Abstract

End-to-end connections between adjacent tropomyosin molecules along the muscle thin filament allow long-range conformational rearrangement of the multicomponent filament structure. This process is influenced by Ca2+ and the troponin regulatory complexes, as well as by myosin crossbridge heads that bind to and activate the filament. Access of myosin crossbridges onto actin is gated by tropomyosin, and in the case of striated muscle filaments, troponin acts as a gatekeeper. The resulting tropomyosin-troponinmyosin on-off switching mechanism that controls muscle contractility is a complex cooperative and dynamic system with highly nonlinear behavior. Here, we review key information that leads us to view tropomyosin as central to the communication pathway that coordinates the multifaceted effectors that modulate and tune striated muscle contraction. We posit that an understanding of this communication pathway provides a framework for more in-depth mechanistic characterization of myopathy-associated mutational perturbations currently under investigation by many research groups.

Keywords: Actin, cooperativity, myosin, tropomyosin, troponin, thin filament

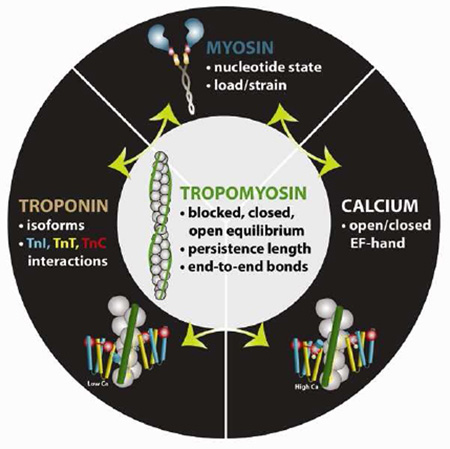

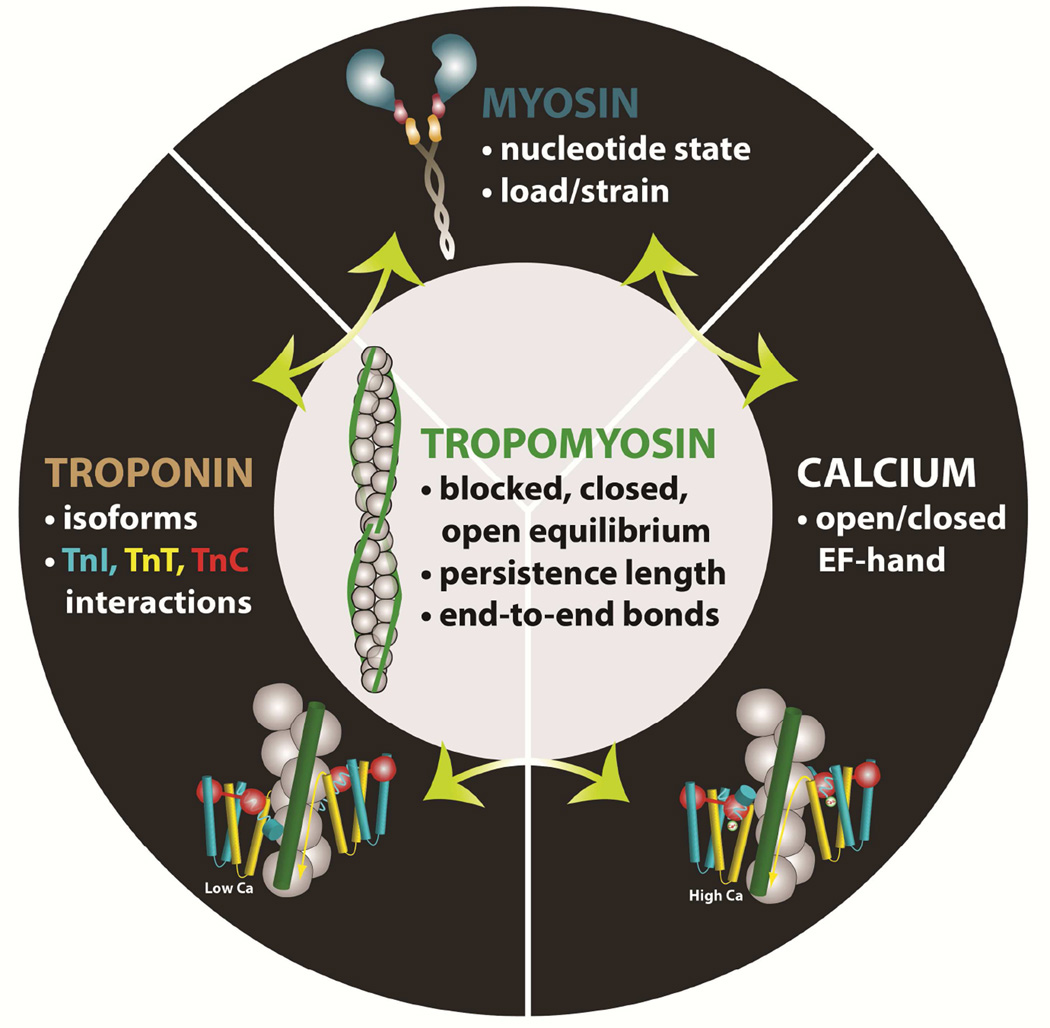

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Generation of contractile force by striated muscles relies on the relative sliding of the thick and thin filaments within myofibrillar sarcomeres. The sliding process, in turn, depends on ATP hydrolysis-coupled, cyclic interactions of the crossbridge heads of myosin molecules moving along successive actin subunits of thin filaments. This mechanochemical-linked enzymatic mechanism is at the core of muscle contractile force development. However, muscle force generation would be ineffective without a regulatory on-off switching mechanism or some form of fine-tuning to control the strength and duration of contraction. Indeed, in skeletal and cardiac muscles, and to some extent in non-sarcomeric smooth muscle, the contractile process is controlled sterically by a global repositioning of the regulatory protein, tropomyosin, over myosin-binding interaction sites on the actin subunits, which themselves form the backbone of the thin filament [1–6 and reviewed in 7–11]. This tropomyosin movement blocks interactions of the myosin crossbridge head on actin during relaxation and possibly even promotes them following activation [12]; hence the steric regulation consequently controls the crossbridge cycling that powers mechanical force for the contractile process. Here, the regulatory position of tropomyosin on thin filaments is defined by the influence of both Ca2+ binding to troponin and myosin binding to actin, thus forming the on-off switching mechanism. We propose that the high degree of cooperativity displayed by the switching mechanism is dependent on the global repositioning of the tropomyosin molecule over the actin filament.

Tropomyosin is a 40 nm long semi-rigid coiled-coil that extends over 7 actin subunits. By linking head-to-tail, tropomyosin builds a continuous cable along the entire length of the thin filament [6,9,13,14]. The binding of tropomyosin at any one point along F-actin is very weak and determined locally by a few electrostatic interactions [15–17]. Since tropomyosin is a semi-rigid coiled-coil [18], it therefore displays relatively high persistence length. Hence, in principle at least, the mechanical or chemical impact of troponin and/or myosin binding onto actin along the tropomyosin cable will be translated up and down the thin filament due to tropomyosin’s flexural stiffness. In this way, Ca2+-free troponin and myosin heads bound to actin bias and thereby effectively trap tropomyosin in one or another regulatory position on thin filaments. Thus, a simple cooperative on-off switching mechanism is expected to be associated with the propagated repositioning of semi-rigid tropomyosin on actin under the influence of troponin and myosin, explaining in part the steep rise and decline in tension of muscle fibers in response to small changes in Ca2+ concentration [19].

One can consider the binding of myosin onto actin and hence crossbridge cycling on thin filaments being gated by tropomyosin, with troponin, in the case of striated muscle filaments, playing the role of gatekeeper [19]. For this thin filament regulatory mechanism to operate effectively, tropomyosin is often described as fundamental to the cooperative, allosteric regulation of muscle contraction [20–24], with various levels of rigor applied to the description of the cooperativity and the allostery, beyond what was originally proposed [22].

