Abstract

Background

Ecstasy (MDMA) in the US is commonly adulterated with other drugs, but research has not focused on purity of ecstasy since the phenomenon of “Molly” (ecstasy marketed as pure MDMA) arose in the US.

Methods

We piloted a rapid electronic survey in 2015 to assess use of novel psychoactive substances (NPS) and other drugs among 679 nightclub/festival-attending young adults (age 18–25) in New York City. A quarter (26.1%) of the sample provided a hair sample to be analyzed for the presence of select synthetic cathinones (“bath salts”) and some other NPS. Samples were analyzed using fully validated UHPLC-MS/MS methods. To examine consistency of self-report, analyses focused on the 48 participants with an analyzable hair sample who reported lifetime ecstasy/MDMA/Molly use.

Results

Half (50.0%) of the hair samples contained MDMA, 47.9% contained butylone, and 10.4% contained methylone. Of those who reported no lifetime use of “bath salts”, stimulant NPS, or unknown pills or powders, about four out of ten (41.2%) tested positive for butylone, methylone, alpha-PVP, 5/6-APB, or 4-FA. Racial minorities were more likely to test positive for butylone or test positive for NPS after reporting no lifetime use. Frequent nightclub/festival attendance was the strongest predictor of testing positive for MDMA, butylone, or methylone.

Discussion

Results suggest that many ecstasy-using nightclub/festival attendees may be unintentionally using “bath salts” or other NPS. Prevention and harm reduction education is needed for this population and “drug checking” (e.g., pill testing) may be beneficial for those rejecting abstinence.

Keywords: ecstasy, novel psychoactive substances, nightclubs, dance festivals, synthetic cathinones

1. INTRODUCTION

Ecstasy —a common street name for 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)—is one of the most prevalent party drugs in the US. About one out of ten young adults in the US are estimated to have used ecstasy in their lifetime. Specifically, in 2013, 12.8% of young adults (age 18–25) in a nationally representative sample reported lifetime ecstasy use (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2014), and in 2014, 11.4% of young adults (age 19–28) in another nationally representative sample reported lifetime use (Miech et al., 2015). However, targeted samples of nightclub attendees suggest that rates of use are much higher among those who attend nightclubs or raves where electronic dance music (EDM) events are held (Kelly et al., 2006; Ross et al., 2003).

Ecstasy use can place users at risk for acute and long-term adverse health outcomes (Hall and Henry, 2006; Parrott, 2013), and between 2005 and 2011, emergency department (ED) visits related to ecstasy use increased in the US from 4,460 to 10,176 among those age 21 and under (SAMHSA, 2013a). Although recent national rates of ecstasy-related ED visits are not available, reported poisonings related to use of “hallucinogenic amphetamines” (e.g., MDMA) in the US rose from 2,057 in 2009 to 2,514 in 2013 (Bronstein et al., 2010; Mowry et al., 2013). However, increases in poisonings appear to correspond to increasing popularity of the new street name for ecstasy— “Molly”.

While ecstasy, traditionally, has been manufactured and sold in pill form, in the US, ecstasy is now commonly available in powder and crystalline forms, and these new forms are commonly referred to as “Molly”. Molly is short for “molecular”, as it implies that the product is pure MDMA; however, ecstasy or Molly can contain novel psychoactive substances (NPS) that are potentially even more dangerous than MDMA. Older studies conducted in the US (Baggott et al., 2000; Tanner-Smith, 2006) and in Europe (Parrott, 2004; Wood et al., 2011; Vogels et al., 2009) have found adulterant drugs in ecstasy, and more recently, a Spanish study found synthetic cathinones (a.k.a.: “bath salts”) in many samples submitted to a drug testing service (Caudevilla-Gálligo et al., 2013). However, it is unknown how many products analyzed in this Spanish study were sold as “ecstasy”, and the majority of samples (90%) were in powder or crystalline form (Caudevilla-Gálligo et al., 2013). In another study, researchers conducted a retrospective analysis of hair samples that previously tested positive for MDMA or amphetamine and many hair samples also contained piperazines and some samples contained mephedrone (a synthetic cathinone; Rust et al., 2012). However, it is not known whether individuals used these NPS unknowingly, thinking it was ecstasy.

