Abstract

Background

Use of intensive care after major surgical procedures, and whether routinely admitting patients to intensive care units (ICUs) improves outcomes or increases costs is unknown.

Methods

We examined frequency of admission to an ICU during the hospital stay for Medicare beneficiaries undergoing selected major surgical procedures: elective endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (endovascular AAA), cystectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), esophagectomy, and elective open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (open AAA). We compared hospital mortality, length of stay and Medicare payments for patients receiving each procedure in hospitals admitting patients to the ICU <50% of the time (low use), 50-89% (moderate use), and ≥90% (high use), adjusting for patient and hospital factors.

Results

The cohort ranged from 7,878 patients in 162 hospitals for esophagectomies to 69,989 patients in 866 hospitals for endovascular AAA. Overall admission to ICU ranged from 35.6% (endovascular AAA) to 71.3% (open AAA). Admission to ICU across hospitals ranged from <5% to 100% of patients for each surgical procedure. There was no association between hospital use of intensive care and mortality for any of the five surgical procedures. There was a consistent association between high use of intensive care with longer length of hospital stay and higher Medicare payments only for endovascular AAA.

Conclusions

There is little consensus regarding the need for intensive care for patients undergoing major surgical procedures and no relationship between a hospital's use of intensive care and hospital mortality. There is also no clear relationship between use of intensive care and either length of hospital stay or payments for care.

Keywords: Intensive Care Unit, Triage, Surgery, Mortality, Length of Stay

Millions of major surgical procedures are performed every year around the world,1,2 and improving peri-operative outcomes involves identification of best practices.3 Recent data from Europe found higher than expected hospital mortality (4%) for patients undergoing surgery, with substantial variation in mortality across countries even after adjustment for patient factors and complexity of the surgery.1 Only 5% of all patients received intensive care and a substantial proportion of the patients who died (70%) were never admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU), raising the question of whether more aggressive use of intensive care services may improve post-operative care and outcomes for patients at high risk of death after surgery.4 However, observational studies are limited in the ability to assess the benefits of intensive care because patients selected for admission to ICU are inherently sicker and have higher mortality than patients who are not admitted to the ICU, thus creating large biases in populations to be compared.5 A number of studies have examined high intensity interventions, such as inotropic support,6,7 for which the use of intensive care might optimize outcomes; but, none has addressed the specific use of intensive care for surgical patients.8 Therefore, the assumption that greater rates of admission to an ICU may reduce morbidity and mortality in the surgical patient population is reasonable, but unproven.8-10

Care in ICUs is substantially more expensive than that on general hospital wards, and represents a limited resource.11,12 Determining whether high quality post-operative care should include routine use of intensive care has large ramifications for peri-operative quality improvement initiatives, as well as the potential costs of care. We sought first to assess variation in use of intensive care after a range of major surgical procedures to determine whether there is agreement across hospitals regarding the need for intensive care services. Second, we sought to determine whether use of intensive care services at the hospital level is associated with hospital mortality, length of hospital stay, or Medicare payments for patients undergoing major surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This research involved secondary analyses of de-identified data and was deemed not human subjects research by the Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board, New York, NY, USA. We performed a retrospective study using five years of the MedPAR file from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. This dataset contains data on all Medicare hospitalizations from 2004 through 2008, linked with data from the American Hospital Association annual survey from 2007.13

Patients and variables

Medicare provides health insurance for Americans aged 65 and older who have worked and paid into the system. It also provides health insurance to selected younger people with disabilities, end stage renal disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. We included all patients 65 years or older undergoing five select surgical procedures during a hospitalization, and excluded Medicare beneficiaries under age 65 since they represent a highly selected group of individuals with specific diagnoses, as previously described.13 The procedures were: elective endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm (endovascular AAA), cystectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), esophagectomy, and elective open repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (open AAA). We chose these surgical procedures from a larger list of possible procedures after initial inspection of the data because they are 1) commonly performed in patients over the age of 65, 2) well circumscribed and usually not associated with another surgery, and 3) associated with a range of different hospital mortality rates (see Supplemental Digital Content Table 1, listing individual ICD-9-CM and procedure codes used).

We defined ICU admission using critical care-specific resource utilization codes, including intensive care and/or coronary care. We could not confirm whether intensive care admission definitely occurred after a surgical procedure, rather than before. Therefore, we refer to patients as having received intensive care during the hospitalization. We also could not assess whether an ICU admission was planned or occurred on an emergent basis as a “rescue” therapy.

Statistics

We excluded patients cared for in any hospital that performed the procedure in Medicare beneficiaries less than 20 times over five years or did not have information on the availability of ICU beds or number of hospital beds (Supplemental Digital Content Figure 1). Of note, the exclusions were performed separately for each surgical procedure so that a hospital could be included in the analysis of some or all surgical procedures.

