Abstract

Targeting nanocarriers (NC to endothelial cell adhesion molecules including Platelet-Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (PECAM-1 or CD31) improves drug delivery and pharmacotherapy of inflammation, oxidative stress, thrombosis and ischemia in animal models. Recent studies unveiled that hydrodynamic conditions modulate endothelial endocytosis of NC targeted to PECAM-1, but the specificity and mechanism of effects of flow remain unknown. Here we studied the effect of flow on endocytosis by human endothelial cells of NC targeted by monoclonal antibodies Ab62 and Ab37 to distinct epitopes on the distal extracellular domain of PECAM. Flow in the range of 1 – 8 dyne/cm2, typical for venous vasculature, stimulated the uptake of spherical Ab/NC (~180 nm diameter) carrying ~50 vs 200 Ab62 and Ab37 per NC, respectively. Effect of flow was inhibited by disruption of cholesterol-rich plasmalemma domains and deletion of PECAM-1 cytosolic tail. Flow stimulated endocytosis of Ab62/NC and Ab37/NC via eliciting distinct signaling pathways mediated by RhoA/ROCK and Src Family Kinases, respectively. Therefore, flow stimulates endothelial endocytosis of Ab/NC in a PECAM-1 epitope specific manner. Using ligands of binding to distinct epitopes on the same target molecule may enable fine-tuning of intracellular delivery based on the hemodynamic conditions in the vascular area of interest.

Keywords: Intracellular delivery, endothelial cells, vascular immunotargeting, cell adhesion molecules, endocytosis, fluid shear stress

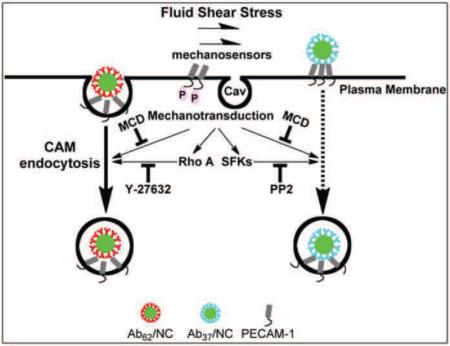

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Cellular uptake of targeted nanocarriers (NC) for drug delivery is regulated by parameters of carrier design (e.g., selection of target epitopes), as well as target cell phenotype and factors associated with the cellular microenvironment [1–4]. Thus, experimental models for delivery of NC should account for target cell conditions in vivo [5–8]. For example, the functional status of endothelial cells lining the vascular lumen, an important target for drug delivery, is greatly influenced by fluid shear stress of blood flow that varies under physiological and pathological conditions [9]. The role of blood rheology and hydrodynamics in NC binding to endothelium is extensively studied [10–15]. In contrast, relatively little is known about the role of these factors in the intracellular uptake of nanoparticles bound to specific endothelial surface molecules. Several lines of evidence suggest an important role of flow in the regulation of endocytosis of macromolecules and particles, such as albumin, non-targeted nanoparticles (e.g., quantum dots, SiO2− nanoparticles [16]), and nano- and micro-sized hydrogel spheres [17].

However, the role of hemodynamics in endocytosis of NC targeted to endothelial cells by affinity ligands including antibodies (i.e., Ab/NC) remains enigmatic. It is plausible that flow regulates this process in a ligand-specific fashion, since nature of the binding site and mode of ligand engagement control the mechanism of endocytosis. Recent studies in vitro and in vivo revealed that flow conditions modulate endothelial endocytosis of Ab/NC targeted to the cell adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and PECAM-1 [12,18]. Drug delivery using Ab/NC targeted to these determinants improves therapeutic effects of experimental drugs and biotherapeutics in animal models [19–22]. This justifies efforts directed towards extending our knowledge of the factors controlling intracellular delivery of NC targeted to these molecules. PECAM-1 antibodies bind to endothelial cells but do not accumulate significantly in the intracellular compartments [23,24]. In contrast, the multivalent binding of NCs coated with PECAM-1 antibody (e.g., Ab/NC) leads to intracellular uptake mediated by the pathway known as CAM-endocytosis, distinct from clathrin- or caveolae-mediated endocytosis, phagocytosis and macropinocytosis [23,25]. Furthermore, recent studies showed that shear stress stimulates endocytosis of PECAM-1-targeted Ab/NC [18].

However, previous studies revealed that under standard static cell culture conditions, human endothelial cells differentially internalize Ab/NC targeted to specific PECAM-1 epitopes: e.g., they internalize Ab/NC targeted by monoclonal antibody 62 (Ab62) but not by monoclonal antibody 37 (Ab37), which both are directed to distinct epitopes located in the distal Ig-like domain of PECAM-1 (i.e., Ab62/NC and Ab37/NC, respectively) [26]. These findings imply that control of endothelial internalization by physiological factors including flow may be different for Ab/NC targeted to distinct epitopes of PECAM-1. In the present study we have investigated whether this effect of flow is epitope-specific.

RESULTS

Flow differently modulates endothelial internalization of Ab/NC targeted to distinct PECAM-1 epitopes

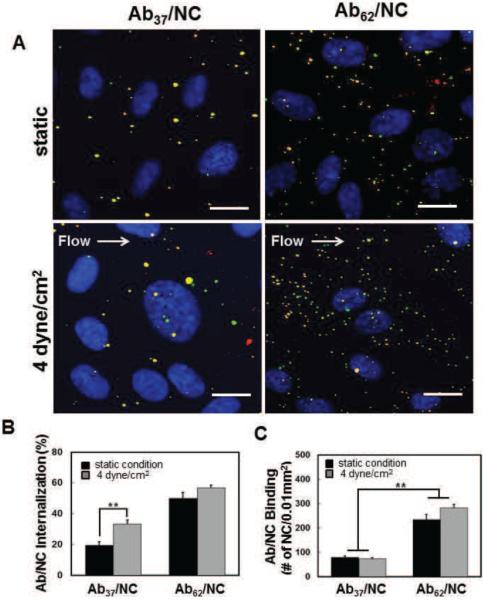

Binding to and uptake by target cells are proportional to Ab/NC's avidity, controlled by antibody affinity and number on a NC surface. Coupling ~200 antibody molecules per 100 nm particle provides nearly maximal surface density of monolayer IgG coating [27]. We started with assessing the uptake by endothelial cells of such NC coated by Ab37 vs Ab62, either at static conditions or 30 minutes after exposure to non-pulsatile laminar flow generating a flow shear stress of 4 dyne/cm2. Double-label fluorescent microscopy with secondary fluorescent antibody allows to distinguish cell surface-bound vs intracellular fluorescent nanocarriers (Fig.1A). We found that flow almost doubles uptake of Ab37/NC, which are barely internalized by static endothelial cells (Fig. 1A & B). However, flow rather trivially augmented uptake of Ab62/NC, which are effectively internalized by static cells (Fig. 1A & B).

Figure 1. Endothelial binding and internalization of nanocarriers coated by Ab37 and Ab62.