In this review, we define the structural and functional determinants of tropomyosin-dependent thin filament allostery and cooperativity. We describe the unique characteristics and effects of tropomyosin and troponin on contractile behavior. We discuss, for example, that Ca2+ and myosin are allosteric effectors of troponin binding to actin and therefore associated with the shifting of tropomyosin positions. Thus, the allosteric influence of Ca2+ and myosin must also have sterically defined cooperative effects. In addition, while myosin and tropomyosin are, in fact, competitors for common binding-sites on actin, the interaction of tropomyosin on actin is not described by a typical lock-and-key stereospecific mechanism, whereas the strong binding of myosin on actin is stereospecific, and, when bound, myosin is an allosteric effector of remote actin sites, again leading to tropomyosin repositioning (and altering Ca2+ binding to troponin and troponin binding to actin). Again, the end result is steric and cooperative. Despite much conjecture (see reference [10] for review], the issue whether or not tropomyosin repositioning has an allosteric effect on actin subunit structure or subunit interactions within the thin filament has not been resolved directly, nor have allosteric effects of tropomyosin on ATP hydrolysis by myosin or on the dissociation of ADP-Pi from myosin been shown unequivocally. For example while controversial, there is evidence that the rate of phosphate release from thin filament-myosin-ADP-Pi complexes is a step in the crossbridge cycle regulated by Ca2+ and by myosin binding to thin filaments, whereas the affinity of myosin-ADP-Pi for the thin filament is less sensitive to Ca2+ [25]. The latter does not agree well with a strict interpretation of the steric blocking model, yet may be compatible with allosteric modulation of actin subunits of the thin filament. However, cryo-electron microscope reconstruction of actin subunit structure and F-actin organization appears to be the same whether or not tropomyosin is present on thin filament [26,27] diminishing the appeal of such a mechanism.

Calcium and myosin-binding regulate muscle contraction via tropomyosin

Troponin, the Ca2+-dependent modulator of tropomyosin behavior in skeletal and cardiac muscle, is itself a complex of three subunits (Fig. 1) [28]. Troponin T (TnT) links the troponin complex to tropomyosin; troponin I (TnI) effectively traps tropomyosin in a position blocking myosin binding to actin, and after binding Ca2+, TnC, the Ca2+-receptor, relieves the TnI imposed inhibition. There is one troponin complex for every seven actins along thin filaments [29]. The troponin complex is too short to interact with seven successive actin subunits in a 7 actin: 1 tropomyosin: 1 troponin “regulatory unit” [30]. Instead, Ca2+ binding to troponin indirectly affects actin-myosin interaction, filament sliding and hence muscle force generation by altering tropomyosin position on actin. A possibly cooperative but simple two-state on-off switching mechanism comes to mind. However, a strict two-state model found in many Cell Biology and Physiology textbooks does not satisfy the complexities of the allosteric feedback network built into the regulatory process.

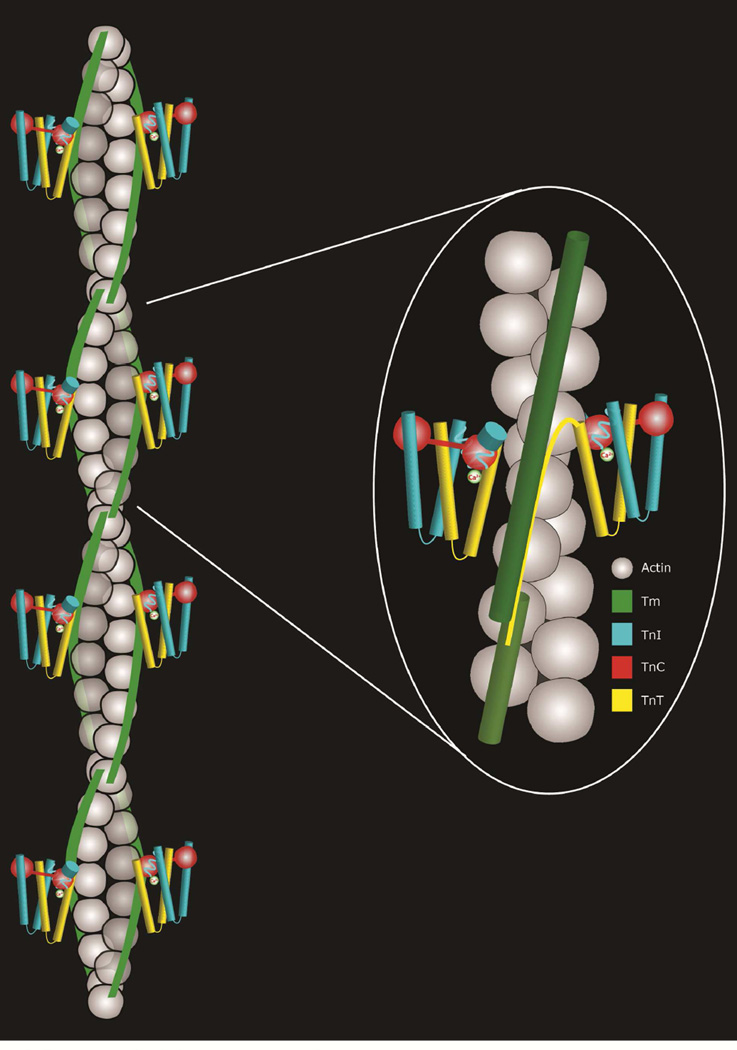

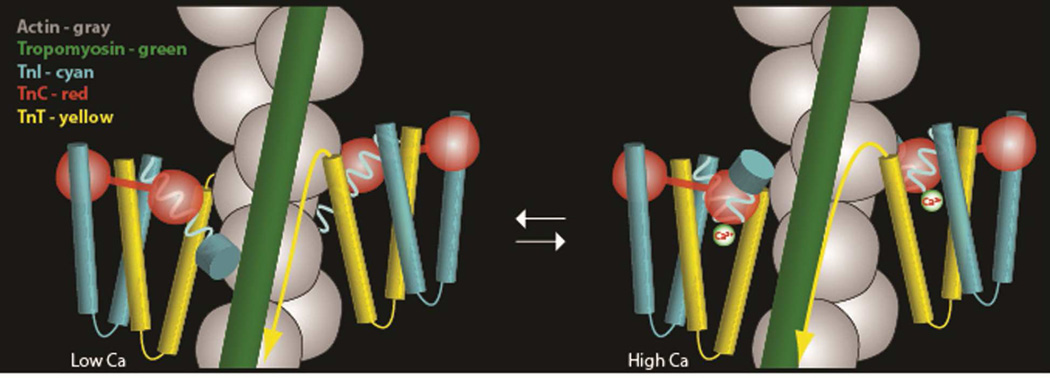

Figure 1.

Cartoon representation of the thin filament showing the double stranded helical array of actin subunits (gray), end-to-end bonded tropomyosin molecules (green) and the troponin complex (TnI, cyan; TnC, red; TnT, yellow). Left, four successive troponin-tropomyosin regulatory units on each actin helical strand; Right, enlargement of a portion of the cartoon.

Solution biochemistry defines a central role for tropomyosin in muscle regulation

