype will provide a robust tool with which to study the physiologic mechanisms of this bone loss. We studied adult male C57BL/6J mice who underwent either RYGB or sham operation. Twelve weeks after surgery, we characterized biochemical bone markers (parathyroid hormone, PTH; C-telopeptide, CTX; and type 1 procollagen, P1NP) and bone microarchitectural parameters as measured by microcomputed tomography. RYGB-treated mice had significant trabecular and cortical bone deficits compared with sham-operated controls. Although adjustment for final body weight eliminated observed cortical differences, the trabecular bone volume fraction remained significantly lower in RYGB mice even after weight adjustment. PTH levels were similar between groups, but RYGB mice had significantly higher indices of bone turnover than sham controls. These data demonstrate that murine models of RYGB recapitulate patterns of bone loss and turnover that have been observed in human clinical studies. Future studies that exploit this murine model will help delineate the alterations in bone metabolism and mechanisms of bone loss after RYGB.

Keywords: bariatric surgery, gastric bypass, weight loss, obesity, bone loss, bone microarchitecture, mouse models

1. INTRODUCTION

More than one-third of U.S. adults have obesity and the subpopulation of individuals with severe obesity (body mass index, BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2) continues to increase rapidly (1, 2). Bariatric surgery is an increasingly popular and effective treatment for severe obesity, and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is one of the most commonly performed bariatric procedures in the U.S. and worldwide (3).

Despite major improvements in body weight and obesity comorbidities after this operation, clinical studies have documented striking declines in bone mineral density (BMD) of up to 10% (4–12). However, clinical studies have been hampered by their observational study designs and by concerns about obesity-related bone imaging artifact (13, 14). Furthermore, these studies have been unable to tease out the physiological mechanisms of RYGB-induced bone loss and have tested associations without the ability to show direct causation.

Rat and mouse models of RYGB have been established that recapitulate the metabolic improvements observed in human clinical studies (15–18). These surgical models have been utilized in genetically modified mice to identify the physiological and molecular mechanisms through which RYGB imparts its powerful effects on weight loss and improved glucose regulation (19–23). Declining bone density has been documented in rat models of RYGB (24–28), whose evaluation suggests that neither skeletal unloading nor calcium and vitamin D malabsorption are the primary drivers of the associated bone loss. These studies have raised intriguing questions about the etiology of RYGB-induced bone loss, but they have been limited in their ability to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanism(s). By their ability to harness the power of genetic manipulation, mouse bariatric surgery models provide the opportunity to explore the molecular pathophysiology of bone loss. In particular, targeted manipulation of individual pathways can determine their effects on surgically-induced bone loss. Robust mouse models of RYGB that demonstrably recapitulate human physiology have only recently been established, and the skeletal consequences of bariatric surgery in the mouse have not yet been evaluated. We sought to assess the relevance of the mouse model of bariatric surgery for bone disease by determining the effects of RYGB on bone microarchitecture and metabolism in adult mice.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Animals

We evaluated wild-type mice that were part of a larger study examining the effects of 5HT2C-receptor on metabolism after RYGB (29). Male C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME) were placed on a 60% high fat diet (HFD; Research Diets, D12492) at weaning to induce substantial obesity. All surgically treated animals were individually housed and maintained in a 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle under controlled temperature (19–22°C) and humidity (40–60%). All animal studies were performed under protocols approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

2.2 Surgery and postoperative care

Between 23 to 26 weeks of age, diet-induced obese mice were randomized to receive either RYGB surgery (n=6) or laparotomy sham surgery (n=5) under inhalation anesthesia. For these operations, a 2.0–2.5 cm midline abdominal incision was made into the peritoneum and a self-retaining retractor placed at the laparotomy. RYGB anatomy was created as previously described (18). The total length of the small intestine was measured, and as in the typical human operation, a total of 20–30% of the small intestine was included in the combination of Roux and biliopancreatic limbs (approximately 10–15% in each limb). To construct the Roux limb, the jejunum transected 2–3 cm below the ligament of Treitz. Then, 4–5cm beyond the transection, a 2 mm incision was made on the anti-mesenteric wall of the jejunum. A running end-to-side jejuno-jejunal anastomosis was created using 8-0 Vicryl suture (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ). The lesser and greater curvature of the stomach were then dissected and minor branch vessels from the main gastric artery were cauterized around the gastro-esophageal junction to facilitate gastric transection. The gastric pouch and distal gastric remnant were created by transecting the stomach, closing the remnant with a running 8-0 Vicryl suture, and constructing an end-to-end gastro-jejunal anastomosis. Finally, the laparotomy was closed using 6-0 Vicryl suture in two layers. Sham-operated mice were treated in a manner similar to the RYGB mice, but the operation was limited to a laparotomy and surgical repair. Mice were provided with liquid diet (40% Vital AF 1.2 Cal, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) during the 2 weeks immediately following surgery, and were gradually weaned back onto the HFD during this time. All mice were continued on the HFD after surgery to avoid an independent or confounding effect of dietary change. Body weight was monitored weekly, and food intake was measured during post-operative weeks 6–8. One mouse in the RYGB group was excluded from the analysis due to apparent poor health (poor body condition, decreased grooming, decreased mobility, and a body weight that declined to less than 25 g), leaving 5 mice in each of the RYGB and sham groups.