Hundreds of NPS have emerged in recent years (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction [EMCDDA], 2015; US Drug Enforcement Administration [DEA], 2015), and both the scientific community and users often lack adequate information about effects of these new drugs. Synthetic cathinones (a.k.a.: “bath salts”) are of particular concern because some drugs in this class (e.g., mephedrone, methylone) have served as replacements for ecstasy (Carhart-Harris et al., 2011; Kapitány-Fövény et al., 2013). While effects of some synthetic cathinones are reportedly similar to effects of ecstasy or other stimulants (Brunt et al., 2011; Carhart-Harris et al., 2011), use has been associated with many adverse health outcomes (Miotto et al., 2013; Zawilska and Wojcieszak, 2013; Zawilska and Andrzejczak, 2015), including over 20,000 ED visits in the US in 2011 (SAMHSA, 2013b). In 2011, there were 6,137 poisonings reportedly related to “bath salt” use in the US (American Association of Poison Control Centers [AAPCC], 2015). While reported poisonings related to “bath salt” use decreased in the US through 2015 (to 520) (AAPCC, 2015), users may not always know the actual drug they are taking as drugs sold as ecstasy may contain NPS such as synthetic cathinones (Brunt et al., 2011). Poisonings and deaths at dance festivals in the US have also recently occurred related to methylone use—taken alone or in combination with MDMA (Ridpath et al., 2014)—and users may not have known they were ingesting a synthetic cathinone. Thus, it is of concern that “ecstasy”-related adverse outcomes in recent years may be linked to increasing adulteration of ecstasy with synthetic cathinones and other NPS.

The nightclub and dance festival scene is at particularly high risk for unintentional use of synthetic cathinones and other NPS so research is needed to examine the extent to which ecstasy users are unknowingly using these substances. To our knowledge, no recent studies have examined purity of ecstasy in the US, and moreover, studies have not examined whether ecstasy users are using “bath salts” and/or other NPS unknowingly or unintentionally.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants and Procedure

We surveyed 679 nightclub and festival attendees in New York City (NYC) from July through early September of 2015 using a variation of time-space sampling. Eligible participants were those who 1) identified as ages 18–25, and 2) were about to attend the randomly selected party. After providing informed consent, participants completed the computer-assisted personal interview on tablet computers. Those who completed the survey were compensated $10 cash. Upon completion, participants were asked if they would be willing to provide a hair sample to be tested for “drugs such as ‘bath salts’”. If the participant agreed, the trained recruiter collected the sample by cutting a small lock of hair (~100 hairs) from as close to the participant’s scalp as possible. Hair was cut with a clean scissor (wiped with an alcohol-wipe after each use), folded up in a piece of tin foil, and stored in a small envelope labeled with the participant’s anonymous study ID number (which was linked to his or her survey responses). Some males expressed interest in providing a sample, but their hair was too short, which often prevented us from being able to obtain an adequate (analyzable) sample. In some cases, male participants volunteered to have the recruiter to clip or buzz (with an electronic buzzer) body hair from the arm, chest, or leg. This study was approved by the New York University Langone Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

The response rate (for the survey) of those approached who were believed to be eligible was 63%. Of the 679 participants surveyed, a quarter (n = 177, 26.1%) provided a hair sample. In this study, we evaluated a cohort composed of 48 participants who reported lifetime ecstasy use and had a hair sample compatible with the quantity needed for the analysis (see Section 2.3).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics and Nightlife Attendance

Participants were asked their age, sex, race/ethnicity, level of educational attainment, and weekly income (Palamar et al., 2015a). We also asked, “How often do you go to rave/nightclub/festival/dance parties?” with answer options: never, a few times a year, once or twice a month, at least once a week, and almost every day (Miech et al., 2015; Palamar et al., 2015a). Answers were recoded into: 1) attend less than once a week and 2) attend at least once a week. We also created a variable indicating whether the participant was surveyed outside of a nightclub or a dance festival.