A, Representative fluorescence images showing endothelial binding (total particles) and internalization (green particles) of NC coated with Ab37 (left panel) versus Ab62 (right panel) at maximal Ab density on the surface of NC (200Abs/NC) under static and laminar flow conditions. Scale bar is 20 μm. B and C, confluent endothelial cells were incubated or exposed to flow (4 dyne/cm2) with Ab/NC at the NC concentration of 2 ×109/ml for 30 min at 37 °C. Flow stimulates internalization of Ab37/NC (B). Fewer Ab37/NC were bound to endothelial cells under static and flow conditions (C). The percentage of Ab/NC internalized into endothelial cells (B) and total number of Ab/NC bound to endothelial cells (C) in each image field (0.01mm2) were quantified by fluorescence microscopy and presented as Mean ± S.E. (n = 8). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

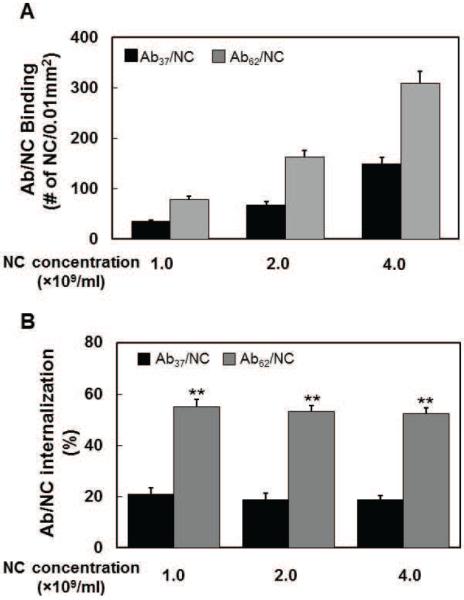

The binding of Ab37/NC to endothelial cells was markedly lower than that of Ab62/NC (Supplemental table 2 and Fig.1A and C). Noteworthy, flow stimulated internalization of Ab37/NC without changing its binding (Fig.1B and C). The data of uptake of Ab/NC incubated at different concentrations with static cells further distinguished binding vs internalization. As expected, endothelial binding of both types of Ab/NC increased proportionally to their concentration (Fig.2A). Importantly, binding of Ab37/NC at high concentration exceeded that of Ab62/NC at low concentration. However, the level of Ab37/NC internalization remained consistently three-fold lower than that of Ab62/NC, i.e., ~20% vs 60% (Fig.2B). Taken together, these data indicate that both Ab/NC internalization and its modulation by flow do not necessarily correlate directly with number of cell-bound Ab/NC. This is important in the context of the effects of flow in endocytosis of Ab/NC (see Discussion).

Figure 2. Endocytosis of Ab37/NC and Ab62/NC is independent of the total number of Ab/NC bound to endothelial cells.

A, Ab37/NC and Ab62NC (200 Ab/NC) at different concentration (1, 2, and 4 × 109 particles/ml) were incubated with confluent endothelial cells for 30 minutes. The total number of Ab37/NC (black bar) and Ab62/NC (gray bar) bound to cells and their internalization (insert) in each image field (0.01mm2) were quantified by fluorescence microscopy.

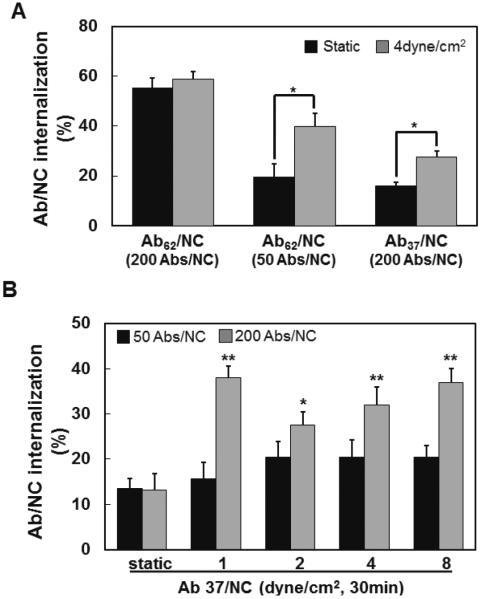

However, antibody surface density, which controls valence and avidity of binding, is an important factor in flow-mediated stimulation of the Ab/NC uptake. First, reduction of surface density of Ab62/NC coating from ~200 to 50 antibody molecules per particle decreased endothelial endocytosis to the level comparable with that of Ab37/NC carrying ~200 antibody molecules (Fig.3A). Second, flow stimulated endocytosis of Ab62/NC with low Ab density similarly to that of Ab37/NC with high Ab density. Finally, flow ranging from 1 to 8 dyne/cm2 showed a trend to stimulate proportionally endocytosis of Ab37/NC carrying ~50 Ab molecules, but this trend did not reach statistical significance (Fig.3B).

Figure 3. Fluid shear stress stimulates endocytosis of Ab37/NC and Ab62/NC: role of Ab/NC avidity.

A, internalization of Ab62/NC (50 and 200 Abs/NC) and Ab37/NC (200 Abs/NC) under static and flow conditions (incubation or perfusion at 4 dyne/cm2 for 30 minutes) were quantified. B, internalization of Ab37/NC at low (50 Abs/NC) and high (200 Abs/NC) antibody density over particle surface in endothelial cells was quantified under static or flow (1, 2, 4, 8 dyne/cm2, 30 minutes) conditions *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 in comparison with static groups.

These data show that flow stimulates endocytosis of Ab/NC within a restricted range of Ab/NC avidity to endothelium. For Ab62/NC and Ab37/NC, it is close to that provided by low and high antibody density, respectively. Exceeding this empirical range, e.g., by using high antibody density Ab62/NC results in a high internalization rate overshadowing the effect of flow, whereas falling below this range (e.g., by using low Ab density Ab37/NC) inhibits the internalization beyond that which is salvageable by stimulatory flow effect.

Cholesterol-rich plasmalemma domain(s) and PECAM-1 cytosolic tail mediate stimulation of endocytosis of Ab62/NC and Ab37/NC by flow

Next, we addressed cellular mechanisms involved in stimulation of endocytosis by flow. Here we focused on two factors: sensing of flow by cholesterol-rich domains in the plasmalemma and signaling via PECAM-1 anchoring molecule.

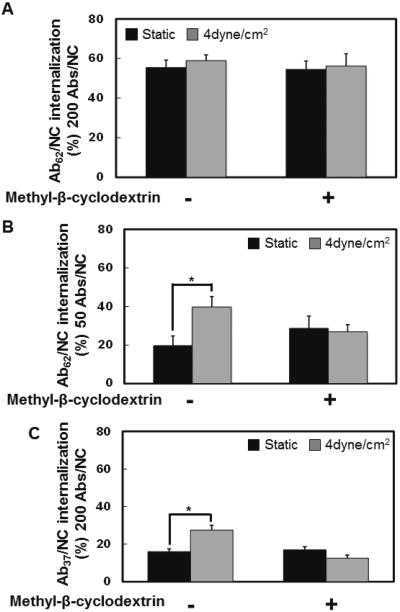

First, we found that cholesterol sequestration by methyl-β-cyclodextrin, which affects the lipid rafts and caveolae, abrogated stimulatory effect of flow on endothelial endocytosis of Ab37/NC and Ab62/NC (high and low antibody density formulations, respectively), without affecting their internalization under static conditions (Fig.4).

Figure 4. Disruption of lipid rafts abolished the shear stress-stimulated endocytosis of Ab37/NC and Ab62/NC.

