Abstract

In this review, methods for evaluating the properties of tissue engineered (TE) cartilage are described. Many of these have been developed for evaluating properties of native and osteoarthritic articular cartilage. However, with the increasing interest in engineering cartilage, specialized methods are needed for nondestructive evaluation of tissue while it is developing and after it is implanted. Such methods are needed, in part, due to the large inter- and intra-donor variability in the performance of the cellular component of the tissue, which remains a barrier to delivering reliable TE cartilage for implantation. Using conventional destructive tests, such variability makes it near-impossible to predict the timing and outcome of the tissue engineering process at the level of a specific piece of engineered tissue and also makes it difficult to assess the impact of changing tissue engineering regimens. While it is clear that the true test of engineered cartilage is its performance after it is implanted, correlation of pre and post implantation properties determined non-destructively in vitro and/or in vivo with performance should lead to predictive methods to improve quality-control and to minimize the chances of implanting inferior tissue.

Introduction

Joint disease and cartilage defects are a major public health issue in countries with high life expectancies. Schulz et al. estimate that over 60 million people in the US will suffer from arthritis by 2020.145 Projections are for 572,000 primary total hip and 3.5 million total knee prosthetic joint replacements annually by 2030.3, 74 Tissue engineering is viewed as a promising approach for an alternate, biological repair or replacement of defective joint tissues. Based on the size of the potential patient population, cartilage tissue engineering has the potential of becoming one of the earliest and largest drivers of tissue engineering technology.

Tissue engineered (TE) cartilage can be viewed, in aggregate, as a laboratory-grown biomaterial to repair articular lesions. As such, it must be capable of withstanding all of the simultaneous environmental constraints experienced by native tissue. The consequence of applying joint-level conditions to tissue that is inadequate in any mode is failure.5, 42, 97, 101, 103, 104, 108, 138, 146, 153, 156, 167 A key obstacle to delivering reliable TE cartilage for implantation is the large (and still poorly understood) inter- and intra-donor variability in the performance of the cellular component of the tissue. This variability affects tissue engineering critical parameters, including the magnitude and timing of responses to growth factor treatment, the composition, physical properties and the timing of accrual of the extracellular matrix (ECM), and tissue metabolic rates, and thus sensitivity to mass-transport limitations. Put simply, from donor to donor, not all TE cartilage develops at the same rate, to the same endpoint, or with the same response to external cues. Within a given donor, variables such as degree of expansion of the cells also impact the outcome. Absent non-destructive evaluation, such variability makes it makes it near-impossible to predict the timing and outcome of the engineering process at the level of any one specific piece of engineered tissue. We believe that, in practice, TE requires understanding and predicting process failures. Importantly, if issues are caught early during the development stage, one could intervene to address them or decide to abandon a preparation to avoid implant failure and unnecessary costs.

Perhaps more importantly at this point in the evolution of cartilage tissue engineering, donor-based variability also makes it difficult and tedious to attribute the impact of changing TE regimens experimentally.

Commonly used evaluation approaches tend to be end-point tests that provide hindsight, but cannot easily be adapted to forecast tissue development towards a desired product. Ultimately, they are inconclusive since the tested sample becomes unsuitable for implantation. This leads to the inability to capture failures before clinical testing, as not all tissues mature at the same rate.91 Therefore, non-destructive technologies with predictive skill are needed for evaluating TE cartilage during development, and prior to and after implantation. The evaluation should be multimodal and multiscale, in real time, and (although this is not yet always possible) should not compromise the prospects for implantation.22, 96, 166 Comprehensively assessing TE cartilage, and indeed any engineered tissue, is an interdisciplinary undertaking, which requires expertise in subject areas such as molecular and cell biology, biomedical, chemical, mechanical, and electrical engineering, advanced imaging and computer modeling.22, 96

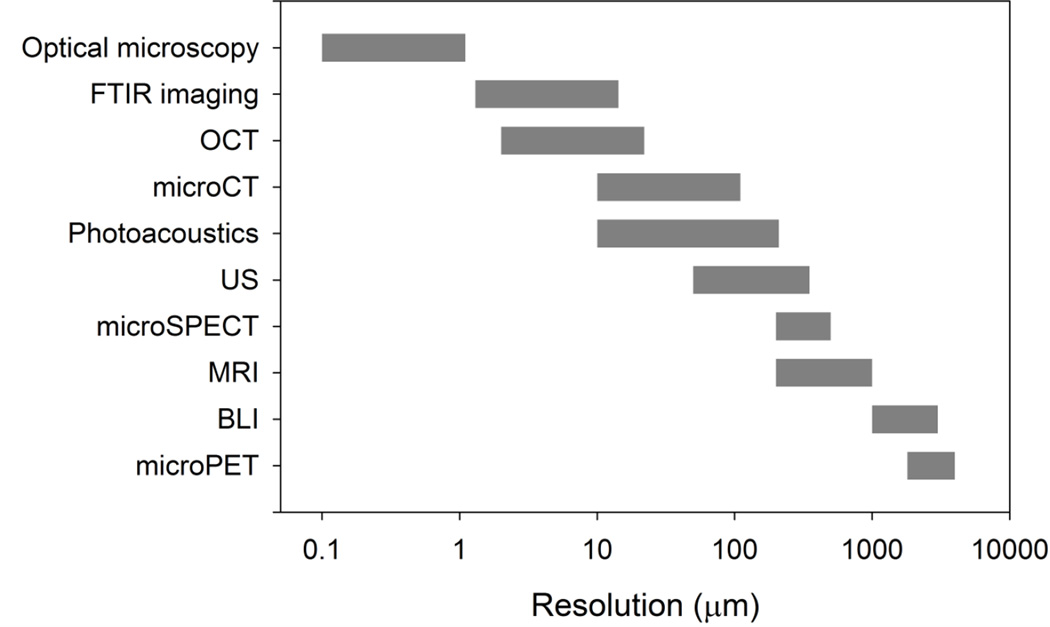

Methods for evaluating engineered cartilage are described below. They span multiple size scales, from the whole tissue to the molecular level (Figure 1). Some have been applied to normal, osteoarthritic, enzyme treated, regenerated tissue and, to a lesser extent, to developing engineered cartilage in vitro. Although evaluation of developing TE cartilage has been limited, many of these methods are nondestructive and, therefore, they could, in principle, be extended to the evaluation of tissues in vitro. The cited literature is representative of the investigations on each area, but given the depth in each of these areas, it is not possible to cite all possible references. Some applications, output parameters, technologies, and tissue types studied are summarized in tables attached to the individual sections.

Figure 1.

Approximate resolution ranges of the methods described in this review (in µm, log scale). These methods span over 4 orders of magnitude

Mechanical Tests (Table 1)

Table 1.

Applications of traditional mechanical testing to the evaluation of native, engineered or regenerated cartilage

| Output Parameter(s) | Technology | Tissue | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

18 |

|

|

|

40 |

|

|

|

180 |

Mechanical tests commonly used to evaluate cartilage include unconfined and confined compression, indentation, tensile, impact and tribological tests. Since these are well-established and have been described in numerous publications, they will not be reviewed here.40, 42, 94, 107, 138, 180 As these techniques and the resulting material properties have been used for more than thirty years, typical values are well-known and they are a “gold standard” against which engineered tissues may be compared. Historically, mechanical tests have been used to determine material properties in the lab, where issues such as contamination and potential mechanical damage as may be imposed in tensile or impact tests are not relevant. Because mechanical tests generally require physical contact with the specimen, it may be difficult, although not impossible, to perform them in a manner that preserves the tissue in a sterile state, which is essential if they are to be implanted. Thus, they may not be particularly suited to evaluating developing cartilage in vitro or in vivo.

In vivo, mechanical testing of cartilage using arthroscopic indenter probes is feasible and has been evaluated by several groups.18, 83, 90 This approach can be extended to cartilage implants and has the advantage of being able to compare the implant to adjacent host tissue. Limitations include calibration issues and the need to know the thickness of the material to determine stiffness meaningfully.164

Ultrasound (Table 2)

Table 2.