2.2.2. Drug Use

Participants were asked: “Have you ever (knowingly) used ecstasy/MDMA/Molly?” Those who answered affirmatively were also asked to check off which type(s) of ecstasy they had used and answer options included MDMA pills, MDMA powder/Molly, and MDMA crystals. Ecstasy users were also asked if they had ever suspected their ecstasy/Molly contained a drug other than MDMA. Self-reported lifetime use of a variety of other drugs (>200) was assessed with a special focus on NPS. Specifically, participants were provided with lists of drugs (along with common street names when available) belonging to specific NPS classes and asked whether they had ever knowingly used. This paper focuses mainly on self-reported “bath salt” use, in which participants were asked whether they had ever knowingly used any of 35 listed “bath salts” (e.g., alpha-PVP [“Flakka”], methylone [“M1”, “bk-MDMA”], butylone [“B1”, “bk-MBDB”], mephedrone [“MCAT”, “Meow Meow”], “bath salt unknown or not listed”). If they checked off that they had used any, we categorized them into lifetime “bath salt” users. We also asked about a variety of other stimulant NPS such as 4-FMA, BZP, and 2-DPMP (“Ivory Wave”), and we asked participants whether they had ever knowingly used unknown powders or unknown pills to get high. Participants were also able to type in names of other drugs they used that we did not ask about.

2.3. Hair analyses

Hair samples collected from heads, as well as samples collected from other body parts, were analyzed in their full length. The average length was 9.9 cm (median 9.0 cm). Assuming normal hair growth rate (Kintz, 2013), the corresponding mean time frame is 1 cm per month. A minimum quantity of 20 mg was needed to perform the analysis. The collected hair specimens were tested using two previously published methods using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS). One (Di Corcia et al, 2012) was used to screen each sample for 11 common drugs of abuse or metabolites: morphine, 6-acetylmorphine, codeine, amphetamine, methamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), MDMA, 3,4-methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDEA), cocaine, benzoylecgonine and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). The second method (Salomone et al., 2015) was capable of detecting the most likely common NPS—namely stimulants and psychedelic substituted phenethylamines: mephedrone, 3-methylmethcathinone (3-MMC), 4-methylethcathinone (4-MEC), methylone, 4-fluoroamphetamine (4-FA), 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), pentedrone, ethcathinone, alpha-pyrrolidinovalerophenone (α-PVP), butylone, buphedrone, 25I-NBOMe, 25C-NBOMe, 25H-NBOMe, 25B-NBOMe, 2C-P, 2C-B, 1-(benzofuran-5-yl)-N-methylpropan-2-amine (5-MAPB), 5-(2-aminopropyl)benzofuran (5-APB)/6-(2-aminopropyl)benzofuran (6-APB), para-methoxymethamphetamine (PMMA), para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA), amfepramone, meta-chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP), plus 3 dissociative NPS—methoxetamine (MXE), 4-methoxyphencyclidine (4-MeO-PCP), and diphenidine. Specimens were also tested for two dissociative non-NPS: ketamine and phencyclidine (PCP). The new designer drug mCPP can be detected in biological fluids as a metabolite of trazodone (Lendoiro et al., 2014); therefore, trazodone was also included in our method in order to discriminate between direct mCPP intake and biotransformation of trazodone. We also tested for the presence of bupropion as its recreational use has been reported (McCormick, 2002). The limits of detection (LOD) of the analytical methods (Di Corcia et al., 2012; Salomone et al., 2015) were set as the minimum criterion to identify the positive samples. Positive identification criteria of target substances at LOD included coincidence of chromatographic retention time with pure standards, detection of at least two selected reaction monitoring MS/MS transitions, and correct abundance ratio between the monitored product ions. Deuterated internal standards were constantly used, whenever commercially available.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

We first examined descriptive statistics and determined the extent of overlap between self-reported drug use and positive hair results. Chi-square and Fisher’s Exact Test were used to determine whether key covariates were associated with a positive hair sample for 1) MDMA, 2) methylone, and 3) butylone. We also examined whether any covariates were related to reporting no lifetime use of synthetic cathinones (or other stimulant NPS or unknown pills or powder) and having a positive test result for one of these drugs. We took a conservative approach, only considering a participant to have a discrepant report if he or she did not report lifetime use of any listed “bath salt”, stimulant NPS, or unknown pill or powder. However, we did not consider reports discrepant if a participant reported use of other drugs such as NBOMe, ketamine, cocaine, or methamphetamine.

3. RESULTS

Of the 48 participants that reported lifetime ecstasy use and provided a hair sample that was analyzable, the majority (70.8%, n = 34) reported no lifetime use of “bath salts”, stimulant NPS, or unknown pills or powders. Seven participants (14.6% of the sample) reported lifetime use of “bath salts” (including one that also reported lifetime use of unknown pills or powders), and of these, three reported using “bath salts unknown”, one reported use of ethcathinone, one reported use of methcathinone, and three reported use of methylone. No participants reported use of other stimulant NPS, and 8 participants (16.7%) reported lifetime use of unknown pills or powders (one of whom also reported “bath salt” use).