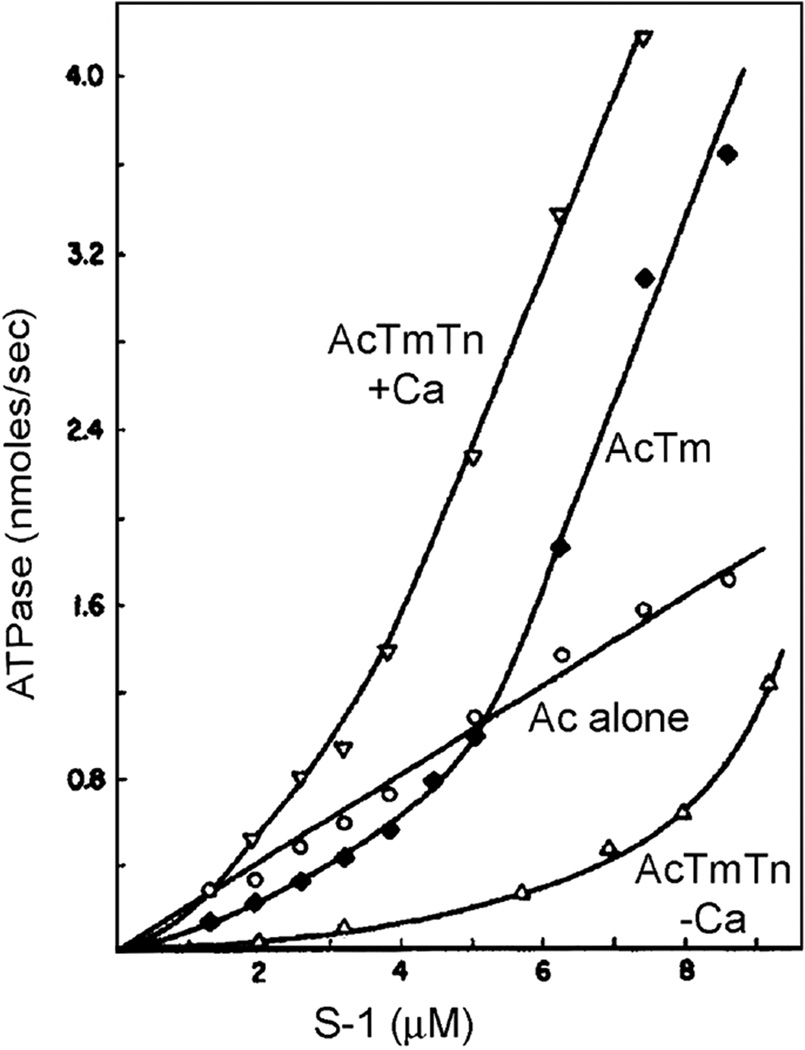

The myosin molecule can be cleaved proteolytically to yield soluble S1 fragments that represent the myosin crossbridge heads which are well-suited for studying the influence of troponin-tropomyosin on actin-myosin ATPase kinetics. At low myosin S1:actin ratios, Lehrer and Morris [31,32] showed that tropomyosin, irrespective of its source, inhibits actin-activated myosin ATPase. The effect is clearly observed under troponin-free conditions, but troponin amplifies the inhibition considerably. Thus, while troponin may effectively trap tropomyosin in a blocking position on actin, it is tropomyosin itself that causes the suppression of actin-myosin interactions. Conversely, at moderate to high S1:actin levels, the actin-tropomyosin filament activates the S1 ATPase even more than pure F-actin filaments do, until S1 saturation is reached. Thus, tropomyosin has both an inherent suppressing role which transforms to an activating one as myosin populates the actin filament. The resulting non-linear dependence of ATPase-activation on S1 concentration is strictly tropomyosin-dependent (Fig. 2). The dual effect of tropomyosin, and in particular the potentiation by troponin, is brought about by tropomyosin modulating the apparent affinity of actin for myosin by its varying position on actin filaments, as detailed below. The resulting non-linear binding of myosin to the thin filament is completely tropomyosin-dependent and fundamental to the cooperative switching mechanism regulating actin-myosin interaction.

Figure 2.

Dual effect of tropomyosin and troponin-tropomyosin on actomyosin subfragment 1 ATPase. Acto-S1 ATPase assays indicate that the troponin-tropomyosin regulated thin filament activation of myosin ATPase is Ca2+-dependent, while troponin-free F-actin or F-actin-tropomyosin activate the ATPase but confer no Ca2+-dependence. The activation of S1 ATPase by “unregulated” tropomyosin-free F-actin is linear as a function of added S1, yet sigmoidal when either tropomyosin or troponin-tropomyosin is present (saturation by very high S1 levels not shown). Thus, relative to control F-actin values, tropomyosin, in the presence and absence of troponin and Ca2+, inhibits actomyosin ATPase at low S1:F-actin ratios, and stimulates ATPase at high S1:F-actin ratios. Inhibition and activation by tropomyosin are greatest when troponin is present. Figure adapted, with permission, from reference [31]. This figure was originally published in The Journal of Biological Chemistry by S.S. Lehrer and E.P. Morris in an article “Dual effects of tropomyosin and tropomyosin-troponin on skeletal muscle subfragment 1 ATPase” J. Biol. Chem. 1982; 257:8073–8080 © the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

In vitro motility assays parallel solution biochemistry work

Following up on the above studies, in vitro motility assays using reconstituted or purified muscle thin filaments were also used to study the regulation of myosin action by the troponin-tropomyosin regulatory system, particularly since the method appropriately correlates myosin enzymatic activity and myosin-sponsored filament movement. Honda and Asakura [33] and Harada et al. [34] were among the first to use the assay to show skeletal muscle thin filament sliding over myosin is regulated by Ca2+ in vitro. In these studies, filaments exhibited no movement at low-Ca2+ (pCa>6), whereas filaments moved at maximum velocity at higher Ca2+ concentrations [33,34]. Later work showed a similar Ca2+-dependence for both the cardiac and skeletal muscle systems [35] and that both the fraction of motile filaments and the velocity of filament motion were Ca2+-sensitive. Moreover, maximal filament sliding velocity was shown to increase after the addition of tropomyosin or the tropomyosin-troponin complex [36–38], in a similar manner to that displayed by the actin-myosin ATPase, discussed above.

Myosin facilitating its own binding to actin is tropomyosin-dependent

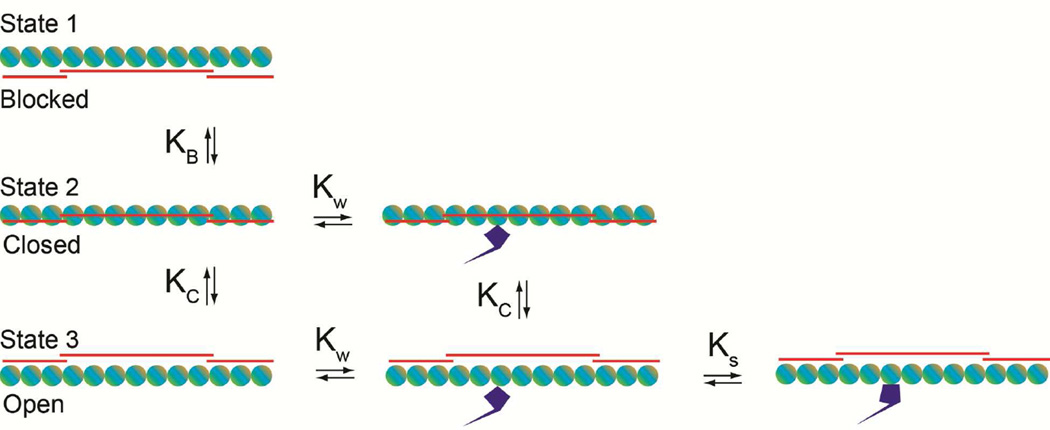

The dual inhibitory and potentiating effects of tropomyosin on actin-activation of myosin ATPase in part led McKillop and Geeves [39] to suggest a regulatory mechanism in which tropomyosin equilibrates between three functional states (Fig. 3) (reviewed in [40]). (Reference [40] also provides a useful appraisal of material discussed in [10,25].) In their model, relative occupancy of these states is biased by the respective effects of troponin, Ca2+-binding and myosin-interactions. Kinetic modeling of this process by McKillop-Geeves (extrapolated from studies carried out in the absence of ATP) suggested that the probability of small populations of myosin heads binding to actin increases as filaments are released from a “blocked” tropomyosin state to a “closed state” (promoted by Ca2+-binding), which then allows greater access of heads to neighboring unoccupied actin subunits [39,40]. (The term closed-state unfortunately is not intuitive, since structurally the myosin-binding site is largely unobstructed [41].) It follows that once myosin binds to actin, actin-tropomyosin becomes a better substrate for further myosin association on actin. The filament then “opens” leading to a cooperative transition to the fully active “myosin-induced” M-state [36]. Thus, while cooperative activation of the thin filament regulatory system is inherently tropomyosin-dependent, it can be tuned differentially by the effects of troponin, Ca2+ and myosin, in each of three functional states. The modeling suggested that Ca2+ binding to troponin is not sufficient to fully switch on thin filaments; i.e., Ca2+-activated thin filaments (viz. in high-Ca2+-induced “closed”-states) are, in fact, inactive. While functionally distinct from low-Ca2+ tropomyosin“blocked”-filaments (state 1), high-Ca2+ treated filaments (state 2) do not initially stimulate actin-myosin ATPase. Thus, the only functional thin filament configuration which fully activates the myosin ATPase is the so-called “open”-state of the filament, when both myosin and Ca2+ are bound to troponin-tropomyosin - regulated thin filaments (state 3)(Fig. 3). Moreover, a coupling of tropomyosin and myosin binding to actin accentuates the cooperativity since each may enhance the affinity of the other [26,42–44], which is partly responsible the sigmoidal relationship observed in Morris and Lehrer’s plots [31,32]. Still, when examining the ATPase interaction there may be some enhancement of Pi release by Ca2+.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the McKillop-Geeves three-state regulatory model of the thin filament. (A) Thin filament regulatory units consist of single lines depicting tropomyosin (red) over seven circles representing actin (aquamarine/tan); myosin is drawn as blue S1-like objects. Blocked, closed, open states (a.k.a. B-, C-, M-states [41]) are indicated. The dynamic equilibrium between states is illustrated as an azimuthal translocation of tropomyosin on actin and an isomerization of myosin into a strongly attached configuration. KB and KC identify equilibrium transitions between blocked and closed states, while KW and KS represent equilibria for initial weak and then strong myosin binding steps on actin.

