Abstract

Invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells are a subset of T lymphocytes that recognize lipid ligands presented by monomorphic CD1d. Human iNKT T cell receptor (TCR) is largely composed of invariant Vα24 (Vα24i) TCRα chain and semi-variant Vβ11 TCRβ chain, where complementarity-determining region (CDR)3β is the sole variable region. One of the characteristic features of iNKT cells is that they retain autoreactivity even after the thymic selection. However, the molecular features of human iNKT TCR CDR3β sequences that regulate autoreactivity remain unknown. Since the numbers of iNKT cells with detectable autoreactivity in peripheral blood is limited, we introduced the Vα24i gene into peripheral T cells and generated a de novo human iNKT TCR repertoire. By stimulating the transfected T cells with artificial antigen presenting cells (aAPCs) presenting self-ligands, we enriched strongly autoreactive iNKT TCRs and isolated a large panel of human iNKT TCRs with a broad range autoreactivity. From this panel of unique iNKT TCRs, we deciphered three CDR3β sequence motifs frequently encoded by strongly-autoreactive iNKT TCRs: a VD region with 2 or more acidic amino acids, usage of the Jβ2-5 allele, and a CDR3β region of 13 amino acids in length. iNKT TCRs encoding 2 or 3 sequence motifs also exhibit higher autoreactivity than those encoding 0 or 1 motifs. These data facilitate our understanding of the molecular basis for human iNKT cell autoreactivity involved in immune responses associated with human disease.

Keywords: iNKT, autoreactivity, TCR, CDR3β

1. Introduction

Invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells are immune modulators that bridge innate and adaptive immunity. Upon stimulation, iNKT cells rapidly produce cytokines and chemokines and regulate diverse immune responses associated with infections, autoimmune diseases, allergies, cancer, and metabolism [1-4]. Human iNKT T cell receptors (TCRs) largely comprise the invariable Vα24 TCRα chain and a semi-variable Vβ11 TCRβ chain, in which CDR3β is the only variable region of the TCR [5-7]. The TCRs recognize lipid ligands presented on the monomorphic non-classical major histocompatibility complex (MHC) CD1d. All iNKT TCRs recognize the marine sponge-derived glycolipid α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer), which thereby serves as a prototypic iNKT cell ligand [8].

Several phospholipids, β-linked glycolipids, and plasmalogen have been identified as self-lipids recognized by iNKT cells [9-12]. The molecule β-glucopyranosylceramide (β-GlcCer) was reported as a potent self-ligand for both mouse and human iNKT cells that accumulates in response to microbial infection [9]. Recent findings have indicated that the antigenic fraction of commercially available β-GlcCer, which was used in many published studies as well as this study, is likely to be attributed to the rare constituent α-GlcCer [13, 14]. Lyso-phosphatidylcholine (LPC), which is elevated in inflammation responses, was shown to activate human iNKT cells [10]. C16-alkanyl-lysophosphatidic acid (eLPA) and C16-lysophosphatidylethanolamine (pLPE) were derived from the peroxisome and stimulated thymic and splenic iNKT cells [11].

Although peripheral iNKT cells undergo negative selection in the thymus, it is well known that these cells retain autoreactivity toward lipid self-ligands [15-19]. The self-recognition of iNKT cells is implied by their activation status and functional activity in vivo. Human peripheral iNKT cells require continued engagement by CD1d/self-ligand complexes to maintain epigenetic Ifn-γ locus modification that allows rapid IFN-γ production upon TCR engagement. This weak self-ligand stimulation primes iNKT cells to serve as rapid responders, characteristic of innate immunity [19]. It is also reported that iNKT cells become activated and produce cytokines through the recognition of CD1d-restricted self-ligands when combined with inflammatory cytokines mediated by infectious agents [3, 20]. These reports suggest that self-recognition of iNKT cells plays an important role in the rapid innate responses to eliminate microbes. Other researchers have reported that the numbers of iNKT cells are reduced in patients with systemic lupus erythematous (SLE), in whom the CD1d expression level on B cells is downregulated. The iNKT cell numbers are recovered after normal CD1d-expressing B cells repopulate the peripheral blood following rituximab treatment, suggesting that self-ligand presentation by CD1d+ B cells may contribute to the maintenance of iNKT cells in humans [21]. These observations underscore the biological significance of iNKT cell autoreactivity in the periphery.

Elucidating how the CDR3β sequences, which are the sole variable region of human iNKT TCRs, impact the recognition of diverse self-ligands is key to understanding the nature of iNKT cell autoreactivity. However, addressing these important questions has been hampered by the difficulty in preparing a large iNKT TCR repertoire with a wide range of autoreactivity. The paucity of natural iNKT cells with strong autoreactivity in the periphery due to thymic negative selection [22], and the generally limited number of iNKT cells in PBMC restrict our ability to study a comprehensive repertoire of iNKT TCRs [23]. In this paper, we have generated a de novo repertoire of autoreactive iNKT TCRs and isolated a large panel of human iNKT TCRs with a broad range of autoreactivity. By analyzing the structural avidity of SupT1 cells transduced with these clonotypic TCRs for different self-ligand tetramers, we found 3 CDR3β amino acid sequence motifs that are highly associated with strong autoreactivity of human iNKT TCRs: a VD region with 2 or more acidic amino acids, usage of the Jβ2-5 allele, and a CDR3β region of 13 amino acids in length. Our findings elucidated the structural basis of human iNKT TCR autoreactivity in further detail.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained from healthy donors. Institutional review board approval and appropriate informed consent were obtained. All cell lines were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultured according to the provided instructions.

2.2. Reagents

α-Galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) was purchased from Axxora (San Diego, CA); β-glucopyranosylceramide C24:1 (β-GlcCer) [9], lyso-phosphatidylcholine (18:1) (LPC) [10], C16-alkanyl-lysophosphatidic acid (eLPA) and C16-lysophosphatidylethanolamine (pLPE) [11] were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Recombinant human IL-2 was purchased from Novartis (New York, NY).

2.3. Generation of CD1d-artificial antigen-presenting cells (aAPC)

K562-based CD1d-artificial antigen-presenting cells (aAPC) were generated using a retrovirus system based on 293GPG packaging cells as previously described [24, 25]. Briefly, K562, which is deficient for the HLA-class I, II and CD1d molecules, was sequentially transduced with human CD80, CD83, and CD1d. Triple-positive cells were isolated by magnetic bead-guided sorting following mAb staining.

2.4. Expansion of CD1d-restricted iNKT cells

Human CD3+ T cells purified from healthy donors were plated in 24-well plates at a density of 2×106 cells/well in RPMI 1640 with 10% human AB serum. Then, aAPCs pulsed with DMSO or α-GalCer in DMSO were irradiated (200 Gray) and added to the responder cells at a responder to stimulator ratio of 20:1 (day 0). The T cells were restimulated every 7 days and supplemented with 100 IU/ml of IL-2 every three days.

2.5. Flow cytometry analysis

The following mAbs recognizing the indicated antigens were used: human Vα24 TCRα chain and Vβ11 TCRβ chain from Beckman Coulter (Mississauga, Canada); human CD1d, TCRαβ, CD3, CD80, CD83, INF-γ, IL-4 and isotype controls from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA); human ICAM-1 and LFA-3 from Ancell (Bayport, MN); Biotinylated human CD1d monomers, both unloaded and loaded with the α-GalCer analog PBS-57, were kindly provided by the NIH Tetramer Core Facility. Unloaded monomers were produced in HEK293 cells and therefore presented HEK293-derived endogenous ligand(s). Where indicated, unloaded tetramers were loaded with β-GlcCer, LPC, pLPE, or eLPA according to the protocol provided by the Tetramer Core Facility. The loading of each ligand was performed immediately prior to use. Unloaded or loaded monomers were tetramerized with streptavidin conjugated to PE (Life Technologies). To determine the structural avidity, iNKT TCR-positive cells were stained with graded concentrations of CD1d tetramer. The EC50 was defined as the tetramer dose that resulted in 50% of the maximal tetramer staining level. All transfectants were simultaneously stained with freshly multimerized CD1d monomers. All % staining values were normalized to the Vβ11 TCRβ chain expression levels (%). The surface molecule staining and subsequent flow cytometry analysis were performed as described elsewhere [24].