Hospital and patient characteristics

We summarized hospital and patient characteristics and outcomes for each surgical procedure, using percentages, means with standard deviations (±SD), and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), as appropriate. We then summarized the frequency of admission to an ICU for each surgical procedure overall, and by individual hospital. These data have been published previously.13

For each surgical procedure we categorized hospitals as admitting patients to the ICU 0-49% of the time (low use), 50-89% (moderate use), or ≥90% (high use). We chose not to use percentiles, as we wished to ensure clinically meaningful differences in use of intensive care between groups, and the cut-offs for percentiles would have shifted depending on the surgical procedure. We next summarized patient characteristics for patients who received each surgical procedure, stratified by hospital ICU use.

Outcomes

Outcomes included hospital mortality, hospital length of stay and total Medicare payments, as defined by the total hospital charges covered by Medicare, with all payments reported in 2008 dollars using an inflation correction.14 Our first objective was to describe the degree of variation in use of intensive care services for different surgical procedures. Our second objective was to assess hospital-level outcomes for patients cared for in high vs. low use hospitals. We assessed unadjusted differences using chi-squared, t-test and Spearman's rank correlation, as appropriate. For adjusted analyses, we adjusted for patient and hospital-level characteristics using multi-level modeling, with clustering by hospital. We assessed the association with hospital length of stay and Medicare payments using multi-level linear regression. Data on length of stay variables were log transformed due to their skewed nature. Costs were assessed using means.15 We report results as either odds ratios, or regression coefficients. Because of unexpected findings regarding Medicare payments, we post hoc examined the mean Medicare payments for patients in high vs. low ICU use hospitals stratified by whether or not patients went to the ICU. We assessed differences between groups using Analysis of Variance.

Our secondary analysis included assessment of outcomes for individual patients using multi-level modeling, clustering on hospital, and propensity-based matched analyses to determine whether we found the same associations between use of intensive care and outcomes. All available patient- and hospital-level independent variables were included in each final multivariate model and the model to create propensity scores. Propensity matching was performed to match patients who did or did not receive intensive care based on their likelihood (propensity) to receive intensive care. After randomly ordering patients, we used the ‘psmatch2’ algorithm in STATA 11.1 with one-to-one nearest-neighbor matching without replacement and with maximal caliper distance of 25% of the standard deviation of all propensity scores.16 Additionally, exact matching was used for each covariate for which the propensity score did not achieve appropriate balance; cystectomy: 3,962 pairs with imbalance in gender, comorbidity index, weekend admission, and hospital procedure volume; PD: 1,103 pairs with imbalance in age and race; Esophagectomy: 1,742 pairs with imbalance in weekend admission and age; Open AAA: 3,673 pairs with imbalance in gender, comorbidity index, weekend admission, age, and race. We assessed differences in hospital mortality between propensity matched patients using logistic regression.

We conducted analyses in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA), Stata 11.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA), and SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Carey, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Cohort characteristics

After exclusions (See Supplemental Digital Content Figure 1, flowchart of exclusions), the number of patients receiving each surgical procedure varied from 9,805 patients in 156 hospitals for PD up to 69,989 patients in 866 hospitals for endovascular AAA (Tables 1 and 2). The majority of hospitals performing these surgical procedures were categorized as teaching hospitals (Table 1). Most were hospitals with over 400 beds, and most hospitals had more than 7.5% of their beds designated as ICU beds (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of hospitals performing each surgical procedure over five years. Hospital characteristics data are from the AHA. Number of surgeries annually is defined by the number of patients undergoing surgery who stay overnight in the hospital

| Procedures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endo AAA | Cystectomy | PD | Esophagectomy | Open AAA | |

| # of hospitals in cohort, n | 866 | 254 | 156 | 162 | 549 |

| Academic status, n (%) | |||||

| non-teaching | 329 (38.0) | 39 (15.4) | 7 (4.5) | 13 (8.0) | 183 (33.3) |

| teaching | 537 (62.0) | 215 (84.7) | 149 (95.5) | 149 (92.0) | 366 (66.7) |

| Hospital beds, n (%) | |||||

| <200 | 126 (14.6) | 15 (5.9) | 6 (3.9) | 7 (4.3) | 47 (8.6) |

| 200-399 | 426 (49.2) | 60 (23.6) | 24 (15.4) | 22 (13.6) | 245 (44.6) |

| 400-599 | 197 (22.8) | 96 (37.8) | 53 (34.0) | 58 (35.8) | 152 (27.7) |

| 600-799 | 78 (9.0) | 48 (18.9) | 45 (28.9) | 43 (26.5) | 68 (12.4) |

| 800-999 | 23 (2.7) | 21 (8.3) | 17 (10.9) | 20 (12.4) | 23 (4.2) |

| 1000+ | 16 (1.9) | 14 (5.5) | 11 (7.1) | 12 (7.4) | 14 (2.6) |

| Average daily census, median (IQR) | 230 (161-351) | 376 (270-519) | 446 (319-603) | 429 (329-604) | 272 (183-417) |