Methyl-β-cyclodextrin pretreatment inhibited shear stress (4 dyne/cm2)-induced endocytosis of Ab62/NC (200 Abs/NC, A), (50 Abs/NC, B) and Ab37/NC (200 Abs/NC, C). Confluent endothelial cells were pre-treated with Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (1mM) for 30 minutes, followed by incubation or perfusion of Ab/NC for 30 minutes in the presence of Methyl-β-cyclodextrin. Internalization of Ab/NC was analyzed and expressed as Mean ± S.E. (n = 6, *p < 0.05, in comparison with static groups).

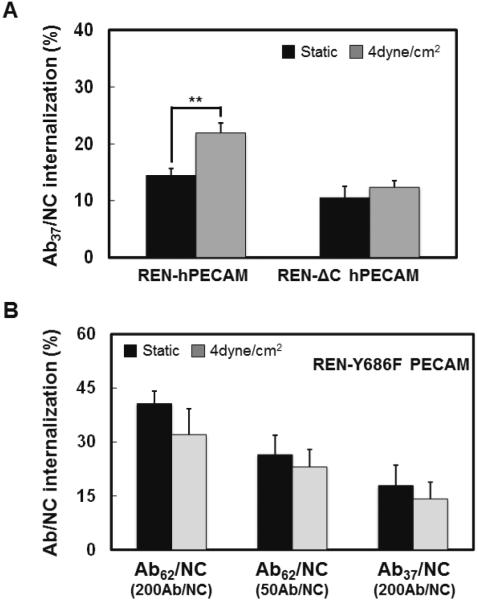

Second, we tested whether signaling via PECAM-1 intracellular domain is involved in flow-stimulated endocytosis of Ab/NC. We employed REN cells (which are naturally PECAM-1 null) transfected with full-length PECAM-1 vs mutant PECAM-1 lacking the cytosolic domain, as described in our previous work [18]. The results shown in Fig.5A indicate that: i) flow does stimulate uptake of Ab37/NC by non-endothelial REN cells expressing full-length PECAM-1, which is similar to our observation in endothelial cells and thus validates this model; and, ii) deletion of PECAM-1 cytosolic domain abrogates this effect of flow. Further, flow did not enhance endocytosis of either Ab62/NC or Ab37/NC (50 and 200 Ab per NC, respectively) in REN cells expressing phosphorylation deficiency mutant (Y686F) of PECAM-1 (Fig.5B). Therefore, flow stimulates Ab/NC endocytosis via signaling pathway(s) involving cholesterol-rich domains of plasmalemma and Tyr686 in cytosolic tail of PECAM-1.

Figure 5. Phosphorylation of PECAM-1 cytoplasmic domain is required for fluid shear stress-stimulated endocytosis of Ab/NC.

A, Cytoplasmic domain of PECAM-1 mediated the stimulatory effect of flow (4 dyn/cm2, 30 minutes) on endocytosis of Ab37/NC. B, Expression of phospho-defective PECAM-1 mutant Y686F inhibited flow-stimulated endocytosis of Ab37/NC (200 Ab/NC) and Ab62/NC (50 Ab/NC). REN cells stably expressing human PECAM-1 WT and cytoplasmic domain deleted mutant ΔCD (A), or phosphor-defective mutant Y686F (B) were incubated or perfused with Ab37/NC for 30 minutes at 37 °C. Internalization of Ab37/NC and Ab62/NC was analyzed and expressed as Mean ± S.E. (n = 6, **p < 0.01)

Stimulation of endothelial uptake of Ab62/NC and Ab37/NC by flow involves different intracellular signaling pathways

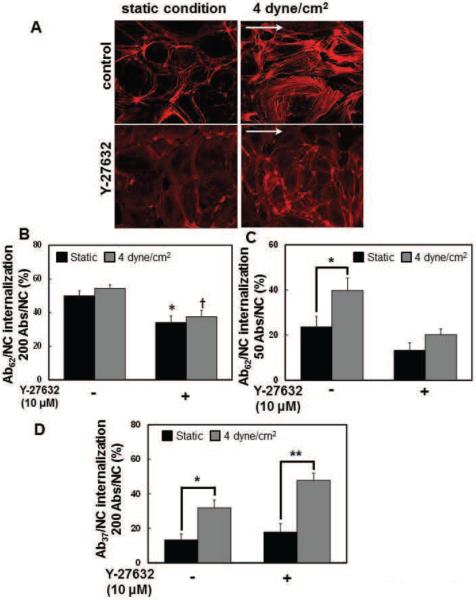

We addressed the role of RhoA/ROCK signaling pathway(s) and actin cytoskeleton rearrangements in modulation of Ab/NC internalization by flow. Treatment of endothelial cells with Y-27632, a pharmacological agent that inhibits RhoA/ROCK, decreased polymerized actin bundles in endothelial cells under static conditions, and prevented rearrangement of the endothelial actin cytoskeleton in response to flow (Fig.6A), in accord with the literature establishing the pivotal role of RhoA/ROCK signaling in dynamic regulation of cytoskeleton in endothelial cells. Based on this, we examined the role of this signaling in regulation of endocytosis of Ab/NC by flow. We found that inhibition of RhoA/ROCK by Y-27632: i) suppressed internalization of high-avidity Ab62/NC (200 Abs/NC) under both static and flow conditions (Fig.6B); ii) abrogated flow-induced stimulation of uptake of low avidity Ab62/NC (50 Abs/NC, Fig.6C); and, iii) in stark contrast, did not affect the stimulatory effect of flow on Ab37/NC uptake (Fig.6D). This result suggests that flow stimulates endocytosis of Ab62/NC and Ab37/NC via different signaling mechanisms.

Figure 6. Blockage of RhoA/ROCK signaling pathway specifically inhibits shear stress-induced endocytosis of Ab62/NC.

A, Y-27632, a Rho-kinase inhibitor, prevented cytoskeletal remodeling in response to flow dependent shear stress. Confluent endothelial cells were incubated or perfused at a flow of 4dyne/cm2 with culture medium in the absence or presence of Y-27632 (10 μM) for 30 minutes. Cells were then fixed and stained for F-actin using Alexa-Fluor594-phalloidin. Images were taken using fluorescence microscope with a Plan Apo 40× oil objective. Arrows show direction of flow. B and C, pretreatment of endothelial cells with Y-27632 (10 μM, 30 minutes) diminished the endocytosis of Ab62/NC (200 Abs/NC (A), 50 Abs/NC (B)) under both static and flow conditions. D, Y-27632 pretreatment did not inhibit shear stress-stimulated endocytosis of Ab37/NC (200 Abs/NC). *,† p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 in comparison with static groups.

