Abstract

Background

A permit to work (PTW) is a formal written system to control certain types of work which are identified as potentially hazardous. However, human error in PTW processes can lead to an accident.

Methods

This cross-sectional, descriptive study was conducted to estimate the probability of human errors in PTW processes in a chemical plant in Iran. In the first stage, through interviewing the personnel and studying the procedure in the plant, the PTW process was analyzed using the hierarchical task analysis technique. In doing so, PTW was considered as a goal and detailed tasks to achieve the goal were analyzed. In the next step, the standardized plant analysis risk-human (SPAR-H) reliability analysis method was applied for estimation of human error probability.

Results

The mean probability of human error in the PTW system was estimated to be 0.11. The highest probability of human error in the PTW process was related to flammable gas testing (50.7%).

Conclusion

The SPAR-H method applied in this study could analyze and quantify the potential human errors and extract the required measures for reducing the error probabilities in PTW system. Some suggestions to reduce the likelihood of errors, especially in the field of modifying the performance shaping factors and dependencies among tasks are provided.

Keywords: human error, standardized plant analysis risk-human, work permit system

1. Introduction

According to investigations on industrial accidents, human errors account for > 90% of accidents in nuclear industries, > 80% of accidents in chemical industries, > 75% of maritime accidents, and > 70% of aviation accidents [1]. Human error also constitutes one of the direct causes of some of the most shocking industrial accidents which have occurred around the world such as Bhopal in India (1984), Piper Alpha in the United Kingdom (1988), Chernobyl in Ukraine (1986), and Texaco Refinery in Wales (1994) [2].

In the worst industrial accident in world history, the Bhopal disaster, a combination of operator error, poor maintenance, failed safety systems, and poor safety management were identified as the causes of leaked methyl isocyanate gas from a pesticide plant which led to the creation of a dense toxic cloud and killed > 2,500 people. The explosion and fire accident which occurred in the Piper Alpha offshore oil and gas platform and killed 167 workers was attributed mainly to human error including deficiencies in the permit to work (PTW) system, deficient analysis of hazards, and inadequate training in the use of safety procedures. In the Chornobyl accident, operator error and operating instructions and design deficiencies were found to be the two main factors responsible for the explosion of a 1,000 MW reactor which released radioactive materials that spread over much of Europe. Finally, the main cause of the Texaco Refinery explosion, caused by continuously pumping inflammable hydrocarbon liquid into a process vessel which had a closed outlet, was the result of a combination of failures in management, equipment, and control systems, such as the inaccurate control system reading of a valve state, modifications which had not been fully assessed, failure to provide operators with the necessary process overviews, and attempts to keep the unit running when it should have been shut down [3].

Human error has been defined as any improper decision or behavior which may have a negative impact on the effectiveness, safety, or performance system [4]. A PTW is a formal written system to control certain types of works which are identified as potentially hazardous. This system may need to be used in high-risk jobs such as hot works, confined space entries, maintenance activities, carrying hazardous substances, and electrical or mechanical isolations [5]. In this system, responsible individuals should assess work procedures and check the safety at all stages of the work. Moreover, permits are effective means of communication among site managers, plant supervisors, and operators, and the individuals who carrying out the work. The people doing the job sign the permit to show that they understand the risks and the necessary precautions [6].

Although a PTW is an integral part of a safe system of work and can be helpful in the proper management of a wide range of activities, it may be susceptible to human error itself. For instance, a breakdown in the PTW system at shift change over and in the safety procedures was one of the major factors that resulted in the explosion and fire accident of the Piper Alpha oil and gas platform [7]. Also, the lack of an issued permit for the actual job was one of the reasons for the Hickson and Welch accident in 1992 [8].