As noted above, the terms “blocked”, “closed” and “open” can be confusing, since even though thin filaments in the closed state are inactive functionally, from a structural perspective the myosin-binding sites on the thin filaments are largely open (discussed later). While tropomyosin no is longer constrained by troponin in the closed-state, myosin interaction with actin is still hindered, as if “closed-off”, from transitioning to strong-binding on actin by tropomyosin. The myosin heads in the closed-state experience a problem a bit like the dilemma sometimes suffered by passengers seated in middle seats on an airplane when trying to reach the aisle. Their seat belt has been unbuckled, but a partial obstruction still remains.

In an attempt to formalize and clarify the description of thin filament states, generic terms were adopted over 15 years ago [41], “B” for blocked-state, “C” for closed-state and “M” for open-state [cf. 39,40]. But as pointed out by Mick Jagger and Dave Stewart, “old habits die hard, harder than November rain” and the traditional terms are still widely used.

The tropomyosin-dependence described above, defining how strong binding by myosin on actin drives cooperative activation of the muscle thin filament, has been known for over 40 years. In what are now regarded as classic studies, Bremel, Murray and Weber [45,46] showed that prolonged attachment of myosin on actin filaments, for example at low ATP, activates the filament despite low Ca2+ concentrations, provided tropomyosin is present. Thus in the presence of tropomyosin, myosin appears to potentiate its own binding cooperatively, again showing tropomyosin is critical for cooperative activation. In contrast, in the absence of tropomyosin, cooperative communication between actin subunits along F-actin is broken and myosin heads are not potentiated by their neighbors. Studies showing the tropomyosin-dependent potentiating effect of myosin-binding were later extended to skinned muscle fiber preparations in which force development was assessed in response to stepwise decreases in ATP concentration [47] or the addition of enzymatically inactive strong binding myosin analogs [48]. This work again confirmed that the thin filament is predominantly in an off state at low-Ca2+ and that myosin-binding onto actin is required to fully switch muscles to an on state. Hence, not only is tropomyosin critical to muscle’s on-off switching mechanism, but alterations in myosin mechanochemistry that influence the amount of strongly attached myosin crossbridges likely have a major impact on the regulation of muscle contraction. A very recent example showing the importance of myosin-induced contraction in membrane-permeabilized human cardiomyocytes again supports this view [49].

The role of strong myosin-binding in thin filament activation has also been investigated using in vitro motility assays. Here, myosin-binding to actin can be manipulated by varying myosin surface density or by the concentration of nucleotide products, viz. ADP. Consistent with fiber studies [50], the effects of myosin-binding on tropomyosin-dependent thin filament activation are greater at submaximal Ca2+ concentrations [38]. In addition, cooperativity and pCa50 (i.e. [Ca2+] exhibiting half-maximal activation) is a function of the myosin duty-ratio (i.e. the time myosin spends attached to actin, relative to the whole actin-myosin cycle) [38,51]. Therefore, changes in cooperative activation of the actin-myosin interaction can result directly from alterations in myosin-based activation rather than simply from changes in TnC affinity for Ca2+ [52–55].

The characterization of striated muscle regulation has relied primarily on solution biochemistry studies of myosin molecule ensembles or on assessing myosin molecules acting collectively within muscle fibers, making understanding of contraction and its regulation at the single molecule level challenging. Similarly, in vitro motility assays measure the action of clusters of myosin molecules interacting with actin or actin-tropomyosin filaments and not the action of single motor molecules. To be able to determine the molecular mechanism underlying the troponin-tropomyosin control of myosin binding to actin down to the molecule level at high spatial and temporal resolution, Kad et al. [56] used a laser trap assay, where pN forces developed by single or defined numbers of myosin molecules were measured on individual thin filaments. The studies showed that myosin binding to troponin-tropomyosin regulated thin filaments was dramatically reduced from ~2 binding events per second to <0.01 events per second at low-Ca2+ (pCa8) and that binding frequency could be restored at high-Ca2+ or by a 100-fold increase in myosin density. The laser trap studies additionally revealed that, even at low Ca2+ concentrations, the binding of a single myosin molecule accelerated the binding of neighboring myosin molecules to adjacent actin sites along troponin-tropomyosin regulated thin filaments. The tropomyosin-dependent cooperative activation of myosin-binding is consistent with solution studies [57,58] and, from a structural viewpoint, are consistent with the view that the binding of the initial myosin head may bias tropomyosin’s equilibrium position on actin and promote further myosin binding to adjacent actin subunits. The distance over which this cooperative activation extends along the thin filament was estimated to be within three tropomyosin-troponin regulatory units; i.e. stretching over ~20 consecutive actin subunits [56]. Further studies using single molecule imaging of fluorescently-labeled myosin binding to regulated filaments again confirmed that Ca2+ only partially activates the filament and that binding of single myosin molecules activates a local “patch” of actin where an additional 11 more myosin molecules can readily bind [59]. Because of the resolution limits of fluorescence microscopy, it was not possible to determine if binding of additional myosin heads on actin occurred directly adjacent to the initial binding events; however, since more myosin molecules were observed to bind than were blocked by a single tropomyosin molecule it was concluded that the cooperative unit extends beyond the boundary of a single tropomyosin molecule along the filament, consistent with structural [5] and biochemical studies [60,61] as well as skinned fiber work [62,63]. Remarkably, the locally-activated fluorescent myosin-binding patches were shown to grow, diffuse and catastrophically collapse with time. At high concentrations of myosin and Ca2+, the “active” regions grow and fuse, resulting in the entire filament being turned on, while alternatively, at low myosin levels the thin filament was poised to turn off even when Ca2+ was present [59,64].

Obviously, cooperative activation of the system goes hand in hand with cooperative inhibition as myosin dissociates from actin at low-Ca2+. In fact, energetic costs of Ca2+ cycling benefit from cooperative de-activation by minimizing the amount of Ca2+ that needs to be actively removed from the muscle cytoplasm during relaxation. Thus, modulation of the pCa50 for activation/relaxation provides a mechanism to fine tune the process. In cardiac muscle, for example, residual activity at low-Ca2+ has been proposed to be an important contributor to cardiac disease [65,66].

Correlation of thin filament structural and biochemical states

X-ray diffraction studies on intact muscle fibers indicate that the binding of Ca2+ to troponin induces changes in the relationship of tropomyosin and actin on thin filaments [1–3]. These studies formed the basis for the well-known steric-blocking model of muscle regulation which holds that tropomyosin strands running along thin filaments move 15° to 20° away from myosin-binding sites on actin when mu scle is activated, allowing crossbridge interaction and contraction to proceed, while at low-Ca2+ in relaxed muscle tropomyosin blocks access of myosin on actin. These studies are fully supported by electron microscope studies and corresponding three-dimensional reconstruction [4–6]. 3DEM of thin filaments shows that tropomyosin cables run continuously and in contact with successive actin subunits along the filament helical axes (Fig. 4). At low-Ca2+, filaments show tropomyosin traversing actin subdomains 1 and 2 on the outer aspect of actin, while covering the myosin-binding sites on subdomain 1. Under these low-Ca2+ conditions, tropomyosin is effectively trapped in this location on actin by a C-terminal domain of TnI which binds onto actin subdomain 3 and possibly to adjacent parts of tropomyosin [67–69]. In contrast, at high-Ca2+, an opening of a hydrophobic pocket on TnC and associated increased affinity for the C-terminal regulatory domain of TnI competes favorably and leads to TnC-TnI interaction and dissociation of the so-called mobile-domain of TnI from actin.[67–69]. All interactions of the regulatory network are likely to be in rapid equilibrium, and interactions of the TnI mobile regulatory domain with either actin-tropomyosin at low Ca2+ or TnC at high Ca2+ presumably are no different, as pointed out by Lehrer [21]. In essence, the effect of such TnI binding is to bias the system to either the blocked, B-state or the closed C-state, thereby regulating the initial weak binding of myosin to actin.

Figure 4.

Atomic coordinates of actin, tropomyosin and myosin based on single particle reconstructions of thin filaments [99]. Tropomyosin in its three average regulatory positions superposed on actin for comparison; tropomyosin shown in the blocking, closed and open states (red, yellow, green, respectively). Figure adapted, with permission, from [6].