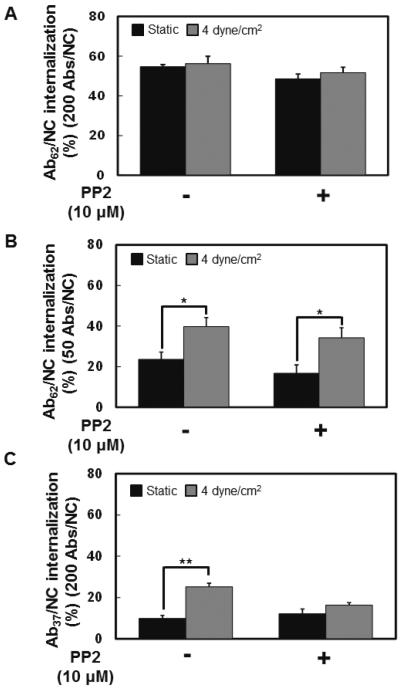

Finally, we tested the role of Src-family kinases (SFK). In a sharp contrast to RhoA/ROCK inhibition, pharmacological inhibition of SFKs by pretreatment of endothelial cells with PP2 had no effect on flow-induced stimulation of the uptake of Ab62/NC, whereas it abrogated flow-induced stimulation of Ab37/NC internalization (Fig.7).

Figure 7. Inhibition of Src family kinases specifically abolishes fluid shear stress-induced endocytosis of Ab37/NC.

A and B, pretreatment of endothelial cells with PP2 (10 μM), Src family kinases inhibitor, could not inhibit the endocytosis of Ab62/NC (200 Abs/NC (A), 50 Abs/NC (B)) under either static or flow conditions. C, PP2 pretreatment inhibited shear stress-stimulated endocytosis of Ab37/NC (200 Abs/NC). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 in comparison with static groups.

DISCUSSION

PECAM-1, a cell adhesion molecule abundantly expressed in endothelial cells, supports adhesion and trans-endothelial migration of leukocytes in inflammation sites [28–30]. Among other endothelial surface determinants, PECAM-1 is emerging as an attractive target for endothelial drug delivery [23,31,32]. Drug-loaded NC targeted to PECAM-1 bind to the endothelium and exert therapeutic effects unattainable by non-targeted drugs in animal models [32–35]. Further, endocytosis induced by multivalent Ab/NC targeted to PECAM-1 enables intra-endothelial delivery of carriers and their cargos [21,22,36]. Understanding the factors controlling endothelial delivery of Ab/NC may help to optimize drug delivery and precise addressing at the sub-cellular level, further improving therapeutic potential of this prospective drug delivery system.

Previous studies revealed that endocytosis of Ab/NC is modulated by: i) microenvironment and physiological state of endothelium; ii) specificity of binding to distinct epitopes on PECAM-1; and, iii) Ab/NC configuration (e.g., antibody surface density). Present study extends these paradigms in the context of flow, an important factor of vascular physiology that influences all aspects of Ab/NC targeting including its delivery to, binding and internalization by endothelium.

In this context, it is important to consider targeting features of the PECAM-1 antibodies employed in the study and distinguish Ab/NC internalization from binding. The data of previous studies, summarized in Supplemental table 1, indicate that Ab62 and Ab37 bind to distinct epitopes in the most distal Ig-like domain 1 (IgD1) of the extracellular portion of human PECAM-1 [37]. Noteworthy, despite the fact that Ab37 has a higher endothelial affinity than Ab62 [38], Ab62/NC bind to endothelial cells better than Ab37/NC (Fig.1A). This outcome implies that either: i) avidity of Ab62/NC is higher (e.g., due to less damaging immobilization or more optimal antibody orientation on the particle surface); or/and, ii) the accessibility of Ab62 epitope for multivalent binding of large ligands is superior to that of Ab37.

The defining specific aspects of binding and internalization is important, since Ab/NCs induce endocytosis by PECAM-1 cross-linking caused by multivalent binding. In theory, binding of more Ab/NC engaging more copies of PECAM-1 molecules per cell (attained by Ab62/NC vs Ab37/NC) may elicit stronger endocytic signal. However, data shown in Fig.2 indicate that endocytosis of Ab/NC is modulated by strength of signaling from an individual Ab/NC anchored to PECAM-1, not the total number of cell-bound Ab/NC particles or the total number of PECAM-1 copies engaged. This squares well with previous observations for NC targeted to the CAM pathway [12,18,26].

Blood flow alters the adhesive interactions between Ab/NC and endothelium [27,39]. Flow-driven rolling on the endothelial surface may assist Ab/NC in engaging PECAM-1, thereby increasing the strength of CAM-endocytic signaling. Alternatively, rotational motion due to the flow-derived torque force applied to PECAM-1-anchored Ab/NCs may further mechanically stimulate endothelial cells and enhance signaling for Ab/NC internalization.

On the other hand, flow is known to modulate many parameters of the endothelial functional status, some of which may be involved in endocytic processes directly or indirectly. In fact, shear stress governs endothelial processes including cytoskeletal remodeling, gene expression, ion transport and endocytosis [40]. It has long been recognized that internalization of extracellular fluid and macromolecules such as LDL into endothelial cells is stimulated by flow [40,41]. Stimulatory effects of flow has been observed in endothelial pinocytosis [40,42], clathrin-dependent [41,42], and CAM-dependent endocytosis [12,18]. It is conceivable that flow stimulates endocytosis via a generalized mechanism, such as enhancement of the rate of plasmalemma vesicle maturation, or dynamic changes of the cytoskeleton.

However, one could also expect that at least some components of mechanisms of flow-sensitive modulation of endocytosis are specific for distinct types of endocytic processes and, perhaps, distinct receptors and ligands. For example, flow stimulates uptake of albumin in kidney proximal tubule cells via a clathrin-dependent endocytic pathway [42]. Findings presented in our study showed for the first time that distinct mechanisms mediate flow-stimulated endothelial endocytosis of Ab/NC targeted to different epitopes of PECAM-1.

Studies in static endothelial cells showed that PECAM-1 multivalent engagement by Ab/NCs activates signaling mediated by small GTPase RhoA/ROCK pathway, leading to rapid formation of actin stress fibers, necessary for CAM-endocytosis [25,26]. In addition to “facultative” involvement in CAM-endocytosis serving “quasi-physiological” internalization of artificial objects such as Ab/NC, RhoA/ROCK is the key regulator of physiological dynamic actin rearrangements underlying endothelial responses to mechanical forces [43]. Therefore, rearrangements of actin cytoskeleton play a complex role both in Ab/NC uptake [12,18,44] and in cellular responses to shear stress [45]. On one hand, CAM-endocytosis requires recruitment of actin to the sites of Ab/NC binding and formation of stress fibers involved in vesicular uptake [46,47], on the other hand, RhoA-mediated signaling to cytoskeleton is required for endothelial functional responses to flow in the signaling chain components downstream of PECAM-1 [48]. Chronic flow exposure causes substantial commitment of actin to stable flow direction-oriented stress fibers thereby limiting actin recruitment to the endocytic pool and inhibiting CAM-endocytosis [12,18]. In contrast, transient exposure to flow stimulates CAM-endocytosis, perhaps by priming actin-rearrangement. The latter mechanism may be involved in the phenomena observed in the present study as well.

The complexity of mechanisms underlying Ab/NC endocytosis and its regulation by flow is emphasized by the fact that PECAM-1 also functions as an endothelial sensor for biomechanical stimuli including hemodynamic factors [49–51]. Thus, phosphorylation at Tyr686 residue in PECAM-1 cytosolic domain is the key event in both endothelial flow shear stress sensing [49,52] and Ab/NC internalization caused by engagement of the extracellular region under static condition [26,53].