Up to now, very limited studies have been conducted regarding human error analysis in the PTW system. Hoboubi et al [9] investigated the human error probabilities (HEPs) in a PTW using an engineering approach and estimated the HEP to range from 0.044 to 0.383. In another study conducted by the same authors [10], human errors in the PTW system were identified and analyzed using the predictive human error analysis technique. The most important identified errors in that study were inadequate isolation of process equipment, inadequate labeling of equipment, a delay in starting the work after issuing the work permit, improper gas testing, and inadequate site preparation measures. Moreover, findings of a study conducted by Haji Hosseini et al [11] on the evaluation of factors contributing to human error in the process of PTW issuing indicated a significant correlation between the errors and training, work experience, and age of the individuals involved in work permit issuance. However, as mentioned above, a limited number of researches have analyzed the PTW process from the human error point of view. Moreover, except for Hoboubi et al [9], other studies were descriptive in nature and failed to quantify the human errors in the PTW issuance process. In this context, the present study aimed to identify and analyze human errors in different steps of the PTW process in a chemical plant.

2. Material and methods

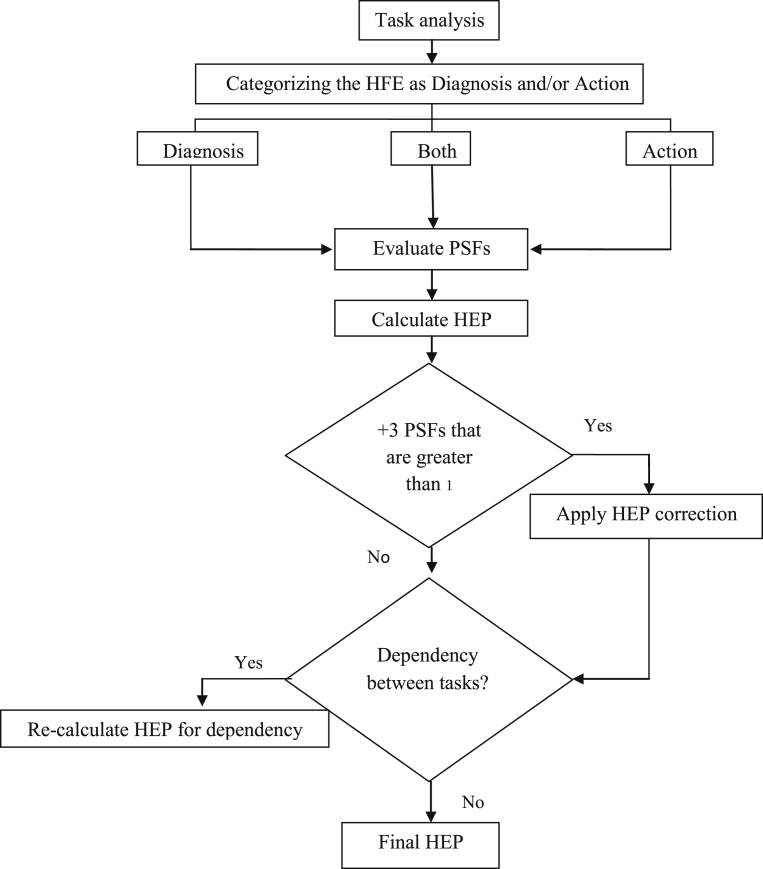

This cross-sectional, descriptive study was conducted to estimate the probability of human errors in a PTW system in an Iranian chemical plant. In the first stage, through interviewing the personnel and studying the procedures of various tasks in the plant, the PTW process was analyzed by the hierarchical task analysis (HTA) technique. In doing so, PTW was considered as a goal and detailed tasks to achieve the goal were analyzed. In the next step, the standardized plant analysis risk-human (SPAR-H) reliability analysis method, developed by the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission, was applied for estimation of HEP [12]. Although the SPAR-H technique was originally developed in the nuclear power industry and its application for the estimation of HEPs in outside process and safety control tasks like those found in other industries (such as the petrochemical industry) may be controversial in terms of type and complexity of the tasks, physical and cognitive demands of the tasks, and physical and mental requirements to the operators, it has recently been used for human reliability analysis (Fig. 1.) in major accident risk analyses in the Norwegian petroleum industry, offshore drilling operations in the oil and gas industry, and managed-pressure drilling operations [13], [14].