Applications of ultrasound technology to the evaluation of engineered or regenerated cartilage

| Output Parameter(s) | Technology | Tissue | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

47 |

|

|

|

76 |

|

|

|

77 |

|

|

|

57–59 |

|

|

|

35 |

|

|

|

102 |

Ultrasound (US) is an established method for non-destructive evaluation of materials and seems well-suited for in vitro evaluation of engineered cartilage. Acoustic properties such as reflection coefficient or attenuation have been used to characterize materials. Using ultrasound elastography strain fields through the thickness of a material can be determined, and inverse modeling can then be used to determine local material properties such as compressive modulus and Poisson’s ratio.30, 39, 43, 87, 124, 174, 193 This can be particularly valuable for characterizing tissue-engineered (TE) cartilage since, as noted above, it often develops non-uniformly through its thickness.

Acoustic properties, speed of sound (SOS), reflection coefficient (R), frequency dependent reflection coefficient, integrated reflection coefficient (IRC), ultrasonic roughness index (URI), attenuation and apparent integrated backscatter (AIB) have been used for characterizing normal, osteoarthritic, enzyme depleted and mechanically damaged articular cartilage, and to a lesser extent TE and spontaneously repaired cartilage.17, 47, 76, 77, 120, 129, 144, 175.

The reflection coefficient (R) is the ratio of the peak-peak amplitude of the reflected signal from the tissue-fluid interface and a fluid-air interface, that is, a reference amplitude. The frequency dependent reflection coefficient (Rc(f)) is the ratio of the frequency spectra of the signals used to compute R. The square of Rc (f) expressed, in decibels, is the energy reflection coefficient (RdBc(f)), and the frequency-averaged integral of RdBc(f) is known as the integrated reflection coefficient (IRC). Ultrasound has also been used to compute a cartilage surface roughness index (URI): the square root of the sum of the squares of the difference in the distance from the transducer to the cartilage surface relative to the mean distance. Attenuation is characterized using three measures. Amplitude attenuation is defined by and integrated attenuation as . The slope of the attenuation as a function of frequency is the broadband attenuation (BUA), which is sometimes normalized by the tissue thickness (nBUA): . In these expressions, f is the frequency and A1 and A2 are peak-to-peak amplitudes of consecutive reflections and A1(f) and A2(f) are the corresponding spectra of the reflected signals. Another often-used acoustic parameter is the apparent integrated backscatter (AIB), computed as the integral, over frequency, of the apparent energy backscattered from the material. It is considered as a measure of features of sub-resolution scatters such as size, and acoustic impedance mismatch.6, 32, 47, 84, 117, 129, 140, 165, 170, 175

Since changes in acoustic properties are indicative of changes in composition and morphology of cartilage, they have been used for evaluating engineered cartilage. For example, in surgically-created defects (4 mm diameter, 3 mm deep) filled with engineered cartilage R and AIB significantly decreased, while IRC and URI significantly increased when compared with intact cartilage close to the repair site.170 In contrast, in the same study, surgical defects that were left to heal without an implant, only AIB had a significant decrease. A similar investigation using ultrasound to evaluate spontaneous repair of surgically created 6 mm diameter lesions that did not penetrate the calcified zone found that R was significantly lower in the lesion and URI was significantly higher when compared with intact tissue.76

A different approach to quantifying the acoustic properties of cartilage, pioneered by Hattori and co-workers, uses wavelet maps to quantify reflected A-mode signals in terms of maximum magnitude and echo duration.56–59 In regenerated cartilage, wavelet analysis differentiated between preselected groups of surgically created lesions filled with hyaline-like engineered cartilage or fibrocartilage. However, only a weak correlation was found between histological grade and the maximum magnitude in this investigation.58 In a related investigation of three different surgical models, maximum magnitude was significantly higher in spontaneous repair of a deep defect as opposed to superficial defects.57

The investigations cited above have shown that acoustic properties can differentiate between native and engineered cartilage. However, acoustic properties alone are not indicators of the composition or mechanical properties of cartilage. There are, however, correlations between acoustic properties, and composition and mechanical properties. We used hydrogels as surrogates for cartilage to develop correlations between mechanical properties of cartilage and SOS, density and solid and fluid volume fractions.95, 173 Most such correlations have been identified in native, enzyme treated and osteoarthritic cartilage,69, 117, 129, 165, 175 but it is not unreasonable to suggest that such correlations will also exist for engineered cartilage. With respect to composition, proteoglycan, collagen and water content are significantly correlated with R, and SOS, IRC and URI.119, 129, 165.

Based on the idea that SOS is related to modulus and density, we have developed an approach to using ultrasound for evaluating the mechanical properties of TE cartilage while it is contained in the sterile environment of a bioreactor.95, 173 Agarose hydrogels were used as surrogates for engineered cartilage since they can easily be made with consistent properties, and are considerably less expensive than engineered cartilage. We first showed that the aggregate modulus could be predicted from measured SOS and known gel concentration using a poroelastic model for wave propagation, i.e., the gel is modeled as having solid and fluid phases.173 However, for a TE construct, the composition would not be known. Thus, we developed a statistical model that yielded an excellent prediction of modulus based solely on measured SOS.95

The approaches described above give average mechanical properties of the material. However, it is well known that the properties of TE and native cartilage are depth-dependent. Optical methods have been developed for evaluating the depth-dependent properties of native cartilage, but as these use sections through the tissue, they are destructive.19, 20, 142, 143 Elastography, however, provides a promising approach for evaluating depth dependent properties of tissue in a bioreactor.35, 50, 102, 192 The potential value of US elastography was recognized by McCredie et al., who noted that the elastic properties of engineered cartilage were “reasonably depth-dependent.”102 We recently demonstrated the feasibility of using ultrasound elastography to evaluate depth-dependent deformation of engineered constructs in a sealed bioreactor.35 We found that strains in interior regions were greater than those near the surface, which is consistent with the morphology of engineered cartilage: due to limits on diffusion, the interior of a construct often fails to develop cartilage-like tissue. Ultrasound elastography is dependent on the presence of acoustic inhomogeneities in the material that shift as the material is deformed. Therefore, a potential limitation of US elastography is that a tissue could be structurally, but not acoustically inhomogeneous.

Photoacoustics (Table 3)

Table 3.

Applications of photoacoustic technology to the evaluation of engineered or regenerated cartilage

| Output Parameter(s) | Technology | Tissue | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

62 141 |

|

|

|

63 |

Photoacoustic methods have several characteristics that make them attractive for evaluation of engineered cartilage. They are noninvasive and have been used to evaluate tissues in vivo and ex vivo, and, like ultrasound-based methods, are generally believed to be safe.53, 141, 160, 161, 186, 187

Ishihara et al., were the first (to the best of their knowledge) to show that viscoelastic properties of material could be estimated using photoacoustic methods.62 This approach is based on the idea that the ratio of the viscous to elastic properties is related to the decay time of the stress wave. They used gelatin and tissue engineered cartilage to demonstrate the feasibility of determining viscoelastic material properties using photoacoustics. To establish feasibility, viscoelastic properties obtained from photoacoustic wave propagation were compared with those obtained from a “conventional measurement” of using a rheometer. Although light in the ultraviolet range was used, the investigators cautioned that this may not ideal for use with biological tissues.

This work was extended to include an in-depth evaluation of the viscoelastic and biochemical properties of tissue-engineered cartilage cultured from rabbit chondrocytes.63 A strong inverse correlation (0.98) between viscoelastic properties (tan δ) and relaxation times over a twelve week culture period was found. This suggests that the tissue was becoming more elastic and less viscous over the culture period. Relaxation time was also correlated strongly with biochemical composition: total chondroitin sulfate, the ratio of chondroitin 4 sulfate to chondroitin 6 sulfate, and total collagen. The ability of photoacoustic methods to identify a mechanical property and biochemical composition makes this a potential valuable non-invasive approach for evaluating the development of engineered cartilage prior to implantation.

The feasibility of evaluating engineered implants, in vivo, is suggested by photoacoustic tomography (PAT) imaging that has been used to evaluate normal and osteoarthritic cartilage.161, 185, 186 These investigations showed that PAT can identify joint structures as well as compositional differences between normal and osteoarthritic cartilage.

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT, Table 4)

Table 4.