2.3 Specimen harvesting and preparation

At 12 weeks after surgery (age 35–38 weeks), mice were fasted for 4 hours and euthanized by CO2 inhalation. Blood was immediately collected via cardiac puncture. Femurs, tibias, and vertebrae were harvested and cleaned of soft tissue, wrapped in saline-soaked gauze, and stored at −20°C.

2.4 Biochemical assays

Plasma parathyroid hormone (PTH) was assessed by ELISA (Immutopics, San Clemente, CA), an assay with intra-assay precision of 2–6%. Plasma levels of type 1 collagen C-telopeptide (CTX) and amino-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen (P1NP) were measured using mouse ELISA kits (IDS, Fountain Hills, AZ), assays with intra-assay precisions of 5–9%. All assays were batched so as to be performed with a single kit and run according to the manufacturers’ protocols.

2.5 Microarchitecture

Micro-computed tomographic (µCT) imaging was performed on the tibia, femur, and the 5th lumbar (L5) vertebra of mice from each group using a high-resolution desktop imaging system (µCT40, Scanco Medical AG, Brüttisellen, Switzerland). The methods used were in accordance with guidelines for the use of µCT in rodents (30). Scans were acquired using isotropic voxel sizes of 10 µm3 for the tibia and femur and 12 µm3 for the the L5vertebra, with 70 kVp peak x-ray tube potential, 200 ms integration time, and were subjected to Gaussian filtration. Trabecular bone microarchitecture was evaluated in semi-automatically contoured regions in the proximal metaphysis of the tibia, distal metaphysis of the femur, and L5 vertebral body. The region of interest for the proximal tibia began 100 µm below the proximal growth plate and extended distally 1 mm. The region of interest in the distal femur started 200 µm above the peak of the growth plate and extended proximally 1.5 mm. The vertebral body region of interest extended from 120 µm below the cranial growth plate to 120 µm above the caudal growth plate. Cortical bone microarchitecture was evaluated in the tibia mid-diaphysis in a region that started 2 mm above the inferior tibiofibular joint and extended distally 500 µm. Cortical bone microarchitecture was also evaluated in the femoral diaphysis in a region that began 55% of the femoral length below the top of the femoral head and extended distally 500 µm. Segmentation thresholds of 330 and 696 mg HA/cm3 were used for the evaluations of trabecular and cortical bone, respectively, based on adaptive-iterative thresholding (AIT) that was performed on the sham-operated control group. All analyses were carried out using the scanner manufacturer (Scanco Medical) evaluation software. Cancellous bone outcomes included trabecular bone volume fraction (Tb. BV/TV, %), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th, µm), trabecular number (Tb.N, mm−1), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp, µm), connectivity density (Conn.D, mm−3), and structural model index (SMI). Cortical bone outcomes included cortical tissue mineral density (Ct.TMD, mg HA/mm3), cortical thickness (Ct.Th, µm), cortical bone area (Ct.Ar, mm2), total bone area (Tt.Ar, mm2), cortical bone area fraction (Ct.Ar/Tt.Ar, %), cortical porosity (Ct.Po, %), polar moment of inertia (J, mm4), and the maximum and minimum moments of inertia (Imax and Imin, mm4).

2.6 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All data were checked for normality, and standard descriptive statistics computed. Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare differences between RYGB and sham-operated groups. Multivariate regression using PROC GLM was employed to adjust results using final body weight as a covariate. The threshold of statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. Data are reported as mean ± SD, unless otherwise noted.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Body weight

