Abstract

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) is a high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasm first described in the lung and subsequently well documented in many other anatomic sites. It has only recently been recognized that LCNEC can also rarely arise in the head and neck. The role of human papillomavirus (HPV), which is associated with some small cell carcinomas of the head and neck, has not been investigated for LCNEC. We sought to further characterize the histologic, immunophenotypic, and clinical features of LCNEC and also investigate the role of HPV in this newly described group of tumors.

The surgical pathology archives of two large academic institutions were searched for cases of LCNEC arising in the head and neck. P16 immunohistochemistry and HPV in situ hybridization were performed, and clinical information was obtained by electronic medical records.

Ten cases of head and neck LCNEC were identified. The tumors arose in 6 men and 4 women ranging in age from 14 to 70 years (median, 63.5 years). The primary tumor sites were oropharynx (n=4), sinonasal tract (n=3), and larynx (n=3). The LCNECs consisted of nests and trabeculae of medium-large cells with abundant cytoplasm, coarse chromatin and prominent nucleoli with very high mitotic rates. The tumor nests were often associated with necrosis, peripheral palisading, and rosette formations. The LCNECs were positive for pan-cytokeratin and at least one neuroendocrine marker (most often synaptophysin) and were largely negative for p63 (focal staining in 2 of 10) and CK5/6 (staining in 1 of 10). The LCNECs demonstrated aggressive clinical behavior: 8 of 10 presented with advanced disease, 5 of 10 died, with 4 more living but with persistent tumor. Three of 10 LCNECs were HPV related (HPV-LCNEC); they arose in the oropharynx (n=2) and sinonasal tract (n=1). The HPV-LCNECs did not differ from the HPV-negative tumors in histologic appearance or behavior: 2 patients with HPV-LCNEC have died due to their disease and 1 remains alive but with widespread metastases.

LCNEC is a rare but distinct form of head and neck carcinoma that exhibits aggressive clinical behavior. A subset of oropharyngeal and sinonasal LCNEC is HPV-related, but the presence of HPV may not impart a more favorable prognosis. Due to its aggressive behavior, LCNEC should be distinguished from moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. The morphology of LCNEC overlaps considerably with the non-keratinizing appearance of HPV-related squamous cell carcinoma, and as a result, a high index of suspicion is needed to identify LCNEC. Immunohistochemistry for synaptophysin and p63 are helpful tools for making this distinction.

Keywords: large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, small cell carcinoma, moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma, atypical carcinoid tumor, human papillomavirus, HPV

Introduction

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) is a rare, high-grade epithelial neuroendocrine malignancy first described in the lung and subsequently well documented in many other anatomic sites.(1-3) Histologically, LCNEC is characterized by a) large, polygonal cells with coarse nuclear chromatin and prominent nucleoli, b) high mitotic rate and frequent necrosis, c) architectural patterns suggestive of neuroendocrine differentiation (organoid nests, trabeculae, rosettes, and/or peripheral palisading) and d) immunohistochemical evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation (i.e., immunostaining with synaptophysin, chromogranin, and/or CD56).(1-3)

In the most recently published 2005 edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumors, LCNEC was not included as an entity.(4) Instead, the head and neck tumors meeting histologic criteria for LCNEC were previously regarded simply as high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas, not otherwise specified or as belonging within the spectrum of moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (so-called “atypical carcinoid tumor”).(5, 6) In recent years, however, there has been increasing recognition that LCNEC – defined by the established lung criteria – indeed represents a distinct tumor entity in the head and neck.(6-8) Although fewer than 40 head and neck cases have been reported, LCNEC appears to occur most commonly in the larynx and appears to be a highly aggressive carcinoma similar to small cell carcinoma and LCNEC of the lung and other sites.(8-21)

Human papillomavirus (HPV) has been shown to be associated with an increasingly large subset of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, with HPV-related carcinomas accounting for up to 80% of carcinomas of the oropharynx (22-24) and 20-25% of those arising in the sinonasal tract.(25-27) In the oropharynx, the presence of HPV is a powerful prognostic indicator. Patients with HPV-related carcinomas consistently experience a lower risk of tumor progression and tumor-related death than patients with HPV-negative carcinomas.(28-30) Accordingly, HPV positivity is used to stratify patients for less intensive therapy in several clinical trials.(31) The purpose of this study was to provide a comprehensive description of the histologic, immunophenotypic, and clinical features of 10 previously unpublished cases of head and neck LCNEC; and to determine the presence and clinical significance of HPV in these tumors.