Applications OCT technology to the evaluation of engineered or regenerated cartilage

OCT has been used to evaluate normal and osteoarthritic cartilage and, to a lesser extent, regenerated or TE cartilage. However, the inherent characteristics of this approach suggest it has the potential to be a valuable technology for in vitro evaluation of engineered cartilage.99 Like ultrasound, OCT is thought to be nondestructive. Although its depth of penetration, 1 – 2 mm, is small when compared to ultrasound or MRI, it is sufficient for evaluating the full thickness of cartilage on many joints and, for thicker cartilage constructs in a bioreactor, images can be formed from both sides of the sample, thus doubling the thickness that can be evaluated. Also, when compared with ultrasound, the axial resolution of OCT is better by one to two orders of magnitude. This places OCT between ultrasound (with lower resolution), and confocal and two-photon microscopy that have higher resolution.99 OCT has been used to evaluate cartilage in situ through an arthroscope, and tissue explants.46, 99, 100, 113, 134, 162 In addition, OCT is sensitive to collagen orientation and fibrillation, which makes it well suited for evaluating osteoarthritic and repaired tissue.29, 34, 60, 92, 162 Using OCT areas of fibro-cartilage that are indicative of attempted but inadequate repair have been identified, although these might not be observed on visual arthroscopic examination of a joint.34, 60 Using OCT, differences in the ultrastructural features of regenerated cartilage, and the integration of host and regenerated tissue have been evaluated.46

The speckle pattern in OCT images suggests that this approach could be coupled with elastography to determine internal deformation and mechanical properties of tissues. However, a PubMed search (June 2015) using the terms “elastography” “optical coherence” and “cartilage” produced only one review article suggesting that this could be used to evaluate cartilage.100 In contrast, a search using the terms “elastography” and “optical coherence” resulted in 130 citations and searching “optical coherence” and “cartilage” produced 96 citations.

Reporter-based Imaging (Table 5)

Table 5.

Applications reporter gene imaging for evaluation of native, engineered or regenerated cartilage

| Output Parameter(S) | Technology | Tissue | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

88 |

|

|

|

132 |

|

|

|

33 |

|

|

|

82 |

|

|

|

106 |

|

|

|

184 |

|

|

|

135 |

Reporter gene–based imaging was developed to track molecular and cellular events.45 Originally, reporter genes (e.g., luciferase) were driven by constitutively active promoters in the cells to be transplanted or implanted.88 The imaging signal from luciferin acts as a beacon, and is strong enough to be detected in large scale tissue constructs and even after implantation in small animals.88 For medium or larger sized animals, a positron emission tomography (PET) imaging reporter can be used in place of luciferase for clinically relevant and quantitative live animal imaging.132 For example, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) implanted in a porcine model of degenerative intervertebral discs (IVD) to regenerate fibro-cartilage132 have been reporter-gene transduced and then tracked by PET imaging. However, this type of imaging only demonstrates the targeted deposition and retention of the implanted cells. No information about the actions of these cells during repair or regeneration can be obtained.

For this, event-specific or tissue-specific reporters, rather than constitutive reporters are needed. For example, type II collagen (Col2) expression is an early event during articular cartilage development.51 Col2-GFP transgenic mice have been developed,33 and a reporter gene with Col2 promoter-driven luciferase was developed82 to track chondrogenic differentiation with more experimental flexibility. Similarly, the transcription factor Sox 9 is a master regulator of MSC chondrogenic differentiation, and plasmids containing full-length or truncated Sox9 promoters have been developed. These have been used for studying campomelic dysplasia and autosomal sex-reversal; they can track Sox expression patterns during TE chondrogenesis.98, 189,51, 66, 179

An important aspect of cartilage TE is the balance between catabolic and anabolic signals in real time during the late-stage of cartilage formation or in newly formed tissue. Proteases and proteinases, such as the matrix metallopeptidases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs), play an important role in TE cartilage remodeling both pre- and post-implantation, and in many cartilage-related diseases. Among the MMPs, the principal neutral proteinases MMP-1, -3, -8 and -13 are of particular interest because they are capable of degrading native fibrillar collagens in the ECM.70 MMP-13 promoter-driven reporters for imaging MMP-13 are available.106, 184, 191 Advantages of the MMP-13 reporter system are that destructive sampling can be avoided, and repeated imaging can be used to follow MMP-13 expression, which fluctuates during cartilage re-modeling. Similarly, reporters driven by the TIMP3 promoter are available.135, 182

In the context of bioluminescent imaging (BLI) reporter systems, it is usually a lengthy process to identify and optimize a cartilage-specific promoter sequence because tissue-specificity usually depends on four to five enhancers interacting with (co-)activator(s) and co-repressors.168 Non-coding RNAs hold great potential in diagnosis and treatment. Unlike promoter sequences, it is a potentially much simpler approach to use a miRNA-responsive reporter construct to track pathway regulation of chondrogenic differentiation, as this by-passes the need to validate which promoter/enhancer sequences or binding motifs to keep or cut. Furthermore, an imaging marker reflecting the miRNA expression can provide spatial localization as well as quantification. miRNAs from either synovial fluid or circulation have also been investigated in the process of chondrogenesis, and for disease diagnosis.110

In vivo reporter imaging devices, typified by the PERKIN-Elmer In Vivo Imaging Systems (IVIS) are capable of imaging fluorescent and bioluminescent reporters and fluorescent probes including fluorophores, fluorescent proteins, dyes and conjugates. The systems use short cut-off filters and spectral unmixing algorithms to allow separation of multiple concurrent reporters. These imaging systems have the capability of tracking gene expression long-term after implantation; thus IVIS has been used to track implanted transfected mesenchymal stem cells for over 3 months.89 Similarly, the infection of cells in-situ, using an intra-articularly injected AAV reporter has been demonstrated and could be monitored for up to a year.128 Bioluminescent imaging (BLI) data can be co-registered with CT or MRI images to provide anatomical context, this is an integrated feature in newer IVIS systems.11 IVIS has additional potential applications useful for evaluating the status of implanted TE materials, For example, Xie et al. have used hydrocyanine probes 73 to measure reactive oxygen species produced in an OA model.188 Further, Na et al. have demonstrated that IVIS can be used to monitor the sustained release of probe-conjugated drugs from implanted constructs over time (weeks).111 In vivo, BLI provides fairly low anatomic resolution. For high (single cell) spatial resolution the BLI reporters can be replaced by fluorescent reporters to track cells within newly formed cartilage by two-photon imaging, or for histological identification by fluorescence microscopy.37

Two-Photon Imaging (Table 6)

Table 6.

Applications of two-photon microscopy to the evaluation of native, engineered or regenerated cartilage

| Output Parameter(S) | Technology | Tissue | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

24 |

Two-photon imaging can identify labeled cells by imaging different fluorescent proteins (e.g., green fluorescent protein. GFP or red fluorescent protein, RFP) at the single cell level, thus overcoming the limited spatial resolution of BLI and PET/SPECT imaging. This bridges the gap between imaging and histological evaluation. As above (reporter-gene imaging), the cells can be labeled with beacon constructs or with event-specific constructs that allow tracking of differentiation steps, such as expression of specific genes.

Textural analysis of the ECM can also be utilized, as it has been applied to confocal images.61 Homogenous texture is characterized by high angular second moment, one of the 9 parameters for textural analysis based on Haralik’s method.54 In addition, principal components analysis can help to reduce the complexity of data-analysis for imaging collagen molecules, and to better quantitatively characterize type II collagen fibers or bundles of types I/II collagens relevant to cartilage quality evaluation.25

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI, Table 7)

Table 7.

Applications MRI technology to the evaluation of engineered or regenerated cartilage

MRI elastography (MRE) is also used to determine depth dependent properties of native and engineered cartilage.52, 55, 72, 86, 114–116, 190 Specialized pulse sequences are used to encode tissue deformation that are synchronized with externally applied loads or displacements.55, 114, 116, 190 Using MRE to evaluate developing TE construct requires specialized bioreactors, and the initial equipment cost is considerably greater than that for ultrasound systems. Operating costs (technician time, machine time, computer post-processing) for MRI are also greater than those for US, which is a potential disadvantage especially if a large numbers of samples are being evaluated. However, unlike ultrasound elastography, MRE can be used on tissues that are homogeneous, which could be an advantage as constructs mature.