2.6. cDNAs

Full-length cDNAs encoding the invariant Vα24 (Vα24i) TCRα and Vβ11 TCRβ genes were molecularly cloned via RT-PCR using Vα24 and Vβ11-specific primers, respectively. Codon-optimized TCR cDNAs were produced by Thermo Fisher Scientific (Burlingame, CA). The cDNAs were cloned into pMX or pMX/IRES-EGFP vector to transduce all cell lines and primary human T cells [26]. Nucleotide sequencing was performed at the Centre for Applied Genomics, The Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto, Canada). CDR3β sequences were defined as the sequence from the first Ala to the amino acid before the last Phe according to IMGT (http://www.imgt.org/). The CDR3β amino acid sequences of the mutated Vβ11 chains are as follows: Cl.2110 (2 D/E→1 D/E) CASSEYMAGGEKLFF; Cl.1089 (J2-5→J1-1) CASSDLPTEAFF; Cl.2117 (13 aa→12 aa) CASSPGGHGYEQYF; Cl.1050 (1 D/E, J1-6→2 D/E, J2-5) CASSESATGDETQYF; Cl.2104 (1 D/E, 10 aa→2 D/E, 13 aa) CASSEFDSVGETQYF; and Cl.3092 (J2-7, 12 aa→J2-5, 13 aa) CASSEFGGQDETQYF. The 5th and/or the last amino acid positions of CDR3β were mainly substituted. For insertion, similar amino acid sequences that were found in other clones on Table 1 were used.

Table 1.

Sequence information and structural avidities of the 54 isolated human iNKT TCRs

| Clone | VD sequence | J sequence | Structural avidity determined by unloaded tetramer staining (%) | Structural avidity determined by β-GlcCer tetramer staining (%) | Structural avidity determined by LPC tetramer staining (%) | Structural avidity determined by pLPE tetramer staining (%) | ≥2 D/E | J2-5 | 13 aa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cl.3062 | CASSEYRL | QETQYF | 95.9 | 98.7 | 89.4 | 72.6 | No | Yes | No |

| Cl.3096 | CASSELYTGGD | EQFF | 95.9 | 100.0 | 94.7 | 84.8 | Yes | No | Yes |

| Cl.3078 | CASSEYGTL | QETQYF | 93.4 | 98.6 | 70.5 | 82.5 | No | Yes | Yes |

| Cl.3014 | CASSEFGQSAD | EQFF | 93.4 | 97.5 | 85.8 | 72.6 | Yes | No | Yes |

| Cl.1140 | CASSEWAGG | QETQYF | 93.2 | 99.2 | 96.4 | 56.7 | No | Yes | Yes |

| Cl.2037 | CASSEFDGGQ | ETQYF | 91.2 | 94.7 | 52.6 | 50.5 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cl.2118 | CASSGYQGGG | ETQYF | 90.4 | 93.8 | 30.1 | 39.3 | No | Yes | Yes |

| Cl.2110 | CASSEYMEGG | EKLFF | 89.8 | 95.3 | 35.7 | 47.5 | Yes | No | Yes |

| Cl.1089 | CASSDLP | ETQYF | 85.5 | 91.3 | 33.7 | 22.7 | No | Yes | No |

| Cl.3020 | CASSFGG | ETQYF | 80.2 | 80.7 | 12.8 | 11.5 | No | Yes | No |

| Cl.2113 | CASSTGGAD | EKLFF | 66.5 | 7.6 | 2.3 | 0.4 | No | No | No |

| Cl.2106 | CASSEWGRT | QETQYF | 62.5 | 88.2 | 17.8 | 31.7 | No | Yes | Yes |

| Cl.3010a | CASSGLLTGP | DTQYF | 50.6 | 81.9 | 28.0 | 9.4 | No | No | Yes |

| Cl.2119 | CASSEPTGLG | TDTQYF | 45.7 | 33.8 | 1.4 | 1.9 | No | No | No |

| Cl.2117 | CASSPIGGHG | YEQYF | 45.3 | 38.0 | 2.6 | 0.9 | No | No | Yes |

| Cl.1008 | CASSDLMGPDN | YEQYF | 41.8 | 41.6 | 11.4 | 1.4 | Yes | No | No |

| Cl.2121 | CASSEYMEAGIP | TDTQYF | 39.7 | 11.7 | 1.5 | 1.2 | Yes | No | No |

| Cl.2033 | CASSEAPWRD | SGNTIYF | 38.7 | 61.3 | 2.5 | 5.6 | Yes | No | No |

| Cl.3017 | CASSPRDRWH | EQYF | 36.9 | 97.4 | 72.2 | 43.0 | No | No | No |

| Cl.2001a | CASSEYFAGFN | EQYF | 26.0 | 76.2 | 11.1 | 11.6 | No | No | Yes |

| Cl.2050 | CASSEYES | TNEKLFF | 21.0 | 12.6 | 4.2 | 1.8 | Yes | No | Yes |

| Cl.3016 | CASSDLGLAGVI | EQFF | 13.7 | 75.9 | 7.0 | 6.1 | No | No | No |

| Cl.1083a | CASSEWGT | TNEKLFF | 10.3 | 85.9 | 3.6 | 13.9 | No | No | Yes |

| Cl.1024a | CASSDRLAG | DTQYF | 9.5 | 8.7 | 1.7 | 0.8 | No | No | No |

| Cl.2128 | CASSGTGGAFD | EQFF | 9.1 | 4.9 | 3.2 | 1.7 | No | No | Yes |

| Cl.2048 | CASSESLAGG | YNEQFF | 8.4 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 0.4 | No | No | No |

| Cl.2042a | CASSEWEDI | TDTQYF | 7.6 | 82.5 | 9.2 | 4.7 | Yes | No | Yes |

| Cl.3089 | CASSEYRRRSG | EKLFF | 5.8 | 12.0 | 2.6 | 2.4 | No | No | No |

| Cl.3103 | CASSVPLRD | YEQYF | 5.5 | 23.4 | 1.0 | 1.4 | No | No | No |

| Cl.3106 | CASSELLRGQGR | TGELFF | 3.0 | 52.4 | 4.5 | 2.7 | No | No | No |

| Cl.1034b | CASSDGF | TDTQYF | 2.7 | 1.4 | 3.4 | 1.1 | No | No | No |

| Cl.2104b | CASSESV | ETQYF | 2.7 | 11.3 | 3.9 | 1.2 | No | Yes | No |

| Cl.3091 | CASSEGTAG | TDTQYF | 1.8 | 37.2 | 6.8 | 3.8 | No | No | Yes |

| Cl.1011b | CASTPSGGWSS | DTQYF | 0.8 | 0.9 | 2.9 | 0.8 | No | No | No |

| Cl.2100 | CASSEGTGP | NSPLHF | 0.6 | 0.2 | 8.0 | 0.3 | No | No | Yes |

| Cl.3092 | CASSEGGQD | YEQYF | 0.6 | 3.2 | 6.6 | 1.8 | Yes | No | No |

| Cl.3074a | CASSDRA | NEQFF | 0.3 | 52.6 | 7.6 | 11.1 | No | No | No |

| Cl.1045b | CASSEAGSG | EKLFF | 0.3 | 0.4 | 2.9 | 0.5 | No | No | No |

| Cl.1050b | CASSESATGF | SPLHF | 0.3 | 0.4 | 1.7 | 1.5 | No | No | Yes |

| Cl.3115b | CASSRGGY | TEAFF | 0.3 | 0.6 | 3.8 | 1.3 | No | No | No |

| Cl.3007 | CASRYYSVQGR | TDTQYF | 0.2 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 1.0 | No | No | No |