Materials and Methods

Cases

After obtaining IRB approval, cases of LCNEC arising in the head and neck were identified from a computerized search of the surgical pathology files of The Johns Hopkins Hospital and University of Virginia Medical Center between 1995 and 2014. For each case, all surgical pathology slides were reviewed to confirm the diagnosis. Similar to prior studies, the well-established criteria for lung LCNEC were applied: a) large, polygonal cells with coarse nuclear chromatin and prominent nucleoli, b) mitotic rate ≥10 per 10 high-power fields and frequent necrosis, c) architectural patterns suggestive of neuroendocrine differentiation (organoid nests, trabeculae, rosettes, and/or peripheral palisading) and d) immunohistochemical evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation (i.e., immunostaining with synaptophysin, chromogranin, and/or CD56).(1, 2, 32) A representative block was chosen for in situ hybridization and immunohistochemical studies. Medical records were reviewed to document patient age, sex, smoking history, primary site of tumor origin, treatment and patient outcome. Additional death information was obtained from the publicly available United States Social Security Administration Death Index.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical studies were performed on 5 μm-thick sections prepared from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue using standard autostaining protocols on a Ventana Benchmark XT autostainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc, Tucson, AZ). Deparaffinization and antigen retrieval (i-view detection system; Ventana) were carried out as an automated program of the Ventana autostainer. The primary antibodies and final dilutions were: thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) (clone 8G7G3/1; Ventana, Tucson, AZ; prediluted by manufacturer); p63 (clone 4A4; BioCare, Concord, CA; prediluted by manufacturer); AE1/AE3 (pck-26; Ventana, Tucson, AZ; prediluted by manufacturer); synaptophysin (clone 27G12; Novacastra; 1:400); chromogranin (clone LK2H10; Ventana, Tucson, AZ; prediluted by manufacturer); CK5/6 (clone D5/16 B4; Ventana, Tucson, AZ; prediluted by manufacturer); CD56 (clone 123C3.D5; Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA, prediluted by manufacturer). In positive cases, TTF-1 and p63 demonstrated nuclear reactivity, while synaptophysin, chromogranin, AE1/AE3 and CK5/6 showed cytoplasmic staining. “Focal” immunoreactivity was defined as ≤ 5% of cells.

Human Papillomavirus Testing

All cases were screened for high-risk HPV by immunohistochemistry for p16 (clone INK4a; Ventana, Tucson, AZ; prediluted by manufacturer). Nuclear and cytoplasmic staining in at least 70% of tumor cells was considered positive.(23) For cases that were p16-positive, in situ hybridization for high-risk HPV DNA was performed. Sections of 5 μm from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were evaluated for the presence of HPV DNA with an automated protocol utilizing the Ventana HR HPV III probe set that captures HPV genotypes 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, and 66 (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ). Finally, in cases where p16 immunochemistry was positive but in-situ hybridization for high-risk HPV DNA was negative, a second methodology for detection of viral nuclei acids was utilized for confirmation of HPV status. Sections of 5 μm from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were evaluated for the presence of HPV RNA using a manual RNAscope HPV-HR18 Probe (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Hayward, CA) which recognizes 18 high-risk HPV genotypes (16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, and 82). HPV positive controls included HPV 16-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma as well as the HPV 16-positive SiHa and CaSki cell lines. An HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma served as a negative control.