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the human reliability assessment using the SPAR-H technique. HEP, human error probability; HFE, human failure event; PSFs, performance shaping factors; SPAR-H, standardized plant analysis risk-human.

The SPAR-H is a structural HRA technique used to identify and calculate the probability of potential human error in the described occupational tasks (human failure events-HFEs). It is based on a basic nominal error rate, a set of performance shaping factors (factors that affect human error), and the error dependency between tasks.

According to Whaley et al [15], the steps for using the SPAR-H in human reliability analysis in PTW in the studied petrochemical plant of the current research were as follows. (1) Categorizing the HFE as diagnosis and/or action. In the first step, identified HFEs in the PTW tasks were categorized as either diagnosis tasks (cognitive processing) or action tasks (execution) or combined diagnosis and action. (2) Evaluating and rating the performance shaping factors (PSFs). In this stage, all of the HFEs were evaluated based on eight PSFs, including available time, stress/stressor, complexity, experience/training, procedure, ergonomics/human-machine interface (HMI), fitness for duty, and work process. The level of each PSF was determined based on the SPAR-H procedure (Table 1). Therefore, each PSF was examined and rated with respect to the context of the HFE. For this purpose, operators involved in the PTW procedure were interviewed and monitored during the PTW issuing activities. Then, the corresponding levels of PSFs were selected from the PSFs table based on the SPAR-H procedure (Table 2) [12]. If there was not enough information available to provide an informed judgment, the PSF was assumed to be nominal. (3) Calculating PSF-modified HEP. Once the PSF levels have been assigned, then the final HEP was simply the product of the basic HEP and the PSF multipliers [Eq. (1)].

| (1) |

Table 1.

Rated PSFs and calculated PSFc in permit to work tasks in the studied petrochemical plant

| Task/subtask | Operator | PSF |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Available Time (i1) | Stress/stressors (i2) | Complexity (i3) | Experience/ Training (i4) | Procedure (i5) | Ergonomics (i6) | Fitness for duty (i7) | Work processes (i8) | PSFc = ΠPSFs | |||

| 1. Site inspection | Shift supervisor | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | |

| 2. Description of hot/cold work | Shift supervisor | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | |

| 3. Site preparation | |||||||||||

| 3.1. Venting process equipment from flammable & toxic materials | Site Man 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 30 | |

| Site Man 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||

| 3.2. Lock out & tag out the electrical equipment | Site Man 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15 | |

| Site Man 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| 3.3. Cleaning the work area from flammable material | Site Man 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15 | |

| Site Man 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| 3.4. Isolation of process equipment | Site Man 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 60 | |

| Site Man 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||

| 4. Flammable gas testing | Site Man 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15 | |

| Site Man 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| 5. Oxygen & toxic gas testing | Safety Officer | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | |

| 6. Specify the protective devices on the permit | Shift Supervisor | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.8 | 8 | |

| 7. Specify safety measures on the permit | Shift Supervisor | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.8 | 8 | |

| 8. Show work area to operator | Site Man 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 30 | |

| Site Man 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||

| 9. Site inspection by shift supervisor | Shift Supervisor | 10 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |

| 10. Signing the permit | Shift Supervisor | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | |

| 11. Validation & revalidation after shift handover | Shift Supervisor | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | |

PSF, performance shaping factor; PSFc, the composite PSF.

Table 2.

A sample of the SPAR-H worksheet for PSF evaluation in “flammable gas testing” task conducted by site men

| Action portion |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| PSF | PSF level | Multiplier for action Site Man 1 |

Multiplier for action Site Man 2 |

| Available time | Inadequate time | p (failure) = 1 | p (failure) = 1 |

| Time available is ∼ the time required | 10 | 10 | |

| Nominal time | 1 | 1 | |

| Time available is ≥ 5× the time required | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Time available ≥ 50× the time required | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| Stress/stressors | Extreme | 5 | 5 |

| High | 2 | 2 | |

| Nominal | 1 | 1 | |

| Insufficient information | 1 | 1 | |

| Complexity | Highly complex | 5 | 5 |

| Moderately complex | 2 | 2 | |

| Nominal | 1 | 1 | |

| Insufficient information | 1 | 1 | |

| Experience/Training | Low | 3 | 3 |

| Nominal | 1 | 1 | |

| High | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| Insufficient Information | 1 | 1 | |