| Cl.1096 | CASSAWDG | YEQYF | 0.2 | 14.2 | 3.5 | 2.2 | No | No | No |

| Cl.3049b | CASTPRKGTDV | GNTIYF | 0.2 | 0.7 | 5.6 | 1.6 | No | No | No |

| Cl.2133b | CASRGQGLG | EQYF | 0.1 | 0.8 | 3.5 | 0.6 | No | No | No |

| Cl.3015 | CASSEGW | YEQYF | 0.1 | 6.1 | 3.0 | 1.2 | No | No | No |

| Cl.2004 | CASTSL | ETQYF | 0.1 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 0.4 | No | Yes | No |

| Cl.3072b | CASSESGGS | TEAFF | 0.1 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 2.5 | No | No | No |

| Cl.3011 | CASSGTV | TEAFF | 0.1 | 0.5 | 3.6 | 1.0 | No | No | No |

| Cl.3046b | CASSEMGQGV | YTF | 0.1 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 1.8 | No | No | No |

| Cl.3068a | CASSEALI | LFF | 0.1 | 28.7 | 2.9 | 3.6 | No | No | No |

| Cl.2016b | CASSAPLAGH | YEQYF | 0.1 | 10.9 | 5.6 | 0.2 | No | No | Yes |

| Cl.3041b | CASSRGGFD | EQYF | 0.1 | 0.9 | 8.8 | 1.2 | No | No | No |

| Cl.2025b | CASSEL | TDTQYF | 0.1 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 0.7 | No | No | No |

| Cl.3012a | CASSRGGG | TEAFF | 0.1 | 4.0 | 1.3 | 1.7 | No | No | No |

Vβ11+ TCR clones obtained by stimulation with either unloaded or α-GalCer-loaded aAPC.

Clones obtained by stimulation with α-GalCer-loaded aAPC but not unloaded aAPC. Unlabeled clones were isolated by stimulation with unloaded aAPC but not α-GalCer-loaded aAPC. Structural avidities determined via staining with unloaded, β-GlcCer, LPC, and pLPE tetramers at the respective concentrations of 5, 10, 10, and 5 μg/ml are depicted. The loading of each ligand was performed immediately prior to use, and all 54 transfectants were stained simultaneously to minimize experimental variations. All % staining values were normalized to the Vβ11 TCRβ chain expression levels. The presence or absence of 2 or more aspartic and/or glutamic amino acids in a VD region (≥2 D/E), the Jβ gene J2-5, and/or a 13-amino-acid (aa) CDR3β region (13 aa from the first Ala to an amino acid before the last Phe) is also shown. CDR3β sequences were defined according to IMGT (http://www.imgt.org/).

2.7. Generation of TCR transfectants

Using the 293GPG-based retrovirus system, the Vα24 TCRα gene was transduced into TCR α−β+ SupT1 cells, and Vα24-positive SupT1 cells were isolated as CD3+ T cells. Established Vα24-positive SupT1 cells were further transduced with various clonotypic Vβ11 TCRβ genes. Vα24/Vβ11 double-positive cells were purified with an anti-Vβ11 mAb (purity >95%) and used for all assays. Primary human CD3+ T cells were initially activated with anti-CD3/CD28 mAbs, treated with IL-2, and retrovirally transduced with TCR genes using PG13 packaging cells. Transduction rate of Vα24i TCRα gene ranges from 15-25% of total T cells. Expression of introduced TCR genes is maintained at least 3 weeks post transduction, as previously demonstrated in similar experiments using the same retrovirus vector and packaging cell line [26, 27].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 5.0d and JMP Pro 10 software. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare two variables (Fig. 4A and B, and Fig. 5). Stepwise multiple regression analysis was used to identify sequence motifs associated with strong iNKT TCR autoreactivity (Fig. 5). A simple linear regression analysis was employed to assess the associations between two independent variables (Fig. 3C). R2 values of ≥0.6 were considered to indicate linear correlation. Non-parametric Spearman's rank correlation coefficients were calculated in Fig.4 C. R values of ≥0.7 were considered to indicate correlation. Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis analysis followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test was used to compare three variables (Fig. 6). All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

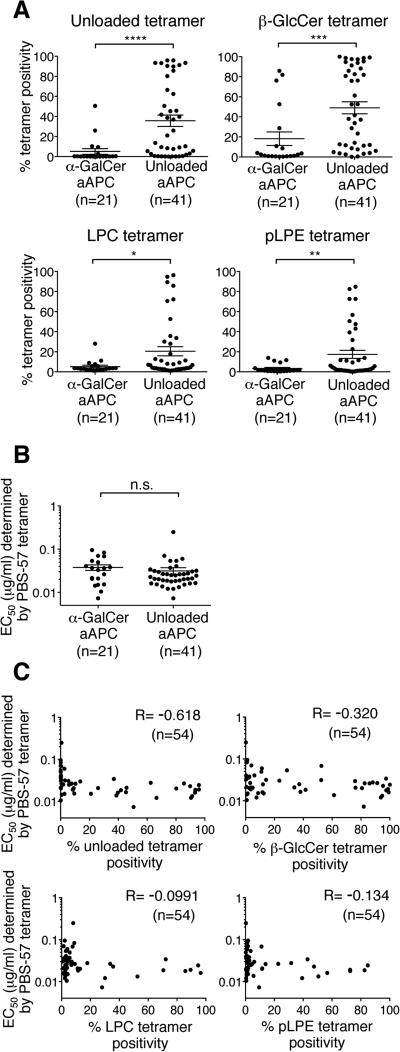

Figure 4. Unloaded aAPC stimulation expands Vα24i TCRα gene-transduced T cells with higher autoreactivity.

(A and B) The structural avidities for the unloaded, β-GlcCer, LPC, and pLPE tetramers shown in Table 1 (A) and the PBS-57 tetramer (B) were compared in iNKT TCR-expressing SupT1 cells cloned after α-GalCer-loaded or unloaded aAPC stimulation. Note that 8 TCRs were shared between the TCRs obtained from α-GalCer-loaded or unloaded aAPC stimulation. The data represent the means ± SEM of the indicated clones. n.s., not significant; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. (C) Correlations of the structural avidities for PBS-57 with unloaded tetramers (top left), PBS-57 with β-GlcCer tetramers (top right), PBS-57 with LPC tetramers (bottom left), and PBS-57 with pLPE tetramers (bottom right) of the 54 transfectants are shown. Spearman's rank correlation coefficients are shown for each plot. The data shown are representative of 2 independent experiments.

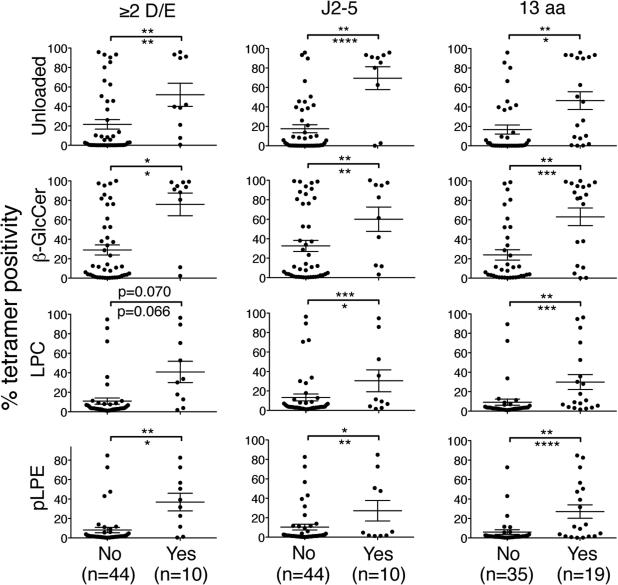

Figure 5. Three CDR3β amino acid sequence motifs are independently associated with high reactivity for self-ligand tetramers.