Results

Ten cases of head and neck LCNEC were identified. The clinical features of these LCNEC are summarized in Table 1. Patients ranged in age from 14-70 years (mean 57 years; median, 63.5 years), with four females and 6 males. The LCNECs arose in the sinonasal tract (n=4), oropharynx (n=3), and larynx (n=3). In the 8 patients with documented smoking histories, 7 were smokers. Most of the patients presented with advanced clinical disease: two of the oropharyngeal LCNECs presented with distant metastatic disease, 3 of the laryngeal and 1 sinonasal LCNEC presented with neck lymph node metastases, and 2 sinonasal tumors presented with intracranial invasion. Only 2 of 10 LNCECs – a nasal tumor and an oropharyngeal tumor – presented with the tumor clinically confined to the site of tumor origin.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of patients with HPV-related large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas of the head & neck

| Case # | HPV Status |

Site | Histology | Age | Sex | Smoking | Presentation | Treatment | Clinical Course |

Outcome | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | + | tonsil | LCNEC/SmCC | 65 | M | + | oropharyngeal mass + widely disseminated metastases |

hospice | distant metastases |

AWD | 9 |

| 2 | + | tonsil | LCNEC | 57 | M | + | oropharyngeal mass + widely disseminated metastases |

palliative CT | distant metastases |

DWD | 2 |

| 3 | + | sinonasal | LCNEC | 58 | M | + | sinonasal mass with intracranial extension/bony erosion |

surgery/CT/RT | progressive disease |

DWD | 12 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 4 | − | sinonasal | LCNEC/SmCC | 68 | M | + | large sinonasal mass + neck metastasis |

CT/RT | distant metastases |

DWD | 18 |

| 5 | − | epiglottis | LCNEC/SqCC | 62 | M | + | epiglottic mass + neck metastasis | surgery/CT/RT | complete response |

NED | 34 |

| 6 | − | supraglottis | LCNEC/SqCC | 65 | F | + | supraglottic lesion + lymphadenopathy |

surgery/CT/RT | distant metastases |

DWD | 13 |

| 7 | − | tonsil | LCNEC/dysplasia | 65 | M | unknown | oropharyngeal mass | unknown | unknown | Died, cause unknown |

12 |

| 8 | − | sinonasal | LCNEC | 70 | F | unknown | sinonasal mass with intracranial extension/bony erosion |

surgery/CT/RT | distant metastases |

AWD | 9 |

| 9 | − | larynx | LCNEC | 46 | F | + | supraglottic lesion + lymphadenopathy |

surgery/CT/RT | distant metastases |

AWD | 16 |

| 10 | − | nasal cavity | LCNEC | 14 | F | − | nasal mass | not yet initiated | new diagnosis |

AWD | 1 |

Abbreviations: HPV = human papillomavirus; LCNEC = large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma; SmCC = small cell carcinoma; SqCC = squamous cell carcinoma; LN = lymph node; CT = chemotherapy; RT = radiation therapy; DWD = dead with disease; AWD = alive with disease; NED = no evidence of disease