MRI has been used to evaluate the biochemical composition (proteoglycans and collagen), cell density and water content in normal, osteoarthritic and regenerated cartilage.48, 55, 72, 80, 85, 86, 114–116 GAGs are an essential part of the load carrying mechanism in articular cartilage and they are known to decrease in osteoarthritic cartilage. A potentially attractive feature of MRI for evaluation of TE cartilage is the ability to determine glycosaminoglycan (GAG) concentration using delayed Gadolinium Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Cartilage (dGEMRIC).9 dGEMRIC allows measurement of GAGs concentration since regions of high GAGs exclude gadolinium contrast agents during MR imaging.8

In engineered and repaired cartilage GAGs are typically lower than in native tissue, although they can increase to normal levels over long times.48, 181

MicroCT (Table 8)

Table 8.

Applications of microCT to the evaluation of native, engineered or regenerated cartilage

| Output Parameter(S) | Technology | Tissue | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

36 |

|

|

|

118 |

|

|

|

125 |

|

|

|

148 |

Cartilage signal by micro-CT is weak as cartilage does not attenuate X-rays very well. However, contrast enhanced micro-CT using a gadolinium probe has shown promising results on cartilage explants and could be applicable to TE cartilage.36 Recently, the feasibility determining collagen orientation using micro-CT in conjunction with the labeling agents phosphotungstic acid and phosphomolybdic acid was demonstrated.118 The effectiveness of the labeling varied between human and equine cartilage.

The CT-based measurement of chondrocyte differentiation is possible using the clinically available CT contrast agent Hexabrix-320 (Mallinckrodt, Hazelwood, MO). Hexabrix contains ioxaglate, a negatively charged hexaiodinated dimer. After being preferentially absorbed by cartilage, it yields an equilibrium distribution, which can be measured by CT due to the radio-opacity of the contrast iodine that is inversely related to the density of the negatively charged sulfated GAG, similar to the mechanism of ionic GdTPA-2 used in dGEMRIC. Hexabrix has shown promising results with ex vivo or in situ imaging of animal joints using microCT to assess 3D cartilage composition and morphology,125 and has been examined for use in detecting diseases associated with degeneration of articular cartilage.148 The properties of the contrast agent and the mechanism of target binding for detection make this reagent suitable for use on extracted samples or tissue explants; in vivo imaging on live animal models remains challenging with this modality.

Nuclear Imaging (Table 9)

Table 9.

Applications radionuclide imaging for evaluation of native, engineered or regenerated cartilage

| Output Parameter(S) | Technology | Tissue | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

123 |

|

|

|

151, 152 |

|

|

|

157 |

Challenges in applying nuclear and other imaging techniques to tissue engineering were summarized recently by Appel et al.4 The focus here is on imaging a specific target of interest. The radio-tracer, N-[triethylammonium]-3-propyl-[15]ane-N5 radiolabeled with99mTc (99mTc-NTP 15-5), exhibits very high affinity for cartilage due to ionic interaction between its quaternary ammonium group and polyanionic glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) present in cartilage.123 This tracer can be used for single photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) imaging of GAG concentration and can be either a companion or alternative to dGEMRIC.

Uptake of another radiolabeled tracer,99mTC-labeled glucosamine sulfate (GS), can be used as a direct and quantitative biomarker for stem cell derived chondrocyte function in cartilage regeneration via SPECT imaging.152 GS and chondroitin sulfate (CS) serve as substrates for biosynthesis of GAGs. Because of transport issues with higher molecular weight hyaluronan, the lower molecular weight GS and CS are more effective tracers.7 Chondrocytes use GS for CS synthesis. Non-labeled native GS has therapeutic applications in osteoarthritis (OA) and radiolabeled GS was initially developed for scintigraphic detection of OA.150, 152 The uptake of radiolabeled GS is different from99mTc-NTP 15-5, which binds to its target based on ionic interaction, charge does not play a major role for GS uptake, but facilitates charge-mediated diffusion of GS. Further investigation is required on the sensitivity and specificity of GS for use in assessing stem cell-based cartilage repair.

[99mTc]-RP805 is a highly sensitive MMP-targeted radiotracer that has been used in a murine model of post-myocardial infarction remodeling. It is designed for targeting MMP-2,157 but actually has a greater affinity for MMP-13.157 SPECT imaging of MMP-13 with this tracer has potential for imaging TE cartilage, and animal models of OA.

Spectroscopic Methods (Table 10)

Table 10.

Applications FTIR and NIRS technology to the evaluation of engineered or regenerated cartilage

| Output Parameter(s) | Technology | Tissue | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

14 |

|

|

|

68 131 |

|

|

|

12 |

|

|

|

10 |

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) and near infrared (NIR) spectroscopy have been used to evaluate tissue composition and collagen orientation in native, osteoarthritic, engineered and regenerated cartilage.1, 2, 10, 12–15, 23, 38, 68, 126, 131, 137, 154, 155, 178 The specificity and sensitivity of spectroscopic methods make them a potentially attractive approach for evaluating cartilage development. Using FTIR, for example, images of the distribution of tissue components can be made with a resolution of 6.25 µm.14 An in-depth review of FT-IR for evaluating native and engineered cartilage has been published by Boskey and Camacho.15 Here, we will focus here on applications of spectroscopic methods for the evaluation of engineered and regenerated cartilage.

The use of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy imaging (FT-IRIS) to evaluate compositional and structural characteristics of regenerated cartilage was demonstrated by Bi et al.14 They showed that six months after microfracture in an equine model (knee) that PG is less than in surrounding native tissue and that, in general, collagen alignment does not follow the arcade-like structure of native cartilage. However, on the surface collagen appeared to be parallel to the joint surface, and had integrated with surrounding tissue.

FT-IRIS has also been used to evaluate PG and collagen content and distribution in TE cartilage.68 In this case, cartilage was grown using chick chondrocytes in a hollow fiber bioreactor. Results showed that PG was greater near the inflow than outflow regions, while collagen was similar between inflow and outflow.

Near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) is particularly attractive since it can penetrate the full thickness of engineered cartilage constructs, it is nondestructive and tissue composition can be determined in seconds rather than several hours as needed for biochemical analyses.10 Baykal et al, investigated the use of NIRS for evaluating matrix composition in developing engineered cartilage constructs.10 Using a broad spectral range (800 – 6000 cm−1, 4 cm−1 resolution) showed that NIRS could be used to predict matrix development in engineered cartilage constructs.

Medium Analysis (Table 11)

Table 11.

Applications of Medium analysis to the evaluation of engineered cartilage in culture

| Output Parameter(s) | Technology | Tissue | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

122, 127 |

|

|

|

26, 28, 65, 136, 159 |

|

|

|

78, 79 |

We and others have reviewed the effects of medium formulations and optimization on in vitro chondrogenesis by stem cells.16, 21, 31, 41, 64, 93, 109, 127, 133, 177, 183 During TE, the culture medium provides key nutrients (oxygen, glucose), building blocks for ECM synthesis (amino acids), and signaling molecules which direct differentiation and ECM synthesis (TGF-β, FGFs, BMPs). Much information on the state of the cells can be derived from ongoing analysis of the culture medium during TE. Thus, deviations in the levels of nutrients and metabolites (e.g., lactate) can be predictive of the condition of the samples. Similarly, physiological rates (e.g., respiration rate) are critical for determining organism function.44 Consumption or production rates for any molecule can be evaluated from mass balance by monitoring the medium outside of the tissue construct; monitoring the uptake/production of key biomolecules can provide dynamic, nondestructive, and minimally-invasive assessments of the status of the engineered tissue.49, 121, 127, 176

Ultimately, the ECM produced by the cells determines the quality of the engineered implant. Cartilage development is characterized by gradual changes in the ECM’s GAG composition and resulting PG architecture and the presence of specific collagen types.71, 130 Relative distributions of different GAGs in the ECM determines the type of cartilage, and can be predictive of its maturity and anabolic/catabolic and mechanical performance and durability.27, 28, 65, 67, 71, 75, 81, 105, 112, 139, 147, 149, 163, 171, 172 Generally, this is a destructive assessment of the ECM, however, methods have been proposed to non-destructively assess the ECM composition of engineered cartilage, including MRI and fluorescence spectroscopy coupled to ultrasound-backscattered microscopy.136, 159 These approaches estimate total GAG.26 Interestingly, in culture, not all of the ECM components secreted by the cells are incorporated into the developing cartilage ECM.79 Rather, a significant fraction of these structural molecules (and their processing enzymes) partition into the culture medium and can be quantified therein.78 Thus, the maturity of the ECM and the chondrocyte’s synthetic program can be assessed non-destructively over time by sampling and analyzing the culture medium.