| Number of surgeries annually, median (IQR)* | 5,097 (3,405-8,047) | 8,720 (6,196-11,704) | 10,218 (7,392-13,729) | 10,389 (7,472-13,594) | 6,364 (4,238-9,201) |

| Percentage of hospital beds designated as ICU beds n (%) | |||||

| <2.5% | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| 2.5-4.9% | 28 (3.2) | 13 (5.1) | 6 (3.9) | 6 (3.7) | 20 (3.6) |

| 5-<7.4% | 181 (20.9) | 49 (19.3) | 24 (15.4) | 25 (15.4) | 100 (18.2) |

| 7.5-9.9% | 300 (34.6) | 88 (34.7) | 62 (39.7) | 57 (35.2) | 191 (34.8) |

| 10-12.4% | 180 (20.8) | 49 (19.3) | 30 (19.2) | 36 (22.2) | 110 (20.0) |

| 12.5-14.9% | 94 (10.9) | 31 (12.2) | 20 (12.8) | 23 (14.2) | 68 (12.4) |

| ≥15% | 82 (9.5) | 24 (9.5) | 14 (9.0) | 15 (9.3) | 59 (10.8) |

| Trauma Center | |||||

| no | 389 (45.0) | 75 (29.5) | 40 (25.6) | 45 (27.8) | 217 (39.5) |

| yes | 476 (55.0) | 179 (70.5) | 116 (74.4) | 117 (72.2) | 332 (60.5) |

AAA = abdominal aortic aneurysm; ICU = intensive care unit; IQR = interquartile range; PD = pancreaticoduodenectomy

Table 2.

Frequency of surgical procedures performed on Medicare beneficiaries, outcomes and resource use

| For patients in all hospitals | By individual hospital | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | # of hospitals (n) | Overall admission to ICU (%) | Overall hospital mortality (%) | 1 or more complications (%) | Hospital length of stay (days) median, IQR | Medicare payments per patient (thousands of US dollars) mean (SD) | Median volume of surgical cases | Median ICU admission rate (%) | Range of ICU admission rates (%) | |

| Endovascular AAA | 69989 | 866 | 35.6 | 1.0 | 12.1 | 2 (1-4) | $76.1 (54.7) | 56.0 | 52.6 | 0.0-100.0 |

| Cystectomy | 13779 | 254 | 44.5 | 2.5 | 23.1 | 9 (7-13) | $86.0 (85.0) | 35.0 | 50.0 | 3.9-100.0 |

| PD | 9805 | 156 | 59.3 | 4.0 | 30.2 | 11 (8-18) | $117.4 (138.6) | 43.5 | 71.4 | 0.0-100.0 |

| Esophagectomy | 7878 | 162 | 65.1 | 6.9 | 43.7 | 12 (9-20) | $156.2 (214.3) | 36.0 | 80.0 | 3.6-100.0 |

| Open AAA | 27776 | 549 | 71.3 | 4.8 | 31.0 | 7 (6-11) | $84.6 (98.5) | 38.0 | 92.0 | 0.0-100.0 |

AAA = abdominal aortic aneurysm; ICU = intensive care unit; IQR = interquartile range; PD = pancreaticoduodenectomy; SD = standard deviation

The overall admission rate to ICU ranged from 35.6% of patients undergoing endovascular AAA up to 71.3% of patients undergoing open AAA (Table 2). Hospital mortality rates ranged from 1.0% for endovascular AAA up to 6.9% for esophagectomy. The percentage of patients with one or more complications was lowest for endovascular AAA (12.1%) and highest for esophagectomy (43.7%). Median hospital length of stay and costs of care were similarly lowest for endovascular AAA and highest for esophagectomy (see Supplemental Digital Content Table 2 for detailed characteristics of patients undergoing each surgical procedure).

Variation in use of intensive care

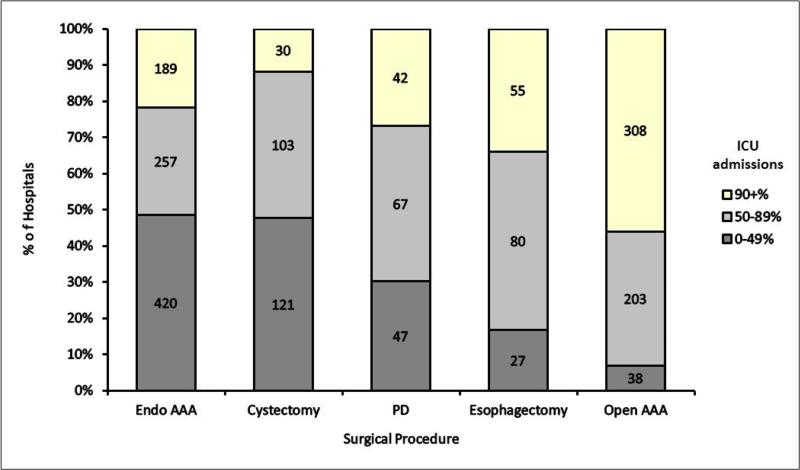

Use of intensive care varied markedly across hospitals. Overall use of intensive care ranged from 0% to 100% of admissions in each hospital undergoing endovascular AAA, PD, and open AAA, and 3.6% to 100% and 3.9% to 100% of admissions in each hospital for esophagectomy and cystectomy respectively (Table 2). There were a substantial number of hospitals in the low (0-49%), medium (50-89%), and high (≥90%) use categories for each surgical procedure (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of use of critical care across hospitals for patients undergoing five major surgical procedures