Furthermore, in addition to RhoA/ROCK pathway, the Src family kinases (SFKs) signaling pathway is involved in both endothelial flow sensing and Ab/NC endocytosis. SFKs are signaling enzymes regulating cellular proliferation, survival, migration and metastasis [54,55]. In particular, flow causes SFK-dependent signaling in endothelial cells via PECAM-1 phosphorylation at Tyr686 [56–59]. Activation of SFKs is also involved in endocytic pathways, including caveolae- and CAM-mediated endocytosis [25,60,61]. Results shown in Fig. 6 and 7 indicate that stimulation of internalization of Ab62/NC and Ab37/NC involve alternatively RhoA/ROCK and SFK signaling pathways, respectively.

In addition to PECAM-1, specific microdomains of plasma membrane enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids, i.e., lipid rafts and caveolae, function in endothelial cells as sensing and signaling platforms for mechanotransduction [62]. These microdomains are also involved in membrane trafficking and vesicular uptake and transport [63]. Signaling and endocytic pathways sensitive to cholesterol depletion include lipid rafts, caveolae and several forms of pinocytosis [62–67]. Numerous studies showed that Ab62/NCs do not co-localize in caveolar markers during endocytosis under either static [25] or flow conditions [18]. Flow also has been shown to stimulate endothelial pinocytosis [40]. However, Ab/NC endocytosis via PECAM-1 is clearly distinct from this receptor-independent constitutive pathway for fluid-phase uptake [68]. Therefore, it is more plausible that cholesterol-rich membrane domains play indirect signaling rather than direct endocytic function in stimulation of Ab/NC internalization. Perhaps, auxiliary signaling via these domains in response to flow augments mechanosensing and endocytic functions mediated by PECAM-1. These signaling pathways are not yet fully understood but include the interplay between blood flow, cholesterol-rich plasmalemma domains, cytoskeleton rearrangements, Tyr686 phosphorylation of PECAM-1 and signaling via RhoA/ROCK and SFK (see a hypothetic schema in Fig.8).

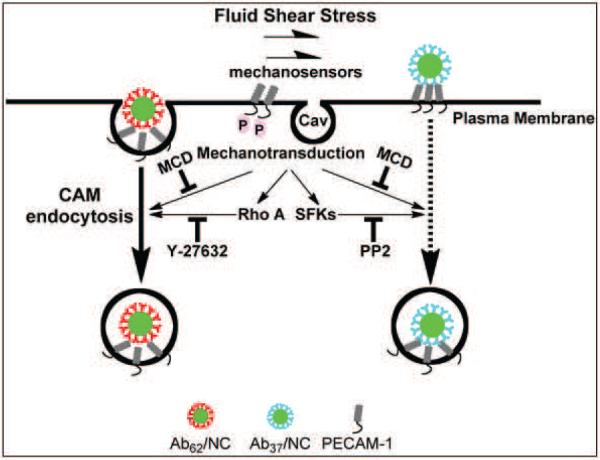

Figure 8. Fluid shear stress stimulates the endocytosis of Ab37/NC and Ab62/NC via distinct mechanisms.

Disruption of lipid rafts by methyl-β-cyclodextrin, a cholesterol chelator, abolishes acute shear stress-induced endocytosis of Ab62/NC and Ab37/NC. Blockage of RhoA/ROCK signaling pathway by Y-27632 selectively inhibits shear-stress-stimulated endocytosis of Ab62/NC. Inhibition of Src family kinases (SFKs) by PP2 specifically blocks flow-stimulated endocytosis of Ab37/NC.

Understanding the molecular mechanisms and hemodynamic control of Ab/NC internalization is important for rational design of endothelial nanomedicine targeted to specific vascular areas, particularly in those regions where the endothelium is exposed to distinct flow conditions. The context of this paper is limited principally to unidirectional flow typical of small blood vessels and the microcirculation [69], important large reservoirs of endothelial surface area for NC delivery. The ibidi system delivers levels of steady laminar shear stress that are non-pulsatile and are of low Reynolds numbers (Re) - the ratio of inertial forces to viscous forces that quantifies the relative importance of these two types of forces for given flow conditions. In contrast, Re in large arteries are much higher (Re: several hundred to > 2000) than in small arterioles and capillaries (Re: <1.0) at comparable wall shear stress values. These differences potentially have profound implications for local transport rates at the endothelial surface, an element of obvious importance to NC delivery. Exploration of NC behavior in a high Re model of arterial flow using a large volume, pulsatile fast flow system [70] will investigate complex separations of flow (eddies, vortices) typical of athero-susceptible arterial sites [71] and is beyond the scope of the present report.

It would be somewhat naive to attempt to translate our findings into a guidance which type of PECAM-1 ligands (e.g., Ab37 or Ab62) will provide optimal internalization in a vascular area of interest based on the hydrodynamic factors typical of that area. Our knowledge of mechanisms of these processes and ability to determine hydrodynamic characteristics in the patient's vessels (especially those with complex branching and meandering configuration, or/and affected by pathological process) are quite limited. However, our study indicates for the first time that, in theory, such a rational design of epitope-specific intracellular delivery governed by flow is possible. Further, it noteworthy for the drug delivery field that nearly identical carriers binding to the adjacent epitopes on the anchoring molecule may have different targeting features differently modulated by local biological factors including biomechanical conditions.

CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVES

CAM-endocytosis offers targeted delivery of NCs into endothelial cells. Our results indicate that flow modulates endothelial endocytosis of Ab/NC mediated by PECAM-1 in an epitope-specific manner, via mechanisms involving complex and differential signaling pathways (Fig. 8). The notion that flow modulates endocytosis in a PECAM-1-epitope specific manner and within a certain range of Ab/NC avidities is important in the context of selecting optimal affinity ligands and devising their configuration into drug delivery systems which need to induce intracellular transport while exposed to the circulation.

METHODS

Materials

Monoclonal antibodies to human PECAM-1 (anti-PECAM) were Ab62 and Ab37, kindly provided by Dr. Marian Nakada (Centocor) [23]. Fluorescent secondary antibodies were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) labeled polystyrene spheres (100 nm in diameter) were purchased from Polysciences (Warrington, PA). Methyl-β-cyclodextrin, Y-27632 and PP2 were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Preparation of anti-PECAM-1/NC

FITC-labeled polystyrene spheres were coated with either anti-PECAM-1 antibodies (Ab62 or Ab37) or control murine IgG via incubation at room temperature (RT) for one hour [25]. The reaction mixture was centrifuged to remove unbound materials, then re-suspended in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)-PBS and microsonicated for 20 seconds at low power. The effective immunobead diameter was determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a BI-90 Plus particle size analyzer with BI-9000AT Digital auto-correlator (Brookhaven Instruments, Brookhaven, NY). This protocol yields uniform preparations of anti-PECAM Ab/NC with particle diameters ranging from 180 to 220 nm, indicated thereafter as Ab62/NC and Ab37/NC unless specified otherwise. The saturating antibody surface coverage on the NC surface was estimated to be ~200 antibody molecules per particle [72]. To prepare Ab/NC with variable antibody surface densities (50 and 200 anti-PECAM molecules per NC), the polystyrene spheres were coated with a mix of anti-PECAM antibody and IgG at molar ratios 1:3, 1:0, respectively, keeping the total amount of IgG molecules coated per particle (including anti-PECAM Ab and IgG) constant to avoid variability due to different surface coatings [72].