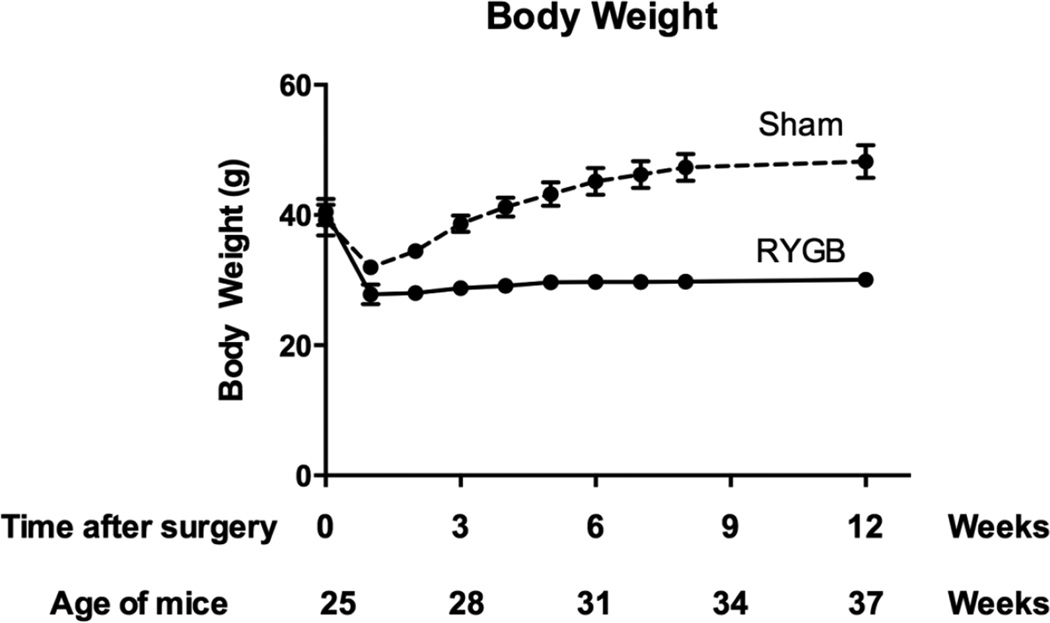

Pre-operative body weight was similar in RYGB-treated and sham-operated groups (40.5 ± 4.7 g and 39.2 ± 5.3 g, respectively). Twelve weeks after surgery, RYGB mice weighed an average 38% less than sham controls (30.1 ± 2.5 g vs. 48.2 ± 5.6 g, p<0.0001; Figure 1). Daily food intake did not differ between groups (RYGB: 3.1 ± 0.6 g/day; Sham: 2.7 ± 0.2 g/day).

Figure 1. Body weight changes in RYGB (solid line) and sham-operated (dashed line) mice.

Between 23 to 26 weeks of age (average 25 weeks), mice were randomized to RYGB or sham surgery and followed for 12 weeks. RYGB mice lost approximately 30% of their initial weight and maintained the loss thereafter, while sham-operated mice exhibited transient weight loss, with subsequent regain to a body weight approximately 20% greater than their initial weight.

3.2 Bone microarchitecture

Twelve weeks after surgery, Tb. BV/TV at the L5 vertebra was 58% lower in the RYGB mice compared to the sham-operated controls (p=0.020; Table 1). There were concurrent declines in Tb.N and Tb.Th, and an increase in Tb.Sp in the RYGB mice as compared with sham controls (p=0.020 for all, Figure 2A). SMI was 93% higher in the RYGB group than sham controls, indicating a more rod-like trabecular architecture in the RYGB group.

TABLE 1.

Trabecular and Cortical Bone Microarchitecture in L5 Vertebrae, Tibia, and Femur of RYGB-treated and Sham-operated Mice

| RYGB | Sham | Percent difference in group medians |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

L5 VERTEBRAE | |||

| Tb.BV/TV (%) | 9.8 (1.5) | 22.6 (2.9) | −57%a,b |

| Tb.N (mm−1) | 3.57 (0.51) | 4.81 (0.26) | −26%a |

| Tb.Sp (mm) | 0.278 (0.044) | 0.195 (0.015) | +43%a |

| Tb.Th (mm) | 0.040 (0.005) | 0.053 (0.004) | −25%a |

| Conn.D (mm−3) | 95.6 (26.5) | 140.6 (10.3) | −32% |

| SMI | 2.10 (0.18) | 1.08 (0.14) | +95%a,b |

|

TIBIA | |||

| Proximal metaphysis trabecular | |||

| Tb.BV/TV (%) | 3.3 (1.0) | 8.8 (0.8) | −63%a,b |

| Tb.N (mm−1) | 2.61 (0.36) | 3.41 (0.20) | −24%a |

| Tb.Sp (mm) | 0.388 (0.054) | 0.288 (0.017) | +35%a |

| Tb.Th (mm) | 0.045 (0.005) | 0.062 (0.003) | −28%a |

| Conn.D (mm−3) | 5.5 (3.5) | 21.7 (9.9) | −75%a,b |

| SMI | 3.54 (0.10) | 3.06 (0.34) | +16% |

| Midshaft cortical | |||

| Ct.TMD (mgHA/cm3) | 1142 (17) | 1187 (13) | −4%a |

| Tt.Ar (mm2) | 1.21 (0.12) | 1.25 (0.23) | −4% |

| Ct.Ar (mm2) | 0.42 (0.03) | 0.60 (0.69) | −30%a |

| Ct.Ar/Tt.Ar (%) | 37.4 (4.4) | 50.3 (6.2) | −26%a |

| Ct.Th (mm) | 0.12 (0.01) | 0.19 (0.02) | −36%a |

| Ct.Po (%) | 0.34 (0.01) | 0.22 (0.04) | +52%a |

| J (mm4) | 0.14 (0.03) | 0.20 (0.05) | −30% |

| Imax (mm4) | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.12 (0.02) | −31% |