Abbreviations: AAA = abdominal aortic aneurysm; ICU = intensive care unit; PD = pancreaticoduodenectomy

We examined characteristics for patients who underwent each surgical procedure, stratified by their care in a hospital with low, medium or high use of intensive care for the specific surgical procedure. There were a few differences in the distributions of age, or race for patients cared for in hospitals with high versus low use of intensive care (See Supplemental Digital Content Tables 3-7 showing patient characteristics for each procedure, stratified by hospital ICU use). Of particular note, the number of patients with 2+ Charlson comorbidities was not substantially higher in the high use hospitals compared with the low use hospitals for any of the surgical procedures: 52.5% vs 51.0% for endovascular AAA; 17.0% vs 18.1% for cystectomy; 22.2% vs 22.2% for PD; 14.9% vs 16.0% for esophagectomy; 51.4% vs 49.3% for open AAA.

Hospital Mortality

Individual patient admission to intensive care was associated with a substantially increased risk of hospital death, as assessed by both multi-level multivariable logistic regression and propensity matching of patients for the likelihood of admission to ICU (Table 3). We then assessed outcomes for patients based on their care in a hospital with high, medium, or low use of intensive care for the specific surgical procedure. In unadjusted analysis there was no association between mortality for patients cared for in hospitals belonging to a high versus low ICU admission group for endovascular AAA (1.1% vs 1.0% P=0.54), cystectomy (2.8% vs 2.3% P=0.31), PD (3.7% vs 3.3% P=0.36) or open AAA (4.6% vs 4.3% p=0.51), but there was a significantly increased hospital mortality for patients undergoing esophagectomies in hospitals with high ICU use versus low use (7.5% vs 5.4% P=0.007) (Table 4). After multivariable adjustment, there was no association for any surgical procedure between hospital mortality and care in a high versus low-ICU use hospital (Table 5; for the full model with all variables for each surgical procedure, see Supplemental Digital Content Table 8).

Table 3.

Association between use of intensive care and hospital mortality adjusted for patient and hospital factors

| Multivariable adjustment | Propensity matched | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Total (n) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Endovascular AAA | ||||||

| No ICU | 45,973 | Ref | NA | Ref | ||

| ICU | 24,916 | 9.83 (7.88,12.28) | <0.001 | NA | NA | |

| Cystectomy | ||||||

| No ICU | 7,647 | Ref | 3,962 | Ref | ||

| ICU | 6,132 | 6.68 (4.84,9.20) | <0.001 | 3,962 | 6.70 (4.59,9.78) | <0.001 |

| PD | ||||||

| No ICU | 3,991 | Ref | 1,103 | Ref | ||

| ICU | 5,814 | 5.63 (3.97,7.99) | <0.001 | 1,103 | 7.00 (4.07,12.03) | <0.001 |

| Esophagectomy | ||||||

| No ICU | 2,749 | Ref | 1,742 | Ref | ||

| ICU | 5,129 | 4.64 (3.39,6.35) | <0.001 | 1,742 | 4.93 (3.46,7.03) | <0.001 |

| Open AAA | ||||||

| No ICU | 19,804 | Ref | 3,673 | Ref | ||

| ICU | 7,972 | 2.30 (1.87,2.84) | <0.001 | 3,673 | 3.11 (2.43,3.97) | <0.001 |

AAA = abdominal aortic aneurysm; CI = confidence interval; ICU = intensive care unit; NA = model would not converge; PD = pancreaticoduodenectomy; Ref = reference

Table 4.

Association between hospital use of intensive care, hospital mortality, length of stay, and costs of care (unadjusted)

| % of patients admitted to ICU in the hospital | Hospital mortality | Hospital length of stay (days) | Medicare payments (thousands of US dollars) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N (%) | P-Value | Median (IQR) | P-Value | Mean (SD) | P-Value | |

| Endovascular AAA | |||||||

| 0-49% | 43,057 | 438 (1.0) | Ref | 2 (1-3) | Ref | $72.2 (51.2) | Ref |

| 50-89% | 16,232 | 169 (1.0) | 0.80 | 2 (1-4) | <0.001 | $83.8 (60.7) | <0.001 |

| ≥90% | 10,700 | 116 (1.1) | 0.54 | 2 (1-4) | <0.001 | $80.3 (57.4) | <0.001 |

| Cystectomy | |||||||

| 0-49% | 7,401 | 169 (2.3) | Ref | 9 (7-12) | Ref | $80.9 (76.4) | Ref |

| 50-89% | 5,184 | 136 (2.6) | 0.22 | 9 (7-13) | <0.001 | $95.4 (99.5) | <0.001 |