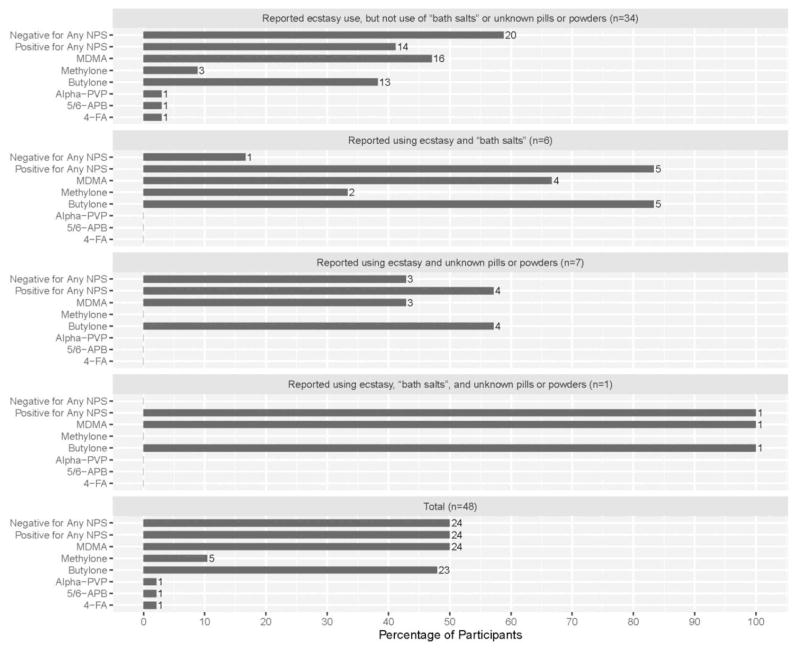

Of the 34 participants that reported no lifetime use of “bath salts”, stimulant NPS, or unknown pills or powders, 41.2% (n = 14) tested positive for an NPS (Figure 1). Half (50.0%, n = 24) of the sample had MDMA detected in their hair. Half (50.0%, n = 24) had at least one NPS detected in their hair (not mutually exclusive from those who tested positive for MDMA), and all but one hair sample that tested positive for NPS contained butylone (47.9%; n = 23; alone or in combination with other NPS). A tenth (10.4%) of the sample had methylone detected in their hair, and alpha-PVP, 5/6-APB, and 4-FA were each detected once (in samples from different participants). Two-thirds (66.6%) of hair samples testing positive for MDMA also tested positive for butylone. Table 1 further presents combinations of MDMA and NPS detected. With exception of MXE, none of the other analytes considered in the analytical method were identified in any of the analyzed samples. Although beyond the scope of our analyses, it should be noted that four participants (who also tested positive for butylone) tested positive for MXE (a common ketamine replacement); however, all four of these cases reported ketamine use, three of which also reported use of 2-MeO-ketamine and one specifically reported using MXE.

Figure 1.

Hair Test Results According to Self-Reported Lifetime Drug Use among Self-Reported Ecstasy Users that Provided a Hair Sample (N = 48) from a Larger Study

Table 1.

Combinations of Hair Test Results According to Self-Reported Lifetime Drug Use among Self-Reported Ecstasy Users that Provided a Hair Sample (N = 48) from a Larger Study

| Drug Detected | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| None | 17 | 35.4 |

| MDMA | 7 | 14.6 |

| Butylone | 7 | 14.6 |

| MDMA + butylone | 10 | 20.8 |

| MDMA + butylone + methylone | 4 | 8.3 |

| MDMA + butylone + methylone + alpha-PVP | 1 | 2.1 |

| MDMA + 5/6-APB | 1 | 2.1 |

| MDMA + 4-FA | 1 | 2.1 |

Table 2 presents percentages of drug report discrepancies and positive test results according to sample characteristics. Racial minorities (non-whites) were more likely to report no lifetime “bath salt” use or no use of other drugs we tested, but have a positive hair sample (p = .011), and racial minorities were also more likely to have butylone detected in their hair (p = .007). Those who reported no use of “bath salts”, stimulant NPS, or unknown pills or powders, but tested positive for an NPS, were more likely to report having earned less than a Bachelor’s degree (p = .026). Frequent nightclub/festival attendance was the strongest and most consistent predictor as it was related to having one’s hair test positive for MDMA (p < .001), butylone (p = .028), and methylone (p = .001), and frequent attendance approached significance with regard to reporting no lifetime use of other drugs, but having a positive detection of use via hair sample (p = .071).