| Imin (mm4) | 0.06 (0.01) | 0.08 (0.02) | −27% |

|

FEMUR | |||

| Distal metaphysis trabecular | |||

| Tb.BV/TV (%) | 3.3 (0.9) | 7.6 (1.1) | −57%a |

| Tb.N (mm−1) | 2.42 (0.09) | 3.12 (0.27) | −22%a,b |

| Tb.Sp (mm) | 0.414 (0.012) | 0.308 (0.029) | +34%a,b |

| Tb.Th (mm) | 0.044 (0.005) | 0.061 (0.007) | −28%a |

| Conn.D (mm−3) | 10.9 (6.9) | 26.1 (6.3) | −58%a |

| SMI | 3.11 (0.20) | 2.96 (0.24) | +5% |

| Midshaft cortical | |||

| Ct.TMD (mgHA/cm3) | 1093 (27) | 1153 (21) | −5%a |

| Tt.Ar (mm2) | 2.20 (0.42) | 2.35 (0.50) | −6% |

| Ct.Ar (mm2) | 0.54 (0.11) | 0.81 (0.02) | −33%a |

| Ct.Ar/Tt.Ar (%) | 24.6 (3.0) | 34.5 (6.3) | −29%a |

| Ct.Th (mm) | 0.10 (0.02) | 0.15 (0.01) | −32%a |

| Ct.Po (%) | 0.36 (0.15) | 0.20 (0.03) | +77%a |

| J (mm4) | 0.31 (0.04) | 0.54 (0.13) | −43%a |

| Imax (mm4) | 0.20 (0.02) | 0.38 (0.08) | −46%a |

| Imin (mm4) | 0.11 (0.03) | 0.17 (0.04) | −32% |

Values reported are median (interquartile range)

indicates unadjusted p-values ≤0.05

indicates weight-adjusted p-values ≤0.05

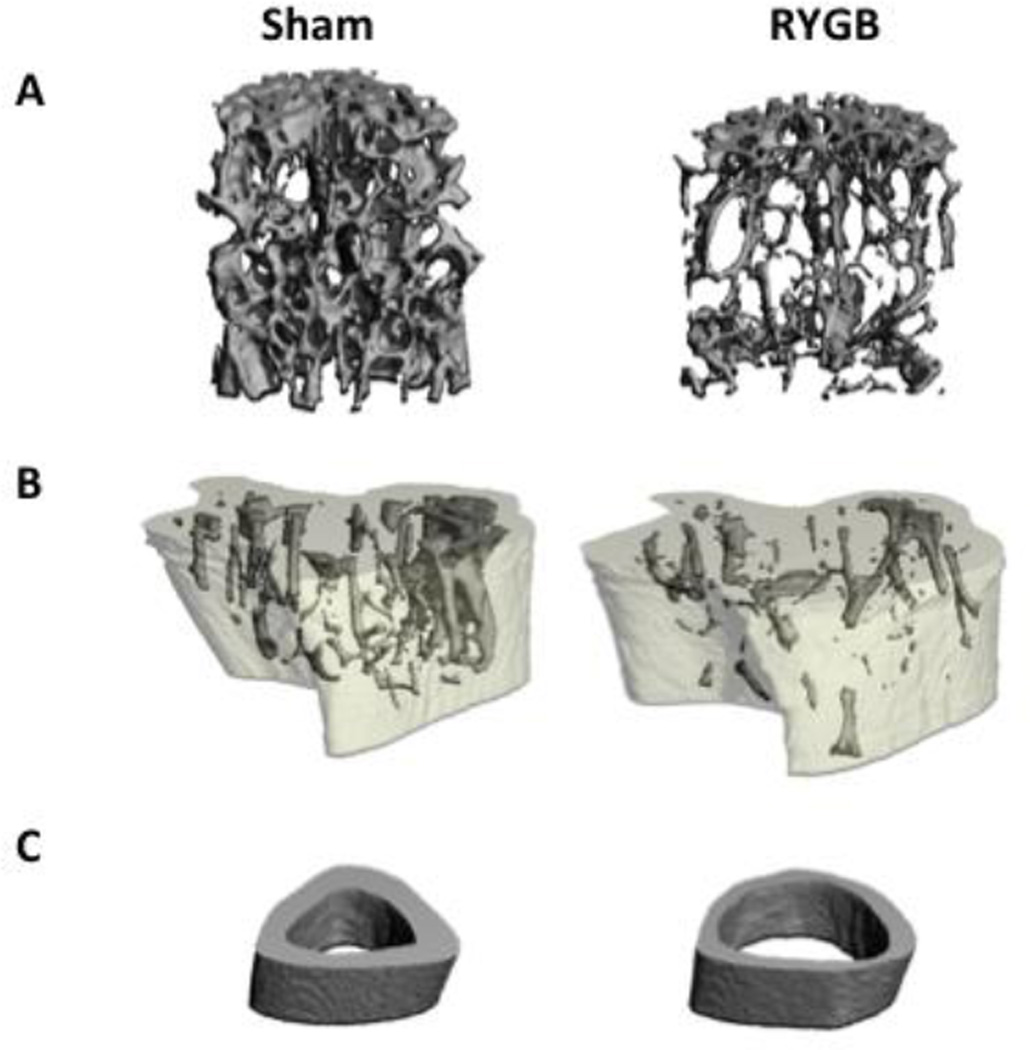

Fig. 2. Representative images of bone microarchitecture in RYGB (right) and sham-operated (left) mice.

Defects in trabecular microarchitecture are apparent after RYGB at the L5 vertebrae (A). Abnormal bone geometry and microarchitecture are shown after RYGB at the proximal tibia metaphysis (B) and mid-shaft tibia (C).

At the proximal tibia, Tb. BV/TV was 63% lower in the RYGB mice than in the sham-operated controls (p<0.001; Table 1). Tb.N, Tb.Th, and Conn.D were also lower in the RYGB mice, whereas Tb.Sp was higher than in sham-operated controls (p<0.05 for all; Figure 2B). At the tibial midshaft, Ct.TMD (−4%, p=0.022), Ct.Ar/Tt.Ar (−26%, p=0.012) and Ct.Th (−36%, p<0.012) were all significantly lower in the RYGB group than in sham controls (Figure 2C). A similar pattern of results were seen at the femur, with disruption of trabecular microarchitecture at the distal femoral metaphysis and weakening of cortical microarchitecture at the femoral midshaft (Table 1).