| ≥90% | 1,194 | 33 (2.8) | 0.31 | 9 (8-14) | <0.001 | $76.8 (61.0) | 0.08 |

| PD | |||||||

| 0-49% | 3,419 | 111 (3.3) | Ref | 10 (8-16) | Ref | $105.9 (132.4) | Ref |

| 50-89% | 3,977 | 187 (4.7) | 0.002 | 12 (8-19) | <0.001 | $137.8 (158.8) | <0.001 |

| ≥90% | 2,409 | 89 (3.7) | 0.36 | 12 (9-18) | <0.001 | $100.2 (102.5) | 0.08 |

| Esophagectomy | |||||||

| 0-49% | 1,621 | 87 (5.4) | Ref | 10 (8-17) | Ref | $119.4 (155.4) | Ref |

| 50-89% | 3,786 | 268 (7.1) | 0.02 | 13 (9-21) | <0.001 | $170.1 (250.0) | <0.001 |

| ≥90% | 2,471 | 186 (7.5) | 0.007 | 12 (9-20) | <0.001 | $158.8 (183.6) | <0.001 |

| Open AAA | |||||||

| 0-49% | 1,990 | 85 (4.3) | Ref | 7 (6-11) | Ref | $88.9 (137.0) | Ref |

| 50-89% | 9,725 | 511 (5.3) | 0.07 | 7 (6-11) | 0.66 | $85.1 (96.1) | 0.14 |

| ≥90% | 16,061 | 738 (4.6) | 0.51 | 7 (6-11) | 0.10 | $83.7 (94.1) | 0.03 |

AAA = abdominal aortic aneurysm; ICU = intensive care unit; IQR = interquartile range; PD = pancreaticoduodenectomy; Ref = reference; SD = standard deviation

P-Values for outcomes calculated using chi-squared test for mortality, Spearman rank test for length of stay, and analysis of variance for costs.

Table 5.

Association between hospital use of intensive care and hospital mortality, hospital length of stay, and hospital costs adjusted for patient and hospital factors*

| Hospital Mortality | Hospital LOS | Hospital costs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admissions to ICU | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Regression Coefficient (95% CI) | P-value | Regression Coefficient (95% CI) | P-value |

| Endovascular AAA | ||||||

| 0-49% | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| 50-89% | 1.01 (0.82-1.24) | 0.92 | 0.16 (0.12-0.21) | <0.001 | 0.13 (0.06-0.19) | <0.001 |

| ≥90% | 1.05 (0.82-1.34) | 0.71 | 0.15 (0.09-0.20) | <0.001 | 0.013 (0.06-0.20) | <0.001 |

| Cystectomy | ||||||

| 0-49% | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| 50-89% | 1.07 (0.83-1.39) | 0.59 | 0.02 (−0.02-0.06) | 0.35 | 0.12 (0.02-0.22) | 0.02 |

| ≥90% | 1.02 (0.67-1.56) | 0.93 | 0.07 (0.01-0.14) | 0.02 | 0.08 (−0.07-0.24) | 0.29 |

| PD | ||||||

| 0-49% | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| 50-89% | 1.24 (0.93-1.65) | 0.14 | 0.07 (0.00-0.13) | 0.04 | 0.09 (−0.06-0.24) | 0.22 |

| ≥90% | 0.91 (0.64-1.30) | 0.61 | 0.07 (−0.00-0.14) | 0.07 | −0.01 (−0.19-0.24) | 0.87 |

| Esophagectomy | ||||||

| 0-49% | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| 50-89% | 1.22 (0.87-1.70) | 0.25 | 0.09 (0.02-0.16) | 0.01 | 0.22 (0.03-0.41) | 0.02 |

| ≥90% | 1.25 (0.87-1.79) | 0.24 | 0.05 (−0.02-0.13) | 0.15 | 0.15 (−0.06-0.35) | 0.15 |

| Open AAA | ||||||

| 0-49% | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| 50-89% | 1.18 (0.88-1.58) | 0.27 | −0.02 (−0.08-0.04) | 0.50 | −0.01 (−0.15-0.14) | 0.92 |

| ≥90% | 1.08 (0.82-1.44) | 0.58 | 0.01 (−0.05-0.06) | 0.84 | −0.02 (−0.16-0.12) | 0.79 |

adjusted for patient-level factors: age, gender, race, comorbidities, weekend versus weekday admission; hospital-level factors: academic versus non-academic, number of hospital beds, average daily hospital census, number of surgeries performed annually, percent of hospital beds which were intensive care beds, whether the hospital was a trauma center, and the volume of the given procedure performed.