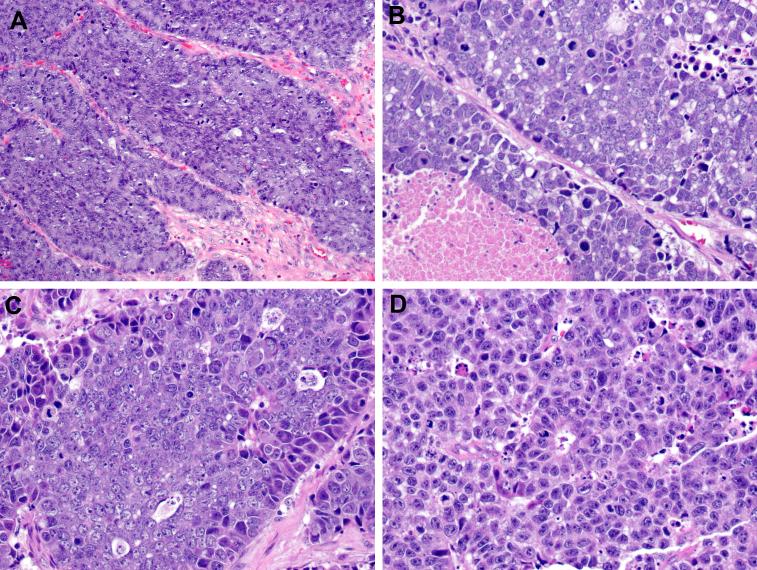

Morphologically, the LCNEC in our series conformed to the histologic definition of this entity in the lung and other sites: nests and trabeculae of medium to large polygonal cells with abundant cytoplasm, coarse to vesicular chromatin, and prominent nucleoli, high mitotic activity, frequent areas of geographic necrosis, and nuclear palisading around the periphery of nests, vessels (i.e., pseudo-rosettes), or gland-like rosette structures, (Figure 1). Mitotic rates ranged from 16 to 102 mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields (mean, 45). Three cases exhibited squamous differentiation: two laryngeal cases had minor components of invasive squamous cell carcinoma scattered among the LCNEC, and one oropharyngeal case had squamous cell carcinoma-in-situ of the epithelium overlying the LCNEC. In addition, there were 2 combined LCNEC-small cell carcinomas: one arising in the sinonasal tract and one arising in the oropharynx.

Figure 1.

The HPV- LCNECs grew as nests and trabeculae of basophilic tumor cells (A). All cases exhibited high-grade cellular features, including high-mitotic rates and necrosis (B). The HPV- LCNECs demonstrated peripheral palisading of tumor nuclei and nuclei with coarse chromatin and prominent nucleoli (C). One histologic clue to the diagnosis of LCNEC was the presence of scattered gland-like rosette structures (center) (D).

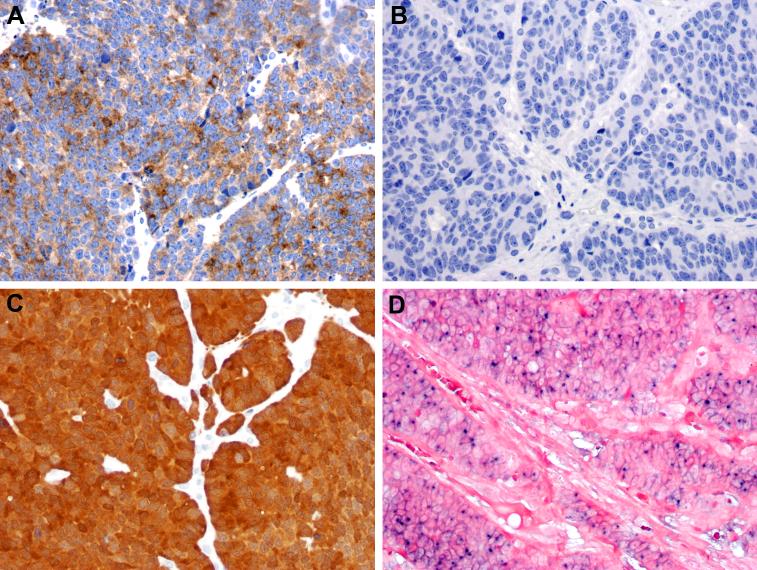

The immunohistochemical features of the LCNECs are summarized in Table 2. All LCNEC cases were diffusely positive for pan-cytokeratin, and all were positive for at least one neuroendocrine marker: 9 of 10 with synaptophysin, 5 of 8 with CD56, and 3 of 10 with chromogranin. TTF-1 was negative in all 10 LCNECs. The diffuse immunoexpression of p63 that characterizes squamous cell carcinoma was seen only within the squamous areas in the 3 LCNECs with a squamous cell carcinoma component; focal staining was present in the LCNEC of 2 other cases. Similarly, the squamous marker CK5/6 was positive in the squamous carcinoma components of the mixed LCNEC/squamous cell carcinomas, and unexpectedly in 1 sinonasal LCNEC that was p63-negative.

Table 2.