| Procedure | Not available | 50 | 50 |

| Incomplete | 20 | 20 | |

| Available, but poor | 5 | 5 | |

| Nominal | 1 | 1 | |

| Insufficient information | 1 | 1 | |

| Ergonomics | Missing/misleading | 50 | 50 |

| Poor | 10 | 10 | |

| Nominal | 1 | 1 | |

| Good | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| Insufficient information | 1 | 1 | |

| Fitness for duty | Unfit | p (failure) = 1 | p (failure) = 1 |

| Degrade fitness | 5 | 5 | |

| Nominal | 1 | 1 | |

| Insufficient information | 1 | 1 | |

| Work processes | Poor | 5 | 5 |

| Nominal | 1 | 1 | |

| Good | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| Insufficient information | 1 | 1 | |

| ΠPSF = 15 | ΠPSF = 5 | ||

PSF, performance shaping factor; SPAR-H, standardized plant analysis risk-human.

Note: Gray color shows the selected PSFs level.

When diagnosis and action were combined into a single HFE, the two HEPs were calculated separately and then summed to produce the composite HEP. For tasks with at least three negative PSFs (based on PSF levels), HEP was calculated using Eq. (2).

| (2) |

In Eqs. (1) and (2), PSFc is the composite PSF (PSF multipliers) and NHEP is the nominal HEP. According to the SPAR-H methodology, NHEPs for action and diagnostic activities were considered as 0.001 and 0.01, respectively [12]. These nominal SPAR-H HEP values are based on error rates for simple action implementation (such as pressing a button or turning a dial, and simple slips or lapses) and cognitive processing in diagnosis activities [15], [16]. (4) Calculating final HEP for dependent and independent tasks. Eq. (3) was used to compute the HEP for independent tasks.

| (3) |

where PW/OD = HEP for independent tasks, HEPD = HEP for diagnostic activities, and HEPA = HEP for action activities). With respect to the dependent tasks, the role of dependency among the PTW tasks was corrected. In doing so, dependency level (complete, high, moderate, low, and zero) was determined based on the location of doing the tasks (same or different), cause (additional or not additional), time (close in time or not), and crew (same or different) using the dependency table in the SPAR-H procedure and consequently the final HEP was calculated (Table 3) [12].

Table 3.

A sample of the SPAR-H worksheet for dependency determination in “flammable gas testing” task

| Condition number | Crew (some or different) | Time (close in time or not close in time) | Location (some or different) | Cause (additional or not additional) | Dependency | HEP calculation formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | s | c | s | na | Complete | The probability of failure is 1 |

| 2 | a | Complete | ||||

| 3 | d | na | High | (1 + PW/OD)/2 | ||

| 4 | a | High | ||||

| 5 | nc | s | na | High | ||

| 6 | a | Moderate | (1 + 6 × PW/OD)/7 | |||

| 7 | d | na | Moderate | |||

| 8 | a | Low | (1 + 19 × PW/OD)/20 | |||

| 9 | d | c | s | na | Moderate | (1 + 6 × PW/OD)/7 |

| 10 | a | Moderate | ||||

| 11 | d | na | Moderate | |||

| 12 | a | Moderate | ||||

| 13 | nc | s | na | Low | (1 + 19 × PW/OD)/20 | |

| 14 | a | Low | ||||

| 15 | d | na | Low | |||

| 16 | A | Low | ||||

| 17 | Zero | The probability of failure is PW/OD |

a, additional; c, close in time; d, different; HEP, human error probability; na, not additional; nc, not close in time; PW/OD, probability without dependency; s, same; SPAR-H, standardized plant analysis risk-human.

Note: Gray color shows the selected dependency level and its corresponding formula for HEP calculation.

3. Results

The PTW process in the studied plant involved four operators including two site men: Site Man 1 (28 years old with 6 months working experience) and Site Man 2 (26 years old with 2 years working experience), one shift supervisor (39 years old with 12 years working experience), and one safety officer (29 years old with 5 years working experience).