AAA = abdominal aortic aneurysm; CI = confidence interval; ICU = intensive care unit; IQR = interquartile range; PD = pancreaticoduodenectomy; Ref = reference

Hospital length of stay and hospital costs

In unadjusted analyses, hospital length of stay and Medicare payments were higher in high ICU use hospitals compared with low ICU use hospitals for all procedures (Table 4). However, after multivariable adjustment, hospital length of stay and Medicare payments were greater only for patients who underwent endovascular AAA in hospitals with high admission to ICU versus low admission (Table 5). Patients in low ICU use hospitals who did receive intensive care had substantially higher Medicare payments compared with patients who received ICU care in high use hospitals; this finding was consistent across all surgical procedures (Table 6).

Table 6.

Mean Medicare payments per patient across hospitals with high versus low use of intensive care, stratified by use of intensive care for individual patients

| No ICU | ICU | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of patients admitted to ICU in the hospital | N | Mean Medicare payments (thousands of US dollars) (SD) | P-value* | Mean Medicare payments (thousands of US dollars) (SD) | P-value* |

| Endovascular AAA | |||||

| 0-49% | 43,057 | $66.1 (35.1) | <0.001 | $97.3 (86.4) | <0.001 |

| 50-89% | 16,232 | $78.8 (47.1) | $85.8 (65.3) | ||

| ≥90% | 10,700 | $80.8 (56.6) | $80.2 (57.4) | ||

| Cystectomy | |||||

| 0-49% | 7,401 | $67.3 (48.6) | <0.001 | $121.6 (118.7) | <0.001 |

| 50-89% | 5,184 | $74.6 (57.0) | $104.4 (111.7) | ||

| ≥90% | 1,194 | $48.3 (24.5) | $78.1 (61.8) | ||

| PD | |||||

| 0-49% | 3,419 | $85.3 (66.1) | <0.001 | $166.4 (226.5) | <0.001 |

| 50-89% | 3,977 | $108.6 (96.3) | $148.8 (175.6) | ||

| ≥90% | 2,409 | $79.7 (64.2) | $100.9 (103.5) | ||

| Esophagectomy | |||||

| 0-49% | 1,621 | $84.9 (81.6) | <0.001 | $194.9 (232.6) | <0.001 |

| 50-89% | 3,786 | $112.7 (112.3) | $193.9 (284.9) | ||

| ≥90% | 2,471 | $101.3 (138.5) | $161.7 (185.1) | ||

| Open AAA | |||||

| 0-49% | 1,990 | $69.8 (68.7) | 0.67 | $124.0 (206.8) | <0.001 |

| 50-89% | 9,725 | $71.2 (74.0) | $89.8 (102.0) | ||

| ≥90% | 16,061 | $73.0 (65.9) | $84.1 (94.9) | ||

P-value is for comparison of three ICU admission categories (0-49%, 50-89%, and ≥90% using one-way Analysis of Variance

AAA = abdominal aortic aneurysm; ICU = intensive care unit; IQR = interquartile range; PD = pancreaticoduodenectomy; SD = standard deviation

DISCUSSION

These data demonstrate substantial variation across US hospitals in use of intensive care services for elderly patients receiving major surgery. There was no association between greater use of intensive care at the hospital level and hospital mortality, a finding that was robust when examined across five different surgical procedures that were performed with varying frequency and with variable overall risk of hospital death. There were also no consistent differences in length of hospital stay or Medicare payments associated with systematically more or less use of intensive care. The lack of difference in payments was explained by higher payments for the fewer patients who did receive intensive care in low-using hospitals compared with ICU patients in the high-use hospitals.

A substantial number of hospitals admitted more than 90% of patients to the ICU, even for a surgical procedure (endovascular AAA) with an overall hospital mortality of 1%. This finding of variable, and sometimes aggressive admission of patients to ICU with relatively low predicted risk of death, is similar to the recent observation regarding variation in use of intensive care for medical patients. Wide variability was found for ICU admission for patients with diabetic ketoacidosis – a diagnosis with a risk of hospital death of just 0.7%.17 Similarly, a study from the Veterans Affairs hospitals also found very large variations in admission of “low-risk” medical patients to the ICU from the emergency room, with anywhere from 1.2% to 38.9% of patients with a predicted risk of death of <2% receiving intensive care.18

There are many possible reasons for a lack of association between use of intensive care services and hospital mortality for patients undergoing major surgery. First, greater use of intensive care may actively reduce mortality in higher-risk patients. This would be the case if there was a greater severity of illness in patients cared for in the higher ICU-using hospitals. However, we found no substantial difference in age, or comorbidity profile of the patients in higher-use hospitals. Moreover, our analysis investigating outcomes based on ICU use on the hospital rather than individual patient level removes some of this patient-level confounding. But, it remains possible that the hospitals that use more intensive care may have a higher “rescue” rate for high-risk patients, and the hospitals with lower use of intensive care are experiencing a greater frequency of “failure to rescue” – the concept of taking inappropriate care of patients who develop complications, leading to death.19 Because our data did not include dates of ICU admission, we could not investigate whether ICU use was used more or less often to rescue patients in certain hospitals in our cohort. Other possibilities are that the benefits of intensive care, which include support for specific organ failure, and high nurse to patient ratios, may not be realized until the risk of death for patients is well above the 1-6% seen for patients undergoing these major surgical procedures. Alternatively, it may be that the most important components of high quality post-operative care that are gained in an ICU, such as high nurse to patient ratios,20,21 may be adequately delivered in other settings such as a post-operative recovery room or stepdown unit.