The structural avidities of SupT1 transfectants for the unloaded, β-GlcCer, LPC, and pLPE tetramers shown in Table 1 were compared based on the presence and absence of one of the following three CDR3β amino acid sequence motifs: a VD region with 2 or more aspartic or glutamic acid residues (≥2 D/E), usage of Jβ2-5, and CDR3β of 13 amino acids in length (13 aa). The data represent the means ± SEM in each group. The asterisks above and below the bars indicate the p values determined in a univariate analysis using the Mann-Whitney U test and a multivariate analysis (R2=0.54), respectively. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001

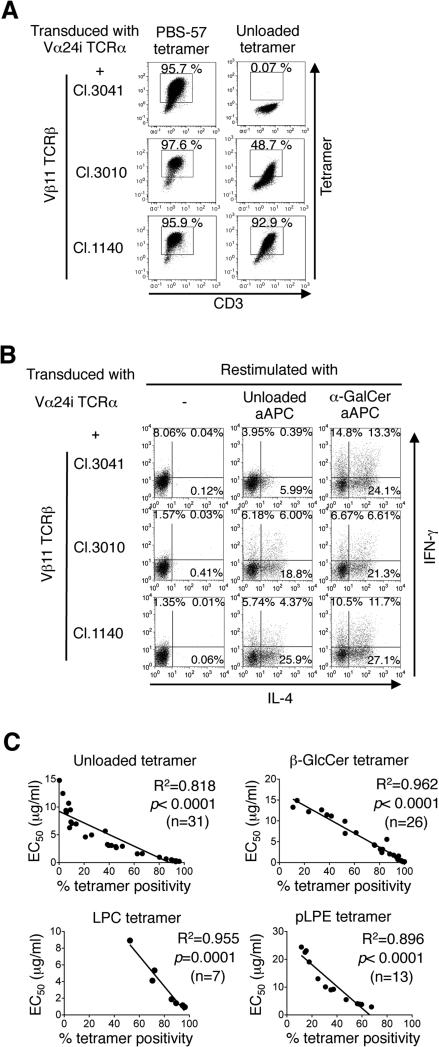

Figure 3. A large panel of iNKT TCRs with a broad range of autoreactivity were isolated and reconstituted.

(A) Fifty-four Vβ11 TCRβ genes were cloned from the Vα24i TCRα-transduced tetramer+ cells shown in Fig. 1E and individually reconstituted in SupT1 cells along with the Vα24i TCRα gene. Data for staining with unloaded and PBS-57 tetramer (5 μg/ml) of three representative transfectants (Cl.3041, Cl.3010, and Cl.1140) are shown. Tetramer staining of the remaining 51 transfectants is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1A and B. (B) Along with the Vα24i TCRα gene, peripheral CD4+ T cells were transduced with one of the three Vβ11 TCRβ genes described above and expanded by α-GalCer-loaded aAPC. Three days after the stimulation, the T cells were restimulated with unloaded or α-GalCer-loaded aAPC, and IFN-γ and IL-4 production were examined by intracellular cytokine staining. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (C) All SupT1 transfectants were additionally stained with the β-GlcCer, LPC, and pLPE tetramers at graded concentrations. Correlations between the EC50 and % staining as determined with the unloaded, β-GlcCer, LPC, and pLPE tetramers at respective concentrations of 5, 10, 10, and 5 μg/ml are shown for the SupT1 transfectants with calculable EC50 values. A simple linear regression analysis was conducted. All transfectants were simultaneously stained with freshly multimerized CD1d monomers. All % staining values were normalized to the Vβ11 TCRβ chain expression levels (%).

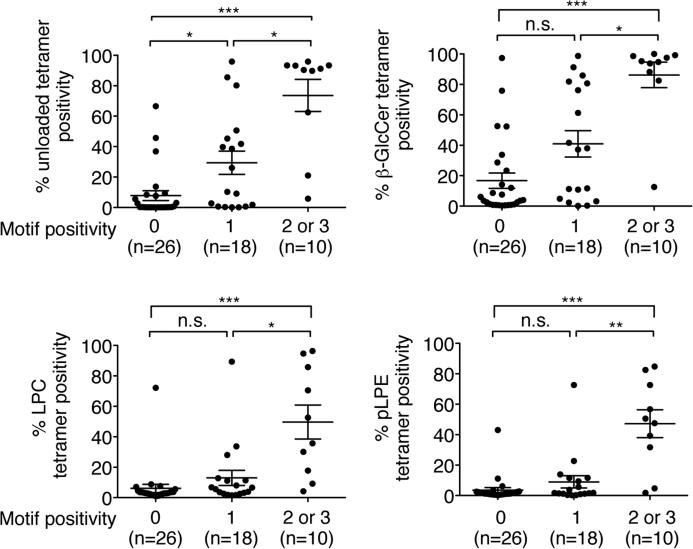

Figure 6. iNKT TCRs encoding 2 or 3 sequence motifs demonstrate higher autoreactivity than those encoding 0 or 1 sequence motif.

The structural avidities of the SupT1 transfectants for 4 different self-ligand tetramers depicted in Table 1 were compared based on the encoded number of the 3 CDR3β sequence motifs. n.s., not significant; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, Kruskal-Wallis analysis followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test.

3. Results

3.1. Generation of a de novo iNKT TCR repertoire

Peripheral iNKT cells were positively stained with human CD1d tetramer loaded with the α-GalCer analogue PBS-57 (PBS-57 tetramer), but were not stained with an unloaded tetramer that presented HEK293 cell-derived self-ligands (Fig. 1A). To expand the iNKT cells, we generated K562-based artificial antigen-presenting cells (aAPC) that expressed human CD1d and costimulatory molecules (Fig. 1B) [24, 25]. Although the α-GalCer-loaded aAPC could expand iNKT cells, unloaded aAPC expressing K562-derived endogenous ligands failed to expand peripheral iNKT cells (Fig. 1C). These data suggest that the frequency of human primary iNKT cells with structural or functional avidity detectable with these commonly used assays is low. The low prevalence of primary iNKT cells with detectable autoreactivity would make it difficult to isolate a large panel of human clonotypic iNKT cells with a broad range of autoreactivity.

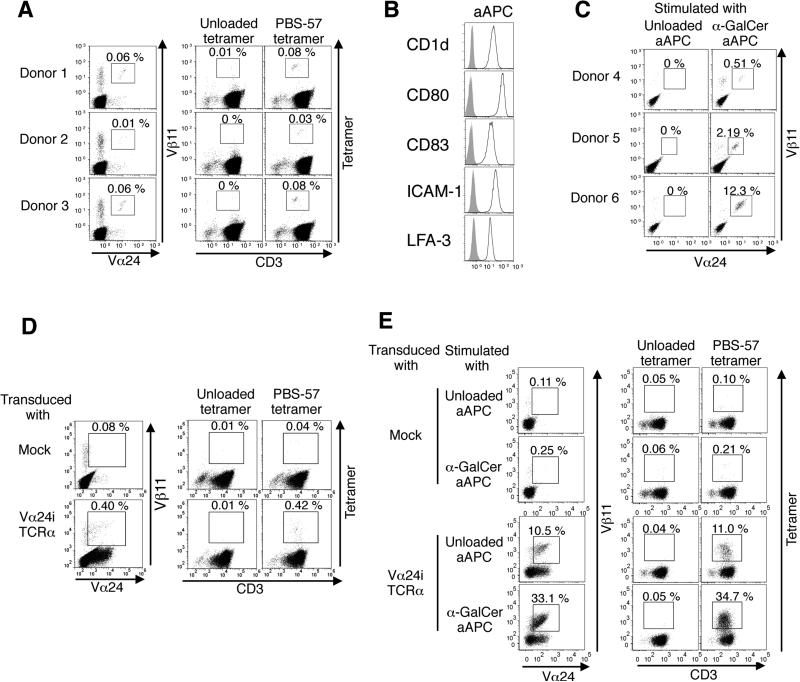

Figure 1. Transduction of the Vα24i TCRα gene into primary human T cells generates a de novo iNKT TCR repertoire with a broad range of autoreactivity.