Cell culture and treatments

endothelial cells used in these studies were human umbilical vein endothelial cells, purchased at passage 1 from Lonza (Walkersville, MD) and cultured for up to six passages in endothelial basal medium (EBM-2) supplemented with EGM-2 Single Quote (Lonza). Cells were starved overnight in EBM-2 containing 0.5% fetal bovine serum without supplements prior to experiments. Anti-PECAM1 Ab or IgG coated nanocarriers were then added to HBSS in the reservoir to the final carrier concentration of 2.0 × 109 carriers/ml unless specified otherwise, and were perfused for 30 minutes. Thereafter, cells were washed extensively with HBSS to remove unbound particles prior to fixation with 1% paraformaldehyde for fluorescent staining and analysis.

In the experiments to examine the effects of Methyl-β-cyclodextrin, Y-27632 and PP2 on endocytosis of Ab62/NC and Ab37/NC, endothelial cells were pre-incubated with Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (1 mM), Y-27632 (10 μM) and PP2 (10 μM) for 30 minutes. Thereafter, cells were incubated or perfused with anti-PECAM1 Ab NCs in the presence of Methyl-β-cyclodextrin, Y-27632 and PP2 for 30 minutes.

The human mesothelioma REN cells stably expressing human wild-type PECAM-1 or cytoplasmic domain deleted mutant ΔPECAM-1 used in this study have been previously described [26]. REN cells were cultured in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and Geneticin (G418) as a selection agent.

In vitro laminar shear stress system

A six-channel μ-slide flow chamber (Ibidi, Germany) was used to subject endothelial monolayers to defined laminar shear stress. The chamber was connected to a recirculating flow circuit composed of a variable-speed peristaltic pump (Rainin RP-1, Columbus,OH), a reservoir with culture medium, and inlet and outlet silicone rubber tubing. The flow rate was calibrated by collecting the volume of medium discharged per minute. The wall shear stress generated by fully-developed fluid flow through the channel was calculated using τ = 6μQ/h3w, where μ is the fluid viscosity (μ = 0.70 cP for HBSS at 37 °C), Q is the mean velocity of the flow through the channel, and H and W are the channel height (0.4 mm) and width (3.8 mm), respectively. Shear stresses were in the range 0 – 8 dynes/cm2. The temperature was maintained at 37 °C, and pH and gases were maintained in a 95% air/ 5% CO2 incubation chamber.

Microscopy and quantification of cell-bound and internalized Ab/NC

Endothelial monolayers or REN cells were washed with Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS) to remove unbound NC following endothelial uptake of Ab/NC. Cells were then fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes. To distinguish between surface-bound or internalized immunobeads, non-permeabilized fixed cells were counterstained for 30 minutes at RT with Alexa-Fluor-594-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG to produce double-labeled, yellow particles. The cells were washed five times with HBSS containing 0.05% Tween-20, mounted with ProLong Antifade Kit (Molecular probes, Eugene OR) and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy.

Endothelial cells grown in the flow chamber were exposed to flow (4 dyne/cm2) for 30 minutes. Cells were fixed, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min, and stained for F-actin (stress fibers) with Alexa-Fluor-594-phalloidin (Molecular probes, Eugene, OR).