Studies of surgical outcomes in the UK and across Europe found higher than expected mortality and low overall use of intensive care for patients who died.1,10 Such findings raised the question of whether more aggressive use of intensive care for surgical patients might reduce some of the observed excess mortality. Our findings suggest that greater systematic use of intensive care for all patients undergoing a given surgery alone may not improve survival outcome for older surgical patients. However, these data must be placed in the context of overall high availability of intensive care beds in the U.S. in comparison with other countries such as the UK.22 While the most appropriate use of intensive care services may not involve default admission of all patients undergoing major surgical procedures, the ability to admit patients identified as requiring organ support in a timely fashion remains important. Recent data on medical patients in France suggest that delayed admission to ICU of patients deemed in need of intensive care was associated with worse outcomes.5 Therefore, our generalizability to countries, and systems of care, that may be on the lower end of overall availability of intensive care remains limited, and the “benefits” of more frequent use of intensive care services post-operatively remains unexplored in lower resource settings.4

We expected greater use of intensive care services to be associated with both longer hospital length of stay and higher costs, as has been seen for patients undergoing carotid endarterectomies.23,24 Our hypothesis was confirmed for patients undergoing endovascular AAA, but was not consistently seen for any other surgical procedure examined. Our findings are consistent with a similar assessment of patients with pneumonia that found no difference in costs with greater use of intensive care.25 It is also notable that admission to an ICU did not seem to lengthen care time by increasing length of stay, which is also consistent with the data on ICU admission for patients with diabetic ketoacidosis.17 The majority of the Medicare payment is driven by the diagnosis related group of the patient, which itself is driven by the surgical procedure performed. It is possible that other costs, such as the physician billing in Medicare Part B, would be different. We also found that, for hospitals that infrequently admitted patients to the ICU, the average costs for the patients who did require intensive care was very high, suggesting that there is an “averaging” effect that cancels out the potential benefit from providing more care on the wards.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, due to the use of Medicare data, we were limited to examination of patients over the age of 65. It is possible that patterns of care for younger patients after surgery could differ. We were also unable to determine whether admission to ICU occurred before, immediately following, or days after the surgical procedure. However, many of the hospitals with ≥90% use of intensive care admitted 100% of the patients, suggesting a routine or “default” use of intensive care for all patients undergoing the surgical procedure. The fact that we could not assess whether hospitals that used intensive care sparingly (<50% of the time) sent the patients immediately after the surgery, or used the ICU as a “rescue” option for patients who developed complications is a substantial limitation and warrants further investigation using other data sources.19 We also did not have detailed information on severity of illness, limiting the conclusions we can draw from the analysis. Finally the analysis was also limited to the acute hospitalization, and focused on hospital mortality. It is possible that potential benefits from one care model may be evident with longer follow-up.

Our choice of which surgical procedures to include was partly driven by concern for power, as we were limited by the frequency of surgical procedures performed in the dataset. We chose to group hospitals into categories of use of intensive care for three reasons: to provide meaningful cut-offs; to assess the >90% group as a reference for “default” use of intensive care; and to maximize our power for a patient-level analysis. However, for the lower volume procedures, the possibility of a Type II error remains a concern. We recognize that there are many possible approaches to this analysis, including more general linear models and/or distance to hospitals as an instrumental variable.25

Some patients, such as those undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting, are routinely admitted to an ICU after surgery, despite a relatively low risk of death in comparison with most of the surgical procedures we examined. These patients usually require elements of intensive care, such as mechanical ventilation and monitored re-warming, that necessitate admission to ICU. Such patients are also at high risk of events, such as arrhythmias and cardiac tamponade, that must be acted on very quickly to ensure favorable outcomes.26 However, we can only speculate that the routine admission to ICU of these patients has helped to drive down mortality associated with these specific surgical procedures.

Pathways representing optimal post-operative care are complex, and often different for each surgical procedure. As we seek to provide high quality care for surgical patients, these data provide important information that care for patients undergoing major surgical procedures need not necessarily involve frequent use of intensive care services to achieve good outcomes. Such options may have important benefits for other patients who require critical care services in situations where ICU bed availability is limited.27 Importantly, though, cost savings and reductions in length of stay may not run in parallel with a reduction in use of intensive care. Moreover, the care pathways that may need to be in place to ensure appropriate care if an ICU bed is not used remain to be elucidated. Further research is needed to determine the best options for individual patients, with the recognition that care requirements may differ dramatically for different high-risk surgical procedures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Award Number K08AG038477 from the National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD, USA to Hannah Wunsch, award Number K08HS020672 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD, USA to Colin R. Cooke.