(A) Peripheral mononuclear cells from 3 healthy donors are stained with anti-Vα24/Vβ11 mAbs and human CD1d tetramers either unloaded or loaded with the α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) analog PBS-57. (B) The surface expression levels of indicated molecules on K562-based CD1d+ artificial antigen-presenting cells (aAPC) were analyzed. (C) Peripheral CD3+ T cells were purified from 3 healthy donors and stimulated with unloaded or α-GalCer-loaded aAPC. iNKT cells were stained with anti-Vα24/Vβ11 mAbs. (D) Peripheral T cells were transduced with vector alone (mock) or the Vα24i TCRα gene and stained with anti-Vα24/Vβ11 mAbs and either unloaded or PBS-57-loaded tetramers (5 μg/ml). Data are representative of 3 donors. (E) The Vα24i TCRα gene-transduced T cells were stimulated by unloaded or α-GalCer-loaded aAPC and stained with anti-Vα24/Vβ11 mAbs or the indicated tetramers (5 μg/ml). Data are representative of 3 donors.

To meet this challenge, we capitalized on the fact that during development, the TCRβ chain repertoires of both iNKT and conventional T cells derive from common double-positive thymocytes [28, 29]. We speculated that the peripheral MHC-restricted β chain repertoire of conventional T cells should contain at least some β chains that are deleted during CD1d-mediated thymic selection. To create a de novo human iNKT TCR repertoire we transduced the invariant Vα24 (Vα24i) TCRα gene into human peripheral T cells. Similar methods were used previously to generate novel tumor-specific TCR repertoires with a wide range of affinity [26, 27]. The proportion of PBS-57-loaded CD1d tetramer-positive cells substantially increased, indicating the retrieval of a novel iNKT TCR repertoire using this approach (Fig. 1D). In contrast to the results observed for peripheral iNKT cells (Fig. 1C) or mock-transduced peripheral T cells, stimulation with not only α-GalCer-loaded aAPC, but also unloaded aAPC enriched the population of PBS-57 tetramer-positive T cells following the introduction of Vα24i TCRα gene (Fig. 1E). The expanded tetramer-positive T cells expressed Vα24+ Vβ11+ TCRs (Fig. 2A). When EGFP-tagged Vα24i TCRα gene was transduced, most of the expanded tetramer-positive T cells were EGFP positive (Fig. 2B). Therefore, the vast majority of these expanded tetramer-positive T cells were derived from Vα24i TCRα-transduced Vβ11+ T cells. The TCR expression levels of the primary and Vα24i TCRα-transduced T cells were comparable, indicating that the transduction did not lead to overexpression of surface TCRs (Fig. 2C). These data suggest that Vα24i TCRα gene transduction forced a subset of, if not all, Vβ11+ T cells to express autoreactive iNKT TCRs and acquire functional avidity sufficient to induce proliferation in response to self-ligands presented by CD1d molecules on K562-derived aAPC.

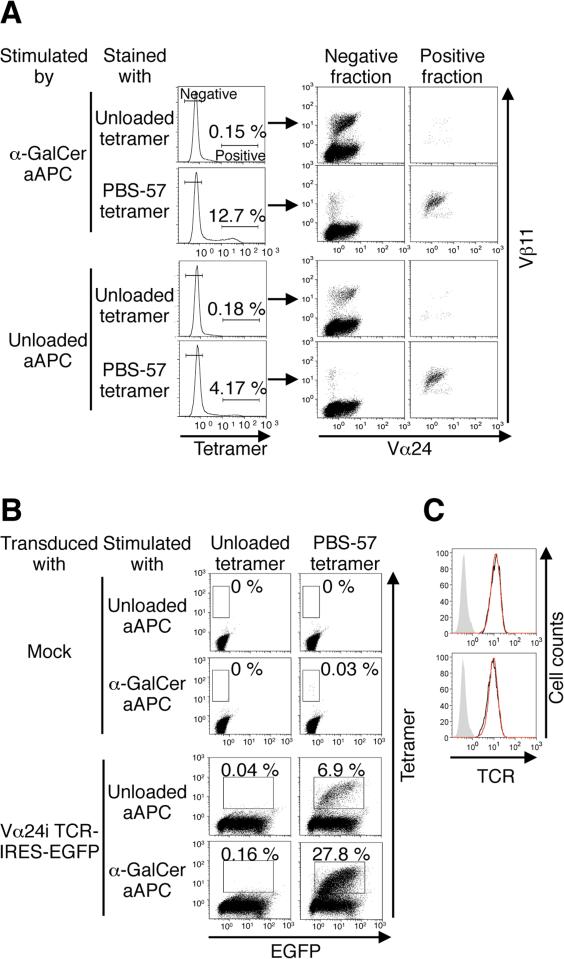

Figure 2. Vast majority of tetramer positive T cells expanded by aAPC stimulation were derived from Vα24i TCRα gene-transduced Vβ11+ T cells.

(A) The expanded T cells were costained with the indicated tetramers (5 μg/ml) and anti-Vα24/Vβ11 mAbs. The data are representative of 3 donors. (B) Peripheral CD3+ T cells were transduced with vector alone (mock) or with a Vα24i TCRα gene tagged with EGFP. Following stimulations with unloaded or α-GalCer-loaded aAPC, the transduced T cells were stained with CD1d tetramers. The data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (C) Peripheral T cells were transduced with the Vα24i TCRα gene and costained with anti-Vα24/TCR mAbs. The TCR expression levels were compared between the Vα24+ (red line) and Vα24- T cells (black line). The isotype control is shown in gray. Data for two different donors are shown.

3.2. A panel of iNKT TCRs with a broad range of autoreactivity were isolated and reconstituted

Although the Vα24i TCRα-transduced T cells, which proliferated in response to CD1d-restricted self-ligands, were detected by PBS-57 tetramer, they were not stained with the unloaded tetramer (Fig. 1E, Fig. 2A and B). This result suggests that the structural avidities of the functionally autoreactive Vα24i TCRα-transduced T cells were not sufficient for unloaded tetramer staining. Mallevaey et al. recently reported that the reconstitution of a T cell line with clonotypic mouse iNKT TCRs improved the apparent structural avidities of the cells, which could be positively stained with the unloaded tetramer [30]. Based on that finding, we studied whether the reconstitution of a human T cell line with clonotypic human iNKT TCRs could similarly enhance the cells’ structural avidities for unloaded tetramer. We cloned 54 unique Vβ11 TCRβ genes from the PBS-57 tetramer-positive fraction of Vα24i TCRα+ T cells that were stimulated with unloaded or α-GalCer-loaded aAPC as described in Fig. 1E. Along with the Vα24i TCRα gene, these genes were transduced into the human T cell line SupT1 to individually reconstitute the 54 iNKT TCRs. All 54 SupT1 transfectants were stained with graded concentrations of tetramers that were either unloaded or loaded with currently identified ligands (β-GlcCer, LPC, pLPE, or eLPA) as well as the PBS-57 tetramer. Although the PBS-57 tetramer positively stained all 54 transfectants similarly (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Fig. 1A), the self-ligand tetramers stained the transfectants to various degrees (Fig. 3A and C, and Supplementary Fig. 1B). None of the 54 transfectants were stained with eLPA-loaded human CD1d tetramer (data not shown). In addition to recognition of CD1d tetramers, functional responses of primary T cells expressing iNKT TCRs were also examined. All three independent iNKT TCR transfectants, representative of low (Cl.3041), intermediate (Cl. 3010), and high autoreactivity (Cl.1140), secreted IL-4 and/or IFN-γ when stimulated with CD1d-expressing aAPCs, which were enhanced in the presence of α-GalCer (Fig. 3B). To compare the structural avidities of these transfectants, EC50, the tetramer concentration that conferred 50% of the maximal staining level, was determined for the PBS-57 tetramer. However, the EC50 of the self-ligand tetramers could not be calculated for transfectants with low reactivities. Therefore, the structural avidities for the unloaded, β-GlcCer, LPC, and pLPE tetramers were defined as the % staining at concentrations of 5, 10, 10, and 5 μg/ml, respectively. Note that the EC50 and % tetramer positivity among the transfectants with calculable EC50 values correlated strongly (Fig. 3C). The structural avidities, as determined by the self-ligand tetramer staining data and CDR3β sequence information for the 54 transfectants, are shown in Table 1. Taken together, we have cloned and reconstituted a panel of human clonotypic iNKT TCRs with a broad range of self-reactivity as measured by self-ligand tetramer staining from a de novo repertoire.