Following release of TnI from actin, tropomyosin can then shift toward actin subdomain 3 and 4 and away from subdomain 1, hence exposing most of the myosin-binding site on actin, while potentially enhancing actin-myosin interaction (Fig. 5). However, despite the Ca2+-dependent movement of tropomyosin evident from these structural studies, the edge of the myosin-binding site remains obstructed following the tropomyosin shift, explaining the residual inhibition of actin-myosin interaction despite Ca2+ binding to troponin [5,6].

Figure 5.

Cartoon representations of the movement of tropomyosin under the influence of conformational changes in troponin dependent on Ca2+. Low-Ca2+ – left, High-Ca2+ – right. Figure from references [12] and [67] with permission. Note the movement of tropomyosin and the changing association of the TnI C-terminus (depicted as a disc), at low-Ca2+ associating with TnC and at high-Ca2+ with actin-tropomyosin.

Thus, the blocked, B-state, characterizing the solution studies of McKillop and Geeves [39–40] can be regarded as the functional correlate of the low-Ca2+ structural state determined by 3D reconstruction [4,5,6,41], namely when myosin cannot cycle on actin. Similarly, the closed, C-state can be considered the functional equivalent of the high-Ca2+ thin filament configuration described by 3D reconstruction. The closed-state will predominate when Ca2+ is bound to troponin, but before myosin has attached strongly to actin; it represents an intermediate step in the activation process [5,6,27,39–41].

Fiber diffraction studies and 3DEM indicate a further shift in tropomyosin position occurs when myosin begins to bind to actin-tropomyosin (Fig. 4). In fact, 3DEM of thin filaments decorated with sub-saturating levels of S1 reveals that up to 3 successive tropomyosin molecules in a tropomyosin cable all move together in response to the binding of a single S1 on F-actin [5,6], correlating with the above mentioned single molecule myosin-binding measurements [59]. Again these results indicate that myosin facilitates its own binding cooperatively through tropomyosin-tropomyosin connections. The underlying cooperativity can be easily explained if the tropomyosin molecule is semi-rigid, as EM data and Molecular Dynamics simulations indicate [14,15,17,18], since the binding of small numbers of S1 heads in the C-state will move tropomyosin and open the filament locally.

Ca2+-binding signaling is transmitted cooperatively along thin filaments via tropomyosin

Direct detection of the cooperative spread of activation between troponin-tropomyosin regulatory units along the thin filament was accomplished using troponin labeled with fluorophores sensitive to Ca2+-binding. These studies demonstrated a degree of Ca2+-binding cooperativity along the thin filament [52,70]. Indeed, this cooperativity, particularly for labeled cardiac troponin containing one regulatory Ca2+-binding site, argues for propagated activation between regulatory units either via end-to-end linked tropomyosin strands or by actin–actin interactions [70]. More recent results [71], using bifunctional orientation-sensitive probes to measure TnC structural changes during cardiac fiber Ca2+-activation, also provide support for a cooperative process intrinsic to the thin filament under physiological conditions, and that under pathological conditions in which myosin crossbridges cycle slowly (e.g., high ADP and/or low ATP), myosin affects TnC conformation and cooperative activation differently [71]. Thus, models of muscle Ca2+-regulation must be constrained by an understanding of both myosin crossbridge-dependent and crossbridge-independent cooperativity.

Tropomyosin governs thin filament regulation

We take a tropomyosin-centric view of muscle regulation, viz. all regulatory effects of Ca2+-bound and free troponin as well as those derived from myosin-binding and/or other ancillary binding proteins (such as myosin-binding protein-C) that we have described effect the lines of communication transmitted by tropomyosin along the thin filament. We consider that tropomyosin forms a continuous rather stiff cable with little decrement in mechanical properties across its head-to-end linkages, while being reinforced by Ser283 phosphorylation and by the additional presence of troponin-T [72,73]. The tropomyosin-based cooperativity in turn relies on the mechanical stiffness inherent to tropomyosin’s coiled-coil structure. The persistence length of tropomyosin determines the distance along the isolated molecule that “senses” perturbations of tropomyosin azimuthal position induced by troponin or myosin. The persistence length of tropomyosin is generally held to be considerably longer than a single regulatory unit consisting of one tropomyosin molecule and an associated troponin. Thus, the movement of tropomyosin by a single troponin and/or myosin molecule will spread over a longer distance than the length of the regulatory unit, unless such movement is dampened significantly by interactions with the actin filament substrate. The extent to which the association of tropomyosin on actin, however weak, will dampen the response of tropomyosin to flexural perturbation is not known. Conspicuously, structural and computational work indicate that at the end of contraction and beginning of relaxation tropomyosin will likely snap back from the now myosin-free M-state abruptly to the B-state, like releasing a guitar string under tension, interfering with further myosin-binding and contraction [17,74].

The end-to-end binding of tropomyosin molecules along the actin filament is designed to produce a high collective overall affinity of the polymerized tropomyosin cable, ensuring that it remains associated with the actin filament. In an apparent instance of obligate mutualism, the tropomyosin cable requires an F-actin substrate to remain fully polymerized, while the F-actin filament requires tropomyosin to enhance its stability and stiffness. However, the affinity of individual tropomyosin molecules for actin is very weak, and therefore permissive of local azimuthal regulatory movement of tropomyosin over actin at low energy cost. It follows that tropomyosin’s regulatory movements can extend further than the one tropomyosin protomer per seven actin multimer unit. Indeed, models of muscle regulation representing tropomyosin as a continuous chain along the actin filament describe many of the Ca2+-dependent properties of the regulated muscle thin filament [75–77].

In principle, cooperative activation of the thin filament could also depend on coupling of the two low-affinity Ca2+-binding sites on skeletal muscle TnC. Still, cardiac TnC and many invertebrate muscle TnC homologues bind a single Ca2+, and little evidence suggests that the cooperative binding of the two Ca2+ ions to skeletal muscle TnC is sufficient to explain cooperative muscle activation [52,78,79]. However, tropomyosin movement possibly promoting dissociation of the regulatory C-terminal domain of TnI from actin may enhance the likelihood of TnI binding to TnC to increase TnC Ca2+-sensitivity and indirectly affect thin filament cooperativity [21,80].The allostery and cooperativity of the regulatory process therefore depends on (1) the kinetics of the changes in tropomyosin location and the Ka characteristics of tropomyosin on actin, (2) the reversible binding association of TnI either to TnC and or to actin-tropomyosin and the kinetics of the corresponding transition, and (3) the transients involved in myosin binding to actin and their impact on troponin-tropomyosin (Fig. 6). While there may be little direct, hard evidence for substantial cooperative binding of Ca2+ to TnC being a dominant factor, the interdependent network of players in the regulatory switching mechanism is extremely complex. For example, Ca2+-binding-induced opening of a cleft in TnC allows access of the “switch peptide” domain of TnI, and thereby promotes dissociation of TnI from its inhibitory position on actin [67–69]. At the same time, opening of the TnC cleft may increase the affinity of TnC for Ca2+ by a factor of about 10 [45,81,82]. The interplay of this part of the system therefore can be thought of as a classical Monod-Wyman-Changeux cooperative/allosteric model [83] with open and closed TnC states, while Ca2+ and TnI act as allosteric effectors, which in turn are modulated by the repositioning of tropomyosin.

Figure 6.

The interconnected effects of thin filament cooperative activation operate through tropomyosin. Several effectors, acting through tropomyosin, contribute to cooperative activation of the striated muscle thin filament. Tropomyosin exists in three equilibrium states: blocked, closed, and open that control access of myosin to its binding site on actin. Calcium-binding to TnC, which is itself moderately cooperative in skeletal muscle, shifts the equilibrium via the multicomponent troponin complex allowing myosin to bind weakly to actin. Myosin-binding shifts tropomyosin further over actin exposing neighboring binding sites on actin, which can slightly increase Ca2+-binding by the thin filament. The predominant player in the final step of cooperative activation appears to be strongly attached myosin molecules on actin that perturb tropomyosin-defined regulatory units locally, thereby increasing myosin-attachment in neighboring units by shifting tropomyosin. The efficacy of this cooperative switching mechanism of tropomyosin depends on the degree and duration of strongly bound actin-myosin attachments, the tropomyosin flexibility and the tropomyosin-tropomyosin end-to-end bond strength along the end-to-end linked tropomyosin cable on the thin filament.