Adjustment for final body weight diminished the differences between groups in cortical microarchitecture at the tibia and the femur (Table 1). However, weight-adjusted Tb. BV/TV were significantly lower in the RYGB group at the tibia (p=0.034) and at the spine (p=0.006). Several other trabecular differences between RYGB mice and sham controls persisted after adjusting for differences in body weight.

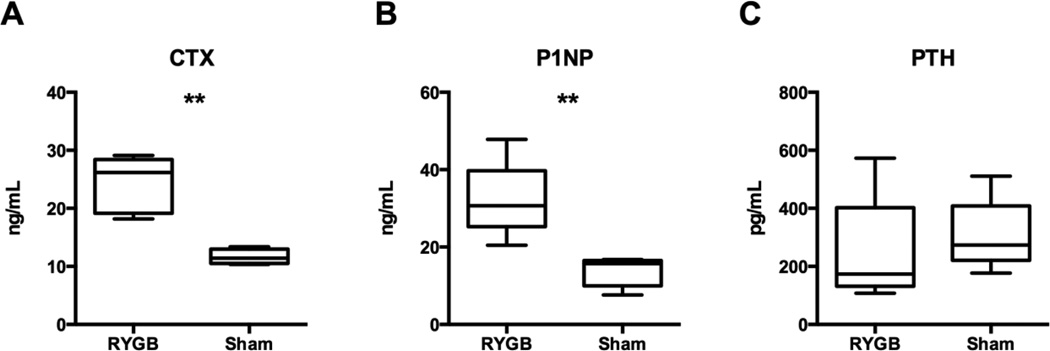

3.3 Bone turnover markers and PTH

At study end, P1NP and CTX levels were respectively 132% and 109% higher after RYGB than sham-operated controls (Figure 3A/B, p=0.005). PTH levels were similar in the RYGB and sham mice (Figure 3C).

Fig. 3. Indices of bone turnover and PTH levels in RYGB and sham-operated mice.

Boxplots showing median, interquartile range, maximum and minimum values are displayed. Twelve weeks after surgery, CTX (A) and P1NP (B) levels were significantly greater in the RYGB mice than in sham controls. There was no difference in PTH between RYGB and sham groups (C). ** p ≤ 0.005.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated significant cortical and trabecular bone deficits in obese male mice after RYGB. Indices of bone turnover, including CTX and P1NP, were markedly higher in the RYGB-treated mice than in sham-operated controls, despite a lack of difference in PTH levels between these groups. These data demonstrate that murine models of RYGB reflect similar patterns of bone loss and increases in bone turnover as have been observed in human clinical studies.

Importantly, the results from this study closely parallel the findings of human clinical studies with deterioration of both cortical and trabecular compartments. Clinical studies using high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) have demonstrated that bariatric surgery is accompanied by declines in cortical and trabecular bone density and microarchitecture at both the radius and tibia (8, 12). RYGB also leads to declines in trabecular density at the lumbar spine and proximal femur by QCT (8). In this murine model, RYGB induced significant negative effects on both cortical and trabecular bone at the lumbar spine, distal femur, and proximal tibia. The current study avoids concern about the influence of soft tissue artifact on bone imaging, as we had the opportunity to examine excised specimens directly. These results are similar to skeletal phenotypes previously observed after RYGB in both obese and non-obese rats (24, 25)(26–28). Further understanding of the mechanisms of RYGB effects on bone morphology and metabolism will benefit from the use of this mouse model as a physiologically relevant means of testing mechanistic hypotheses regarding bone loss after RYGB.

This preliminary study does not directly address the etiology of skeletal changes after RYGB. However, we observed a skeletal phenotype in the RYGB group despite having similar PTH levels as the sham-operated controls. Although sampling limitations precluded determination of serum calcium and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, the absence of a difference in PTH between groups suggests that secondary hyperparathyroidism is unlikely to drive the dramatic changes we observed in post-RYGB bone metabolism. Although earlier studies in rats suggested that minor changes in calcium and vitamin D homeostasis may occur in the absence of secondary hyperparathyroidism (26–28), dietary supplementation to prevent calcium and 25-hydroxyvitamin D fluctuations did not fully rescue bone density after RYGB (27). The current findings are also consistent with human studies that demonstrate significant bone loss and increases in bone turnover markers after RYGB in the absence of significant changes in either 25-hydroxyvitamin D or PTH (7–11, 31). Some investigators have proposed that metabolic acidosis, which has been observed in rat models of RYGB (26, 28), may induce hypercalciuria that contributes to bone loss. Metabolic acidosis has not been observed in human studies, however, and clinical studies have documented significant declines in urine calcium after RYGB (32, 33).