Fluorescence microscopy was performed with an Olympus IX70 inverted fluorescence microscope, 40× PlanApo objectives and filters optimized for green fluorescence (excitation BP460-490 nm, dichroic DM570 nm, emission BA515-550 nm) and red fluorescence (excitation BP530-550 nm, dichroic DM570 nm, emission BA590-800+). Separate images for each fluorescence channel were acquired using a Hamamatsu Orca-1 CCD camera. The images in green and red channel were merged and analyzed with ImagePro 3.0 imaging software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). Green and red fluorescence images were separately obtained by means of gain and exposure times that were optimized to produce 8-bit images with average background intensity values of approximately 20 bits per pixel and average maximum intensity values of approximately 250 bits per pixel (below saturation). Once the settings were established, they were used for all images obtained for a given sample. For particle quantification, double-labeled particles showing yellow color were identified as surface bound immunobeads by generating a new RBG image merging the green and red channels, and were scored using ImageJ particle analyze plugin with the constraint that only regions with 4 or more continuous pixels and with an intensity threshold of 128 were counted. The green fluorescence image was then scored in a compatible manner to give the total number of immunobeads in the field. Endocytosis was calculated as the percentage of internalized immunobeads with respect to the total number of cell-associated immunobeads. The data are shown as means from ≥ 6 images ± S.E. Statistical significance between groups was determined by Student's t test and was accepted as significant at p < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This study is supported by R01 HL073940 and HL087036 (V.R.M), U01 EB016027 (D.M.E.), P01 HL062250 and T32 HL007954 (P.F.D.), R01 HL098416 and CBET 1402756 (S.M.), and AHA SDG20140036 (J.H.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- [1].Champion JA, Mitragotri S. Role of target geometry in phagocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:4930–4934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600997103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gratton SE, Ropp PA, Pohlhaus PD, Luft JC, Madden VJ, Napier ME, DeSimone JM. The effect of particle design on cellular internalization pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:11613–11618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801763105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Reilly MJ, Larsen JD, Sullivan MO. Polyplexes Traffic through Caveolae to the Golgi and Endoplasmic Reticulum en Route to the Nucleus. Mol. Pharm. 2012 doi: 10.1021/mp200583d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bonner DK, Leung C, Chen-Liang J, Chingozha L, Langer R, Hammond PT. Intracellular trafficking of polyamidoamine-poly(ethylene glycol) block copolymers in DNA delivery. Bioconjug. Chem. 2011;22:1519–1525. doi: 10.1021/bc200059v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Evans CW, Fitzgerald M, Clemons TD, House MJ, Padman BS, Shaw JA, Saunders M, Harvey AR, Zdyrko B, Luzinov I, Silva GA, Dunlop SA, Iyer KS. Multimodal analysis of PEI-mediated endocytosis of nanoparticles in neural cells. ACS Nano. 2011;5:8640–8648. doi: 10.1021/nn2022149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Holt BD, Dahl KN, Islam MF. Cells Take up and Recover from Protein-Stabilized Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes with Two Distinct Rates. ACS Nano. 2012;6:3481–3490. doi: 10.1021/nn300504x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Oh E, Delehanty JB, Sapsford KE, Susumu K, Goswami R, Blanco-Canosa JB, Dawson PE, Granek J, Shoff M, Zhang Q, Goering PL, Huston A, Medintz IL. Cellular uptake and fate of PEGylated gold nanoparticles is dependent on both cell-penetration peptides and particle size. ACS Nano. 2011;5:6434–6448. doi: 10.1021/nn201624c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Skotland T, Iversen TG, Sandvig K. Comment on “short ligands affect modes of QD uptake and elimination in human cells”. ACS Nano. 2011;5:7690. doi: 10.1021/nn2021953. author reply 7691–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Davies PF. Flow-mediated endothelial mechanotransduction. Physiol. Rev. 1995;75:519–560. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.3.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Charoenphol P, Huang RB, Eniola-Adefeso O. Potential role of size and hemodynamics in the efficacy of vascular-targeted spherical drug carriers. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1392–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Calderon AJ, Muzykantov V, Muro S, Eckmann DM. Flow dynamics, binding and detachment of spherical carriers targeted to ICAM-1 on endothelial cells. Biorheology. 2009;46:323–341. doi: 10.3233/BIR-2009-0544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bhowmick T, Berk E, Cui X, Muzykantov VR, Muro S. Effect of flow on endothelial endocytosis of nanocarriers targeted to ICAM-1. J. Control. Release. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lin A, Sabnis A, Kona S, Nattama S, Patel H, Dong JF, Nguyen KT. Shear-regulated uptake of nanoparticles by endothelial cells and development of endothelial-targeting nanoparticles. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2010;93:833–842. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Igarashi R, Takenaga M, Takeuchi J, Kitagawa A, Matsumoto K, Mizushima Y. Marked hypotensive and blood flow-increasing effects of a new lipo-PGE(1) (lipo-AS013) due to vascular wall targeting. J. Control. Release. 2001;71:157–164. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00373-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Charoenphol P, Onyskiw PJ, Carrasco-Teja M, Eniola-Adefeso O. Particle-cell dynamics in human blood flow: implications for vascular-targeted drug delivery. J. Biomech. 2012;45:2822–2828. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Samuel SP, Jain N, O'Dowd F, Paul T, Kashanin D, Gerard VA, Gun'ko YK, Prina-Mello A, Volkov Y. Multifactorial determinants that govern nanoparticle uptake by human endothelial cells under flow. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2012;7:2943–2956. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S30624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Nguyen KT, Shukla KP, Moctezuma M, Braden AR, Zhou J, Hu Z, Tang L. Studies of the cellular uptake of hydrogel nanospheres and microspheres by phagocytes, vascular endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2009;88:1022–1030. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Han J, Zern BJ, Shuvaev VV, Davies PF, Muro S, Muzykantov V. Acute and chronic shear stress differently regulate endothelial internalization of nanocarriers targeted to platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1. ACS Nano. 2012;6:8824–8836. doi: 10.1021/nn302687n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chorny M, Hood E, Levy RJ, Muzykantov VR. Endothelial delivery of antioxidant enzymes loaded into non-polymeric magnetic nanoparticles. J. Control. Release. 2010;146:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ding BS, Hong N, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Gottstein C, Albelda SM, Cines DB, Fisher AB, Muzykantov VR. Anchoring fusion thrombomodulin to the endothelial lumen protects against injury-induced lung thrombosis and inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009;180:247–256. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200809-1433OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Shuvaev VV, Han J, Yu KJ, Huang S, Hawkins BJ, Madesh M, Nakada M, Muzykantov VR. PECAM-targeted delivery of SOD inhibits endothelial inflammatory response. FASEB J. 2011;25:348–357. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-169789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Han J, Shuvaev VV, Muzykantov VR. Catalase and superoxide dismutase conjugated with platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule antibody distinctly alleviate abnormal endothelial permeability caused by exogenous reactive oxygen species and vascular endothelial growth factor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011;338:82–91. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.180620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Muzykantov VR, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Balyasnikova I, Harshaw DW, Schultz L, Fisher AB, Albelda SM. Streptavidin facilitates internalization and pulmonary targeting of an anti-endothelial cell antibody (platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1): a strategy for vascular immunotargeting of drugs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:2379–2384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wiewrodt R, Thomas AP, Cipelletti L, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Weitz DA, Feinstein SI, Schaffer D, Albelda SM, Koval M, Muzykantov VR. Size-dependent intracellular immunotargeting of therapeutic cargoes into endothelial cells. Blood. 2002;99:912–922. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Muro S, Wiewrodt R, Thomas A, Koniaris L, Albelda SM, Muzykantov VR, Koval M. A novel endocytic pathway induced by clustering endothelial ICAM-1 or PECAM-1. J. Cell. Sci. 2003;116:1599–1609. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Garnacho C, Shuvaev V, Thomas A, McKenna L, Sun J, Koval M, Albelda S, Muzykantov V, Muro S. RhoA activation and actin reorganization involved in endothelial CAM-mediated endocytosis of anti-PECAM carriers: critical role for tyrosine 686 in the cytoplasmic tail of PECAM-1. Blood. 2008;111:3024–3033. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-098657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Liu J, Weller GE, Zern B, Ayyaswamy PS, Eckmann DM, Muzykantov VR, Radhakrishnan R. Computational model for nanocarrier binding to endothelium validated using in vivo, in vitro, and atomic force microscopy experiments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:16530–16535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006611107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ilan N, Madri JA. PECAM-1: old friend, new partners. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003;15:515–524. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Woodfin A, Voisin MB, Nourshargh S. PECAM-1: a multi-functional molecule in inflammation and vascular biology. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007;27:2514–2523. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.151456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Privratsky JR, Newman DK, Newman PJ. PECAM-1: conflicts of interest in inflammation. Life Sci. 2010;87:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Muzykantov VR. Delivery of antioxidant enzyme proteins to the lung. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2001;3:39–62. doi: 10.1089/152308601750100489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Scherpereel A, Rome JJ, Wiewrodt R, Watkins SC, Harshaw DW, Alder S, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Haut E, Murciano JC, Nakada M, Albelda SM, Muzykantov VR. Platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1-directed immunotargeting to cardiopulmonary vasculature. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002;300:777–786. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.3.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ding BS, Hong N, Murciano JC, Ganguly K, Gottstein C, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Albelda SM, Fisher AB, Cines DB, Muzykantov VR. Prophylactic thrombolysis by thrombin-activated latent prourokinase targeted to PECAM-1 in the pulmonary vasculature. Blood. 