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics According to Hair Test Results and Discrepant Reporting among Self-Reported Ecstasy Users that Provided a Hair Sample (N = 48) from a Larger Study

| Full Sample % | Discordant Report % | Positive for MDMA % | Positive for Butylone % | Positive for Methylone % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | -- | 41.2 | 50.0 | 47.9 | 10.4 |

|

| |||||

| Age | |||||

|

| |||||

| 18–20 | 20.8 | 14.3 | 12.5 | 17.4 | 20.0 |

|

| |||||

| 21–22 | 39.6 | 50.0 | 33.3 | 43.5 | 40.0 |

|

| |||||

| 23–25 | 39.6 | 35.7 | 54.2 | 39.1 | 40.0 |

|

| |||||

| Sex | |||||

|

| |||||

| Male | 64.6 | 64.3 | 66.7 | 56.6 | 60.0 |

|

| |||||

| Female | 35.4 | 35.7 | 33.3 | 43.5 | 40.0 |

|

| |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

|

| |||||

| Non-White | 41.7 | 71.4* | 45.8 | 60.9* | 60.0 |

|

| |||||

| White | 58.3 | 28.6 | 54.2 | 39.1 | 40.0 |

|

| |||||

| Educational Attainment | |||||

|

| |||||

| Less than a Bachelor’s Degree | 60.4 | 85.7* | 58.3 | 73.9 | 100.0 |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 39.6 | 14.3 | 41.7 | 26.1 | 0.0 |

| Weekly Income | |||||

|

| |||||

| <$500 | 52.1 | 28.6 | 50.0 | 52.2 | 40.0 |

| ≥$500 | 47.9 | 71.4 | 50.0 | 47.8 | 60.0 |

|

| |||||

| Recruitment Venue | |||||

|

| |||||

| Nightclub | 85.4 | 78.6 | 91.7 | 87.0 | 100.0 |

|

| |||||

| Festival | 14.6 | 21.4 | 8.3 | 13.0 | 0.0 |

| Nightclub Attendance | |||||

| Less Than Once a Week | 62.5 | 42.9 | 33.3*** | 47.8* | 0.0** |

| At Least Once a Week | 37.5 | 57.1 | 66.7 | 52.2 | 100.0 |

| Type(s) of Ecstasy Used | |||||

| Used Pills, Powder, and Crystal | 57.4 | 64.3 | 56.5 | 52.2 | 60.0 |

| Used Only One or Two Types | 42.6 | 35.7 | 43.5 | 47.8 | 40.0 |

| Suspect Ecstasy Adulteration | |||||

| No or Not Sure | 45.7 | 64.3 | 34.8 | 47.8 | 60.0 |

| Yes | 54.3 | 35.7 | 65.2 | 52.2 | 40.0 |

Note. “Discordant report” refers to when a participant’s hair tested positive for other drug(s), but he or she only reported ecstasy use. Due to small sample size we were not able to implement a statistical correction for multiple testing.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

4. DISCUSSION

Ecstasy is among the most popular party drugs in the nightclub and dance festival scenes. Rates of poisonings related to use have increased in the US, and this may be due, in part, to users unknowingly using NPS such as synthetic cathinones in their ecstasy. In this study, we sought to determine whether nightclub/festival attendees who reported ecstasy use were unknowingly using NPS such as synthetic cathinones. Among this sample of nightclub/festival-attending young adults in NYC who reported lifetime ecstasy/MDMA/Molly use, almost half provided hair samples that were positive for butylone, and a tenth provided hair samples that were positive for methylone. However, among those who reported no lifetime use of “bath salts”, stimulant NPS, or unknown powders or pills, about four out of ten had a positive test result for an NPS we tested. While we cannot completely rule out dishonest responses (e.g., underreporting “bath salt” use), our results suggest that many ecstasy users are unintentionally or unknowingly using synthetic cathinones and/or other NPS. Surely, the time frame represented by hair testing cannot adequately test for overall lifetime use. Nevertheless, due to the variability of the analyzed hair length and the normal hair rate growth, the exposure to “bath salts” and/or other NPS may have occurred up to one year earlier. We could not confirm that these drugs were in (or sold as) the ecstasy these participants reported taking, but results do suggest that ecstasy users are at high risk for unknowingly using such drugs—whether or not this unintentional use was directly associated with ecstasy use.

