Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a neurodegenerative tauopathy associated with repetitive head impacts.1 Presently, CTE only can be diagnosed pathologically; however, research efforts, such as the ongoing Understanding Neurological Injury and Traumatic Encephalopathy (UNITE) Study,2 are investigating ways to diagnose CTE during life. As part of the UNITE Study, a panel of clinicians, blinded to neuropathology, make retrospective clinical consensus diagnoses using published criteria, including proposed clinical research criteria for CTE.3 Here, we present an informative case from the UNITE Study.

Report of a Case

A 25-year-old man with a congenital bicuspid aortic valve and a family history of addiction and depression died of cardiac arrest secondary to Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. He played American football for 16 years, beginning at age 6 years, including 3 years of Division I college football (red shirt, freshman, and sophomore) as a defensive linebacker and special teams player. He experienced more than 10 concussions, all while playing football, the first occurring at age 8 years and none resulting in hospitalization. During his freshman year of college, he had a concussion with momentary loss of consciousness followed by ongoing headaches, neck pain, blurry vision, tinnitus, insomnia, anxiety, and difficulty with memory and concentration. When he returned to play after a few days, symptoms persisted. A neurologist prescribed cyclobenzaprine and topiramate, which offered limited benefit. He stopped playing football at the beginning of his junior season owing to ongoing symptoms. He began failing courses despite having earned above-average grades in high school (3.8 GPA) and earlier in college. He left school with a GPA of 1.9, 12 credits short of earning his bachelor degree.

His symptoms persisted and included apathy, anhedonia, decreased appetite, hypersomnia, feelings of worthlessness, and passive suicidal ideations. He had difficulty maintaining a job and eventually stopped seeking employment. He began using marijuana daily to alleviate headaches and anxiety and to improve sleep. At age 23 years, he became verbally and physically abusive toward his wife, a change from his prior demeanor. At age 24 years, he underwent neuropsychological evaluation (Table). He became increasingly dependent on his wife, although basic activities of daily living remained intact.

Table. Neuropsychological Testinga.

| Test | Scoreb | Interpretationc |

|---|---|---|

| Intellectual functioning | ||

| WAIS-III/7 | ||

| Estimated visual IQ | 102 | Average |

| Estimated performance IQ | 100 | Average |

| Estimated full-scale IQ | 101 | Average |

| WTAR | 103 | Average |

| Memory | ||

| WMS-III | ||

| Logical memory I | 8 | Low average |

| Logical memory II | 8 | Low average |

| CVLT-II | ||

| Total trials 1-5 | 22 | Impaired |

| Trial 1 | 4 | Borderline |

| Trial 5 | 4 | Impaired |

| Short-delay free recall | 5 | Impaired |

| Short-delay cued recall | 5 | Impaired |

| Long-delay free recall | 4 | Impaired |

| Long-delay cued recall | 5 | Impaired |

| BVMT-R | ||

| Trial 1 | 8 | Average |

| Trial 2 | 10 | Average |

| Trial 3 | 11 | Average |

| Delayed recall | 11 | Average |

| Language | ||

| BNT-2 | 47 | Impaired |

| D-KEFS letter fluency | 26 | Low average |

| D-KEFS category fluency | 32 | Average |

| Attention/executive functioning | ||

| TMT | ||

| Part A speed (errors) | 14 s(0) | High average |

| Part B speed (errors) | 84 s(1) | Impaired |

| Symbol digit modalities test | ||

| Written | 36 | Impaired |

| Oral | 57 | Low average |

| Stroop color and word test | ||

| Word score | 46 | Average |

| Color score | 46 | Average |

| Color-word score | 51 | Average |

| Interference | 53 | Average |

| Visuospatial | ||

| Rey figure copy | 8 | Low average |

| BVMT-R copy | 12 | Within expectation |

| Judgment of line orientation | 28 | High average |

Abbreviations: BNT, Boston Naming Test; BVMT-R, Brief Visuospatial Memory Test–Revised; CVLT, California Verbal Learning Test; D-KEFS, Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System; TMT, Trail Making Test; WAIS, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; WMS, Wechsler Memory Scale; WTAR, Wechsler Test of Adult Reading.