In-situ hybridization and immunohistochemical findings in HPV-related large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas of the head and neck

| Case # | CK | p63 | CK5/6 | synaptophysin | chromogranin | TTF-1 | CD56 | p16 | HPV ISH* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | + |

| 2 | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| 3 | + | − | + | + | + | − | ND | + | + |

| 4 | + | − | − | focal + | − | − | + | − | ND |

| 5 | + | +(in SqCC) | + (in SqCC) | + | + | − | focal + | − | ND |

| 6 | + | + (in SqCC) | +(in SqCC) | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| 7 | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − |

| 8 | + | focal + | ND | + | − | − | + | − | ND |

| 9 | + | focal + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 10 | + | − | ND | + | + | − | ND | + | − |

Abbreviations: HPV = human papillomavirus; CK = cytokeratin; SqCC = squamous cell carcinoma; TTF-1 = thyroid transcription factor-1; ISH = in situ-hybridization; ND = not done; focal = immunostaining in ≤5% of cells.

HPV testing revealed that while 6 of 10 LCNECs were p16-positive by immunohistochemistry, only 3 of 10 were positive for high-risk HPV by in situ hybridization, and could therefore be regarded as HPV-related LCNEC (HPV-LCNEC). In cases where p16 and HPV DNA in situ hybridization were discordant, HPV RNA in situ hybridization was utilized to confirm the absence of transcriptionally-active HPV. The HPV-LCNECs arose in the oropharynx (n=2) and sinonasal tract (n=1) of men, age 57, 58, and 65. All three men were smokers.

Most of the LCNECs (6 of 10) were treated with some combination of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy. For one patient, treatment information was unavailable. Another patient was newly diagnosed and has yet to undergo therapy. Finally, one patient went directly to hospice care without treatment at the time of diagnosis. The outcomes of the LCNECs were poor. Six of ten patients developed distant metastases, and five patients died, 2-18 months following diagnosis. Four of the deaths were the result of their LCNEC; one death (patient 7) was determined by the publicly available United States Social Security Administration Death Index, but the cause could not be determined. Distant metastases occurred in the lung (n=4) and brain (n=1); the precise sites of distant metastasis were not known in 2 cases. One patient remains alive with disease in hospice care 9 months after diagnosis. Two patients that developed distant metastases were still living with disease 9-16 months after diagnosis (mean, 12.5 months) and only one patient showed a complete response to therapy and has no evidence of disease 34 months after diagnosis.

As demonstrated in Table 1, the oropharyngeal HPV-LCNECs presented with widely disseminated metastases and the sinonasal HPV-LCNEC presented with intracranial extension. On follow-up, two patients died of their disease 2-12 months after diagnosis (mean, 7 months) and 1 patient was alive in hospice care 9 months after diagnosis. Two of the HPV-LCNECs were purely LCNEC, and 1 was mixed with a minor small cell carcinoma component; none of the HPV-LCNEC had a squamous component. As demonstrated in Table 2, the histologic and immunophenotypic findings of the HPV-LCNECs were essentially identical to those that were HPV-negative.

Discussion

In the previous edition of the World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumors, LCNEC – a well-established tumor type in the lung and many other organs – was not included as a diagnostic category; instead, it was noted that some moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas “may fulfill the diagnostic criteria of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung”.(5) Despite this, in recent years LCNEC of the head and neck has been recognized as a distinct entity. Thirty-eight cases have been reported to date, in patients ranging from 9 to 88 years (mean, 61 years).(8-21) There is a strong male predilection, with 32 of 38 cases (84%) arising in men. The affected sites have been larynx (n=22), parotid gland (n=6), oropharynx (n=3), nasopharynx (n=3), sinonasal tract (n=3), and hypopharynx (n=1). Most patients have been smokers.

This series of LCEC represents the largest series reported to date for the head and neck region. The findings are largely in agreement with those previously reported, though our series had a more even anatomic distribution (4 sinonasal, 3 oropharyx, 3 larynx) than most previous reports where laryngeal cases dominated. Most important, the clinical courses of the 10 patients from this series support that LCNEC of the head and neck is a very aggressive neoplasm. Indeed, growing experience with head and neck LCNEC indicates its behavior and prognosis is much more similar to small cell carcinoma than moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma. For example, in a meta-analysis, van der Laan, et al. found that most patients with laryngeal LCNEC presented with advanced disease, and that the 5-year disease free survival was 15%.(14) By comparison, the 5-year survivals of laryngeal small cell carcinoma and moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma were 19% and 53%, respectively.(14) The findings of this study further underscore the need to separate LCNEC from moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma in the upcoming edition of the WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumors.