3.3 Unloaded aAPC stimulation produces an iNKT TCR repertoire with higher autoreactivity

Since α-GalCer is a prototypic iNKT cell ligand and PBS-57 tetramer stains all iNKT cells regardless of their autoreactivity, α-GalCer-loaded aAPC should evenly expand Vα24i TCRα gene transduced T cells. In contrast, unloaded aAPC should selectively expand the transduced T cells with sufficient autoreactivity. To test this hypothesis, we compared the structural avidity for different self-ligand tetramers between the SupT1 transfectants expressing the iNKT TCRs isolated after stimulation with α-GalCer-loaded aAPC and the ones with unloaded aAPC. As we expected, the SupT1 transfectants expressing the iNKT TCRs isolated after stimulation with unloaded aAPC exhibited greater autoreactivity to all 4 tested self-ligand tetramers, compared with the transfectants expressing TCRs obtained via α-GalCer-loaded aAPC stimulation (Fig. 4A). By contrast, no difference in the structural avidity for PBS-57 tetramer was observed between the two populations (Fig. 4B). In order to examine whether the strength of autoreactivity is correlated with the avidity determined by PBS-57 tetramer, we calculated the correlations between the avidity for 4 self-ligand tetramers and PBS-57 tetramer. As shown in Fig. 4C, the structural avidity for any of the 4 self-ligand tetramers did not correlate with the avidity for the PBS-57 tetramer. These results are consistent with the previous finding that in iNKT TCR:CD1d:α-GalCer crystal structures, CDR3β contributes negligibly to the interaction [31, 32]. When iNKT TCRs recognize weak self-ligands, CDR3β is involved in the interaction between the TCR and CD1d/ligand complexes [30, 33, 34]. Our data suggest that the primary structure of CDR3β is a critical determinant for defining the autoreactive strength and that α-GalCer (i.e., PBS-57) tetramer staining does not provide relevant information regarding iNKT cell autoreactivity. Furthermore, our Vα24i TCRα gene transduction and aAPC stimulation system represents a novel strategy to selectively expand and isolate iNKT TCRs with strong autoreactivity.

3.4. Identification of three CDR3β amino acid sequence motifs associated with high autoreactivity

The CDR3β amino acid sequences of human primary iNKT cells have been reported to be highly heterogeneous and unique [2, 16, 29]. By scrutinizing the 54 CDR3β sequences shown in Table 1, we identified 3 CDR3β amino acid sequence motifs associated with high structural self-ligand avidity: a VD region with 2 or more acidic amino acids, usage of the Jβ2-5 allele, and a CDR3β region of 13 amino acids in length (Table 1). Both the univariate and multivariate analyses demonstrated that with one exception, the SupT1 transfectants positive for any of these three sequence motifs exhibited significantly higher structural avidity for any of the 4 tested self-ligands compared with the sequence motif-negative transfectants (Fig. 5). A non-significant trend was observed in which transfectants with the motif of a VD region with 2 or more acidic amino acids (≥2 D/E) possessed greater structural avidity for the LPC tetramer relative to motif-negative transfectants. Based on the number of sequence motifs encoded by the CDR3β region, the 54 SupT1 transfectants were classified into three cohorts of 0, 1, and 2 or 3 motifs. The iNKT TCRs encoding 2 or 3 motifs exhibited significantly higher autoreactivity than the iNKT TCRs with no more than 1 motif, irrespective of the self-ligand tetramers used to determine structural avidity (Fig. 6).

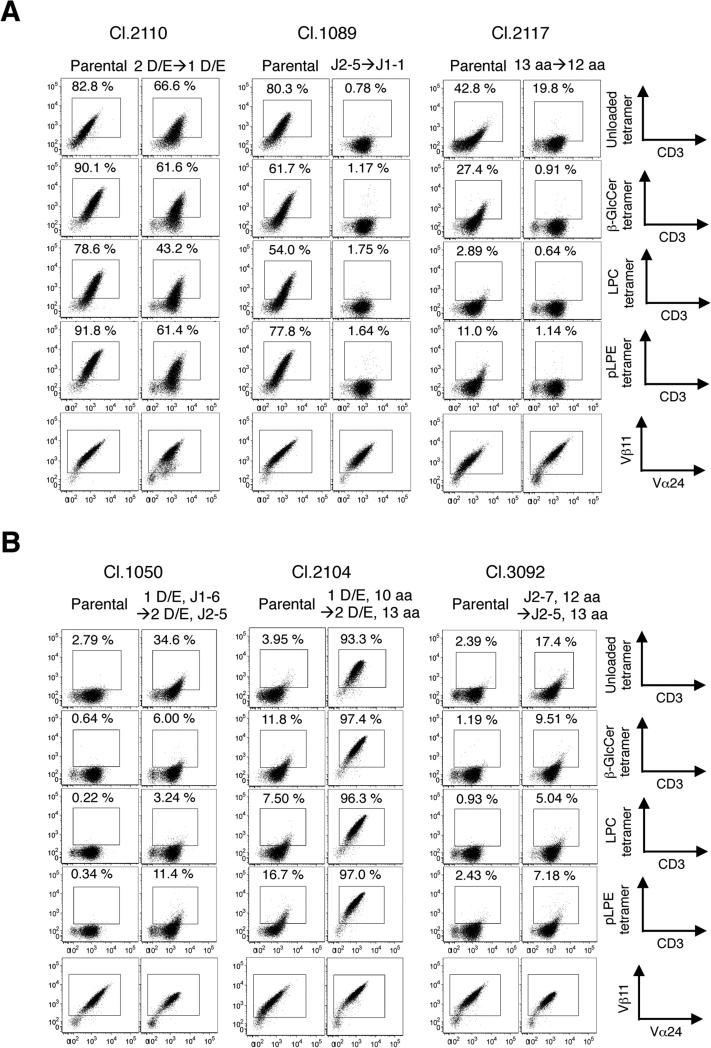

We next examined whether losses or gains of sequence motifs would reduce or improve the reactivities of the iNKT TCRs to self-ligand tetramers. As shown in Fig. 7A, the loss of one sequence motif reduced the reactivity to self-ligand tetramers despite comparable expression levels of parental and mutated TCRs. However, the gain of one sequence motif was not sufficient to increase the self-reactivity level (data not shown). A gain of two motifs did enhance the reactivity to self-ligand tetramers (Fig. 7B). These data indicate that the three identified CDR3β amino acid sequence motifs regulate and are associated with human iNKT TCR autoreactivity.

Figure 7. The effects of CDR3β sequence motif losses and gains on the structural avidity for self-ligands were studied using SupT1 transfectants.

SupT1 cells individually reconstituted with parental and mutated TCRβ chains were stained with the unloaded, β-GlcCer, LPC, and pLPE tetramer at the concentrations of 5, 5, 20, and 20 μg/ml. (A) One sequence motif each was abrogated, as indicated in Cl.2110 (left), Cl.1089 (center), and Cl.2117 (right). (B) Two indicated sequence motifs were added to Cl.1050 (left), Cl.2104 (center), and Cl.3092 (right). The CDR3β sequences of the generated mutants are described in the Materials and Methods.