Hybrid Methods

The methods described above have been combined or used with other technologies to enhance the evaluation of cartilage. For example, Sun et al. used time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy (TRFS) and ultrasound backscatter microscopy (UBM) to simultaneously evaluate acoustic, mechanical and biochemical properties of normal and enzymatically degraded cartilage.158 They found that TRFS was strongly correlated with collagen content and Young’s modulus, while UBM was used to evaluate morphological properties. As these methods are nondestructive, they are potentially useful for evaluating engineered cartilage during development and prior to implantation. As mentioned above, BLI imagery can be co-registered with CT or MRI images for additional anatomical context.11

Ultrasound has also been combined with OCT to enhance the evaluation of osteochondral and chondral defects.169 US and OCT roughness indices, integrated reflection coefficients and apparent integrated backscatter (AIB and OBS) were computed. While there were significant correlations between these two approaches, the better resolution of OCT provided “more reliable measurements of the cartilage surface integrity” while the greater depth of penetration of US provided more information about the inner structures of the regenerated tissue.

Summary

As described in this review, methods for evaluating a broad range of properties of native and osteoarthritic articular cartilage have been developed. To a lesser extent, these methods have been used to evaluate regenerated cartilage, and to an even less extent, developing tissue. However, with the increasing interest in engineering cartilage, methods are needed for nondestructive evaluation of tissue while it is developing and after it is implanted. A subset of the methods described here are applicable to nondestructive evaluation of developing tissues in vitro, and some can be used to monitor the state of the tissue post-implantation. Ultimately, the true test of engineered cartilage is its performance after it is implanted. In the future, correlation of pre and post implantation properties and performance will lead to predictive methods that should improve quality control and minimize the risk of implanting inferior tissue.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering under award number R01 EB20367-01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial relationships that may cause a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Afara I, Prasadam I, Crawford R, Xiao Y, Oloyede A. Non-destructive evaluation of articular cartilage defects using near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy in osteoarthritic rat models and its direct relation to Mankin score. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20:1367–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afara IO, Prasadam I, Moody H, Crawford R, Xiao Y, Oloyede A. Near infrared spectroscopy for rapid determination of Mankin score components: a potential tool for quantitative characterization of articular cartilage at surgery. Arthroscopy. 2014;30:1146–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.04.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson G, Bouchard J, Bozic K, Campbell R, Cisternas M, Correa A, Cosman F, Cragan J, D’Andrea K, Doernberg N, Dormans J, Elderkin A, Fershteyn Z, Foreman A, Gitelis S, Gnatz S, Haralson R, Helmick C, Hochberg M, Hu S, Katz J, King T, Kirk R, Kurtz S, Lane N, Looker A, McGowan J, Miller A, Novich R, Olney R, Panopalis P, Pasta D, Pollak A, Puzas J, Richards B, Sestito J, Siffel C, Sponseller P, St. Clair E, Stuart A, Templeton K, Thompson G, Tosi L, Tosteson A, Ward W, Watkins-Castillo S, Weinstein S, Wieting M, Wright J, Yelin E. The burden of musculoskeletal diseases in the united states. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2008. Arthritis and related conditions; pp. 75–102. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appel AA, Anastasio MA, Larson JC, Brey EM. Imaging challenges in biomaterials and tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2013;34:6615–6630. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Athanasiou KA, Rosenwasser MP, Buckwalter JA, Malinin TI, Mow VC. Interspecies comparisons of in situ intrinsic mechanical properties of distal femoral cartilage. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 1991;9:330–340. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aula AS, Toyras J, Tiitu V, Jurvelin JS. Simultaneous ultrasound measurement of articular cartilage and subchondral bone. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 18:1570–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balogh L, Polyak A, Mathe D, Kiraly R, Thuroczy J, Terez M, Janoki G, Ting Y, Bucci LR, Schauss AG. Absorption, uptake and tissue affinity of high-molecular-weight hyaluronan after oral administration in rats and dogs. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2008;56:10582–10593. doi: 10.1021/jf8017029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bashir A, Gray ML, Boutin RD, Burstein D. Glycosaminoglycan in articular cartilage: in vivo assessment with delayed Gd(DTPA)(2-)-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 1997;205:551–558. doi: 10.1148/radiology.205.2.9356644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bashir A, Gray ML, Hartke J, Burstein D. Nondestructive imaging of human cartilage glycosaminoglycan concentration by MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1999;41:857–865. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199905)41:5<857::aid-mrm1>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baykal D, Irrechukwu O, Lin PC, Fritton K, Spencer RG, Pleshko N. Nondestructive assessment of engineered cartilage constructs using near-infrared spectroscopy. Appl Spectrosc. 2010;64:1160–1166. doi: 10.1366/000370210792973604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beattie BJ, Klose AD, Le CH, Longo VA, Dobrenkov K, Vider J, Koutcher JA, Blasberg RG. Registration of planar bioluminescence to magnetic resonance and x-ray computed tomography images as a platform for the development of bioluminescence tomography reconstruction algorithms. J Biomed Opt. 2009;14:024045. doi: 10.1117/1.3120495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bi X, Li G, Doty SB, Camacho NP. A novel method for determination of collagen orientation in cartilage by Fourier transform infrared imaging spectroscopy (FT-IRIS) Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:1050–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bi X, Yang X, Bostrom MP, Bartusik D, Ramaswamy S, Fishbein KW, Spencer RG, Camacho NP. Fourier transform infrared imaging and MR microscopy studies detect compositional and structural changes in cartilage in a rabbit model of osteoarthritis. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;387:1601–1612. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0910-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bi X, Yang X, Bostrom MP, Camacho NP. Fourier transform infrared imaging spectroscopy investigations in the pathogenesis and repair of cartilage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:934–941. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boskey A, Camacho NP. FT-IR imaging of native and tissue-engineered bone and cartilage. Biomaterials. 2007;28:2465–2478. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.11.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyette LB, Creasey OA, Guzik L, Lozito T, Tuan RS. Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells display enhanced clonogenicity but impaired differentiation with hypoxic preconditioning. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014;3:241–254. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bridal SL, Fornes P, Bruneval P, Berger G. Correlation of ultrasonic attenuation (30 to 50 MHz and constituents of atherosclerotic plaque. Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. 1997;23:691–703. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(97)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brommer H, Laasanen MS, Brama PA, van Weeren PR, Helminen HJ, Jurvelin JS. In situ and ex vivo evaluation of an arthroscopic indentation instrument to estimate the health status of articular cartilage in the equine metacarpophalangeal joint. Veterinary Surgery. 2006;35:259–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2006.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buckley MR, Bergou AJ, Fouchard J, Bonassar LJ, Cohen I. High-resolution spatial mapping of shear properties in cartilage. Journal of Biomechanics. 2010;43:796–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buckley MR, Gleghorn JP, Bonassar LJ, Cohen I. Mapping the depth dependence of shear properties in articular cartilage. Journal of Biomechanics. 2008;41:2430–2437. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burke DP, Khayyeri H, Kelly DJ. Substrate stiffness and oxygen availability as regulators of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation within a mechanically loaded bone chamber. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2015;14:93–105. doi: 10.1007/s10237-014-0591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butler D, Lewis J, Frank C, Banes A, Caplan AI, de Deyne P, Dowling M-A, Fleming B, Glowacki J, Guldberg R, Johnstone B, Kaplan D, Levenston M, Lotz J, Lu E, Lumelsky N, Mao JJ, Mauck R, McDevitt C, Mejia L, Murray M, Ratcliffe A, Spindler K, Tashman S, Wagner C, Weisberg E, Williams C, Zhang R. Evaluation criteria for musculoskeletal and craniofacial tissue engineering constructs: a conference report. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:2089–2104. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Camacho NP, West P, Torzilli PA, Mendelsohn R. FTIR microscopic imaging of collagen and proteoglycan in bovine cartilage. Biopolymers. 2001;62:1–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2001)62:1<1::AID-BIP10>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campagnola PJ, Loew LM. Second-harmonic imaging microscopy for visualizing biomolecular arrays in cells, tissues and organisms. Nature Biotechnology. 2003;21:1356–1360. doi: 10.1038/nbt894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campagnola PJ, Millard AC, Terasaki M, Hoppe PE, Malone CJ, Mohler WA. Three-dimensional high-resolution second-harmonic generation imaging of endogenous structural proteins in biological tissues. Biophysical Journal. 2002;82:493–508. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75414-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carrino DA, Onnerfjord P, Sandy JD, Cs-Szabo G, Scott PG, Sorrell JM, Heinegard D, Caplan AI. Age-related changes in the proteoglycans of human skin. Specific cleavage of decorin to yield a major catabolic fragment in adult skin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:17566–17572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300124200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caterson B. Fell-Muir Lecture: chondroitin sulphate glycosaminoglycans: fun for some and confusion for others. International Journal of Experimental Pathology. 2012;93:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2011.00807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caterson B, Mahmoodian F, Sorrell JM, Hardingham TE, Bayliss MT, Carney SL, Ratcliffe A, Muir H. Modulation of native chondroitin sulphate structure in tissue development and in disease. Journal of Cell Science. 1990;97(Pt 3):411–417. doi: 10.1242/jcs.97.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cernohorsky P, Kok AC, Bruin DM, Brandt MJ, Faber DJ, Tuijthof GJ, Kerkhoffs GM, Strackee SD, van Leeuwen TG. Comparison of optical coherence tomography and histopathology in quantitative assessment of goat talus articular cartilage. Acta Orthop. 2015;86:257–263. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2014.979312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cespedes I, Ophir J, Ponnekanti H, Maklad N. Elastography: elasticity imaging using ultrasound with application to muscle and breast in vivo. Ultrasonic imaging. 1993;15:73–88. doi: 10.1177/016173469301500201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chase LG, Yang S, Zachar V, Yang Z, Lakshmipathy U, Bradford J, Boucher SE, Vemuri MC. Development and characterization of a clinically compliant xeno-free culture medium in good manufacturing practice for human multipotent mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2012;1:750–758. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2012-0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cherin E, Saied A, Pellaumail B, Loeuille D, Laugier P, Gillet P, Netter P, Berger G. Assessment of rat articular cartilage maturation using 50-MHz quantitative ultrasonography. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9:178–186. doi: 10.1053/joca.2000.0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho JY, Grant TD, Lunstrum GP, Horton WA. Col2-GFP reporter mouse--a new tool to study skeletal development. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2001;106:251–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chu CR, Lin D, Geisler JL, Chu CT, Fu FH, Pan Y. Arthroscopic microscopy of articular cartilage using optical coherence tomography. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2004;32:699–709. doi: 10.1177/0363546503261736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung CY, Heebner J, Baskaran H, Welter JF, Mansour JM. Ultrasound Elastography for Estimation of Regional Strain of Multilayered Hydrogels and Tissue-Engineered Cartilage. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2015;43:2991–3003. doi: 10.1007/s10439-015-1356-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cockman MD, Blanton CA, Chmielewski PA, Dong L, Dufresne TE, Hookfin EB, Karb MJ, Liu S, Wehmeyer KR. Quantitative imaging of proteoglycan in cartilage using a gadolinium probe and microCT. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2006;14:210–214. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Contag CH, Jenkins D, Contag PR, Negrin RS. Use of reporter genes for optical measurements of neoplastic disease in vivo. Neoplasia. 2000;2:41–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.David-Vaudey E, Burghardt A, Keshari K, Brouchet A, Ries M, Majumdar S. Fourier Transform Infrared Imaging of focal lesions in human osteoarthritic cartilage. Eur Cell Mater. 2005;10:51–60. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v010a06. discussion 60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drakonaki EE, Allen GM, Wilson DJ. Ultrasound elastography for musculoskeletal applications. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:1435–1445. doi: 10.1259/bjr/93042867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DuRaine GD, Arzi B, Lee JK, Lee CA, Responte DJ, Hu JC, Athanasiou KA. Biomechanical evaluation of suture-holding properties of native and tissue-engineered articular cartilage. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2015;14:73–81. doi: 10.1007/s10237-014-0589-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farrell MJ, Shin JI, Smith LJ, Mauck RL. Functional consequences of glucose and oxygen deprivation on engineered mesenchymal stem cell-based cartilage constructs. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2015;23:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forster H, Fisher J. The influence of continuous sliding and subsequent surface wear on the friction of articular cartilage. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. Part H. Journal of Engineering in Medicine. 1999;213:329–345. doi: 10.1243/0954411991535167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fortin M, Buschmann MD, Bertrand MJ, Foster FS, Ophir J. Dynamic measurement of internal solid displacement in articular cartilage using ultrasound backscatter. Journal of Biomechanics. 2003;36:443–447. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fritts HW, Jr, Richards DW, Cournand A. Oxygen consumption of tissues in the human lung. Science. 1961;133:1070–1072. doi: 10.1126/science.133.3458.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gambhir S, Yaghoubi S. Molecular Imaging with Reporter Genes. New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gavenis K, Schmitt R, Eder K, Mumme T, Andereya S, Schneider U, Muller-Rath R. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) to evaluate cartilage tissue engineering. Z Orthop Unfall. 2008;146:788–792. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1038948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gelse K, Olk A, Eichhorn S, Swoboda B, Schoene M, Raum K. Quantitative ultrasound biomicroscopy for the analysis of healthy and repair cartilage tissue. Eur Cell Mater. 2010;19:58–71. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v019a07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gillis A, Bashir A, McKeon B, Scheller A, Gray ML, Burstein D. Magnetic resonance imaging of relative glycosaminoglycan distribution in patients with autologous chondrocyte transplants. Investigative Radiology. 2001;36:743–748. doi: 10.1097/00004424-200112000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gillooly JF, Brown JH, West GB, Savage VM, Charnov EL. Effects of size and temperature on metabolic rate. Science. 2001;293:2248–2251. doi: 10.1126/science.1061967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ginat DT, Hung G, Gardner TR, Konofagou EE. High-resolution ultrasound elastography of articular cartilage in vitro. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2006;(Suppl):6644–6647. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2006.260910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldring MB, Tsuchimochi K, Ijiri K. The control of chondrogenesis. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2006;97:33–44. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Griebel AJ, Khoshgoftar M, Novak T, van Donkelaar CC, Neu CP. Direct noninvasive measurement and numerical modeling of depth-dependent strains in layered agarose constructs. Journal of Biomechanics. 2014;47:2149–2156. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hagiwara Y, Izumi T, Yabe Y, Sato M, Sonofuchi K, Kanazawa K, Koide M, Saijo Y, Itoi E. Simultaneous evaluation of articular cartilage and subchondral bone from immobilized knee in rats by photoacoustic imaging system. J Orthop Sci. 2015;20:397–402. doi: 10.1007/s00776-014-0692-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haralik RM, Shanmugan K, Dinstein IS. Textural features for imagine classification. IEEE Trans Systems Management Cybernetics. 1973;3:610–621. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hardy PA, Ridler AC, Chiarot CB, Plewes DB, Henkelman RM. Imaging articular cartilage under compression--cartilage elastography. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2005;53:1065–1073. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hattori K, Mori K, Habata T, Takakura Y, Ikeuchi K. Measurement of the mechanical condition of articular cartilage with an ultrasonic probe: quantitative evaluation using wavelet transformation. Clinical Biomechanics. 2003;18:553–557. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(03)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hattori K, Takakura Y, Morita Y, Takenaka M, Uematsu K, Ikeuchi K. Can ultrasound predict histological findings in regenerated cartilage? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:302–305. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hattori K, Takakura Y, Ohgushi H, Habata T, Uematsu K, Ikeuchi K. Novel ultrasonic evaluation of tissue-engineered cartilage for large osteochondral defects--non-invasive judgment of tissue-engineered cartilage. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:1179–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hattori K, Takakura Y, Ohgushi H, Habata T, Uematsu K, Yamauchi J, Yamashita K, Fukuchi T, Sato M, Ikeuchi K. Quantitative ultrasound can assess the regeneration process of tissue-engineered cartilage using a complex between adherent bone marrow cells and a three-dimensional scaffold. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R552–R559. doi: 10.1186/ar1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Herrmann JM, Pitris C, Bouma BE, Boppart SA, Jesser CA, Stamper DL, Fujimoto JG, Brezinski ME. High resolution imaging of normal and osteoarthritic cartilage with optical coherence tomography. Journal of Rheumatology. 1999;26:627–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huisman A, Ploeger LS, Dullens HF, Jonges TN, Belien JA, Meijer GA, Poulin N, Grizzle WE, van Diest PJ. Discrimination between benign and malignant prostate tissue using chromatin texture analysis in 3-D by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Prostate. 2007;67:248–254. doi: 10.1002/pros.20507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ishihara M, Sato M, Sato S, Kikuchi T, Fujikawa K, Kikuchi M. Viscoelastic characterization of biological tissue by photoacoustic measurement. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics. 2003;42:556–558. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ishihara M, Sato M, Sato S, Kikuchi T, Mochida J, Kikuchi M. Usefulness of photoacoustic measurements for evaluation of biomechanical properties of tissue-engineered cartilage. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1234–1243. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johnstone B, Hering TM, Caplan AI, Goldberg VM, Yoo JU. In vitro chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells. Experimental Cell Research. 1998;238:265–272. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kafienah W, Cheung FL, Sims T, Martin I, Miot S, Von Ruhland C, Roughley PJ, Hollander AP. Lumican inhibits collagen deposition in tissue engineered cartilage. Matrix Biology. 2008;27:526–534. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kanai Y, Koopman P. Structural and functional characterization of the mouse Sox9 promoter: implications for campomelic dysplasia. Human Molecular Genetics. 1999;8:691–696. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.4.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kato S, Yamada H, Terada N, Masuda K, Lenz ME, Morita M, Yoshihara Y, Henmi O. Joint biomarkers in idiopathic femoral head osteonecrosis: comparison with hip osteoarthritis. Journal of Rheumatology. 2005;32:1518–1523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim M, Bi X, Horton WE, Spencer RG, Camacho NP. Fourier transform infrared imaging spectroscopic analysis of tissue engineered cartilage: histologic and biochemical correlations. J Biomed Opt. 2005;10:031105. doi: 10.1117/1.1922329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kiviranta P, Toyras J, Nieminen MT, Laasanen MS, Saarakkala S, Nieminen HJ, Nissi MJ, Jurvelin JS. Comparison of novel clinically applicable methodology for sensitive diagnostics of cartilage degeneration. Eur Cell Mater. 2007;13:46–55. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v013a05. discussion 55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Knauper V, Smith B, Lopez-Otin C, Murphy G. Activation of progelatinase B (proMMP-9) by active collagenase-3 (MMP-13) European Journal of Biochemistry. 1997;248:369–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Knudson C, Knudson W. Cartilage proteoglycans. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2001;12:69–78. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kotecha M, Klatt D, Magin RL. Monitoring cartilage tissue engineering using magnetic resonance spectroscopy, imaging, and elastography. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2013;19:470–484. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2012.0755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kundu K, Knight SF, Willett N, Lee S, Taylor WR, Murthy N. Hydrocyanines: a class of fluorescent sensors that can image reactive oxygen species in cell culture, tissue, and in vivo. Angewandte Chemie. International Ed. In English. 2009;48:299–303. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2007;89:780–785. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kurz B, Lemke AK, Fay J, Pufe T, Grodzinsky AJ, Schunke M. Pathomechanisms of cartilage destruction by mechanical injury. Ann Anat. 2005;187:473–485. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Laasanen MS, Toyras J, Vasara A, Saarakkala S, Hyttinen MM, Kiviranta I, Jurvelin JS. Quantitative ultrasound imaging of spontaneous repair of porcine cartilage. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2006;14:258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Laasanen MS, Toyras J, Vasara AI, Hyttinen MM, Saarakkala S, Hirvonen J, Jurvelin JS, Kiviranta I. Mechano-acoustic diagnosis of cartilage degeneration and repair. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-American Volume. 2003;85A:78–84. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200300002-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lareu RR, Arsianti I, Subramhanya HK, Yanxian P, Raghunath M. In vitro enhancement of collagen matrix formation and crosslinking for applications in tissue engineering: a preliminary study. Tissue Engineering. 2007;13:385–391. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lareu RR, Subramhanya KH, Peng Y, Benny P, Chen C, Wang Z, Rajagopalan R, Raghunath M. Collagen matrix deposition is dramatically enhanced in vitro when crowded with charged macromolecules: the biological relevance of the excluded volume effect. FEBS Letters. 2007;581:2709–2714. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Laurent D, Wasvary J, Yin JY, Rudin M, Pellas TC, O' Byrne E. Quantitative and qualitative assessment of articular cartilage in the goat knee with magnetization transfer imaging. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2001;19:1279–1286. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(01)00433-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee HY, Kopesky PW, Plaas A, Sandy J, Kisiday J, Frisbie D, Grodzinsky AJ, Ortiz C. Adult bone marrow stromal cell-based tissue-engineered aggrecan exhibits ultrastructure and nanomechanical properties superior to native cartilage. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2010;18:1477–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee Z, Dennis J, Alsberg E, Krebs MD, Welter J, Caplan A. Imaging stem cell differentiation for cell-based tissue repair. Methods Enzymol. 2012;506:247–263. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-391856-7.00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li LP, Herzog W. Arthroscopic evaluation of cartilage degeneration using indentation testing--influence of indenter geometry. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2006;21:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liukkonen J, Lehenkari P, Hirvasniemi J, Joukainen A, Viren T, Saarakkala S, Nieminen MT, Jurvelin JS, Toyras J. Ultrasound arthroscopy of human knee cartilage and subchondral bone in vivo. Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. 2014;40:2039–2047. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lopez O, Amrami KK, Manduca A, Ehman RL. Characterization of the dynamic shear properties of hyaline cartilage using high-frequency dynamic MR elastography. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2008;59:356–364. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lopez O, Amrami KK, Manduca A, Rossman PJ, Ehman RL. Developments in dynamic MR elastography for in vitro biomechanical assessment of hyaline cartilage under high-frequency cyclical shear. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2007;25:310–320. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lotjonen P, Julkunen P, Toyras J, Lammi MJ, Jurvelin JS, Nieminen HJ. Strain-dependent modulation of ultrasound speed in articular cartilage under dynamic compression. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2009;35:1177–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Love Z, Wang F, Dennis J, Awadallah A, Salem N, Lin Y, Weisenberger A, Majewski S, Gerson S, Lee Z. Imaging of mesenchymal stem cell transplant by bioluminescence and PET. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2007;48:2011–2020. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.043166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Love Z, Wang F, Dennis J, Awadallah A, Salem N, Lin Y, Weisenberger A, Majewski S, Gerson S, Lee Z. Imaging of mesenchymal stem cell transplant by bioluminescence and PET. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2007;48:2011–2020. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.043166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lyyra T, Jurvelin J, Pitkänen P, Väätäinen U, Kiviranta I. Indentation instrument for the measurement of cartilage stiffness under arthroscopic control. Medical Engineering & Physics. 1995;17:395–399. doi: 10.1016/1350-4533(95)97322-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ma PX, Langer R. Morphology and mechanical function of long-term in vitro engineered cartilage. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1999;44:217–221. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199902)44:2<217::aid-jbm12>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ma T, Qian X, Chiu CT, Yu M, Jung H, Tung YS, Shung KK, Zhou Q. High-resolution harmonic motion imaging (HR-HMI) for tissue biomechanical property characterization. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2015;5:108–117. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2014.11.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mackay AM, Beck SC, Murphy JM, Barry FP, Chichester CO, Pittenger MF. Chondrogenic differentiation of cultured human mesenchymal stem cells from marrow. Tissue Engineering. 1998;4:415–428. doi: 10.1089/ten.1998.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mak AF, Lai WM, Mow VC. Biphasic indentation of articular cartilage--I. Theoretical analysis. Journal of Biomechanics. 1987;20:703–714. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(87)90036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mansour JM, Gu DW, Chung CY, Heebner J, Althans J, Abdalian S, Schluchter MD, Liu Y, Welter JF. Towards the feasibility of using ultrasound to determine mechanical properties of tissues in a bioreactor. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2014;42:2190–2202. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1079-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mansour JM, Welter JF. Multimodal evaluation of tissue-engineered cartilage. J Med Biol Eng. 2013;33:1–16. doi: 10.5405/jmbe.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Martin I, Obradovic B, Treppo S, Grodzinsky AJ, Langer R, Freed LE, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Modulation of the mechanical properties of tissue engineered cartilage. Biorheology. 2000;37:141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Martinez-Sanchez A, Dudek KA, Murphy CL. Regulation of human chondrocyte function through direct inhibition of cartilage master regulator SOX9 by microRNA-145 (miRNA-145) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287:916–924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.302430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Matcher SJ. Practical aspects of OCT imaging in tissue engineering. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2011;695:261–280. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-984-0_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Matcher SJ. What can biophotonics tell us about the 3D microstructure of articular cartilage? Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2015;5:143–158. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2014.12.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mauck RL, Soltz MA, Wang CC, Wong DD, Chao PH, Valhmu WB, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Functional tissue engineering of articular cartilage through dynamic loading of chondrocyte-seeded agarose gels. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2000;122:252–260. doi: 10.1115/1.429656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.McCredie AJ, Stride E, Saffari N. Ultrasound elastography to determine the layered mechanical properties of articular cartilage and the importance of such structural characteristics under load. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2009;2009:4262–4265. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5334589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.McLauchlan GJ, Gardner DL. Sacral and iliac articular cartilage thickness and cellularity: relationship to subchondral bone end-plate thickness and cancellous bone density. Rheumatology. 2002;41:375–380. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.McNary SM, Athanasiou KA, Reddi AH. Engineering lubrication in articular cartilage. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2012;18:88–100. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2011.0394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Melrose J, Isaacs MD, Smith SM, Hughes CE, Little CB, Caterson B, Hayes AJ. Chondroitin sulphate and heparan sulphate sulphation motifs and their proteoglycans are involved in articular cartilage formation during human foetal knee joint development. Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 2012;138:461–475. doi: 10.1007/s00418-012-0968-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mengshol JA, Vincenti MP, Brinckerhoff CE. IL-1 induces collagenase-3 (MMP-13) promoter activity in stably transfected chondrocytic cells: requirement for Runx-2 and activation by p38 MAPK and JNK pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4361–4372. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.21.4361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mow VC, Kuei SC, Lai WM, Armstrong CG. Biphasic creep and stress relaxation of articular cartilage in compression? Theory and experiments. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 1980;102:73–84. doi: 10.1115/1.3138202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mow VC, Ratcliffe A, Rosenwasser MP, Buckwalter JA. Experimental studies on repair of large osteochondral defects at a high weight bearing area of the knee joint: A tissue engineering study. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 1991;113:198–207. doi: 10.1115/1.2891235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Muller J, Benz K, Ahlers M, Gaissmaier C, Mollenhauer J. Hypoxic conditions during expansion culture prime human mesenchymal stromal precursor cells for chondrogenic differentiation in three-dimensional cultures. Cell Transplantation. 2011;20:1589–1602. doi: 10.3727/096368910X564094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Murata K, Yoshitomi H, Tanida S, Ishikawa M, Nishitani K, Ito H, Nakamura T. Plasma and synovial fluid microRNAs as potential biomarkers of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R86. doi: 10.1186/ar3013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Na K, Kim S, Sun BK, Woo DG, Yang HN, Chung HM, Park KH. Bioimaging of dexamethasone and TGF beta-1 and its biological activities of chondrogenic differentiation in hydrogel constructs. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, Part A. 2008;87:283–289. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nakano T, Sim JS. A study of the chemical composition of the proximal tibial articular cartilage and growth plate of broiler chickens. Poultry Science. 1995;74:538–550. doi: 10.3382/ps.0740538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nebelung S, Brill N, Marx U, Quack V, Tingart M, Schmitt R, Rath B, Jahr H. Three-dimensional imaging and analysis of human cartilage degeneration using Optical Coherence Tomography. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2015;33:651–659. doi: 10.1002/jor.22828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Neu CP, Arastu HF, Curtiss S, Reddi AH. Characterization of engineered tissue construct mechanical function by magnetic resonance imaging. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2009;3:477–485. doi: 10.1002/term.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Neu CP, Hull ML, Walton JH, Buonocore MH. MRI-based technique for determining nonuniform deformations throughout the volume of articular cartilage explants. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2005;53:321–328. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Neu CP, Walton JH. Displacement encoding for the measurement of cartilage deformation. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2008;59:149–155. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nieminen HJ, Saarakkala S, Laasanen MS, Hirvonen J, Jurvelin JS, Töyräs J. Ultrasound attenuation in normal and spontaneously degenerated articular cartilage. Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. 2004;30:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nieminen HJ, Ylitalo T, Karhula S, Suuronen JP, Kauppinen S, Serimaa R, Haeggstrom E, Pritzker KP, Valkealahti M, Lehenkari P, Finnila M, Saarakkala S. Determining collagen distribution in articular cartilage using contrast-enhanced micro-computed tomography. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nieminen HJ, Zheng Y, Saarakkala S, Wang Q, Toyras J, Huang Y, Jurvelin J. Quantitative assessment of articular cartilage using high-frequency ultrasound: research findings and diagnostic prospects. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2009;37:461–494. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v37.i6.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Niu HJ, Wang Q, Wang YX, Li DY, Fan YB, Chen WF. Ultrasonic reflection coefficient and surface roughness index of OA articular cartilage: relation to pathological assessment. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Obradovic B, Carrier RL, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Freed LE. Gas exchange is essential for bioreactor cultivation of tissue engineered cartilage. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1999;63:197–205. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19990420)63:2<197::aid-bit8>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Obradovic B, Carrier RL, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Freed LE. Gas exchange is essential for bioreactor cultivation of tissue engineered cartilage. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 1999;63:197–205. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19990420)63:2<197::aid-bit8>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ollier M, Maurizis JC, Nicolas C, Bonafous J, de Latour M, Veyre A, Madelmont JC. Joint scintigraphy in rabbits with 99mtc-N-[3-(triethylammonio)propyl]-15ane-N5, a new radiodiagnostic agent for articular cartilage imaging. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2001;42:141–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ophir J, Alam SK, Garra BS, Kallel F, Konofagou EE, Krouskop T, Merritt CRB, Righetti R, Souchon R, Srinivasan S, Varghese T. Elastography: Imaging the elastic properties of soft tissues with ultrasound. Journal of Medical Ultrasonics. 2002;29:155–171. doi: 10.1007/BF02480847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Palmer AW, Guldberg RE, Levenston ME. Analysis of cartilage matrix fixed charge density and three-dimensional morphology via contrast-enhanced microcomputed tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19255–19260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606406103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Palukuru UP, McGoverin CM, Pleshko N. Assessment of hyaline cartilage matrix composition using near infrared spectroscopy. Matrix Biol. 2014;38:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pattappa G, Heywood HK, de Bruijn JD, Lee DA. The metabolism of human mesenchymal stem cells during proliferation and differentiation. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2011;226:2562–2570. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Payne KA, Lee HH, Haleem AM, Martins C, Yuan Z, Qiao C, Xiao X, Chu CR. Single intra-articular injection of adeno-associated virus results in stable and controllable in vivo transgene expression in normal rat knees. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2011;19:1058–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Pellaumail B, Watrin A, Loeuille D, Netter P, Berger G, Laugier P, Saied A. Effect of articular cartilage proteoglycan depletion on high frequency ultrasound backscatter. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002;10:535–541. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Plaas AH, Wong-Palms S, Roughley PJ, Midura RJ, Hascall VC. Chemical and immunological assay of the nonreducing terminal residues of chondroitin sulfate from human aggrecan. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:20603–20610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Potter K, Kidder LH, Levin IW, Lewis EN, Spencer RG. Imaging of collagen and proteoglycan in cartilage sections using Fourier transform infrared spectral imaging. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:846–855. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)44:4<846::AID-ANR141>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Prologo JD, Pirasteh A, Tenley N, Yuan L, Corn D, Hart D, Love Z, Lazarus HM, Lee Z. Percutaneous Image-guided Delivery for the Transplantation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Setting of Degenerated Intervertebral Discs. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:1084–1088. e1086. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Puetzer JL, Petitte JN, Loboa EG. Comparative review of growth factors for induction of three-dimensional in vitro chondrogenesis in human mesenchymal stem cells isolated from bone marrow and adipose tissue. Tissue eng. Part B. 2010;16:435–444. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2009.0705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]