A recent study focusing on a national sample of high school seniors in the US found that only 1% self-reported last-year use of “bath salts” (Palamar, 2015), and an investigation of the same national sample found that those who attend “rave” parties—especially at higher frequencies—are more likely to report “bath salt” use (Palamar et al., 2015a). Specifically, results from that study suggest that 3.7% of those ever attending a “rave” reported “bath salt” use; 6.7% of those who reported attending monthly or more often reported use, and 1.4% of those ever attending reported using “bath salts” on six or more occasions (Palamar et al., 2015a). Findings from this current study corroborate these national survey findings in that nightclub/festival attendance was associated with a higher likelihood of having a positive test result for synthetic cathinones. Frequent attendance was also linked to ecstasy users not knowing they have used synthetic cathinones. We also found that participants who are racial minorities or who reported education lower than a Bachelor’s degree were more likely to unknowingly use synthetic cathinones. Since racial minority status and level of education are often indicators of socioeconomic status, more research is needed to determine whether use is dependent on price or availability of unadulterated MDMA.

While ecstasy users are at high risk for using synthetic cathinones and other NPS (Bruno et al., 2012; Palamar et al., 2015b; Winstock et al., 2011), we currently do not know the extent of unintentional use in the nightclub/festival scenes. Currently, most national statistics focus on self-reported use of drugs so many poisonings related to “ecstasy” use may in fact be related to unintentional NPS use. This is among the first studies to compare self-reported ecstasy and NPS use to test results of biological hair samples. More studies are needed to adequately determine the extent to which ecstasy users are unknowingly using synthetic cathinones or other NPS.

4.1. Limitations

We were only able to obtain hair samples from a quarter of participants who took the survey. For many participants, the collected amount of hair was too small to be analyzed because it was difficult for trained recruiters to collect adequate samples in dark areas outside of nightclubs at night. However, we confirmed that there were no systematic differences by any covariate regarding who provided a hair sample, so we believe there was little to no bias. We do recommend that similar studies allow for collection of body hair as a potential alternative for participants (primarily males) who have little to no hair on their heads. Results from this study were derived from a relatively small analytic sample; however, the subsample was selected from a larger epidemiology study that utilized time-space sampling (a form of probability-based sampling). Despite low power due to a relatively small cohort, we were still able to detect multiple significant differences along covariates.

We only assessed self-reported lifetime use of drugs, which limited our ability to determine recency or frequency of use, and we were only able to test for select NPS. Therefore, it is possible that some participants (knowingly or unknowingly) used synthetic cathinones or other NPS that we were not able to test for. Finally, we took a conservative approach, only coding participants as providing discordant responses if they reported no lifetime use of “bath salts”, stimulant NPS, or unknown pills or powders. Thus, the percentage of discordant responses (41.2%) is likely an underestimate. However, among the 14 that reported no lifetime use of any of these NPS, many reported lifetime use of illicit drugs that commonly come in powder form, and thus do have the potential to be adulterated with NPS such as “bath salts”. Specifically, 10 reported lifetime cocaine use, 3 reported lifetime methamphetamine use, and 10 reported lifetime ketamine and/or 2-MeO-ketamine use. Drugs such as ketamine, however, are more likely to be adulterated with dissociative NPS; for example, we did detect MXE in four samples, but in participants who reported using ketamine and/or 2-MeO-ketamine (with only one specifically reporting MXE use). While we were unable to determine whether positive NPS tests results are due to ecstasy use, we did find that ecstasy users are at risk for unintentional use of NPS.

Basic drugs, including most amphetamines and cathinones, are expected to bind to eumelanin via hydrogen bonds and charge-transfer interactions, possibly resulting in partly biased quantitative results that depend on the hair color of the donors (Cooper, 2015). This alleged effect has been frequently addressed to justify differences observed among ethnic groups. However, the experimental studies have been somehow contradictory and the overlapping of other influencing factors prevented any definite conclusion on this point (Vincenti and Kintz, 2015).