A subset of small cell carcinomas arising the oropharynx and sinonasal tract harbors high-risk HPV.(27, 33, 34) Moreover, while HPV status in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma typically drives prognosis, HPV status does not appear to be protective in small cell carcinomas of the oropharynx, which often present at advanced stage and behave in an aggressive fashion regardless of viral positivity.(33, 34) Similarly, this study found that 3 of 10 LCENCs were HPV-related (HPV-LCNEC), and they were restricted to the oropharynx and sinonasal tract. This is not surprising given that the oropharynx and sinonasal tract are the two anatomic “hot spots” for HPV-related head and neck carcinomas.(25, 27, 34) Outside of these 2 anatomic subsites, HPV-related head and neck squamous cell carcinomas are very rare, and this trend appears to apply to HPV-related neuroendocrine carcinomas as well. While Halmos, et al. did detect HPV in two p16-negative laryngeal tumors (one LCNEC and one moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma) using a polymerase chain reaction-based approach,(15) this study is the first to detect integrated high-risk HPV in the nuclei of p16-positive LCNECs, findings highly suggestive of virally-driven neoplasia.

HPV-LCNEC has been previously reported in the uterine cervix, where it is associated with extremely aggressive clinical behavior and resistance to therapy.(35-37) HPV-LCNEC of the head and neck may share aggressive behavior with their cervical counterpart. In our series, in limited numbers (n=3) HPV-LCNEC presented with either widely disseminated or locally advanced disease and then took an aggressive clinical course, with two patients dying of disease within an average of 7 months post-diagnosis and a third patient entering directly into hospice care. This behavior of HPV-LCNEC represents a sharp departure from that typically expected of HPV-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, where HPV positivity is associated with an expectation of a relatively good prognosis and potential for long-term survival.(28, 29)

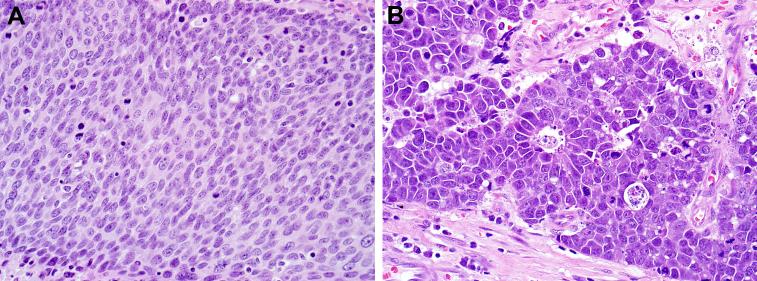

Given the poor prognosis, proper identification of cases of head and neck LCNEC is critical. LCNEC is simply separated from moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma on the basis of mitotic rates: moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma has 2-10 mitoses per 10 high-power fields while LCNEC has more than 10 (often many more).(6-8) The distinction between LCNEC and conventional keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma is not usually difficult, but the morphologic features of HPV-LCNEC overlap significantly with the non-keratinizing appearance of many HPV-related squamous cell carcinomas. Both tumors display a basophilic appearance at low power with a high nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio, high mitotic rates, and may exhibit peripheral nuclear palisading, and large areas of central necrosis. As squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx are often routinely tested for the presence of HPV, a positive result could be misleading regarding tumor behavior and prognosis if the features of LCNEC morphology are not recognized. HPV-related tumors in this location should be carefully evaluated for morphologic evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation, which admittedly is often subtle. Histologic clues include a prominent ribbon-like or trabecular architecture, a coarse chromatin quality, better-defined cell borders, prominent nuclear palisading at the periphery of nests or, most helpful, around vessels (pseudo-rosettes) or gland-like rosette structures.(see Figure 3 for a side-to-side morphologic comparison) If there is even a slight suspicion of an LCNEC tumor component, adjunctive immunohistochemistry should be employed. HPV-related squamous cell carcinoma should be diffusely positive for p63 and CK5/6 and negative for neuroendocrine markers. In contrast, LCNEC is negative for focal for p63, almost always negative for CK5/6, and positive for at least one neuroendocrine marker, usually synaptophysin.