Summary: Intelligence was average and reading ability was commensurate. Visuospatial abilities were average. There were deficits in verbal episodic encoding, although verbal episodic retrieval and visual memory were intact. There were deficits in set-shifting and processing speed. Selective attention was intact. There were deficits in naming. Letter and category fluency were intact.

All scores are raw, unless otherwise indicated.

Interpretations are based on normative data accounting for age and education level. Percentile conversions are as follows: very superior >98%; superior, 91%-97%; high average, 75%-90%; average, 25%-74%; low average, 9%-24%; borderline, 2%-8%; and impaired <2%.

His next of kin provided written informed consent for participation and brain donation. Institutional review board approval for brain donation was obtained through the Boston University Alzheimer’s Disease Center and CTE Program and the Bedford VA Hospital. Institutional review board approval for postmortem clinical record review, interviews with family members, and neuropathological evaluation was obtained through the Boston University School of Medicine.

Consensus members unanimously supported postconcussive syndrome (PCS) as the primary diagnosis, with possible CTE and major depression as contributing diagnoses. Although CTE was considered, the lack of delay in symptom onset, his young age, and his family history of depression reasoned against CTE as the primary diagnosis. Consensus members thought that neuropsychological performance, while impaired, did not discriminate postconcussive syndrome or major depression from CTE (Figure).

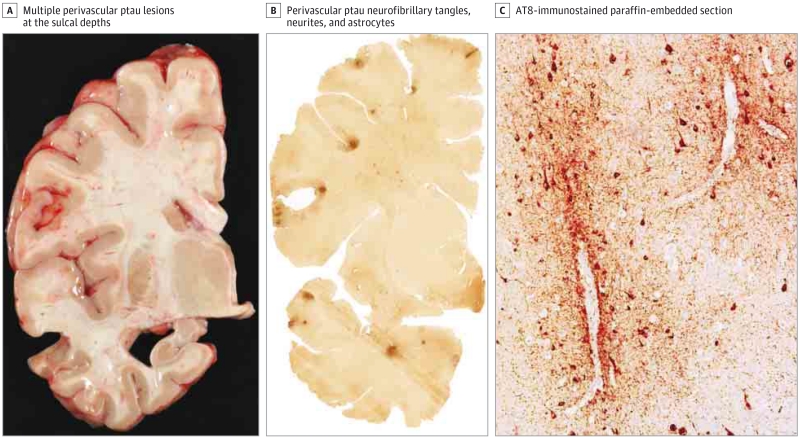

Figure 1. Neuropathological Findings of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

A, The brain showed mild ventricular dilation and hippocampal atrophy. Pathological lesions of hyperphosphorylated tau (ptau) consisting of neurofibrillary tangles, neurites, and astrocytes around small blood vessels were found at the sulcal depths of the frontal and temporal lobes. Free-floating 50-μm section immunostained for AT8 (B) and paraffin-embedded 10-μm section immunostained for AT8 (C; original magnification ×200). These ptau lesions are considered to be pathognomonic for CTE based on the preliminary National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke consensus criteria for the pathological diagnosis of CTE.1,5,6 Characteristic CTE ptau pathology was also found in the parietal lobes, entorhinal cortex, anterior hippocampus, hypothalamus, nucleus basalis of Meynert, substantia nigra, locus coeruleus, and median raphe. There was no immunopositivity for amyloid-β, TAR DNA-binding protein 43, or α-synuclein.

Discussion

Focal lesions of CTE have been found in athletes as young as 17 years1; however, widespread CTE pathology, as found in this case, is unusual in such a young football player. Although idiopathic depression and postconcussive syndrome commonly present in a similar fashion,4 the presence of widespread CTE pathology argues against but does not exclude them as potential etiologies of the clinical syndrome. While the case suggests that CTE should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a young adult with extensive repetitive head impact exposure and persistent mood and behavioral symptoms, it does not allow us to infer the likelihood of CTE in this setting.