4.2. Conclusions

We found that about four out of ten nightclub/festival-attending young adult ecstasy users tested positive for “bath salts” and/or other NPS, despite reporting no lifetime use of these substances. Results suggest that many ecstasy-using nightclub/festival attendees may be unintentionally using “bath salts” or other NPS. Prevention and harm reduction education is needed for this population—especially among frequent attendees. In addition, seized ecstasy/Molly should be more extensively tested (e.g., by the DEA) for contents/adulterants in order to more effectively monitor the drug market, and “drug checking” (e.g., pill testing) by users may be beneficial for those rejecting abstinence.

Highlights.

We tested hair samples from ecstasy users for novel psychoactive substances (NPS)

Almost half had hair test positive for butylone and 10% tested positive for methylone

NPS were detected in 41.2% of those reporting no use

Racial minorities were more likely to test positive for butylone or other NPS

Drug testing is needed for those who reject abstinence and use ecstasy

Acknowledgments

Role of funding source

This pilot study was funded by the Center for Drug Use and HIV Research (CDUHR – P30 DA011041). J. Palamar is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (NIDA K01DA-038800).

Footnotes

Contributors

All authors are responsible for this reported research. J. Palamar conceptualized and designed the study, and conducted the statistical analyses. C. Cleland mentored and assisted J. Palamar with regard to study design, time-space sampling, and statistical analysis. A. Salomone and M. Vincenti conducted the hair analyses via UHPLC-MS/MS methods and quantified the biological findings. All authors drafted the initial manuscript, interpreted results, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Association of Poison Control Centers. [accessed 12.16.15];Bath Salts. 2015 ( http://www.aapcc.org/alerts/bath-salts/)

- Baggott M, Heifets B, Jones RT, Mendelson J, Sferios E, Zehnder J. Chemical analysis of ecstasy pills. JAMA. 2000;284:2190. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.17.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Jr, Green JL, Rumack BH, Giffin SL. 2009 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 27th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol. 2010;48:979–1178. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2010.543906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno R, Matthews AJ, Dunn M, Alati R, McIlwraith F, Hickey S, Burns L, Sindicich N. Emerging psychoactive substance use among regular ecstasy users in Australia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunt TM, Poortman A, Niesink RJ, van den Brink W. Instability of the ecstasy market and a new kid on the block: mephedrone. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:1543–1547. doi: 10.1177/0269881110378370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carhart-Harris RL, King LA, Nutt DJ. A web-based survey on mephedrone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;118:19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudevilla-Gálligo F, Ventura M, Indave Ruiz BI, Fornís I. Presence and composition of cathinone derivatives in drug samples taken from a drug test service in Spain (2010–2012) Hum Psychopharmacol. 2013;28:341–344. doi: 10.1002/hup.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper GAA. Anatomy and physiology of hair, and principles for its collection. In: Kintz P, Salomone A, Vincenti M, editors. Hair Analysis in Clinical and Forensic Toxicology. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2015. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Di Corcia D, D’Urso F, Gerace E, Salomone A, Vincenti M. Simultaneous determination in hair of multiclass drugs of abuse (including THC) by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2012;899:154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. An update from the EU Early Warning System (March 2015) Publications Office of the European Union; Luxembourg: 2015. [accessed 12.16.15]. New psychoactive substances in Europe. ( http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_235958_EN_TD0415135ENN.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Hall AP, Henry JA. Acute toxic effects of ‘Ecstasy’ (MDMA) and related compounds: overview of pathophysiology and clinical management. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:678–685. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitány-Fövény M, Kertész M, Winstock A, Deluca P, Corazza O, Farkas J, Zacher G, Urbán R, Demetrovics Z. Substitutional potential of mephedrone: an analysis of the subjective effects. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2013;28:308–316. doi: 10.1002/hup.2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BC, Parsons JT, Wells BE. Prevalence and predictors of club drug use among club-going young adults in New York City. J Urban Health. 2006;83:884–895. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9057-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kintz P. Issues about axial diffusion during segmental hair analysis. Ther Drug Monit. 2013;35:408–410. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e318285d5fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendoiro E, Jiménez-Morigosa C, Cruz A, López-Rivadulla M, de Castro A. O20: Hair analysis of amphetamine-type stimulant drugs (ATS), including synthetic cathinones and piperazines, by LC-MSMS. Toxicol Anal Clin. 2014;26:S13. doi: 10.1002/dta.1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick J. Recreational bupropion abuse in a teenager. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;53:214. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring The Future National Survey Results On Drug Use, 1975–2014: Volume I, Secondary School Students. Institute for Social Research: University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 2015. [accessed 12.16.15]. ( http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol1_2014.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Miotto K, Striebel J, Chob AK, Wanga C. Clinical and pharmacological aspects of bath salt use: a review of the literature and case reports. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Jr, McMillan N, Ford M. 2013 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 31st Annual Report. Clin Toxicol. 2014;52:1032–1283. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2014.987397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ. “Bath salt” use among a nationally representative sample of high school seniors in the United States. Am J Addict. 2015;24:488–491. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Griffin-Tomas M, Ompad DC. Illicit drug use among rave attendees in a nationally representative sample of US high school seniors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015a;152:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Martins SS, Su MK, Ompad DC. Self-reported use of novel psychoactive substances in a US nationally representative survey: prevalence, correlates, and a call for new survey methods to prevent underreporting. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015b;156:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AC. Is ecstasy MDMA? A review of the proportion of ecstasy tablets containing MDMA, their dosage levels, and the changing perceptions of purity. J Psychopharmacol. 2004;173:234–241. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1712-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AC. Human psychobiology of MDMA or ‘ecstasy’: an overview of 25 years of empirical research. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2013;28:289–307. doi: 10.1002/hup.2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridpath A, Driver CR, Nolan ML, Karpati A, Kass D, et al. Illnesses and deaths among persons attending an electronic dance-music festival - New York City, 2013. MMWR. 2014;63:1195–1198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Mattison AM, Franklin DR., Jr Club drugs and sex on drugs are associated with different motivations for gay circuit party attendance in men. Subst Use Misuse. 2003;38:1173–1183. doi: 10.1081/ja-120017657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust KY, Baumgartner MR, Dally AM, Kraemer T. Prevalence of new psychoactive substances: a retrospective study in hair. Drug Test Anal. 2012;4:402–408. doi: 10.1002/dta.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomone A, Gazzilli G, Di Corcia D, Gerace E, Vincenti M. Determination of cathinones and other stimulant, psychedelic and dissociative designer drugs in real hair samples. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00216-015-9247-4. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Ecstasy-Related Emergency Department Visits by Young People Increased between 2005 and 2011. [accessed 12.16.15];Alcohol Involvement Remains a Concern. 2013a ( http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/spot127-youth-ecstasy-2013/spot127-youth-ecstasy-2013.pdf)