Figure 3.

In contrast to HPV-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma which demonstrates oval nuclei with finely dispersed chromatin, sheet-like growth with indistinct cell borders, and an absence of rosettes (A), LCNEC is often more trabecular in its growth, with well-defined cell borders, coarse chromatin, and scattered gland-like rosettes (B).

Additionally, it must be emphasized that p16 alone is not a suitable surrogate for HPV testing when dealing with LCNEC of the head and neck. Indeed, we encountered 3 cases of HPV-negative LCNEC that demonstrated diffuse p16 positivity, a situation similar to small cell carcinoma of the head and neck which is also frequently p16-positive regardless of HPV status.(34) Indeed, high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas (both LCNEC and small cell carcinoma) in the lung and other sites very frequently express p16 diffusely via mechanisms independent of viral infection (i.e. inactivation of retinoblastoma protein (RB).(38-41) This again emphasizes the importance of first recognizing the morphologic features of LCNEC prior interpreting either p16 positivity or HPV status as indicative of improved clinical prognosis.

In summary, we present 10 previously unreported cases of head and neck LCNEC, including 3 HPV-related cases. Similar to HPV-related small cell carcinoma, the HPV status of these LCNEC does not appear to be protective. Given the morphologic similarity with HPV-related squamous cell carcinoma, a high index of suspicion is necessary to properly identify these cases and guide prognosis and therapy accordingly.

Figure 2.

All of the HPV- LCNECs were positive for the neuroendocrine marker synaptophysin (A) and negative for the squamous marker p63 (B). All of the HPV-related (and 3 of the HPV-negative) LCNECs were positive for p16 by immunohistochemistry (C). The HPV-related LCNECs were defined by the presence of nuclei signals by DNA in situ hybridization for high-risk HPV (D).

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIH/NIDCR) Head and Neck SPORE Grant P50 DE019032.