4. Discussion

Human iNKT cell studies have been impeded partly by the availability of large numbers of cells and by the detectability of structurally autoreactive iNKT cells in the periphery. In this report, we overcame these issues by developing a novel method to generate a de novo iNKT TCR repertoire and isolated a large panel of iNKT TCRs with a wide range of autoreactivity. Primary T cells expressing the de novo iNKT TCRs were all positive for Vα24/Vβ11, and responded to CD1d-expressing aAPCs in a similar manner to conventional iNKT cells. We comprehensively investigated the autoreactive strength of this unprecedentedly large set of human iNKT TCRs and identified three CDR3β amino acid sequence motifs that were associated with strong autoreactivity: a VD region with 2 or more acidic amino acids, usage of the Jβ2-5 allele, and a CDR3β region of 13 amino acids in length. Our findings are underpinned by the previous reports that an acidic amino acid composition, J usage, and the CDR3β region amino acid length individually affected the affinities of conventional TCRs [35-37]. Importantly, human iNKT TCRs highly reactive for self-ligands reported to date indeed harbor 2 out of the 3 sequence motifs (Supplementary Table 1) [2, 10, 34, 38].

CDR3s are the critical regions in determining not only the affinity as described, but also specificity of TCRs. Although CDR3s of TCRs are diverse [2, 16, 29, 39], some reports suggest unique CDR3 amino acid sequence features are associated with specific reactivities of the TCRs [40-42]. Polyclonal CD8+ T cells specific for a SIV epitope were characterized by a highly conserved CDR3β amino acid sequence motif (CASSXXRXSNQPQY, where X is arbitrary). TCRs encoding this motif, however, lost recognition after single residue mutations in the cognate viral epitope, explaining the viral escape from T cell immunity [40]. It is reported that γδ TCRs specific for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class 1b molecule T22 largely encoded the prominent 4 CDR3γ sequence motifs: the existence of Trp in the V or D1 gene segment, Ser-Glu-Gly-Tyr-Glu in the D2 gene segment, Leu in the P nucleotide, and 13 CDR3 amino acid in length. Those sequence motifs regulated the specificity and affinity for T22 [41]. Another group demonstrated that Gly-Leu-Gly motif in CDR3β was one of the features of HLA-A2-restricted T cells specific for Melanoma antigen, Melan-A, and that this motif was found among different melanoma patients [42]. These evidences suggest that CDR3 sequence motifs are also associated with certain antigen-reactivities of non-iNKT TCRs.

Mallevaey et al. reported that a hydrophobic amino acid motif associated with higher mouse iNKT TCR autoreactivity, although the same sequence motif was not observed among the strongly autoreactive human iNKT TCRs in our study [30]. The identified CDR3β sequence motifs may allow us to predict the strength of CD1d-reactivity of human iNKT cells. Therefore, focused studies of iNKT cells in which the CDR3βs encode 2 or 3 motifs might facilitate exploration of the biological significance of iNKT cell autoreactivity during thymic selection and peripheral maintenance/activation. It should be noted that in addition to the 3 CDR3β sequence motif(s) described above, the existence of other motifs associated with strong iNKT TCR autoreactivity is highly likely. It is also possible that an unknown CDR3β sequence motif might be found to correlate with strong autoreactivity for only a certain self-ligand or a limited set of self-ligands.

By introducing the Vα24i gene into peripheral T cells, we obtained a large iNKT TCR repertoire with a wide range of autoreactivity. It was largely derived from conventional Vβ11+ T cells since transduction of the TCRα gene alone greatly increased the frequency of PBS-57 tetramer positive cells (Fig. 1D). These evidences also suggested that vast majority of conventional Vβ11+ T cells potentially serve as iNKT TCRs when paired with the Vα24i TCR. In other words, regardless of the CDR3β sequence diversity and the thymic selection restricted by CD1d, conventional Vβ11 TCRβ chains inherently possess the potential to recognize CD1d/α-GalCer complexes. This was also reflected in the comparable PBS-57 tetramer stain intensity across the 54 clones, which was not surprising given that CDR3β plays minimal roles in iNKT TCR/CD1d/α-GalCer crystal structures, as we mentioned above.

Crystallography studies demonstrated that iNKT TCRs recognize CD1d/ligand complexes in a parallel docking mode while conventional T cells recognize peptide/MHC complexes in a diagonal docking mode [31-34]. This particular docking mode enables CD1d-restricted lipid ligands to be molded by structurally conserved iNKT TCRs encoding germ-line sequences except for CDR3β sequences. In addition, unlike conventional TCRs, iNKT TCR CDR3βs only interact directly with the CD1d molecule. This lock-and-key interaction regardless of different ligands explains the inherent autoreactivity of iNKT TCRs [16, 17, 31]. Since the three CDR3β motifs we identified dictate strong autoreactivity of human iNKT TCRs, these motifs may regulate the iNKT TCR structure so that the strength of interaction with CD1d is enhanced directly or indirectly. The fact that two crystal structures of human iNKT TCRs encoding two of the three motifs did not highlight a major role for these motifs in interactions with CD1d may support the latter [10, 34]. Nevertheless, further structure analysis would be necessary to pinpoint the roles of the three motifs on the amino acid level in determining the high TCR autoreactivity.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we developed a new strategy to generate a de novo iNKT TCR repertoire and isolate a large panel of iNKT TCRs with a broad range of autoreactivity. Intensive analysis of the de novo iNKT TCRs would provide more insights on the nature of iNKT cell autoreactivity, as mediated by the three identified CDR3β amino acid motifs. This finding further our understanding of self-recognition by iNKT cells, which are involved in immune responses associated with diverse diseases.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Introducing Vα24i gene to peripheral T cells generates a novel iNKT TCR repertoire.

Stimulation by unloaded aAPCs enriches strongly autoreactive iNKT TCR transfectants.

A large panel of human iNKT TCRs with a broad range autoreactivity are isolated.

Three CDR3β sequence motifs associated with high autoreactivity are identified.

Human iNKT TCRs encoding 2 or 3 sequence motifs exhibit higher autoreactivity.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the NIH Tetramer Core Facility for the provision of human CD1d tetramers. We gratefully acknowledge Thierry Mallevaey for providing helpful discussions.

Finding

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 CA148673 (NH); the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research Clinical Investigator Award IA-039 (NH); The Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation (MOB, NH); Knudson Postdoctoral Fellowship (KC); Canadian Institutes of Health Research Canada Graduate Scholarship (TG); and Guglietti Fellowship Award (TO).