The results of HTA in PTW tasks are presented in Table 1. As the table depicts, the PTW procedure consisted of 11 main tasks and four subtasks. Table 1 also presents the level of PSFs and calculated PSFc in each task of the PTW process for all the operators involved.

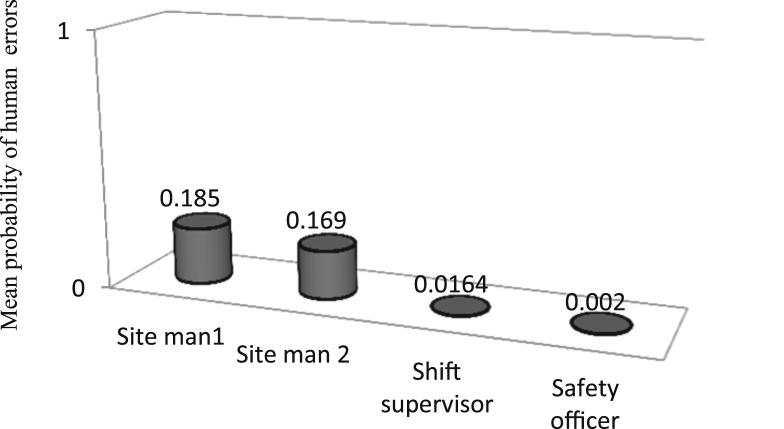

Table 4 presents the values of HEPD, HEPA, HEPWO/D, HEPW/D, and total HEP for each task in the PTW process. Accordingly, the mean HEP in the PTW process was 0.112. In addition, the highest probability of human error related to flammable gas testing. The comparison of HEP among different occupational groups involved in the PTW procedure has been presented in Fig. 2. According to this figure, among the individuals involved in the PTW process, site men had the highest probability of human errors. A sample of the SPAR-H worksheet used for the evaluation of PSFs and determination of dependency in the “flammable gas testing” task have been shown in Table 2, Table 3, respectively.

Table 4.

Human error probability in a permit to work process in the studied chemical plant

| Task/subtask | Operator | PSFC | HEPD | HEPA | PW/OD | PW/D | Final HEP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Site inspection | Shift Supervisor | 10 | – | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| 2. Description of hot/cold work | Shift Supervisor | 10 | – | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| 3. Site preparation | ||||||||

| 3.1. Venting process equipment from flammable & toxic materials | Site Man 1 | 30 | – | 0.029 | 0.029 | 0.168 | 0.168 | |

| Site Man 2 | 10 | – | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.151 | 0.151 | ||

| 3.2. Lock out & tag out the electrical equipment | Site Man 1 | 15 | – | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.156 | 0.156 | |

| Site Man 2 | 5 | – | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.147 | 0.147 | ||

| 3.3. Cleaning the work area from flammable material | Site Man 1 | 15 | – | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.064 | 0.064 | |

| Site Man 2 | 5 | – | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.055 | 0.055 | ||

| 3.4. Isolation of process equipment | Site Man 1 | 60 | – | 0.056 | 0.056 | 0.191 | 0.191 | |

| Site Man 2 | 10 | – | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.151 | 0.151 | ||

| 4. Flammable gas testing | Site Man 1 | 15 | – | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.507 | 0.507 | |

| Site Man 2 | 5 | – | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.502 | 0.502 | ||

| 5. Oxygen & toxic gas testing | Safety Officer | 0.25 | – | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | |

| 6. Specify the protective devices in the permit | Shift Supervisor | 8 | 0.04 | – | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| 7. Specify safety measures in the permit | Shift Supervisor | 8 | 0.04 | – | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| 8. Showing work area to operator | Site Man 1 | 30 | – | 0.029 | 0.029 | 0.029 | 0.029 | |

| Site Man 2 | 10 | – | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| 9. Site inspection by shift control | Shift Supervisor | 5 | – | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | |

| 10. Signing the permit | Shift Supervisor | 0.5 | 0.005 | – | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | |

| 11. Validation & revalidation after shift handover | Shift Supervisor | 0.5 | 0.005 | – | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | |

| PSFc | 12.61 | 0.112 | ||||||

HEP, human error probability; HEPA, human error probability in action tasks; HEPD, human error probability in diagnostics tasks; PSF, performance shaping factor; PSFc, the composite PSF; PW/D, probability with dependency; PW/OD, probability without dependency.