Finally, it is important to note that differences in body weight after RYGB may lead to mechanical unloading of the skeleton. In clinical studies, it has been shown that diet-induced weight loss of 10–20% can lead to modest bone loss, with declines in hip BMD of 1–3% (34)(35) and increases in serum CTX of 20–35% (36, 37). In the mouse model, there was a significant post-operative weight difference between RYGB and sham controls, an expected consequence of successful metabolic surgery. Adjustment for body weight diminished the cortical differences between RYGB and sham groups, suggesting that mechanical unloading from weight loss may have contributed to the observed cortical decline. Given the powerful physiological effects of RYGB on energy balance and multiple metabolic functions, however, the coincident loss of weight and cortical bone may reflect common or overlapping physiological effects. Several lines of evidence from both human and animal studies suggest that factors other than skeletal unloading likely contribute to RYGB-induced bone loss. Recent clinical studies in RYGB patients demonstrate inconsistent associations between weight loss and bone loss (4, 5, 38). Moreover, increases in bone resorption observed after RYGB have been shown to far exceed those observed after complete bedrest (39), providing further support that mechanisms beyond mechanical unloading are contributing to the bone loss. Similarly, bone loss in calorie-restricted rats is substantially attenuated in comparison to their weight-matched, RYGB-treated counterparts (26). Lastly, alterations in bone volume are observed in the rat RYGB model but not in a rat sleeve gastrectomy model despite similar weight loss, further supporting the hypothesis that a RYGB-specific mechanism may drive the observed skeletal declines (27). In this mouse model, several of the observed trabecular defects after RYGB remained clinically and statistically significant after adjustment for final body weight, underscoring the likely importance of weight-independent bone loss. It remains to be seen whether bone loss after RYGB is being driven by one of the multitude of physiological and signaling systems known to be influenced by RYGB, including those mediated by gastrointestinal peptide hormones, bile acids, intestinal microbiota, and enhanced thermogenesis. We have recently demonstrated that increases in bone resorption markers after RYGB in human patients are correlated with increases in peptide YY (40), a neuropeptide hypothesized to have direct effects on the skeleton (41). Future studies in mice genetically modified to enhance or diminish peptide YY secretion or signaling could provide valuable insight into this possibility.

This preliminary study has several limitations. The absence of a sham-operated control group that was weight-matched to the RYGB-treated mice by calorie restriction prevents certain conclusion that the observed bone loss is weight-loss-independent. Future studies will be needed to explore this potentially important mechanism. Applicability of results from the mouse model to human patients is not a given, as there may be important interspecies differences in gastrointestinal and/or skeletal physiology. Such interspecies differences have been observed in other responses to RYGB including in the relative contribution of thermogenesis to weight loss, and glucose disposal into muscle to ameliorate diabetes. Nonetheless, numerous studies of the response to RYGB in rodents and humans demonstrate highly conserved mechanisms with variations in the relative use of these mechanisms in the different species, thus rendering the mouse a good model for primary mechanistic discovery. Another consideration is the exposure to and maintenance of a very high (60%) fat diet throughout these studies. Maintaining mice on this diet postoperatively was necessary to examine the diet-independent effects of the surgery. While we have observed no effect of this diet alone on bone microarchitecture, we cannot exclude the possibility that the diet used might influence the metabolic outcomes of the surgery, either enhancing or limiting its impact on bone phenotype. Finally, precise assessment of cortical porosity in mice is difficult due to limitations in microCT imaging resolution, and we may therefore miss smaller microscopic cortical pores (<20 µm diameter). Acknowledging this caveat, the ability to detect higher measured cortical porosity in RYGB mice, similar to what has been observed after RYGB in humans utilizing HR-pQCT, suggests that the imaging approach used in these mice is sufficient (8, 12).

5. CONCLUSION

We have demonstrated that a murine model of RYGB recapitulates the skeletal phenotype of bone loss that has been observed in human patients after the same operation. Future studies will be needed to address how bone loss after RYGB may be modulated by age, sex, or gonadal status of the mice, and to further investigate mechanisms by which RYGB may stimulate weight-loss independent bone loss. We expect that this murine model will be a powerful tool to delineate and characterize mechanisms by which gastrointestinal derived signals influence bone metabolism, and will help to identify clinically-relevant targets for the development of treatments that mitigate surgery and diet-related bone decline.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Murine models of RYGB recapitulate patterns of bone loss and turnover previously observed in human clinical studies

RYGB-operated mice had significant trabecular and cortical bone deficits, and increased bone turnover as compared with sham-operated controls

Future studies can leverage this murine model to delineate alterations in bone metabolism and mechanisms of bone loss after RYGB

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Nicholas P. Derrico, Miranda Van Vliet, Phil Davis, Andrew Johnston, Matthew Scott, and Shubhra Kashyap for their technical assistance, and Dorothy Pazin for her critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants DK093713 (E.W.Y.), DK088661 (L.M.K.) and a research grant from Ethicon, Inc.