Consistent with the above structural, biochemical and physiological characteristics of the thin filament myosin interaction, factors that increase actin-myosin interactions (e.g., low-ATP and/or high-ADP concentrations) confer increased Ca2+-sensitivity to muscle preparations. Alternatively, conditions that reduce myosin-binding (high Pi concentration, myosin inhibitors) tend to reduce Ca2+-sensitivity. Similarly, factors that affect propagation of Ca2+ signals along the thin filament (e.g., tropomyosin stiffness and tropomyosin-tropomyosin end-to-end bond strength) would also alter the propagation of cooperative Ca2+-binding along the filament. Each of these variables is interconnected with the other but, with the exception of myosin linkages to actin following ATP hydrolysis, none of the multi-faceted binding associations involved have a high Ka. Therefore, the proteins of the thin filament regulatory system can be described by a collection of weakly bound two- or three-state allosteric switches (Fig. 6). For example as mentioned, the Ca2+-binding EF-hand on TnC exists in at least two states; an open-state with high affinity for Ca2+ and a closed-state, which has low affinity. In addition, Ca2+ influences TnC and the switch peptide of TnI, a specific region of the subunit, to bias TnC toward its open-state. In contrast, actin competes with TnC for binding of a distinct C-terminal mobile domain of TnI but cannot bind to TnI when the switch peptide is linked to TnC. Similarly, myosin, tropomyosin and TnI can compete with each other for specific sites on actin. Conversely, when Ca2+ binds to TnC, TnI instead binds to TnC and the thin filament becomes activated, allowing tropomyosin to translocate and myosin to gain access to its binding sites on actin. As mentioned, the resulting cooperative activation of the thin filament extends beyond a single seven actin tropomyosin-troponin regulatory unit. In turn, the degree of switching will depend on the rigidity of the tropomyosin molecule and the strength of end-to-end Tm-Tm interactions.

Any effector that increases the binding duration of myosin on actin in the poised regulatory equilibrium can, through interactions with TnI, alter the affinity of TnC for Ca2+ [84]. All else being equal, a longer relative duration in which myosin remains strongly bound on thin filaments must shift pCa50 to lower Ca2+ concentrations making the system more Ca2+-sensitive, and at the same time more difficult to switch off. Given the delicate balance between members of the multicomponent regulatory system, specific isoforms of thin filament regulatory proteins likely evolved to match myosin isoform kinetics while keeping Ca2+-sensitivity within its physiological range. Indeed, muscle- and development-specific isoforms of troponin, tropomyosin and myosin have been identified [85–89], consistent with the notion that troponin-tropomyosin interaction equilibria are paired with myosin kinetics. Interestingly, isoform specificity is typically associated with the entire tropomyosin-troponin complex rather than with a single subunit (e.g., TnC, TnI or TnT) and correlates with specific myosin isoforms.

The sensitive balance between members of the multicomponent regulatory system described here is further underscored by the fine-tuning of the regulatory system by phosphorylation of TnI, TnT and tropomyosin itself. Other yet to be fully described chemo-mechanical operators may also be significant effectors. For example, subtle differences in acid-base balance may impact charged residues along tropomyosin and, in turn, modify key electrostatic interactions between actin and tropomyosin [90]. The sensitivity to pH or to related cytosolic factors might vary among tropomyosin isoforms and the responses adapted to modulate the equilibrium between B-, C- and M-states. In addition, it is very likely that myopathic mutations will result in an imbalance in regulatory positioning of troponin-tropomyosin on actin, and the regulatory networks involved. In many cases, mutant charge reversals in the regulatory proteins appear to have complex delocalized effects quite remote from the affected regions, and therefore influence tropomyosin cooperativity indirectly. In a system as complex as the thin filament cooperative network, things aren’t always what they seem.

It is for precisely this reason that beginning with Hill, Eisenberg and Greene [91,92] many researchers over the years have chosen to generate mathematical models of myofilament activation as a means of testing hypothesized mechanisms. Models enable simultaneous representation of the multiple kinetic steps and regulatory states discussed here, which are sufficiently numerous to defy simple intuition. Aside from the considerable insight obtained through the model of McKillop and Geeves [39,40], several other models, and particularly those representing full-length thin filaments with interconnected regulatory units, have contributed to our understanding of myofilament cooperativity (reviewed by Rice and de Tombe [93]). For instance, the Ising-type model advanced by Rice et al. [94] demonstrated that a chain of interlinked regulatory units obeying simple neighbor-dependent state transitions displays cooperative Ca2+-dependent behavior that is consistent with experiments. The so-called continuous flexible chain models of Smith and Geeves [75,76] also produce realistic steady state behavior. These models, and others that they inspired [64,95–97] have been used to examine the interplay between tropomyosin-tropomyosin coupling, myosin duty ratio, and TnC-Ca2+ binding affinity among others. Some model insights include the result that myosin-binding only increases cooperativity (in terms of nH, the Hill coefficient of steady-state force) when strong tropomyosin-tropomyosin interactions are also present [95]. In this manner, tropomyosin-tropomyosin coupling acts to enhance the activating effects of myosin. Simulations also demonstrate that nearest-neighbor coupling is sufficient to reproduce the steep Ca2+-dependence of the rate of force redevelopment (ktr) in addition to cooperative Ca2+-dependence of steady-state force [95–97]. This time-dependent effect is potentially important to consider, in so far as the models predict that the slow rate of force development at low Ca2+ is the result of gradual recruitment of binding sites along the filament. When nearest-neighbor interactions are severed in the model, the rate of force development increases at sub-maximal Ca2+. Thus, quantitative simulations of the thin filament demonstrate that many Ca2+-binding sites, interconnected by tropomyosins, are capable of producing a broad range of emergent behaviors that are also observed in real muscle fibers.

In summary, both biochemical and structural studies, as well as modeling, define states of activation of the thin filament that are in rapid equilibrium and that are governed by the position of tropomyosin on actin. Calcium shifts this equilibrium such that myosin molecules can bind; however, strong cooperative binding occurs with a myosin-induced shift of tropomyosin to the open position. The extent of tropomyosin-based cooperative switching depends on tropomyosin stiffness as well as the strength of tropomyosin end-to-end bonds. Cooperative activation varies between muscle types and likely results from differences in thin filament regulatory protein and myosin isoforms (Fig. 6).

Highlights.

Tropomyosin is the focus of a cooperative thin filament communication network.

3 states of activation of the thin filament are in rapid equilibrium in Ca2+.

Ca2+-linked troponin shifts the equilibrium so myosin molecules bind to actin.

Myosin shifts tropomyosin to an “open” position to activate the thin filament.

The influence of Ca2+ and myosin is transmitted cooperatively by tropomyosin.