Fig. 2.

The mean probability of human errors in the operators involved in the work permit system in the studied chemical plant.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to estimate the probability of human errors in the PTW procedure using the SPAR-H technique. The results showed the mean probability of human error in the PTW system to be 0.112. Additionally, the highest probability of human error in the PTW process was related to “flammable gas testing” (0.507).

The results of the current study also revealed that the probability of human error was higher in the tasks performed by site men when compared with other occupational groups involved in the PTW procedure. Besides this, the highest probability of human error was related to Site Man 1 (0.507) and Site Man 2 (0.502) in the “flammable gas testing” task, which could be attributed to unsuitability of the PSF level (low experience and training and poor procedure) in site men compared to other groups. Considering the knowledge-based nature of the flammable gas testing task [9], low education and experience levels may reduce the operators' technical skills and increase the probability of knowledge-based errors [17]. This finding is consistent with the findings of the current study conducted on the PTW process [9].

Due to the appropriate level of PSFs and the low level of dependency, HEP was lower in the tasks performed by the shift supervisor when compared with other tasks. Among the tasks carried out by the shift supervisor, the highest probability of human error was related to “specifying the required personal protection equipment” and “determining precautions in the permit” tasks, which is due to the diagnostic nature of these tasks.

In the only task conducted by the safety officer, HEP was computed as 0.002 which is the minimum probability among all the tasks in the PTW process. This resulted from the fact that the safety officer had the most appropriate PSFs level.

The HEP values obtained in the present study were higher when compared with those reported in previous work [9]. This difference in error probability can be explained by differences between the types of techniques used for human error assessment and the fields studied. The highest human error values in both studies were related to “flammable gas testing” tasks.

According to the PTW procedure in the studied chemical plant, site men were responsible for both “isolation of process equipment” and “flammable gas testing” tasks. Furthermore, there was no appropriate specific procedure for gas testing in the studied plant. Based on the SPAR-H methodology, this led to a high dependency level and caused the error probabilities of 0.507 and 0.502 for Site Men 1 and 2 respectively in the gas testing task. By employing a qualified person for gas testing (except site men) as well as by providing an appropriate procedure, the level of dependency can be reduced. In this way, the final HEP of this task would reduce to 0.064 for Site Man 1 and to 0.054 for Site Man 2, which is 8–9 times lower.

In the present study, the estimated HEPs for the “flammable gas testing” task was unexpectedly high (0.5). This indicated the high level of dependency in this task (Table 3). According to the SPAR-H methodology, for the tasks with high dependency levels, HEP is at least 0.5, even if all PSFs are at appropriate levels.

One of the limitations of the present study was that it only measured HEP in the general procedure of the PTW system in the studied plant. Therefore, the findings might not be generalized to all PTW procedures and a work permit for any specific work should be studied for potential human errors. Moreover, SPAR-H is a technique developed for the nuclear industry and may not be fully applicable to all situations in process industries. Therefore, more studies are necessary to customize and validate the PSFs for work situations in petrochemical industries.

In conclusion, the SPAR-H method applied in this study could be used to analyze and quantify potential human errors and extract the required measures necessary to reduce error probabilities in a PTW system. Based on the results, the following suggestions are provided to reduce the likelihood of errors: (1) employing a qualified person for gas testing (except site men). In this way, the dependency level of tasks conducted by site men will be reduced; (2) providing a specific appropriate procedure for the task of “flammable gas testing”; (3) revising the PTW procedure for detailed explanation of responsibilities of all the operators involved in PTW issuance and its related work activities; and (4) as a simple and appropriate solution, the automation of the PTW issuance procedure can be very effective in preventing and reducing the probability of human errors.