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. “Bath Salts” Were Involved in Over 20,000 Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits in 2011. [accessed 12.16.15];The DAWN Report Data Spotlight, Drug Abuse Warning Network. 2013b ( http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/spot117-bath-salts-2013/spot117-bath-salts-2013.pdf)

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2014. [accessed 12.16.15]. NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863. ( http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHmhfr2013/NSDUHmhfr2013.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Tanner-Smith EE. Pharmacological content of tablets sold as “ecstasy”: results from an online testing service. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Drug Enforcement Administration, Office of Diversion Control. [accessed 12.16.15];National Forensic Laboratory Information System: Year 2014 Report. 2015 ( https://www.nflis.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/DesktopModules/ReportDownloads/Reports/NFLIS2014AR.pdf)

- Vincenti M, Kintz P. New challenges and perspectives in hair analysis. In: Kintz P, Salomone A, Vincenti M, editors. Hair Analysis in Clinical and Forensic Toxicology. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2015. pp. 337–368. [Google Scholar]

- Vogels N, Brunt TM, Rigter S, van Dijk P, Vervaeke H, Niesink RJ. Content of ecstasy in the Netherlands: 1993–2008. Addiction. 2009;104:2057–2066. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstock AR, Mitcheson LR, Deluca P, Davey Z, Corazza O, Schifano F. Mephedrone, new kid for the chop? Addiction. 2011;106:154–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood DM, Stribley V, Dargan PI, Davies S, Holt DW, Ramsey J. Variability in the 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine content of ‘ecstasy’ tablets in the UK. Emerg Med J. 2011;28:764–765. doi: 10.1136/emj.2010.092270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawilska JB, Andrzejczak D. Next generation of novel psychoactive substances on the horizon - a complex problem to face. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;157:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawilska JB, Wojcieszak J. Designer cathinones—an emerging class of novel recreational drugs Forensic Sci. Int. 2013;231:42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]