Tuning of tropomyosin behavior defines muscle isotype cooperative activation.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by NIH grants R01HL077280 (to J.R.M.), R21HL126025 (to S.G.C), R37HL036153 (to W.L.) and CTSA grant UL1TR000142 (to S.G.C.) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), an NIH component.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Haselgrove JC. X-ray evidence for a conformational change in actin-containing filaments of vertebrate striated muscle. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 1972;37:341–352. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huxley HE. Structural changes in actin and myosin-containing filaments during contraction. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 1972;37:361–376. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parry DAD, Squire JM. Structural role of tropomyosin in muscle regulation: Analysis of the X-ray diffraction patterns from relaxed and contracting muscles. J. Mol. Biol. 1973;75:33–55. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90527-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lehman W, Craig R, Vibert P. Ca2+-induced tropomyosin movement in Limulus thin filaments revealed by three-dimensional reconstruction. Nature. 1994;368:65–67. doi: 10.1038/368065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vibert P, Craig R, Lehman W. Steric-model for activation of muscle thin filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;266:8–14. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poole KJ, Lorenz M, Evans G, Rosenbaum G, Pirani A, Tobacman LS, Lehman W, Holmes KC. A comparison of muscle thin filament models obtained from electron microscopy reconstructions and low-angle X-ray fibre diagrams from non-overlap muscle. J. Struct. Biol. 2006;155:273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tobacman LS. Thin filament-mediated regulation of cardiac contraction. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1996;58:447–481. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.002311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon AM, Homsher E, Regnier M. Regulation of contraction in striated muscle. Physiol. Rev. 2000;80:853–924. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown JH, Cohen C. Regulation of muscle contraction by tropomyosin and troponin: how structure illuminates function. Adv. Protein Chem. 2005;71:121–159. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(04)71004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nevzorov IA, Levitsky DI. Tropomyosin: Double helix from the protein world. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2011;76:1507–1527. doi: 10.1134/S0006297911130098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khaitlina SY. Tropomyosin as a Regulator of Actin Dynamics. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2015;318:255–291. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehman W, Galińska-Rakoczy A, Hatch V, Tobacman LS, Craig R. Structural basis for the activation of muscle contraction by troponin and tropomyosin. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;388:673–681. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hitchcock-DeGregori SE. Tropomyosin: Function follows form. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2008;644:60–72. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-85766-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orzechowski M, Li XE, Fischer S, Lehman W. An atomic model of the tropomyosin cable on F-actin. Biophys. J. 2014;107:694–699. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li XE, Tobacman LS, Mun JY, Craig R, Fischer S, Lehman W. Tropomyosin position on F-actin revealed by EM reconstruction and computational chemistry. Biophys. J. 2011;100:1005–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.12.3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sunitha SM, Mercer JA, Spudich JA, Sowdhamini R. Integrative structural modelling of the cardiac thin filament: Energetics at the interface and conservation patterns reveal a spotlight on period 2 of tropomyosin. Bioinform. Biol. Insights. 2012;6:203–223. doi: 10.4137/BBI.S9798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orzechowski M, Moore JR, Fischer S, Lehman W. Tropomyosin movement on F-actin during muscle activation explained by energy landscapes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014;545:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li XE, Holmes KC, Lehman W, Jung H, Fischer S. The shape and flexibility of tropomyosin coiled coils: Implications for actin filament assembly and regulation. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;395:327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmes KC, Lehman W. Gestalt-binding of tropomyosin to actin filaments. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2008;29:213–219. doi: 10.1007/s10974-008-9157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Mezgueldi M M. Tropomyosin dynamics. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motility. 2014;35:203–210. doi: 10.1007/s10974-014-9377-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehrer SS. The 3-state model of muscle regulation revisited: is a fourth state involved? J. Muscle Res. Cell Motility. 2011;32:203–208. doi: 10.1007/s10974-011-9263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lehrer SS, Geeves MA. The muscle thin filament as a classical cooperative/allosteric regulatory system. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;277:1081–1089. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li KL, Rieck D, Solaro RJ, Dong W. In situ time-resolved FRET reveals effects of sarcomere length on cardiac thin-filament activation. Biophys. J. 2014;107:682–693. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marston S, Gautel M. Introducing a special edition of the Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility on tropomyosin: Form and function. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motility. 2013;34:151–153. doi: 10.1007/s10974-013-9361-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heeley DH, Belknap B, White HD. Mechanism of regulation of phosphate dissociation from actomyosin-ADP-Pi by thin filament proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:16731–16736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252236399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Behrmann E, Müller M, Penczek PA, Mannherz HG, Manstein DJ, Raunser S. Structure of the rigor actin-tropomyosin-myosin complex. Cell. 2012;150:327–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von der Ecken J, Müller M, Lehman W, Manstein DJ, Penczek PA, Raunser S. Structure of the F-actin-tropomyosin complex. Nature. 2014;519:114–117. doi: 10.1038/nature14033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greaser ML, Gergely J. Purification and properties of the components from troponin. J. Biol. Chem. 1971;246:4226–4233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potter JD. The content of troponin, tropomyosin, actin and myosin in rabbit skeletal myofibrils. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1974;162:436–441. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(74)90202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flicker PF, Phillips GN, Jr, Cohen C. Troponin and its interactions with tropomyosin. An electron microscope study. J. Mol. Biol. 1982;162:495–501. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90540-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehrer SS, Morris EP. Dual effects of tropomyosin and troponin-tropomyosin on actomyosin subfragment 1 ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:8073–8080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lehrer SS, Morris EP. Comparison of the effects of smooth and skeletal tropomyosin on skeletal actomyosin subfragment 1 ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:2070–2072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Honda H, Asakura S. Calcium-triggered movement of regulated actin in vitro. A fluorescence microscopy study. J. Mol. Biol. 1989;205:677–683. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harada Y, Sakurada K, Aoki T, Thomas DD, Yanagida T. Mechanochemical coupling in actomyosin energy transduction studied by in vitro movement assay. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;216:49–68. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sata M, Yamashita H, Sugiura S, Fujita H, Momomura S, Serizawa T. A new in vitro motility assay technique to evaluate calcium sensitivity of the cardiac contractile proteins. Pflügers Arch. 1995;429:443–445. doi: 10.1007/BF00374162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fraser ID, Marston SB. In vitro motility analysis of actin-tropomyosin regulation by troponin and calcium. The thin filament is switched as a single cooperative unit. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:7836–7841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.14.7836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Homsher E, Lee DM, Morris C, Pavlov D, Tobacman LS. Regulation of force and unloaded sliding speed in single thin filaments: Effects of regulatory proteins and calcium. J. Physiol. 2000;524:233–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gorga JA, Fishbaugher DE, VanBuren P. Activation of the calcium-regulated thin filament by myosin strong binding. Biophys. J. 2003;85:2484–2491. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74671-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKillop DF, Geeves MA. Regulation of the interaction between actin and myosin subfragment 1: Evidence for three states of the thin filament. Biophys. J. 1993;65:693–701. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81110-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geeves MA. Thin filament regulation. In: Egelman EH, Goldman YE, Ostap EM, editors. Comprehensive Biophysics, Vol 4, Molecular Motors and Motility. Oxford: Academic Press; 2012. pp. 251–267. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lehman W, Hatch V, Korman V, Rosol M, Thomas L, Maytum R, Geeves MA, Van Eyk JE, Tobacman LS, Craig R. Tropomyosin and actin isoforms modulate the localization of tropomyosin strands on actin filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;302:593–606. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tao T, Lamkin M. Crosslinking of tropomyosin to myosin subfragment-1 in reconstituted rabbit skeletal thin filaments. F.E.B.S. Lett. 1984;168:169–173. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80229-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tobacman LS, Butters CA. A new model of cooperative myosin-thin filament binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:27587–27593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Golitsina NL, Lehrer SS. Smooth muscle alpha-tropomyosin crosslinks to caldesmon, to actin and to myosin subfragment 1 on the muscle thin filament. F.E.B.S. Lett. 1999;463:146–150. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01589-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bremel RD, Weber A. Cooperation within actin filament in vertebrate skeletal muscle. Nat. New Biol. 1972;238:97–101. doi: 10.1038/newbio238097a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murray JM, Weber A. Molecular control mechanisms in muscle contraction. Physiol. Rev. 1973;53:612–673. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1973.53.3.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Metzger JM. Myosin binding-induced cooperative activation of the thin filament in cardiac myocytes and skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys. J. 1995;68:1430–1442. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80316-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swartz DR, Moss RL. Influence of a strong-binding myosin analogue on calcium-sensitive mechanical properties of skinned skeletal muscle fibers. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:20497–20506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sequeira V, Najafi A, Wijnker PJM, dos Remedios CG, Michels Diederik M, Kuster WD, van der Velden J. ADP-stimulated contraction: A predictor of thin-filament activation in cardiac disease V. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112:E7003–E7012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513843112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Swartz DR, Moss RL. Strong binding of myosin increases shortening velocity of rabbit skinned skeletal muscle fibres at low levels of Ca2+ J. Physiol. 2001;533:357–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0357a.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Webb M M, Jackson del R, Jr, Stewart TJ, Dugan SP, Carter MS, Cremo CR, Baker JE. The myosin duty ratio tunes the calcium sensitivity and cooperative activation of the thin filament. Biochemistry. 