Conflicts of interest

All contributing authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This article was extracted from the thesis written by Naser Hoboubi, an M.Sc. student of Occupational Health Engineering and was financially supported by the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (Grant No. 93–7086). The authors would like to thank Ms A. Keivanshekouh at the Research Improvement Center of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for her assistance with the use of the English language in the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Mehdi Jahangiri, Email: jahangiri_m@sums.ac.ir.

Naser Hoboubi, Email: hobobinaser@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.De Felice F., Petrillo A., Carlomusto A., Ramondo A. Human reliability analysis: a review of the state of the art. IRACST – Int J Res Manage Technol (IJRMT) 2012;2:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson C. Why human error modeling has failed to help systems development. Interact Comput. 1999;11:517–524. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Disaster Management Institute . 2010. Human factors vs accident causation industrial disaster risk management (Theme-7) [Internet]. Bhopal (India)www.hrdp-idrm.in/e5783/e17327/e28899/e28897/Theme-7CDR-11-11-fb.pdf [cited 2015 Jul 9]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kletz T.A. IChemE, Third edition CRC Press Book; 2001. An engineer's view of human error. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Health and Safety Executive (HSE). Permit to work systems guidance England [Internet]. HSE Book. 2014 [cited 2015 Jul 9]. Available from: http://www.hse.gov.uk/comah/sragtech/techmeaspermit.htm.

- 6.Health and Safety Executive (HSE) 2015. Human factors: permit to work systems England [Internet] [cited 2015 Jul 9]. Available from: http://www.hse.gov.uk/humanfactors/topics/ptw.htm, London, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paté-Cornell M.E. Learning from the piper alpha accident: A postmortem analysis of technical and organizational factors. Risk Anal. 1993;13:215–232. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Health and Safety Executive (HSE). Guidance on permit-to-work systems [Internet]. A guide for the petroleum, chemical and allied industries England. HSE Book. 2005 [cited 2015 Jul 9]. Available from: http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/books/hsg250.htm.

- 9.Hoboubi N., Jahangiri M., Keshavarzi S. Quantitative human error assessment using engineering approach in permit to work system in a petrochemical plant. Iran Occup Health. 2014;11:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jahangiri M., Derisi F.Z., Hoboubi N. CRC Press; Boca Raton (FL): 2014. Predictive human error analysis in permit to work system in a petrochemical plant. Safety and reliability: Methodology and applications; pp. 1007–1010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hosseini A.H., Jafari M., Mehrabi Y., Halwani G., Ahmadi A. Factors influencing human errors during work permit issuance by the electric power transmission network operators. Indian J Sci Technol. 2012;5:3169–3173. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gertman D.I., Blackman H.S., Marble J., Byers J., Smith C. Idaho National Laboratory Idaho Falls (ID); 2005. The SPAR-H human reliability analysis method. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gould K.S., Ringstad A.J., van de Merwe K., editors. Human reliability analysis in major accident risk analyses in the Norwegian petroleum industry. Sage Publications; London (UK): 2012. (Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting). [Google Scholar]

- 14.van de Merwe K., Øie S., Gould K., editors. The application of the SPAR-H method in managed-pressure drilling operations. Sage Publications; London (UK): 2012. (Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whaley A.M., Kelly D.L., Boring R.L., Galyean W.J. Risk, Reliability, and NRC Programs Department, Idaho National Laboratory; Idaho Falls (ID): 2011. SPAR-H step-by-step guidance. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boring R.L., Blackman H.S., editors. The origins of the SPAR-H method's performance shaping factor multipliers. IEEE; Monterey (CA): 2007. (Human Factors and Power Plants and HPRCT 13th Annual Meeting, 2007 IEEE 8th). [CO18] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haji Hoseini A. 2011. Prediction and reduction of human errors in operators of control rooms in Yazd regional electric power supply & distribution co, using SHERPA. A dissertation thesis for the fulfillment of the M.Sc. degree in Occupational Health Engineering, University of Shahid Beheshti (MC). Tehran (Iran) [in Persian] [Google Scholar]