While proposed clinical research criteria for CTE include impairment in memory and executive function on neuropsychological testing,3 to our knowledge, this is the first published case of pathologically confirmed CTE to include a neuropsychological test profile. It remains to be determined whether impairment in learning and executive function with preserved verbal episodic retrieval is a common presentation of CTE.

Studies of clinicopathological correlation, such as the UNITE Study,2 should help identify clinical features that are sensitive and specific for CTE pathology. Prospective studies that include neuropsychological testing with imaging and fluid biomarkers will be essential to future improvements in diagnosis of CTE during life.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This design and conduct of the study were supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grants 1UO1NS086659-01, R01NS078337, and R56NS078337), Department of Defense (grant W81XWH-13-2-0064), Department of Veterans Affairs, the Veterans Affairs Biorepository (grant CSP 501), the National Institute of Aging, Boston University Alzheimer’s Disease Center (grant P30AG13846; supplement 0572063345–5), Department of Defense Peer Reviewed Alzheimer’s Research Program (DoD-PRARP grant 13267017), the National Institute on Aging–Boston University Framingham Heart Study (grant R01AG1649), the National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment, and the Sports Legacy Institute. The collection and management of data were also supported by unrestricted gifts from the Andlinger Foundation, the WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment), and the National Football League.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funders had a role in the design and conduct of the study but not the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Additional Contributions: We thank Patrick T. Kiernan, BA, Lauren Murphy, BA, Philip H. Montenigro, BS, Victor E. Alvarez, MD, Lee E. Goldstein, MD, PhD, Douglas I. Katz, MD, Neil W. Kowall, MD, Robert C. Cantu, MD, and Robert A. Stern, PhD, of Boston University School of Medicine and Lisa McHale, BA, of the Concussion Legacy Foundation. Mr Kiernan conducts retrospective clinical interviews and participates in patient recruitment; Ms Murphy participates in patient recruitment; Mr Montenigro conducts retrospective clinical interviews; Dr Alvarez participates in pathological diagnosis; and Ms McHale participates in patient recruitment. They also made substantial contributions to study conception and design and drafting and critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content. Mr Kiernan, Ms Murphy, and Dr Alvarez received compensation for their contributions. Drs Goldstein, Katz, Kowall, Cantu, and Stern participate in clinical consensus diagnosis and made substantial contributions to conception and design and critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content. Compensation was received for such contributions. We gratefully acknowledge the use of the resources and facilities at the Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital (Bedford, Massachusetts). We also gratefully acknowledge the help of all members of the Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy Program at Boston University School of Medicine, the Boston VA, as well as the individuals and families whose participation and contributions made this work possible. We also thank the patient’s next of kin for granting permission to publish this information.

References

- 1.McKee AC, Stein TD, Nowinski CJ, et al. The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain. 2013;136(pt 1):43–64. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws307. doi:10.1093/brain/aws307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mez J, Solomon TM, Daneshvar DH, et al. Assessing clinicopathological correlation in chronic traumatic encephalopathy: rationale and methods for the UNITE Study. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0148-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montenigro PH, Baugh CM, Daneshvar DH, et al. Clinical subtypes of chronic traumatic encephalopathy: literature review and proposed research diagnostic criteria for traumatic encephalopathy syndrome. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6(5):68. doi: 10.1186/s13195-014-0068-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broshek DK, De Marco AP, Freeman JR. A review of post-concussion syndrome and psychological factors associated with concussion. Brain Inj. 2015;29(2):228–237. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2014.974674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKee AC, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, et al. The First NINDS/NIBIB Consensus Meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathologica. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1515-z. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shen H. Researchers seek definition of head-trauma disorder. Nature. 2015;518(7540):466–467. doi: 10.1038/518466a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]