Abbreviations

- aAPC

artificial antigen-presenting cells

- α-GalCer

α-galactosylceramide

- β-GlcCer

β-glucopyranosylceramide

- CDR

complementarity-determining region

- eLPA

C16-alkanyl-lysophosphatidic acid

- iNKT

invariant natural killer T

- LPC

Lyso-phosphatidylcholine

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- pLPE

C16-lysophosphatidylethanolamine

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematous

- TCR

T cell receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authorship

K.C., O.I., and N.H. designed the project. K.C., T.G., O.I., M.T., M.N., T.O., and Y.Y. performed the experimental work. A.M.S. and T.I.S. performed the statistical analyses. M.O.B. provided the human samples. K.C. and T.G. analyzed the results and contributed to writing the manuscript. M.O.B contributed to writing the manuscript. N.H. wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Salio M, Silk JD, Jones EY, Cerundolo V. Biology of CD1- and MR1-restricted T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:323–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossjohn J, Pellicci DG, Patel O, Gapin L, Godfrey DI. Recognition of CD1d-restricted antigens by natural killer T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:845–57. doi: 10.1038/nri3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brennan PJ, Brigl M, Brenner MB. Invariant natural killer T cells: an innate activation scheme linked to diverse effector functions. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:101–17. doi: 10.1038/nri3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf MJ, Adili A, Piotrowitz K, Abdullah Z, Boege Y, Stemmer K, et al. Metabolic activation of intrahepatic CD8+ T cells and NKT cells causes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and liver cancer via cross-talk with hepatocytes. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:549–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porcelli S, Yockey CE, Brenner MB, Balk SP. Analysis of T cell antigen receptor (TCR) expression by human peripheral blood CD4-8- alpha/beta T cells demonstrates preferential use of several V beta genes and an invariant TCR alpha chain. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dellabona P, Padovan E, Casorati G, Brockhaus M, Lanzavecchia A. An invariant V alpha 24-J alpha Q/V beta 11 T cell receptor is expressed in all individuals by clonally expanded CD4-8- T cells. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1171–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gadola SD, Dulphy N, Salio M, Cerundolo V. Valpha24-JalphaQ-independent, CD1d-restricted recognition of alpha-galactosylceramide by human CD4(+) and CD8alphabeta(+) T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2002;168:5514–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Motoki K, et al. CD1d-Restricted and TCR-Mediated Activation of V14 NKT Cells by Glycosylceramides. Science. 1997;278:1626–9. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brennan PJ, Tatituri RV, Brigl M, Kim EY, Tuli A, Sanderson JP, et al. Invariant natural killer T cells recognize lipid self antigen induced by microbial danger signals. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1202–11. doi: 10.1038/ni.2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez-Sagaseta J, Sibener LV, Kung JE, Gumperz J, Adams EJ. Lysophospholipid presentation by CD1d and recognition by a human Natural Killer T-cell receptor. EMBO J. 2012;31:2047–59. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Facciotti F, Ramanjaneyulu GS, Lepore M, Sansano S, Cavallari M, Kistowska M, et al. Peroxisome-derived lipids are self antigens that stimulate invariant natural killer T cells in the thymus. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:474–80. doi: 10.1038/ni.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girardi E, Zajonc DM. Molecular basis of lipid antigen presentation by CD1d and recognition by natural killer T cells. Immunol Rev. 2012;250:167–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kain L, Webb B, Anderson BL, Deng S, Holt M, Costanzo A, et al. The identification of the endogenous ligands of natural killer T cells reveals the presence of mammalian alpha-linked glycosylceramides. Immunity. 2014;41:543–54. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brennan PJ, Tatituri RV, Heiss C, Watts GF, Hsu FF, Veerapen N, et al. Activation of iNKT cells by a distinct constituent of the endogenous glucosylceramide fraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:13433–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415357111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bendelac A, Lantz O, Quimby ME, Yewdell JW, Bennink JR, Brutkiewicz RR. CD1 recognition by mouse NK1+ T lymphocytes. Science. 1995;268:863–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7538697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gapin L. iNKT cell autoreactivity: what is 'self' and how is it recognized? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:272–7. doi: 10.1038/nri2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gapin L, Godfrey DI, Rossjohn J. Natural Killer T cell obsession with self-antigens. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25:168–73. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vahl JC, Heger K, Knies N, Hein MY, Boon L, Yagita H, et al. NKT cell-TCR expression activates conventional T cells in vivo, but is largely dispensable for mature NKT cell biology. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Bishop KA, Hegde S, Rodenkirch LA, Pike JW, Gumperz JE. Human invariant natural killer T cells acquire transient innate responsiveness via histone H4 acetylation induced by weak TCR stimulation. J Exp Med. 2012;209:987–1000. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brigl M, Bry L, Kent SC, Gumperz JE, Brenner MB. Mechanism of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cell activation during microbial infection. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1230–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bosma A, Abdel-Gadir A, Isenberg DA, Jury EC, Mauri C. Lipid-antigen presentation by CD1d(+) B cells is essential for the maintenance of invariant natural killer T cells. Immunity. 2012;36:477–90. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bedel R, Berry R, Mallevaey T, Matsuda JL, Zhang J, Godfrey DI, et al. Effective functional maturation of invariant natural killer T cells is constrained by negative selection and T-cell antigen receptor affinity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E119–28. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320777110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butler MO, Friedlander P, Milstein MI, Mooney MM, Metzler G, Murray AP, et al. Establishment of antitumor memory in humans using in vitro-educated CD8+ T cells. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:80ra34. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butler MO, Hirano N. Human cell-based artificial antigen-presenting cells for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. 2014;257:191–209. doi: 10.1111/imr.12129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ochi T, Nakatsugawa M, Chamoto K, Tanaka S, Yamashita Y, Guo T, et al. Optimization of T-cell reactivity by exploiting TCR chain centricity for the purpose of safe and effective antitumor TCR gene therapy. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015 doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakatsugawa M, Yamashita Y, Ochi T, Tanaka S, Chamoto K, Guo T, et al. Specific Roles of Each TCR Hemichain in Generating Functional Chain-Centric TCR. J Immunol. 2015;194:3487–500. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gapin L, Matsuda JL, Surh CD, Kronenberg M. NKT cells derive from double-positive thymocytes that are positively selected by CD1d. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:971–8. doi: 10.1038/ni710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Godfrey DI, Berzins SP. Control points in NKT-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:505–18. doi: 10.1038/nri2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mallevaey T, Clarke AJ, Scott-Browne JP, Young MH, Roisman LC, Pellicci DG, et al. A molecular basis for NKT cell recognition of CD1d-self-antigen. Immunity. 2011;34:315–26. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borg NA, Wun KS, Kjer-Nielsen L, Wilce MC, Pellicci DG, Koh R, et al. CD1d-lipid-antigen recognition by the semi-invariant NKT T-cell receptor. Nature. 2007;448:44–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pellicci DG, Patel O, Kjer-Nielsen L, Pang SS, Sullivan LC, Kyparissoudis K, et al. Differential recognition of CD1d-alpha-galactosyl ceramide by the V beta 8.2 and V beta 7 semi-invariant NKT T cell receptors. Immunity. 2009;31:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scott-Browne JP, Matsuda JL, Mallevaey T, White J, Borg NA, McCluskey J, et al. Germline-encoded recognition of diverse glycolipids by natural killer T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1105–13. doi: 10.1038/ni1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pellicci DG, Clarke AJ, Patel O, Mallevaey T, Beddoe T, Nours J, et al. Recognition of beta-linked self glycolipids mediated by natural killer T cell antigen receptors. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:827–33. doi: 10.1038/ni.2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Udyavar A, Alli R, Nguyen P, Baker L, Geiger TL. Subtle affinity-enhancing mutations in a myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-specific TCR alter specificity and generate new self-reactivity. J Immunol. 2009;182:4439–47. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yokosuka T, Takase K, Suzuki M, Nakagawa Y, Taki S, Takahashi H, et al. Predominant role of T cell receptor (TCR)-alpha chain in forming preimmune TCR repertoire revealed by clonal TCR reconstitution system. J Exp Med. 2002;195:991–1001. doi: 10.1084/jem.20010809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reynolds C, Chong D, Raynsford E, Quigley K, Kelly D, Llewellyn-Hughes J, et al. Elongated TCR alpha chain CDR3 favors an altered CD4 cytokine profile. BMC Biol. 2014;12:32. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-12-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matulis G, Sanderson JP, Lissin NM, Asparuhova MB, Bommineni GR, Schümperli D, et al. Innate-like control of human iNKT cell autoreactivity via the hypervariable CDR3beta loop. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arstila TP, Casrouge A, Baron V, Even J, Kanellopoulos J, Kourilsky P. A direct estimate of the human alphabeta T cell receptor diversity. Science. 1999;286:958–61. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Price DA, West SM, Betts MR, Ruff LE, Brenchley JM, Ambrozak DR, et al. T cell receptor recognition motifs govern immune escape patterns in acute SIV infection. Immunity. 2004;21:793–803. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shin S, El-Diwany R, Schaffert S, Adams EJ, Garcia KC, Pereira P, et al. Antigen recognition determinants of gammadelta T cell receptors. Science. 2005;308:252–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1106480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Serana F, Sottini A, Caimi L, Palermo B, Natali PG, Nistico P, et al. Identification of a public CDR3 motif and a biased utilization of T-cell receptor V beta and J beta chains in HLAA2/Melan-A-specific T-cell clonotypes of melanoma patients. J Transl Med. 2009;7:21. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.