2013;52:6437–6444. doi: 10.1021/bi400262h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grabarek Z, Grabarek J, Leavis PC, Gergely J. Cooperative binding to the Ca2+-specific sites of troponin C in regulated actin and actomyosin. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:14098–14102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grabarek Z, Tao T, Gergely J. Molecular mechanism of troponin-C function. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motility. 1992;3:383–393. doi: 10.1007/BF01738034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guth K, Potter JD. Effect of rigor and cycling cross-bridges on the structure of troponin C and on the Ca2+ affinity of the Ca2+-specific regulatory sites in skinned rabbit psoas fibers. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:13627–13635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kreutziger KL, Piroddi N, Scellini B, Tesi C, Poggesi C, Regnier M. Thin filament Ca2+ binding properties and regulatory unit interactions alter kinetics of tension development and relaxation in rabbit skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2008;586:3683–3700. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.152181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kad KM, Kim S, Warshaw DM, VanBuren P, Baker JE. Single-myosin crossbridge interactions with actin filaments regulated by troponin-tropomyosin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:16990–16995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506326102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trybus KM, Taylor EW. Kinetic studies of the cooperative binding of subfragment 1 to regulated actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1980;77:7209–7213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Greene LE, Eisenberg E. Cooperative binding of myosin subfragment-1 to the actin-troponin-tropomyosin complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1980;77:2616–2620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Desai R, Geeves MA, Kad NM. Using fluorescent myosin to directly visualize cooperative activation of thin filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:1915–1925. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.609743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Geeves MA, Lehrer SS. Dynamics of the muscle thin filament regulatory switch: the size of the cooperative unit. Biophys. J. 1994;67:273–282. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80478-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maytum R, Lehrer SS, Geeves MA. Cooperativity and switching within the three-state model of muscle regulation. Biochemistry. 1999;38:1102–1110. doi: 10.1021/bi981603e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Regnier M, Rivera AJ, Chase PB, Smillie LB, Sorenson MM. Regulation of skeletal muscle tension redevelopment by troponin C constructs with different Ca2+ affinities. Biophys. J. 1999;76:2664–2672. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77418-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Regnier M M, Rivera AJ, Wang CK, Bates MA, Chase PB, Gordon AM. Thin filament near-neighbour regulatory unit interactions affect rabbit skeletal muscle steady-state force-Ca2+ relations. J. Physiol. 2002;540:485–497. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Walcott S, Kad NM. Direct measurements of local coupling between myosin molecules are consistent with a model of muscle activation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015;11:e1004599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lehrer SS, Geeves MA. The myosin-activated thin filament regulatory state, M--open: A link to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) J. Muscle Res. Cell Motility. 2014;35:153–160. doi: 10.1007/s10974-014-9383-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tardiff JC. Sarcomeric proteins and familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: linking mutations in structural proteins to complex cardiovascular phenotypes. Heart Failure Rev. 2005;10:237–248. doi: 10.1007/s10741-005-5253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Galińska-Rakoczy A, Engel P, Xu C, Jung H, Craig R, Tobacman LS, Lehman W. Structural basis for the regulation of muscle contraction by troponin and tropomyosin. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;379:929–935. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Murakami K, Yumoto F, Ohki SY, Yasunaga T, Tanokura M, Wakabayashi T. Structural basis for Ca2+-regulated muscle relaxation at interaction sites of troponin with actin and tropomyosin. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;352:178–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang S, Barbu-Tudoran L, Orzechowski M, Craig R, Trinick J, White H, Lehman W. Three-dimensional organization of troponin on cardiac muscle thin filaments in the relaxed state. Biophys. J. 2014;106:855–864. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tobacman LS, Sawyer D. Calcium binds cooperatively to the regulatory sites of the cardiac thin filament. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:931–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sun YB, Lou F, Irving M. Calcium- and myosin-dependent changes in troponin structure during activation of heart muscle. J. Physiol. 2009;587:155–163. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.164707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sousa D, Cammarato A, Jang K, Graceffa P, Tobacman LS, Li XE, Lehman W. Electron microscopy and persistence length analysis of semi-rigid smooth muscle tropomyosin strands. Biophys. J. 2010;99:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lehman W, Medlock G, Li XE, Suphamungmee W, Tu AY, Schmidtmann A, Ujfalusi Z, Fischer S, Moore JR, Geeves MA, Regnier M. Phosphorylation of Ser283 enhances the stiffness of the tropomyosin head-to-tail overlap domain. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2015;571:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Perz-Edwards RJ, Irving TC, Baumann BA, Gore D, Hutchinson DC, Kržič U, Porter RL, Ward AB, Reedy MK. X-ray diffraction evidence for myosin-troponin connections and tropomyosin movement during stretch activation of insect flight muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:120–125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014599107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smith DA, Maytum R, Geeves MA. Cooperative regulation of myosin-actin interactions by a continuous flexible chain I: Actin-tropomyosin systems. Biophys. J. 2003;84:3155–3167. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70040-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smith DA, Geeves MA. Cooperative regulation of myosin-actin interactions by a continuous flexible chain II: Actin-tropomyosin-troponin and regulation by calcium. Biophys. J. 2003;84:3168–3180. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70041-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mijailovich SM, Kayser-Herold O, Li X, Griffiths H, Geeves MA. Cooperative regulation of myosin-S1 binding to actin filaments by a continuous flexible Tm-Tn chain. Eur. Biophys. J. 2012;41:1015–1032. doi: 10.1007/s00249-012-0859-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Davis JP, Rall JA, Alionte C, Tikunova SB. Mutations of hydrophobic residues in the N-terminal domain of troponin C affect calcium binding and exchange with the troponin C-troponin I96-148 complex and muscle force production. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:17348–17360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314095200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kreutziger KL, Gillis TE, Davis JP, Tikunova SB, Regnier M. Influence of enhanced troponin C Ca2+-binding affinity on cooperative thin filament activation in rabbit skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2007;583:337–350. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.135426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kreutziger KL, Piroddi N, McMichael JT, Tesi C, Poggesi C, Regnier M. Calcium binding kinetics of troponin C strongly modulate cooperative activation and tension kinetics in cardiac muscle. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2011;50:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hofmann PA, Fuchs F. Evidence for a force-dependent component of calcium binding to cardiac troponin C. Am. J. Physiol. 1987;253:C541–C546. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.4.C541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Potter JD, Gergely J. Troponin, tropomyosin, and actin interactions in the Ca2+ regulation of muscle contraction. Biochemistry. 1974;13:2697–2703. doi: 10.1021/bi00710a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Monod J, Wyman J, Changeux J-P. On the nature of allosteric transitions: a plausible model. J. Mol. Biol. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Davis JP, Tikunova SB. Ca2+ exchange with troponin C and cardiac muscle dynamics. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008;77:619–626. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Perry SV, Troponin T. Genetics, properties and function. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motility. 1998;19:575–602. doi: 10.1023/a:1005397501968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Perry SV, Troponin I. Inhibitor or facilitator. Mol. Cell Biochem. 1999;190:9–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Perry SV. Vertebrate tropomyosin: Distribution, properties and function. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motility. 2001;22:5–49. doi: 10.1023/a:1010303732441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jin JP, Zhang Z, Bautista JA. Isoform diversity, regulation, and functional adaptation of troponin and calponin. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2008;18:93–124. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v18.i2.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sheng JJ, Jin JP. TNNI1, TNNI2 and TNNI3: Evolution, regulation, and protein structure-function relationships. Gene. 2016;576:385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sheehan KA, Arteaga GM, Hinken AC, Dias FA, Ribeiro C, Wieczorek DF, Solaro RJ, Wolska BM. Functional effects of a tropomyosin mutation linked to FHC contribute to maladaptation during acidosis. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2011;50:442–450. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hill TL, Eisenberg E, Greene L. Theoretical model for the cooperative equilibrium binding of myosin subfragment 1 to the actin-troponin-tropomyosin complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1980;77:3186–3190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hill TL, Eisenberg E, Greene LE. Alternate model for the cooperative equilibrium binding of myosin subfragment-1-nucleotide complex to actin-troponin-tropomyosin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1983;80:60–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rice JJ, de Tombe PP. Approaches to modeling crossbridges and calcium-dependent activation in cardiac muscle. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2004;85:179–195. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rice JJ, Stolovitzky G, Tu Y, de Tombe PP. Ising model of cardiac thin filament activation with nearest-neighbor cooperative interactions. Biophys. J. 2003;84:897–909. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74907-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Campbell SG, Lionetti FV, Campbell KS, McCulloch AD. Coupling of adjacent tropomyosins enhances cross-bridge-mediated cooperative activation in a markov model of the cardiac thin filament. Biophys. J. 2010;98:2254–2264. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Land S, Niederer SA. A spatially detailed model of isometric contraction based on competitive binding of troponin I explains cooperative interactions between tropomyosin and crossbridges. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015;11:e1004376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Aboelkassem Y, Bonilla JA, McCabe KJ, Campbell SG. Contributions of Ca2+-independent thin filament activation to cardiac muscle function. Biophys. J. 2015;109:2101–2112. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pirani A, Xu C, Hatch V, Craig R, Tobacman LS, Lehman W. Single particle analysis of relaxed and activated muscle thin filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;346:761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lehman W, Galińska-Rakoczy A, Hatch V, Tobacman LS, Craig R. Structural basis for the activation of muscle contraction by troponin and tropomyosin. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;388:673–681. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]