References

- 1.Travis WD, Linnoila RI, Tsokos MG, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung with proposed criteria for large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. An ultrastructural, immunohistochemical, and flow cytometric study of 35 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:529–553. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199106000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang SX, Kameya T, Shoji M, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung: a histologic and immunohistochemical study of 22 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:526–537. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199805000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brambilla E, Beasley MB, Chirieac LR, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. In: Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, et al., editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus, and Heart. IARC Pess; Lyon, France: 2015. pp. 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes L, Eveson JW, Relchart P, et al. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes L. Neuroendocrine tumours. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, et al., editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology & Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. IARC Press; Lyon, Frane: 2005. pp. 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu B, Chetty R, Perez-Ordonez B. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the head and neck: some suggestions for the new WHO classification of head and neck tumors. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:24–32. doi: 10.1007/s12105-014-0531-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kusafuka K, Ferlito A, Lewis JS, Jr., et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the head and neck. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis JS, Jr., Spence DC, Chiosea S, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx: definition of an entity. Head Neck Pathol. 2010;4:198–207. doi: 10.1007/s12105-010-0188-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kusafuka K, Abe M, Iida Y, et al. Mucosal large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the head and neck regions in Japanese patients: a distinct clinicopathological entity. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:704–709. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2012-200801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sturgis CD, Burkey BB, Momin S, et al. High Grade (Large Cell) Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Nasopharynx: Novel Case Report with Touch Preparation Cytology and Positive EBV Encoded Early RNA. Case Rep Pathol. 2015;2015:231070. doi: 10.1155/2015/231070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dumars C, Thebaud E, Joubert M, et al. Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Nasopharynx: A Pediatric Case. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2015;37:474–476. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elloumi F, Fourati N, Siala W, et al. [Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the nasopharynx: A case report] Cancer Radiother. 2014;18:208–210. doi: 10.1016/j.canrad.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersson F, Loh KS. Carcinosarcoma ex non-recurrent pleomorphic adenoma composed of TTF-1 positive large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and myofibrosarcoma: apropos a rare Case. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7:163–170. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0385-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Laan TP, Plaat BE, van der Laan BF, et al. Clinical recommendations on the treatment of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx: A meta-analysis of 436 reported cases. Head Neck. 2015;37:707–715. doi: 10.1002/hed.23666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halmos GB, van der Laan TP, van Hemel BM, et al. Is human papillomavirus involved in laryngeal neuroendocrine carcinoma? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:719–725. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2075-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kao HL, Chang WC, Li WY, et al. Head and neck large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma should be separated from atypical carcinoid on the basis of different clinical features, overall survival, and pathogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:185–192. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318236d822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larsson LG, Donner LR. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the parotid gland: fine needle aspiration, and light microscopic and ultrastructural study. Acta Cytol. 1999;43:534–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagao T, Sugano I, Ishida Y, et al. Primary large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the parotid gland: immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of two cases. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:554–561. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casas P, Bernaldez R, Patron M, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the parotid gland: case report and literature review. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2005;32:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ueo T, Kaku N, Kashima K, et al. Carcinosarcoma of the parotid gland: an unusual case with large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and rhabdomyosarcoma - Case report. Apmis. 2005;113:456–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2005.apm_231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel KJ, Chandana SR, Wiese DA, et al. Unusual presentation of large-cell poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma of the epiglottis. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:e461–463. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.6237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92:709–720. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.9.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singhi AD, Westra WH. Comparison of human papillomavirus in situ hybridization and p16 immunohistochemistry in the detection of human papillomavirus-associated head and neck cancer based on a prospective clinical experience. Cancer. 2010;116:2166–2173. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D'Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, et al. Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;356:1944–1956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis JS, Jr., Westra WH, Thompson LD, et al. The Sinonasal Tract: Another Potential “Hot Spot” for Carcinomas with Transcriptionally-Active Human Papillomavirus. Head Neck Pathol. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0514-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larque AB, Hakim S, Ordi J, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus is transcriptionally active in a subset of sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2013 doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bishop JA, Guo TW, Smith DF, et al. Human papillomavirus-related carcinomas of the sinonasal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:185–192. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182698673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100:261–269. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363:24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Westra WH. The morphologic profile of HPV-related head and neck squamous carcinoma: implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and clinical management. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(Suppl 1):S48–54. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0371-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonilla-Velez J, Mroz EA, Hammon RJ, et al. Impact of human papillomavirus on oropharyngeal cancer biology and response to therapy: implications for treatment. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2013;46:521–543. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, et al. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2004. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraft S, Faquin WC, Krane JF. HPV-associated neuroendocrine carcinoma of the oropharynx: a rare new entity with potentially aggressive clinical behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:321–330. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31823f2f17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bishop JA, Westra WH. Human papillomavirus-related small cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1679–1684. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182299cde. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Embry JR, Kelly MG, Post MD, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: prognostic factors and survival advantage with platinum chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;120:444–448. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grayson W, Rhemtula HA, Taylor LF, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus in large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a study of 12 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:108–114. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.2.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Omori M, Hashi A, Kondo T, et al. Successful neoadjuvant chemotherapy for large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: A case report. Gynecol Oncol Case Rep. 2014;8:4–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gynor.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan J, Knorr J, Altmannsberger M, et al. Expression of p16 and lack of pRB in primary small cell lung cancer. The Journal of pathology. 1999;189:358–362. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199911)189:3<358::AID-PATH452>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hiroshima K, Iyoda A, Shida T, et al. Distinction of pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma from small cell lung carcinoma: a morphological, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:1358–1368. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beasley MB, Lantuejoul S, Abbondanzo S, et al. The P16/cyclin D1/Rb pathway in neuroendocrine tumors of the lung. Human pathology. 2003;34:136–142. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2003.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dosaka-Akita H, Cagle PT, Hiroumi H, et al. Differential retinoblastoma and p16(INK4A) protein expression in neuroendocrine tumors of the lung. Cancer. 2000;88:550–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]