Footnotes

This study was performed in the Department of Anesthesiology, Columbia University

Competing Interests: The authors declare no competing interests

References

- 1.Pearse RM, Moreno RP, Bauer P, Pelosi P, Metnitz P, Spies C, Vallet B, Vincent JL, Hoeft A, Rhodes A. Mortality after surgery in Europe: a 7 day cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380:1059–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61148-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bainbridge D, Martin J, Arango M, Cheng D. Perioperative and anaesthetic-related mortality in developed and developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380:1075–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60990-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avidan MS, Kheterpal S. Perioperative mortality in developed and developing countries. Lancet. 2012;380:1038–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wunsch H. Is there a starling curve for intensive care? Chest. 2012;141:1393–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert R, Reignier J, Tournoux-Facon C, Boulain T, Lesieur O, Gissot V, Souday V, Hamrouni M, Chapon C, Gouello JP. Refusal of ICU Admission Due to a Full Unit: Impact on Mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1081–1087. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0729OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamilton MA, Cecconi M, Rhodes A. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the use of preemptive hemodynamic intervention to improve postoperative outcomes in moderate and high-risk surgical patients. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:1392–402. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181eeaae5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearse RM, Belsey JD, Cole JN, Bennett ED. Effect of dopexamine infusion on mortality following major surgery: individual patient data meta-regression analysis of published clinical trials. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1323–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31816a091b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sobol JB, Wunsch H. Triage of high-risk surgical patients for intensive care. Crit Care. 2011;15:217. doi: 10.1186/cc9999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jhanji S, Thomas B, Ely A, Watson D, Hinds CJ, Pearse RM. Mortality and utilisation of critical care resources amongst high-risk surgical patients in a large NHS trust. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:695–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pearse RM, Harrison DA, James P, Watson D, Hinds C, Rhodes A, Grounds RM, Bennett ED. Identification and characterisation of the high-risk surgical population in the United Kingdom. Crit Care. 2006;10:R81. doi: 10.1186/cc4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milbrandt EB, Kersten A, Rahim MT, Dremsizov TT, Clermont G, Cooper LM, Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT. Growth of intensive care unit resource use and its estimated cost in Medicare. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2504–2510. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318183ef84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halpern NA, Pastores SM. Critical care medicine in the United States 2000-2005: an analysis of bed numbers, occupancy rates, payer mix, and costs. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:65–71. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b090d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wunsch H, Gershengorn HB, Guerra C, Rowe J, Li G. Association between age and use of intensive care among surgical Medicare beneficiaries. J Crit Care. 2013;28:597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutierrez B, Culler SD, Freund DA. Does hospital procedure-specific volume affect treatment costs? A national study of knee replacement surgery. Health Serv Res. 1998;33:489–511. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson SG, Barber JA. How should cost data in pragmatic randomised trials be analysed? BMJ. 2000;320:1197–200. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7243.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leuven E, Sianesi B. PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covarite imbalance testing. Statistical Software Components. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gershengorn HB, Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR, Scales DC, Kahn JM, Wunsch H. Variation in use of intensive care for adults with diabetic ketoacidosis. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2009–2015. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31824e9eae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen LM, Render M, Sales A, Kennedy EH, Wiitala W, Hofer TP. Intensive care unit admitting patterns in the veterans affairs health care system. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012:1–7. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Complications, failure to rescue, and mortality with major inpatient surgery in medicare patients. Ann Surg. 2009;250:1029–1034. doi: 10.1097/sla.0b013e3181bef697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amaravadi RK, Dimick JB, Pronovost PJ, Lipsett PA. ICU nurse-to-patient ratio is associated with complications and resource use after esophagectomy. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:1857–1862. doi: 10.1007/s001340000720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Cheung RB, Sloane DM, Silber JH. Educational levels of hospital nurses and surgical patient mortality. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:1617–1623. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wunsch H, Angus DC, Harrison DA, Collange O, Fowler R, Hoste EA, de Keizer NF, Kersten A, Linde-Zwirble WT, Sandiumenge A, Rowan KM. Variation in critical care services across North America and Western Europe. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2787–2789. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186aec8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Back MR, Harward TR, Huber TS, Carlton LM, Flynn TC, Seeger JM. Improving the cost-effectiveness of carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg. 1997;26:456–62. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(97)70038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraiss LW, Kilberg L, Critch S, Johansen KJ. Short-stay carotid endarterectomy is safe and cost-effective. Am J Surg. 1995;169:512–515. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valley TS, Sjoding MW, Ryan AM, Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR. Association of Intensive Care Unit Admission With Mortality Among Older Patients With Pneumonia. JAMA. 2015;314:1272–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.11068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kazaure HS, Roman SA, Rosenthal RA, Sosa JA. Cardiac Arrest Among Surgical Patients: An Analysis of Incidence, Patient Characteristics, and Outcomes in ACS-NSQIP. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:14–21. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huynh TN, Kleerup EC, Raj PP, Wenger NS. The opportunity cost of futile treatment in the ICU*. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:1977–82. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.