2008;111:1999–2006. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-103002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Dziubla TD, Shuvaev VV, Hong NK, Hawkins BJ, Madesh M, Takano H, Simone E, Nakada MT, Fisher A, Albelda SM, Muzykantov VR. Endothelial targeting of semi-permeable polymer nanocarriers for enzyme therapies. Biomaterials. 2008;29:215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hsu J, Northrup L, Bhowmick T, Muro S. Enhanced delivery of alpha-glucosidase for Pompe disease by ICAM-1-targeted nanocarriers: comparative performance of a strategy for three distinct lysosomal storage disorders. Nanomedicine. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Muro S. New biotechnological and nanomedicine strategies for treatment of lysosomal storage disorders. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2010;2:189–204. doi: 10.1002/wnan.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Nakada MT, Amin K, Christofidou-Solomidou M, O'Brien CD, Sun J, Gurubhagavatula I, Heavner GA, Taylor AH, Paddock C, Sun QH, Zehnder JL, Newman PJ, Albelda SM, DeLisser HM. Antibodies against the first Ig-like domain of human platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) that inhibit PECAM-1-dependent homophilic adhesion block in vivo neutrophil recruitment. J. Immunol. 2000;164:452–462. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chacko AM, Nayak M, Greineder CF, Delisser HM, Muzykantov VR. Collaborative enhancement of antibody binding to distinct PECAM-1 epitopes modulates endothelial targeting. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ayyaswamy PS, Muzykantov V, Eckmann DM, Radhakrishnan R. Nanocarrier Hydrodynamics and Binding in Targeted Drug Delivery: Challenges in Numerical Modeling and Experimental Validation. J. Nanotechnol Eng. Med. 2013;4:101011–1010115. doi: 10.1115/1.4024004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Davies PF, Dewey CF, Jr, Bussolari SR, Gordon EJ, Gimbrone MA., Jr Influence of hemodynamic forces on vascular endothelial function. In vitro studies of shear stress and pinocytosis in bovine aortic cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1984;73:1121–1129. doi: 10.1172/JCI111298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sprague EA, Steinbach BL, Nerem RM, Schwartz CJ. Influence of a laminar steady-state fluid-imposed wall shear stress on the binding, internalization, and degradation of low-density lipoproteins by cultured arterial endothelium. Circulation. 1987;76:648–656. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.3.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Raghavan V, Rbaibi Y, Pastor-Soler NM, Carattino MD, Weisz OA. Shear stress-dependent regulation of apical endocytosis in renal proximal tubule cells mediated by primary cilia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:8506–8511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402195111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Collins C, Tzima E. RhoA goes GLOBAL. Small GTPases. 2013;4:123–126. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.24190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Garnacho C, Dhami R, Simone E, Dziubla T, Leferovich J, Schuchman EH, Muzykantov V, Muro S. Delivery of acid sphingomyelinase in normal and niemann-pick disease mice using intercellular adhesion molecule-1-targeted polymer nanocarriers. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;325:400–408. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.133298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Marjoram RJ, Lessey EC, Burridge K. Regulation of RhoA activity by adhesion molecules and mechanotransduction. Curr. Mol. Med. 2014;14:199–208. doi: 10.2174/1566524014666140128104541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Serrano D, Bhowmick T, Chadha R, Garnacho C, Muro S. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 engagement modulates sphingomyelinase and ceramide, supporting uptake of drug carriers by the vascular endothelium. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012;32:1178–1185. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.244186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Muro S, Mateescu M, Gajewski C, Robinson M, Muzykantov VR, Koval M. Control of intracellular trafficking of ICAM-1-targeted nanocarriers by endothelial Na+/H+ exchanger proteins. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2006;290:L809–17. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00311.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Collins C, Guilluy C, Welch C, O'Brien ET, Hahn K, Superfine R, Burridge K, Tzima E. Localized tensional forces on PECAM-1 elicit a global mechanotransduction response via the integrin-RhoA pathway. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:2087–2094. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Fujiwara K. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 and mechanotransduction in vascular endothelial cells. J. Intern. Med. 2006;259:373–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kaufman DA, Albelda SM, Sun J, Davies PF. Role of lateral cell-cell border location and extracellular/transmembrane domains in PECAM/CD31 mechanosensation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;320:1076–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Masuda M, Kogata N, Mochizuki N. Crucial roles of PECAM-1 in shear stress sensing of vascular endothelial cells. Nippon Yakurigaku Zasshi. 2004;124:311–318. doi: 10.1254/fpj.124.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Newman PJ, Newman DK. Signal transduction pathways mediated by PECAM-1: new roles for an old molecule in platelet and vascular cell biology. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003;23:953–964. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000071347.69358.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Garnacho C, Albelda SM, Muzykantov VR, Muro S. Differential intra-endothelial delivery of polymer nanocarriers targeted to distinct PECAM-1 epitopes. J. Control. Release. 2008;130:226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Thomas SM, Brugge JS. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1997;13:513–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Yeatman TJ. A renaissance for SRC. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4:470–480. doi: 10.1038/nrc1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Chiu YJ, McBeath E, Fujiwara K. Mechanotransduction in an extracted cell model: Fyn drives stretch- and flow-elicited PECAM-1 phosphorylation. J. Cell Biol. 2008;182:753–763. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Lu TT, Barreuther M, Davis S, Madri JA. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 is phosphorylatable by c-Src, binds Src-Src homology 2 domain, and exhibits immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif-like properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:14442–14446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Jackson DE, Kupcho KR, Newman PJ. Characterization of phosphotyrosine binding motifs in the cytoplasmic domain of platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) that are required for the cellular association and activation of the protein-tyrosine phosphatase, SHP-2. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:24868–24875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Cao MY, Huber M, Beauchemin N, Famiglietti J, Albelda SM, Veillette A. Regulation of mouse PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation by the Src and Csk families of protein-tyrosine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:15765–15772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Shajahan AN, Timblin BK, Sandoval R, Tiruppathi C, Malik AB, Minshall RD. Role of Src-induced dynamin-2 phosphorylation in caveolae-mediated endocytosis in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:20392–20400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308710200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Zloza A, Kim DW, Broucek J, Schenkel JM, Kaufman HL. High-dose IL-2 induces rapid albumin uptake by endothelial cells through Src-dependent caveolae-mediated endocytosis. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2014;34:915–919. doi: 10.1089/jir.2013.0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Xing Y, Gu Y, Xu LC, Siedlecki CA, Donahue HJ, You J. Effects of membrane cholesterol depletion and GPI-anchored protein reduction on osteoblastic mechanotransduction. J. Cell. Physiol. 2011;226:2350–2359. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Lajoie P, Nabi IR. Lipid rafts, caveolae, and their endocytosis. Int. Rev. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2010;282:135–163. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(10)82003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Ferraro JT, Daneshmand M, Bizios R, Rizzo V. Depletion of plasma membrane cholesterol dampens hydrostatic pressure and shear stress-induced mechanotransduction pathways in osteoblast cultures. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 2004;286:C831–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00224.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Nabi IR, Le PU. Caveolae/raft-dependent endocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 2003;161:673–677. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Laughlin RC, McGugan GC, Powell RR, Welter BH, Temesvari LA. Involvement of raft-like plasma membrane domains of Entamoeba histolytica in pinocytosis and adhesion. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:5349–5357. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5349-5357.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Grimmer S, van Deurs B, Sandvig K. Membrane ruffling and macropinocytosis in A431 cells require cholesterol. J. Cell. Sci. 2002;115:2953–2962. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.14.2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Muro S, Cui X, Gajewski C, Murciano JC, Muzykantov VR, Koval M. Slow intracellular trafficking of catalase nanoparticles targeted to ICAM-1 protects endothelial cells from oxidative stress. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 2003;285:C1339–47. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00099.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Koutsiaris AG, Tachmitzi SV, Batis N, Kotoula MG, Karabatsas CH, Tsironi E, Chatzoulis DZ. Volume flow and wall shear stress quantification in the human conjunctival capillaries and post-capillary venules in vivo. Biorheology. 2007;44:375–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Jimenez JM, Prasad V, Yu MD, Kampmeyer CP, Kaakour AH, Wang PJ, Maloney SF, Wright N, Johnston I, Jiang YZ, Davies PF. Macro- and microscale variables regulate stent haemodynamics, fibrin deposition and thrombomodulin expression. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2014;11:20131079. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2013.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Davies PF. Hemodynamic shear stress and the endothelium in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 2009;6:16–26. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Muro S, Dziubla T, Qiu W, Leferovich J, Cui X, Berk E, Muzykantov VR. Endothelial targeting of high-affinity multivalent polymer nanocarriers directed to intercellular adhesion molecule 1. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;317:1161–1169. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.098970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.