ABBREVIATIONS

- RYGB

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

- PTH

parathyroid hormone

- CTX

C-telopeptide, CTX

- P1NP

type 1 procollagen

- BMI

body mass index

- BMD

bone mineral density

- µCT

micro-computed tomography

- Tb. BV/TV

trabecular bone volume fraction

- Tb.Th

trabecular thickness

- Tb.N

trabecular number

- Tb.Sp

trabecular separation

- Conn.D

connectivity density

- SMI

structural model index

- Ct.TMD

cortical tissue mineral density

- Ct.Th

cortical thickness

- Ct.Ar

cortical bone area

- Tt.Ar

total bone area

- Ct.Ar/Tt.Ar

cortical bone area fraction

- Ct.Po

cortical porosity

- J

polar moment of inertia

- Imax

maximum moment of inertia

- Imin

minimum moments of inertia

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity, and Extreme Obesity Among Adults: United States, Trends 1960–1962 Through 2009–2010. 2012 In. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311:806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/Bariatric Surgery Worldwide 2011. Obesity Surgery. 2013;23:427–436. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0864-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrasco F, Ruz M, Rojas P, Csendes A, Rebolledo A, Codoceo J, Inostroza J, Basfi-Fer K, Papapietro K, Rojas J, Pizarro F, Olivares M. Changes in Bone Mineral Density, Body Composition and Adiponectin Levels in Morbidly Obese Patients after Bariatric Surgery. OBES SURG. 2009;19:41–46. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9638-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleischer J, Stein EM, Bessler M, Della Badia M, Restuccia N, Olivero-Rivera L, McMahon DJ, Silverberg SJ. The decline in hip bone density after gastric bypass surgery is associated with extent of weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3735–3740. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Mach M-A, Stoeckli R, Bilz S, Kraenzlin M, Langer I, Keller U. Changes in bone mineral content after surgical treatment of morbid obesity. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2004;53:918–921. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlin AM, Rao DS, Yager KM, Parikh NJ, Kapke A. Treatment of vitamin D depletion after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a randomized prospective clinical trial. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2009;5:444–449. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu EW, Bouxsein ML, Putman MS, Monis EL, Roy AE, Pratt JS, Butsch WS, Finkelstein JS. Two-Year Changes in Bone Density After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-4341. (in press as of Jan 2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casagrande DS, Repetto G, Mottin CC, Shah J, Pietrobon R, Worni M, Schaan BD. Changes in Bone Mineral Density in Women Following 1-Year Gastric Bypass Surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2012;22:1287–1292. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0687-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vilarrasa N, San José P, García I, Gómez-Vaquero C, Medina Miras P, Gordejuela AGR, Masdevall C, Pujol J, Soler J, Gómez JM. Evaluation of Bone Mineral Density Loss in Morbidly Obese Women After Gastric Bypass: 3-Year Follow-Up. Obesity Surgery. 2011;21:465–472. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0338-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coates PS, Fernstrom JD, Fernstrom MH, Schauer PR, Greenspan SL. Gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity leads to an increase in bone turnover and a decrease in bone mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1061–1065. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein EM, Carrelli A, Young P, Bucovsky M, Zhang C, Schrope B, Bessler M, Zhou B, Wang J, Guo XE, McMahon DJ, Silverberg SJ. Bariatric Surgery Results in Cortical Bone Loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:541–549. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolotin HH. DXA in vivo BMD methodology: an erroneous and misleading research and clinical gauge of bone mineral status, bone fragility, and bone remodelling. Bone. 2007;41:138–154. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu EW, Thomas BJ, Brown JK, Finkelstein JS. Simulated increases in body fat and errors in bone mineral density measurements by DXA and QCT. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:119–112. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashrafian H, Bueter M, Ahmed K, Suliman A, Bloom SR, Darzi A, Athanasiou T. Metabolic surgery: an evolution through bariatric animal models. Obesity Reviews. 2010;11:907–920. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao RS, Rao V, Kini S. Animal Models in Bariatric Surgery—A Review of the Surgical Techniques and Postsurgical Physiology. Obesity Surgery. 2010;20:1293–1305. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stylopoulos N, Hoppin AG, Kaplan LM. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass enhances energy expenditure and extends lifespan in diet-induced obese rats. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:1839–1847. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.207. PMC4157127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liou AP, Paziuk M, Luevano JM, Jr, Machineni S, Turnbaugh PJ, Kaplan LM. Conserved shifts in the gut microbiota due to gastric bypass reduce host weight and adiposity. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:178ra141. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005687. PMC3652229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatoum IJ, Stylopoulos N, Vanhoose AM, Boyd KL, Yin DP, Ellacott KL, Ma LL, Blaszczyk K, Keogh JM, Cone RD, Farooqi IS, Kaplan LM. Melanocortin-4 receptor signaling is required for weight loss after gastric bypass surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1023–E1031. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3432. PMC3387412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryan KK, Tremaroli V, Clemmensen C, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Myronovych A, Karns R, Wilson-Perez HE, Sandoval DA, Kohli R, Backhed F, Seeley RJ. FXR is a molecular target for the effects of vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Nature. 2014;509:183–188. doi: 10.1038/nature13135. PMC4016120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liou AP, Paziuk M, Luevano JM, Machineni S, Turnbaugh PJ, Kaplan LM. Conserved Shifts in the Gut Microbiota Due to Gastric Bypass Reduce Host Weight and Adiposity. Science Translational Medicine. 2013;5:178ra141–178ra141. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zechner JF, Mirshahi UL, Satapati S, Berglund ED, Rossi J, Scott MM, Still CD, Gerhard GS, Burgess SC, Mirshahi T, Aguirre V. Weight-independent effects of roux-en-Y gastric bypass on glucose homeostasis via melanocortin-4 receptors in mice and humans. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:580–590. e587. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.11.022. PMC3835150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mokadem M, Zechner JF, Uchida A, Aguirre V. Leptin Is Required for Glucose Homeostasis after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass in Mice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139960. PMC4596552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stenstrom B, Furnes M, Tommeras K, Syversen U, Zhao C, Chen D. Mechanism of Gastric Bypass–Induced Body Weight Loss: One-Year Follow-up After Micro–Gastric Bypass in Rats. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2006;10:1384–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pérez-Castrillón JL, Riancho JA, Luis D, Caeiro JR, Guede D, González-Sagrado M, Ruiz-Mambrilla M, Domingo-Andrés M, Conde R, Primo-Martín D. The Deleterious Effect of Bariatric Surgery on Cortical and Trabecular Bone Density in the Femurs of Non-obese, Type 2 Diabetic Goto-Kakizaki Rats. Obesity Surgery. 2012;22:1755–1760. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0732-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abegg K, Gehring N, Wagner CA, Liesegang A, Schiesser M, Bueter M, Lutz TA. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery reduces bone mineral density and induces metabolic acidosis in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;305:R999–R1009. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00038.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stemmer K, Bielohuby M, Grayson BE, Begg DP, Chambers AP, Neff C, Woods SC, Erben RG, Tschöp MH, Bidlingmaier M, Clemens TL, Seeley RJ. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery but not vertical sleeve gastrectomy decreases bone mass in male rats. Endocrinology. 2013;154:2015–2024. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canales BK, Schafer AL, Shoback DM, Carpenter TO. Gastric bypass in obese rats causes bone loss, vitamin D deficiency, metabolic acidosis, and elevated peptide YY. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:878–884. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.01.021. PMC4113565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carmody JS, Ahmad NN, Machineni S, Lajoie S, Kaplan LM. Weight loss after RYGB is independent of and complementary to serotonin 2C receptor signaling in male mice. Endocrinology. 2015 doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1226. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouxsein ML, Boyd SK, Christiansen BA, Guldberg RE, Jepsen KJ, Müller R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2010;25:1468–1486. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsiftsis DDA, Mylonas P, Mead N, Kalfarentzos F, Alexandrides TK. Bone Mass Decreases in Morbidly Obese Women after Long Limb-Biliopancreatic Diversion and Marked Weight Loss Without Secondary Hyperparathyroidism. A Physiological Adaptation to Weight Loss? OBES SURG. 2009;19:1497–1503. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9938-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riedt CS, Brolin RE, Sherrell RM, Field MP, Shapses SA. True fractional calcium absorption is decreased after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Obesity. 2006;14:1940–1948. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.226. PMC4016232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schafer AL, Sellmeyer D, Weaver C, Wheeler A, Stewart L, Rogers S, Carter J, Posselt A, Black D, Shoback DM. American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. Houston, TX: 2014. Intestinal Calcium Absorption Decreases Dramatically After Gastric Bypass Surgery, Despite Optimization of Vitamin D Status. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villareal DT, Fontana L, Weiss EP, Racette SB, Steger-May K, Schechtman KB, Klein S, Holloszy JO. Bone mineral density response to caloric restriction-induced weight loss or exercise-induced weight loss: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Int Med. 2006;166:2502–2510. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.22.2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villareal DT, Chode S, Parimi N, Sinacore DR, Hilton T, Armamento-Villareal R, Napoli N, Qualls C, Shah K. Weight Loss, Exercise, or Both and Physical Function in Obese Older Adults. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:1218–1229. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hinton PS, LeCheminant JD, Smith BK, Rector RS, Donnelly JE. Weight loss-induced alterations in serum markers of bone turnover persist during weight maintenance in obese men and women. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2009;28:565–573. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2009.10719788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Redman LM, Rood J, Anton SD, Champagne C, Smith SR, Ravussin E Pennington Comprehensive Assessment of Long-Term Effects of Reducing Intake of Energy Research T. Calorie restriction and bone health in young, overweight individuals. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1859–1866. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.17.1859. PMC2748345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu EW, Bouxsein M, Roy AE, Baldwin C, Cange A, Neer RM, Kaplan LM, Finkelstein JS. Bone loss after bariatric surgery: Discordant results between DXA and QCT bone density. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:542–550. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Belavy DL, Baecker N, Armbrecht G, Beller G, Buehlmeier J, Frings-Meuthen P, Rittweger J, Roth HJ, Heer M, Felsenberg D. Serum sclerostin and DKK1 in relation to exercise against bone loss in experimental bed rest. J Bone Miner Metab. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00774-015-0681-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu EW, Wewalka M, Ding S, Simonson DC, Foster K, Holst J, Vernon A, Goldfine A, Halperin F. Effects of Gastric Bypass and Gastric Banding on Bone Remodeling in Obese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-3437. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong IP, Driessler F, Khor EC, Shi YC, Hormer B, Nguyen AD, Enriquez RF, Eisman JA, Sainsbury A, Herzog H, Baldock PA. Peptide YY regulates bone remodeling in mice: a link between gut and skeletal biology. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]